Mg-Air Battery with High Coulombic Efficiency and Discharge Current by Electrode and Electrolyte Modification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

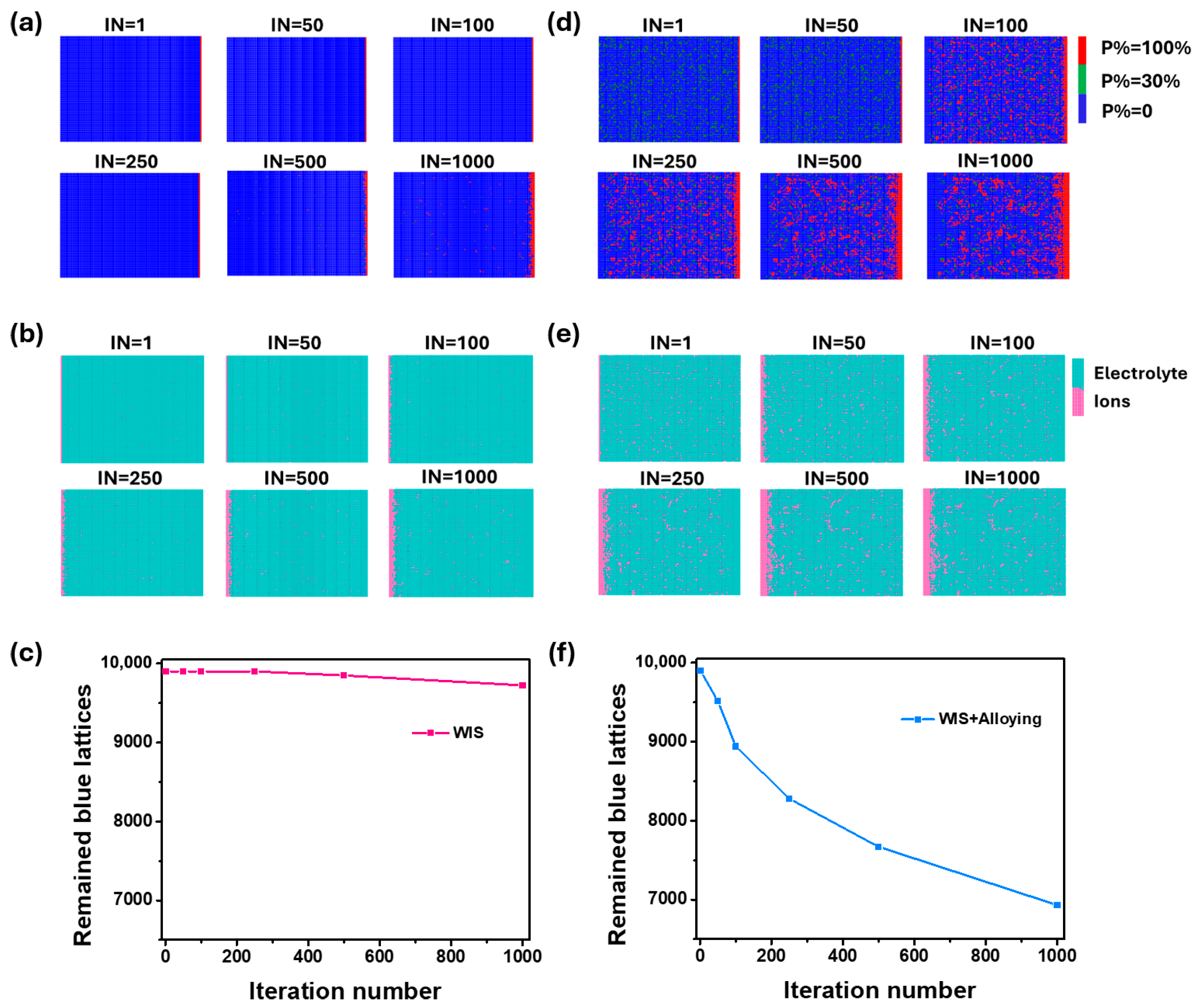

2.1. Electrode Corrosion Simulation

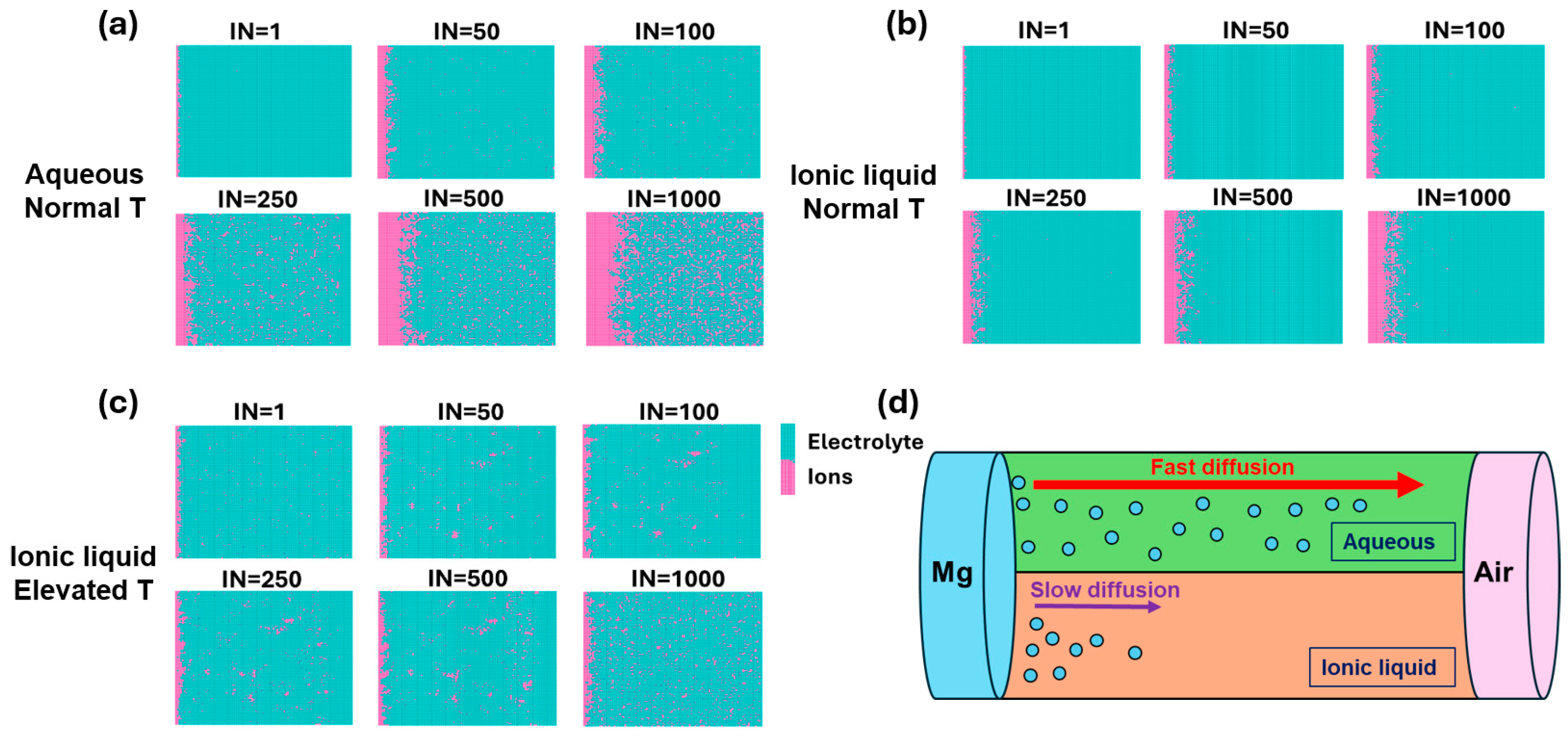

2.2. Ion Migration Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, P.; Qiu, W.; Chen, W.; Chen, J. Tailoring the electrochemical behavior and discharge performance of Mg–Al–Ca–Mn anodes for Mg-air batteries by different extrusion ratios. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 3494–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Song, G.L.; Zheng, D.; Cao, F. A corrosion resistant die-cast Mg-9Al-1Zn anode with superior discharge performance for Mg-air battery. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Niu, J.; Liu, Y.; Bridges, D.; Liu, X.; Pooran, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, A. Recent progress of metal-air batteries—A mini review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.G.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, Z. Recent progress in rechargeable alkali metal–air batteries. Green Energy Environ. 2016, 1, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.F.; Xu, Q. Materials Design for Rechargeable Metal-Air Batteries. Matter 2019, 1, 565–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Sayed, E.T.; Wilberforce, T.; Jamal, A.; Alami, A.H.; Elsaid, K.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Shah, S.K.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Metal-air batteries—A review. Energies 2021, 14, 7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Chen, X.; Wei, S.; Malmström, J.; Vella, J.; Gao, W. Microstructure and battery performance of Mg-Zn-Sn alloys as anodes for magnesium-air battery. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2021, 9, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, F.W.; McCloskey, B.D.; Luntz, A.C. Mg Anode Corrosion in Aqueous Electrolytes and Implications for Mg-Air Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A958–A963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, G.; Li, H.; Tang, S.; Xiu, D.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Cheng, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, J. The Discharge Performance of Mg-3In-xCa Alloy Anodes for Mg–Air Batteries. Coatings 2022, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, F.E.; Cheng, W.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Cui, Z.Q.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.X.; Wang, L.F.; Li, H.; Hou, H. Role of micro-Ca/In alloying in tailoring the microstructural characteristics and discharge performance of dilute Mg-Bi-Sn-based alloys as anodes for Mg-air batteries. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2024, 12, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, J. An overview of non-noble metal electrocatalysts and their associated air cathodes for Mg-air batteries. Mater. Rep. Energy 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Le, Q.; Zou, Q. Discharge performance of Mg-Al-Cd anode for Mg-air Battery. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 046521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; NuLi, Y. Challenges and prospects of Mg-air batteries: A review. Energy Mater. 2022, 2, 200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Wei, S.; Chen, X.; Gao, W. Magnesium alloys as anodes for neutral aqueous magnesium-air batteries. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2021, 9, 1861–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, K.W.; Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, X.; Leung, D.Y.C. Reversibility of a High-Voltage, Cl—Regulated, Aqueous Mg Metal Battery Enabled by a Water-in-Salt Electrolyte. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Huang, M.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.X. Metal–air batteries: A review on current status and future applications. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2023, 33, 237362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, B.; Teng, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L.; Ren, P.; Zhang, J.; Feng, M. Advanced noble-metal-free bifunctional electrocatalysts for metal-air batteries. J. Mater. 2022, 8, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, H.; Wu, T.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Shi, Z. Tailoring the microstructure of Mg-Al-Sn-RE alloy via friction stir processing and the impact on its electrochemical discharge behaviour as the anode for Mg-air battery. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2024, 12, 1554–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, B.; Huang, L.; Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Shi, Z.; Wang, N. Fe/Cu diatomic sites dispersed on nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon for the boosted oxygen reduction reaction in Mg-air and Zn-air batteries. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 358, 124450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, P.; Jia, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G. Organic/inorganic double solutions for magnesium-air batteries. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 7502–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.S.; Sun, Y.; Gebert, F.; Chou, S.L. Current Progress on Rechargeable Magnesium–Air Battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.E.; Luo, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L. Effect of sodium-zinc EDTA and sodium gluconate as electrolyte additives on corrosion and discharge behavior of Mg as anode for air battery. Mater. Corros. 2022, 73, 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, C.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; Macfarlane, D.R.; Forsyth, M.; Wallace, G.G. Biocompatible ionic liquid-biopolymer electrolyte-enabled thin and compact magnesium-Air batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21110–21117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Y.T.; Schnaidt, J.; Brimaud, S.; Behm, R.J. Oxygen reduction and evolution in an ionic liquid ([BMP][TFSA]) based electrolyte: A model study of the cathode reactions in Mg-air batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 333, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, N.; Fan, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. Enhancement of the discharge behavior for Mg-air battery by adjusting the chelate ability of ionic liquid electrolyte additives. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskew, M.J.; Nikman, S.; O’Sullivan, C.E.; Galeb, H.A.; Halcovitch, N.R.; Hardy, J.G.; Murphy, S.T. Mg/Zn metal—Air primary batteries using silk fibroin—Ionic liquid polymer electrolytes. Nano Sel. 2023, 4, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, J.; Lin, Y.; Ren, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, H.; Pan, L.; Lin, Q.; Liu, H.; et al. Simultaneous optimization of solvation structure and water-resistant capability of MgCl2-based electrolyte using an additive combination of organic and inorganic lithium salts. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 51, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombona-Pascual, A.; Patil, N.; García-Quismondo, E.; Goujon, N.; Mecerreyes, D.; Marcilla, R.; Palma, J.; Lado, J.J. A high performance all-polymer symmetric faradaic deionization cell. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 142001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, K.W.; Pan, W.; Yi, X.; Luo, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mao, J.; Chen, Y.; Xuan, J.; et al. Next-generation magnesium-ion batteries: The quasi-solid-state approach to multivalent metal ion storage. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chen, X.Q.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Dong, J.; Ke, W. First-principles modeling of anisotropic anodic dissolution of metals and alloys in corrosive environments. Acta Mater. 2017, 130, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bao, J.; Sha, J.; Zhang, Z. Modulation of the Discharge and Corrosion Properties of Aqueous Mg-Air Batteries by Alloying from First-Principles Theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 10062–10068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhauriyal, P.; Rawat, K.S.; Bhattacharyya, G.; Garg, P.; Pathak, B. First-Principles Study of Magnesium Peroxide Nucleation for Mg-Air Battery. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 3198–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Snihirova, D.; Wang, L.; Deng, M.; Wang, C.; Lamaka, S.V.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Höche, D. Mathematical modeling of salicylate effects on high-purity Mg anode for aqueous primary Mg-Air batteries. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2025, 13, 1506–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Snihirova, D.; Deng, M.; Wang, L.; Vaghefinazari, B.; Wang, C.; Lamaka, S.V.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Höche, D. A mathematical model describing the surface evolution of Mg anode during discharge of aqueous Mg-air battery. J. Power Sources 2022, 542, 231745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Z.; Chen, X.; Atrens, A. Anodic hydrogen evolution on Mg. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2021, 9, 2049–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Medhekar, N.V.; Frankel, G.S.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion mechanism and hydrogen evolution on Mg. Curr. Opin. Solid. State Mater. Sci. 2015, 19, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Quan, B.