Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents Against WHO Priority Bacterial Pathogens: A Strategic Review of In Vitro Clinical Efficacy, Innovations and Research Gaps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy

3. The Antimicrobial Effect of Essential Oils

3.1. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils

3.1.1. Disruption of Biofilm Formation

3.1.2. Modulation of Quorum Sensing Activity

3.1.3. Cellular Targets: Membrane Activity and Genetic Material

3.1.4. Dual Pro-Oxidant and Antioxidant Activities

3.1.5. Inhibition of Resistance Mechanisms

Efflux Pump Effect

β-Lactamase Inhibition

3.1.6. Additional Anti-Virulence Mechanisms

3.2. Antibacterial Efficacy of Selected Plant Essential Oils Against Resistant Clinical Pathogens

3.2.1. Cinnamon Essential Oils

3.2.2. Clove Essential Oils

3.2.3. Eucalyptus Essential Oils

3.2.4. Geranium Essential Oils

3.2.5. Lemongrass Essential Oils

3.2.6. Mentha Essential Oils

3.2.7. Oregano Essential Oils

3.2.8. Rosemary Essential Oils

3.2.9. Tea Tree Essential Oils

3.2.10. Thyme Essential Oils

3.2.11. Other Essential Oils

3.3. Methods Adopted for Testing the Antibacterial Activity of Plant Essential Oils

3.3.1. Microbiological Techniques for Evaluating EOs Antimicrobial Activity

3.3.2. Techniques for Studying Antimicrobial Mechanisms

Conventional Methods

Advanced Methods

3.3.3. Specialized Techniques and Emerging Techniques

Single-Cell Analysis Techniques

Computational Approaches

Microfluidics and Lab-on-a-Chip Devices

Omics Approaches

4. The Challenges for the Development of Essential Oils as Therapeutics

4.1. Variability of Essential Oils Yields and Bioactivity

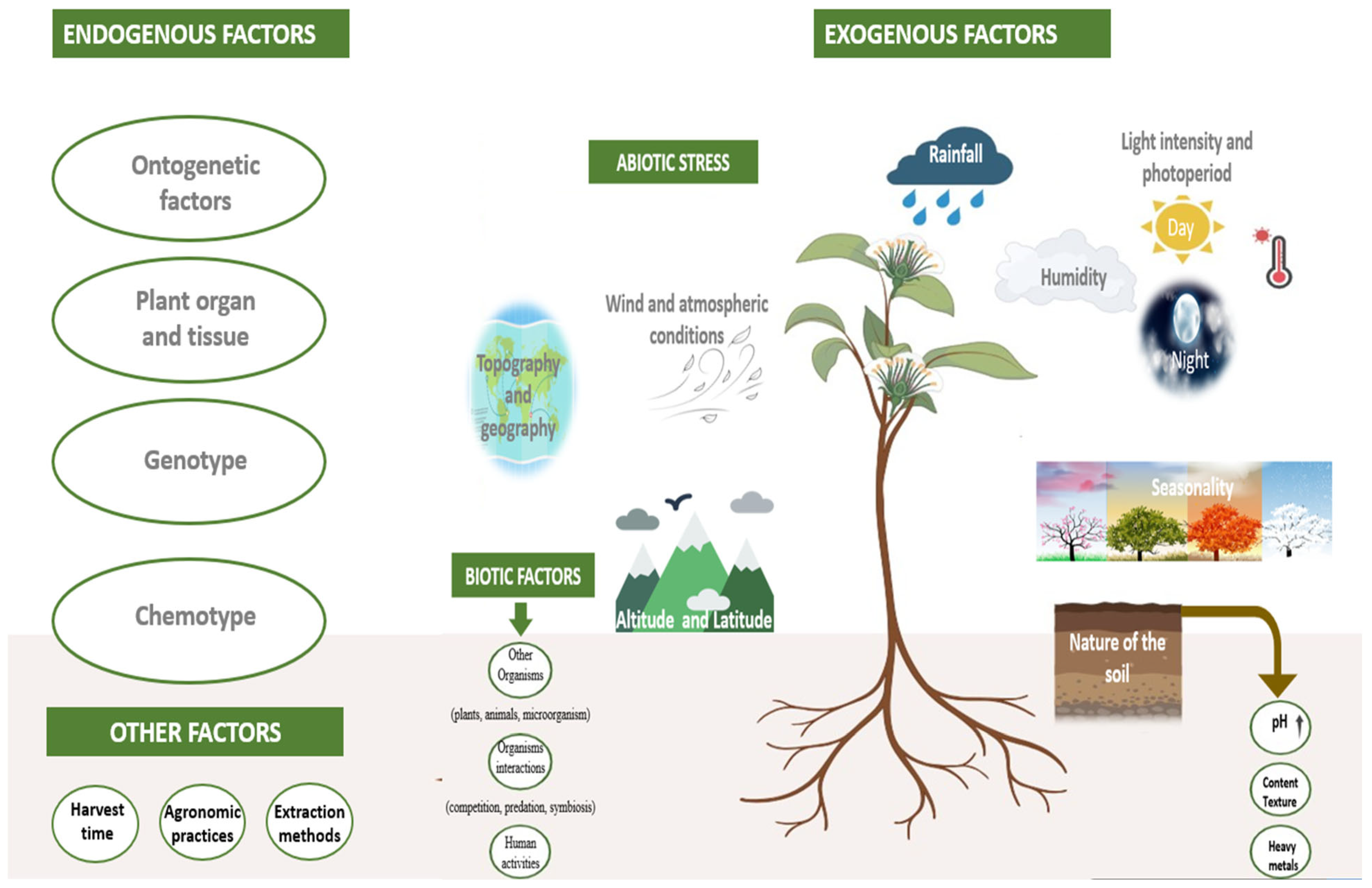

4.1.1. Endogenous and Exogenous Factors

4.1.2. Plant Age and Development

4.1.3. Plant Part Variability

4.1.4. Geographic and Environmental Influences

4.1.5. Seasonal Variations

4.1.6. Environmental Factors

4.1.7. Extraction Methods

4.2. Safety Concerns

4.3. Supply and Environmental Concerns

4.4. Regulatory Landscape

4.5. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties

4.6. Drug Interactions and Delivery

4.7. Co-Administration Challenges

4.8. Research Translation in Clinical Care

5. Understanding Essential Oils Resistance Development

6. Potential Advantages of Using Essential Oils in the Fight Against AMR

6.1. The Multi-Target Mechanisms of Plant EOs Against Antibiotic Resistant Clinical Isolates

6.2. Synergistic Effect of Plant EOs and Conventional Antibiotics

6.3. Nanoencapsulation of Plant Essential Oils

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| AIPs | Autoinducing peptides |

| AIs | Autoinducers |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| AST | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| BMD | Broth microdilution |

| BPPL | Bacterial Priority Pathogens List |

| CAC | Codex Alimentarius Commission |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CHT | Chitosan-based systems |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| CRKP | carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae |

| DESI | Desorption electrospray ionization |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EOCs | Plant EOs and their components |

| EOs | Plant essential oils |

| ESBLs | Extended-spectrum β-lactamases |

| EtBr-CW | Ethidium bromide cartwheel |

| EUCAST | and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FBECI | Fractional biofilm eradication concentration index |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FICI | Fractional inhibitory concentration index |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GACP | Good Agricultural and Collection Practices |

