Electrical, Thermal, Flexural, and EMI-Shielding Properties of Epoxy-Based Polymer Composites Reinforced with RGO/AgRGO Spray-Coated Carbon Fibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

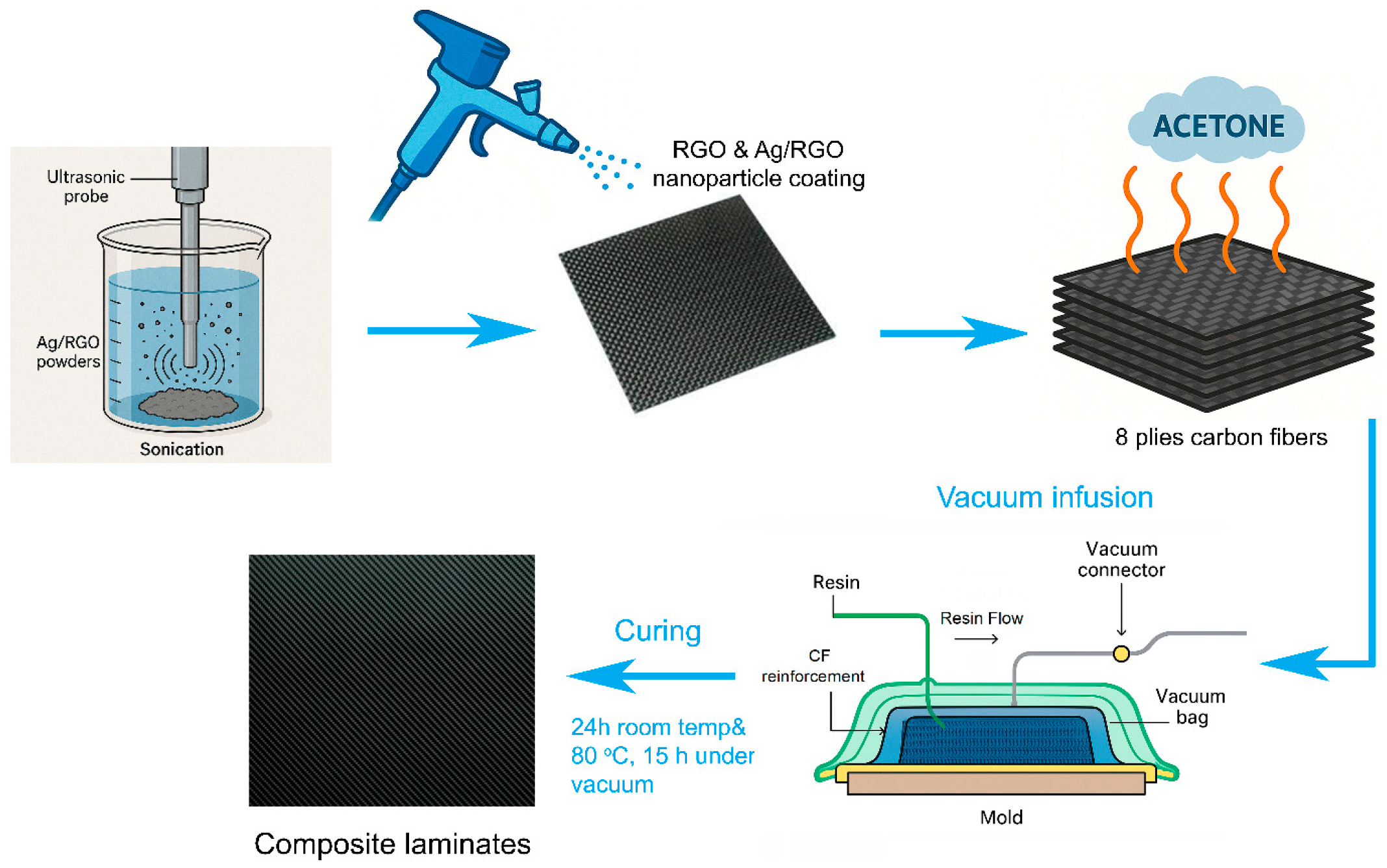

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of AgRGO Powders

2.3. Fabrication of Coated CF Composites

2.4. Testing and Characterization

3. Results and Discussions

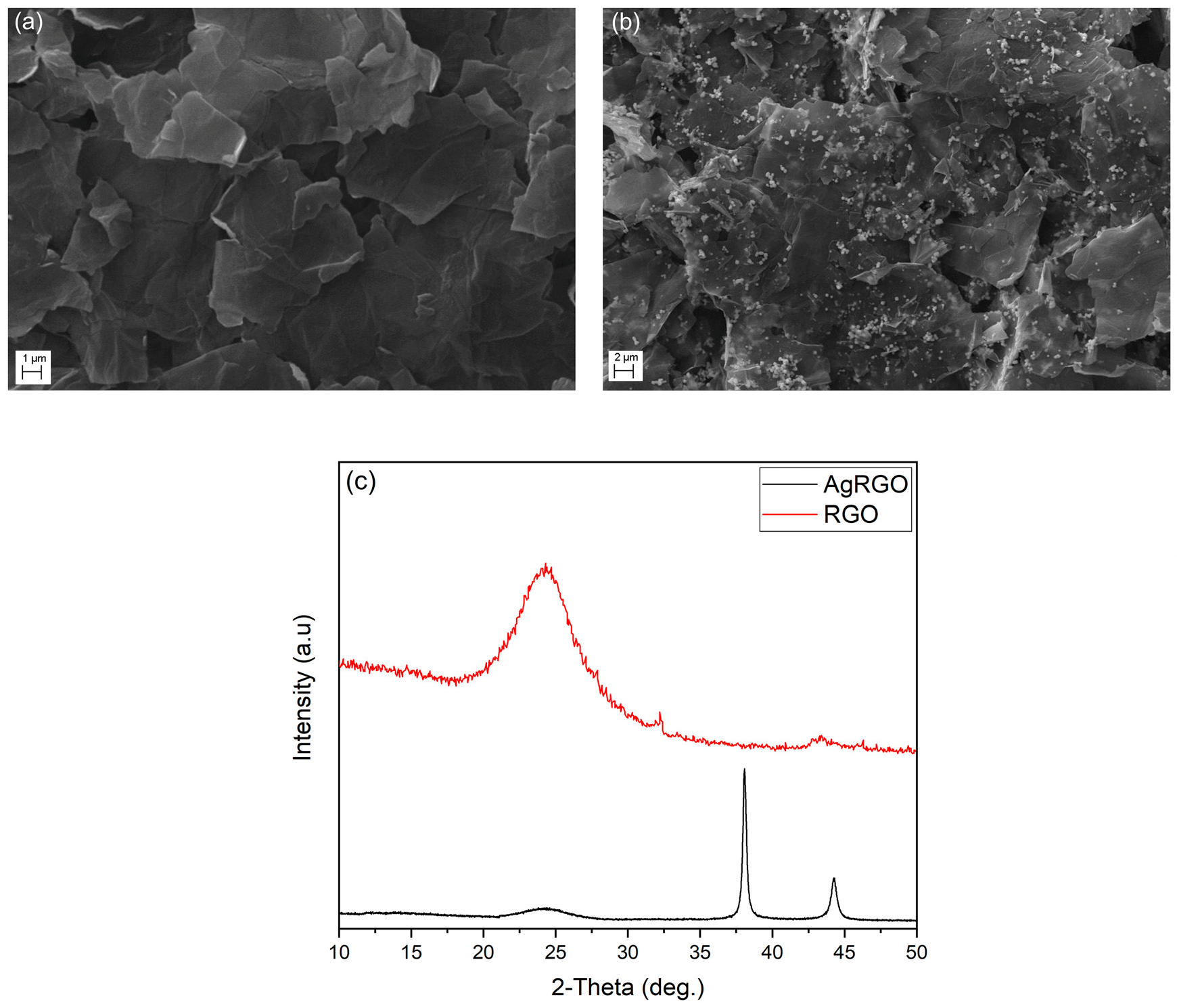

3.1. Morphology and Phase Analysis of Fillers

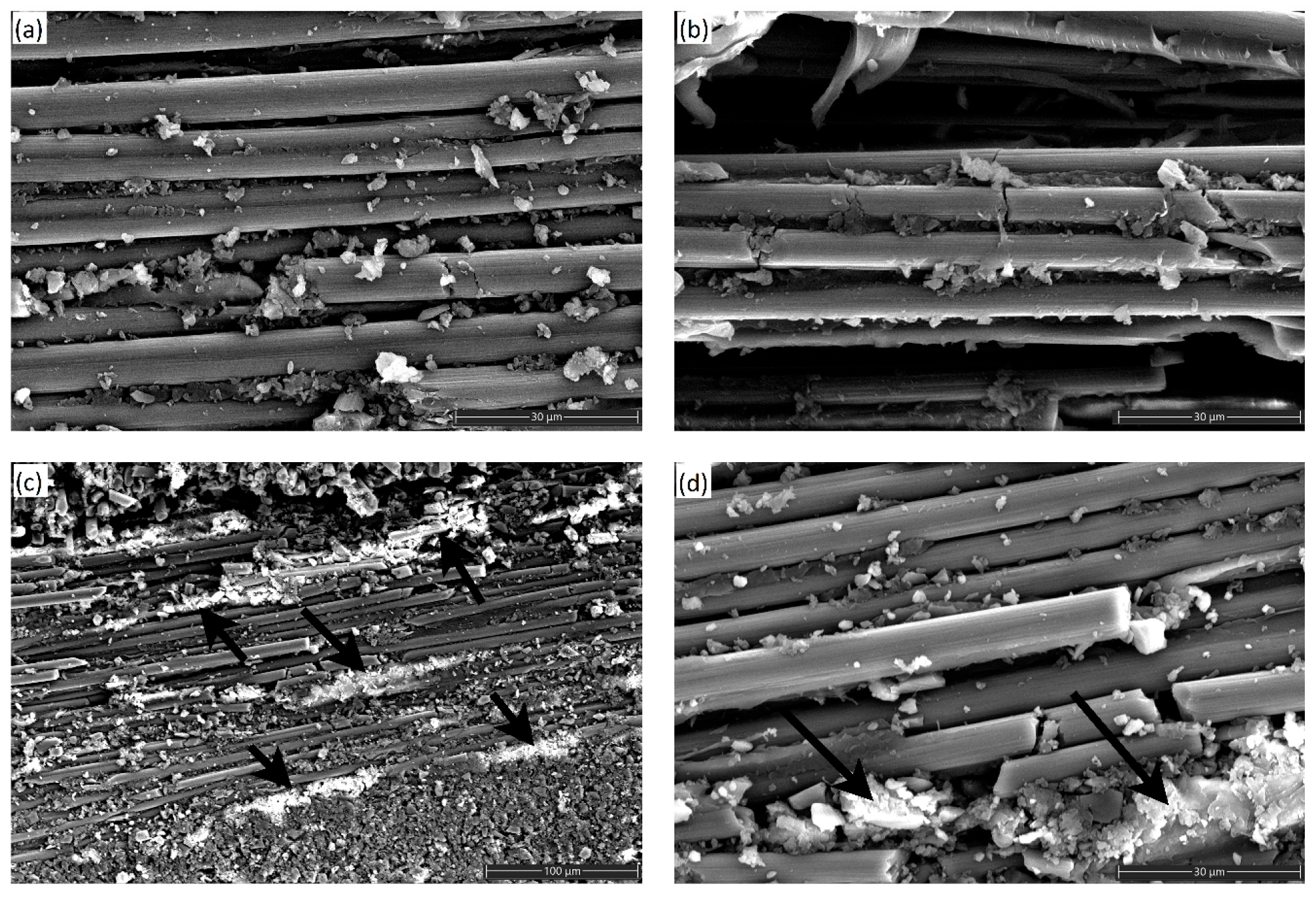

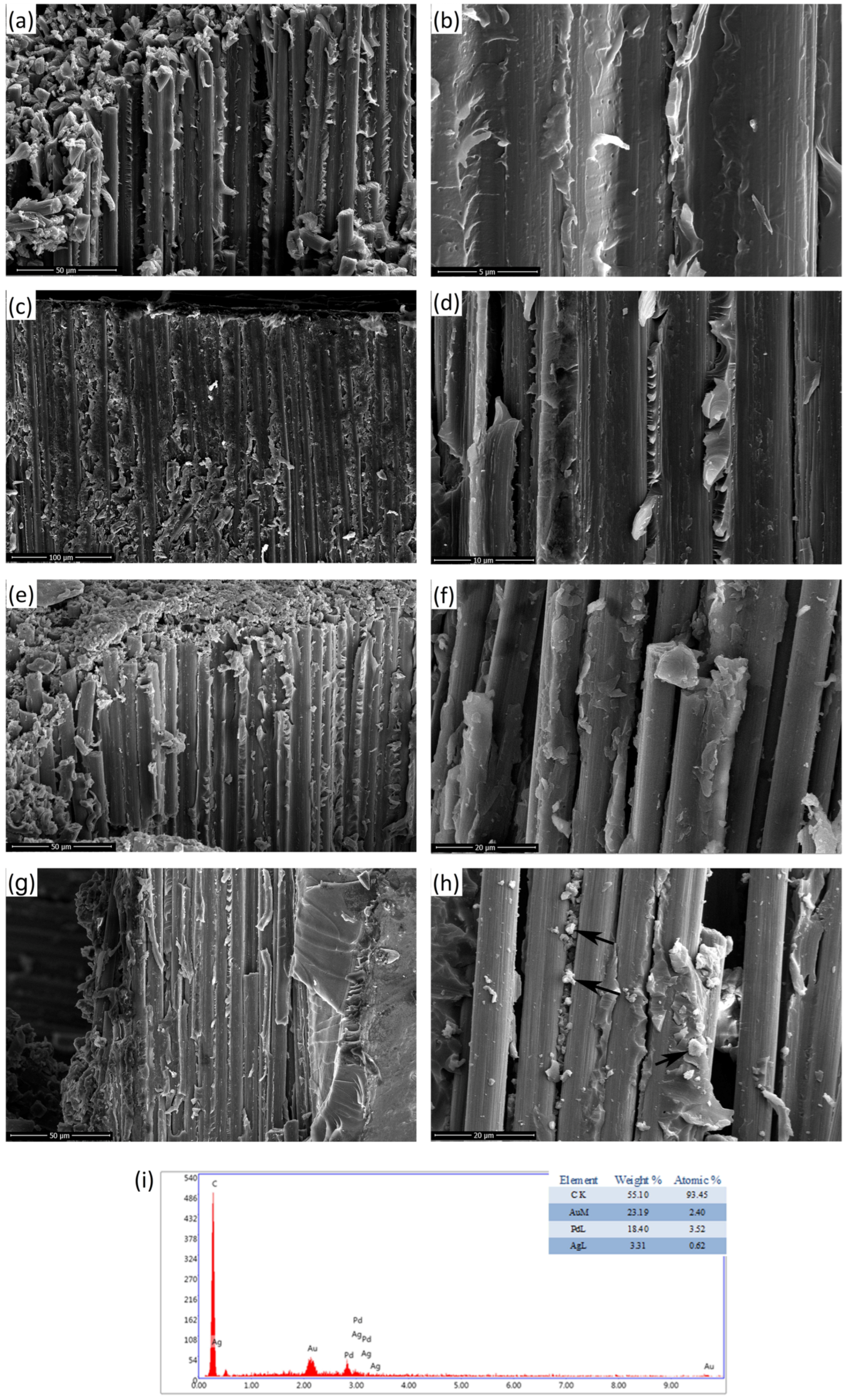

3.2. Microstructural Examination of Composites

3.3. Electrical Conductivity Properties

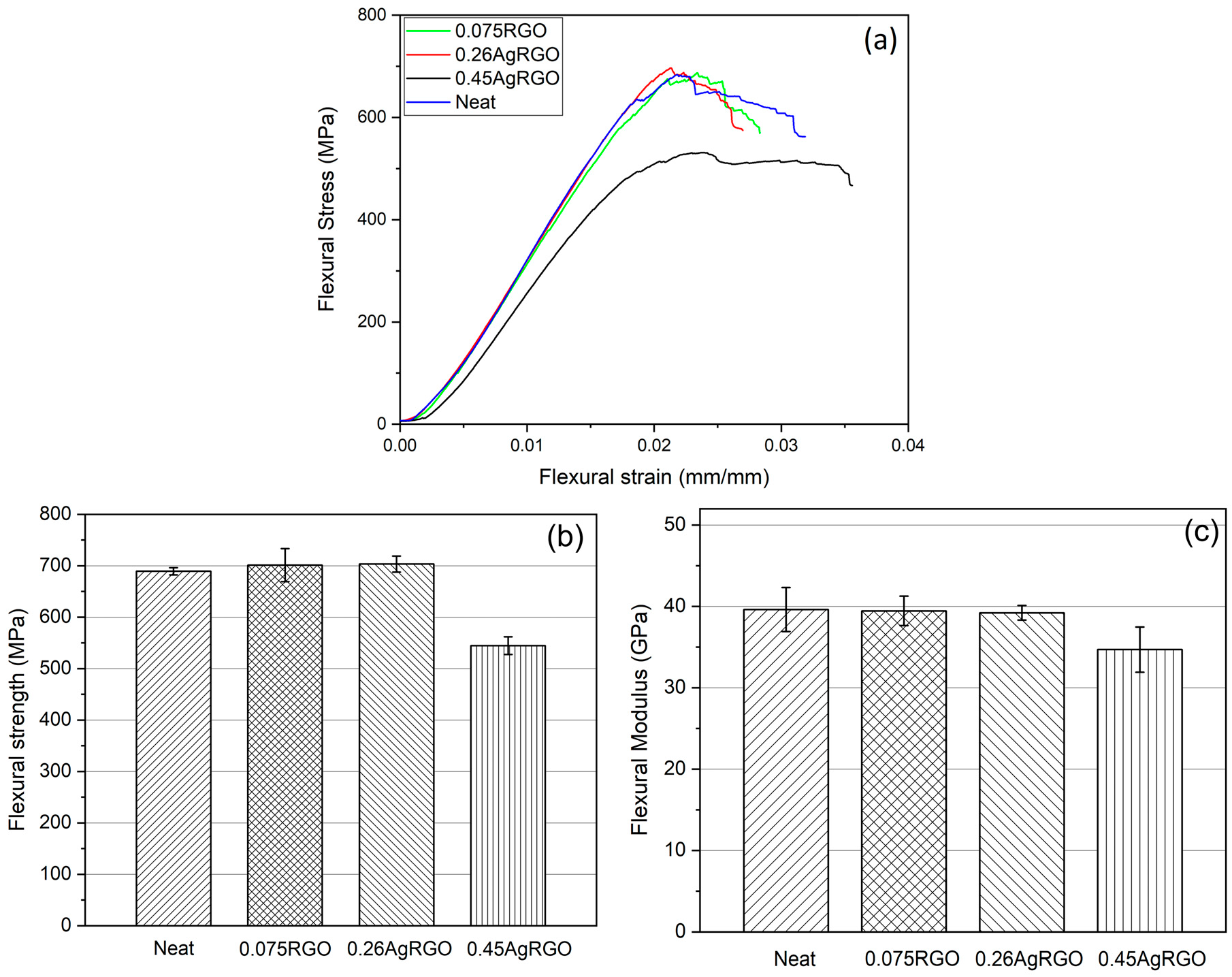

3.4. Flexural Properties

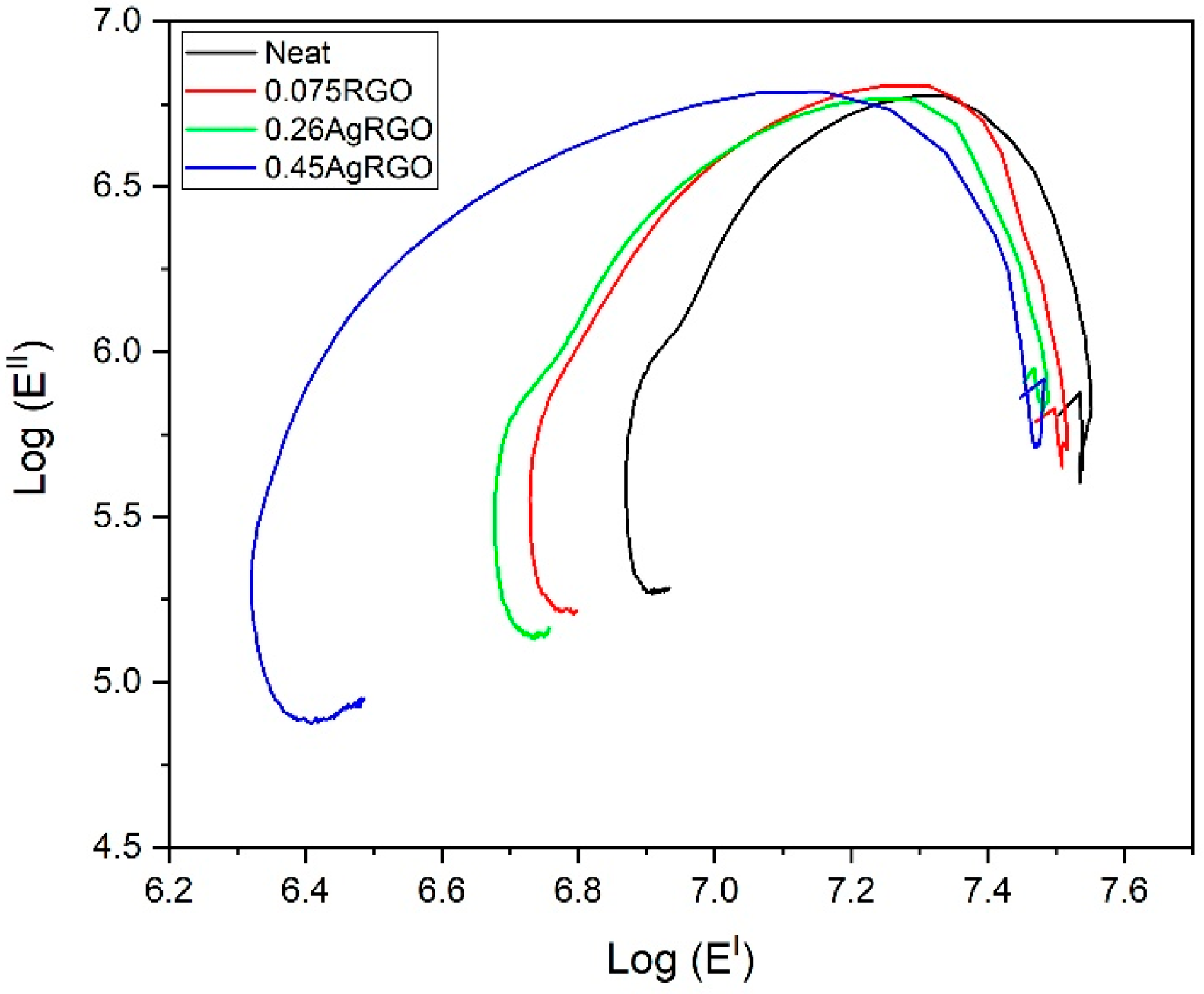

3.5. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

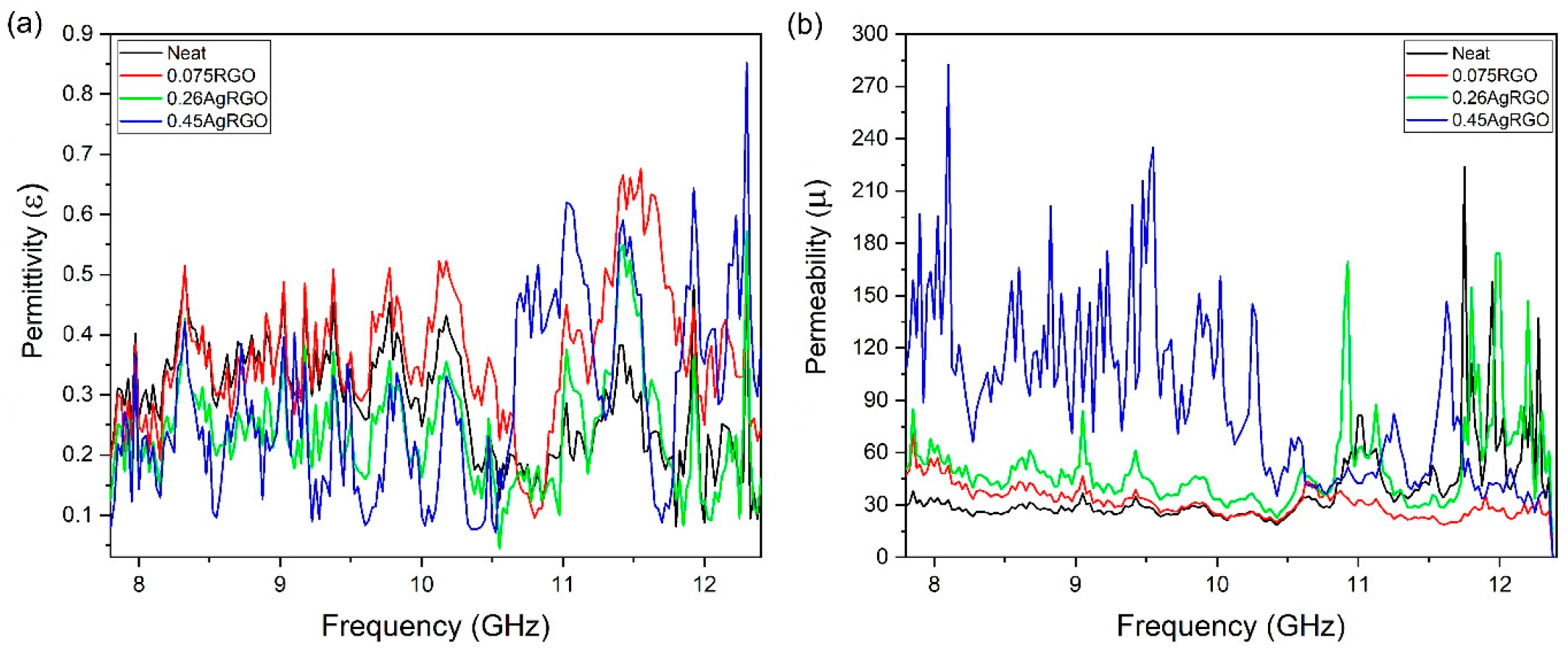

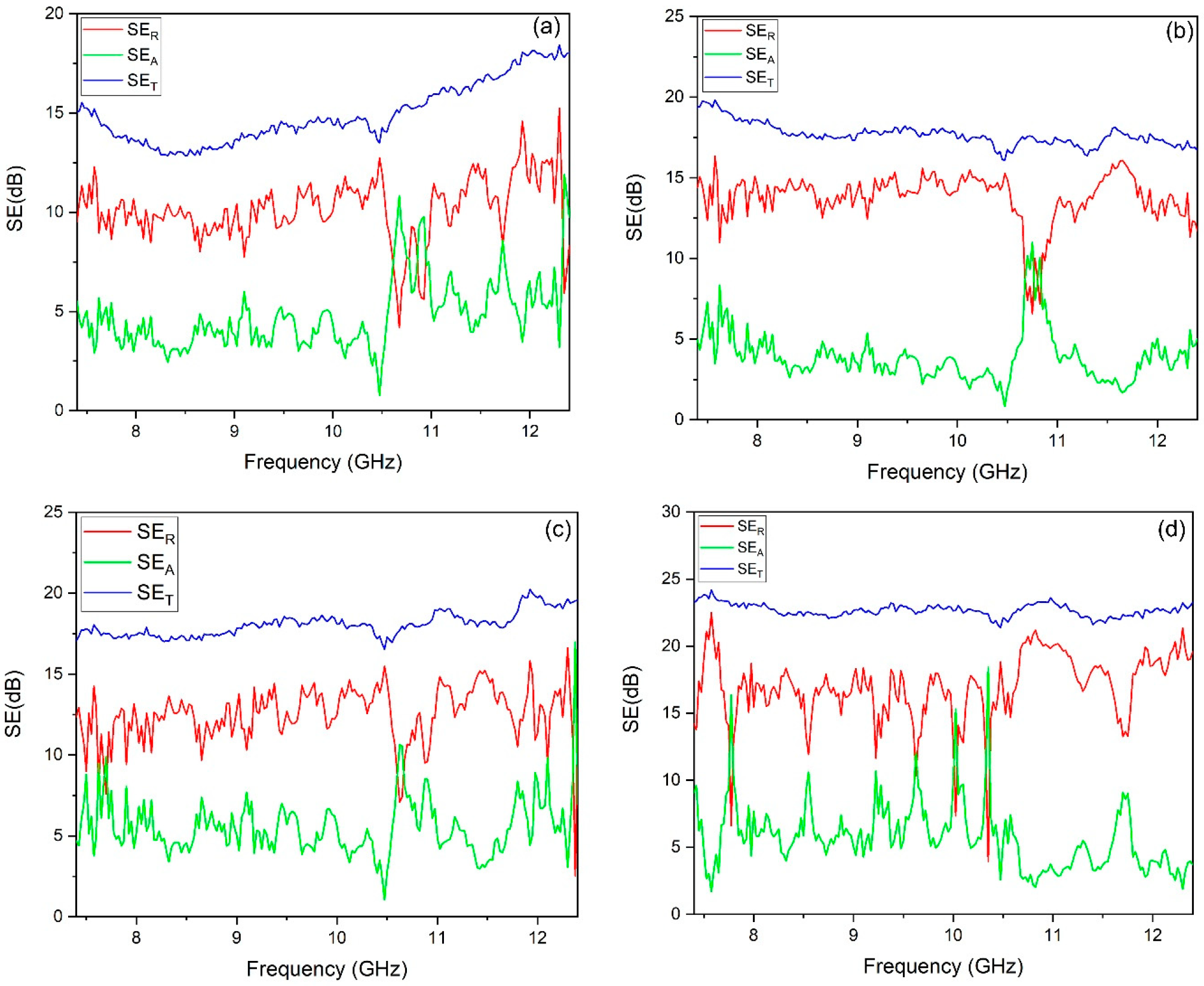

