Effect of Cobalt Content on the Microstructures and Electrochemical Performances of Cobalt-Based Prussian Blue Electrodes in a Sea Water Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

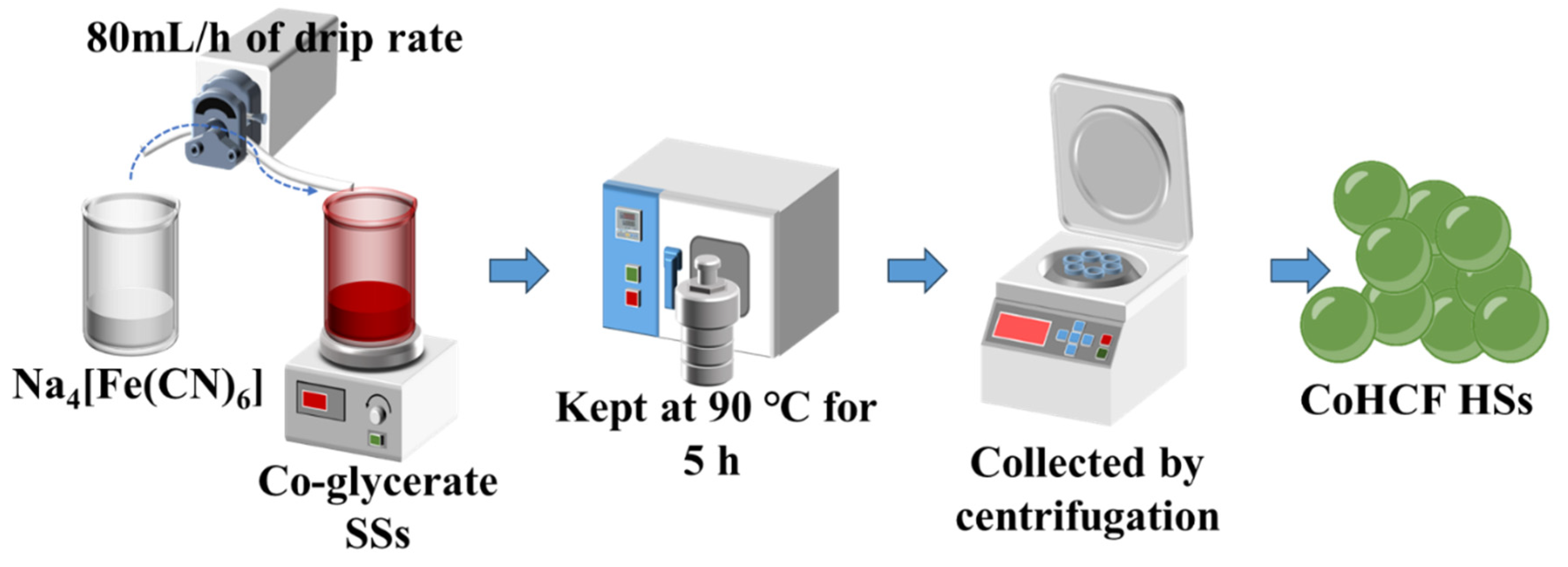

2.1. Synthesis of CoHCF HSs

2.2. Structure Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

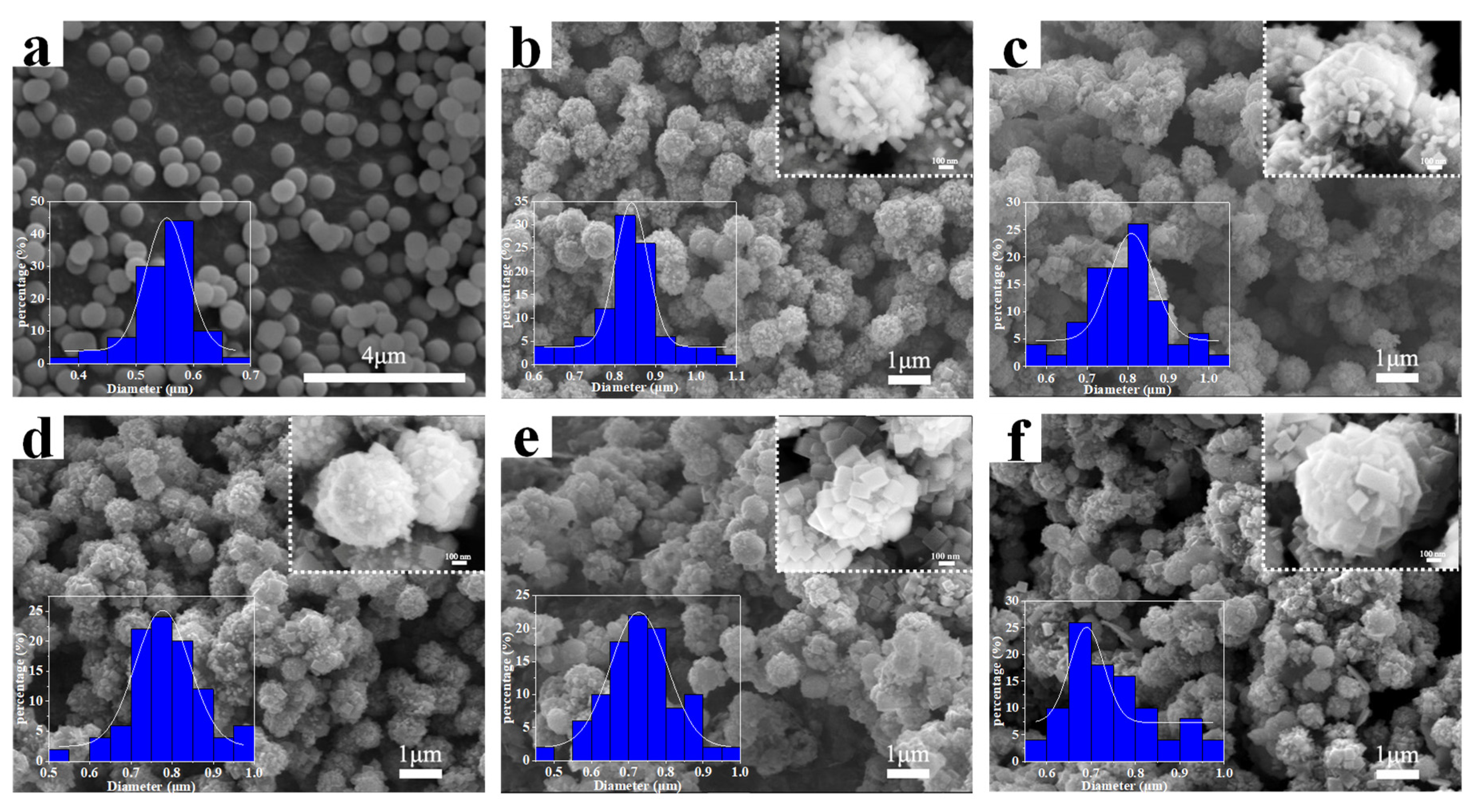

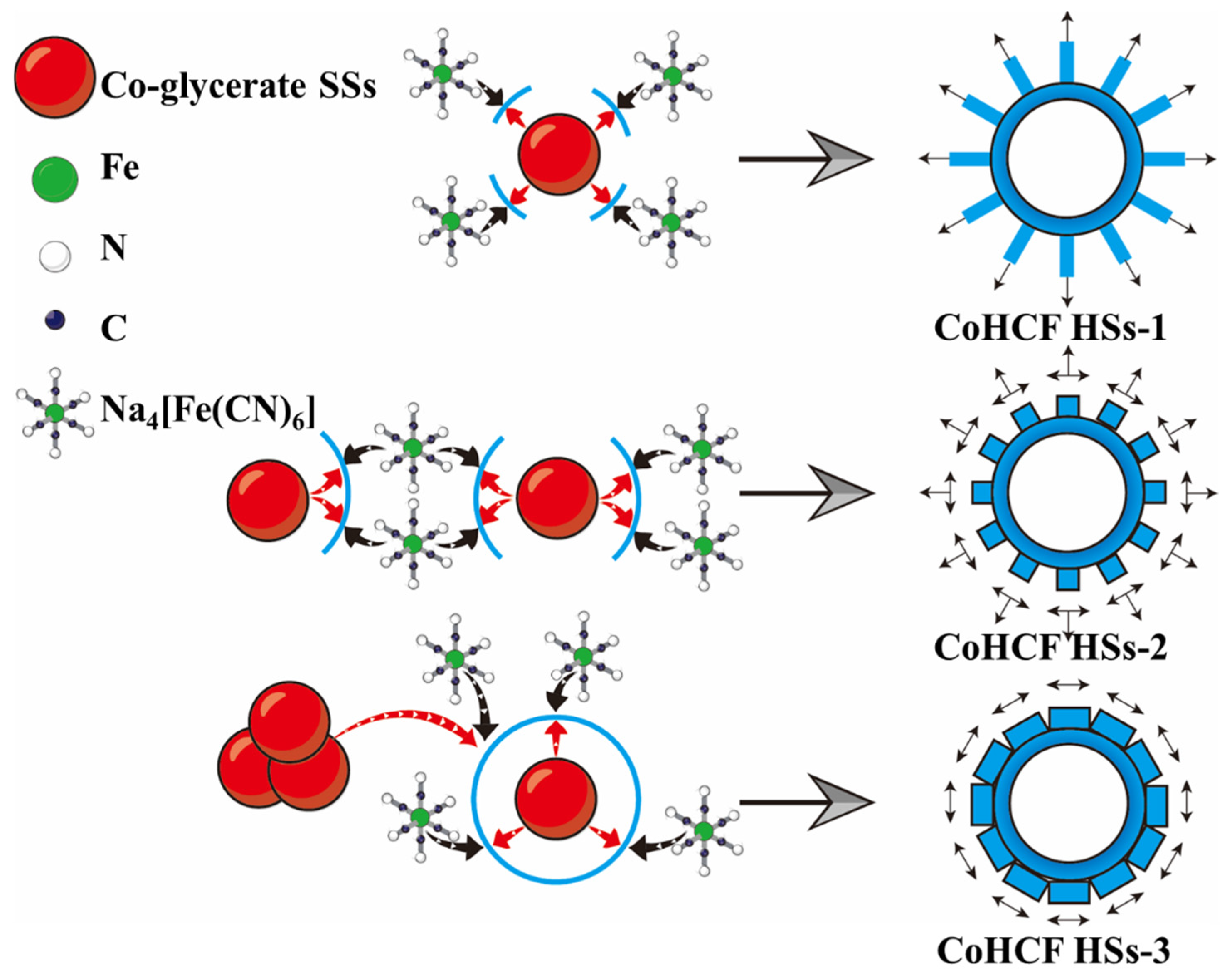

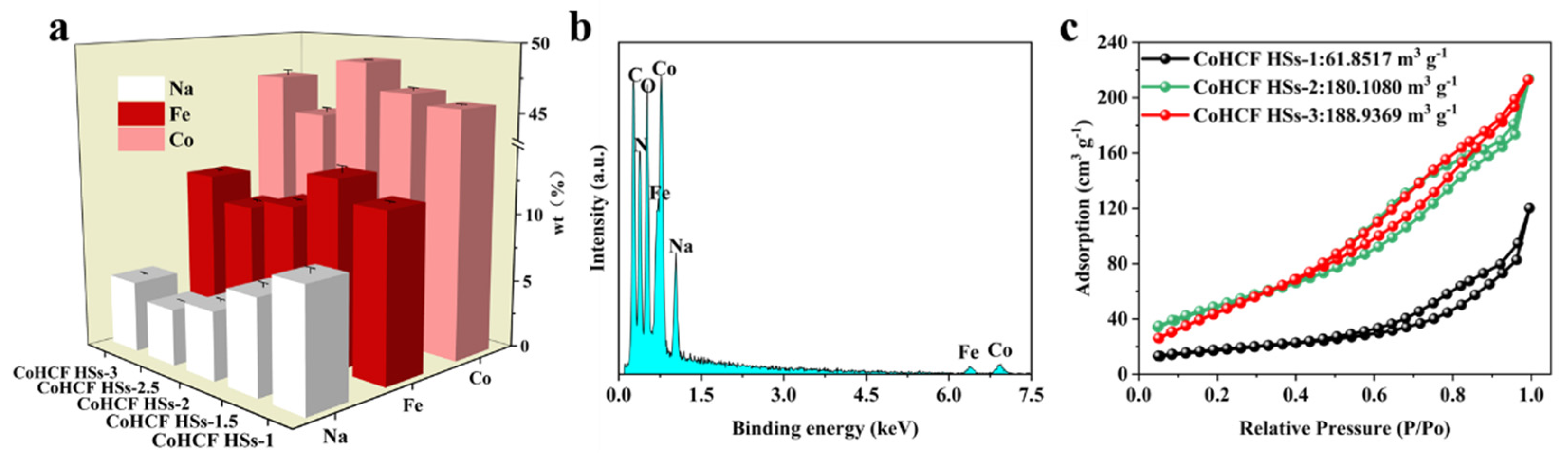

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.K.; Mueller, F.; Kim, H.; Bresser, D.; Park, J.S.; Lim, D.H.; Kim, G.T.; Passerini, S.; Kim, Y. Rechargeable-hybrid-seawater fuel cell. NPG Asia Mater. 2014, 6, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.M.; Park, J.S.; Kim, Y.; Go, W.; Han, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. Rechargeable seawater batteries-from concept to applications. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Bu, L.; Wang, W. Investigations on the discharge/charge process of a novel AgCl/Ag/carbon felt composite electrode used for seawater batteries. J. Power Sources 2021, 506, 230210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, S.T.; Go, W.; Han, J.; Thuy, L.P.T.; Kishor, K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. Emergence of rechargeable seawater batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 22803–22825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, B.Q.; Zhao, C.X.; Zhang, Q. Seawater electrolyte-based metal–air batteries: From strategies to applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3253–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tian, X. Progress of seawater batteries: From mechanisms, materials to applications. J. Power Sources 2024, 617, 235161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Gao, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Chou, S. Prussian Blue Analogues for Aqueous Sodium-Ion Batteries: Progress and Commercialization Assessment. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2401984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Z.; Li, W.; Dang, Q.; Jing, C.; Zhang, W.; Chu, J.; Tang, L.; Hu, M. A high-power seawater battery working in a wide temperature range enabled by an ultra-stable Prussian blue analogue cathode. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 8685–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.M.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, W. A battery-supercapacitor hybrid energy storage device that directly uses seawater or saltwater lake water. Mater. Today Adv. 2024, 24, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, G.; Sharma, M.; Tripathi, S.K. Prussian blue analogue as cathode materials in sodium ion batteries: A review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 126, 116995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.; Lin, H.; Meng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Su, Y.; Hang, X.; Pang, H. Self-template synthesis of PBA/MOF hollow nanocubes for aqueous battery. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 155618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, B.; Mu, P.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Shi, Y.; Fu, J.; Zheng, H.; Tang, M. Fabricating 3D Network for FeP@ MXene toward Stable and High-Capacity Lithium-Ion Storage. Small Methods 2025, 9, 2500185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wu, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Effect of doping Ni on microstructures and properties of CoxNi1-xHCF based seawater battery. Vacuum 2024, 220, 112822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Wu, X.L.; Yin, Y.X.; Guo, Y.G. High-quality Prussian blue crystals as superior cathode materials for room-temperature sodium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1643–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yi, S.H.; Li, L.; Chun, S.E. Enhanced stability and rate performance of zinc-doped cobalt hexacyanoferrate (CoZnHCF) by the limited crystal growth and reduced distortion. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 69, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, H.; Song, J.; Yin, C.; Xu, H. Hierarchical mesoporous octahedral K 2 Mn 1− x Co x Fe (CN) 6 as a superior cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 16205–16212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Xu, E.; Zhu, H.; Chang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, Z.; Yu, D.; Jiang, Y. A Ni-doping-induced phase transition and electron evolution in cobalt hexacyanoferrate as a stable cathode for sodium-ion batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 2491–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, X.; Kubota, K.; Hosaka, T.; Chihara, K.; Komaba, S. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of Na-rich Prussian blue analogues containing Mn, Fe, Co, and Fe for Na-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 378, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, A.; Zhu, Z.; Chai, L.; Ding, J.; Zhong, L.; Li, T.T.; Hu, Y.; Qian, J.; Huang, S. Surfactant-Mediated Morphological Evolution of MnCo Prussian Blue Structures. Small 2020, 16, 2004614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornamehr, B.; Presser, V.; Zarbin, A.J.; Yamauchi, Y.; Husmann, S. Prussian blue and its analogues as functional template materials: Control of derived structure compositions and morphologies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 10473–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Lu, X.F.; Zhang, S.L.; Luan, D.; Li, S.; Lou, X.W. Construction