Effect of Anodizing and Welding Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded A356 Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

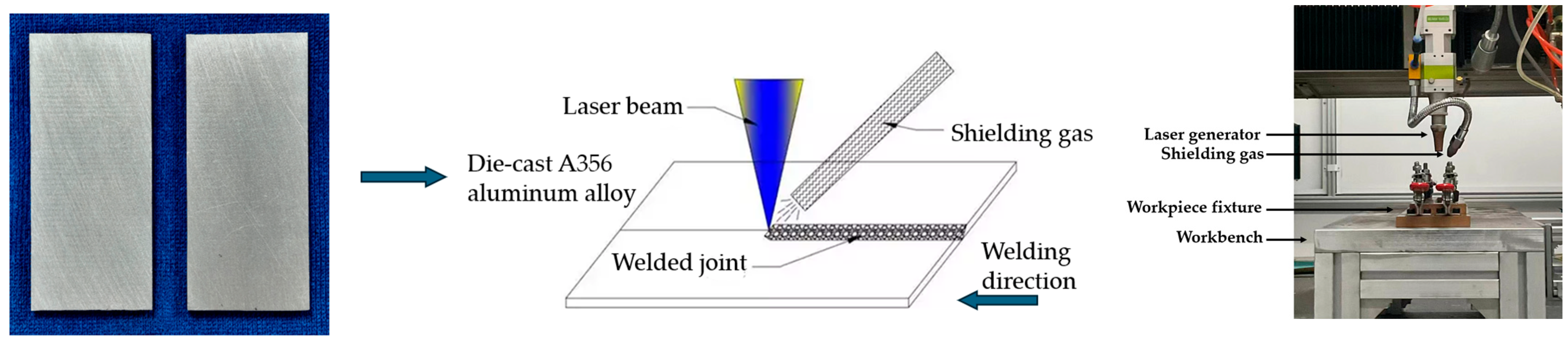

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Base Materials

2.2. Anodic Oxidation of Aluminum Alloy Surfaces

2.3. Laser Beam Welding

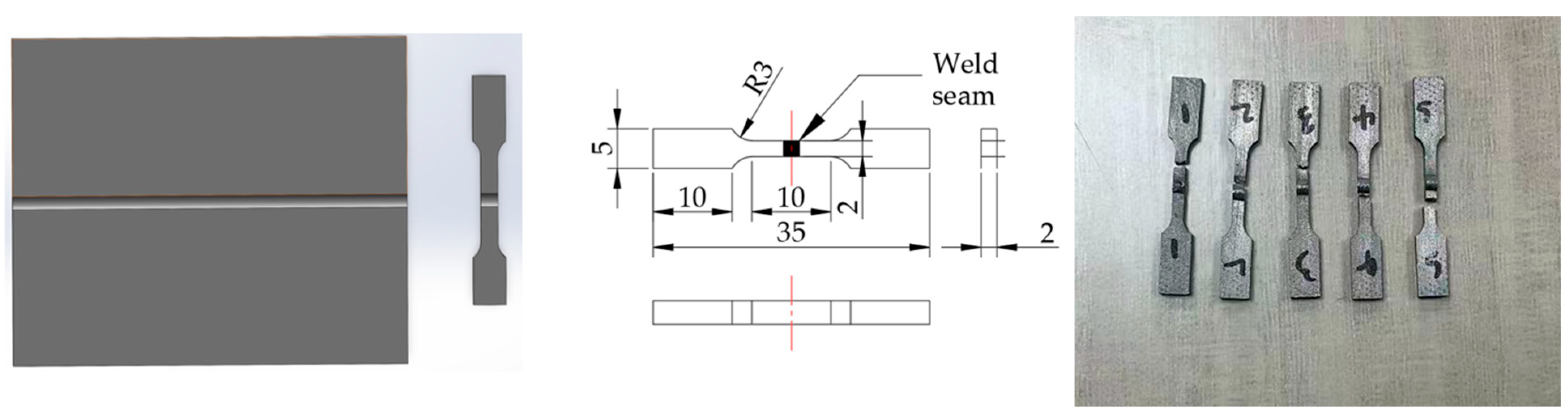

2.4. Characterization and Properties Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Welding Morphology and Microstructure