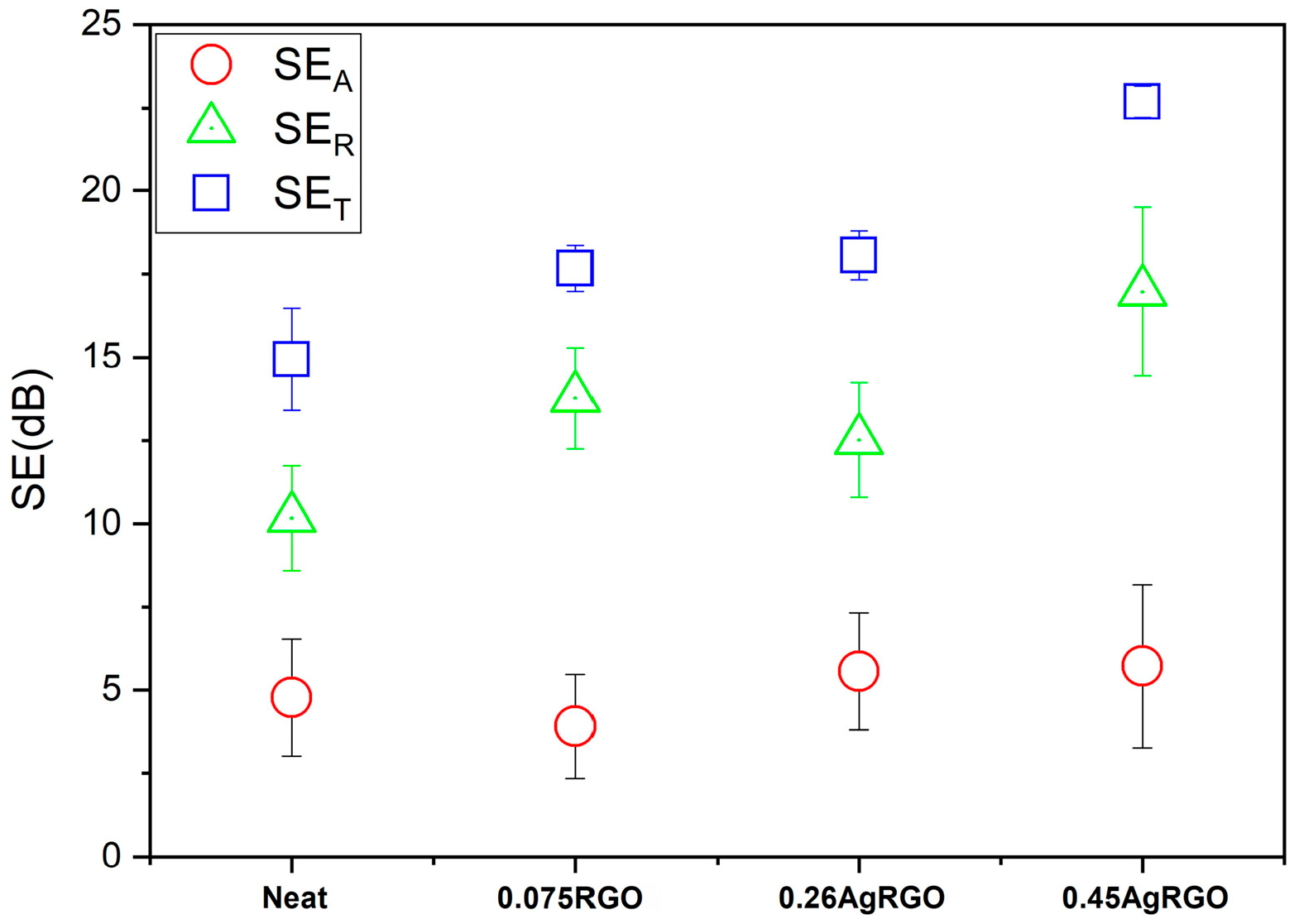

3.6. Dielectric Properties and EMI Shielding Efficiency

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Everson, K.; Akbar, A.K.; Sanghyun, Y.; Ruoyu, W.; Jun, M.; Philippe, O.; Nathalie, G.; Chun, H.W. Improving the through-thickness thermal and electrical conductivity of carbon fibre/epoxy laminates by exploiting synergy between graphene and silver nano-inclusions. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 69, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, E.C.; Silva, R.A.; Pardini, L.C.; Rezende, M.C. A review on the development and properties of continuous fiber/epoxy/aluminum hybrid composites for aircraft structures. Mater. Res. 2006, 9, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argon, A.; Cohen, R. Toughenability of polymers. Polymer 2003, 44, 6013–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutis, C. Fibre reinforced composites in aircraft construction. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2005, 41, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostagiannakopoulou, C.; Loutas, T.H.; Sotiriadis, G.; Markou, A.; Kostopoulos, V. On the interlaminar fracture toughness of carbon fiber composites enhanced with graphene nano-species. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015, 118, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftelen—Odabaşı, H.; Odabaşı, A.; Özdemir, M.; Baydoğan, M. A study on graphene reinforced carbon fiber epoxy composites: Investigation of electrical, flexural, and dynamic mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftelen-Odabaşı, H.; Ruiz-Perez, F.; Odabaşı, A.; Helhel, S.; López-Estrada, S.M.; Caballero-Briones, F. EMI-shielding response of GO/Fe3O4/polypyrrole(PPy)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) composites. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 55, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, H.B.; Tambe, P.; Joshi, G.M. Influence of covalent and non-covalent modification of graphene on the mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of epoxy/graphene nanocomposites: A review. Compos. Interfaces 2018, 25, 381–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschoppe, K.; Beckert, F.; Beckert, M.; Mülhaupt, R. Thermally reduced graphite oxide and mechanochemically functionalized graphene as functional fillers for epoxy nanocomposites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2015, 300, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, W.; Xiao, C.; Wei, M. Effects of different amine-functionalized graphene on the mechanical, thermal, and tribological properties of polyimide nanocomposites synthesized by in situ polymerization. Polymer 2018, 140, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyugüzel, T.; Mecitoğlu, Z.; Kaftelen-Odabaşı, H. Experimental and numerical investigation on the mode I and mode II interlaminar fracture toughness of nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide reinforced composites. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 128, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Gupta, V.; Yerramalli, C.S.; Singh, A. Flexural strength enhancement in carbon-fiber epoxy composites through graphene nano-platelets coating on fibers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 179, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, Z.; Peijs, T.; Bilotti, E. Synergistic effects of spray-coated hybrid carbon nanoparticles for enhanced electrical and thermal surface conductivity of CFRP laminates. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 105, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.Y.; Lau, K.T.; Fox, B.; Hameed, N.; Lee, J.H.; Hui, D. Surface modification of carbon fibre using graphene–related materials for multifunctional composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 133, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanar, D.E.; Kaftelen—Odabaşı, H.; İtik, M. Production and Performance Evaluation of a Novel Ionic Electroactive Polymer Actuator With Ag/RGO Electrodes. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 13935–13945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthi, D.K.; Khabashesku, V.N.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Blaine, J.; Yarlagadda, S.; Roseman, D.; Barrera, E.V. Carbon fiber–bismaleimide composites filled with nickel-coated single-walled carbon nanotubes for lightning-strike protection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 2527–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummers, W.S., Jr.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, F.N.S.; Hayashi, K.; Komori, Y.; Suga, Y.; Asahara, N. Research in the application of the VaRTM technique to the fabrication of primary aircraft composite structures, Mitsubishi. Heavy Ind. Ltd. Tech. Rev. 2005, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, K.A.; Shivakumar, K.N. Graphene-modified carbon/epoxy nanocomposites: Electrical, thermal and mechanical properties. J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 53, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftelen-Odabaşı, H.; Odabaşı, A.; Caballero-Briones, F.; Arvizu-Rodriguez, L.E.; Özdemir, M.; Baydoğan, M. Effects of polyvinylpyrrolidone as a dispersant agent of reduced graphene oxide on the properties of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2023, 42, 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D790; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1997.

