1. Introduction

Premixed mortar, as a pivotal material in modern construction industrialization, has emerged as the predominant trend in building mortar development due to its consistent quality, enhanced construction efficiency, and environmental benefits. However, compared to traditional site-mixed mortar, premixed mortar is required to possess superior workability, stability, and durability to meet the demands of mechanical application and long-term service life. To achieve these performance characteristics, various mineral admixtures and chemical additives are widely employed. Among them, cellulose ether (CE) serves as a crucial water-retaining agent, playing a vital role in determining the comprehensive properties of mortar [

1,

2,

3,

4].

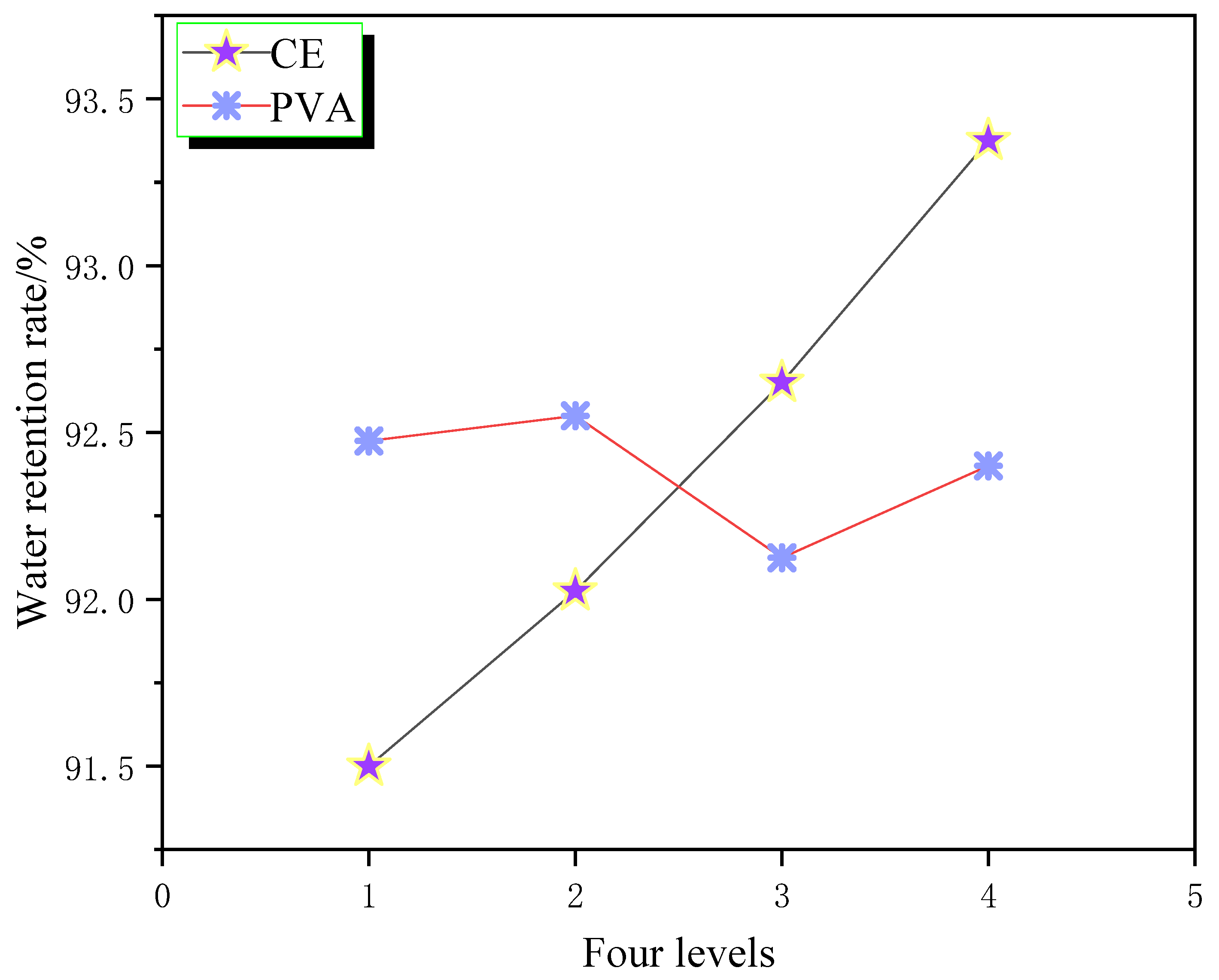

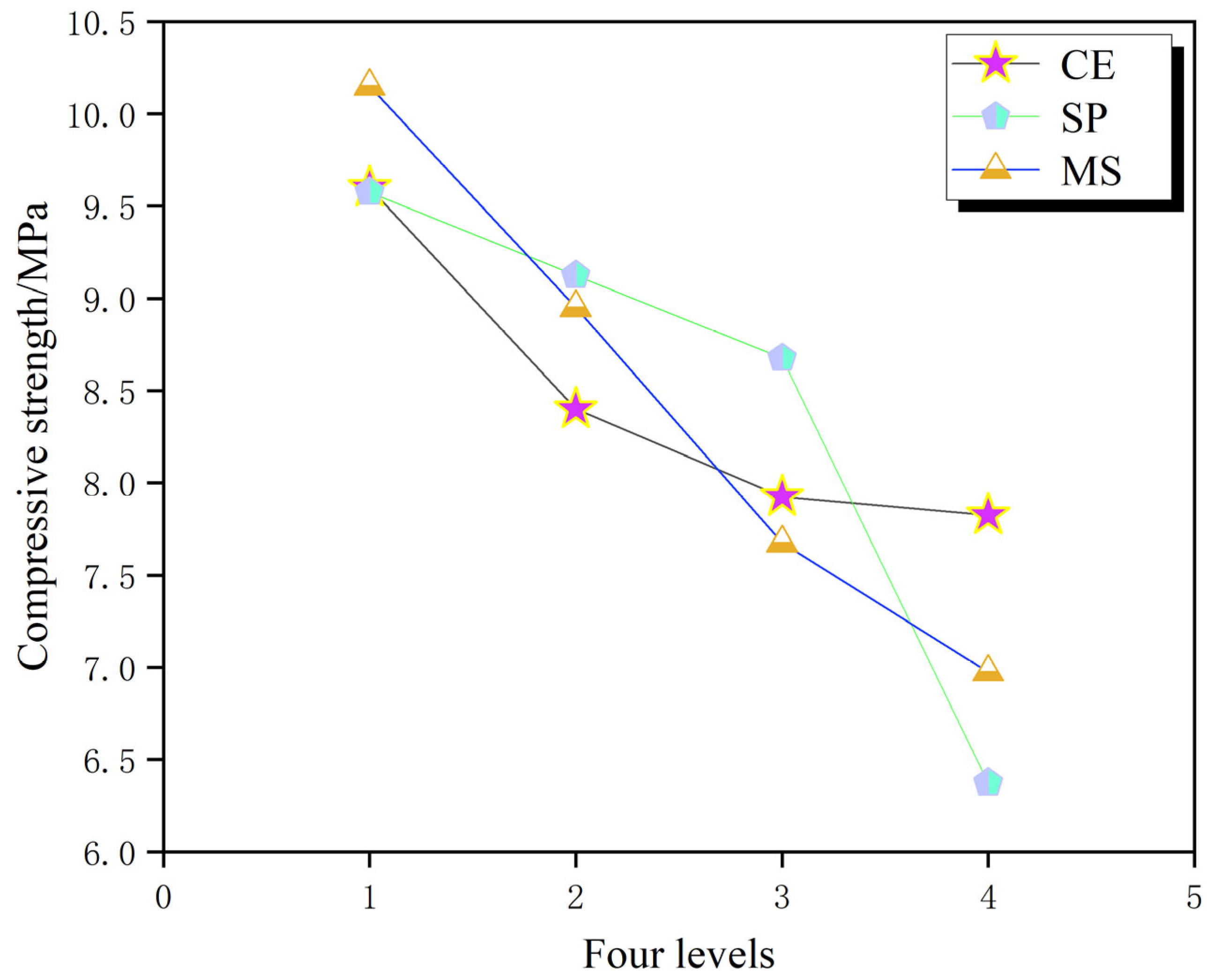

Cellulose ether, a water-soluble polymer obtained by etherifying cellulose, significantly enhances the water retention of mortar. This property prevents premature water evaporation or absorption by the substrate, ensuring the proper hydration of the cement and supporting the normal development of mortar strength [

5]. Moreover, cellulose ether improves the lubrication, viscosity, anti-slump, and overall workability of the mortar. However, studies have shown that while increasing cellulose ether content significantly affects the workability and mechanical properties of mortar, excessive amounts may lead to a decrease in compressive strength and wet density [

6,

7]. This balance between performance enhancements needs to be carefully considered in formulation design.

Similarly to cellulose ether, stone powder, a byproduct of manufactured sand production, can effectively improve the pore structure of mortar through its micro filling effect and pozzolanic activity, enhancing both the compactness and crack resistance of the mortar [

8,

9]. The addition of stone powder not only helps reduce environmental pollution but also partially replaces cement, improving the physical properties of mortar. Additionally, manufactured sand, as an alternative to natural river sand, plays a positive role in improving the mechanical properties of mortar, especially its compressive strength, due to its unique particle shape and grading characteristics [