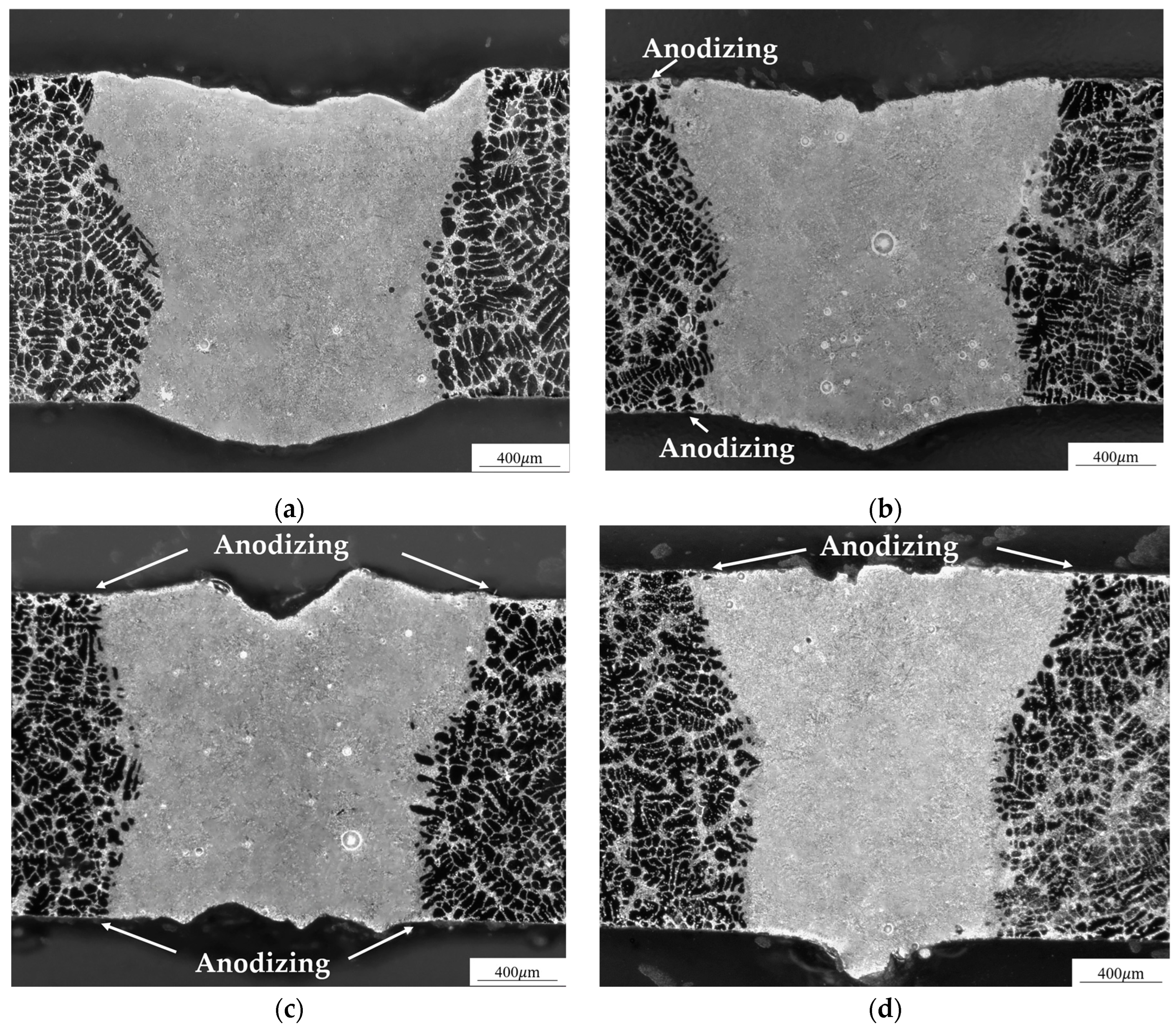

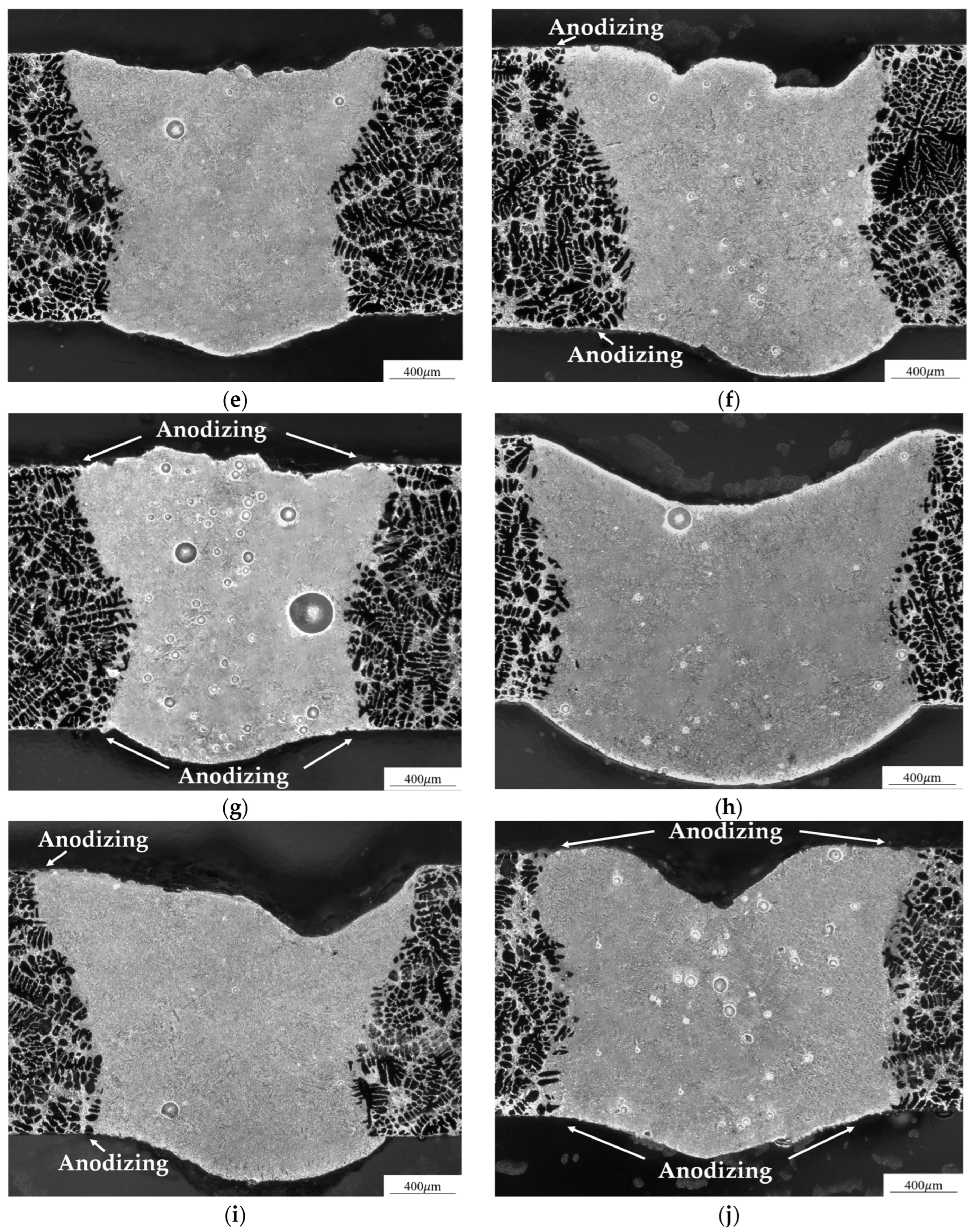

3.1.1. Cross-Section Macrostructure and Porosity

3.1.2. Element Distribution and Phase Composition in the Weld Seam

3.1.3. Microstructure of Welded Joints