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Zeng, X. Solid solution strengthening mechanism in high pressure die casting Al–Ce–Mg alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 812, 141109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, F.; Wang, Q.; Tai, L.; Xu, G. Improved Perovskite Structural Stability by Halogen Bond from Excessive Lead Iodide via Numerical Simulation. Crystals 2022, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.T.; Xu, A.F.; Zhang, W.; Xu, G. The influence of compression on the lattice stability of α-FAPbI3 revealed by numerical simulation. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 16130–16137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.T.; Jin, X.; Tan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Abbas, A.; Lyu, B.; Xu, F. Hindered Phase Transition Kinetics of α-CsPbI3 by External Tension. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2300523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Latham, J.A.; Macfarlane, D.R.; Howlett, P.C.; Forsyth, M. A review of ionic liquid surface film formation on Mg and its alloys for improved corrosion performance. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 110, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J. Experimental and theoretical studies on corrosion inhibition behavior of three imidazolium-based ionic liquids for magnesium alloys in sodium chloride solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 345, 116998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Kousis, C.; McMurray, N.; Keil, P. A mechanistic investigation of corrosion-driven organic coating failure on magnesium and its alloys. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2019, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Q.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.T.; Zanna, S.; Seyeux, A.; Marcus, P.; Światowska, J. Probing Mg anode interfacial and corrosion properties using an organic/inorganic hybrid electrolyte. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 614, 156070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; An, Y.; Yang, W.; Yang, W.; Ji, Y.; Xu, F. Mg-Air Battery with High Coulombic Efficiency and Discharge Current by Electrode and Electrolyte Modification. Coatings 2025, 15, 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121493

Wang T, An Y, Yang W, Yang W, Ji Y, Xu F. Mg-Air Battery with High Coulombic Efficiency and Discharge Current by Electrode and Electrolyte Modification. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121493

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Taoran, Yanyan An, Wenjuan Yang, Wenchang Yang, Yongqiang Ji, and Fan Xu. 2025. "Mg-Air Battery with High Coulombic Efficiency and Discharge Current by Electrode and Electrolyte Modification" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121493

APA StyleWang, T., An, Y., Yang, W., Yang, W., Ji, Y., & Xu, F. (2025). Mg-Air Battery with High Coulombic Efficiency and Discharge Current by Electrode and Electrolyte Modification. Coatings, 15(12), 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121493