1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was mitigated by widespread social immunization achieved via vaccination and natural infection. However, individuals with risk factors for severe disease progression, such as those with immunocompromised conditions, morbid obesity, or severe renal dysfunction, remain at risk of requiring intensive care. These high-risk populations are particularly vulnerable, necessitating prompt antiviral treatment upon COVID-19 diagnosis [

1]. However, the efficacy of antiviral drugs in preventing disease progression has been reported to diminish in individuals who maintain immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) through additional booster vaccinations. For example, the treatment of symptomatic COVID-19 with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir showed a relative risk reduction (89%) in hospitalization or death by day 28 among nonhospitalized high-risk patients [

2]. In contrast, it was recently reported that nirmatrelvir/ritonavir does not significantly impact the time to sustained symptom alleviation or reduce the risk of hospitalization or death in patients at standard risk or in those fully vaccinated who had at least one risk factor for severe disease [

3]. Similarly, while molnupiravir initially showed a relative risk reduction (30%) in hospitalization or death among at-risk, unvaccinated adults in 2020 [

4], the subsequent evidence did not reveal a significant benefit in reducing COVID-19-associated hospitalizations or deaths among high-risk vaccinated individuals in the community [

5].

In Japan, the proportion of individuals receiving COVID-19 vaccine boosters has declined as daily life returned to normal, while some countries have decided to maintain specific vaccination levels for high-risk populations [