3.2. Microhardness of Welded Joints

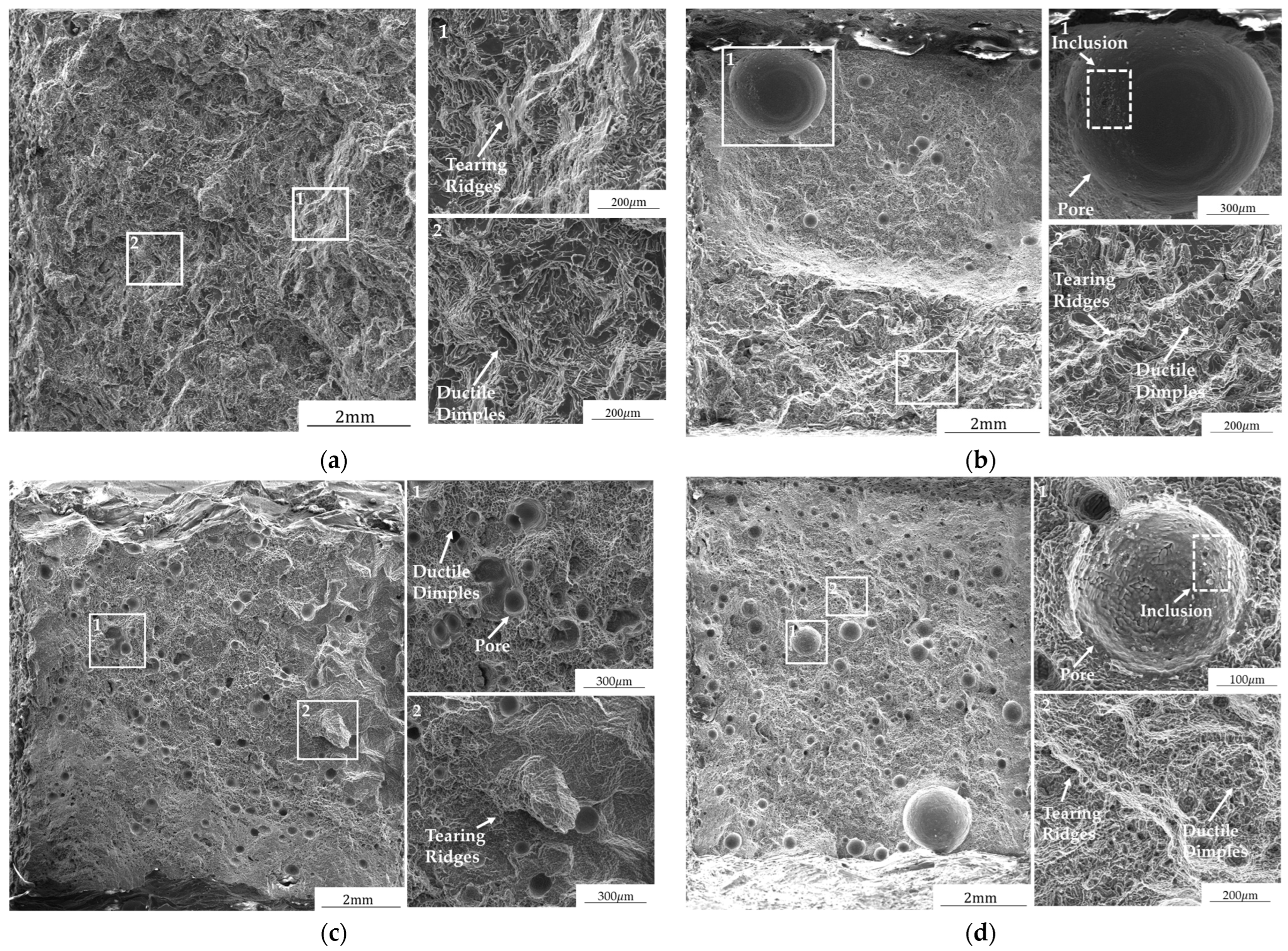

3.3. Tensile Property

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Anodizing fundamentally alters weld formation, reducing the FZ size by approximately 5%–15% and significantly increasing porosity from 3.09% (NAF) to 9.25% (DSAF), owing to its thermal-barrier effect, energy consumption during film decomposition, and hydrogen generation.