10].

Furthermore, Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) and bentonite are commonly used admixtures that further enhance mortar performance by reducing plastic shrinkage cracking, improving toughness and crack resistance, and improving water retention and thickening properties [

11,

12,

13]. When combined with cellulose ether, these materials create a synergistic effect, improving the workability of the mortar while enhancing its crack resistance and durability [

14,

15].

Although existing research provides insights into the individual effects of these materials, most studies focus on single-factor influences and fail to comprehensively address the interactions among multiple components. In practical applications, premixed mortars typically contain various admixtures and additives, where complex synergistic effects exist. Consequently, findings from single-factor studies often lack direct applicability for guiding industrial production [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The orthogonal experimental design is an efficient method for investigating multi-factor and multi-level systems. By selecting a representative set of test points, it significantly reduces the number of required experiments while yielding reliable conclusions. For instance, Wang et al. [

21] used an L16(4

3) orthogonal array and showed that tartaric acid (TA) exerted the strongest adverse effect on the flowability of self-leveling mortars, whereas polycarboxylate ether (PCE) and cellulose ether (CE) increased flowability. Brachaczek et al. [

22] applied a Taguchi L8 orthogonal design to evaluate the influence of an air-entraining agent (AEA), cement, polymer additives, cellulose ether and perlite on the air content and porosity of repair mortars, and concluded that AEA dominated air content, while perlite and polymer additives mainly governed porosity, with cement and cellulose ether playing secondary roles. Likewise, Qingxuan Li et al., Junran Liu et al., and Chengbin Yuan et al. similarly utilized a three-factor, three-level orthogonal array design [L9(3

3)] to examine the key factors and their significance levels for different modified mortars [

