Study on the Room-Temperature Rapid Curing Behavior and Mechanism of HDI Trimer-Modified Epoxy Resin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Primary Materials

2.2. Primary Instruments and Equipment

2.3. Characterization and Analysis

- (1)

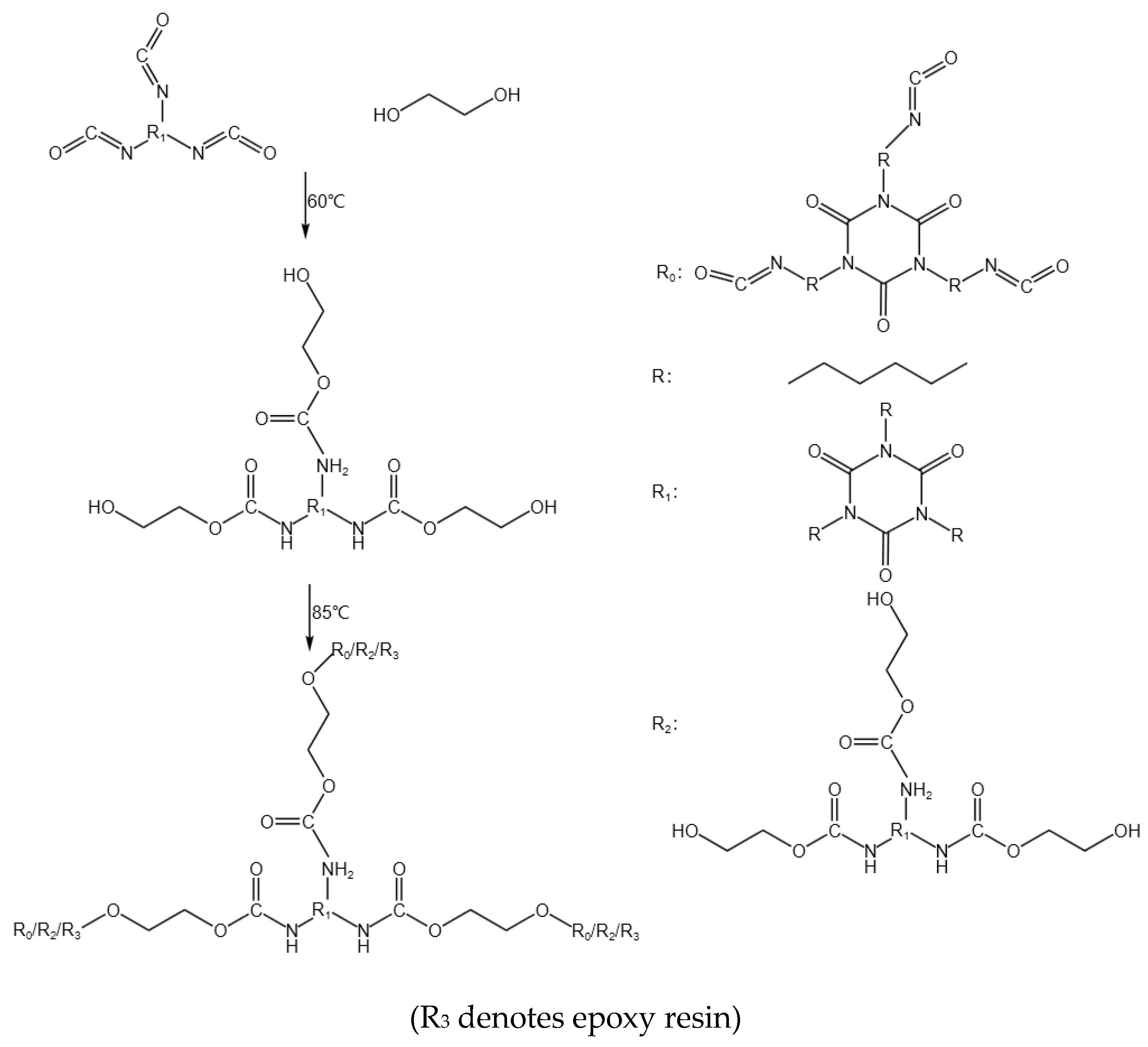

- Preparation Process

- (2)