- (2)

- Welding parameters regulate heat input and melt-pool flow, with lower welding speeds (3 m/min) leading to a 15% increase in fusion zone (FZ) area and a 2%–5% increase in porosity. The larger positive defocusing amount further amplifies these effects, whereas optimized conditions (welding speed of 4 m/mins and defocusing amount of 0 mm) enhance gas evacuation and effectively suppress pore formation, reduce porosity by 1%–2%, with values of 4.01% for NAF, 4.94% for SSAF, and 4.62% for DSAF.

- (3)

- Anodizing fundamentally governs elemental redistribution and oxygen incorporation in the weld seam. Anodized films increase oxygen content by 10%–15%, with DSAF samples exhibiting the highest oxygen content at 1.31 wt%, compared to 0.78 wt% in NAF samples, as shown in Figure 11. While welding parameters exert limited influence on major alloying elements but strongly regulate oxygen behavior through their effects on melt-pool dynamics and atmospheric interaction.

- (4)

- Anodizing reduces HAZ hardness by amplifying thermal softening and Mg burnout, while welding parameters primarily modulate FZ hardness through energy density and melt-pool agitation, with the highest hardness achieved at the welding speed of 4 m/mins and defocusing amount of 0 mm, with a maximum average hardness value of 95.66 ± 5.32 HV.

- (5)

- Anodizing enhances FZ yield strength (10%–15% higher than NAF) through retained oxide particles but reduces ductility via increased porosity. Optimized welding parameters (welding speed of 4 m/mins and defocusing amount of 0 mm) enhance strength and delay fracture toward the BM, whereas lower speeds or positive defocus increase porosity, reduce ductility, and promote FZ/HAZ failure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, D.Y.; Li, S.; Ma, S.D.; Wang, L.S.; Kang, J.; Dong, H.C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.D.; Su, R. Multi-scale investigation of A356 alloy with trace Ce addition processed by laser surface remelting. Mater. Charact. 2022, 188, 111895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.N.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.F.; Zhang, G.C. Effect of preheat & post-weld heat treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 6061-T6 aluminum alloy welded sheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 841, 143081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, G.R.; Du, W.B.; Li, Y.; Fan, C.L.; Zhang, H.J. Influence of heat input on the appearance, microstructure and microhardness of pulsed gas metal arc welded Al alloy weldment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Meng, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.K.; Wang, Q.; Shan, J.G.; Song, J.L.; Wang, G.Q.; Wu, A.P. Improvement on the tensile properties of 2219-T8 aluminum alloy TIG welding joint with weld geometry optimization. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 67, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Chen, K.; Jiang, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Su, X.; Wang, Z.B.; He, P.; Peng, G.C.; Chen, Y.B. Complete-joint-penetration vacuum laser beam welding of 20 mm thick aluminum alloy with beam oscillation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yan, F.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhao, Z.S.; Wang, C.M. Investigation of collapse defect suppression in 20 mm-thick plate laser penetration welding via beam energy spatial control. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 151, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, F.; Gu, Y.; Cai, Y. Study on Optimization of Welding Process Parameters for Cast Aluminum A356 Based on Taguchi Method. Hot Work. Technol. 2016, 45, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter, R.; Ivanchev, L.; Burger, H.P. Effect of pre/post T6 heat treatment on the mechanical properties of laser welded SSM cast A356 aluminium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 447, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, D.H.; Decker, I.; Wohlfahrt, H. Laser Beam Welding of Aluminum Die Casting with Reduced Pore Formation; U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1994.