- ASTM D4065; Standard Practice for Plastics: Dynamic Mechanical Properties: Determination and Report of Procedures. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Bashir, M.A. Use of dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) for characterizing interfacial interactions in filled polymers. Solids 2021, 2, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, A.M.; Ross, G.F. Measurement of the intrinsic properties of materials by time-domain techniques. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1970, 19, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Wang, Q.; Xu, D.; Liu, P. Microwave assisted sinter molding of polyetherimide/carbon nanotubes composites with segregated structure for high-performance EMI shielding applications. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 182, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgueras, L.D.C.; Alves, M.A.; Rezende, M.C. Dielectric properties of microwave absorbing sheets produced with silicone and polyaniline. Mater. Res. 2010, 13, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, I.J.; Park, S.J. Influence of Ag-doped graphene on electrochemical behaviors and specific capacitance of polypyrrole-based nanocomposites. Synth. Met. 2010, 160, 2355–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.J.; Xu, Z.; Tang, B.L.; Dang, C.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Zeng, X.L.; Lin, B.C.; Shen, X.J. The effect of graphene oxide modified short carbon fiber on the interlaminar shear strength of carbon fiber fabric/epoxy composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagotia, N.; Sharma, D.K. Systematic study of dynamic mechanical and thermal properties of multiwalled carbon nanotube reinforced polycarbonate/ethylene methylacrylate nanocomposites. Polym. Test. 2019, 73, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madarvoni, S.; Rama, S.P.S. Dynamic mechanical behaviour of graphene, hexagonal boron nitride reinforced carbon-Kevlar, hybrid fabric-based epoxy nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | RGO Content (w/w%) | AgRGO Content (w/w%) | Ag/RGO Ratio (in wt.) | T-T-T Conductivity (S/m) (×10−3) | Surface Conductivity (S/m) (×10−3) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat | 0 | 0 | - | 1.98 ± 0.09 | 1.78 ± 0.17 | Present |

| 0.075 RGO | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0 | 2.41 ± 0.06 | 2.53 ± 0.07 | Present |

| 0.26 AgRGO | 0.075 | 0.26 | 2.5 | 78.05 ± 0.06 | 72.50 ± 0.05 | Present |

| 0.45 AgRGO | 0.075 | 0.45 | 5 | 273.31 ± 0.2 | 256.07 ± 0.3 | Present |

| 0.25 GNP | 0.25 | - | 145 | 134 | [6] | |

| 1.25 GNP | 1.25 | - | 239 | 234 | [6] | |

| GNPs/CFRP | 1 | - | 1.31 | - | [19] | |

| RGO | 0.15 | - | 469 | 218.6 | [20] |

| Sample Name | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strain at Maximum Load (%) | Flexural Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neat | 689 ± 7.1 | 2.35 ± 0.11 | 39.6 ± 2.6 |

| 0.075 RGO | 701 ± 32 | 2.31 ± 0.12 | 39.4 ± 1.8 |

| 0.26 AgRGO | 703 ± 15 | 2.13 ± 0.09 | 39.2 ± 0.8 |

| 0.45 AgRGO | 545 ± 17 | 2.53 ± 0.04 | 34.7 ± 2.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaftelen Odabaşı, H. Electrical, Thermal, Flexural, and EMI-Shielding Properties of Epoxy-Based Polymer Composites Reinforced with RGO/AgRGO Spray-Coated Carbon Fibers. Coatings 2025, 15, 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121404

Kaftelen Odabaşı H. Electrical, Thermal, Flexural, and EMI-Shielding Properties of Epoxy-Based Polymer Composites Reinforced with RGO/AgRGO Spray-Coated Carbon Fibers. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121404

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaftelen Odabaşı, Hülya. 2025. "Electrical, Thermal, Flexural, and EMI-Shielding Properties of Epoxy-Based Polymer Composites Reinforced with RGO/AgRGO Spray-Coated Carbon Fibers" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121404

APA StyleKaftelen Odabaşı, H. (2025). Electrical, Thermal, Flexural, and EMI-Shielding Properties of Epoxy-Based Polymer Composites Reinforced with RGO/AgRGO Spray-Coated Carbon Fibers. Coatings, 15(12), 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121404