Smartphones as Portable Tools for Reliable Color Determination of Metal Coatings Using a Colorimetric Calibration Card

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

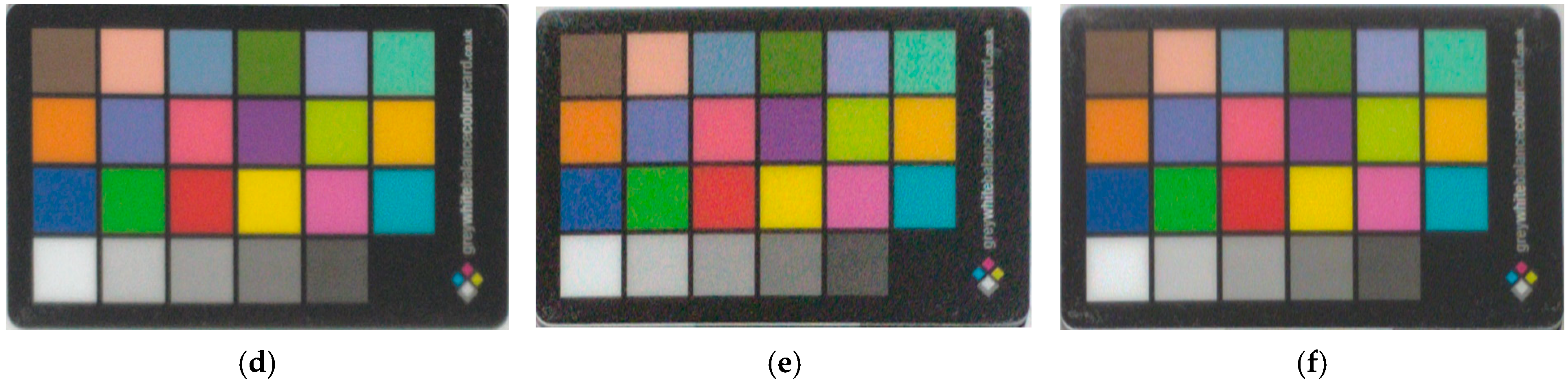

2.1. Color Reference

2.2. Sample Preparation

- Dark black finishes (Auroblack, sample A; Black Gold NR, sample B; Oro Nero 8550, sample C);

- Silvery gray finishes (Rh WO2S, sample D; PdFe 720, sample E);

- Golden yellow finishes (AuFe 8693, sample F; Au 1N 9812, sample G).