- Synthesis Pathway

3. Analysis of Results

3.1. Analysis of Curing Behavior and Crosslink Density

3.2. Molecular Structure Analysis

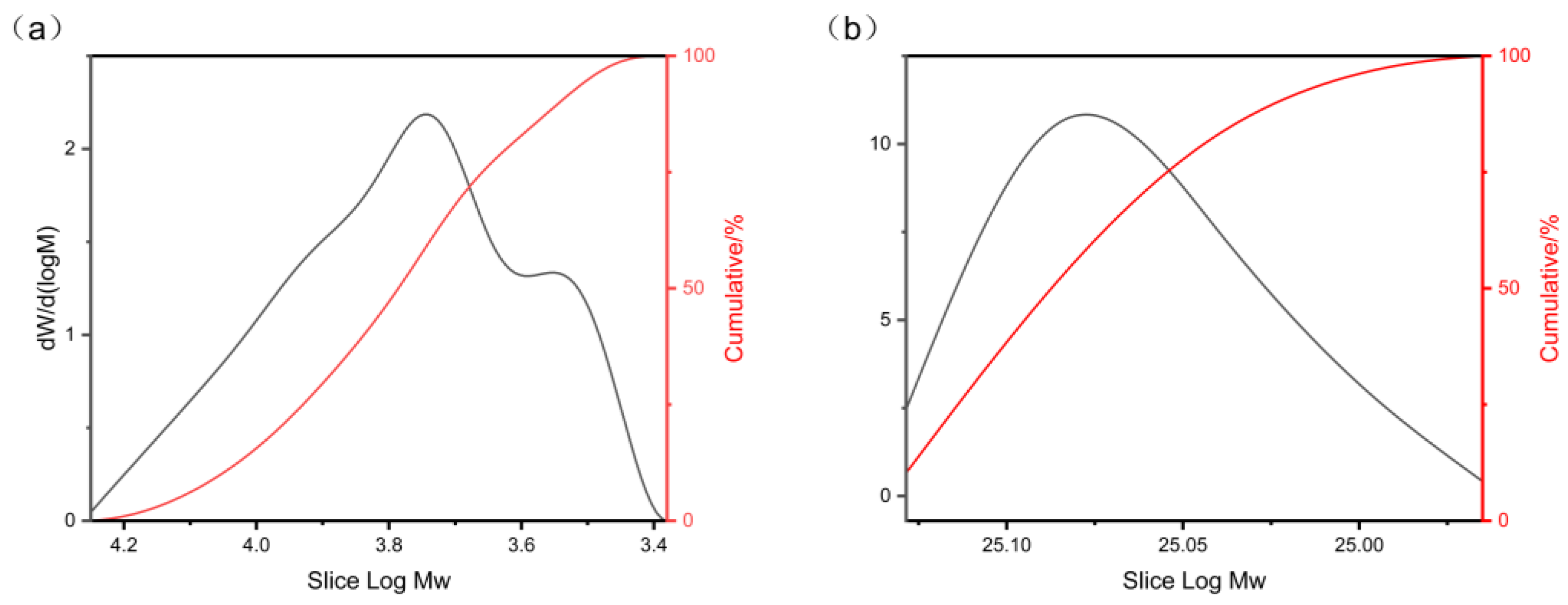

3.3. Molecular Weight Analysis

3.4. Study on Mechanical Properties

3.5. Microstructural Analysis

3.6. Study on Heat Resistance Properties

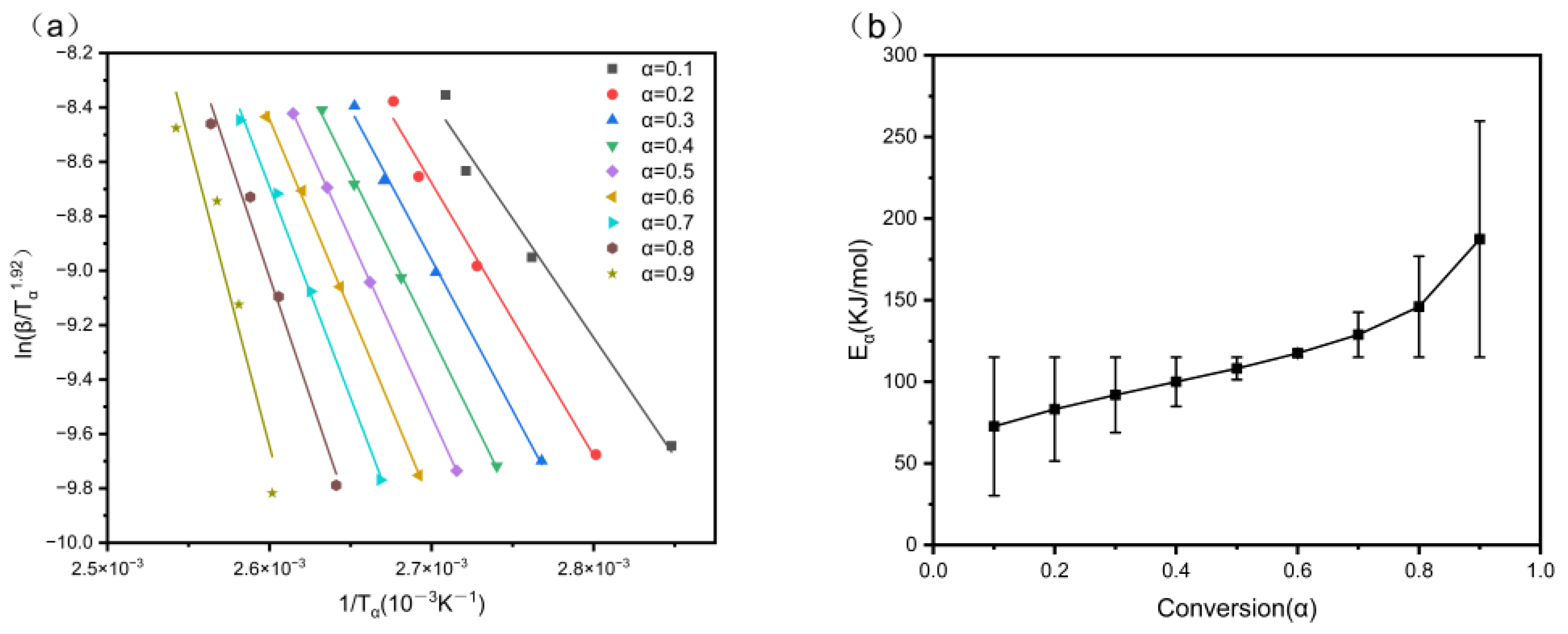

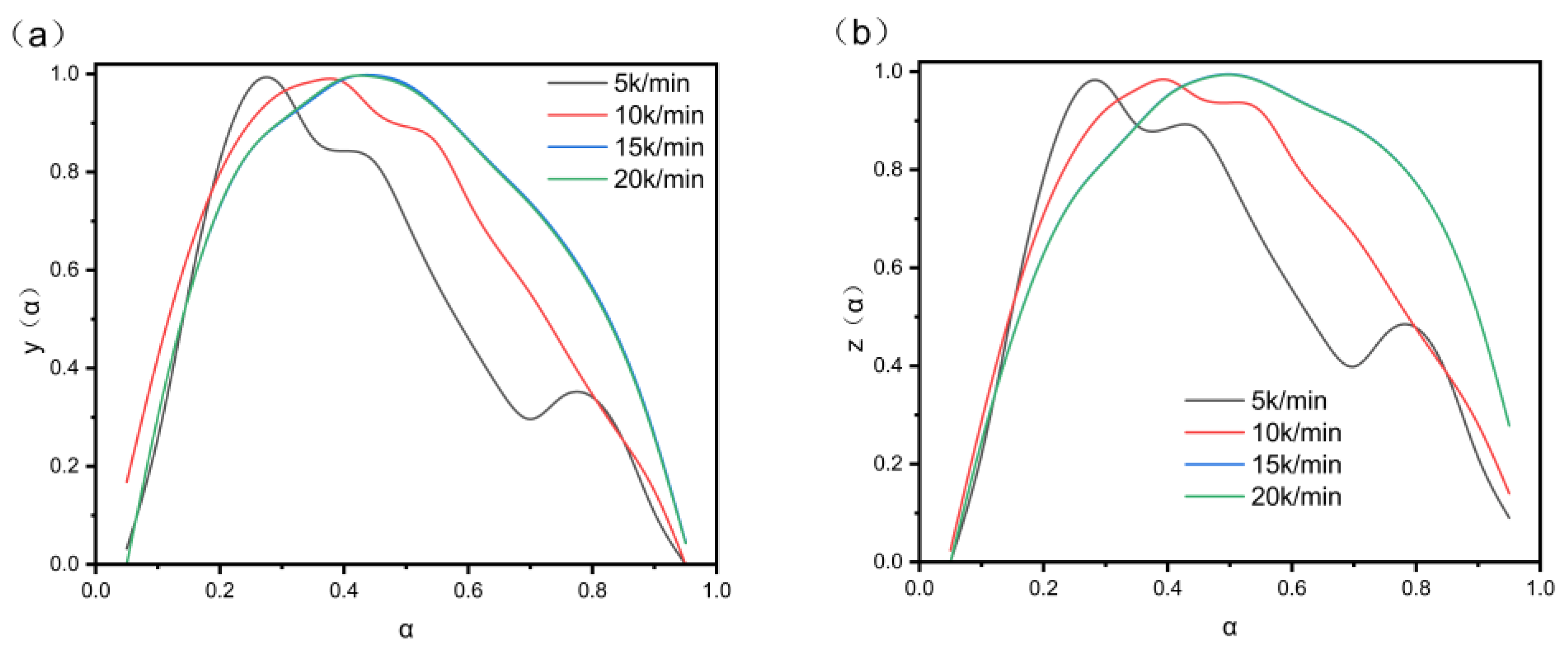

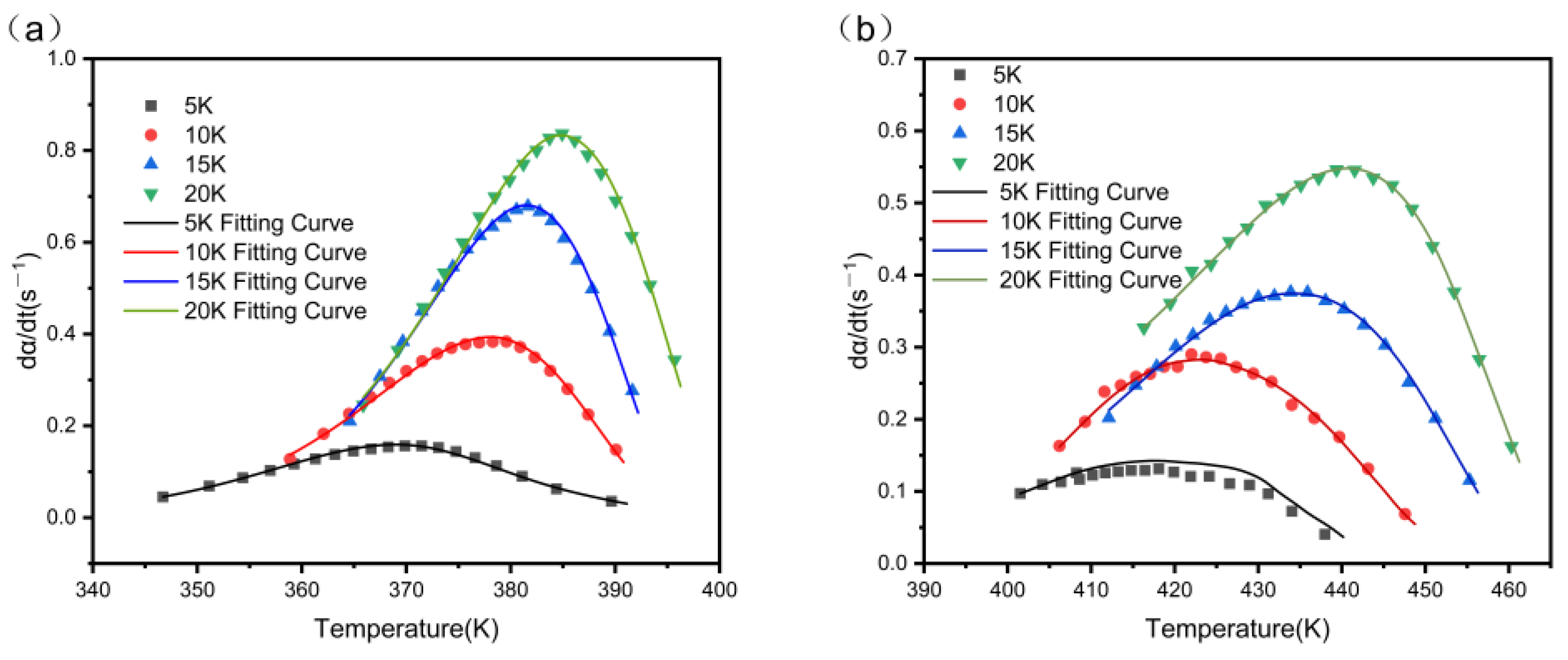

3.7. Non-Isothermal Curing Kinetic Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreira, V.B.; Alemán, C.; Rintjema, J.; Bravo, F.; Kleij, A.W.; Armelin, E. A biosourced epoxy resin for adhesive thermoset applications. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouser, T.; Nur, F.; Aliyu, A.; Altaf, F.; Zulfiqar, H.; Alhems, L.M. Applications of epoxy resins as a coating technology in fluid systems. ChemBioEng Rev. 2025, 12, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.; Peng, C.; Wu, Z. Epoxy-functionalized polysiloxane reinforced epoxy resin for cryogenic application. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 46930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, Y. Preparation of epoxy resin elastic particles and their application in oil well cement. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 141, e55053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, R.; Liu, C.; Mo, J. Application of zno/epoxy resin superhydrophobic coating for buoyancy enhancement and drag reduction. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2022, 651, 129714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, T.; Cai, W.; Pan, Z.; Wang, J.; Derradji, M.; Liu, W.B. Preparation, dielectric and thermomechanical properties of a novel epoxy resin system cured at room temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 24902–24909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jin, C.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Qi, H. Mechanism and properties of aromatic amines room temperature catalyzed curing of cyanate ester and epoxy resin system. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e00501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zou, F.; Guo, W.; Zhang, G. Effect of accelerator on properties of epoxy resin re-prepared from alcoholysis recycling. High Volt. 2024, 10, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Huang, A.; Jiang, Q. Preparation of terminal isocyanate-based polyurethane prepolymer and its toughening and modification of epoxy resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liao, B.; Wang, K.; Dai, Y.; Huang, J.; Pang, H. Synthesis, curing kinetics, mechanical and thermal properties of novel cardanol-based curing agents with thiourea. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 105744–105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, H.; Qu, Z. Numerical simulation and comparison of the mechanical behavior of toughened epoxy resin by different nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31123–31134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, F.; Du, X. Molecular dynamics simulation of crosslinking process and mechanical properties of epoxy under the accelerator. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 140, e53302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pan, Z.; Han, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, F. Preparation of low-temperature curing single-component epoxy adhesives with sedimentation coated accelerators. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e56165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, B.; Wu, G.P. Dual sacrificial strategy toward tough and recyclable CO2-sourced epoxy thermosets. Angew. Chem. 2025, e19660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chu, D.; Dai, S.; Wang, X.; Du, S.; Zhang, F.; Ma, S. Dynamic ester-enabled recyclable epoxy adhesives from glucose and soybean oil: Storage-stable, high-adhesion, and on-demand degradable. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 17, 9226–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, J. The influence of tertiary amine accelerators on the curing behaviors of epoxy/anhydride systems. Thermochim. Acta. 2014, 577, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, A.; Aversano, R.; D'Ilario, L.; Di Lisio, V.; Francolini, I.; Piozzi, A.; Martinelli, A. Flexible aliphatic poly(isocyanurate–oxazolidone) resins based on poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether and 4,4′-methylene dicyclohexyl diisocyanate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ni, Y.; Li, Z.; He, J.; Zou, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Z.; Cao, S.; Ma, C.; Guo, K. Amino-cyclopropenium h-bonding organocatalysis in cycloaddition of glycidol and isocyanate to oxazolidinone. Mol. Catal. 2023, 548, 113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Wei, W.; Li, X. Facile synthesis of hyperbranched epoxy resin for combined flame retarding and toughening modification of epoxy thermosets. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, H.R.; Ehsani, M.; Khonakdar, H.A. Investigation of the cure kinetics and thermal stability of an epoxy system containing cystamine as curing agent. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2020, 32, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, S.; Guo, A.; Li, J.; Liu, D. The curing kinetics analysis of four epoxy resins using a diamine terminated polyether as curing agent. Thermochim. Acta 2021, 702, 178987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senum, G.I.; Yang, R.T. Rational approximations of the integral of the Arrhenius function. J. Therm. Anal. 1977, 11, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serial Number | E-44 (wt%) | DETA (wt%) | HDI Trimer (wt%) | PEG200 (wt%) | DMP-30 (wt%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | Pure epoxy without accelerators | 10 | 3 | |||