- Karami, S.; Yousefieh, M.; Naffakh-Moosavy, H. The effect of laser welding parameters on mechanical properties and microstructure evolution of multi-layered 6061 aluminum alloy. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2025, 11, 100275. [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri, V.; Cardaropoli, F.; Caiazzo, F.; Sergi, V. Investigation on porosity content in 2024 aluminum alloy welding by Yb:YAG disk laser. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 383–390, 6265–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.J.; Maijer, D.M.; Dancoine, L. Constitutive behavior of as-cast A356. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 548, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.J.; Maijer, D.M. Analysis and modelling of a rotary forming process for cast aluminium alloy A356. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 226, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trometer, N.; Chen, B.W.; Moodispow, M.; Cai, W.; Rinker, T.; Kamat, S.; Velasco, Z.; Luo, A.A. Modeling and validation of hydrogen porosity formation in aluminum laser welding. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 124, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Yang, S.L. Weld zone porosity elimination process in remote laser welding of AA5182-O aluminum alloy lap-joints. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 286, 116826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, T.E.; Zuhailawati, H.; Aizad, S.; Anasyida, A. Geometrical, microstructural and mechanical characterization of pulse laser welded thin sheet 5052-H32 aluminium alloy for aerospace applications. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.L.; Wang, G.; Xing, C.; Tan, C.W.; Jiang, J. Effect of process parameters on microstructure and properties of laser welded joints of aluminum/steel with Ni/Cu interlayer. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaiah, K.; Geetha, M.; Shanmugarajan, B.; Rao, S. Effect of welding speed on CO2 laser beam welded aluminum-magnesium alloy 5083 in H321 condition. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 685, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shao, J.; Han, L.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Z.; Miao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Bai, M. Investigation of the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Heat-Treatment-Free Die-Casting Aluminum Alloys Through the Control of Laser Oscillation Amplitude. Materials 2025, 18, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, M.; Burger, H.; Ivanchev, L.; Rooyen, C.V. Property and Quality Optimization of Laser Welded Rheo-Cast F357 Aluminum Alloy. Solid State Phenom. 2012, 192–193, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.R. Laser Beam Welding of Semi-Solid Rheocast Aluminium Alloy 2139. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1019, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.D.; Chen, Y.X.; Huang, H.; Gao, Z.Q.; Wang, Q.; Hou, L.F.; Wei, Y.H. Dual enhancement of wear and corrosion resistance in aluminum alloy anodic oxide films through glycerol addition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 711, 164071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, Z.A.; Safaei, B.; Asmael, M.; Kenevisi, M.S.; Sahmanl, S.; Karimzadeh, S.; Jen, T.C.; Hui, D. Impact of process parameters on mechanical and microstructure properties of aluminum alloys and aluminum matrix composites processed by powder-based additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 146, 79–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.N.; Song, Y.W.; He, K.Z.; Zhang, H.; Dang, K.H.; Cai, Y.; Han, E.H. Role of oxidants in the anodic oxidation of 2024 aluminum alloy by dominating anodic and cathodic processes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 703, 135229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ornek, C.; Nilsson, J.O.; Pan, J.S. Anodisation of aluminium alloy AA7075—Influence of intermetallic particles on anodic oxide growth. Corros. Sci. 2020, 164, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Slater, C.; Cai, H.; Hou, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q. Joining Technologies for Aluminium Castings—A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.; Faes, K.; De Waele, W.; Simar, A.; Verlinde, W.; Lezaack, M.; Sneyers, W.; Arnhold, J. A Review on the Weldability of Additively Manufactured Aluminium Parts by Fusion and Solid-State Welding Processes. Metals 2023, 13, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, H.X.; Zhao, Y.F.; Peng, Y.J.; Xu, M.J.; Chen, X.H. Interfacial bonding mechanisms in laser welding of 2024 Al alloy and continuous CFR-PEEK via adjustable ring-mode laser beam. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 153, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.Z.; Franciosa, P.; Ceglarek, D. Effect of focal position offset on joint integrity of AA1050 battery busbar assembly during remote laser welding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 2715–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.W.; Oliveira, J.P.; Yang, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, H.Y.; Xu, W.H.; Wu, L.Q.; Dou, T.Y.; Wang, R.J.; Tan, C.W.; et al. Effect of defocusing distance on interfacial reaction and mechanical properties of dissimilar laser Al/steel joints with a porous high entropy alloy coating. Mater. Charact. 