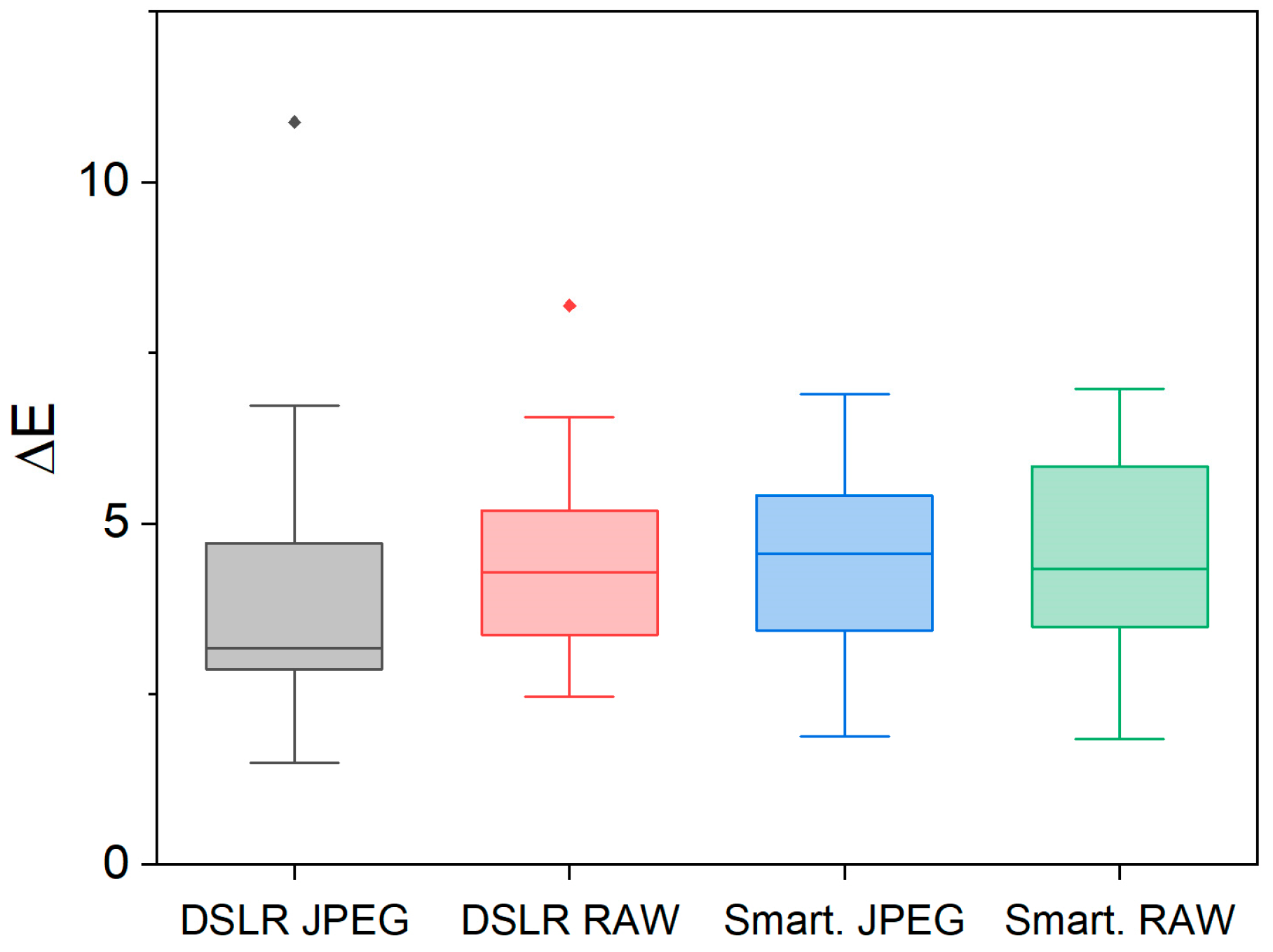

2.3. Color Acquisition

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Eight-Bit RGB Color Space

- True color of the sample: L* = 59.57; a* = 1.67; b* = 4.42.

- Conversion in 8-bit RGB: R = 149.8713; G = 142.1971; B = 135.7984.

- Rounding: R = 150; G = 142; B = 136.

- Back conversion: L* = 59.5329; a* = 1.8655; b* = 4.2529.

- ΔEConv = 0.26.

