Microstructure and Properties of Inconel 718/WC Composite Coating on Mold Copper Plate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phase Analysis

3.2. Microstructure and Element Distribution

3.3. Microhardness

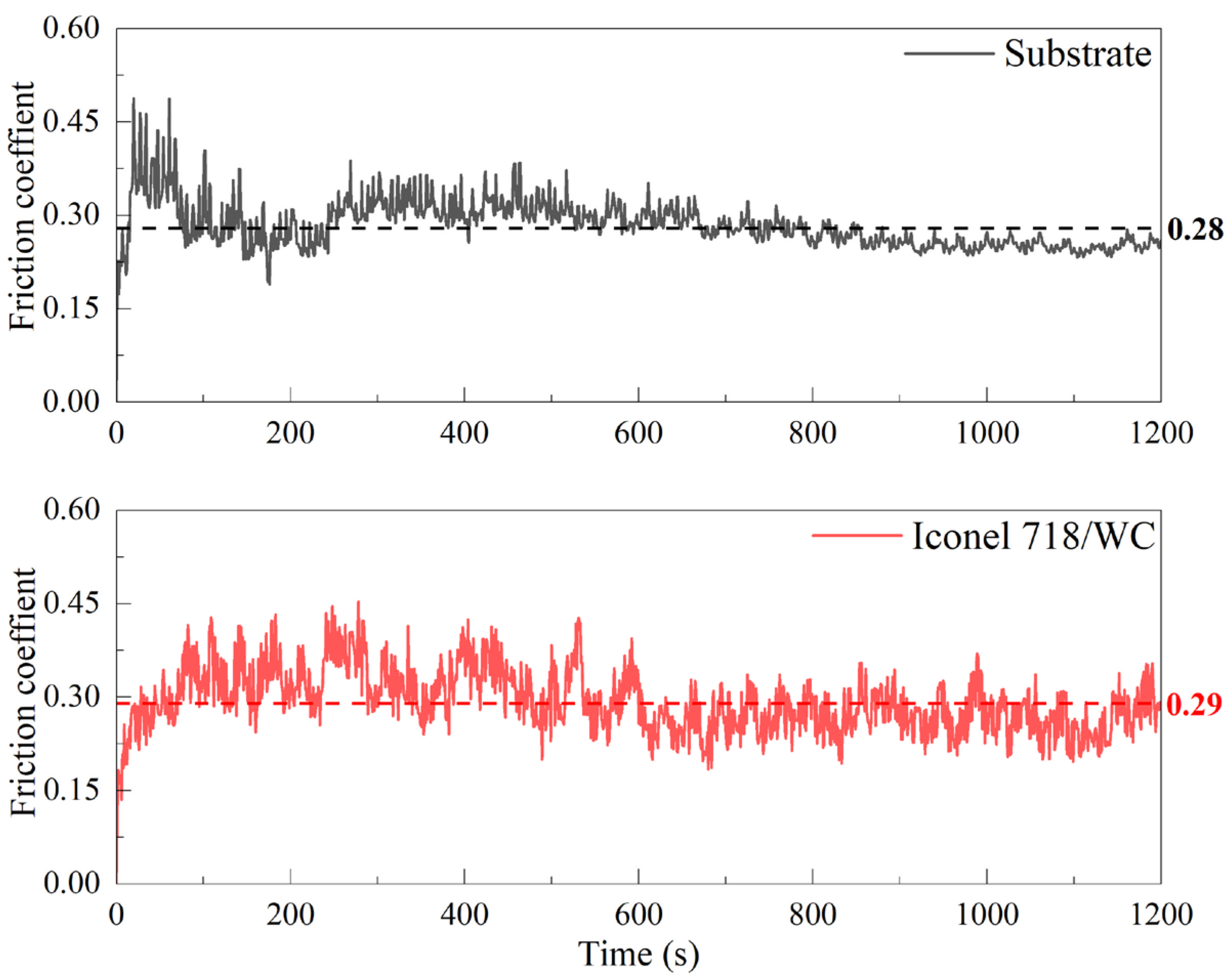

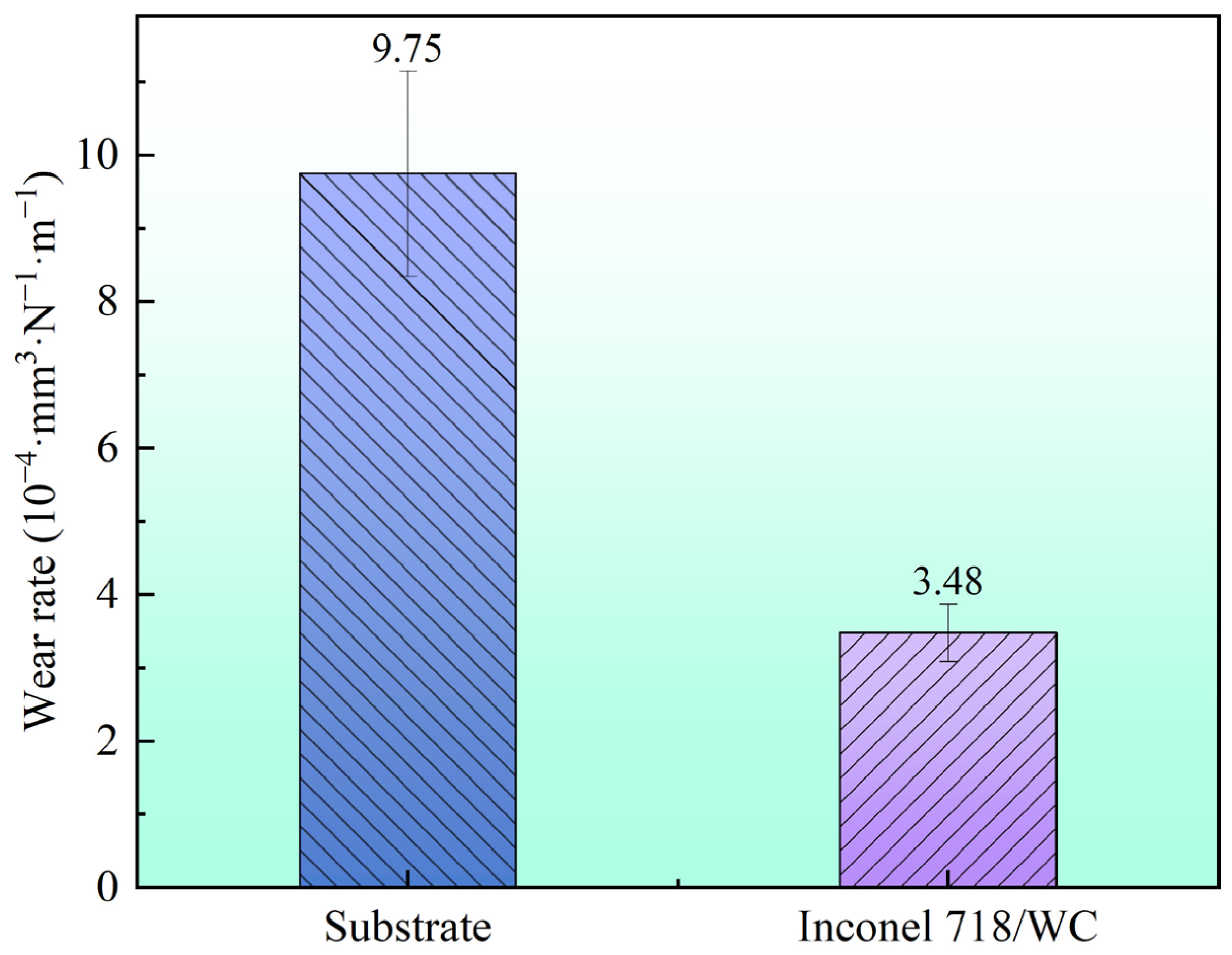

3.4. Friction and Wear

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study successfully fabricated defect-free Inconel 718/WC composite coatings metallurgically bonded to a Cr-Zr-Cu alloy substrate using a CO2 laser. The coatings primarily consist of γ-Ni solid solution and carbides such as M3W3C, MC, and W2C. These carbides formed through the decomposition and subsequent reaction of WC particles within the molten pool.