6,

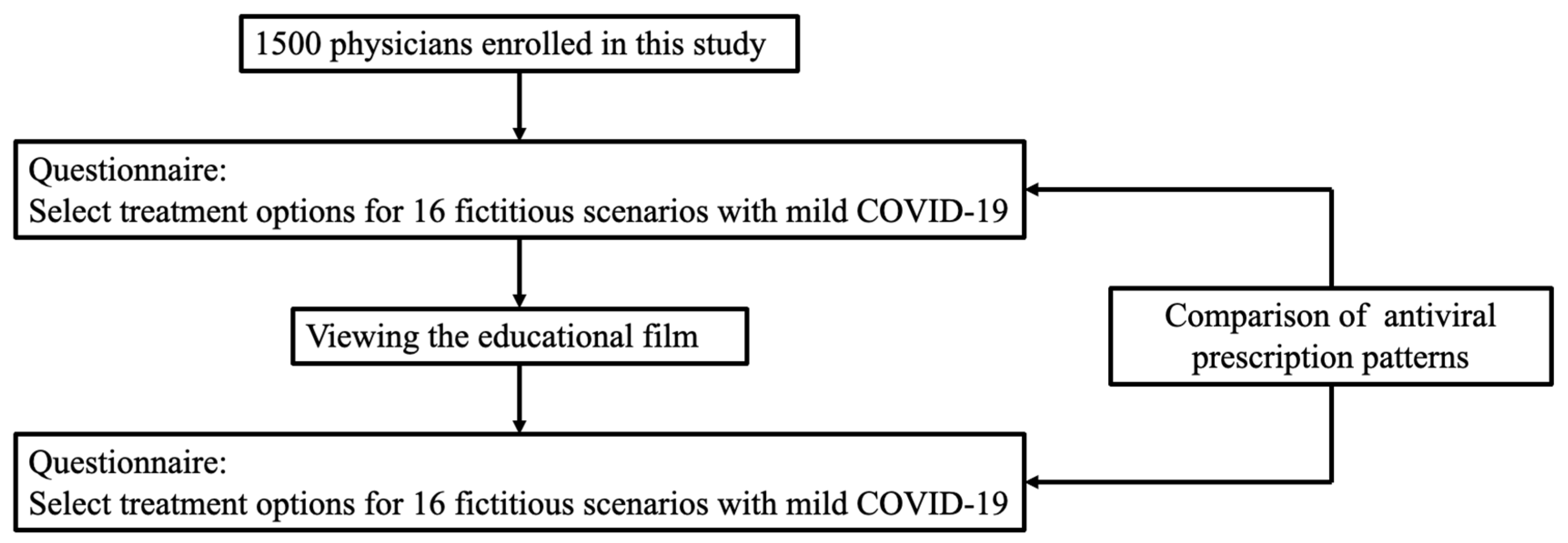

7]. Given the limited duration of vaccine-induced immunity, the number of individuals at risk for severe COVID-19 progression who have not received additional booster doses is likely increasing. Thus, to prevent a resurgence of severe COVID-19 cases, physicians must recognize the risk factors for severe disease progression in the context of patient’s current vaccination status. However, there is a lack of surveys assessing physicians’ knowledge of the risk factors for severe COVID-19, particularly when taking into account vaccination status. Additionally, there is a paucity of interventional studies evaluating the impact of educational tools on antiviral agent prescription behaviors. To address these gaps, we performed a nationwide survey assessing the antiviral prescription patterns among physicians managing COVID-19 patients before and after watching an educational film with 16 fictitious scenarios of patients with mild COVID-19 who had various risk factors for severe disease and different vaccination statuses.

