Evaluation of the Inhibitory Efficiency of Yohimbine on Corrosion of OLC52 Carbon Steel and Aluminum in Acidic Acetic/Acetate Media

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Electrochemical Methods

2.3. Molecular Modeling

3. Results

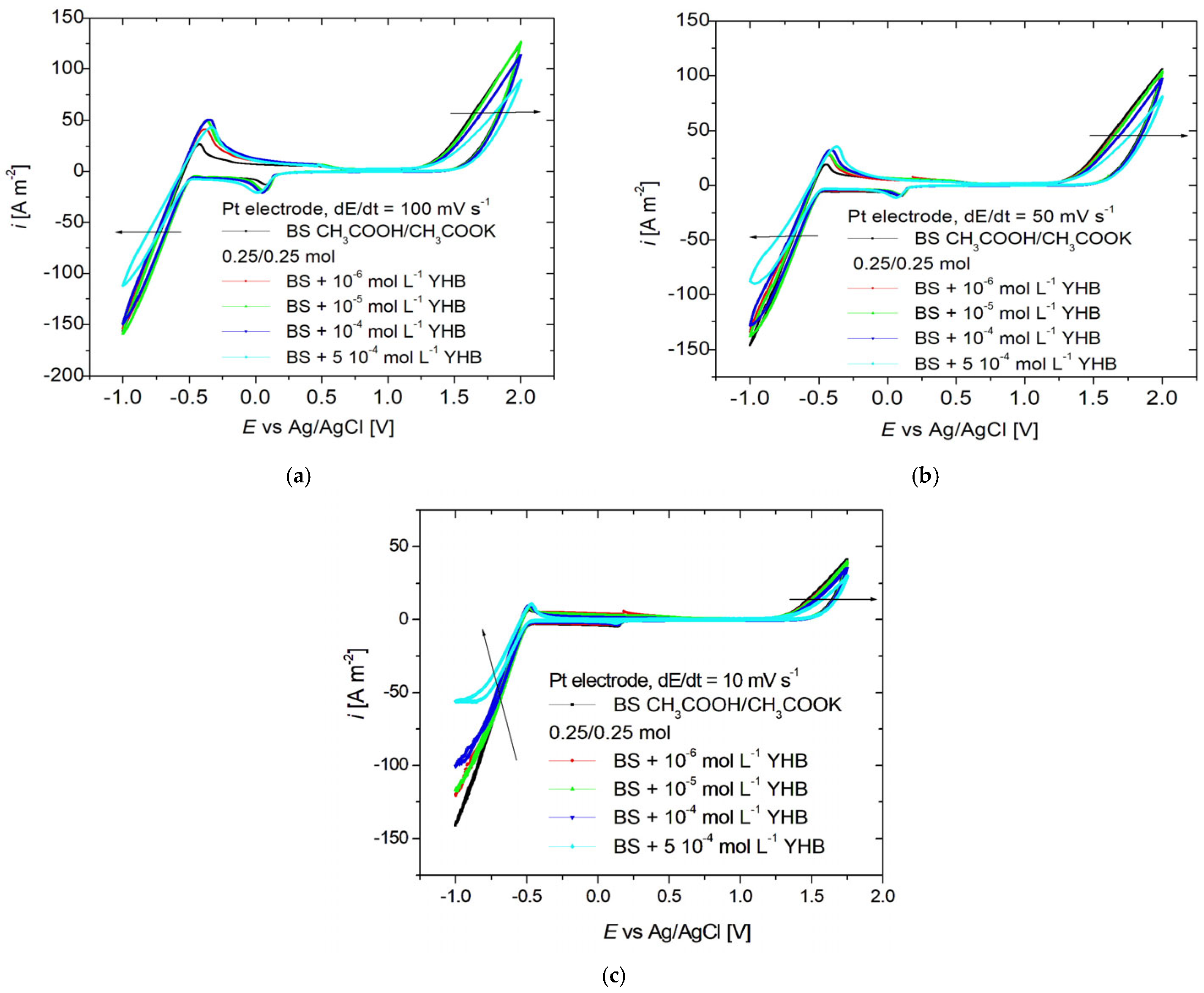

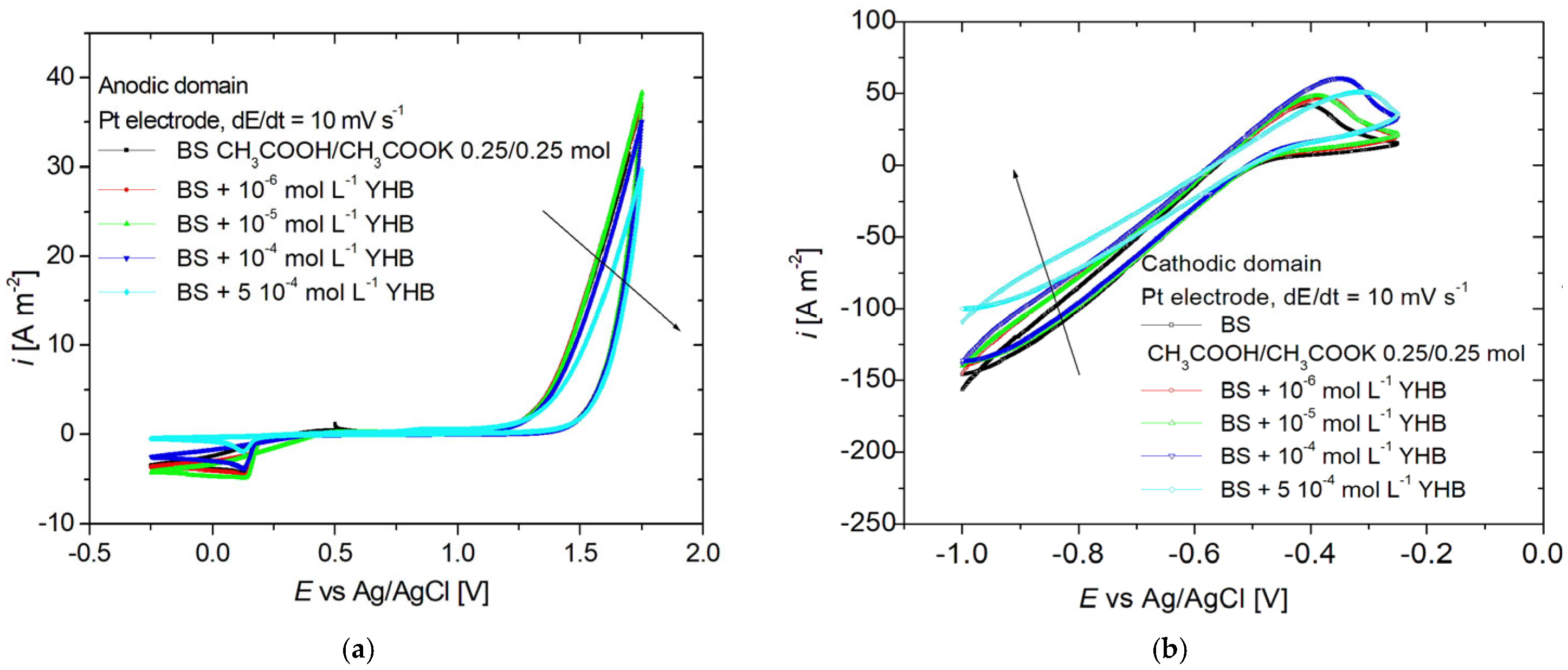

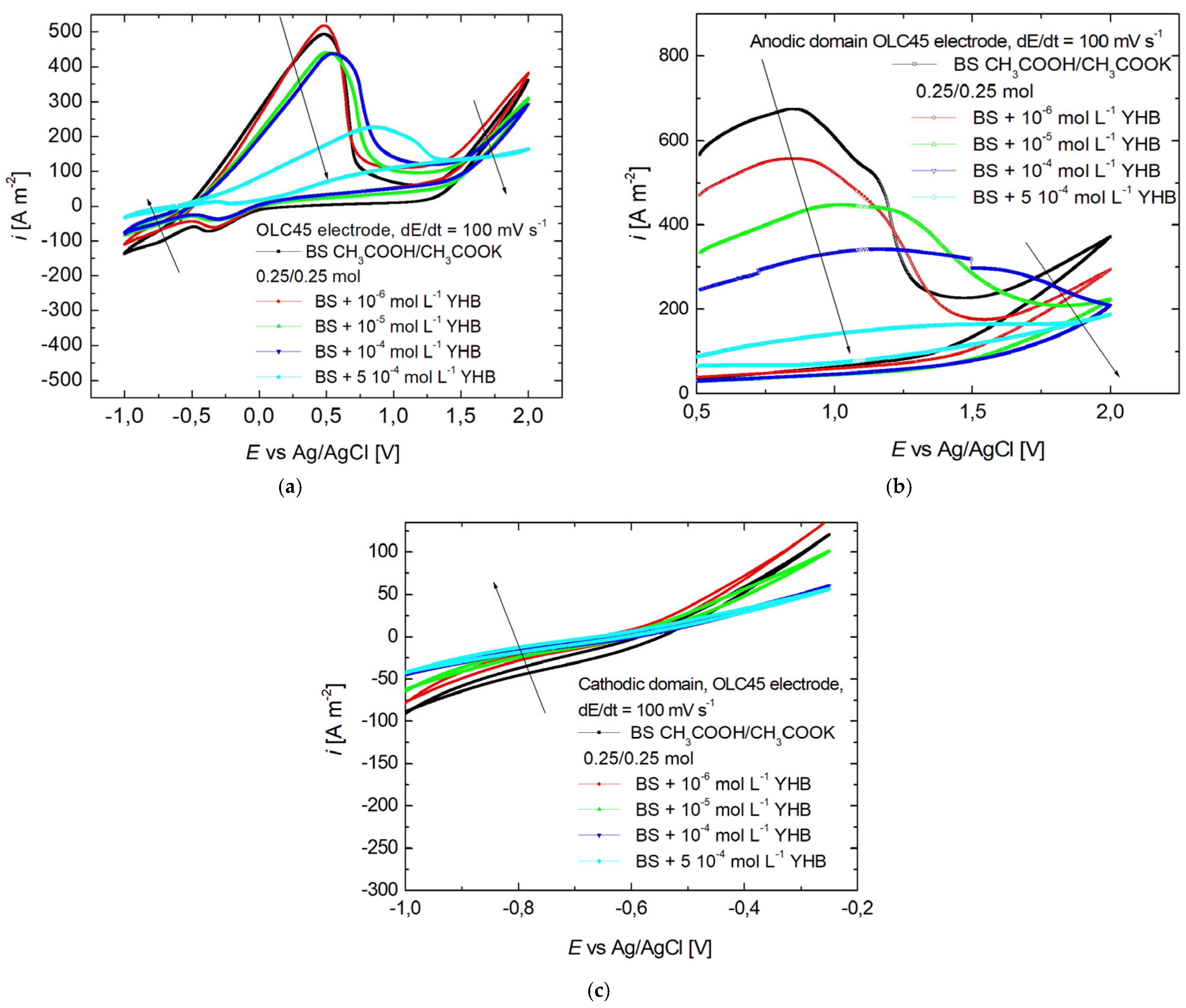

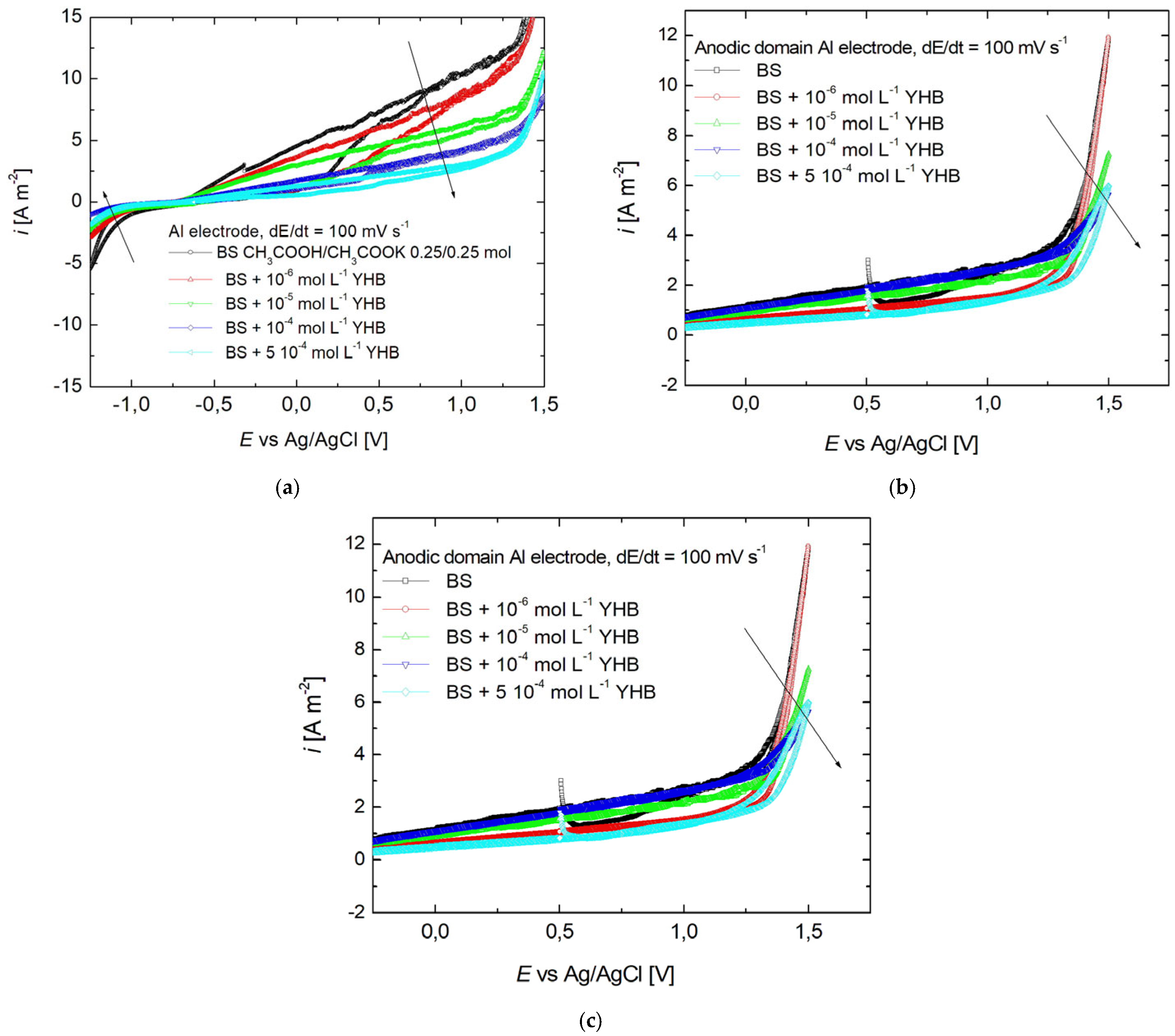

3.1. Cyclic Voltammetry

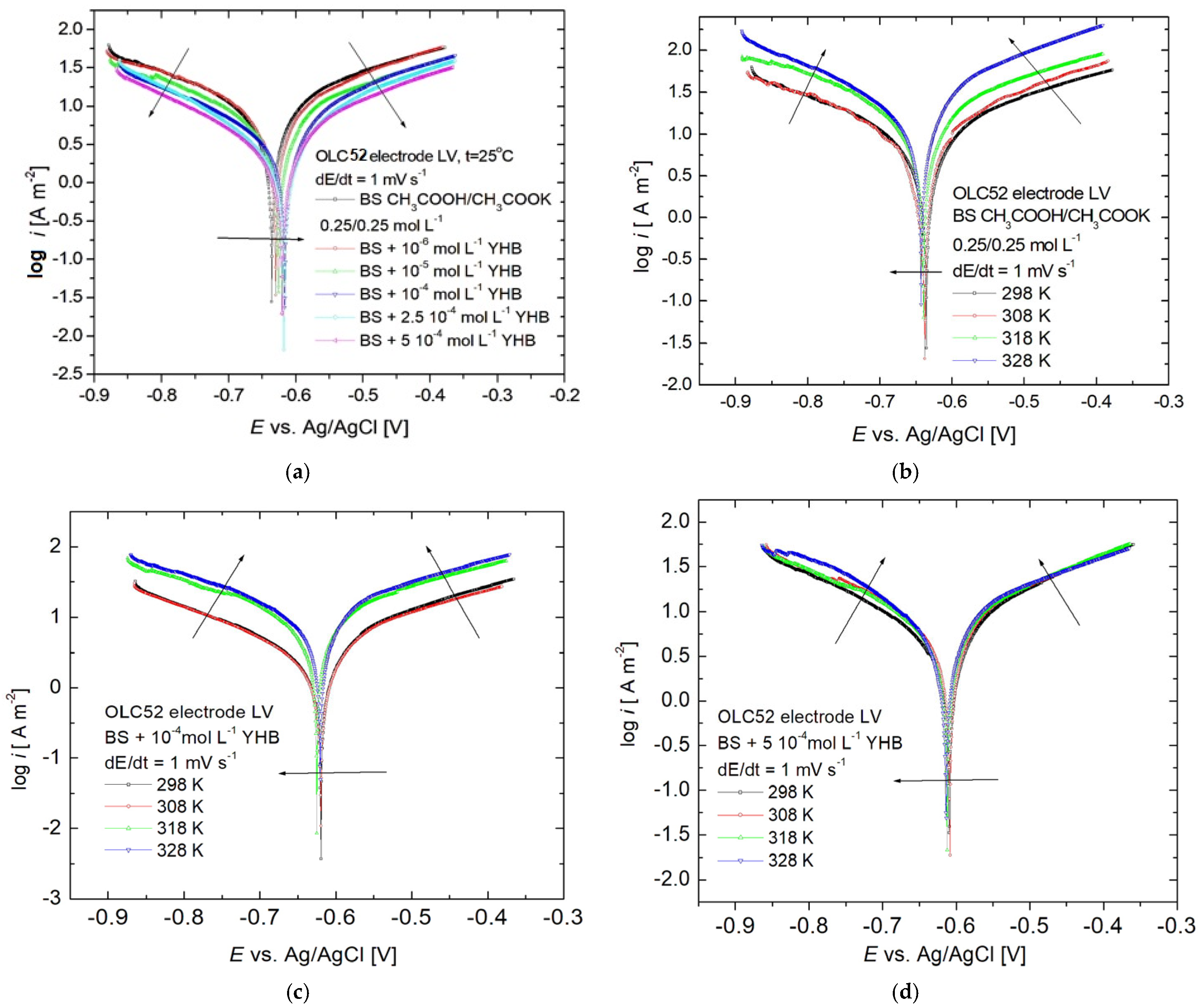

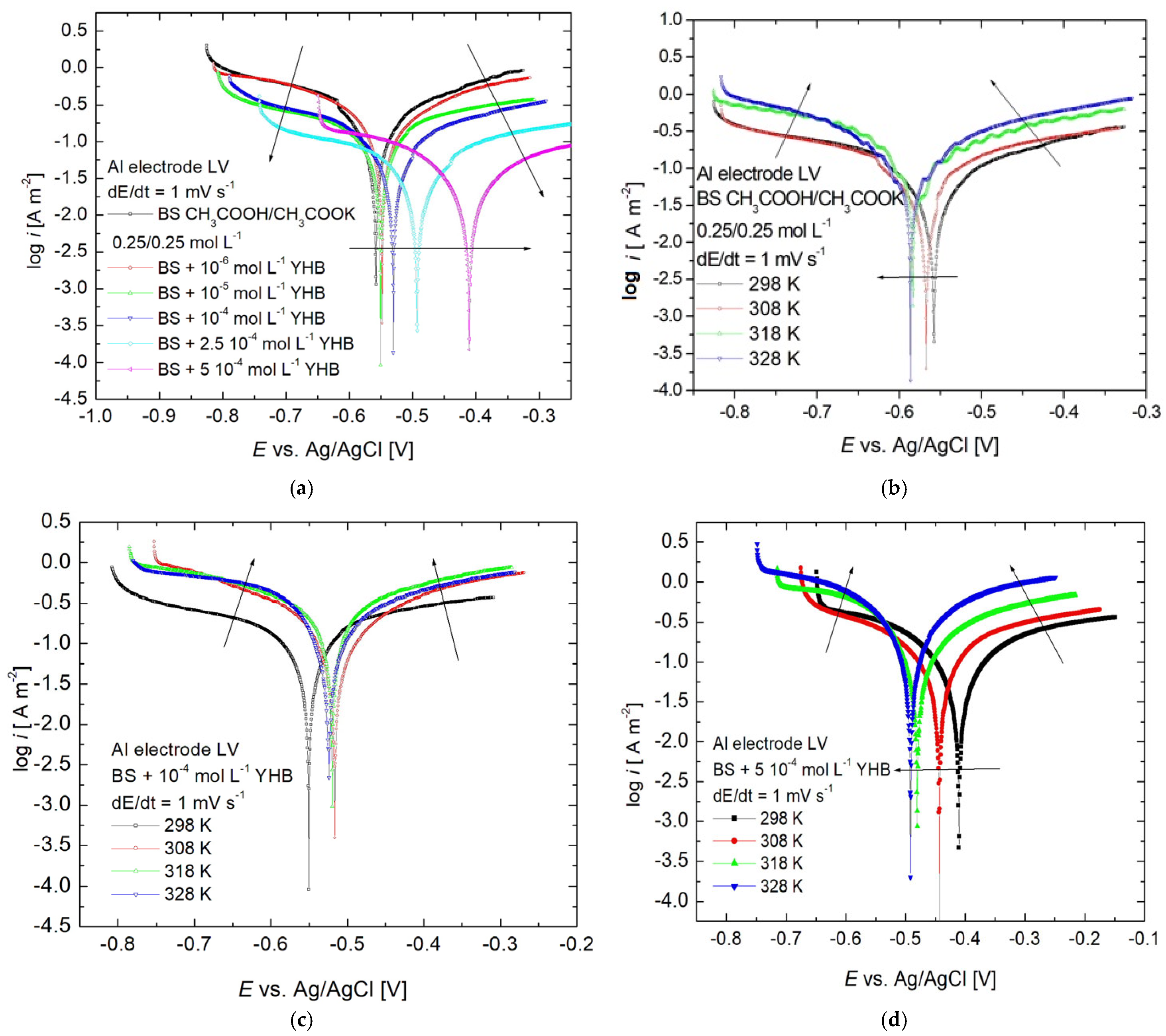

3.2. Linear Sweep Voltammetry

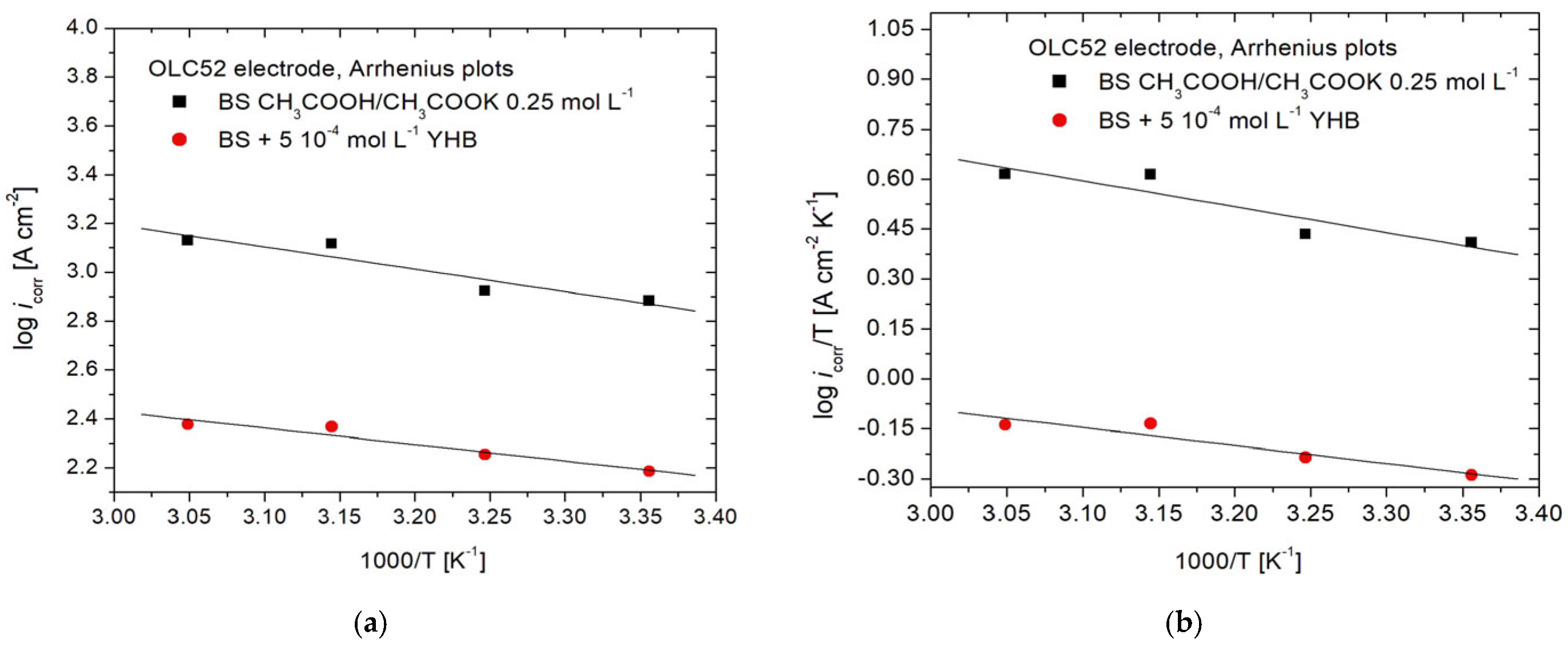

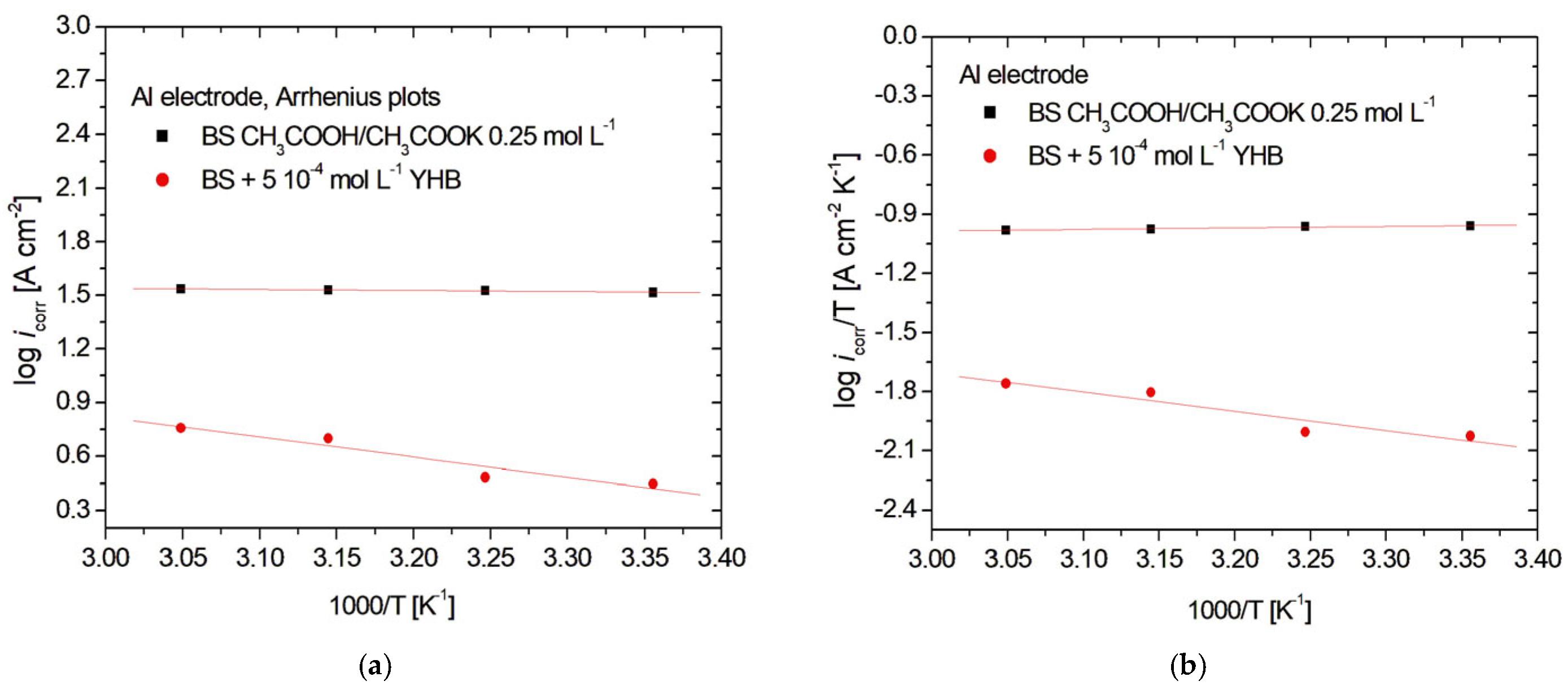

3.3. Arrhenius and Eyring Plots

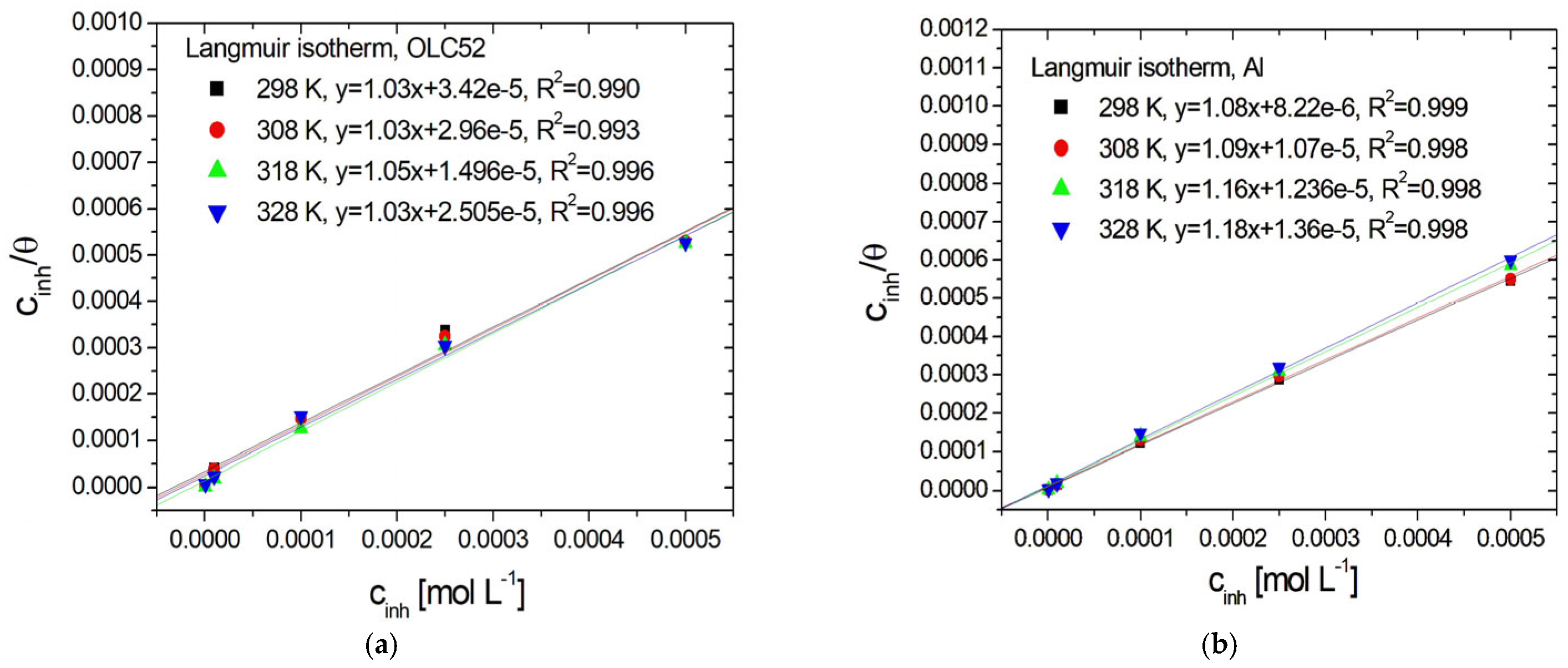

3.4. Adsorption Isotherms

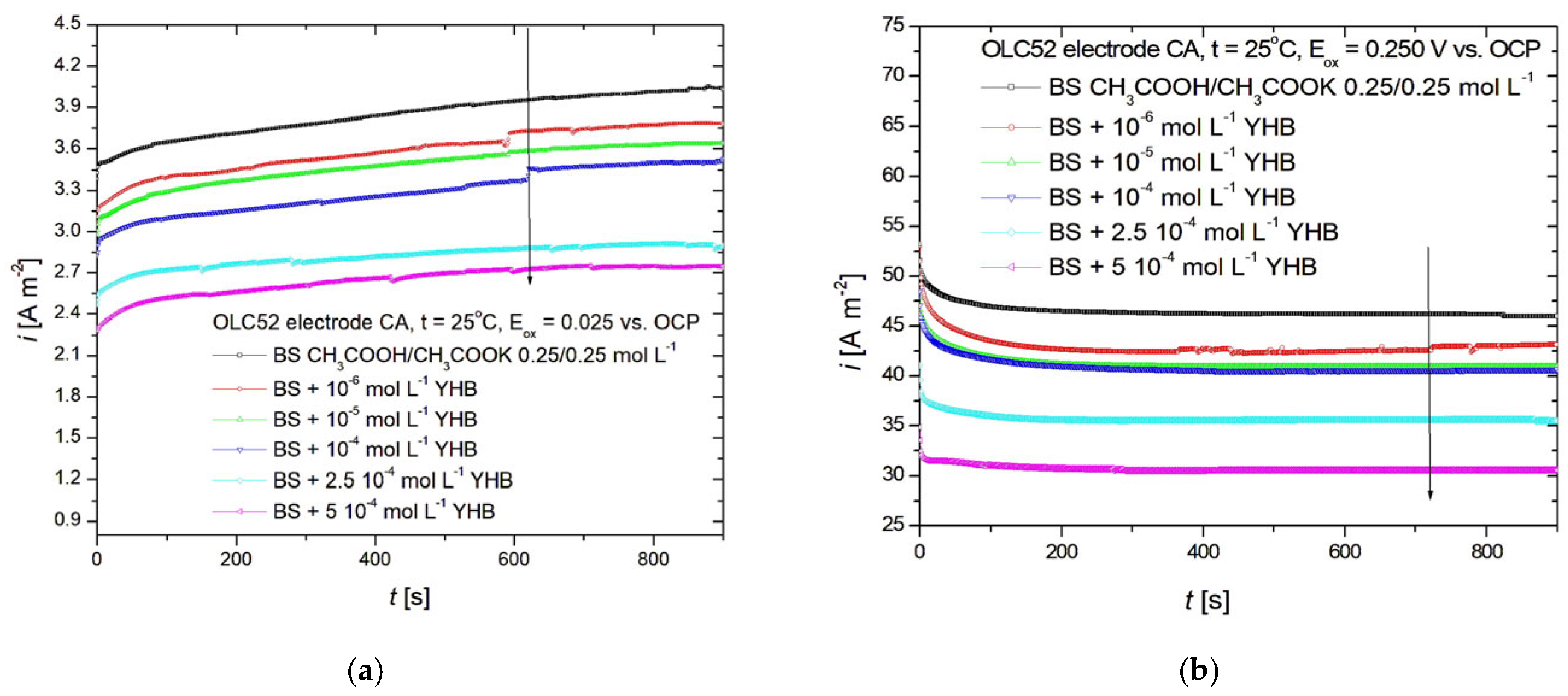

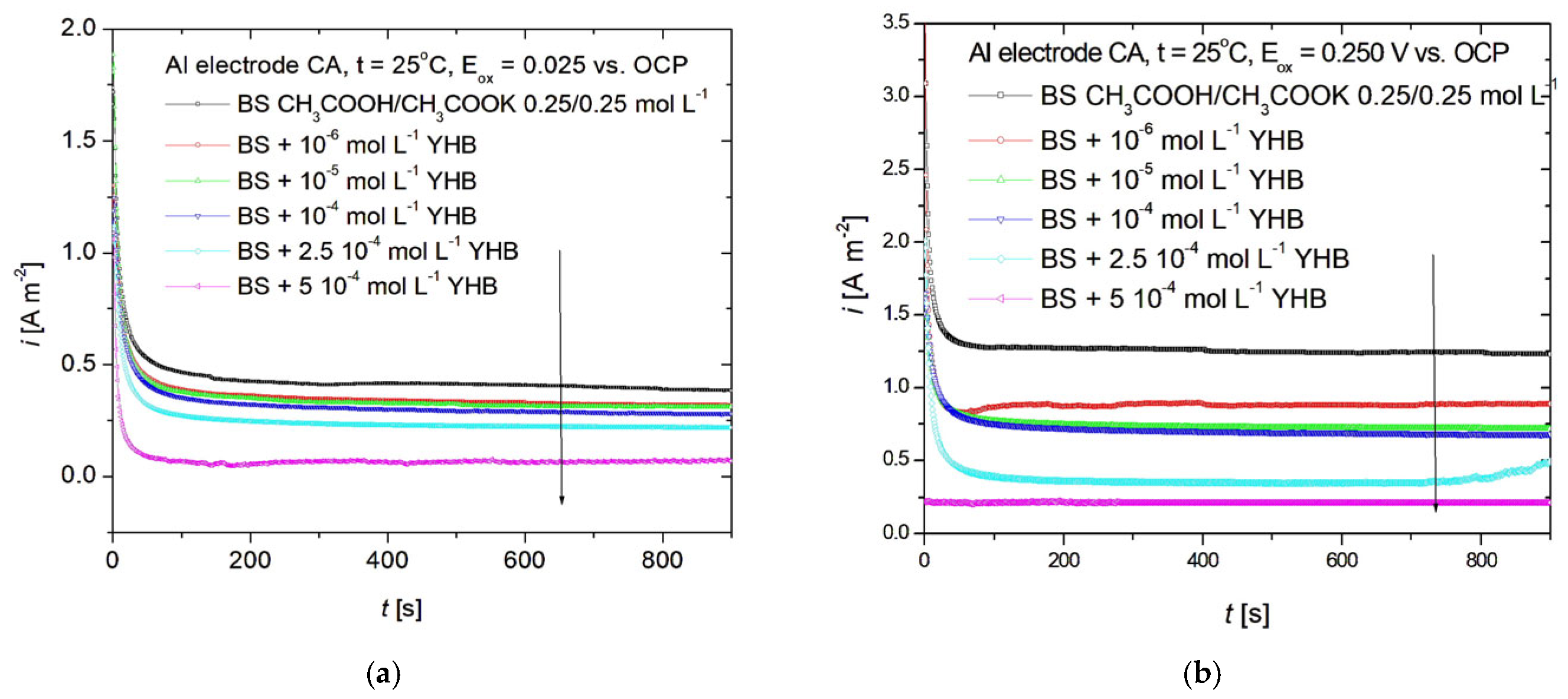

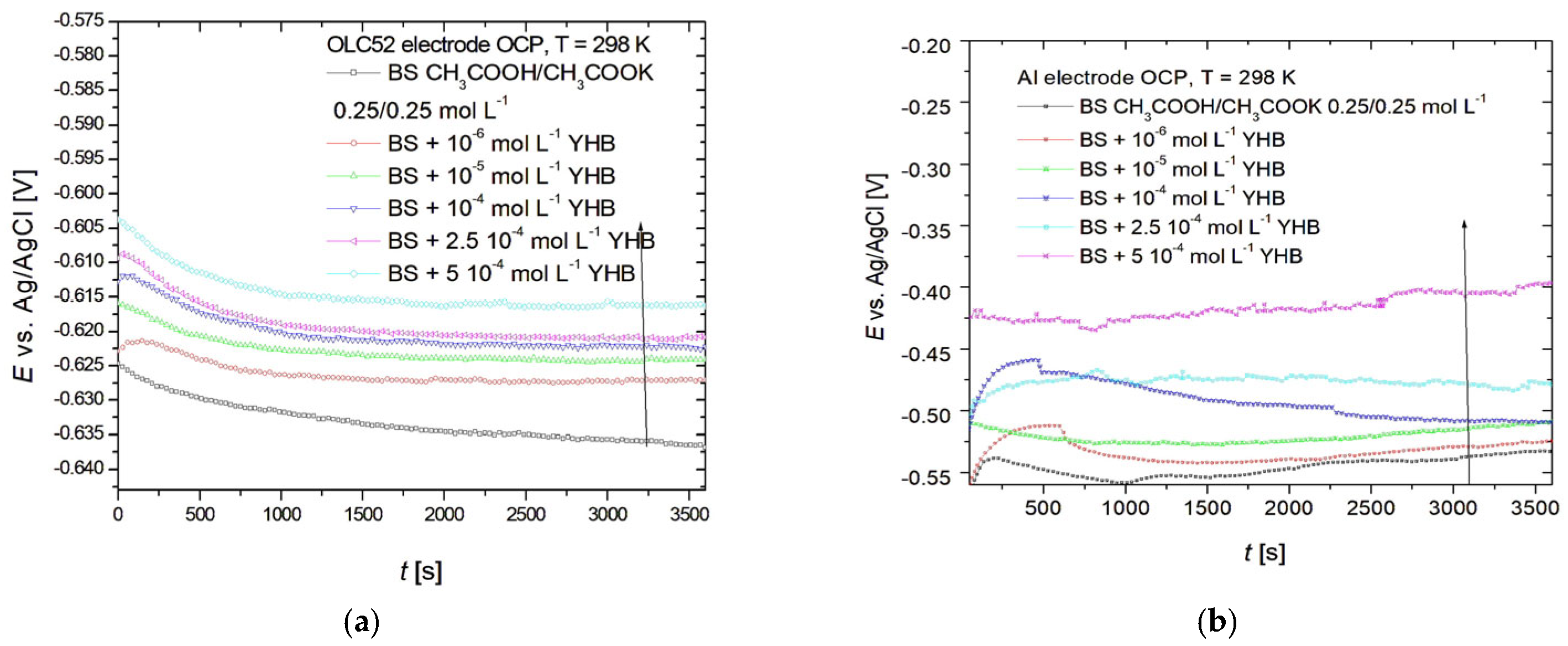

3.5. Chronoampherometry Studies

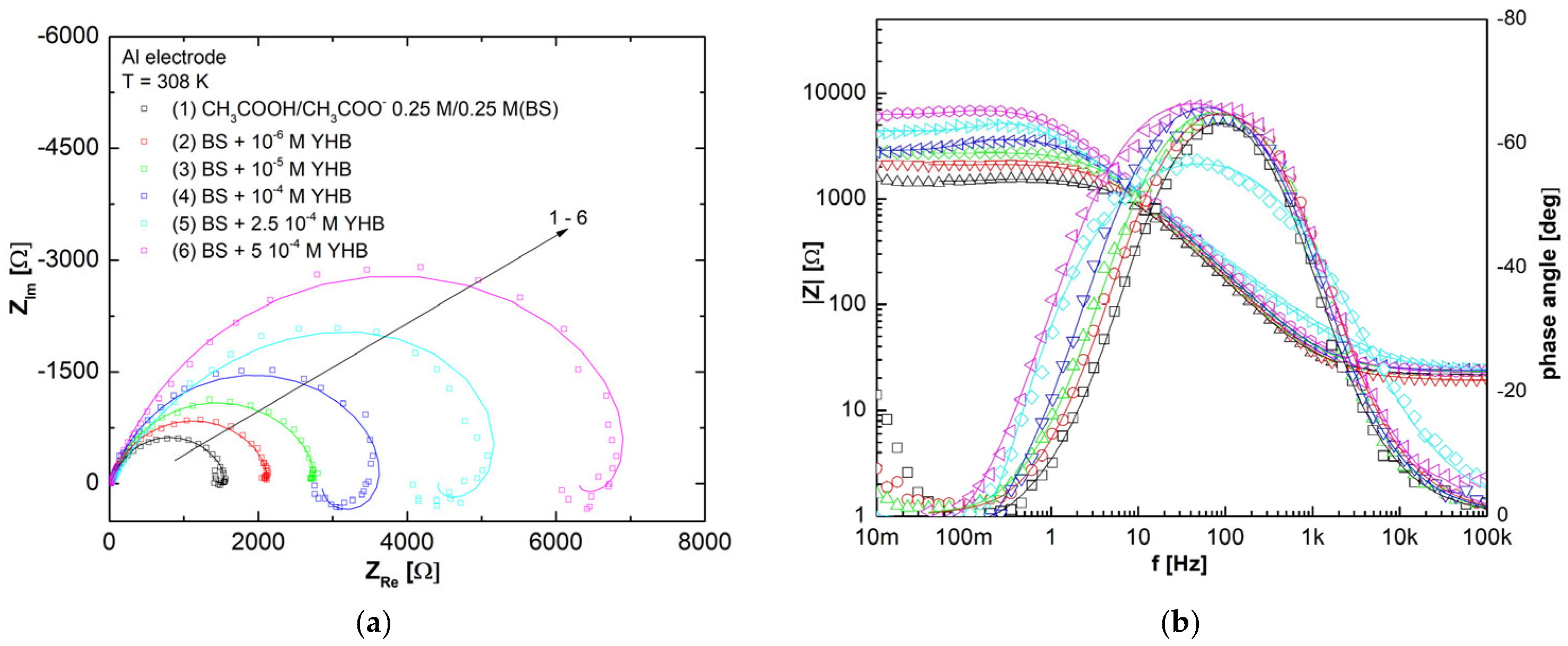

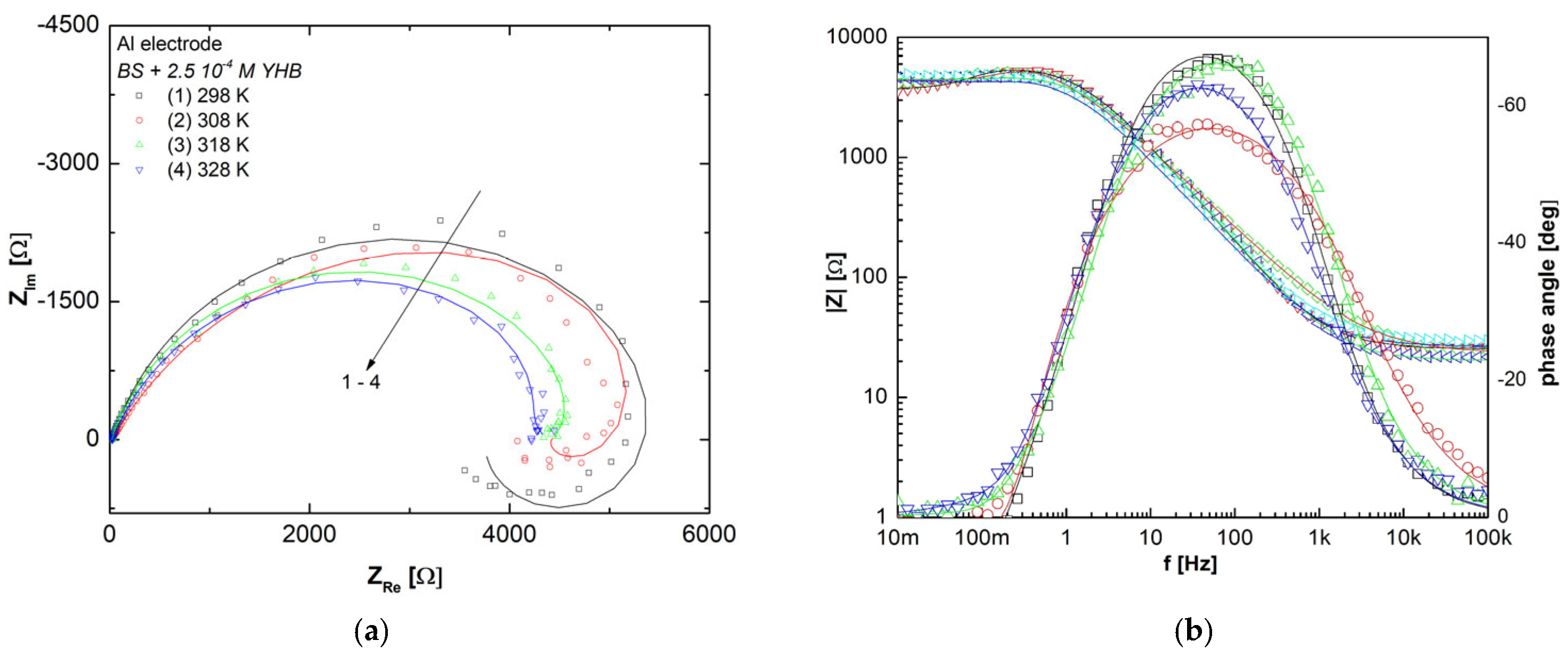

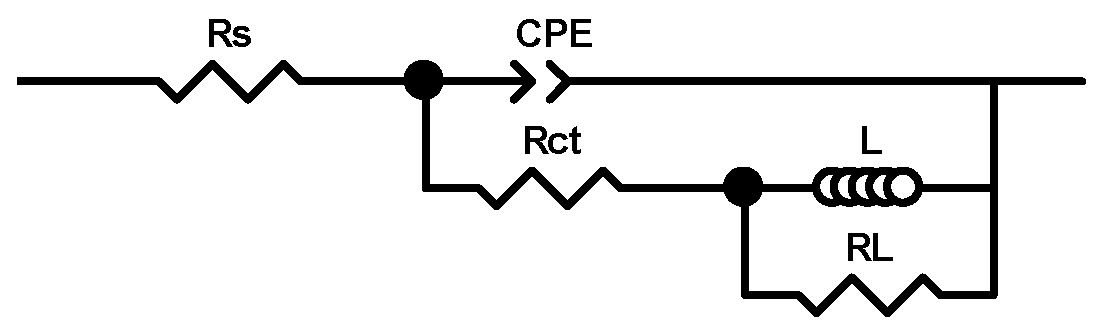

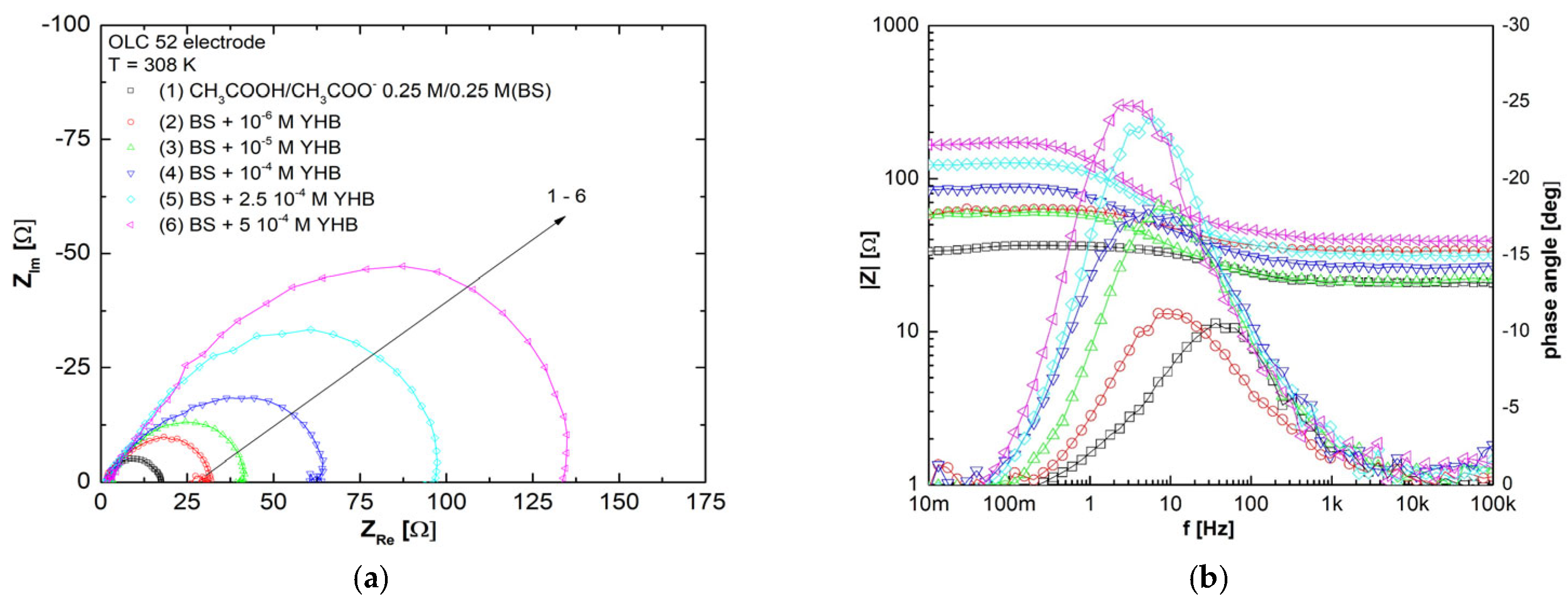

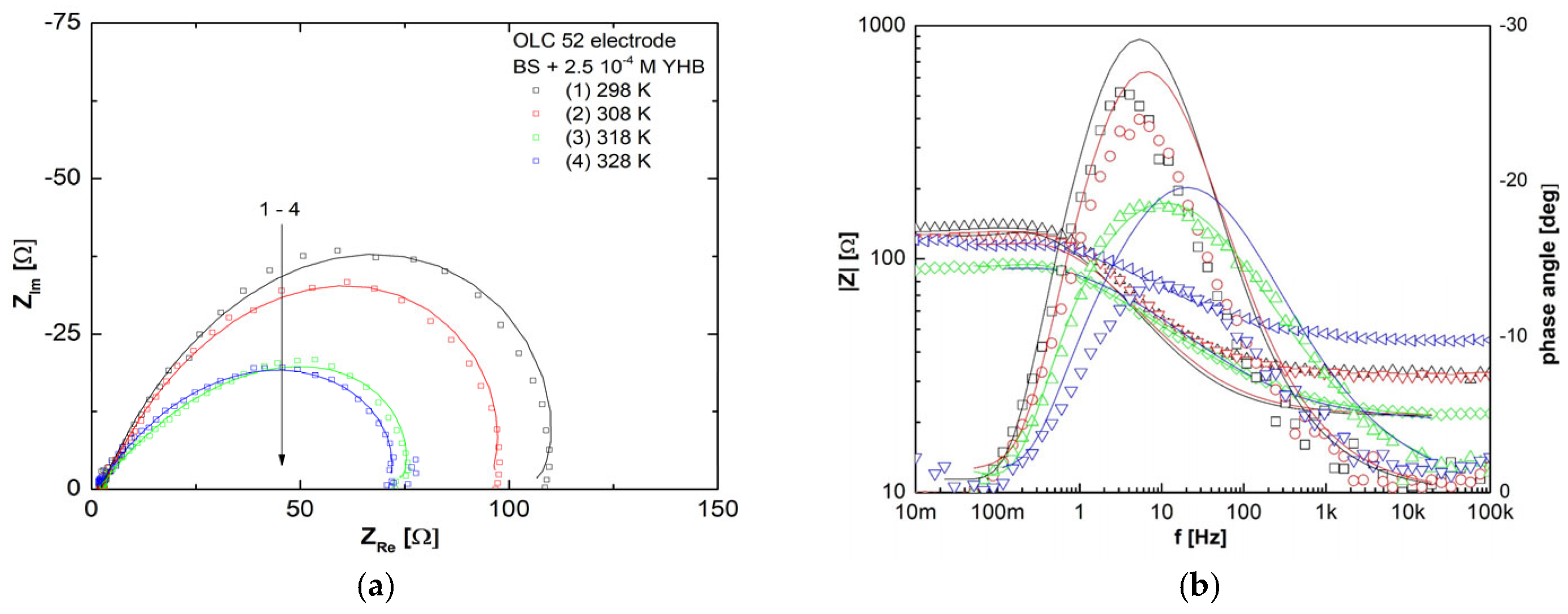

3.6. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Studies

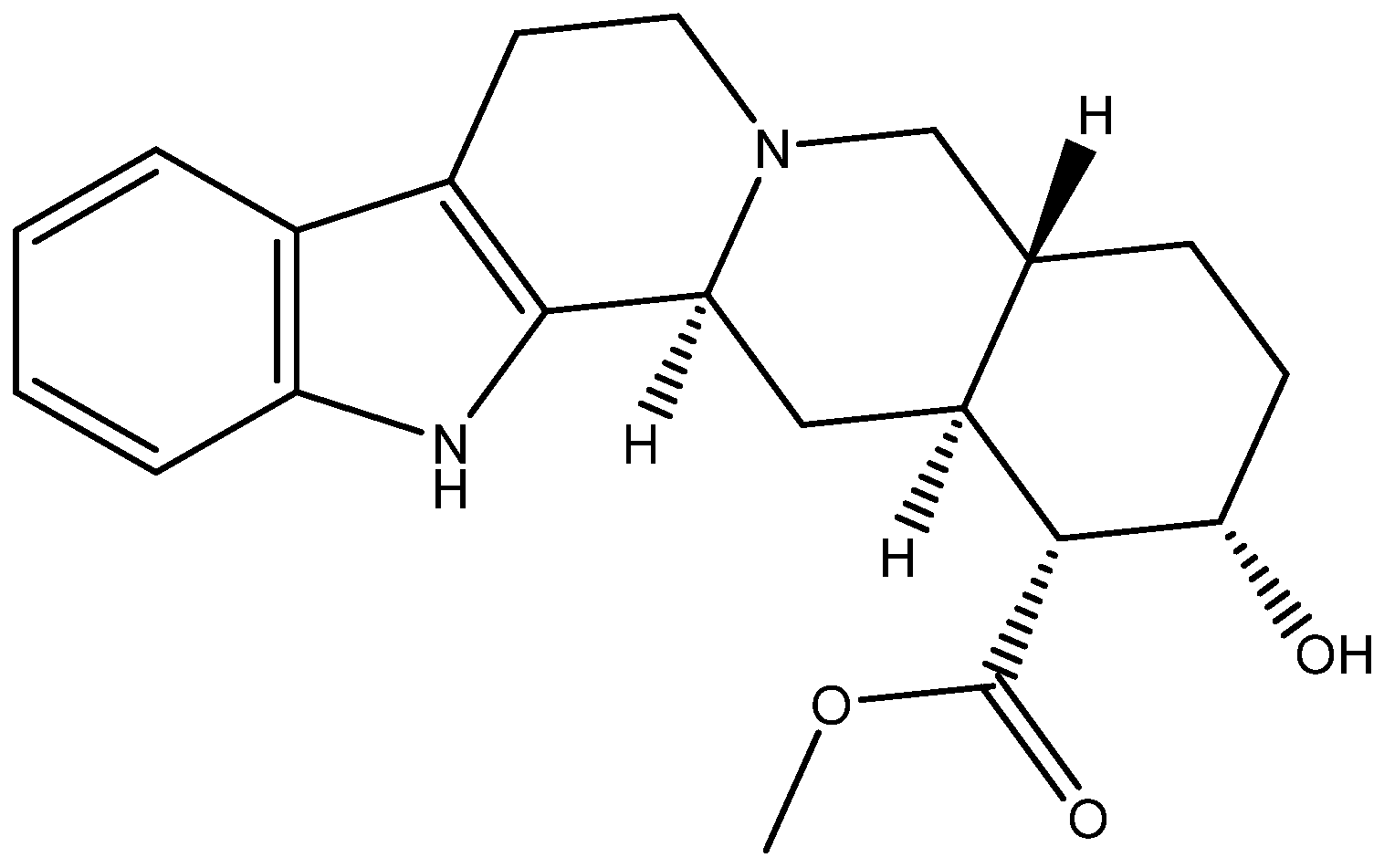

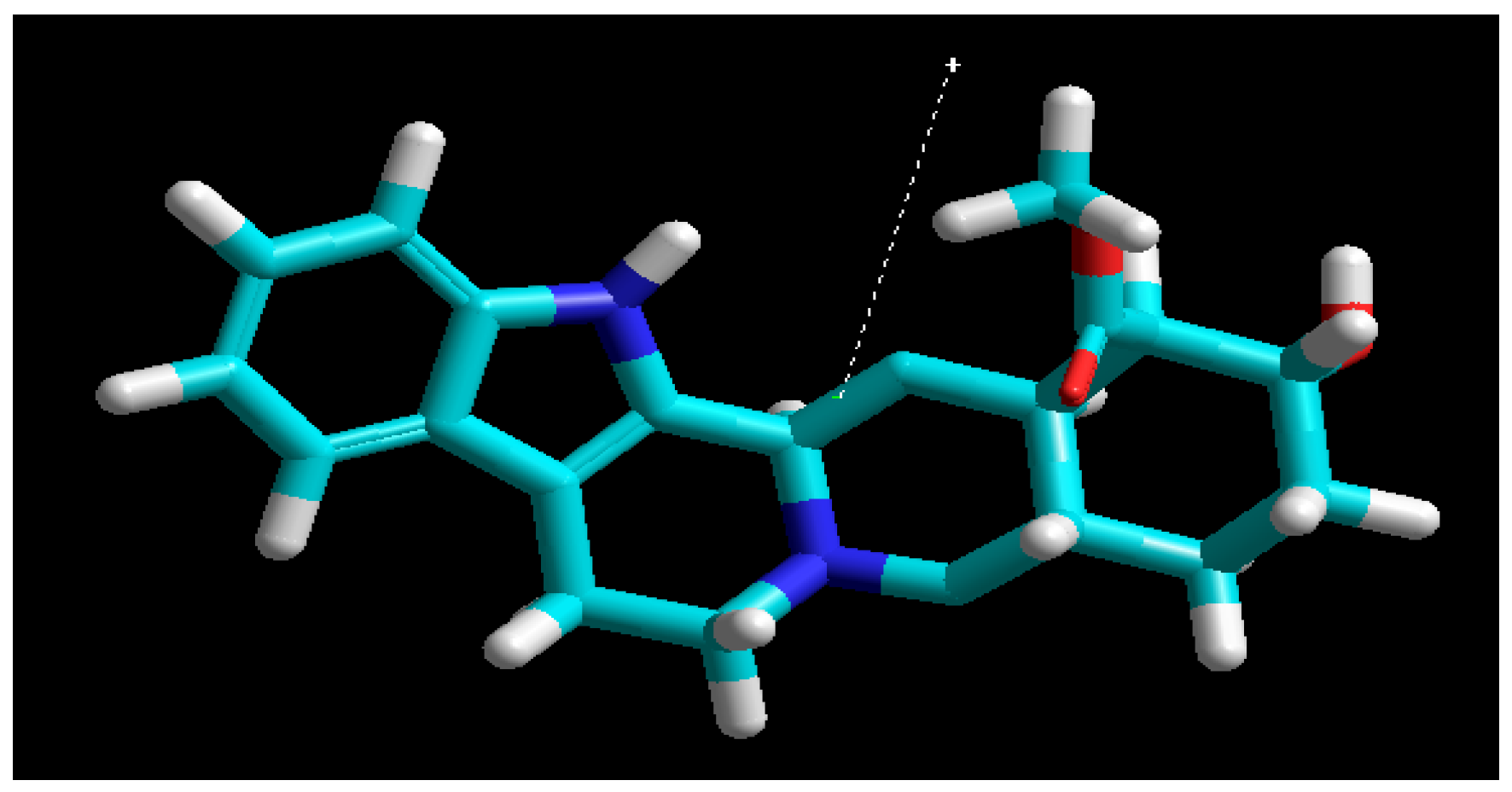

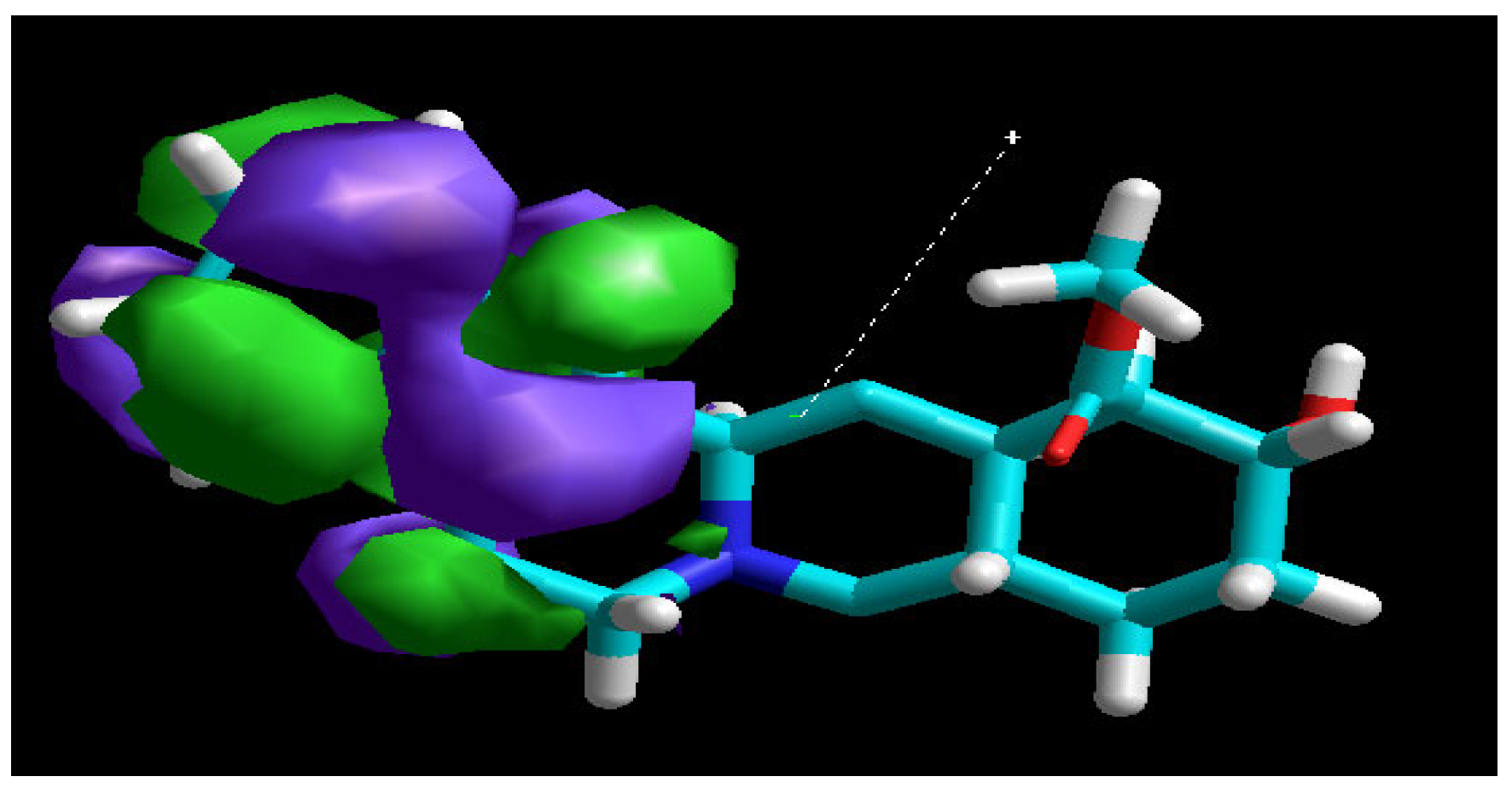

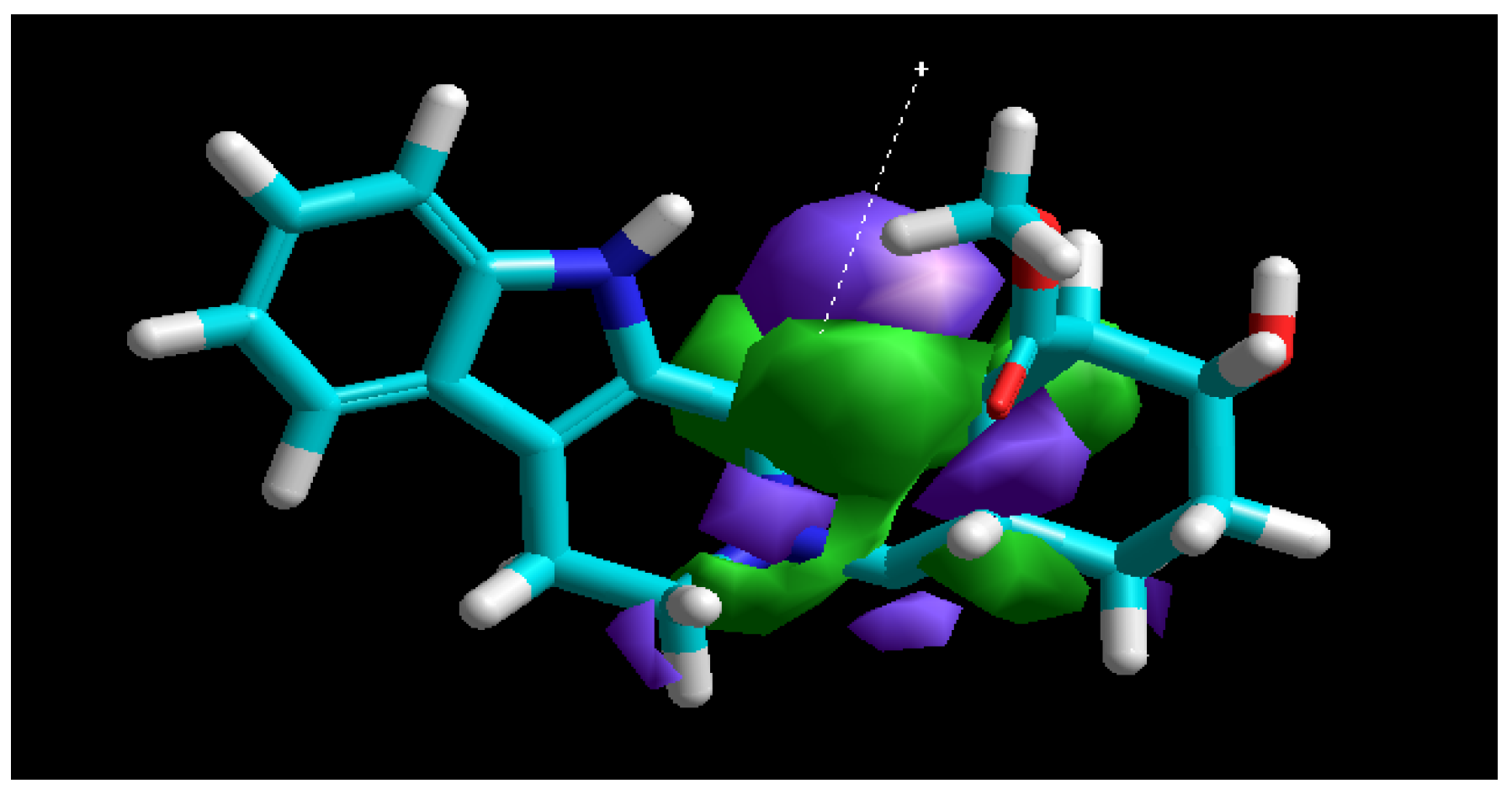

3.7. Molecular Modeling

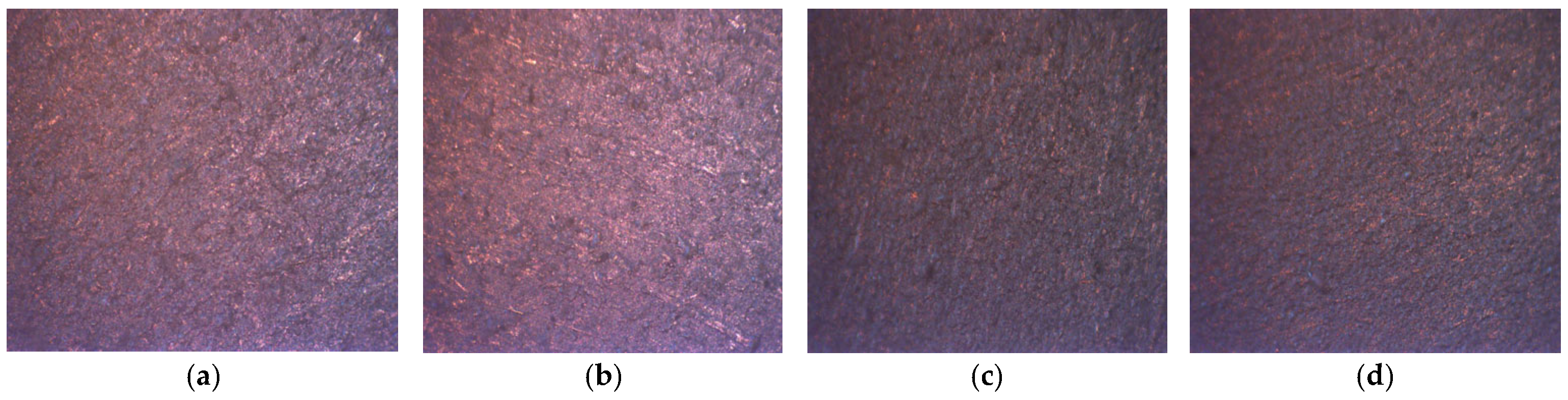

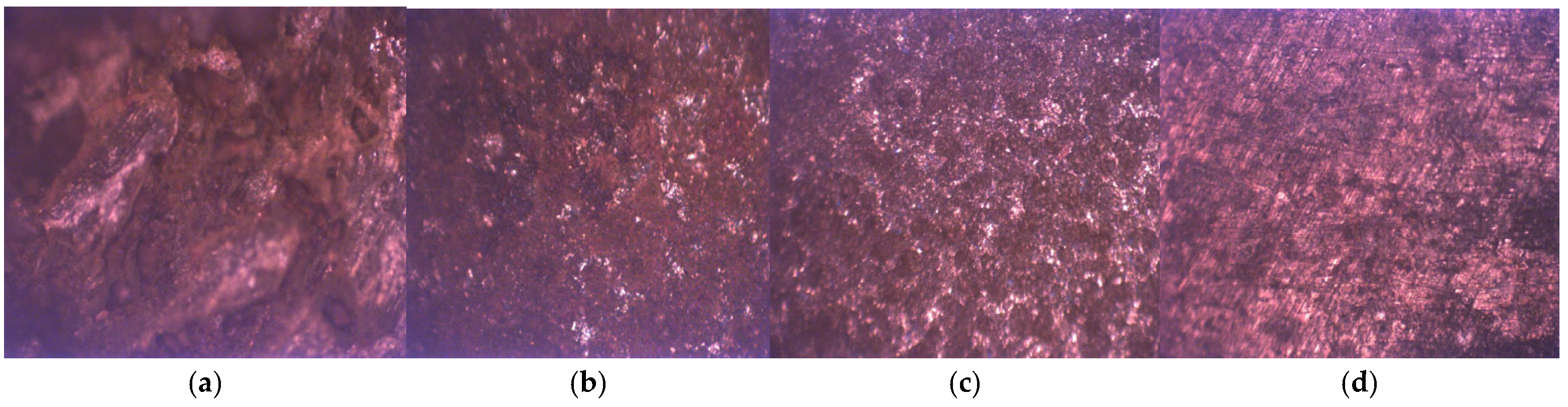

3.8. Surface Morphology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dalbouha, A.; Rais, Z. Metal Corrosion: In-depth Analysis, Economic Impacts and Inhibition Strategies for Enhanced Infrastructure Durability. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Stud. 2022, 5, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, U.M. A Critical Review of the Science and Engineering of Cathodic Protection of Steel in Soil and Concrete. Corrosion 2019, 75, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, P.; Pawar, C.; Avhad, M.; More, A. Corrosion Inhibitors for Carbon Steel: A Review. Vietnam J. Chem. 2022, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Jin, M.; Yan, Y.; Tang, J.; Jin, Z. A Review of Organic Corrosion Inhibitors for Resistance under Chloride Attacks in Reinforced Concrete: Background, Mechanisms and Evaluation Methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 433, 136583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, A.; Bahmani, E.; Rouh Aghdam, A.S. Plant extracts as sustainable and green corrosion inhibitors for protection of ferrous metals in corrosive media: A mini review. Corros. Commun. 