- (2)

- The coating cross-section is dense and smooth, free of cracks and pores. Columnar compounds, some growing parallel to the surface, are distributed in the intermediate region. Elemental mapping confirmed limited interdiffusion of Ni, Cr, and W with the substrate, indicating a sound interfacial bond. Short-range ordered triangular precipitates and elongated/spherical light-gray phases (W, Cr, and Mo-rich carbides) are observed within the coating. These hard phases are dispersed in the γ-Ni matrix, effectively pinning dislocations and inhibiting plastic deformation, thereby enhancing mechanical properties. Fine compounds formed at the coating bottom due to the high thermal gradient, strengthening the bonding interface.

- (3)

- The composite coating had an average microhardness of about 851.7 HV0.5 and a maximum value of 934.5 HV0.5. Its average microhardness was 11.5 times that of the substrate (74 HV0.5). The significant enhancement in hardness is attributed to grain refinement strengthening and dispersion strengthening induced by various hard carbide precipitates.

- (4)

- During high temperature friction and wear at 400 °C, the coating and substrate demonstrated similar average friction coefficients (approximately 0.29). However, the wear rate of the coating was measured at 3.48 × 10−4·mm3·N−1·m−1, merely 35.7% of the substrate’s wear rate, indicating substantial improvement in wear resistance. Analysis of the worn surfaces revealed that the coating’s wear mechanism was primarily abrasive wear, accompanied by oxidative wear. The uniformly distributed hard carbides played a dominant role in resisting wear, while the γ-Ni matrix provided essential structural support. This synergistic interaction between the hard phases and ductile matrix resulted in exceptional high-temperature wear resistance and creep performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Louhenkilpi, S. Treatise on Process Metallurgy, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 343–383. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, R.I.; Isac, M.M. Continuous Casting Practices for Steel: Past, Present and Future. Metals 2022, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vynnycky, M. Continuous casting. Metals 2019, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J.; Yuan, L. Study on Wear Properties of High Hardness and High Thermal Conductivity Copper Alloy for Crystallization Roller. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 3225–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Li, K.; Hao, L.; Tang, J.; Jin, X.; Yang, J. Simulation and experimental study of shot peening strengthening technology for turbine disk fir-tree slots. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1014, 178744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pang, C.; Xue, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Q. Chemiresistive SnO2-based hydrogen sensor fabricated by chemical bath deposition and chemical vapor deposition. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 433, 137543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, T.S.; Agrawal, R.D.; Prakash, S. Hot corrosion of some superalloys and role of high-velocity oxy-fuel spray coatings—A review. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 198, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miao, J.; Shi, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Y. Sustainable stabilization/solidification of electroplating sludge using a low-carbon ternary cementitious binder. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lv, Z.; Cao, J.; Tong, Y.; Sun, M.; Cui, C.; Wang, X. Effect of SiC and TiC content on microstructure and wear behavior of Ni-based composite coating manufactured by laser cladding on Ti–6Al–4V. Wear 2024, 552, 205431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Niu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, G.; Ke, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, C. Microstructure and wear behavior of in-situ synthesized TiC-reinforced CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy prepared by laser cladding. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 670, 160720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Xu, Z.; Gao, Q.; Alfano, M.; Yuan, J. Effect of processing parameters on the microhardness, shear, and tensile properties of layer-cladded Inconel 718. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 4725–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, A. Comprehensive analysis of morphology, microstructure, and mechanical characterization of parameters in the Inconel 718 laser cladding process on AISI 1050. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2024, 238, 10772–10784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, T.; Song, Q.; Xue, B.; Cui, H. Microstructure and performance optimization of laser cladding nano-TiC modified nickel-based alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.R.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, H.S. Enhancement of mechanical and tribological performance of Ti–6Al–4V alloy by laser surface alloying with Inconel 625 and SiC precursor materials. Friction 2024, 12, 2089–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Chen, L.; Lv, J.; Yu, T.; Zhao, J. No-impact trajectory design and fabrication of surface structured CBN grinding wheel by laser cladding remelting method. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtuluş, V.; Görgülü, B.; Eraslan, F.S.; Gecu, R. Improving wear and corrosion resistance of Ti-alloyed nodular cast irons by Al2O3 and SiC-reinforced Al2O3 coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 498, 131809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, R.; Feng, A.; Feng, H. Effect of rare earth La2O3 particles on structure and properties of laser cladding WC-Ni60 composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, Q.; Guan, X.; Tian, F.; Li, B.; Zhan, X. Effect of WC on the microstructure and wear resistance of Invar-WC coatings prepared by laser fusion cladding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 34, 2285–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Cui, T.; Wang, W.; Lin, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Qi, H. Laser cladding WC/Fe composite coating on nose rail of turnout: Microstructure characteristics and wear behaviors. Wear 2025, 570, 205929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Xu, D.; Min, J.; Guo, Y.; Dai, G.; Sun, Z.; Chang, H.; Jia, Z. Influence of WC particle size on microstructural evolution and wear behavior of laser cladding WC/Ti6Al4V composite coatings. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 47119–47131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Shu, L.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Li, A.; Huang, T.; Dong, H. Study on the preparation and wear properties of laser cladded Incoel718/WC gradient composite coatings. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 111080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, W.; Xu, Y.; Wei, S.; Luo, J. Corrosion and wear resistance of inconel 625 and inconel 718 laser claddings on 45 steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1013, 178368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Watanabe, K.I.; Marquez, L.; Arrieta, E.; Murr, L.E.; Wicker, R.B.; Medina, F. Microstructure and hardness properties for laser powder directed energy deposition cladding of Inconel 718 on electron beam powder-bed fusion fabricated Inconel 625 substrates: As-built and post-process heat treated. Results Mater. 2025, 25, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yao, Z.; Wang, F.; Chi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tofil, S.; Yao, J. Grain refinement and Laves phase dispersion by high-intensity ultrasonic vibration in laser cladding of Inconel 718. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 308, 563–8575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilanlou, M.; Razavi, R.S.; Nourollahi, A.; Hosseini, S.; Haghighat, S. Prediction of the geometric characteristics of the laser cladding of Inconel 718 on the Inconel 738 substrate via genetic algorithm and linear regression. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 156, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, H.; Li, G.; Xu, R.; Ma, N.; Liang, H.; Lin, J.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, Z. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Clad Inconel 718 Coatings on Continuous Casting Mold Copper Plate. Lubricants 2025, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhu, L.; Xue, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ning, J.; Qin, S. Microstructure and properties of IN718/WC-12Co composite coating by laser cladding. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 9218–9228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cu | Cr | Zr |

|---|---|---|

| 99.07 | 0.68 | 0.25 |

| Element | C | Cr | Nb | Mo | Ti | Al | Co | Mn | Si | Ni | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | 0.08 | 19 | 4.8 | 3 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 1.2 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 55 | 15.17 |

| Laser Power (W) | Scanning Speed (mm/min) | Spot Diameter (mm) | Overlap Rate (%) | Preheating Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 120 | 3 | 30 | 200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Jin, H.; Li, G.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z. Microstructure and Properties of Inconel 718/WC Composite Coating on Mold Copper Plate. Coatings 2025, 15, 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121394

Liu Y, Jin H, Li G, Li P, Zhang S, Zhang Z. Microstructure and Properties of Inconel 718/WC Composite Coating on Mold Copper Plate. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121394

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yu, Haiquan Jin, Guohui Li, Peixuan Li, Shuai Zhang, and Zhanhui Zhang. 2025. "Microstructure and Properties of Inconel 718/WC Composite Coating on Mold Copper Plate" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121394

APA StyleLiu, Y., Jin, H., Li, G., Li, P., Zhang, S., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Microstructure and Properties of Inconel 718/WC Composite Coating on Mold Copper Plate. Coatings, 15(12), 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121394