In Situ Neutron and Synchrotron X-Ray Analysis of Structural Evolution on Plastically Deformed Metals During Annealing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Comparison Between Neutron and Synchrotron X-Ray Diffraction

3. In Situ Neutron Studies on Plastically Deformed Bulk Metals upon Heating

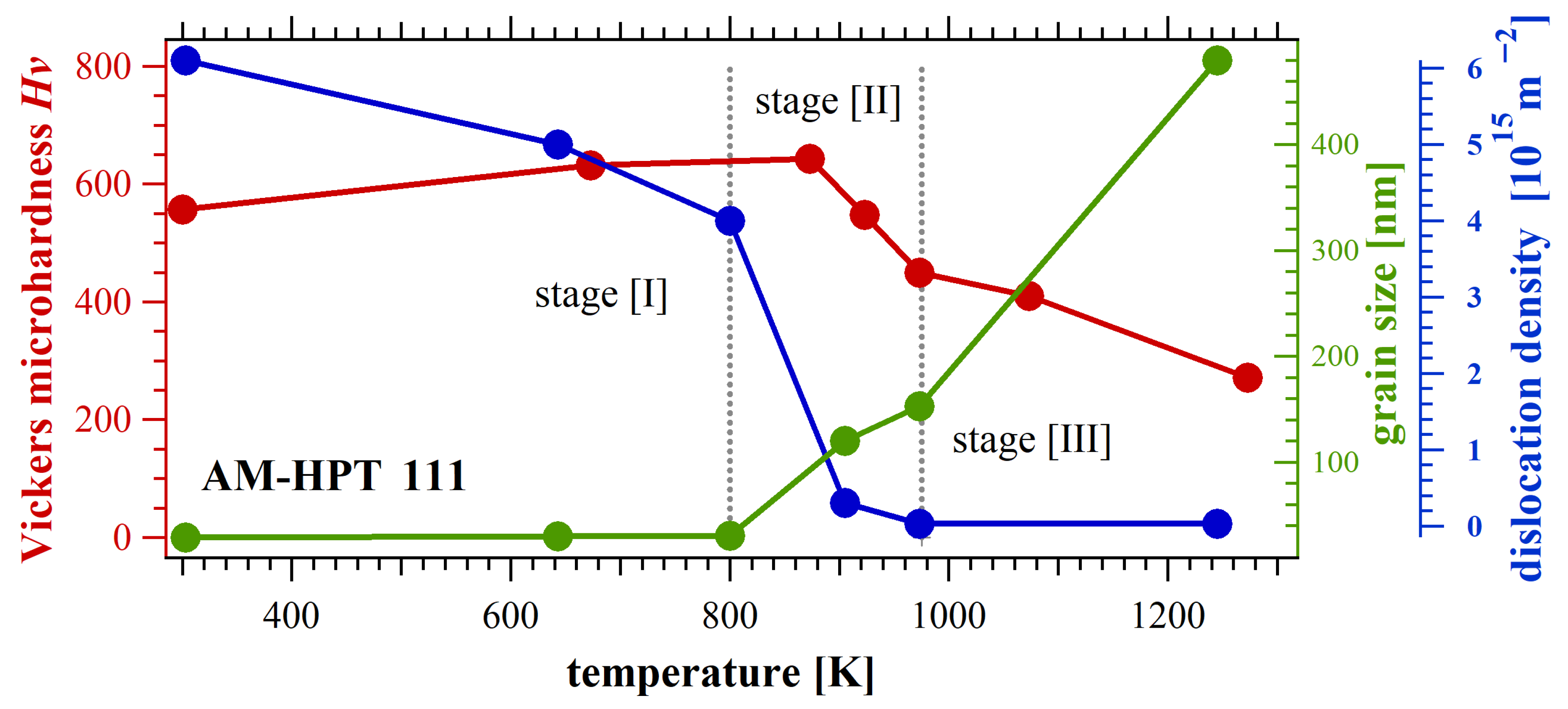

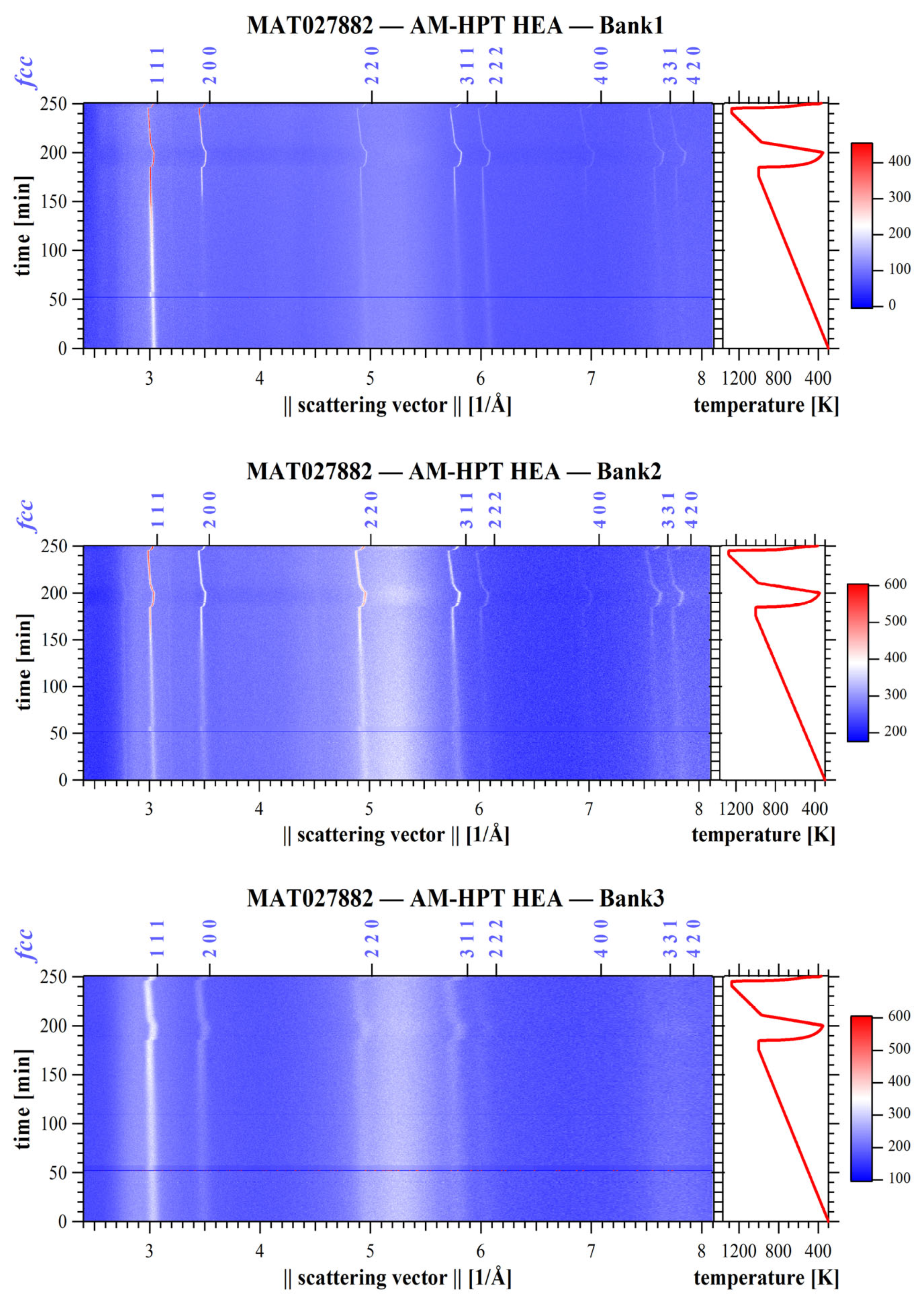

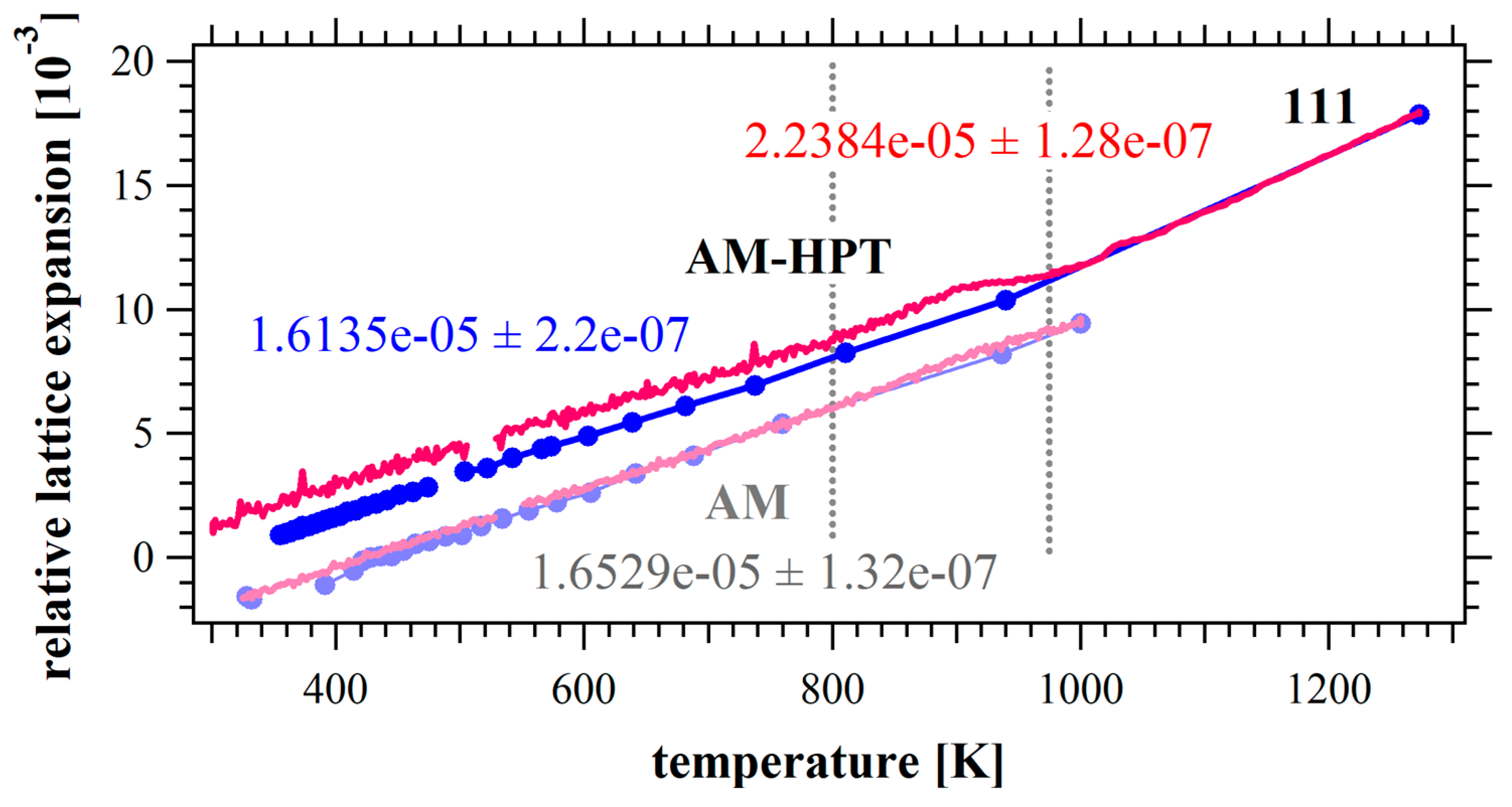

3.1. CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys

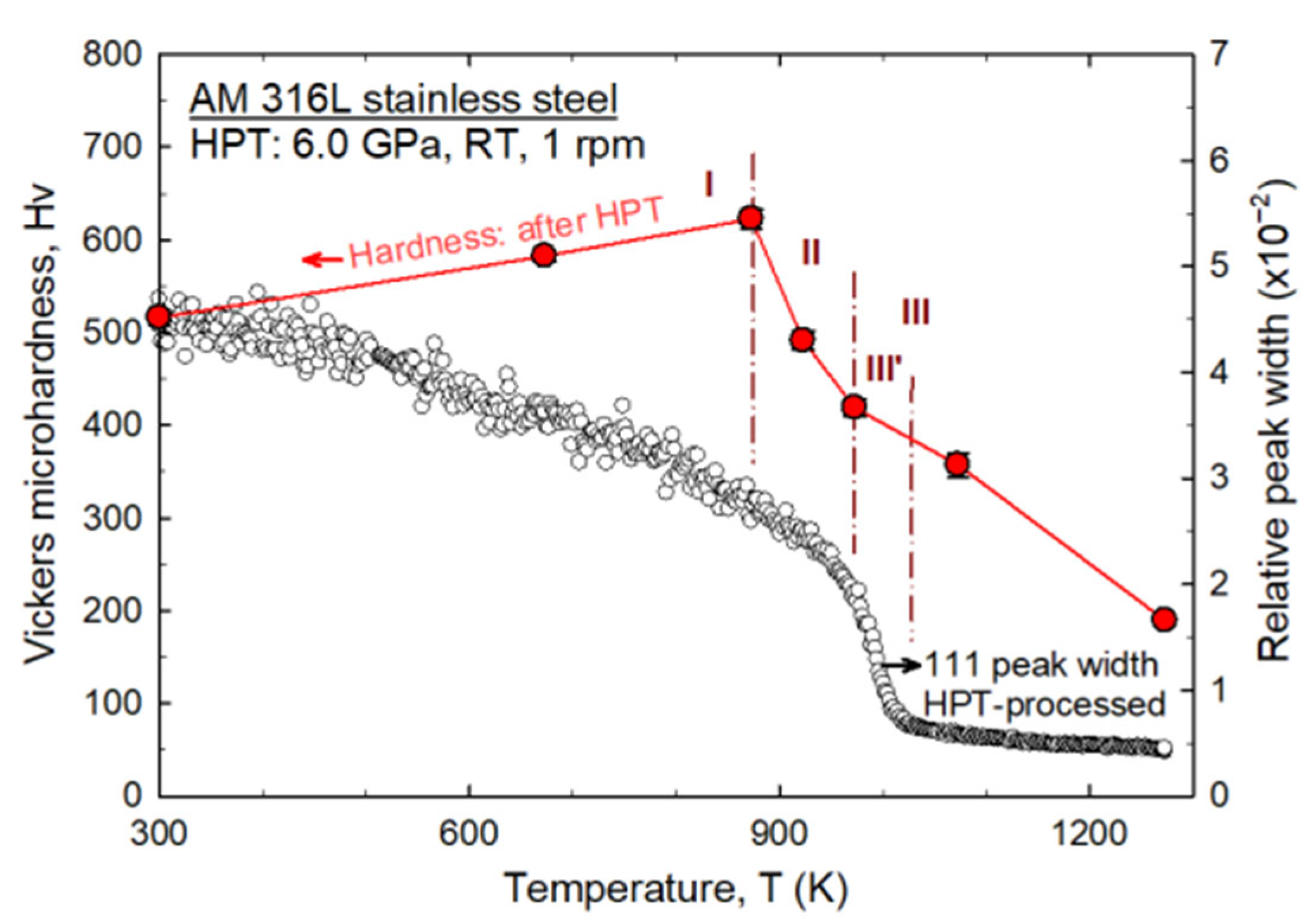

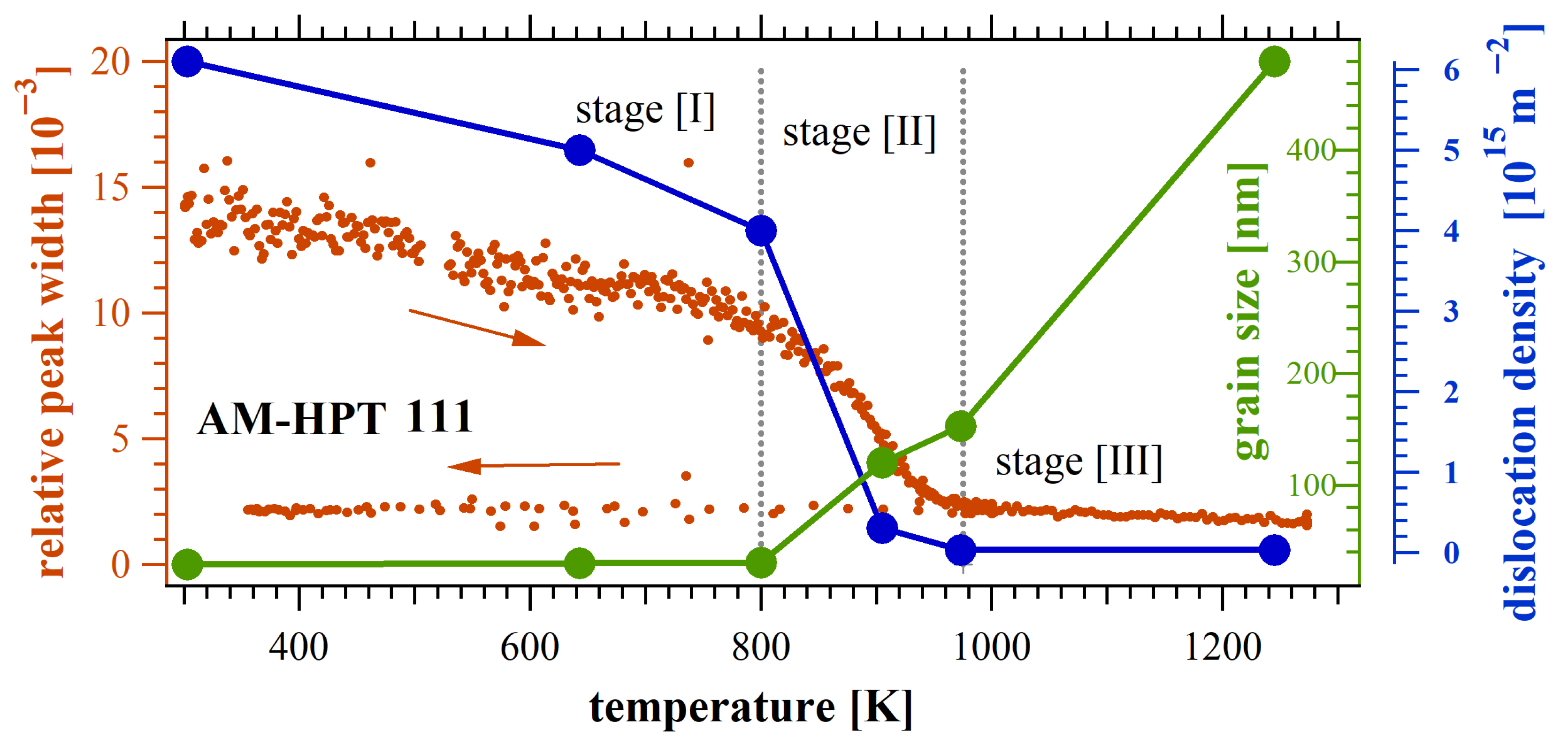

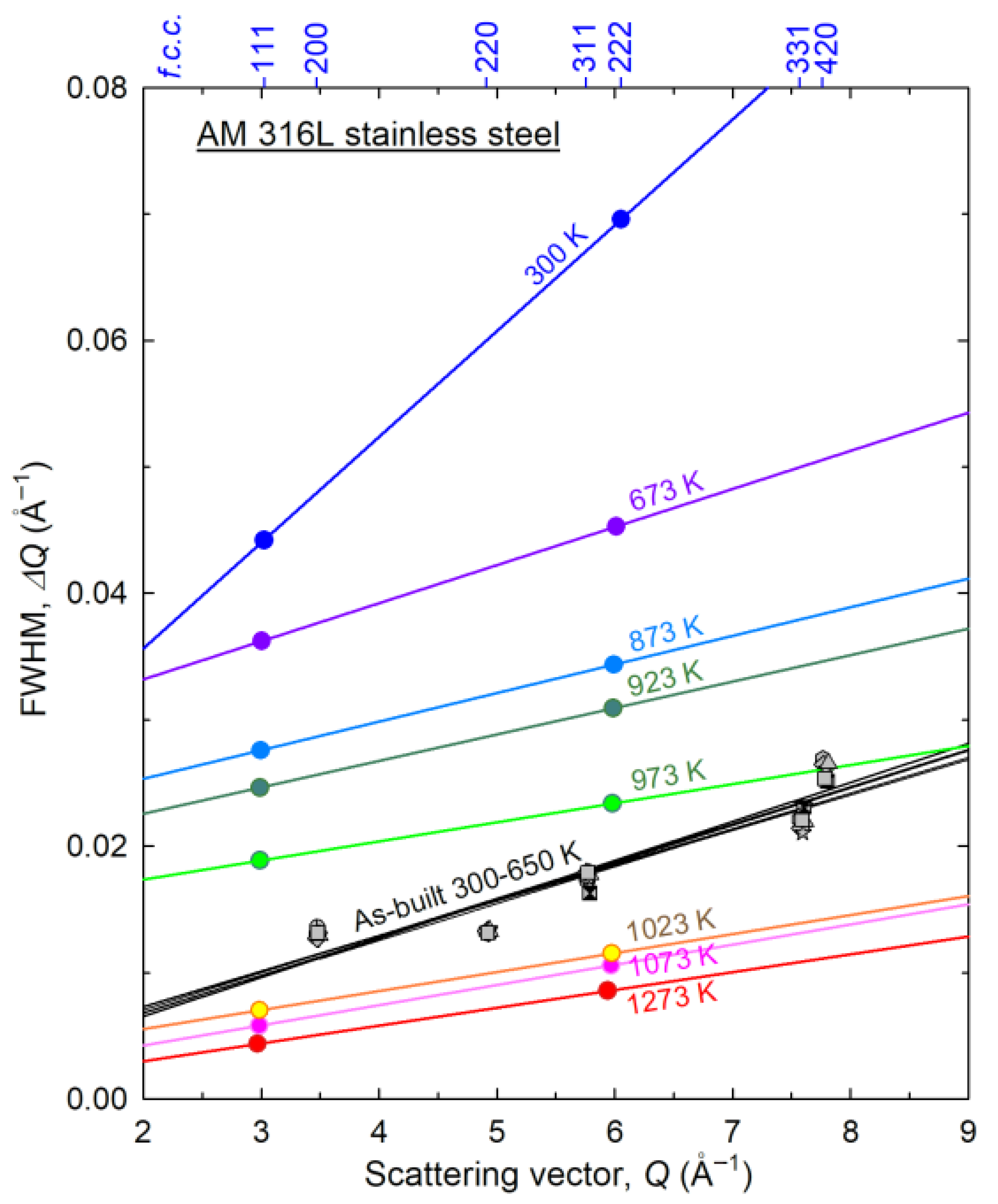

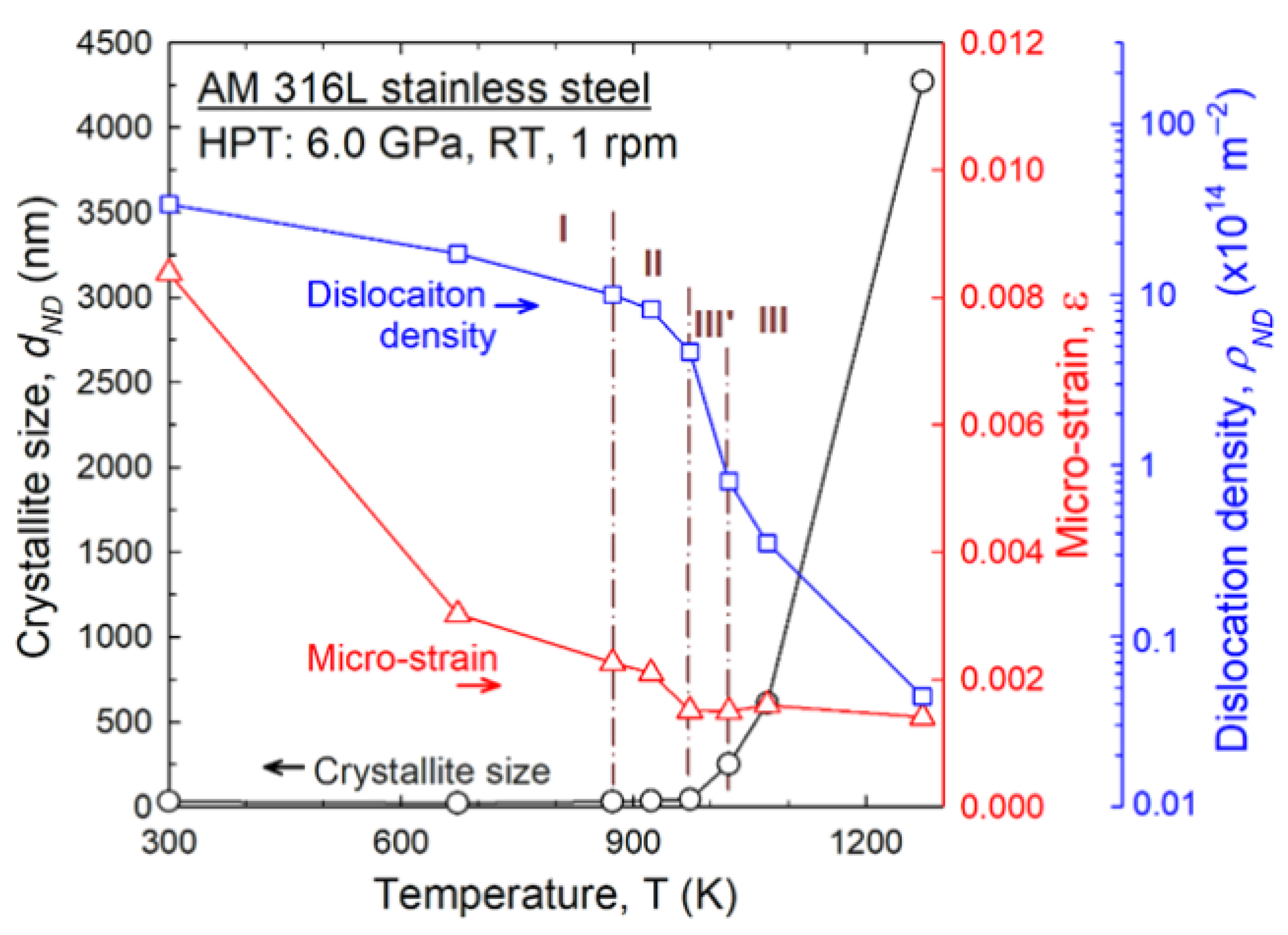

3.2. 316L Stainless Steels

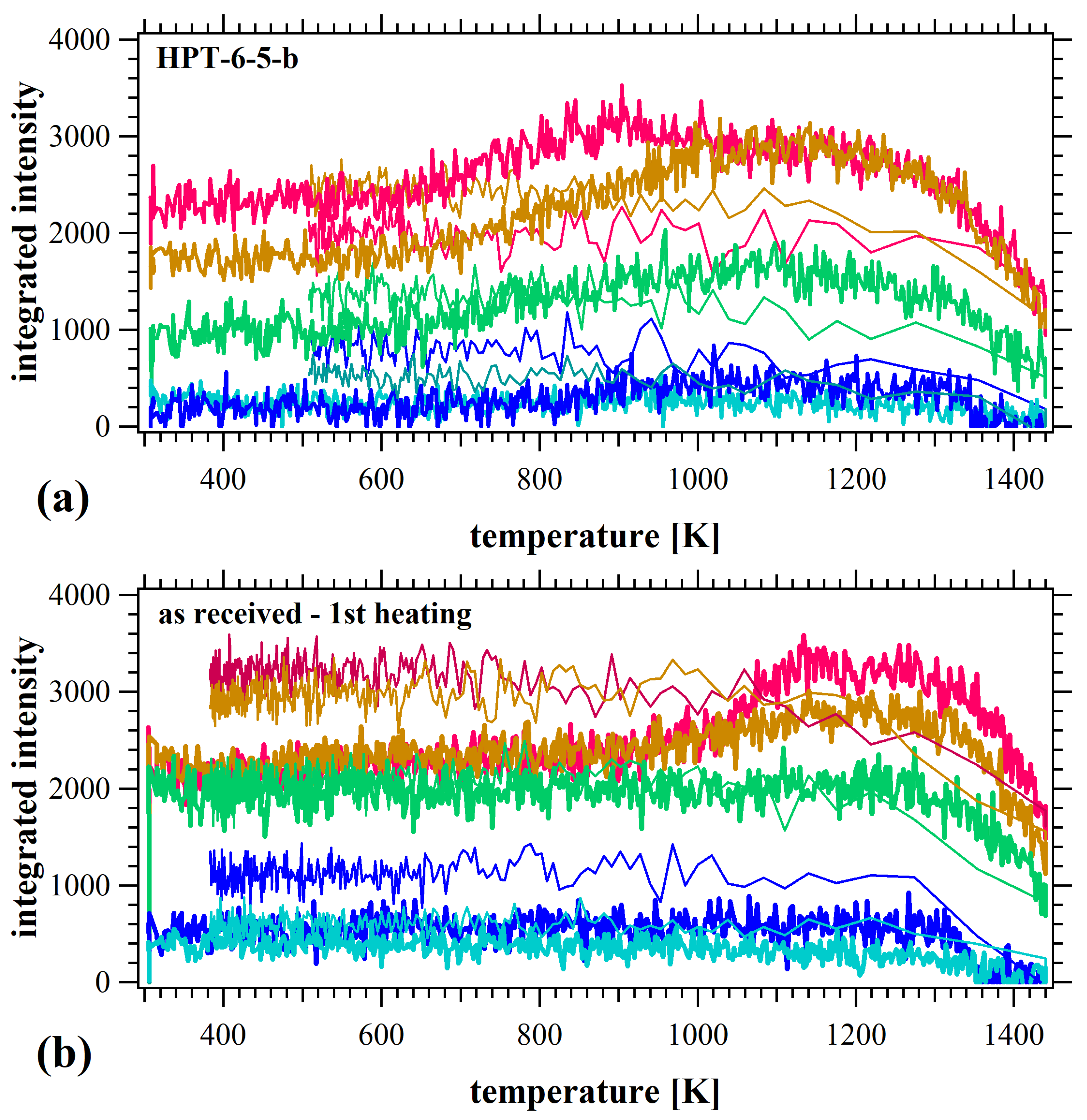

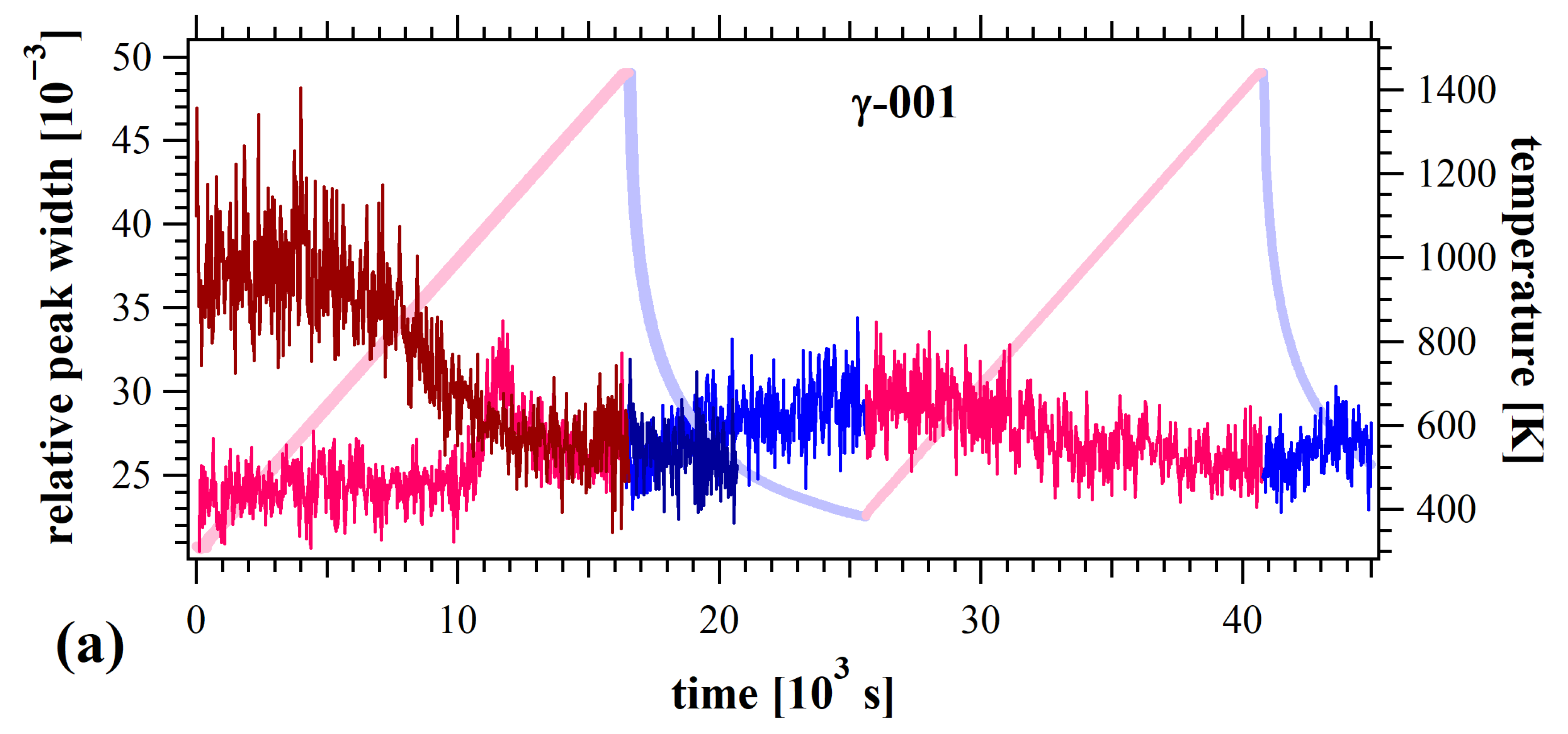

3.3. TiAl Alloys

4. In Situ Synchrotron X-Ray Analysis on Plastically Deformed Bulk Metals upon Heating

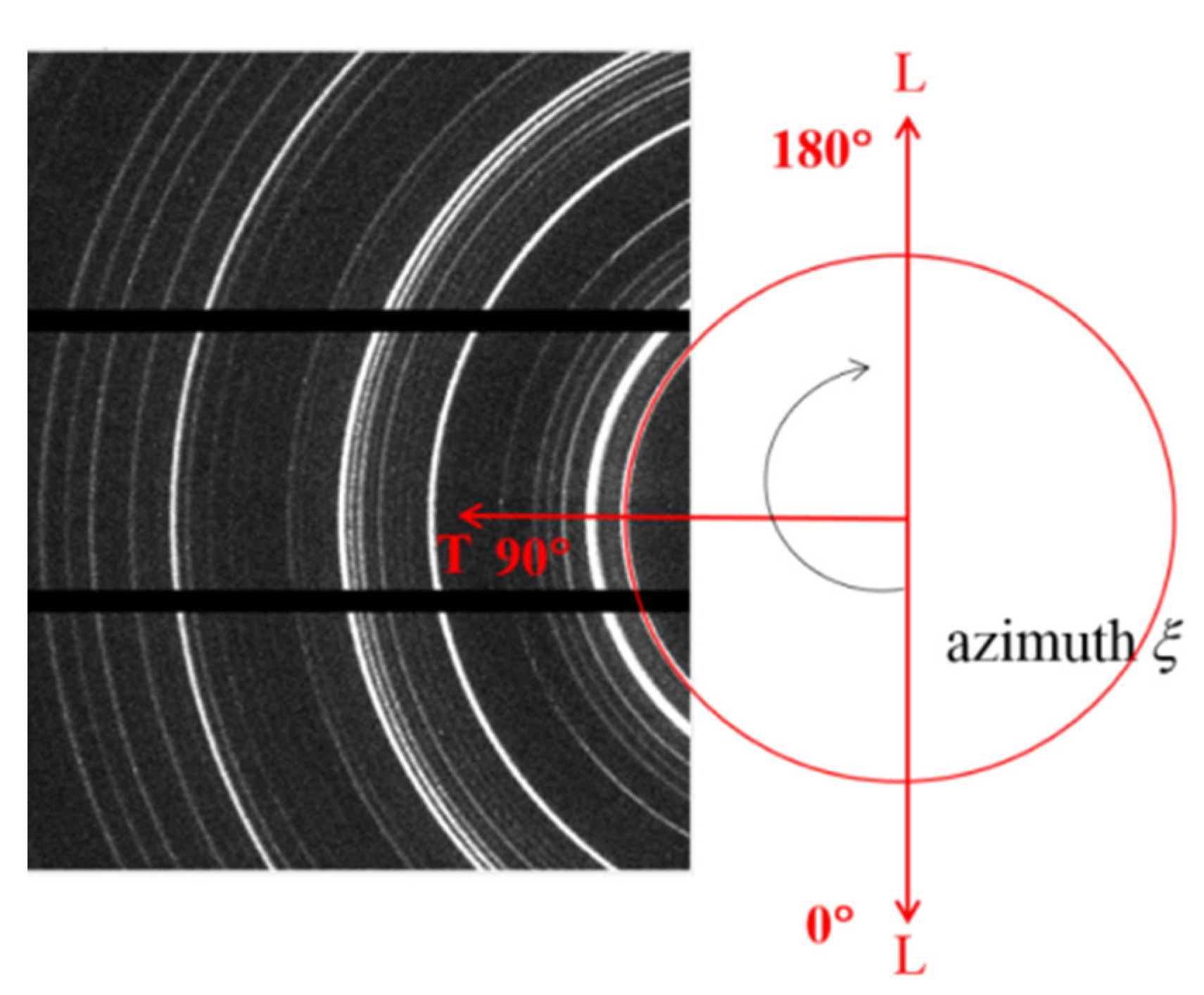

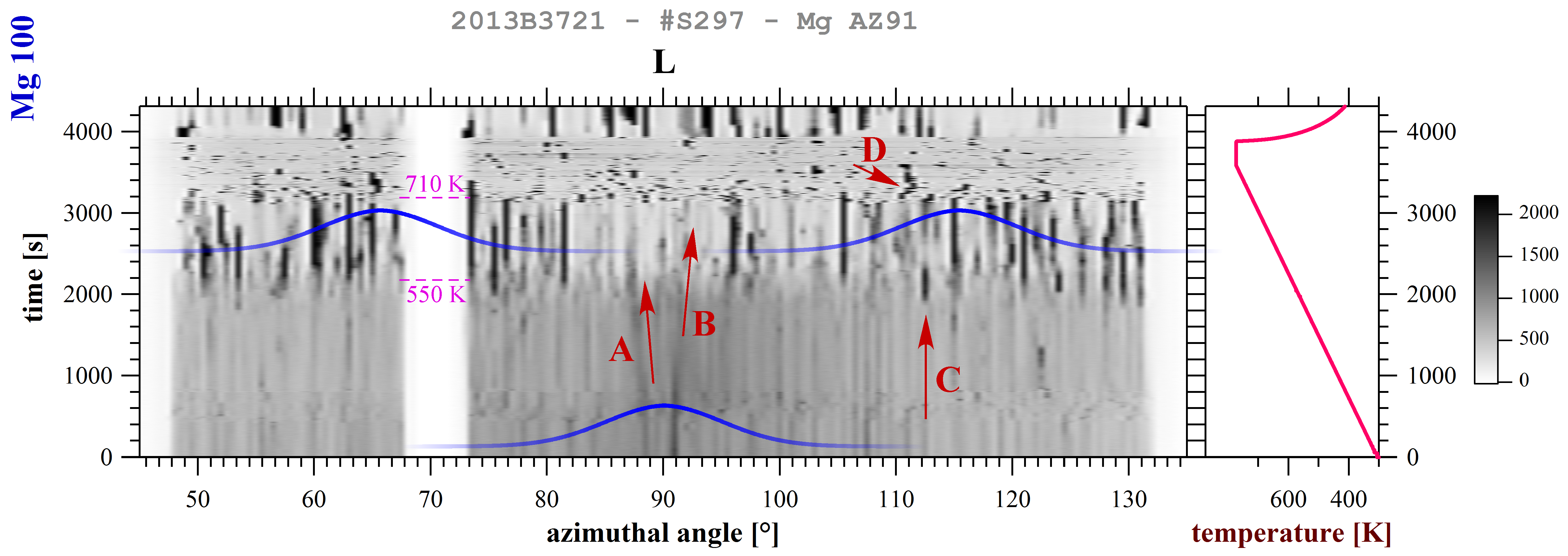