2022, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungwari, C.P.; Obadele, B.A.; King’ondu, C.K. Phytochemicals as Green and Sustainable Corrosion Inhibitors for Mild Steel and Aluminium: Review. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 18, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrini, M. Alkaloids from Plant Extracts as Corrosion Inhibitors for Metal Alloys. In Alkaloids—Recent Advances and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, D.Q.; Huong, N.T.L.; Nguyet, T.T.A.; Duong, T.; Tuan, D.; Thong, N.M.; Nam, P.C. Pivotal Role of Heteroatoms in Improving the Corrosion Inhibition Ability of Thiourea Derivatives. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 27655–27666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydaei, M. The Use of Plant Extracts as Green Corrosion Inhibitors: A Review. Surfaces 2024, 7, 380–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, B.; Raut, B.K.; Bhattarai, S.; Bhandari, S.; Tandan, P.; Gyawali, K.; Sharma, K.; Ranabhat, D.; Thapa, R.; Aryal, D.; et al. Potential Therapeutic Applications of Plant-Derived Alkaloids against Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2022, 7299778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrini, M.; Robert, F.; Roos, C. Alkaloids Extract from Palicourea guianensis Plant as Corrosion Inhibitor for C38 Steel in 1 M Hydrochloric Acid Medium. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2011, 6, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, E.E.; Alrashdi, S.; Boraei, A.T.A.; Eid, S.; Gomaa, I.; Gad, E.S.; Elhenawy, A.A.; Nady, H. Utilizing Some Indole Derivatives to Control Mild Steel Corrosion in Acidic Environments: Electrochemical and Theoretical Methods. Molecules 2025, 30, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowacka, A.; Śniegocka, M.; Śniegocki, M.; Ziółkowska, E.; Bożiłow, D.; Smuczyński, W. Multifaced Nature of Yohimbine—A Promising Therapeutic Potential or a Risk? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, L.; Shi, X. Environmental Impacts of Chemicals for Snow and Ice Control: State of the Knowledge. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2012, 223, 2751–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proviron Industries, N.V. Provifrost KA ECO (Potassium Acetate) Safety Data Sheet; Version 0.2, 17 January 2013 (rev. 2 April 2015). 2015. Available online: https://www.premierdeicers.co.uk/downloads/MSDS%20Provifrost%20KA%20ECO%20%28eng%29.