3. Discussion

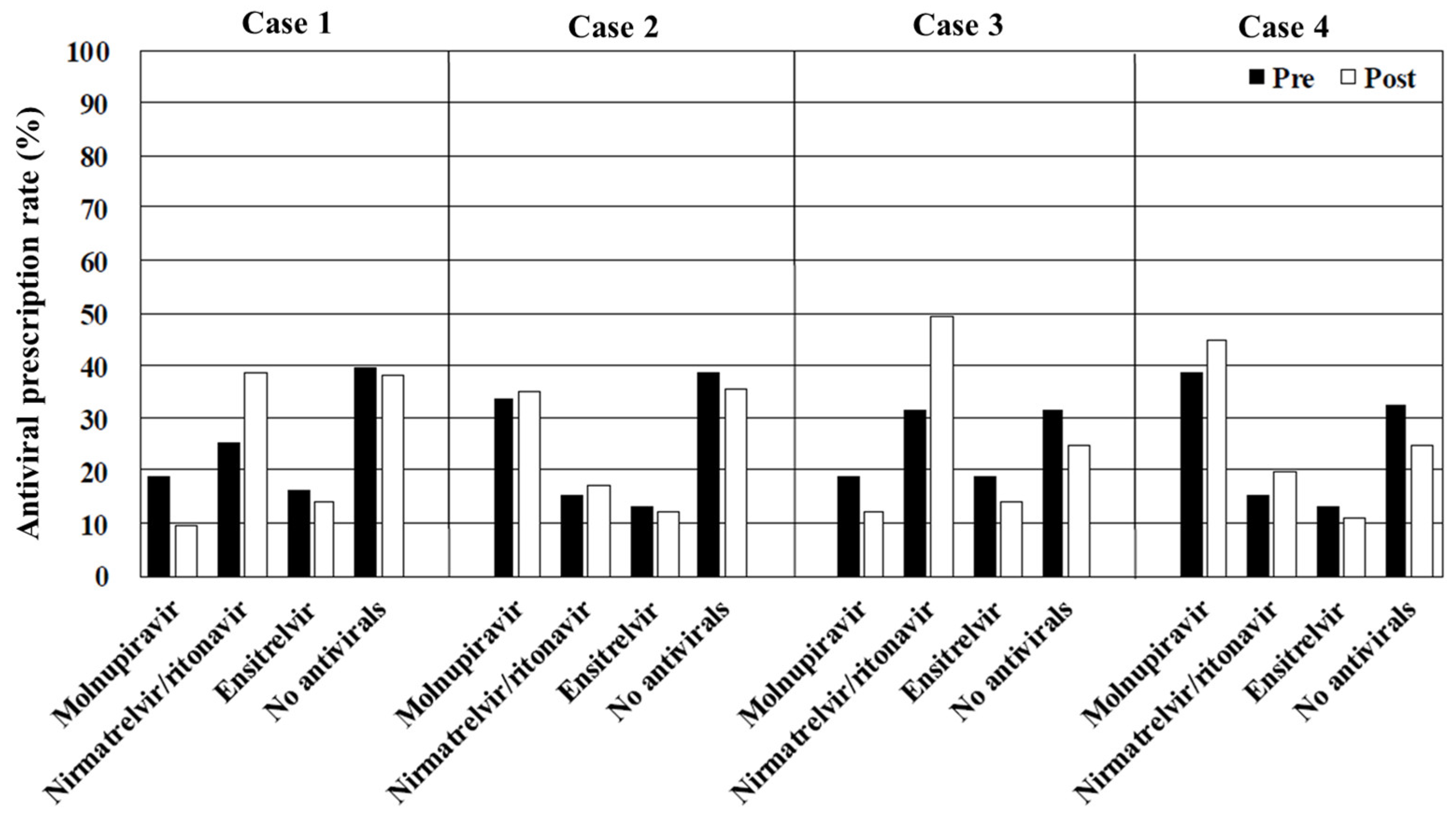

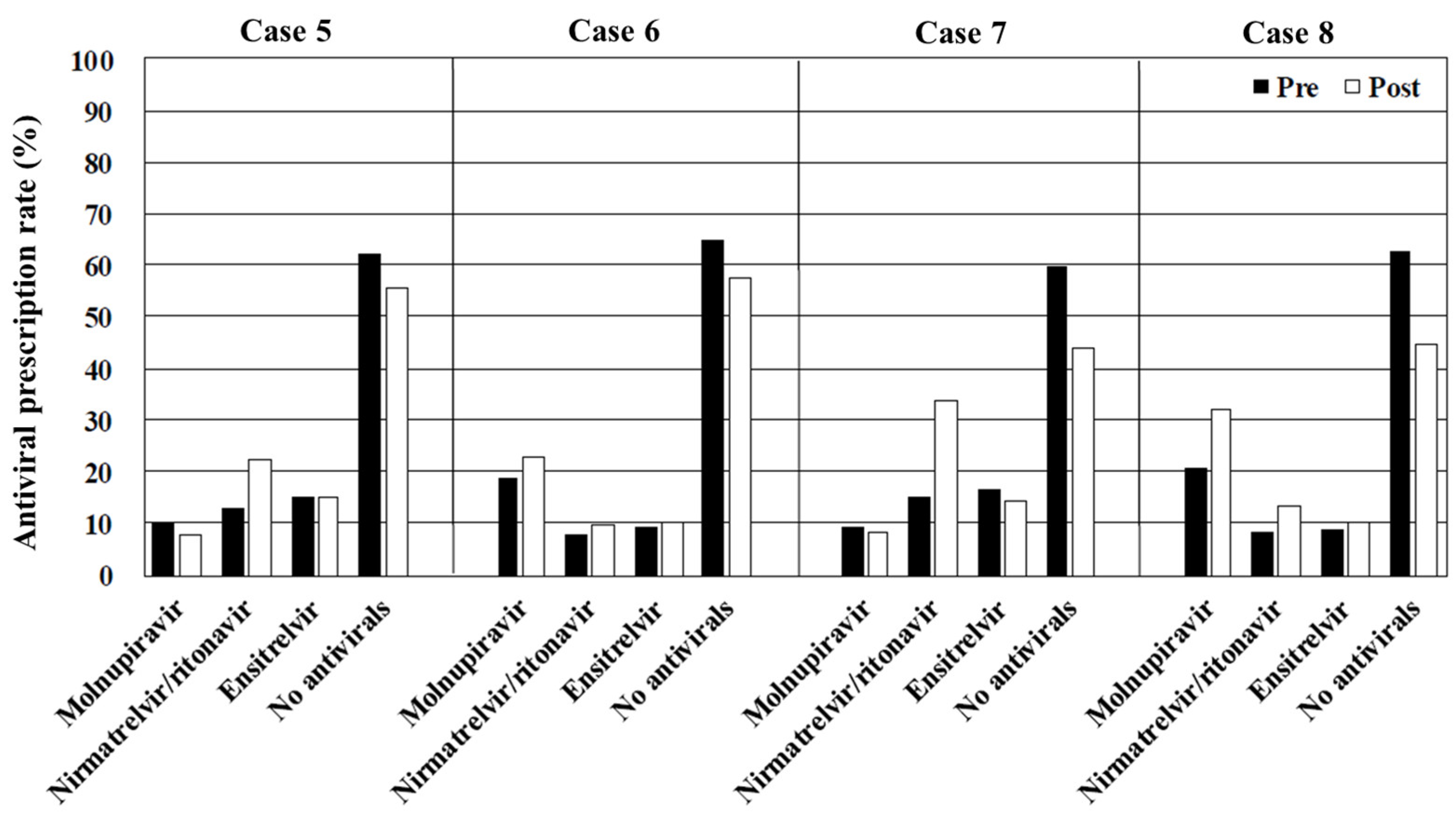

We demonstrated that viewing an educational film of 16 fictitious scenarios of adult patients with COVID-19 with varying risk factors for severe disease and different vaccination statuses significantly increased the rate of antiviral prescription, particularly nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, among the patients who were immunosuppressed or had obesity. Despite this improvement, approximately 20–40% of the participating physicians indicated that they would not prescribe antivirals, even for immunosuppressed patients where such treatment was necessary to prevent severe disease progression. Molnupiravir emerged as the most frequently chosen antiviral agent for the patients taking CYP3A-metabolized medications. Furthermore, the educational film effectively reduced the proportion of physicians who relied solely on their personal experience with antiviral medications when making prescription decisions, promoting a more evidence-based approach.

In cases 1–4 (immunosuppressed), the prescription rate for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir was highest among the patients not taking CYP3A-metabolized medications, while molnupiravir was most frequently prescribed for those who were. Notably, approximately 30% of the physicians stated that they would not prescribe antivirals in these scenarios. Underlying conditions, such as immunosuppression caused by corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive medications and solid organ or blood stem cell transplantation, are well-established risk factors for severe disease progression [

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, immunocompromised patients show more prolonged COVID-19 shedding compared with that of immunocompetent individuals [

11]. Given the inadequate antibody responses to vaccination in this population, antiviral therapy is strongly recommended, regardless of their COVID-19 vaccination status [

12,