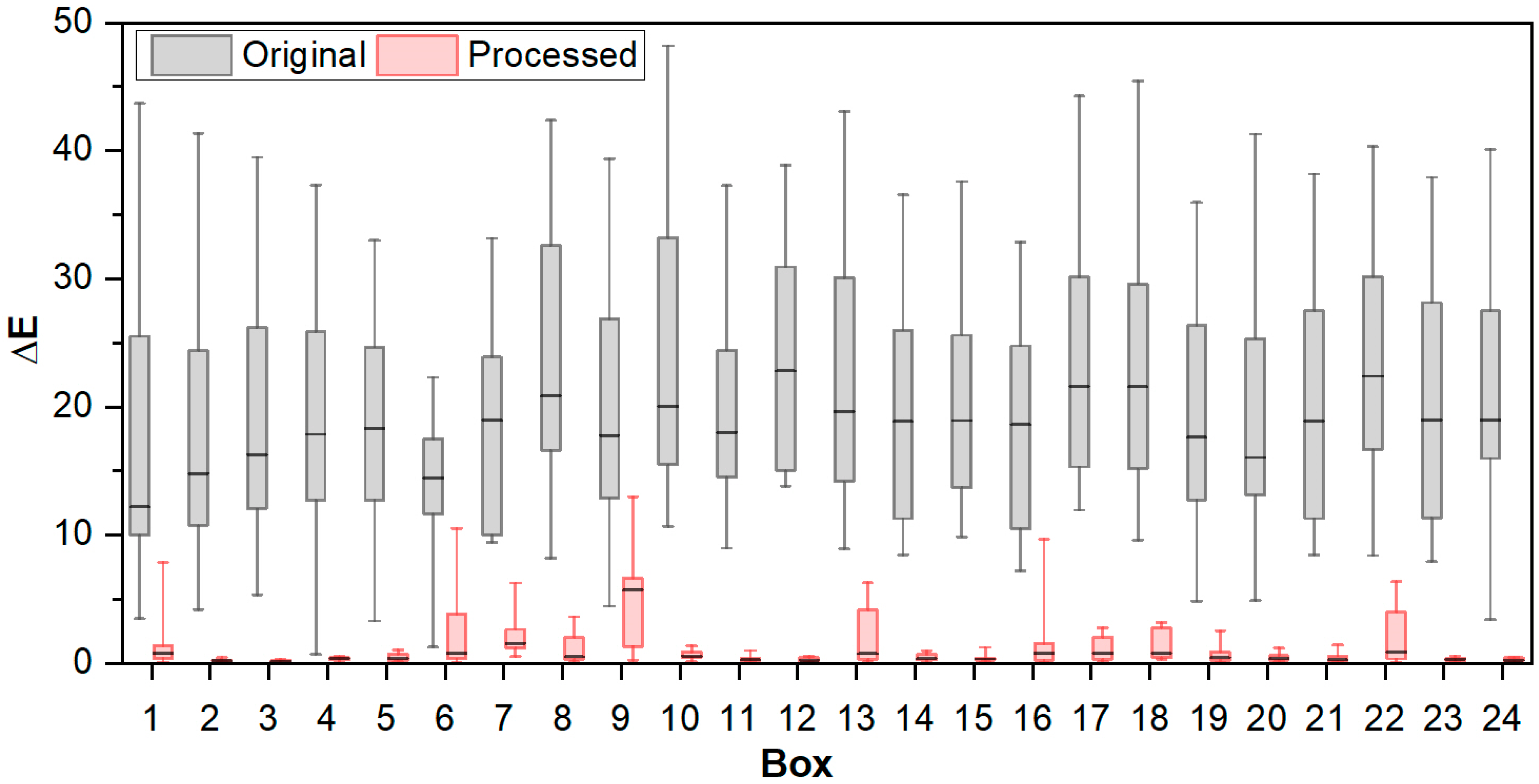

3.2. Colorimetric Reference

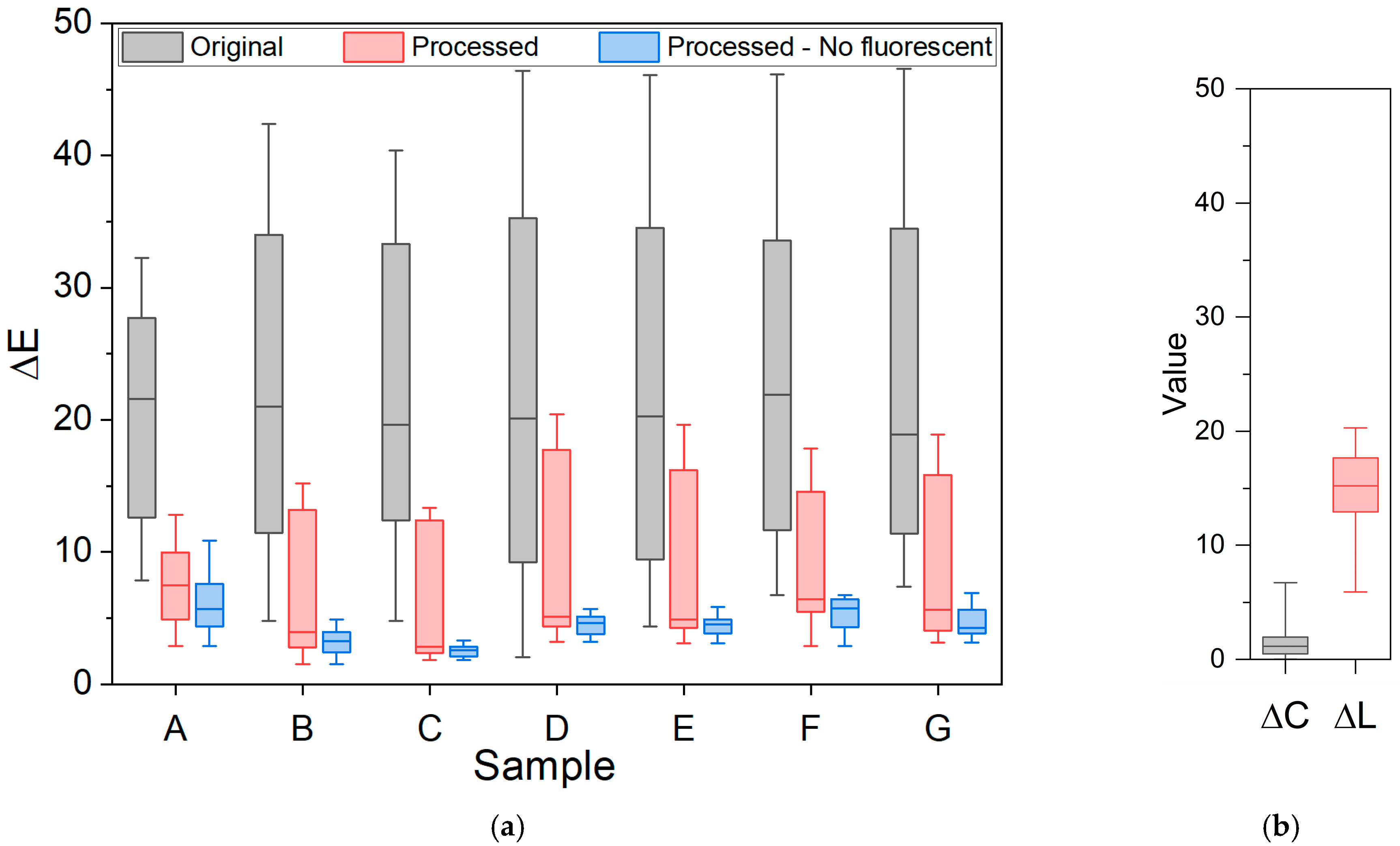

3.3. Color Determination of Metal Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keist, C.N. Quality Control and Quality Assurance in the Apparel Industry; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9781782422327. [Google Scholar]

- Raluca, B. A Review of Color Measurments in the Textile Industry. Ann. Univ. Oradea Fascicle Text. Leatherwork 2016, 17, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Giurlani, W.; Gambinossi, F.; Salvietti, E.; Passaponti, M.; Innocenti, M. Color Measurements in Electroplating Industry: Implications for Product Quality Control. ECS Trans. 2017, 80, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitán-Vallvey, L.F.; López-Ruiz, N.; Martínez-Olmos, A.; Erenas, M.M.; Palma, A.J. Recent developments in computer vision-based analytical chemistry: A tutorial review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 899, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, D.; Caliceti, C.; Zangheri, M.; Mirasoli, M.; Simoni, P.; Roda, A. Smartphone–based enzymatic biosensor for oral fluid L-lactate detection in one minute using confined multilayer paper reflectometry. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goñi, S.M.; Salvadori, V.O. Color measurement: Comparison of colorimeter vs. computer vision system. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubero, S.; Aleixos, N.; Moltó, E.; Gómez-Sanchis, J.; Blasco, J. Advances in Machine Vision Applications for Automatic Inspection and Quality Evaluation of Fruits and Vegetables. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scroccarello, A.; Della Pelle, F.; Rojas, D.; Ferraro, G.; Fratini, E.; Gaggiotti, S.; Cichelli, A.; Compagnone, D. Metal nanoparticles based lab-on-paper for phenolic compounds evaluation with no sample pretreatment. Application to extra virgin olive oil samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1183, 338971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.K.; Kar, A.; Jha, S.N.; Khan, M.A. Machine vision system: A tool for quality inspection of food and agricultural products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. Materials and Product Design, 3rd ed.; GRANTA Teaching Resources: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, C.T. Umbrella Diagram: 1981–2021, five decades of forecasts and CMF design. Color Cult. Sci. J. 2021, 13, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grum, F.; Witzel, R.F.; Stensby, P. Evaluation of Whiteness. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1974, 64, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrolstad, R.E.; Smith, D.E. Color Analysis. In Food Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE EN ISO/CIE 11664-4:2020; Colorimetry—Part 4: CIE 1976 L*a*b* Colour Space. CIE—Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage: Vienna, Austria, 2007.