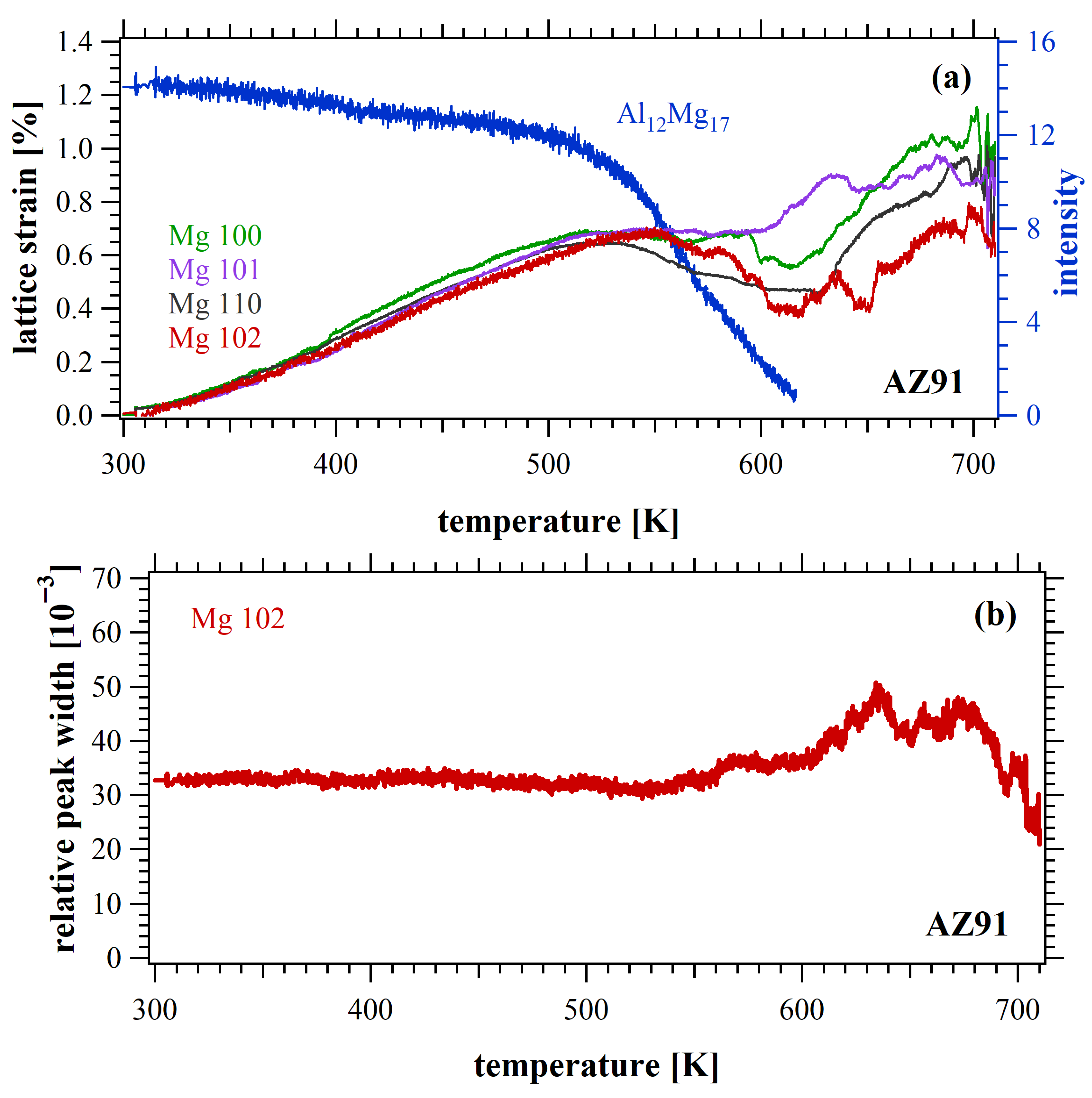

4.1. Mg-Al Alloys

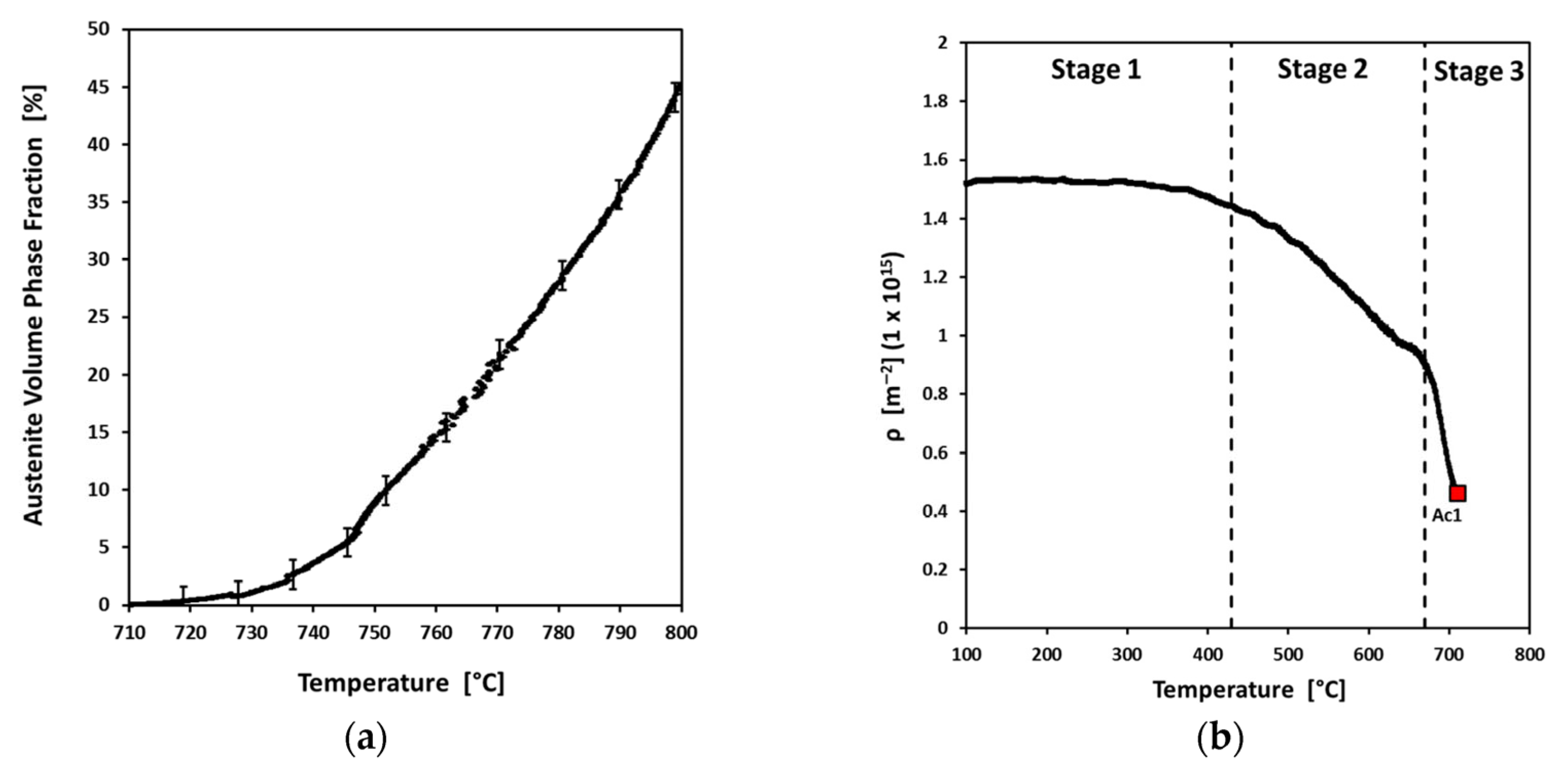

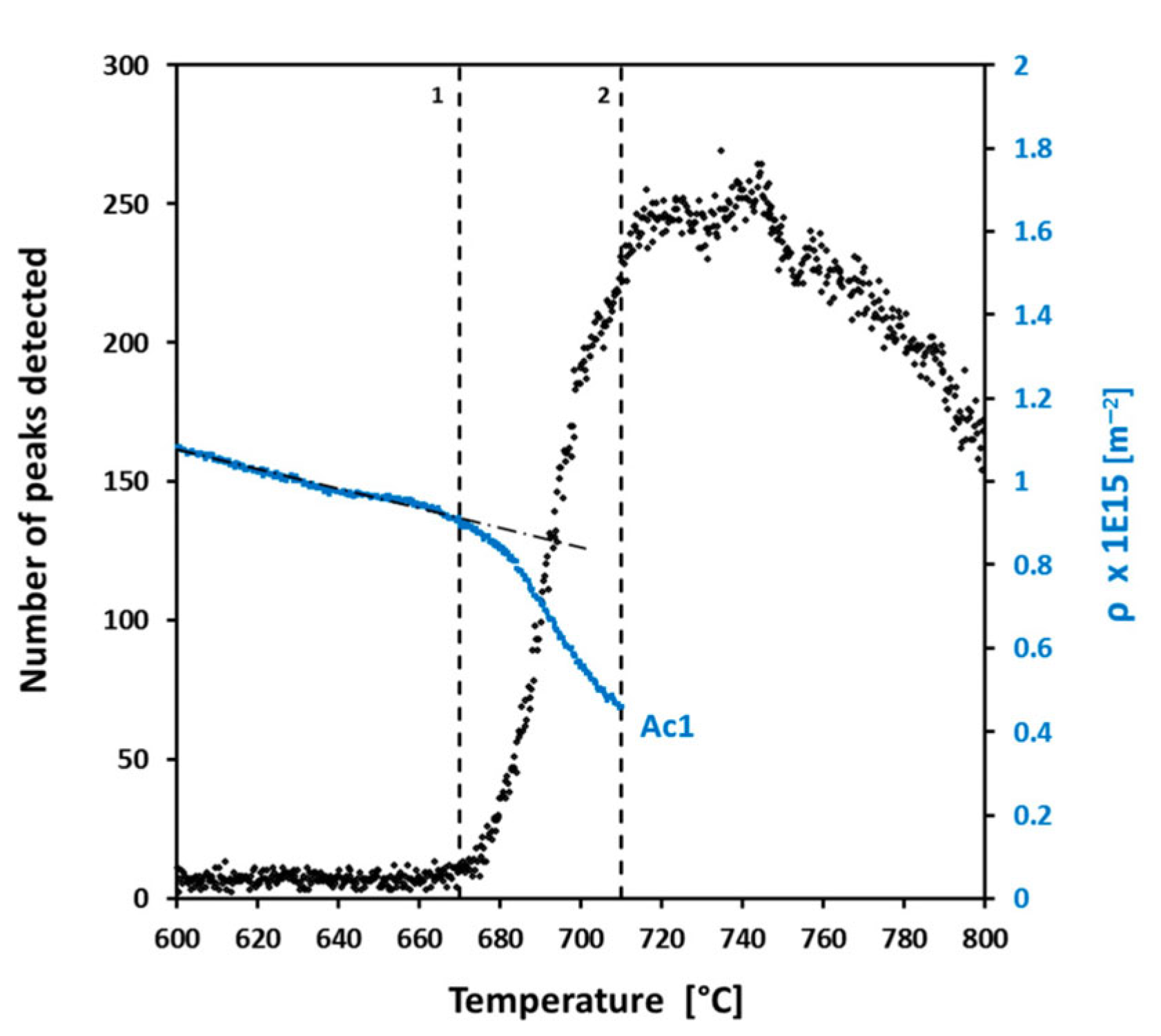

4.2. Steel

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The application of an in situ neutron technique to HPT-processed CoCrFeNi alloy and 316L stainless steel probes sequential thermal microstructural evolution, as revealed through the evolution of diffraction peak profiles during heat treatment. This innovative methodology opens new pathways for effectively reducing residual strain/stress in as-printed metals through plastic deformation and subsequent thermal treatments. Furthermore, mechanical examinations revealed that short-term annealing of nanograins can induce unexpected hardening, providing ways to tailor the mechanical properties of nanostructured materials.

- (2)