13]. Although the educational film emphasized the importance of antiviral treatment for immunosuppressed patients, the increase in the prescription rate before and after viewing the film remained insufficient. This may be because the educational content was primarily based on the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) instead of real-world clinical case presentations of COVID-19. The most frequently cited reason for not prescribing antivirals was the perception of mild symptoms, suggesting that physicians underestimate the heightened risk of disease progression in immunosuppressed patients. Thus, it is crucial to recognize that the decision to administer oral antivirals to patients with mild COVID-19 must be based on the risk of disease progression. This critical point was inadequately emphasized in the educational film, potentially contributing to the suboptimal impact on antiviral prescription practices.

The prescription patterns in cases 5–8 (obesity) were similar to those in the scenarios involving patients with immunosuppression (cases 1–4), with an overall antiviral prescription rate of approximately 50%. Other underlying conditions, including obesity, dialysis, diabetes, and cancer, are also recognized as significant risk factors for severe disease progression [

10,

14,

15]. Furthermore, patients with severe COVID-19 tend to have a higher body mass index compared with those with nonsevere disease, underscoring the necessity for antiviral therapy in cases of obesity [

16,

17]. Obesity is associated with poor outcomes in patients with COVID-19 due to multiple mechanisms, such as chronic inflammation driven by increased cytokine production, impaired respiratory function, pulmonary perfusion issues (e.g., vascular thrombosis), and other vascular complications [

18,

19]. Although immunosuppression diminishes vaccine effectiveness [

12], there is no evidence suggesting that obesity directly weakens vaccine efficacy. Nevertheless, vaccine effectiveness declines over time. Individuals aged 18–64 years who received at least three doses showed decreased vaccine effectiveness (46.4% at 3–5 months vs. 18.3% at 12–14 months post-vaccination), as did those aged ≥65 years, (65.3% at 3–5 months vs. 52.3% at 12–14 months) [