- Schlapfer, K. Farbmeytik in der Reproduktionstechnik und im Mehrfarbendruck; UGRA: Gallen, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nollet, L.M.L.; Toldrà, F. Handbook of Dairy Foods Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780333227794. [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga, S.; Nishi, S.; Ohtera, R. Measurement and Estimation of Spectral Sensitivity Functions for Mobile Phone Cameras. Sensors 2021, 21, 4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umapathi, R.; Sonwal, S.; Lee, M.J.; Mohana Rani, G.; Lee, E.-S.; Jeon, T.-J.; Kang, S.-M.; Oh, M.-H.; Huh, Y.S. Colorimetric based on-site sensing strategies for the rapid detection of pesticides in agricultural foods: New horizons, perspectives, and challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, J.; You, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, L. Colorimetric detection of heavy metal ions with various chromogenic materials: Strategies and applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedalwafa, M.A.; Li, Y.; Ni, C.; Wang, L. Colorimetric sensor arrays for the detection and identification of antibiotics. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 2836–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafabakhsh, M.; Dadmehr, M.; Kazemi Noureini, S.; Es’haghi, Z.; Malekkiani, M.; Hosseini, M. Paper-based colorimetric detection of COVID-19 using aptasenor based on biomimetic peroxidase like activity of ChF/ZnO/CNT nano-hybrid. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 301, 122980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbach, S.; Jiang, N.; Moreddu, R.; Dong, X.; Kurz, W.; Wang, C.; Dong, J.; Yin, Y.; Butt, H.; Brischwein, M.; et al. Smartphone-based colorimetric detection system for portable health tracking. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 4361–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, M.E.; Mutlu, A.Y.; Alankus, G.; Kılıç, V.; Bayram, A.; Horzum, N. Quantifying colorimetric tests using a smartphone app based on machine learning classifiers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kap, Ö.; Kılıç, V.; Hardy, J.G.; Horzum, N. Smartphone-based colorimetric detection systems for glucose monitoring in the diagnosis and management of diabetes. Analyst 2021, 146, 2784–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Koh, Y.G.; Lee, W. Smartphone-based colorimetric analysis of structural colors from pH-responsive photonic gel. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 345, 130359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, M.; Sprowls, M.; Jackemeyer, D.; Long, M.; Perez, I.D.; Maret, W.; Chen, F.; Tao, N.; Forzani, E. Total iron measurement in human serum with a smartphone. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2020, 8, 2800309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkaynak, D.; Treibitz, T.; Xiao, B.; Gürkan, U.A.; Allen, J.J.; Demirci, U.; Hanlon, R.T. Use of commercial off-the-shelf digital cameras for scientific data acquisition and scene-specific color calibration. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2014, 31, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Eriksson, M. Classification and quantitative optical analysis of liquid and solid samples using a mobile phone as illumination source and detector. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 185, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M. Small camera as a handheld colorimetric tool in the analytical chemistry. Chem. Pap. 2017, 71, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Ni, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mao, X.; Wang, S. A fine recognition method of strawberry ripeness combining Mask R-CNN and region segmentation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1211830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Pi, J.; Xia, L. A novel and high precision tomato maturity recognition algorithm based on multi-level deep residual network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 9403–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhang, G. Digital image colorimetry on smartphone for chemical analysis: A review. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2021, 171, 108829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, T.B.; Costa, A.G.; da Silva, T.R.; Paes, J.L.; de Oliveira, M.V.M. Tomato quality based on colorimetric characteristics of digital images. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. E Ambient. 2020, 24, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanov, P.V.; Divin, A.G.; Egorov, A.S.; Yudaev, V.A. Mechatronic system for fruit and vegetables sorting. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 734, 012128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trémea, A.; Schettini, R.; Tominaga, S. Computational Color Imaging, Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop, CCIW 2015, Saint Etienne, France, 24–26 March 2015; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Image Processing, Computer Vision, Pattern Recognition, and Graphics (LNIP); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9016, pp. 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- User Guide of Gray White Balance Colour Card. Available online: https://gwbcolourcard.uk/assets/userguide.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- X-Rite User Manual-ColorChecker Passport. Available online: https://www.xrite.com/-/media/xrite/files/manuals_and_userguides/c/o/colorcheckerpassport_user_manual_en.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Pascale, D. RGB Coordinates of the Macbeth ColorChecker; The BabelColor Company: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2006; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Soda, Y.; Bakker, E. Quantification of Colorimetric Data for Paper-Based Analytical Devices. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 3093–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darktable Darktable 4.2 User Manual. Available online: https://docs.darktable.org/usermanual/4.2/en/darktable_user_manual.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Rigacci, N. The Gray Ehite Balance Colour Card: An X-Rite Clone. Available online: https://www.rigacci.org/wiki/doku.php/doc/appunti/software/colorchecker_clones (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Hoenk, M.E.; Jewell, A.D.; Kyne, G.; Hennessy, J.; Jones, T.; Shapiro, C.; Bush, N.; Nikzad, S.; Morris, D.; Lawrie, K.; et al. Surface Passivation by Quantum Exclusion: On the Quantum Efficiency and Stability of Delta-Doped CCDs and CMOS Image Sensors in Space. Sensors 2023, 23, 9857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patch Number | Color | L* (D65) | a* (D65) | b* (D65) | Patch Number | Color | L* (D65) | a* (D65) | b* (D65) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 87.94 | −0.99 | −0.04 | 13 | 60.93 | 28.15 | 54.69 | ||