| GC | gas chromatography |

| GNB | Gram-negative bacteria |

| GPB | Gram-positive bacteria |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LOC | Lab-on-a-chip |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharides |

| MATE | Multidrug and toxic compound extrusion |

| MBC | minimum bactericidal concentrations |

| MBL | Metallo-beta-lactamase |

| MDR | multidrug-resistant |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MF | Major facilitator |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentrations |

| MOCS | Substance with more than one constituent |

| MRCoNS | Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| MRSA | Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MS | Mass spectrometer |

| NDS | Nanostructured delivery systems |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OmpF | Outer membrane protein F |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PEB | protein energy binding |

| QS | Quorum sensing |

| RND | Resistance nodulation division |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SMR | Staphylococcal multi-resistance |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| XDR | extensively drug-resistant |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Current Plant EO Extraction Methods

| Methods | Process | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Conventional methods | |||

| Cold-press extraction | -Used extensively for extraction of citrus peel EOs -Predominantly mechanical process which compresses peels or whole fruits to release the EOs -Released oils are washed from the resultant paste using water -Water may be evaporated to produce concentrated EOs | -Minimal heat exposure -Preserves natural oil properties -Suitable for citrus fruits |

|

| Hydrodistillation (HD) | -Plant material is placed into water and brought to boiling (100 °C) -Evaporated components are captured by condensation -Components are separated from residual water | -Extracts compounds with boiling points below 100 °C -Faster process than steam distillation -Convenient set-up and operation -Low cost -Efficient extraction due to better penetration | -Limited extraction of high boiling point compounds -Lower yield than steam distillation -Susceptibility to -hydrolysis reactions -High energy consumption -Prolonged process time -Potential volatile losses -Thermal degradation of sensitive compounds -High carbon dioxide emissions |

| Steam distillation (SD) | -Plant material is exposed to steam at 250–350 °C -EOs components evaporate and are captured in a condenser -Components separated from residual water | -Widely used at industrial scale -Lower susceptibility to hydrolysis than HD -Higher yields than HD -Convenient process control | -Thermal degradation and structural alterations, especially for monoterpenes, due to high temperature |

| Solvent extraction | -Plant material is mixed with a solvent (ethanol, methanol, acetone, ether, or hexane) -Mixture is heated to less than 100 °C -Extract is filtered to remove plant material -EOs- is concentrated by evaporation of solvent, often under vacuum | -Simple method for EOs extraction | -Potential solvent contamination and impurities -Volatile losses during solvent evaporation -Environmental hazards from solvent waste -Extraction yield and quality depend on numerous factors (solvent type, temperature, extraction cycles, vessel design, raw materials particle size) |