20]. Notably, meta-analysis revealed that hybrid immunity (i.e., prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination) provided 97.4% effectiveness against hospitalization and disease progression at 12 months [

21]. Antivirals are strongly recommended for patients with obesity who do not have a recent vaccination history. However, the educational film’s impact on prescribing practices in this population was suboptimal, increasing from 40.5% to 56.1% in case 7 (obesity, unvaccinated, and no CYP3A-metabolized drugs) and from 37.0% to 55.5% in case 8 (obesity, unvaccinated, and CYP3A-metabolized drugs). Symptomatic treatment may be considered a viable option for patients with a recent vaccination history.

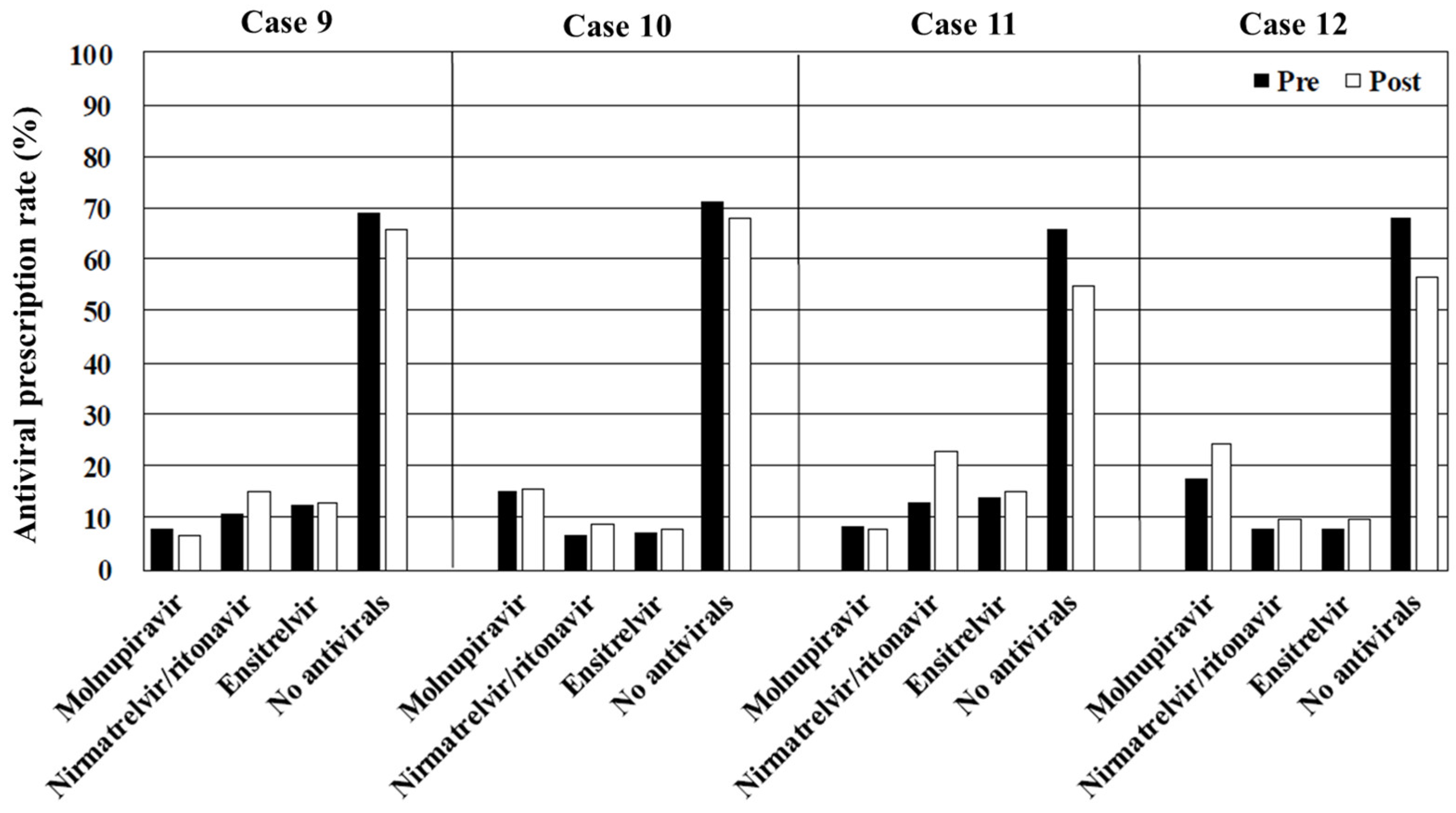

In cases 9–16 (hypertension or hyperlipidemia and no risk of severe disease progression), the antiviral prescription rates were relatively lower compared with those for the patients with an immunosuppressed status or obesity. Chronic conditions, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia alone, are not classified as high-risk factors for severe disease progression [

10]. Following the viewing of the educational film, there was a modest increase in the prescription rates for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, from 10.9% to 14.8% in case 9 (hypertension or hyperlipidemia, vaccinated, and no CYP3A-metabolized drugs) and 12.7% to 22.5% in case 11 (hypertension or hyperlipidemia, unvaccinated, and no CYP3A-metabolized drugs). However, symptomatic treatment or ensitrelvir (an antiviral that shortens symptom duration) may be more appropriate in such cases [

22]. In fact, ensitrelvir was the most frequently selected antiviral for the patients without a risk of disease progression and not taking CYP3A-metabolized medication, both before and after viewing the educational film. This preference may be attributed to clinical trials, where ensitrelvir has mainly been tested on patients without risk factors for severe disease progression [

22].

Overall, our study demonstrated increased antiviral prescription rates after viewing the educational film, particularly among the patients at higher risk for disease progression. Thus, the film appeared to exert a positive influence on appropriate antiviral use. However, the rate of antiviral prescriptions for immunosuppressed patients was lower than expected, highlighting an area for improvement. Notably, the proportion of physicians citing a physician’s prior experience as the reason for their prescription