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Kuokkala, V.-T.; Kokkonen, J.; Paajanen, H. Corrosion Behaviour of Aircraft Coating Systems in Acetate- and Formate-Based De-Icing Chemicals. Mater. Corros. 2009, 60, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiuzhou, L.; Wei, Z.; Feng, Y.; Han, Y.; Qiang, P.; Yongjun, M.; Yuhao, W.; Baojie, D. Corrosion Electrochemical Behavior of 2024 Aluminum Alloy in Potassium Acetate Deicing Fluid. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2023, 34, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, K.; Ada, H.D.; Kilicaslan, N.; Gök, A. A Review of CFD Modeling of Erosion-Induced Corrosion Formation in Water Jets Using FEA. J. Mech. Mater. Mech. Res. 2023, 6, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gece, G. The use of quantum chemical methods in corrosion inhibitor studies. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 2981–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenso, E.E.; Kabanda, M.M.; Arslan, T.; Saracoglu, M.; Kandemirli, F.; Murulana, L.C.; Singh, A.K.; Shukla, S.K.; Hammouti, B.; Khaled, K.F. Quantum chemical investigations on quinoline derivatives as effective corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 5643–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Dayyih, W.; Mallah, E.; Awad, R.; Mansoor, K.; Arafat, T.; Al-Akayleh, F.; Alkhawaja, B. Determination of hydrolysis parameters of yohimbine HCl at neutral and slightly acidic medium. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 7, 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Nesmerak, K.; Lener, T.; Gubova, H.; Valaskova, L.; Sticha, M. Yohimbine stability: Analysis of its several decades-old pharmaceutical products and forced degradation study. Monatsh Chem. 2025, 156, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhum, A.A.H.; Mohamad, A.B.; Hammed, L.A.; Al-Amiery, A.A.; San, N.H.; Musa, A.Y. Inhibition of Mild Steel Corrosion in Hydrochloric Acid Solution by New Coumarin. Materials 2014, 7, 4335–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duca, D.-A.; Dan, M.L.; Vaszilcsin, N. Recycling of Expired Ceftamil Drug as Additive in the Copper and Nickel Electrodeposition from Acid Baths. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, M.L.; Rudenko, N.; Vaszilcsin, C.G.; Dima, G.