23,

24,

25]. In contrast to these studies, the present work integrates L16(4

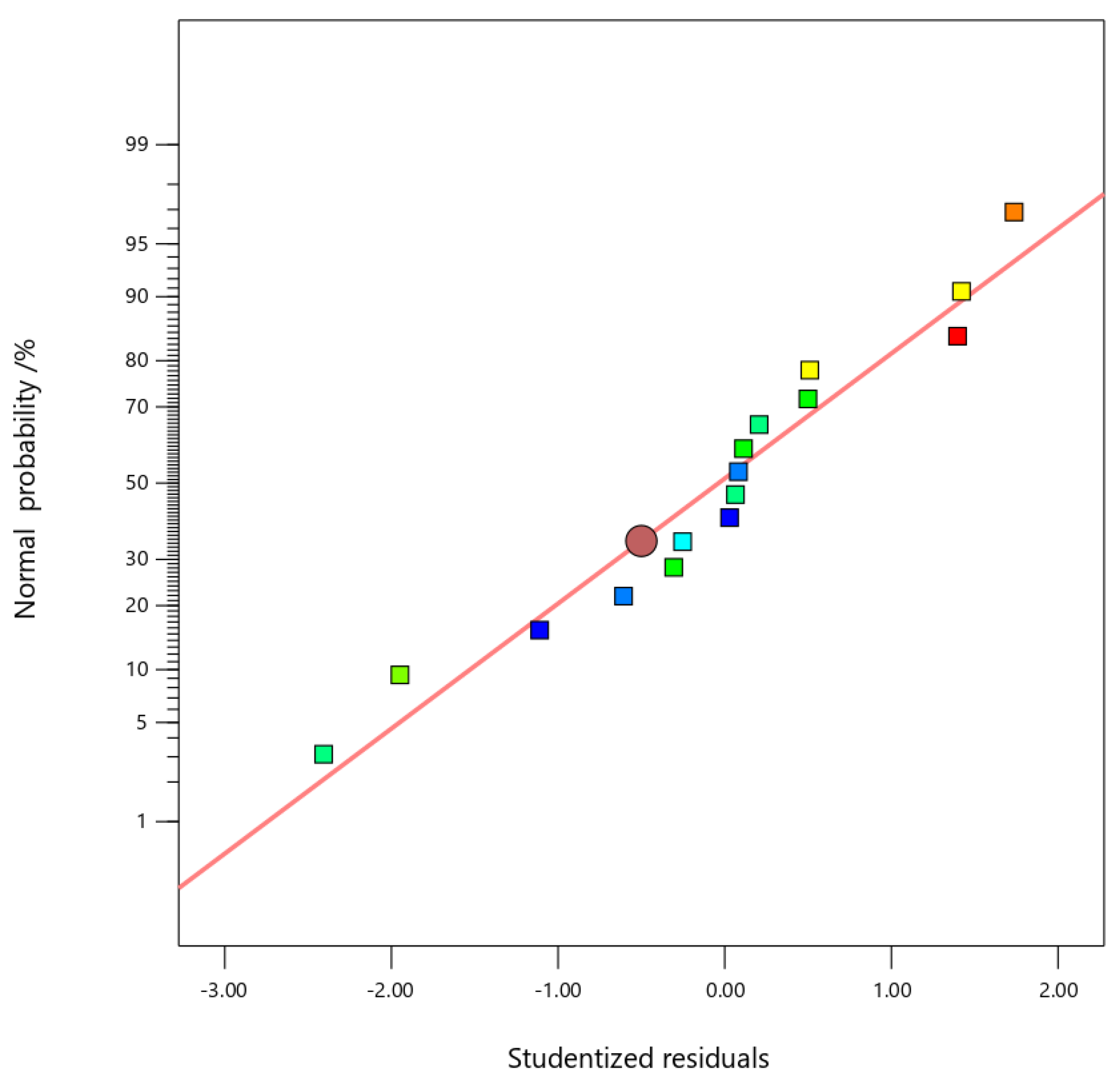

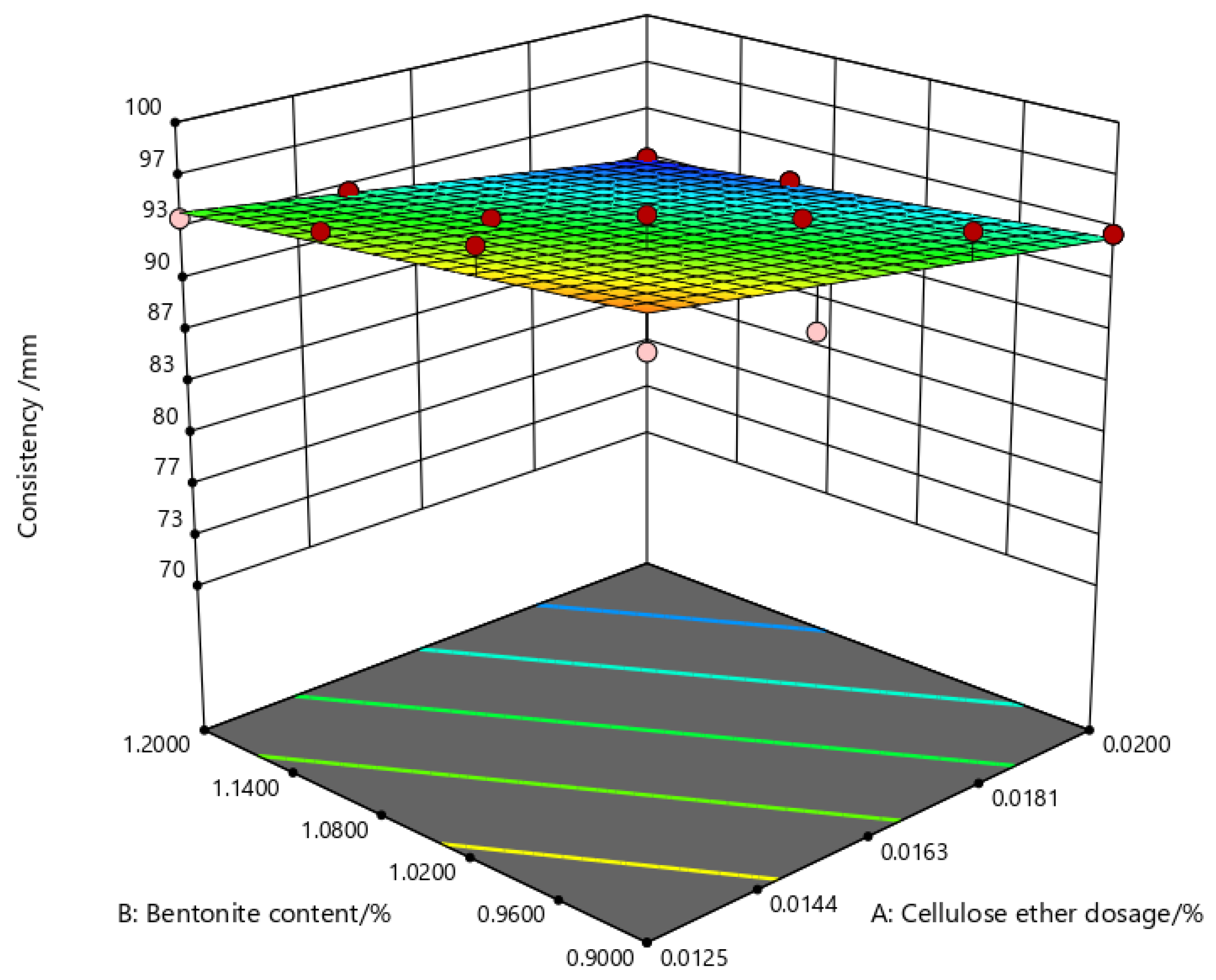

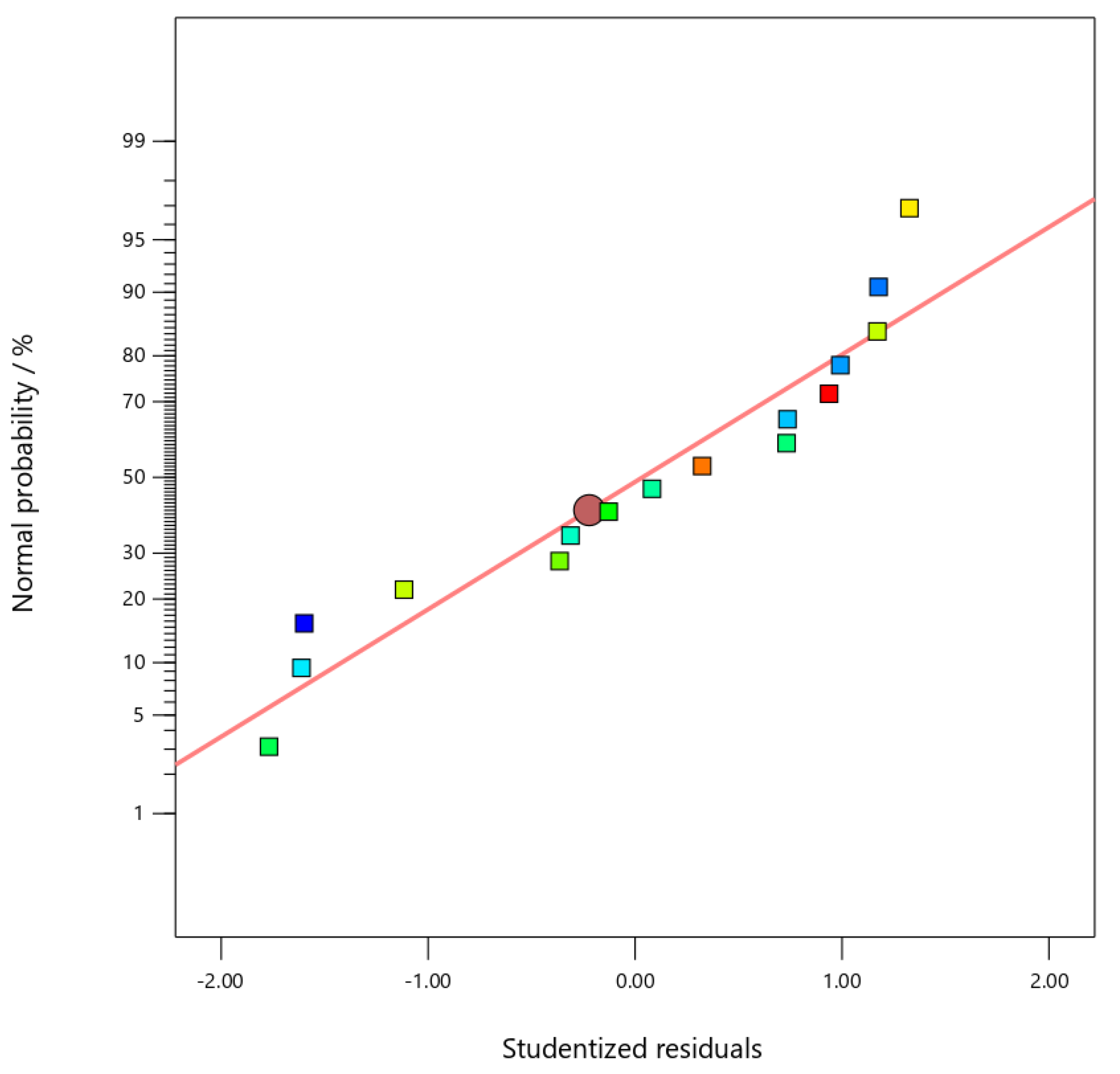

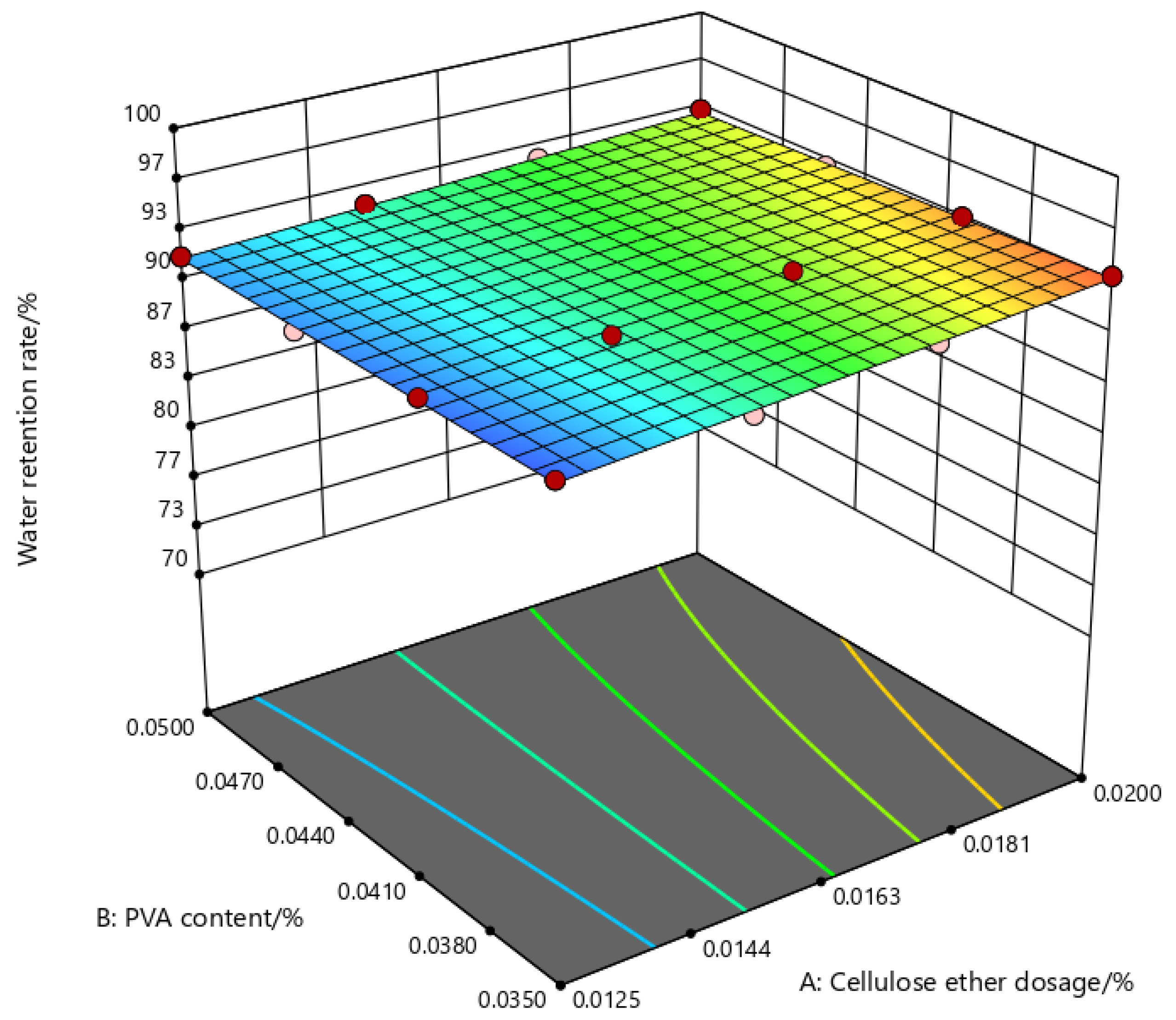

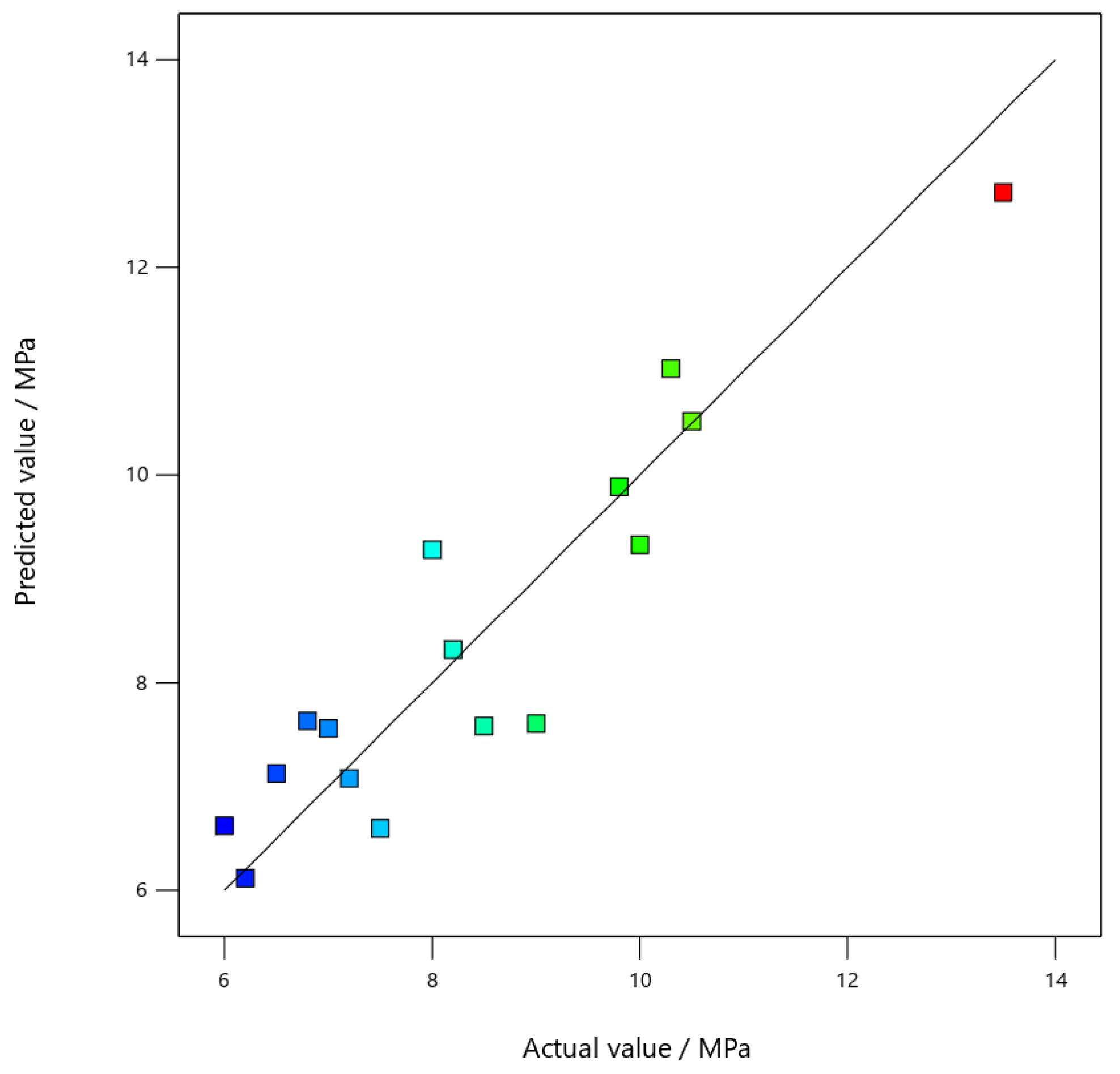

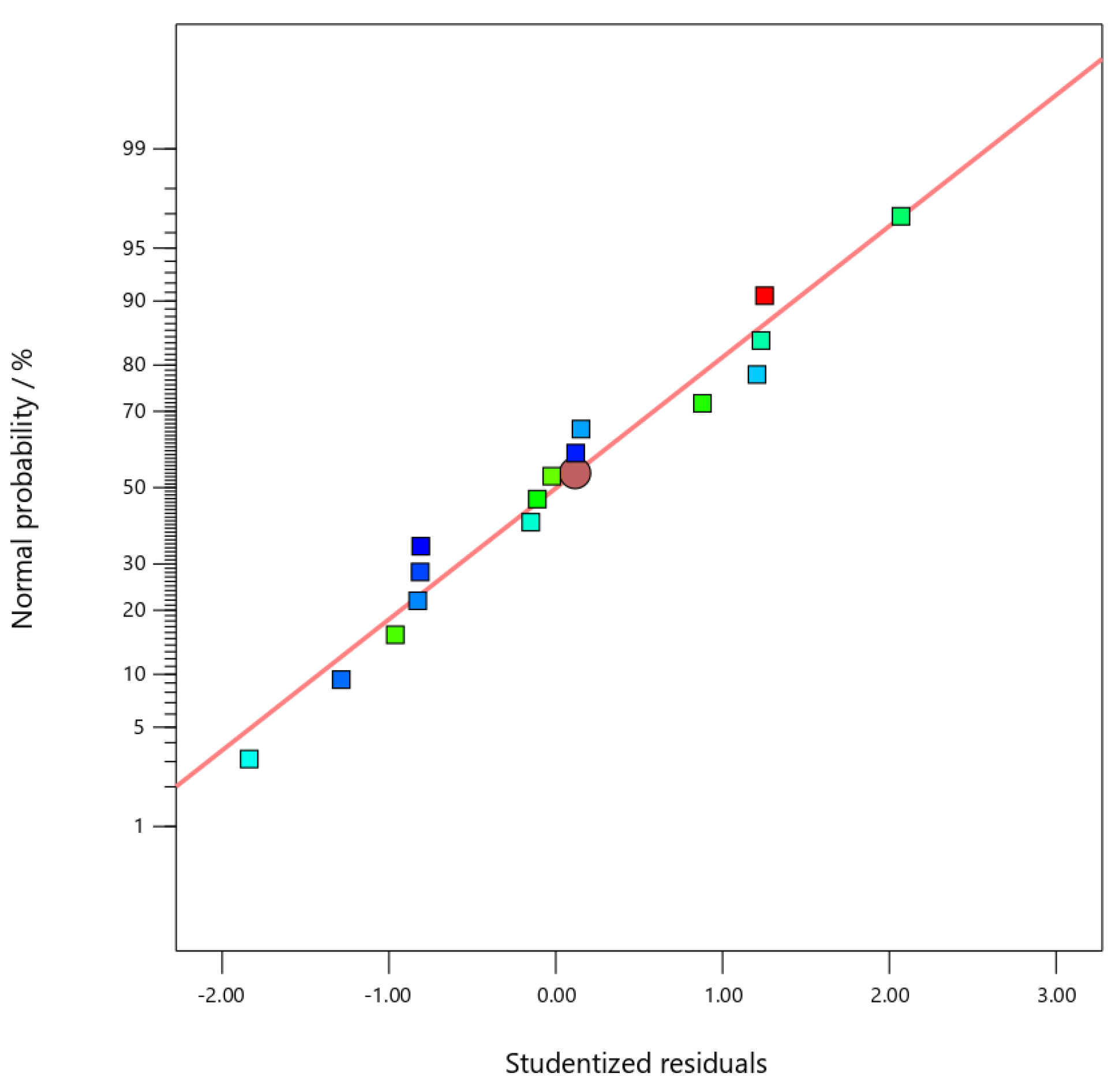

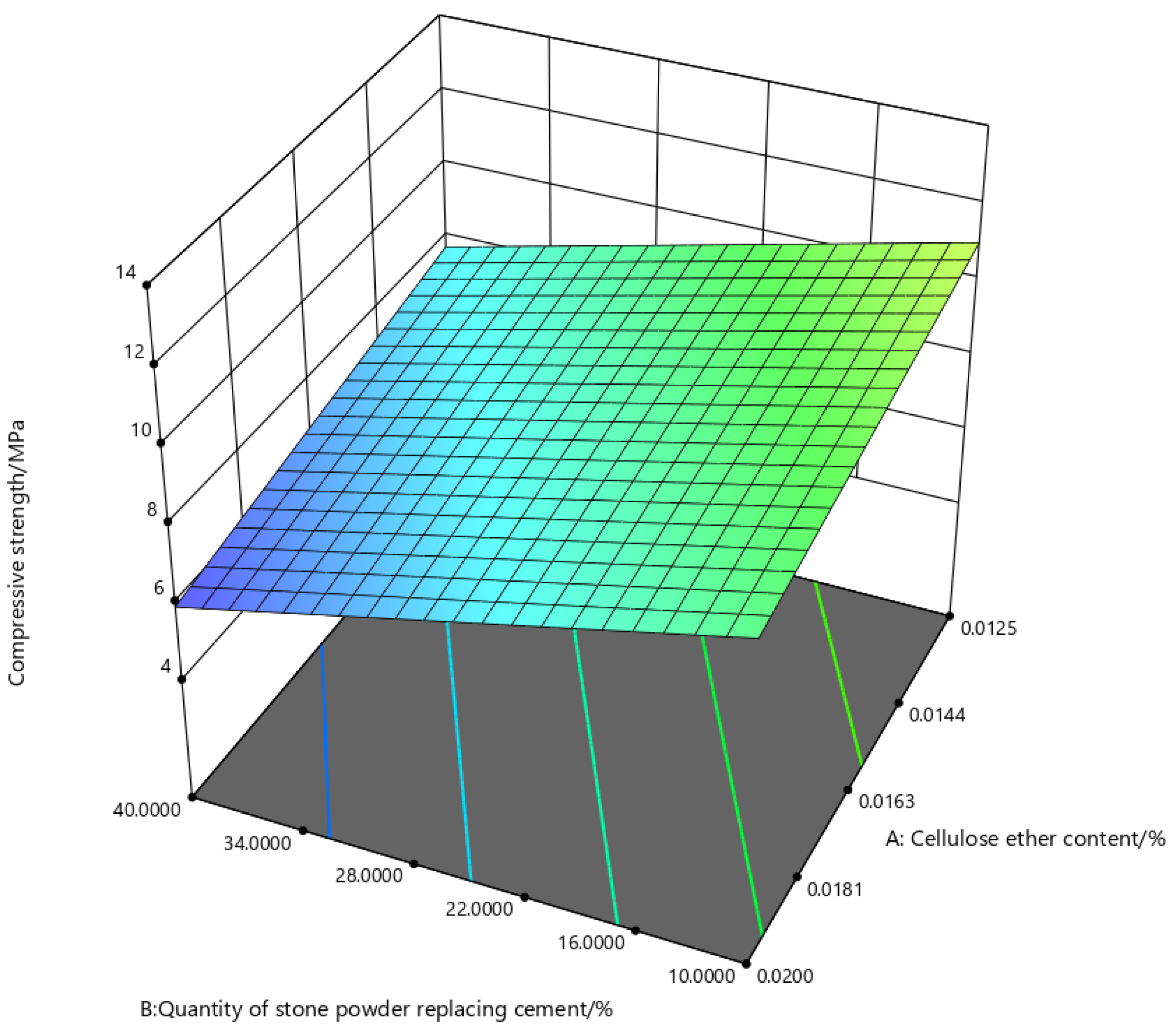

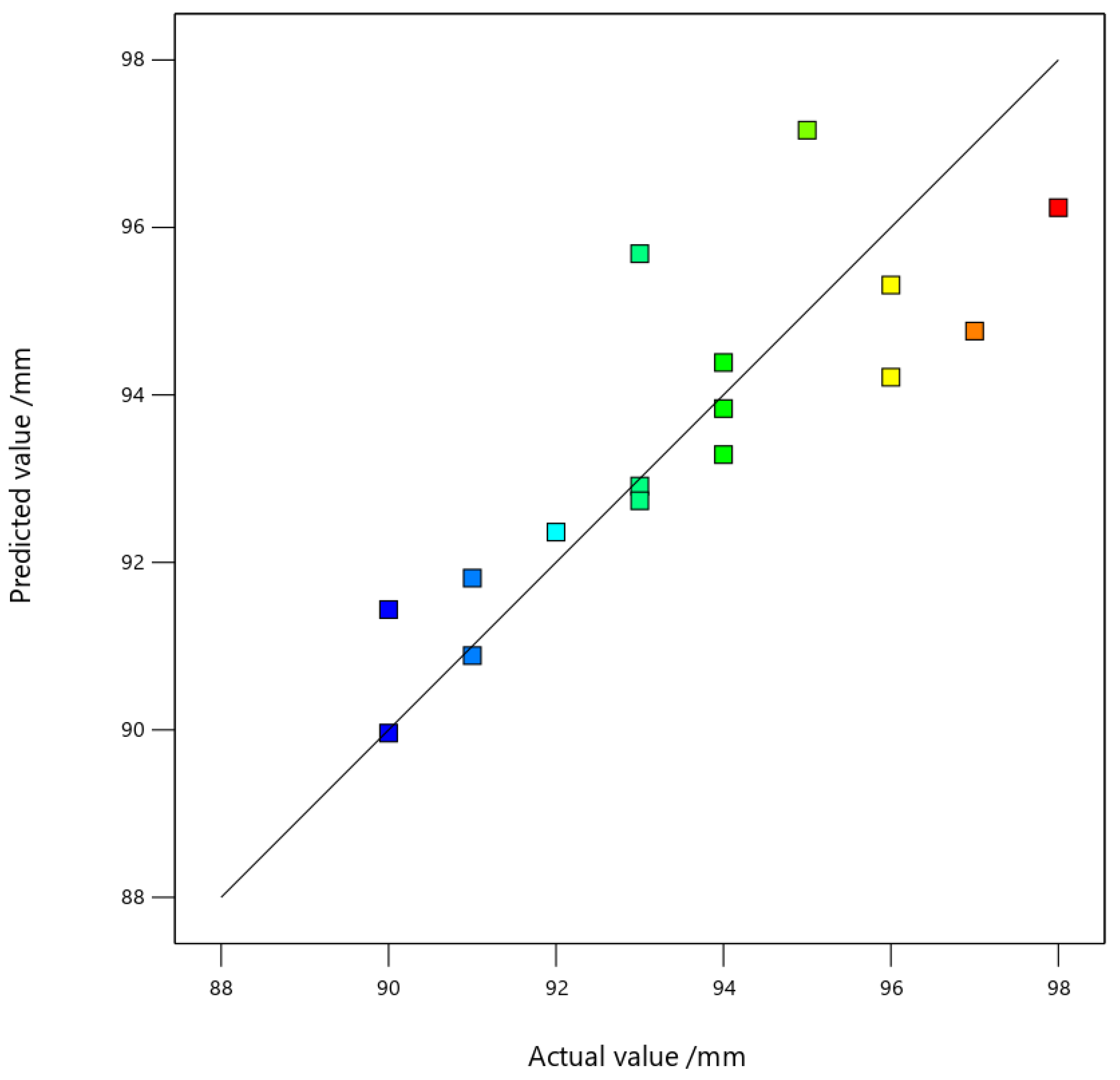

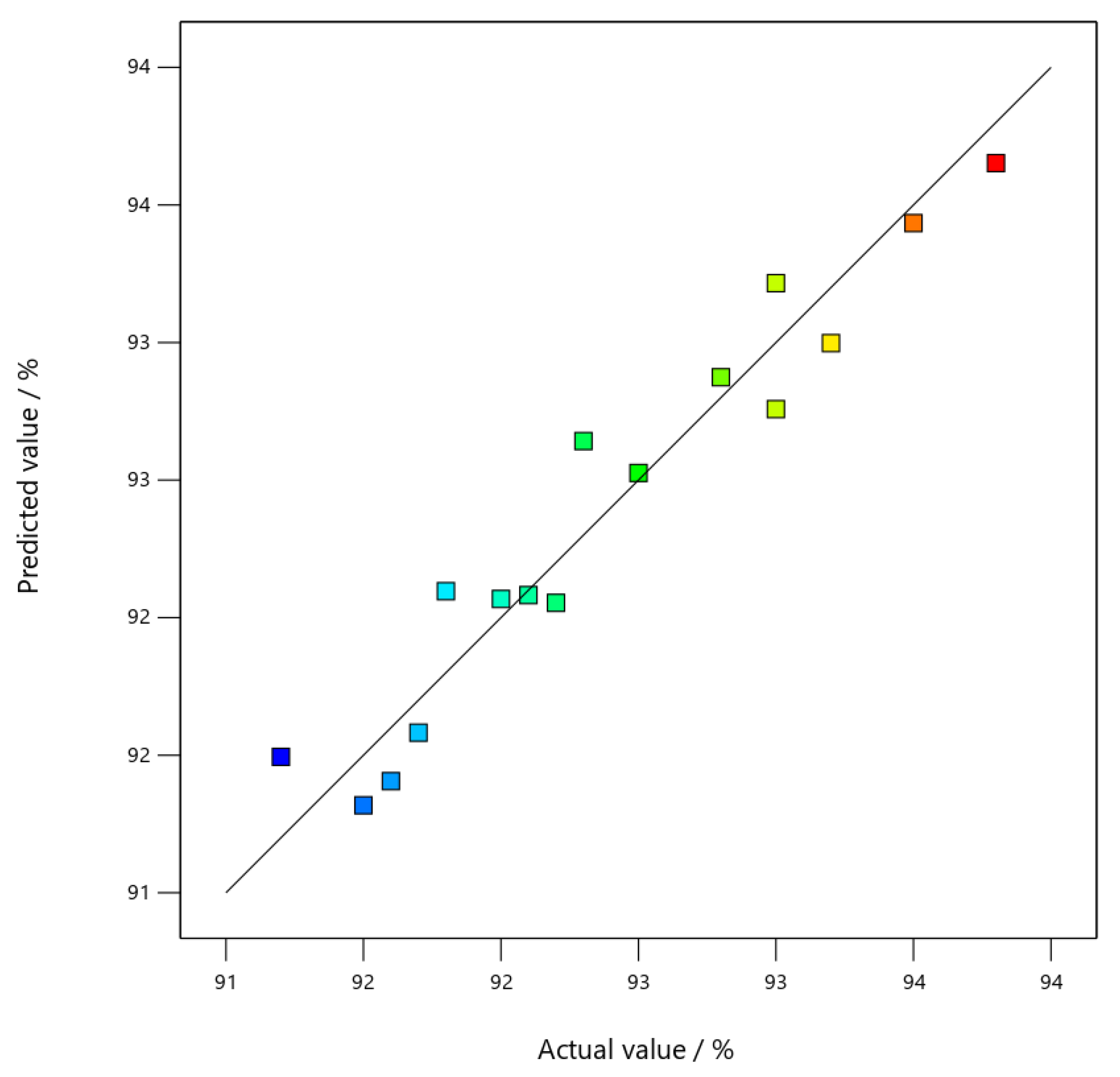

3) orthogonal experimental design with response surface methodology (RSM) and employs repeated tests and residual analysis to validate the predictive models. This approach enables a systematic