- Ti-45Al-7.5Nb alloys under different conditions were investigated by in situ neutron diffraction during heating–cooling cycles. For the powder-metallurgical alloy, lattice thermal anisotropy was observed: (1) the ordering of Ti and Al layers on the γ-021 planes remained constant, while ordering on other planes was enhanced; (2) the activation of energetically favorable Burgers vectors in the γ-phase was detected. Whereas, HPT induced isotropic atomic disorder, resulting in an earlier disorder recovery temperature in the HPT-processed TiAl alloys during heating.

- (3)

- A high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction approach was employed to investigate plastically deformed magnesium alloys during annealing, with time- and space-resolved measurements to track phases and microstructure in real time. Quantitative evaluations of lattice parameters and thermal expansion coefficients for both matrix and intermetallic were obtained. Upon heating, precipitate dissolution, recovery, recrystallization, and grain rotation phenomena were clearly identified.

- (4)

- Cold-rolled steel was subjected to in situ high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction to monitor recovery, recrystallization, and austenite transformation during annealing. Recovery began at 653 K, recrystallization at 943 K, and austenite transformation at 983 K. A new diffraction-spot counting method quantified recrystallization kinetics, enabling simultaneous, real-time characterization of coupled metallurgical processes in steel.

- (1)

- Multidimensional micro-beam diffraction for heterogenous nanostructures. Applying microbeam-based neutron and synchrotron diffraction techniques to heterogeneous nanostructured materials could enable detailed crystallographic information to be obtained, such as phase determination, residual stress evolution, and grain rotation behavior.

- (2)

- Integration of multiscale characterization techniques. The rapid development of neutron and synchrotron techniques, together with advanced complementary tools including transmission electron microscopy and three-dimensional atom probe tomography, is bridging multiple length scales from the nanometer to the millimeter. These integrated approaches aim to elucidate the spatial distribution and evolution of chemical and crystallographic short- and long-range order, thereby providing critical insights to guide the design and fabrication of advanced structural and functional materials.

- (3)

- Coupling experimental data with deformation modeling. By constructing databases of stress, strain and microstructure derived from neutron and synchrotron measurements, and integrating them with various plastic deformation models, it may become possible to reveal the evolution of microstructural units across multiple length scales under realistic temperature and stress conditions, particularly regarding the redistribution of stress and strain, as well as the behavior of dislocation and twinning.

- (4)

- Incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have demonstrated remarkable success in processing and analyzing electron microscopy data. Their application to the analysis of synchrotron and neutron scattering data, especially for systems with complex lattice dynamics, may offer powerful new solutions to existing challenges in measurement, data interpretation, and characterization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gubicza, J.; El-Tahawy, M.; Huang, Y.; Choi, H.; Choe, H.; Lábár, J.L.; Langdon, T.G. Microstructure, Phase Composition and Hardness Evolution in 316L Stainless Steel Processed by High-Pressure Torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 657, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ding, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties of AlCoCrFeNi2.1 Eutectic High-Entropy Alloys Processed by High-Pressure Torsion. Materials 2024, 17, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzeddine, H.; Bradai, D.; Baudin, T.; Langdon, T.G. Texture Evolution in High-Pressure Torsion Processing. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 125, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Whitfield, R.E.; Xu, W.; Buslaps, T.; Yeoh, L.A.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.; Xia, K. In Situ Synchrotron High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction Analysis on Phase Transformations in Ti–Al Alloys Processed by Equal-Channel Angular Pressing. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2009, 16, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A.; Rackel, M.W.; Pyczak, F. How Rapid Heating and Quenching Cycles Affect Phase Evolution in Advanced γ-TiAl Alloys: An in Situ Synchrotron Radiation Study. MRS Commun. 2025, 15, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Ding, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Almer, J.; Guo, F.; Ren, Y. Temperature-Dependent Micromechanical Behavior of Medium-Mn Transformation-Induced-Plasticity Steel Studied by in Situ Synchrotron X-Ray Diffraction. Acta Mater. 2017, 141, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Takata, N.; Wang, W.; Kawasaki, M. Recrystallization-Accelerated Precipitation, Structural Evolution, and Residual Stress Relaxation in Nanostructured Al–Cu–Li Alloy: An in Situ Microbeam Synchrotron High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction Study. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 18307–18331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Xu, P.; Shiro, A.; Zhang, S.; Yukutake, E.; Shobu, T.; Akita, K. Abnormal Grain Growth: A Spontaneous Activation of Competing Grain Rotation. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2300470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Han, J.-K.; Blankenburg, M.; Lienert, U.; Harjo, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Xu, P.; Yukutake, E.; Kawasaki, M. Recrystallization of Bulk Nanostructured Magnesium Alloy AZ31 after Severe Plastic Deformation: An in Situ Diffraction Study. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 5831–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces, G.; Medina, J.; Chávez, B.; Perez, P.; Barea, R.; Stark, A.; Schell, N.; Adeva, P. Load Partitioning Between Mg17Al12 Precipitates and Mg Phase in the AZ91 Alloy Using In-Situ Synchrotron Radiation Diffraction Experiments. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2021, 52, 2732–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkusare, R. A Critical Evaluation of Microstructure-Texture-Mechanical Behavior Heterogeneity in High Pressure Torsion Processed CoCuFeMnNi High Entropy Alloy. Mater. Sci. 2020, 782, 139187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanisenko, Y.; Skrotzki, W.; Chulist, R.; Lippmann, T.; Kurmanaeva, L. Texture Development in a Nanocrystalline Pd–Au Alloy Studied by Synchrotron Radiation. Scr. Mater. 2012, 66, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, P.; Shiro, A.; Zhang, S.; Shobu, T.; Yukutake, E.; Akita, K.; Zolotoyabko, E.; Liss, K.-D. Heat-Induced Structural Changes in Magnesium Alloys AZ91 and AZ31 Investigated by in Situ Synchrotron High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 21446–21459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselova, T.; Malinov, S.; Sha, W.; Zhecheva, A. High-Temperature Synchrotron X-Ray Diffraction Study of Phases in a Gamma TiAl Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 371, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoelzer, T.; Liss, K.-D.; Kirchlechner, C.; Mayer, S.; Stark, A.; Peel, M.; Clemens, H. An In-Situ High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction Study on the Hot-Deformation Behavior of a β-Phase Containing TiAl Alloy. Intermetallics 2013, 39, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Stark, A.; Bartels, A.; Clemens, H.; Buslaps, T.; Phelan, D.; Yeoh, L.A. Directional Atomic Rearrangements During Transformations Between the A- and γ-Phases in Titanium Aluminides. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, W.; Broda, M.; Brusch, G.; Dantz, D.; Liss, K.-D.; Pyzalla, A.; Schmackers, T.; Tschentscher, T. Evaluation of Residual Stresses in the Bulk of Materials by High Energy Synchrotron Diffraction. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 1998, 17, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, H.J.; Wcislak, L.; Klein, H.; Garbe, U.; Schneider, J.R. Texture and Microstructure Analysis with High-Energy Synchrotron Radiation. Mater. Sci. Forum 2002, 408–412, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Callaghan, M.D.; Liss, K.-D. Deformation Mechanisms of Twinning-Induced Plasticity Steel under Shock-Load: Investigated by Synchrotron X-Ray Diffraction. Quantum Beam Sci. 2019, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Carr, D.G.; Callaghan, M.D.; Liss, K.-D.; Li, H. Deformation Mechanisms of Twinning-Induced Plasticity Steels: In Situ Synchrotron Characterization and Modeling. Scr. Mater. 2010, 62, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Bartels, A.; Schreyer, A.; Clemens, H. High-Energy X-Rays: A Tool for Advanced Bulk Investigations in Materials Science and Physics. Texture Stress Microstruct. 2003, 35, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Liss, K.; Garbe, U.; Daniels, J.; Kirstein, O.; Li, H.; Dippenaar, R. From Single Grains to Texture. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2009, 11, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Yan, K. Thermo-Mechanical Processing in a Synchrotron Beam. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 528, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Gan, W.; Esling, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Maawad, E.; Stark, A.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Elastic Strain Induced Abnormal Grain Growth in Graphene Nanosheets (GNSs) Reinforced Copper (Cu) Matrix Composites. Acta Mater. 2020, 200, 338350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Naeem, M.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Harjo, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Wang, B.; Wu, X.; Lan, S.; Wu, Z.; et al. Stacking Fault Driven Phase Transformation in CrCoNi Medium Entropy Alloy. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, W.H.; Wang, X.L.; Ma, D.; Stoica, A.D.; Nieh, T.G.; He, Z.B.; Lu, Z.P. In-Situ Neutron Diffraction Study of Deformation Behavior of a Multi-Component High-Entropy Alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 051910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Krishnan, V.B.; Padula, S.A.; Noebe, R.D.; Brown, D.W.; Clausen, B.; Vaidyanathan, R. Measurement of the Lattice Plane Strain and Phase Fraction Evolution during Heating and Cooling in Shape Memory NiTi. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 141906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, S.; Yan, K.; Mayer, S.; Schmoelzer, T.; Reid, M.; Dippenaar, R.; Clemens, H.; Liss, K.-D. Phase Transition and Ordering Behavior of Ternary Ti–Al–Mo Alloys Using in-Situ Neutron Diffraction. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 102, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyzalla, A.; Reimers, W.; Liss, K.D. A Comparison of Neutron and High Energy Synchrotron Radiation as Tools for Texture and Stress Analysis. Mater. Sci. Forum 2000, 347–349, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daymond, M.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Sivia, D.S. Analysis of Neutron Diffraction Strain Measurement Data from a Round Robin Sample. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 2002, 37, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Harjo, S.; Abe, J.; Xu, P.; Aizawa, K.; Akita, K. Effects of Gauge Volume on Pseudo-Strain Induced in Strain Measurement Using Time-of-Flight Neutron Diffraction. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2013, 715, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Han, J.-K.; Dippenaar, R.J.; Kawasaki, M. On the Thermal Evolution of High-Pressure Torsion Processed Titanium Aluminide. Mater. Lett. 2021, 304, 130650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, K.; Neikter, M.; Ekh, M.; Harjo, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Woracek, R.; Hansson, T.; Pederson, R. In Situ Neutron Diffraction Study of Strain Evolution and Load Partitioning During Elevated Temperature Tensile Test in HIP-Treated Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion Manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. JOM 2025, 77, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarre, C.; Sumarli, S.; Malamud, F.; Polatidis, E.; Strobl, M.; Logé, R.E. In-Situ Neutron Diffraction Revealing Microstructure Changes during Laser Powder Bed Fusion and in-Situ Laser Heat Treatments of 316L and 316L-Al1. Mater. Des. 2025, 251, 113727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, W.; Huang, E.-W.; Yeh, J.-W.; Choo, H.; Lee, C.; Tu, S.-Y. In-Situ Neutron Diffraction Studies on High-Temperature Deformation Behavior in a CoCrFeMnNi High Entropy Alloy. Intermetallics 2015, 62, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.S.; Wilks, G.B.; Mauger, L.; Muñoz, J.A.; Senkov, O.N.; Michel, E.; Horwath, J.; Semiatin, S.L.; Stone, M.B.; Abernathy, D.L.; et al. Absence of Long-Range Chemical Ordering in Equimolar FeCoCrNi. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 251907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Han, J.-K.; Liu, X.; Onuki, Y.; Kuzminova, Y.O.; Evlashin, S.A.; Pesin, A.M.; Zhilyaev, A.P.; Liss, K.