of Co–Mn Prussian blue analog hollow spheres for efficient aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22189–22194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczynski, G.; Hultman, L. Reliable determination of chemical state in x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy based on sample-work-function referencing to adventitious carbon: Resolving the myth of apparent constant binding energy of the C 1s peak. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 451, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczynski, G.; Hultman, L. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Towards reliable binding energy referencing. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 107, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.J.; Edmund, C.M.; Shang, C.; Guo, Z. Nucleation and growth in solution synthesis of nanostructures–from fundamentals to advanced applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 123, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Zhao, A.; Zhong, F.; Feng, X.; Chen, W.; Qian, J.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y. A low-defect and Na-enriched Prussian blue lattice with ultralong cycle life for sodium-ion battery cathode. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 332, 135533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Xie, H.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, S.; Wang, C.; Yu, Z.; Chu, W.; Song, L.; Wei, S. Stepwise hollow Prussian blue nanoframes/carbon nanotubes composite film as ultrahigh rate sodium ion cathode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.T.; He, Z.H.; Hou, J.F.; Kong, L.B. Designing CoHCF@ FeHCF Core–Shell Structures to Enhance the Rate Performance and Cycling Stability of Sodium-Ion Batteries. Small 2023, 19, 2302788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Dou, S.; Chou, S. Low-Cost Zinc Substitution of Iron-Based Prussian Blue Analogs as Long Lifespan Cathode Materials for Fast Charging Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2210725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.H.; Kongvarhodom, C.; Saukani, M.; Yougbaré, S.; Chen, H.M.; Wu, Y.F.; Lin, L.Y. Strategic integration of nickel tellurium oxide and cobalt iron prussian blue analogue into bismuth vanadate for enhanced photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 89, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yang, G.; Jing, M.; Fu, Q.; Chiu, F.C. Microfibrillated cellulose-reinforced bio-based poly (propylene carbonate) with dual shape memory and self-healing properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 20393–20401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; De, R.; Schmidt, H.; Leistenschneider, D.; Ulusoy Ghobadi, T.G.; Oschatz, M.; Karadaş, F.; Dietzek-Ivanšić, B. Probing the Interfacial Molecular Structure of a Co-Prussian Blue In Situ. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 11, 2400009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wan, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, F.; Dong, J.; Yang, W.; Xie, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, F. Catalytic membranes assembled by Co–Fe Prussian blue analogues functionalized graphene oxide nanosheets for rapid removal of contaminants. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 705, 122886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yu, P.; Wong, C.P.; Jiang, C. High-performance stretchable flexible supercapacitor based on lignosulfonate/Prussian blue analogous nanohybrids reinforced rubber by direct laser writing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, P.A.; Ryazantsev, S.V.; Dembitskiy, A.D.; Morozov, A.V.; Das, G.; Aquilanti, G.; Gaboardi, M.; Plaisier, J.R.; Tsirlin, A.A.; Presniakov, I.A.; et al. Unexpected Chain of Redox Events in Co-Based Prussian Blue Analogues. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 3570–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Ju, J.; Pei, L.; Gao, W.; Li, D.; Wang, W.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, Z. Constructing High-Performance Yarn-Shaped Electrodes via Twisting-after-Coating Technique for Weavable Seawater Battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 71038–71047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Polleux, J.; Lim, J.; Dunn, B. Pseudocapacitive contributions to electrochemical energy storage in TiO2 (anatase) nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 14925–14931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanithi, J.; Murugesan, M.; Annamalai, N.; Balu, R.; Shanmugam, K. Enhanced Specific Capacitance and Cycling Stability of Li2Cu2(MoO4)3 of NASICON Family of Supercapacitor Applications. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202403389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Yuan, L.; Li, T.; Shu, C.; Qiao, S.; Dong, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.K.; Dou, S.X.; et al. Nitrogen and oxygen Co-doped porous hard carbon nanospheres with core-shell architecture as anode materials for superior potassium-ion storage. Small 2022, 18, 2104296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Xu, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, W.D.; Manke, I.; Zhou, W.; Peng, X.; Sun, C.; Zhao, K.; Yan, Z.; et al. Dual-function engineering to construct ultra-stable anodes for potassium-ion hybrid capacitors: N, O-doped porous carbon spheres. Nano Energy 2022, 93, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Qian, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, X.; Lin, N.; Qian, Y. Novel bilayer-shelled N, O-doped hollow porous carbon microspheres as high performance anode for potassium-ion hybrid capacitors. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, A.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, B.; Zhang, W.; Li, K. Three-dimensional Prussian blue nanoflower as a high-performance sodium storage electrode for water desalination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 285, 120333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieu, Q.Q.V.; Hoang, H.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Nguyen, V.D.; Le, M.L.P.; Tran, N.H.T.; Kim, I.T.; Nguyen, T.L. Enhancing electrochemical performance of sodium Prussian blue cathodes for sodium-ion batteries via optimizing alkyl carbonate electrolytes. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 30164–30171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mi, C.; Nie, P.; Dong, S.; Tang, S.; Zhang, X. Sodium-rich iron hexacyanoferrate with nickel doping as a high performance cathode for aqueous sodium ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 818, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, E.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Liao, X.Z.; He, Y.; Ma, Z.F. Improved cycling performance of prussian blue cathode for sodium ion batteries by controlling operation voltage range. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 225, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X. Y-tube assisted coprecipitation synthesis of iron-based Prussian blue analogues cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12096–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Song, B.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H. A rechargeable Na-Zn hybrid aqueous battery fabricated with nickel hexacyanoferrate and nanostructured zinc. J. Power Sources 2016, 321, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.M.; Kim, J.; Li, L.; Chun, S.E. Enhanced lifespan and rate capability of cobalt hexacyanoferrate in aqueous Na-ion batteries owing to particle size reduction. J. Power Sources 2023, 556, 232407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wan, J.; Huang, L.; Xu, J.; Ou, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, S.; Fang, C.; Li, Q.; et al. Dual redox-active copper hexacyanoferrate nanosheets as cathode materials for advanced sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 33, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formula | Year | Specific Capacity at Current Density (mAh/g@mA/g) | Electrolyte | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiHCF | 2021 | 57.97@4 (mA cm−2) | East China Sea seawater | [8] |