quantification of the main and interactive effects of CE dosage and other key variables (stone powder-to-cement replacement ratio, manufactured-sand-to-river-sand replacement ratio, PVA dosage and bentonite dosage) on the properties of premixed mortars, thereby providing a scientific basis for formula optimization.

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Raw Materials

Ordinary Portland cement (P·O 42.5), conforming to the Chinese standard GB 175-2007, was used as the primary cementitious material. Its technical properties are summarized in

Table 1. Natural river sand and manufactured sand served as fine aggregates. The river sand, with a fineness modulus of 2.4, was classified as medium sand in Zone II. The manufactured sand, produced by crushing limestone and tuff, had a fineness modulus of 2.7. Key properties of both sands, tested according to GB/T 14684-2022, are presented in

Table 2.

Stone powder, a by-product collected during the production of manufactured sand, was utilized after drying and sieving. Its primary characteristics, evaluated against the specifications of GB/T 35164-2017 and JGJ/T 318-2014, are listed in

Table 3. Fineness refers to the particle size distribution of stone powder, typically expressed as a percentage of material passing through a sieve of a specific aperture. The determination of fineness is conducted through sieve analysis utilizing a standard sieve. The methylene blue value serves as an overall indicator to ascertain the presence of expansive clay minerals (such as clay powder) within the stone powder and to quantify their content. This is achieved by progressively adding methylene blue solution to a suspension created by mixing aggregates with water, observing for the emergence of a light blue halo indicating free methylene blue, which reflects the adsorption characteristics of the aggregate towards the dye solution. The activity index indicates the content of reactive components within the stone powder that can participate in the hydration reaction of cement, thereby influencing the performance of the pre-mixed mortar. The activity index is determined through chemical analysis. Hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose ether (HPMC), complying with the JC/T 2190-2013 standard and with a viscosity of 40,000 MPa·s, was employed as the cellulose ether. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers had a tensile strength ≥ 1200 MPa, a length of 6 mm, and a diameter of 18–25 μm. Sodium bentonite, with a montmorillonite content ≥ 85% and a swelling capacity ≥ 15 mL/g, was also used.