2024, 210, 113751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.C.; Cheng, Y.H.; Zhang, X.C.; Yang, J.Y.; Yang, X.Y.; Cheng, Z.H. Simulation and experimental investigations on the effect of Marangoni convection on thermal field during laser cladding process. Optik 2020, 203, 164044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaziv, I.; Akselsen, O.M.; Ren, X.B.; Nyhus, B.; Eriksson, M. Laser Beam and Laser-Arc Hybrid Welding of Aluminium Alloys. Metals 2021, 11, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.W.; Zhu, T.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, B.L.; Yuan, H.W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Pan, H.J.; Liu, E.L. Microstructure and Hardness Analysis of Laser Welded A357 Semisolid Rheocasting Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, M.; Kah, P.; Hiltunen, E.; Martikainen, J. Effect of Al2O3 film on the mechanical properties of a welded high-strength (AW 7020) aluminium alloy. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2015, 230, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.W.; Wang, C.M.; Mi, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Oxygen content and morphology of laser cleaned 5083 aluminum alloy and its influences on weld porosity. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 140, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zheng, K.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, M. Effect of kerf characteristics on microstructures and properties of laser cutting–welding of AA2219 aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 4147–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiang, Q.Y.; Liu, W.J.; Ji, X.C.; Xing, F.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J. Effect of laser cleaning the anodized surface of 5083 aluminum alloy on weld quality. Weld. World 2024, 68, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Sato, S. Porosity reduction in CO2 laser welding of aluminium alloys-Influence of penetration, joint, oxygen gas and oxide films. Weld. Int. 2000, 14, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.X.; Kwakernaok, C.; Pan, Y.; Richardson, I.M.; Saldl, Z.; Kenjeres, S.; Kleijn, C. The effect of oxygen on transitional Marangoni flow in laser welding. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 3154–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.W.; Zanella, C. Hardness and corrosion behaviour of anodised Al-Si produced by rheocasting. Mater. Des. 2019, 173, 107764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.W.; Fedel, M.; Andersson, N.; Leiosner, P.; Deflorian, F.; Zanella, C. Effect of Si Content and Morphology on Corrosion Resistance of Anodized Cast Al-Si Alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Lu, Y.; Miao, J.S.; Klarner, A.; Yan, X.Y.; Luo, A.A. Predicting grain structure in high pressure die casting of aluminum alloys: A coupled cellular automaton and process model. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 161, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourret, D.; Karma, A. Growth competition of columnar dendritic grains: A phase-field study. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Guan, Z.P.; Yang, H.Y.; Dang, B.X.; Zhang, L.C.; Meng, J.; Luo, C.J.; Wang, C.G.; Cao, K.; Qiao, J.; et al. Sub-rapid solidification microstructure characteristics and control mechanisms of twin-roll cast aluminum alloys: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 874–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.F.; Ali, Y.; You, G.Q.; Zhang, M.X. Effect of cooling rate on grain refinement of cast aluminium alloys. Materialia 2018, 3, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwema, F.M.; Akinlabi, E.T.; Oladijo, O.P.; Krishna, S.; Majumdar, J.D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of sputtered Aluminum thin films. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 35, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shi, Y.; Guo, J.C.; Volodymyr, K.; Le, W.Y.; Dai, F.X. Porosity inhibition of aluminum alloy by power-modulated laser welding and mechanism analysis. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 102, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.Q.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Yi, H.L.; Xie, G.M. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of laser-welded novel Al-Si coated 2 GPa press-hardened steel by weld alloying. Mater. Charact. 2025, 228, 115444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.J.; Ganguly, W.; Suder, W. Study on effect of laser keyhole weld termination regimes and material composition on weld overlap start-stop defects. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 57, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehryar Khan, M.; Shahabad, S.I.; Yavuz, M.; Duley, W.W.; Biro, E.; Zhou, Y. Numerical modelling and experimental validation of the effect of laser beam defocusing on process optimization during fiber laser welding of automotive press-hardened steels. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 67, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indhu, R.; Manish, T.; Vijayaraghavan, L.; Soundarapandian, S. Microstructural evolution and its effect on joint strength during laser welding of dual phase steel to aluminium alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Si | Mg | Fe | Cu | Mn | Zn | Ti | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.84 | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 | Balance |