| Co0.86Ni0.14HCF | 2023 | 76.5@100 | 3.5% NaCl | [13] |

| KCuHCF | 2024 | 66.5@100 | Chinese seawater | [9] |

| Flowerlike PB | 2021 | 72.1@100 | 1M NaCl | [41] |

| NaxFeFe(CN)6 | 2021 | 64.6@100 | 1 M NaClO4 | [42] |

| Na1.74Fe[Fe(CN)6]0.94·3.3H2O | 2018 | 120.4@200 | 1 M NaClO4 | [43] |

| Na1.59Fe[Fe(CN)6]0.95 | 2017 | 100@100 | 1.0 M NaPF6 | [44] |

| Na1.56Fe[Fe(CN)6]0.90·2.42H2O | 2024 | 99.2@70 | 1 M NaClO4 | [45] |

| NiHCF | 2016 | 76.2@100 | 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 50 mM ZnSO4 | [46] |

| Na1.05Co[FeCN)6]0.81·2.68H2O | 2023 | 122@100 | 1 M Na2SO4 | [47] |

| Na2Ni0.2Co0.5Mn0.3Fe(CN)6 | 2020 | 120@8.5 | wt% FEC | [48] |

| NaCo2Fe0.4HCF | - | 121.16@200 | 3.5% NaCl | This article |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Di, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, L. Effect of Cobalt Content on the Microstructures and Electrochemical Performances of Cobalt-Based Prussian Blue Electrodes in a Sea Water Environment. Coatings 2025, 15, 1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121405

Sun C, Di H, Wang R, Wang L. Effect of Cobalt Content on the Microstructures and Electrochemical Performances of Cobalt-Based Prussian Blue Electrodes in a Sea Water Environment. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121405

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chuanpei, Huanyu Di, Rui Wang, and Lianbo Wang. 2025. "Effect of Cobalt Content on the Microstructures and Electrochemical Performances of Cobalt-Based Prussian Blue Electrodes in a Sea Water Environment" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121405

APA StyleSun, C., Di, H., Wang, R., & Wang, L. (2025). Effect of Cobalt Content on the Microstructures and Electrochemical Performances of Cobalt-Based Prussian Blue Electrodes in a Sea Water Environment. Coatings, 15(12), 1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121405