decisions decreased, suggesting a shift toward evidence-based practices. Thus, educational interventions using short films may play a valuable role in promoting such practices. To enhance the effectiveness of these interventions, future educational films should incorporate case presentations alongside scientific evidence from RCTs. This combination may enhance physicians’ engagement and improve their ability to apply evidence-based approaches in real-world clinical scenarios.

The strength of this study lies in its distinction as, to our knowledge, the first large-scale investigation of the effects of educational interventions on the appropriate use of antivirals for COVID-19. However, there were several limitations. First, the film presented fictitious scenarios with limited information, including the patients’ underlying conditions, vaccination status, concomitant medications, chief complaints, and chest X-ray findings, to minimize the burden on the participants. Thus, the findings may not be a true reflection of real-world clinical practice. Second, the cost of drugs may influence a physician’s decision to prescribe antivirals in clinical settings. In Japan, the approximate costs per treatment course of molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, and ensitrelvir are USD 150, 200, and 100, respectively, for patients with a standard income. Third, the educational film emphasized the prevention of severe disease progression rather than a symptomatic cure. Consequently, the results do not reflect the impact of antiviral agents on COVID-19 symptoms. Last, because this study assessed the physicians’ intentions to prescribe antivirals immediately after viewing the educational film, the long-term effects of the intervention are unclear.

In conclusion, the educational film effectively increased the overall antiviral prescription rates. However, subgroup analysis revealed that the prescribing rates remained suboptimal among the high-risk patients, particularly those who were immunosuppressed. This disparity underscores the need for targeted interventions to ensure appropriate antiviral use in vulnerable populations. Enhancing educational programs by incorporating the clinical experiences of severe COVID-19 cases and strengthening communication between high-level medical institutions and clinics may further improve prescription practices. This approach is particularly crucial for clinic physicians, who may rarely encounter severe COVID-19 cases, but play a key role in early intervention for high-risk patients.