-D. In Situ Heating Neutron and X-Ray Diffraction Analyses for Revealing Structural Evolution during Postprinting Treatments of Additive-Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, J.-K.; Onuki, Y.; Kuzminova, Y.O.; Evlashin, S.A.; Kawasaki, M.; Liss, K.-D. In Situ Neutron Diffraction Investigating Microstructure and Texture Evolution upon Heating of Nanostructured CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, S.; Yan, K.; Carr, D.G.; Harrison, R.P.; Dippenaar, R.J.; Reid, M.; Liss, K.-D. Defect Dynamics in Polycrystalline Zirconium Alloy Probed in Situ by Primary Extinction of Neutron Diffraction. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 063513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; He, H.; Harjo, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Zhang, F.; Wang, B.; Lan, S.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Lu, Z.; et al. Extremely High Dislocation Density and Deformation Pathway of CrMnFeCoNi High Entropy Alloy at Ultralow Temperature. Scr. Mater. 2020, 188, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dippenaar, R.J.; Han, J.-K.; Kawasaki, M.; Liss, K.-D. Phase Transformation and Structure Evolution of a Ti-45Al-7.5Nb Alloy Processed by High-Pressure Torsion. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 787, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotoyabko, E. Basic Concepts of X-Ray Diffraction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, W.; Pyzalla, A.; Schreyer, A.; Clemens, H. Diffraction Methods in Engineering Materials Science; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schmoelzer, T.; Liss, K.-D.; Staron, P.; Mayer, S.; Clemens, H. The Contribution of High-Energy X-Rays and Neutrons to Characterization and Development of Intermetallic Titanium Aluminides. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2011, 13, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, H.; Haga, K.; Teshigawara, M.; Aso, T.; Meigo, S.-I.; Kogawa, H.; Naoe, T.; Wakui, T.; Ooi, M.; Harada, M.; et al. Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex I: Pulsed Spallation Neutron Source. Quantum Beam Sci. 2017, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Kawakita, Y.; Itoh, S.; Abe, J.; Aizawa, K.; Aoki, H.; Endo, H.; Fujita, M.; Funakoshi, K.; Gong, W.; et al. Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility (MLF) at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex II: Neutron Scattering Instruments. Quantum Beam Sci. 2017, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovid’ko, I.A.; Valiev, R.Z.; Zhu, Y.T. Review on Superior Strength and Enhanced Ductility of Metallic Nanomaterials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 94, 462–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Langdon, T.G. Principles of Equal-Channel Angular Pressing as a Processing Tool for Grain Refinement. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2006, 51, 881–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R. Nanostructuring of Metals by Severe Plastic Deformation for Advanced Properties. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Estrin, Y.; Horita, Z.; Langdon, T.G.; Zehetbauer, M.J.; Zhu, Y.T. Fundamentals of Superior Properties in Bulk NanoSPD Materials. Mater. Res. Lett. 2016, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Islamgaliev, R.K.; Alexandrov, I.V. Bulk Nanostructured Materials from Severe Plastic Deformation. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2000, 45, 103–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilyaev, A.P.; Langdon, T.G. Using High-Pressure Torsion for Metal Processing: Fundamentals and Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 893–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.J.; Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Residual Stress Part 1—Measurement Techniques. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2001, 17, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, R.D.; Hughes, D.A.; Humphreys, F.J.; Jonas, J.J.; Jensen, D.J.; Kassner, M.E.; King, W.E.; McNelley, T.R.; McQueen, H.J.; Rollett, A.D. Current Issues in Recrystallization: A Review. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1997, 238, 219–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bei, H.; Otto, F.; Pharr, G.M.; George, E.P. Recovery, Recrystallization, Grain Growth and Phase Stability of a Family of FCC-Structured Multi-Component Equiatomic Solid Solution Alloys. Intermetallics 2013, 46, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, S.; Bae, J.W.; Asghari-Rad, P.; Park, J.M.; Kim, H.S. Annealing-Induced Hardening in High-Pressure Torsion Processed CoCrNi Medium Entropy Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 734, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubicza, J. Annealing-Induced Hardening in Ultrafine-Grained and Nanocrystalline Materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1900507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hansen, N.; Tsuji, N. Hardening by Annealing and Softening by Deformation in Nanostructured Metals. Science 2006, 312, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaoui, A.; Van Swygenhoven, H.; Derlet, P.M. On Non-Equilibrium Grain Boundaries and Their Effect on Thermal and Mechanical Behaviour: A Molecular Dynamics Computer Simulation. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 3927–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, T.S.; Skiba, N.V.; Mavlyutov, A.M.; Murashkin, M.Y.; Valiev, R.Z.; Gutkin, M.Y. Hardening by Annealing and Implementation of High Ductility of Ultra-Fine Grained Aluminum: Experiment and Theory. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2018, 57, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, P.; Weertman, J.; Barker, J.; Siegel, R. Small Angle Neutron Scattering from Nanocrystalline Pd and Cu Compacted at Elevated Temperatures. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 2011, 351, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheriau, S.; Zhang, Z.; Kleber, S.; Pippan, R. Deformation Mechanisms of a Modified 316L Austenitic Steel Subjected to High Pressure Torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 2776–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahawy, M.; Huang, Y.; Choi, H.; Choe, H.; Lábár, J.L.; Langdon, T.G.; Gubicza, J. High Temperature Thermal Stability of Nanocrystalline 316L Stainless Steel Processed by High-Pressure Torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shuro, I.; Umemoto, M.; Ho-Hung, K.; Todaka, Y. Annealing Behavior of Nano-Crystalline Austenitic SUS316L Produced by HPT. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 556, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Han, J.-K.; Liu, X.; Moon, S.-C.; Liss, K.-D. Synchrotron High-Energy X-Ray & Neutron Diffraction, and Laser-Scanning Confocal Microscopy: In-Situ Characterization Techniques for Bulk Nanocrystalline Metals. Mater. Trans. 2023, 64, 1683–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahawy, M.; Huang, Y.; Um, T.; Choe, H.; Lábár, J.L.; Langdon, T.G.; Gubicza, J. Stored Energy in Ultrafine-Grained 316L Stainless Steel Processed by High-Pressure Torsion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2017, 6, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chladil, H.F.; Clemens, H.; Leitner, H.; Bartels, A.; Gerling, R.; Schimansky, F.-P.; Kremmer, S. Phase Transformations in High Niobium and Carbon Containing γ-TiAl Based Alloys. Intermetallics 2006, 14, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.J.; Hagen, M.E.; Noakes, T.J. Wombat: The High-Intensity Powder Diffractometer at the OPAL Reactor. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2006, 385–386, 1013–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, L.A.; Liss, K.-D.; Bartels, A.; Chladil, H.; Avdeev, M.; Clemens, H.; Gerling, R.; Buslaps, T. In Situ High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction Study and Quantitative Phase Analysis in the A+γ Phase Field of Titanium Aluminides. Scr. Mater. 2007, 57, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechtman, D.; Blackburn, M.J.; Lipsitt, H.A. The Plastic Deformation of TiAl. Metall. Trans. 1974, 5, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobu, T.; Tozawa, K.; Shiwaku, H.; Konishi, H.; Inami, T.; Harami, T.; Mizuki, J. Wide Band Energy Beamline Using Si (111) Crystal Monochromators at BL22XU in SPring-8. AIP Conf. Proc. 2007, 879, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Yan, K.; Reid, M. Physical Thermo-Mechanical Simulation of Magnesium: An in-Situ Diffraction Study. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 601, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Prado, M.T.; Del Valle, J.A.; Contreras, J.M.; Ruano, O.A. Microstructural Evolution during Large Strain Hot Rolling of an AM60 Mg Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2004, 50, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K.-D.; Schmoelzer, T.; Yan, K.; Reid, M.; Peel, M.; Dippenaar, R.; Clemens, H. In Situ Study of Dynamic Recrystallization and Hot Deformation Behavior of a Multiphase Titanium Aluminide Alloy. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 113526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.L. The AI-Mg(Aluminum-Magnesium)System. J. Phase Equilibria 1982, 3, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynor, G.; Hume-Rothery, W. A Technique for the X-Ray Powder Photography of Reactive Metals and Alloys with Special Reference to the Lattice Spacing of Magnesium at High Temperatures Locality. J. Inst. Met. 1939, 65, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, B.G. The Thermal Expansion of Anisotropic Metals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1953, 25, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; Wang, H.-Y.; Wang, T.; Zha, M.; Hua, Z.-M.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Q.-C. Influences of Pre-Existing Mg17Al12 Particles on Static Recrystallization Behavior of Mg-Al-Zn Alloys at Different Annealing Temperatures. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 787, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busk, R.S. Lattice Parameters of Magnesium Alloys. JOM 1950, 2, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Teixeira, J.; Geandier, G.; Hell, J.-C.; Bonnet, F.; Salib, M.; Allain, S.Y.P. Real-Time Investigation of Recovery, Recrystallization and Austenite Transformation during Annealing of a Cold-Rolled Steel Using High Energy X-Ray Diffraction (HEXRD). Metals 2018, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Techniques | Energy (keV) | Wavenumber (Å−1) | Attenuation Length (Iμ) (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | Al | Fe | Cu | Au | |||