-D. Sustainable Use of Expired Metoprolol as Corrosion Inhibitor for Carbon Steel in Saline Solution. Coatings 2025, 15, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.D.; Srivastava, A.; Tandon, P.; Jain, S. Molecular structure, vibrational spectra and HOMO, LUMO analysis of yohimbine hydrochloride by density functional theory and ab initio Hartree–Fock calculations. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 82, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, P.; De Proft, F.; Langenaeker, W. Conceptual Density Functional Theory. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1793–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, P.; De Proft, F. Chemical Reactivity as Described by Quantum Chemical Methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2002, 3, 276–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, H.; El Ashry, E.; El Nemr, A. Quantitative structure-activity relationships of some pyridine derivatives as corrosion inhibitors of steel in acidic medium. J. Mol. Model. 2012, 18, 1173–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenso, E.E.; Isabirye, D.A.; Eddy, N.O. Adsorption and Quantum Chemical Studies on the Inhibition Potentials of Some Thiosemicarbazides for the Corrosion of Mild Steel in Acidic Medium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2473–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, E.; Visser, P.; Mol, J.M.C.; Kosari, A.; Terryn, H.A.; Baert, K.; Gonzalez Garcia, Y. The effect of pH on the corrosion protection of aluminum alloys in lithium-carbonate-containing NaCl solutions. Corr. Sci. 2023, 210, 110851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-M. Role of Organic and Eco-Friendly Inhibitors on the Corrosion Mitigation of Steel in Acidic Environments—A State-of-Art Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhiba, F.; Lotfi, N.; Ourrak, K.; Benzekri, Z.; Zarrok, H.; Guenbour, A.; Boukhris, S.; Souizi, A.; El Hezzat, M.; Warad, I.; et al. Corrosion inhibition study of 2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-6-nitro-1,4-dihydroquinoxaline for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 3834–3843. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R.M.; Zaafarany, I.A. Kinetics of Corrosion Inhibition of Aluminum in Acidic Media by Water-Soluble Natural Polymeric Pectates as Anionic Polyelectrolyte Inhibitors. Materials 2013, 6, 2436–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaszilcsin, C.G.; Putz, M.V.; Kellenberger, A.; Dan, M.L. On the evaluation of metal-corrosion inhibitor interactions by adsorption isotherms. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1286, 135643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ituen, E.; Akaranta, O.; James, A.O. Evaluation of Performance of Corrosion Inhibitors Using Adsorption Isotherm Models: An Overview. Chem. Sci. Int. J. 2017, 18, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj, A. Corrosion inhibitors: Physisorbed or chemisorbed? Corros. Sci. 2021, 196, 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, F.; Mou, F.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Sim, L.B.; Chen, B. Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in Mixed HCl and H2SO4 Medium: A Study of 1,10-Phenanthroline Derivatives. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 24628–24641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azgaou, K.; Hisssou, R.; Chkirate, K.; Benmessaoud, M.; Hefnawy, M.; El Gamal, A.; Elmsellem, H.; Guo, L.; Essassi, E.M.; El Hajjaji, S.; et al. Corrosion Inhibition and Adsorption Properties of N-{2-[2-(5-Methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)acetamido]phenyl}benzamide Monohydrate on C38 Steel in 1 M HCl: Insights from Electrochemical Analysis, DFT, and MD Simulations. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 6244–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, H.H.; Reynoso, A.M.R.; Juan, C.; González, T.; Morán, C.O.G. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): A Review Study of Basic Aspects of the Corrosion Mechanism Applied to Steels. In Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu, S., Jr. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for the Measurement of the Corrosion Rate of Magnesium Alloys: Brief Review and Challenges. Metals 2020, 10, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Snihirova, D.; Havigh, M.D.; Deng, M.; Lamaka, S.V.; Terryn, H.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Non-stationarity in electrochemical impedance measurement of Mg-based materials in aqueous media. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 468, 143140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, D. Negative capacitance or inductive loop?–A general assessment of a common low frequency impedance feature. Electrochem. Commun. 2019, 98, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, D.A.; Dan, M.L.; Vaszilcsin, N. Expired domestic drug—Paracetamol—As corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in acid media. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 416, 012118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberger, A.; Duca, D.A.; Dan, M.L.; Medeleanu, M. Recycling unused midazolam drug as efficient corrosion inhibitor for copper in nitric acid solution. Materials 2022, 15, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Peng, X.; Bai, X.; Chen, Z.; Xie, R.; He, B.; Han, P. EIS analysis of the electrochemical characteristics of the metal–water interface under the effect of temperature. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16979–16990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, M.; Ramezani, F.; Elyasi, M.; Sadeghi-Aliabadi, H.; Amanlou, M. A; study on quantitative structure–activity relationship and molecular docking of metalloproteinase inhibitors based on L-tyrosine scaffold. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengatesh, G.; Sundaravadivelu, M. Quantum chemical, experimental, theoretical spectral (FT-IR and NMR) studies and molecular docking investigation of 4,8,9,10-tetraaryl-1,3-diazaadamantan-6-ones. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 4395–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh Khabazi, M.; Najafi Chermahini, A. DFT Study on Corrosion Inhibition by Tetrazole Derivatives: Investigation of the Substitution Effect. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 9978–9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamiery, A.A.; Wan Isahak, W.N.R.; Takriff, M.S. Inhibition of Mild Steel Corrosion by 4-benzyl-1-(4-oxo-4-phenylbutanoyl)thiosemicarbazide: Gravimetrical, Adsorption and Theoretical Studies. Lubricants 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, S.; Foroughi, M.M.; Dehdab, M.; Shahidi Zandi, M. Computational evaluation of corrosion inhibition of four quinoline derivatives on carbon steel in aqueous phase. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2019, 38, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

| Fe (%) | C (%) | P (%) | S (%) | Mn (%) | Si (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97.60 | 0.20 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 1.60 | 0.050 |

| Metal | T [K] | YHB conc. | icorr | Ecorr | -bc | ba | vcorr | IE | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [μA cm−2] | [mV] | [mV dec−1] | [mV dec−1] | [mm y−1] | [%] | ||||

| OLC52 | 298 | BS | 764.4 ± 15.27 | −635.6 ± 2.01 | 286.3 ± 5.31 | 236.2 ± 3.0 | 8.89 ± 0.180 | - | - |

| 10−6 M | 637. ± 7.91 | −633.0 ± 1.14 | 237.8 ± 9.8 | 223.4 ± 8.5 | 7.41 ± 0.092 | 16.6 | 0.17 | ||

| 10−5 M | 576.6 ± 1.69 | −625.1 ± 2.56 | 200.1 ± 6.6 | 150.3 ± 4.9 | 6.71 ± 0.021 | 24.6 | 0.25 | ||

| 10−4 M | 256.9 ± 2.90 | −619.4 ± 2.08 | 194.1 ± 4.1 | 148.2 ± 3.0 | 2.99 ± 0.339 | 66.4 | 0.66 | ||