| 2 | 75.60 | −0.48 | 1.28 | 14 | 50.67 | 6.37 | −25.98 | ||

| 3 | 64.67 | −0.23 | 1.83 | 15 | 55.58 | 43.61 | 9.48 | ||

| 4 | 52.72 | 0.05 | 2.40 | 16 | 40.14 | 26.48 | −24.01 | ||

| 5 | 38.69 | 0.20 | 2.35 | 17 | 73.17 | −19.15 | 67.30 | ||

| 6 | 20.74 | −0.25 | −0.25 | 18 | 71.85 | 10.14 | 68.58 | ||

| 7 | 37.81 | 1.19 | −34.60 | 19 | 44.17 | 5.91 | 12.19 | ||

| 8 | 60.42 | −40.63 | 46.58 | 20 | 71.95 | 16.00 | 18.43 | ||

| 9 | 45.34 | 52.23 | 34.65 | 21 | 58.62 | −5.23 | −15.72 | ||

| 10 | 80.11 | −2.12 | 79.36 | 22 | 50.25 | −18.23 | 37.78 | ||

| 11 | 55.82 | 40.49 | −9.44 | 23 | 61.97 | 4.01 | −19.33 | ||

| 12 | 59.01 | −30.36 | −18.14 | 24 | 70.33 | −27.61 | 8.86 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | R | G | B | ΔEConv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 34.46 | 3.43 | 11.51 | 93 | 79 | 63 | 0.37 | 0.79 |

| B | 67.00 | 1.50 | 9.87 | 173 | 162 | 145 | 0.60 | 0.71 |

| C | 59.57 | 1.67 | 4.42 | 150 | 143 | 136 | 0.26 | 0.74 |

| D | 89.96 | 0.91 | 2.35 | 230 | 225 | 222 | 0.40 | 0.68 |

| E | 85.71 | 0.72 | 4.19 | 219 | 213 | 207 | 0.19 | 0.69 |

| F | 85.96 | 6.53 | 31.08 | 248 | 209 | 157 | 0.21 | 0.66 |

| G | 85.41 | 3.64 | 22.94 | 237 | 210 | 170 | 0.40 | 0.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giurlani, W.; Meoli, A.; Marseglia, M.; Bonini, M. Smartphones as Portable Tools for Reliable Color Determination of Metal Coatings Using a Colorimetric Calibration Card. Coatings 2025, 15, 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121411

Giurlani W, Meoli A, Marseglia M, Bonini M. Smartphones as Portable Tools for Reliable Color Determination of Metal Coatings Using a Colorimetric Calibration Card. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121411

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiurlani, Walter, Arianna Meoli, Marco Marseglia, and Massimo Bonini. 2025. "Smartphones as Portable Tools for Reliable Color Determination of Metal Coatings Using a Colorimetric Calibration Card" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121411

APA StyleGiurlani, W., Meoli, A., Marseglia, M., & Bonini, M. (2025). Smartphones as Portable Tools for Reliable Color Determination of Metal Coatings Using a Colorimetric Calibration Card. Coatings, 15(12), 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121411