| Neutrons | 33000 | 4.05 | 1700 | 800 | 45 | 37.2 | 2 |

| Synchrotron | 100 | 50.7 | 37 | 22 | 3.8 | 0.037 | 0.249 |

| Laboratory (Cu Kα) | 8 | 4.05 | 0.144 | 0.074 | 0.0042 | 0.021 | 0.00259 |

| Aspect | Neutrons | Synchrotron (High-Energy X-Rays) |

|---|---|---|

| Source intensity/flux | low | high |

| Beam size | cm | nm–mm |

| Sample size | large volumes (cm3) | very small (mm3) |

| Penetration depth in metals | cm–m | mm–cm |

| Sensitivity to light/heavy elements | excellent | poor |

| Magnetism sensitivity | strong | weak |

| Detector technology | slow and less efficient | advanced, fast |

| Experiment speed | minutes to hours | seconds to minutes |

| Temperature | Dislocation Density, ρ [1015 m−2] | Grain Size, D [nm] |

|---|---|---|

| 303 K | 6.1 | 29 |

| 643 K | 5 | 30.2 |

| 800 K | 4 | 30.5 |

| 905 K | 0.3 | 120 |

| 1000 K | 0.033 | 153 |

| 1273 K | 0.030 | 479.5 |

| Technique | Materials | Processing Methods | In Situ Temperature Conditions | Main Diffraction Features | Mechanical Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutron | CoCrFeNi | 3D printing and HPT (15 turns, 6 GPa, RT, 1 rpm) | 300–1000 K at 4 K·min−1, furnace cooling, 1000–1273 K at 9 K·min−1 | Dislocation density, grain size, lattice expansion | Hardness increases during short-term annealing |

| Neutron | 316L stainless steel | 3D printing and HPT (15 turns, 6 GPa, RT, 1 rpm) | 300–1240 K at 4 K·min−1, furnace cooling, | Dislocation density, grain size, lattice expansion | Hardness increases during short-term annealing |

| Neutron | Ti-Al | HPT (5 turns, 6 GPa, RT, 1 rpm) | 300–1440 K at 4.2 K·min−1, furnace cooling, | Order/disorder transition, thermal anisotropy | - |

| Synchrotron | AZ91/AZ31 | Rolling | 300–773 K at 7.5 K·min−1, furnace cooling, | Phase transformation, Lattice strain, grain rotation | - |

| Synchrotron | Steel | Cold rolling | 300–1073 K at 180 K·min−1 | Phase transformation, recovery, recrystallization | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Lei, Z.; Men, Z. In Situ Neutron and Synchrotron X-Ray Analysis of Structural Evolution on Plastically Deformed Metals During Annealing. Coatings 2025, 15, 1438. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121438

Liu X, Lei Z, Men Z. In Situ Neutron and Synchrotron X-Ray Analysis of Structural Evolution on Plastically Deformed Metals During Annealing. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1438. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121438

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaojing, Zheng Lei, and Zhengxing Men. 2025. "In Situ Neutron and Synchrotron X-Ray Analysis of Structural Evolution on Plastically Deformed Metals During Annealing" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1438. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121438

APA StyleLiu, X., Lei, Z., & Men, Z. (2025). In Situ Neutron and Synchrotron X-Ray Analysis of Structural Evolution on Plastically Deformed Metals During Annealing. Coatings, 15(12), 1438. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121438