| 2.5∙ 10−4 M | 198.8 ± 19.4 | −621.4 ± 1.29 | 171.9 ± 10.3 | 125.8 ± 4.4 | 2.31 ± 0.226 | 74.0 | 0.74 | ||

| 5∙ 10−4 M | 38.2 ± 3.18 | −618.4 ± 3.18 | 15.4 ± 1.7 | 12.1 ± 2.2 | 0.44 ± 0.039 | 95.0 | 0.95 | ||

| 308 | BS | 837.6 ± 33.71 | −640.1 ± 0.96 | 295.4 ± 14.3 | 239.3 ± 0.6 | 9.74 ± 0.388 | - | - | |

| 10−6 M | 644.3 ± 34.69 | −633.8 ± 1.98 | 270.3 ± 13.8 | 237.5 ± 2.6 | 7.49 ± 0.391 | 23.1 | 0.23 | ||

| 10−5 M | 617.6 ± 25.68 | −625.5 ± 2.94 | 203.8 ± 2.8 | 154.9 ± 2.3 | 7.18 ± 0.297 | 26.3 | 0.26 | ||

| 10−4 M | 265.7 ± 8.80 | −618.9 ± 0.34 | 203.3 ± 19.7 | 145.5 ± 2.6 | 2.49 ± 0.246 | 68.3 | 0.68 | ||

| 2.5 ∙ 10−4 M | 193.0 ± 16.45 | −621.7 ± 1.67 | 198.9 ± 6.4 | 140.7 ± 5.6 | 2.24 ± 0.193 | 77.0 | 0.77 | ||

| 5 ∙ 10−4 M | 45.9 ± 0.96 | −609.2 ± 2.54 | 24.6 ± 0.7 | 17.7 ± 1.4 | 0.53 ± 0.011 | 94.5 | 0.95 | ||

| 318 | BS | 1307.8 ± 12.16 | −637.1 ± 1.08 | 273.9 ± 1.6 | 230.7 ± 4.3 | 15.20 ± 0.146 | - | - | |

| 10−6 M | 781.4 ± 4.97 | −631.8 ± 0.73 | 251.3 ± 7.3 | 298.7 ± 4.0 | 9.08 ± 0.053 | 40.2 | 0.40 | ||

| 10−5 M | 651.9 ± 35.30 | −632.5 ± 1.66 | 277.5 ± 0.9 | 228.3 ± 0.5 | 7.58 ± 0.326 | 50.2 | 0.50 | ||

| 10−4 M | 273.5 ± 8.27 | −621.6 ± 2.21 | 256.1 ± 2.9 | 191.9 ± 3.7 | 3.18 ± 0.096 | 79.1 | 0.79 | ||

| 2.5 ∙ 10−4M | 240.8 ± 8.40 | −619.9 ± 1.96 | 210.1 ± 1.5 | 140.9 ± 5.9 | 2.80 ± 0.100 | 81.6 | 0.82 | ||

| 5 ∙ 10−4 M | 65.9 ± 4.99 | −612.9 ± 0.12 | 25.5 ± 1.2 | 25.7 ± 1.0 | 0.77 ± 0.056 | 95.0 | 0.95 | ||

| 328 | BS | 1349.8 ± 8.04 | −636.8 ± 1.73 | 276.5 ± 10.3 | 254.4 ± 14.6 | 15.70 ± 0.050 | - | - | |

| 10−6 M | 1172.3 ± 27.24 | −637.6 ± 1.53 | 225.6 ± 3.3 | 196.8 ± 6.0 | 13.63 ± 0.316 | 13.2 | 0.13 | ||

| 10−5 M | 792.5 ± 14.93 | −628.9 ± 1.72 | 213.6 ± 2.3 | 180.6 ± 3.0 | 9.22 ± 0.174 | 41.3 | 0.41 | ||

| 10−4 M | 460.3 ± 22.17 | −625.8 ± 1.10 | 158 ± 6.1 | 133.9 ± 4.5 | 5.35 ± 0.259 | 65.9 | 0.66 | ||

| 2.5∙ 10−4 M | 241.9 ± 2.92 | −618.7 ± 2.28 | 188.7 ± 4.3 | 127.4 ± 1.5 | 2.81 ± 0.034 | 82.1 | 0.82 | ||

| 5∙ 10−4 M | 67.7 ± 10.13 | −614.3 ± 1.73 | 27.6 ± 4.3 | 23.9 ± 2.0 | 0.79 ± 0.117 | 95.0 | 0.95 |

| Metal | T [K] | YHB conc. | icorr | Ecorr | -bc | ba | vcorr | IE | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [μA cm−2] | [mV] | [mV dec−1] | [mV dec−1] | [mm y−1] | [%] | ||||

| Al | 298 | BS | 32.9 ± 0.60 | −556 ± 3.83 | 534.9 ± 6.10 | 649 ± 5.30 | 0.358 ± 0.007 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| 10−6 M | 19.9 ± 0.44 | −549 ± 2.90 | 328.5 ± 5.30 | 364.8 ± 3.50 | 0.217 ± 0.005 | 39.3 | 0.39 | ||