| 2# | Modified epoxy without accelerator | 10 | 3 | 0.049 | 0.025 | |

| 3# | Modified epoxy with accelerator | 10 | 3 | 0.049 | 0.025 | 0.039 |

| Surface Cure Time | Crosslinking Degree | |

|---|---|---|

| 1# | Over 14 h | 87.00% |

| 2# | Over 14 h | 98.13% |

| 3# | 7 h and 30 min | 97.86% |

| Mn | Mw | Mp | PDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure epoxy | 2602 | 3089 | 1389 | 1.18 |

| HDI trimer–PEG-modified Epoxy | 8690 | 13842 | 7944 | 1.59 |

| Elongation at Break (%) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1# | 8.08 | 1.52 |

| 2# | 4.00 | 1.65 |

| 3# | 3.50 | 1.84 |

| Deflection at a Strain of 0.0005 (mm) | Deflection at a Strain of 0.0025 (mm) | Elasticity Flexural Modulus (GPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 0.08 | 0.42 | 2.06 |

| 2# | 0.09 | 0.43 | 3.11 |

| 3# | 0.09 | 0.43 | 3.56 |

| T5% (°C) | T50% (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Residual Sample Mass at 500 °C (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 337.75 | 379.00 | 375.11 | 13.95 |

| 2# | 325.01 | 374.07 | 376.50 | 9.74 |

| 3# | 315.81 | 380.83 | 381.44 | 10.49 |

| β (K/min) | αM (y(α) Peak Value) | αp (DSC Peak Value) | αp∞ (z(α) Peak Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| 10 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| 15 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| 20 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| β (K/min) | αM (y(α) Peak Value) | αp (DSC Peak Value) | αp∞ (z(α) Peak Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| 10 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| 15 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| 20 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| β (K/min) | lnA (s−1) | Average | n | Average | m | Average | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 36.76 | 36.69 | 1.51 | 1.09 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| 10 | 36.58 | 1.02 | −0.02 | 0.96 | |||

| 15 | 36.76 | 0.91 | 0.08 | 0.98 | |||

| 20 | 36.64 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.98 |

| β (K/min) | lnA (s−1) | Average | n | Average | m | Average | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 28.09 | 28.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 28.55 | 1.31 | 0.06 | 0.99 | |||

| 15 | 28.05 | 1.09 | −0.09 | 0.99 | |||

| 20 | 27.78 | 0.97 | −0.06 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Room-Temperature Rapid Curing Behavior and Mechanism of HDI Trimer-Modified Epoxy Resin. Coatings 2025, 15, 1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121427

Wu J, Liu Y, Ma S, Zhang Y. Study on the Room-Temperature Rapid Curing Behavior and Mechanism of HDI Trimer-Modified Epoxy Resin. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121427

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jiali, Yan Liu, Sude Ma, and Yue Zhang. 2025. "Study on the Room-Temperature Rapid Curing Behavior and Mechanism of HDI Trimer-Modified Epoxy Resin" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121427

APA StyleWu, J., Liu, Y., Ma, S., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Study on the Room-Temperature Rapid Curing Behavior and Mechanism of HDI Trimer-Modified Epoxy Resin. Coatings, 15(12), 1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121427