2.2. Apparatus

The main instruments and equipment utilized in the experiments include the JJ-5 planetary cement mortar mixer (compliant with JC/T 681-2022 standards), the NYL-300 compression testing machine, the KZJ-500 electric flexural testing machine, and a standard curing chamber (maintaining a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of over 95%), provided by Zhejiang Huannan Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., established on 25 March 2005, is located in Qianshang Village, Daoxu Subdistrict, Shangyu District, Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. Additionally, the mortar consistency meter SC-145, the mortar setting time tester ZKS-100, and the drying shrinkage measurement device JG/170 were supplied by Shaoxing Jiaoche Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., established on 7 June 2016, is located in No. 10, Tunbei Wujiazhuang, Xintunnan Village, Daoxu Subdistrict, Shangyu District, Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. The water retention measurement device 100 × 25 was provided by Shaoxing QianNeng Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., established on 29 September 2012, is located in No. 69, Zhongxing Road, Daoxu Subdistrict, Shangyu District, Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. Furthermore, the microcomputer-controlled electronic universal testing machine (used for tensile bond strength testing) DN-W50KN was sourced from Shandong Jinan KJ Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., established on 30 September 2019, is located in Room 301, Unit 3, Building 6, Meili Xincju Second District, Huaiyin District, Jinan, Shandong Province, China. and the rapid freeze–thaw testing machine TDR-9 was provided by Shanghai Luda Experimental Instrument Co., Ltd., established on 25 April 2000, is located in No. 32, Xinxin Road, Shedun Town, Songjiang District, Shanghai, China.

2.3. Experimental Design

Based on the ‘Specification for the Design of Mortar Mix Proportions’ (JGJ/T 98-2010) and referring to the theoretical mix proportions outlined in the ‘Specification for the Design of Premixed Mortar Proportions’ (DBJ33/T1314-2024), preliminary tests were conducted to validate the applicability of different materials and additives at varying levels in the premixed mortar. An orthogonal array testing design was adopted, specifically an L16 (4

5) layout involving five factors at four levels each [

21,

22]. The five factors considered were: cellulose ether content (CE), stone powder replacement ratio for cement (SP), manufactured sand replacement ratio for river sand (MS), PVA content (PVA), and bentonite content (BT). The levels for each factor, defined as the percentage by mass of the respective material, are detailed in

Table 4. The contents of PVA, bentonite, stone powder, and CE are expressed as a percentage of the total cementitious material mass. The manufactured sand content is given as a percentage of the total fine aggregate mass. The total mass of stone powder and cement was fixed at 150 g, the total mass of river sand and manufactured sand was fixed at 850 g, and the water content was fixed at 165 g. The experimental matrix was constructed based on the principles of orthogonal design [

26].

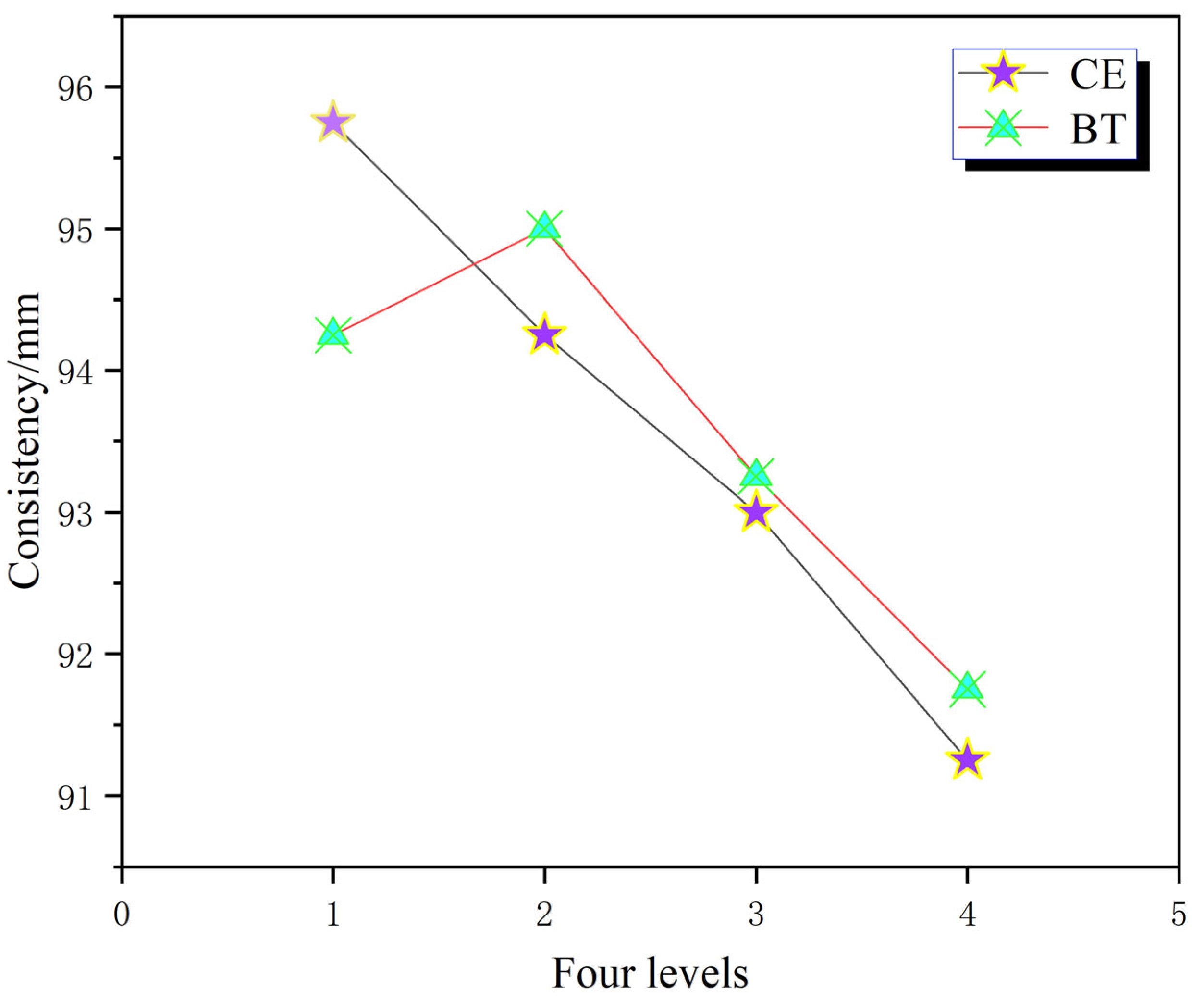

Following the technical standards for application of premixed mortar, the key fresh properties assessed for masonry and plastering mortars were consistency (Note: Measured as the penetration depth of a standard cone; a greater depth indicates higher fluidity/consistency) and water retention. The primary hardened property evaluated was the 28-day compressive strength. Accordingly, the orthogonal experiments were designed to measure these three performance indicators: consistency, water retention, and compressive strength [

27].