| 10−5 M | 13.5 ± 0.66 | −546 ± 1.53 | 173.2 ± 1.20 | 292.5 ± 6.30 | 0.146 ± 0.008 | 59.0 | 0.59 | ||

| 10−4 M | 6.2 ± 0.21 | −526 ± 1.29 | 169.5 ± 2.80 | 205.7 ± 5.50 | 0.067 ± 0.002 | 81.2 | 0.81 | ||

| 2.5∙ 10−4 M | 4.3 ± 0.51 | −493 ± 1.20 | 123.8 ± 4.20 | 127.1 ± 1.30 | 0.047 ± 0.005 | 86.9 | 0.87 | ||

| 5∙ 10−4 M | 2.8 ± 0.17 | −410 ± 0.88 | 47 ± 1.10 | 52.3 ± 2.70 | 0.03 ± 0.002 | 91.5 | 0.91 | ||

| 308 | BS | 33.7 ± 3.06 | −561 ± 3.02 | 554 ± 3.00 | 704 ± 17.3 | 0.367 ± 0.033 | 0.0 | 0.00 | |

| 10−6 M | 21.9 ± 0.48 | −550 ± 3.54 | 337 ± 1.90 | 392 ± 5.50 | 0.238 ± 0.005 | 35.0 | 0.35 | ||

| 10−5 M | 13.5 ± 0.95 | −551 ± 3.39 | 503 ± 4.10 | 404.2 ± 10.5 | 0.147 ± 0.010 | 59.9 | 0.60 | ||

| 10−4 M | 7.6 ± 0.04 | −510 ± 2.00 | 276 ± 0.80 | 238 ± 3.40 | 0.082 ± 0.001 | 77.6 | 0.78 | ||

| 2.5∙ 10−4 M | 5.4 ± 0.41 | −509 ± 2.25 | 145 ± 1.00 | 129 ± 1.80 | 0.059 ± 0.005 | 83.9 | 0.84 | ||

| 5∙ 10−4 M | 3.0 ± 0.03 | −447 ± 1.79 | 72.7 ± 6.90 | 68.2 ± 3.10 | 0.033 ± 0.001 | 91.0 | 0.91 | ||

| 318 | BS | 33.8 ± 0.73 | −567 ± 3.51 | 598 ± 2.90 | 641 ± 3.00 | 0.368 ± 0.008 | 0.0 | 0.00 | |

| 10−6 M | 24.5 ± 0.11 | −546 ± 1.00 | 379 ± 6.30 | 452 ± 2.80 | 0.267 ± 0.001 | 27.5 | 0.28 | ||

| 10−5 M | 17.0 ± 0.12 | −546 ± 1.84 | 269.8 ± 2.10 | 311 ± 4.70 | 0.225 ± 0.024 | 49.7 | 0.50 | ||

| 10−4 M | 9.8 ± 0.72 | −522 ± 1.39 | 116.7 ± 1.76 | 94.5 ± 0.30 | 0.106 ± 0.008 | 71.1 | 0.71 | ||

| 2.5∙ 10−4 M | 6.5 ± 0.27 | −501 ± 1.25 | 74 ± 3.70 | 93 ± 4.50 | 0.071 ± 0.003 | 80.7 | 0.81 | ||

| 5∙ 10−4 M | 5.0 ± 0.13 | −488 ± 2.00 | 73.5 ± 2.40 | 68.4 ± 2.00 | 0.054 ± 0.002 | 85.2 | 0.85 | ||

| 328 | BS | 34.4 ± 0.95 | −570 ± 2.89 | 557 ± 9.00 | 718 ± 2.10 | 0.375 ± 0.010 | 0.0 | 0.00 | |

| 10−6 M | 25.4 ± 0.46 | −517 ± 1.13 | 383.1 ± 5.30 | 501.5 ± 2.7 | 0.277 ± 0.005 | 26.1 | 0.26 | ||

| 10−5 M | 17.1 ± 0.91 | −552 ± 2.91 | 337 ± 2.40 | 280 ± 5.20 | 0.186 ± 0.010 | 50.4 | 0.50 | ||

| 10−4 M | 11.0 ± 0.40 | −524 ± 0.46 | 126 ± 6.00 | 179 ± 4.60 | 0.12 ± 0.005 | 68.0 | 0.68 | ||

| 2.5∙ 10−4 M | 7.5 ± 0.69 | −515 ± 2.22 | 126 ± 2.40 | 176 ± 1.10 | 0.081 ± 0.008 | 78.2 | 0.78 | ||

| 5 ∙ 10−4 M | 5.7 ± 0.04 | −491 ± 1.65 | 93.3 ± 1.20 | 97.3 ± 0.40 | 0.062 ± 0.001 | 83.4 | 0.83 |

| Electrode | Solution | Ea [kJ mol−1] | ΔHa [kJ mol−1] | ΔSa [J mol−1 K−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLC52 | BS (blank) | 17.50 | 14.906 | −139.97 |

| BS + 5∙ 10−4 mol L−1 YHB | 16.99 | 14.394 | −166.31 |

| Electrode | Solution | Ea [kJ mol−1] | ΔHa [kJ mol−1] | ΔSa [J mol−1 K−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | BS (blank) | 1.16 | −1.44 | −220.71 |

| BS + 5 ∙ 10−4 mol L−1 YHB | 21.30 | 18.70 | −174.10 |

| Electrode | T [K] | Kads | [kJ mol−1] | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLC52 | 298 | 2.92∙ 104 | −35.43 | 0.990 | 2.72 ∙ 10−5 |

| 308 | 3.38∙ 104 | −36.99 | 0.993 | 2.25 ∙ 10−5 | |

| 318 | 6.68∙ 104 | −39.99 | 0.996 | 1.59 ∙ 10−5 | |

| 328 | 3.99∙ 104 | −39.85 | 0.996 | 1.84∙ 10−5 | |

| Al | 298 | 1.22∙ 105 | −38.96 | 0.999 | 6.12 ∙ 10−6 |

| 308 | 9.35∙ 104 | −39.60 | 0.998 | 9.20 ∙ 10−6 | |

| 318 | 8.09∙ 104 | −40.50 | 0.998 | 8.09 ∙ 10−6 | |

| 328 | 7.35 ∙ 104 | −41.51 | 0.998 | 1.03 ∙ 10−5 |

| Metal | YHB Concentration | EOCP | Eox | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mv/EOCP | 250 mv/EOCP | |||

| icorr | ||||

| [mV]/Ref | [A m−2] | |||

| OLC52 | BS | −635 | 4.2 | 48 |

| 10−6 M | −633 | 3.8 | 47 | |

| 10−5 M | −625 | 3.5 | 44 | |

| 10−4 M | −621 | 3.2 | 42 | |

| 2.5 ∙ 10−4 M | −619 | 2.9 | 37 | |

| 5 ∙ 10−4 M | −618 | 2.4 | 32 | |

| Al | BS | −560 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| 10−6 M | −535 | 0.55 | 0.9 | |

| 10−5 M | −515 | 0.42 | 0.8 | |

| 10−4 M | −502 | 0.4 | 0.75 | |

| 2.5 ∙ 10−4 M | −482 | 0.25 | 0.4 | |

| 5 ∙ 10−4 M | −419 | 0.1 | 0.15 | |

| YHB Conc. (M) | RS (Ω) | CPE-T (F cm−2 sn−1) · 103 | n | Rct (Ω cm2) | χ2 | L (H cm2) | RL (Ω cm2) | Cdl·104 (µF cm−2) | E (%) | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | 1.85 (0.17%) | 1.73 (2.51%) | 0.73 (1.10%) | 19.42 (0.69%) | 0.56 × 10−3 | 1.07 (2.83) | 7.831 (5.13) | 2.08 | – | – |

| 10−6 | 1.65 (0.28%) | 2.55 (3.78%) | 0.66 (1.13%) | 29.17 (0.71%) | 1.99 × 10−3 | 2.38 (1.19) | 4.548 (0.89) | 1.50 | 33.4 | 0.33 |

| 10−5 | 1.90 (0.17%) | 2.93 (2.32%) | 0.64 (0.74%) | 40.49 (0.71%) | 0.41 × 10−3 | 2.81 (0.83) | 7.775 (0.65) | 1.63 | 52.0 | 0.52 |

| 10−4 | 1.58 (0.35%) | 3.00 (2.55%) | 0.64 (0.93%) | 61.36 (0.69%) | 2.03 × 10−3 | 20.9 (0.87) | 13.22 (0.67) | 1.50 | 68.4 | 0.68 |

| 2.5∙ 10−4 | 1.98 (0.43%) | 3.12 (3.04%) | 0.63 (1.00%) | 91.58 (1.00%) | 1.91 × 10−3 | 16.5 (0.99) | 25.29 (0.94) | 1.67 | 78.8 | 0.79 |

| 5 ∙ 10−4 | 2.36 (0.59%) | 3.21 (3.22%) | 0.61 (1.15%) | 169.8 (0.97%) | 3.93 × 10−3 | 49.2 (0.82) | 51.29 (0.95) | 1.51 | 88.6 | 0.87 |

| T (K) | RS (Ω) | CPE-T (F cm−2 sn−1) · 103 | n | Rct (Ω cm2) | χ2 | L (L cm2) | RL (Ω cm2) | Cdl·104 (µF cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 2.19 (0.55%) | 2.05 (3.51%) | 0.65 (1.21%) | 107.7 (1.16%) | 3.88 × 10−3 | 26.85 (1.25) | 31.05 (1.08) | 1.11 |

| 308 | 1.98 (0.43%) | 3.12 (3.04%) | 0.63 (1.03%) | 91.58 (1.00%) | 1.91 × 10−3 | 16.5 (0.99) | 25.29 (0.94) | 1.67 |

| 318 | 1.58 (0.56%) | 3.25 (3.22%) | 0.57 (0.27%) | 79.18 (1.11%) | 1.13 × 10−3 | 18.44 (0.77) | 26.79 (0.80) | 0.84 |

| 328 | 1.18 (0.51%) | 3.42 (3.35%) | 0.52 (1.12%) | 75.42 (1.32%) | 0.87 × 10−3 | 7.36 (1.44) | 14.26 (0.96) | 0.83 |

| YHB Conc. (M) | RS (Ω) | CPE-T (F cm−2 sn−1) · 105 | n | Rct (Ω cm2) | χ2 | L (L cm2) | RL (Ω cm2) | Cdl·106 (µF cm−2) | E (%) | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | 2.79 (0.46%) | 2.63 (1.48%) | 0.84 (0.26%) | 1044 (0.90%) | 2.04 × 10−3 | 100.7 (2.34) | 141 (1.01) | 4.47 | – | – |

| 10−6 | 2.05 (0.43%) | 2.57 (1.25%) | 0.83 (0.22%) | 1700 (0.94%) | 1.28 × 10−3 | 525.6 (3.47) | 307 (1.66) | 4.03 | 38.6 | 0.39 |

| 10−5 | 4.17 (0.54%) | 2.53 (1.53%) | 0.83 (0.28%) | 2518 (0.93%) | 2.08 × 10−3 | 973.5 (4.78) | 638 (2.19) | 3.68 | 58.5 | 0.59 |

| 10−4 | 4.68 (0.70%) | 2.47 (1.74%) | 0.82 (0.32%) | 3629 (1.01%) | 3.48 × 10−3 | 1449 (0.49) | 1037 (0.41) | 3.31 | 71.2 | 0.71 |

| 2.5∙ 10−4 | 4.46 (1.09%) | 2.38 (2.00%) | 0.79 (0.43%) | 4962 (1.09%) | 5.27 × 10−3 | 1651 (0.68) | 1149 (0.64) | 3.04 | 79.0 | 0.79 |

| 5 ∙ 10−4 | 3.36 (0.77%) | 2.26 (1.58%) | 0.78 (0.31%) | 7314 (1.09%) | 4.38 × 10−3 | 2148 (1.46) | 1387 (0.77) | 2.72 | 87.7 | 0.88 |

| T (K) | RS (Ω) | CPE-T (F cm−2 sn−1) · 103 | n | Rct (Ω cm2) | χ2 | L (L cm2) | RL (Ω cm2) | Cdl·104 (µF cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 6.47 (0.70%) | 2.11 (1.60%) | 0.82 (0.31%) | 5291 (1.12%) | 3.34 × 10−3 | 3499 (2.04) | 2093 (3.11) | 4.03 |

| 308 | 4.46 (1.09%) | 2.38 (2.00%) | 0.79 (0.43%) | 4962 (1.09%) | 5.27 × 10−3 | 1651 (2.81) | 1649 (4.38) | 3.04 |

| 318 | 1.25 (0.67%) | 2.97 (1.55%) | 0.78 (0.29%) | 4465 (0.83%) | 3.41 × 10−3 | 470 (2.42) | 974 (2.65) | 2.47 |

| 328 | 7.39 (0.39%) | 3.93 (0.99%) | 0.76 (0.20%) | 4228 (0.46%) | 1.05 × 10−3 | 371 (1.02) | 669 (2.54) | 1.97 |

| Molecular Descriptor | Value |

|---|---|

| EHOMO (eV) | −8.38 |

| ELUMO (eV) | −0.60 |

| ΔE (eV) | 7.78 |

| µ (Debye) | 2.84 |

| χ (eV) | 3.89 |

| η (eV) | 4.49 |

| σ (eV−1) | 0.22 |

| V [Å3] | 994.73 |

| S [Å2] | 581.72 |

| V/S [Å] | 1.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dima, G.-D.; Dan, M.L.; Rudenko, N.; Vaszilcsin, N. Evaluation of the Inhibitory Efficiency of Yohimbine on Corrosion of OLC52 Carbon Steel and Aluminum in Acidic Acetic/Acetate Media. Coatings 2025, 15, 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121458

Dima G-D, Dan ML, Rudenko N, Vaszilcsin N. Evaluation of the Inhibitory Efficiency of Yohimbine on Corrosion of OLC52 Carbon Steel and Aluminum in Acidic Acetic/Acetate Media. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121458

Chicago/Turabian StyleDima, George-Daniel, Mircea Laurențiu Dan, Nataliia Rudenko, and Nicolae Vaszilcsin. 2025. "Evaluation of the Inhibitory Efficiency of Yohimbine on Corrosion of OLC52 Carbon Steel and Aluminum in Acidic Acetic/Acetate Media" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121458

APA StyleDima, G.-D., Dan, M. L., Rudenko, N., & Vaszilcsin, N. (2025). Evaluation of the Inhibitory Efficiency of Yohimbine on Corrosion of OLC52 Carbon Steel and Aluminum in Acidic Acetic/Acetate Media. Coatings, 15(12), 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121458