| Welding Speed (m/min) | Defocusing Amount (mm) | Surface Oxidation Conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 0 | No anodized film (NAF) |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | Single-sheet with anodized films on both upper and lower surfaces (SSAF-U/L) |

| 3 | 4 | 0 | Double-sheet with anodized films on both upper and lower surfaces (DSAF-U/L) |

| 4 | 4 | 0 | Double-sheet with anodized films on the upper surface only (DASF-U) |

| 5 | 4 | +! | No anodized film (NAF) |

| 6 | 4 | +1 | Single-sheet with anodized films on both upper and lower surfaces (SSAF-U/L) |

| 7 | 4 | +1 | Double-sheet with anodized films on both upper and lower surfaces (DSAF-U/L) |

| 8 | 3 | 0 | No anodized film (NAF) |

| 9 | 3 | 0 | Single-sheet with anodized films on both upper and lower surfaces (SSAF-U/L) |

| 10 | 3 | 0 | Double-sheet with anodized films on both upper and lower surfaces (DSAF-U/L) |

| Group Number | Upper Weld Seam Width (mm) | Lower Weld Seam Width (mm) | FZ Area | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (4 m/min, 0 mm, NAF) | 4015.16 | 3172.55 | 7.59 | 3.09 |

| 2 (4 m/min, 0 mm, SSAF-U/L) | 4138.53 | 3446.93 | 7.19 | 4.62 |

| 3 (4 m/min, 0 mm, DSAF-U/L) | 3762.95 | 3379.87 | 7.14 | 6.71 |

| 4 (4 m/min, 0 mm, DASF-U) | 3858.13 | 3249.13 | 7.11 | 5.25 |

| 5 (4 m/min, +1 mm, NAF) | 4027.31 | 3168.38 | 7.20 | 4.01 |

| 6 (4 m/min, +1 mm, SSAF-U/L) | 3649.58 | 3414.93 | 7.06 | 4.94 |

| 7 (4 m/min, +1 mm, DSAF-U/L) | 3802.47 | 2439.60 | 6.24 | 8.64 |

| 8 (3 m/min, 0 mm, NAF) | 4867.54 | 4689.56 | 9.56 | 4.62 |

| 9 (3 m/min, 0 mm, SSAF-U/L) | 4787.98 | 3589.92 | 8.38 | 5.56 |

| 10 (3 m/min, 0 mm, DSAF-U/L) | 4793.20 | 3463.46 | 8.26 | 9.25 |

| 0–10 µm (%) | 10–20 μm (%) | 20 μm or More (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAF | 57.17 | 14.26 | 28.57 |

| SSAF | 10.00 | 30.00 | 60.00 |

| DSAF | 0 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | ||||||

| 1 | BM | BM | BM | BM | BM | |

| 2 | FZ | HAZ | FZ | HAZ | HAZ | |

| 3 | BM | BM | BM | BM | BM | |

| 4 | BM | BM | BM | BM | BM | |

| 5 | BM | BM | BM | BM | HAZ | |

| 6 | HAZ | BM | BM | BM | FZ | |

| 7 | BM | BM | BM | BM | BM | |

| 8 | FZ | HAZ | FZ | FZ | BM | |

| 9 | BM | BM | BM | HAZ | HAZ | |

| 10 | BM | BM | BM | BM | BM | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, B.; Yuan, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Feng, T.; Liu, E. Effect of Anodizing and Welding Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded A356 Alloy. Coatings 2025, 15, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121461

Zhu B, Yuan H, Liu J, Chen G, Feng T, Liu E. Effect of Anodizing and Welding Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded A356 Alloy. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121461

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Baiwei, Hongwei Yuan, Jun Liu, Gong Chen, Tianyun Feng, and Erliang Liu. 2025. "Effect of Anodizing and Welding Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded A356 Alloy" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121461

APA StyleZhu, B., Yuan, H., Liu, J., Chen, G., Feng, T., & Liu, E. (2025). Effect of Anodizing and Welding Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded A356 Alloy. Coatings, 15(12), 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121461