| Advanced Methods | |||

| Omic-assisted hydrodistillation (OAHD)-modern route | -Electrical current passed through mixture of plant material and water -Plant material acts as resistor, converting electrical energy into heat via Joule effect -Internal heating causes release of essential oils -Oils collected through process similar to traditional HD | -Overcomes HD limitations -Rapid extraction -Minimizes volatile losses -Energy-efficient -Improved process control -Cost-effective | -Electrical conductivity concerns -Operational safety challenges -High capital investment required |

| Microwave-assisted hydrodistillation (MAHD) | -Advanced HD technique utilizing a microwave oven -Based on dielectric heating from microwaves for effective and selective heating -Modified microwave oven connected to Clevenger apparatus for lab-scale distillation -Microwave energy converted to heat energy in water due to high dielectric properties -Heat transferred to plant materials | -Rapid process | -Transition to coaxial MAHD recommended for better cost, scalability, safety, and cost-effectiveness |

| Microwave steam distillation (MSD) | -Microwave oven connected to reactor containing plant materials or standard steam distillation apparatus -Saturated steam generated and passed through plant material in microwave zone -Combination of steam and direct microwave heating causes rapid release of essential oils -Oils collected through condensation | -Effective heating -Selective extraction -High extraction efficiency -Reduced energy consumption -Reduced extraction time -Less structural alteration of chemical compounds due to lower overall heat exposure | |

| Turbo Hydrodistillation | -Mixture of water and plant materials constantly stirred at specific rpm while undergoing hydrodistillation -Agitation enhances extraction process by increasing contact between plant material and water | -Improved extraction efficiency | -Potential degradation of sensitive compounds due to intense agitation/stirring |

| Salt-Assisted Hydrodistillation | -Plant materials mixed with water and NaCl (salt) before conventional hydrodistillation -Salt alters polarity of water, potentially improving extraction efficiency | -Faster processing | -Increased processing cost and complexity |

| Enzyme-Assisted Hydrodistillation | -Plant materials mixed with water and specific enzyme -Mixture incubated at particular temperature with stirring before hydrodistillation -Enzymes break down cell walls, potentially releasing more essential oils | -Higher yields | -Salt residue removal required |

| Micelle-Mediated Hydrodistillation | -Plant materials mixed with aqueous surfactant solution (e.g., 10% Tween 40) before hydrodistillation -Surfactant forms micelles that can encapsulate essential oil components | -Milder extraction conditions than HD -Reduced or eliminated need for added water/solvents in some techniques | -High enzyme costs -Careful selection and optimization needed for different plant materials -Added chemical complexity and cost from surfactant use -Environmental concerns with surfactant disposal. |

| Solvent-Free Microwave Assisted Extraction (SFMAE) | -Plant materials placed directly in microwave extraction vessel without added solvents or water -Microwaves rapidly heat internal plant water, causing cells to expand and rupture -Released oils are vaporized, then condensed and collected | -Increased extraction kinetics compared to MAHD -Elimination of added solvents or water -Reduced risk of hydrolysis of essential oil components -Potentially higher quality of extracted oils due to minimal water interaction. | -Requires specialized microwave equipment, increasing capital costs -Potential for uneven heating and hot spots in plant material -Potential for uneven heating and hot spots in plant material |

| Microwave Hydrodiffusion and Gravity (MHG) | -Plant material subjected to microwave energy, heating internal water molecules and causing thermal stress -Leads to rupture of oil glands -EOs drain due to gravity (not evaporated) -EOs are collected at bottom of apparatus | -Improved efficiency, potentially higher quality oils -Reduced processing time and minimal water use. | -Requires specialized microwave equipment -Complex gravity drainage setup compared to traditional condensation -Risk of extract contamination if drainage not properly controlled |

| Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) | -Can be performed with or without solvents -Water or solvent added to plant material exposed to microwaves -Heated liquid penetrates plant material and extracts EOs -Liquid/EO mixture evaporated to produce concentrated EOs -Yields affected by microwave power, time, and solvent quality/quantity | -Rapid extraction -Reduced solvent consumption -High yields -Suitable for thermally sensitive compounds -Disruption of weak hydrogen bounds -Environmentally friendly -Various techniques available. | -Limited to small-scale applications -High energy consumption |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) | -Uses sound waves between 20 kHz and 2000 kHz to cause acoustic cavitation in solvent -Sound waves rupture plant cell walls releasing EOs -Can use range of solvents at temperatures from ambient to 90 °C | -Rapid extraction -Reduced solvent consumption -High yields -Suitable for thermally sensitive compounds -Disruption of weak hydrogen bounds; Environmentally friendly; Various techniques available. | -Limited to small-scale applications -High equipment cost. |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction | -Uses properties of both liquid and gaseous phase at critical point -Supercritical fluid passed through plant material repeatedly to extract EOs -Extracted EOs removed from supercritical fluid by decompression -Gas captured for reuse -Efficacy affected by matrix nature, particle size, and water content -Carbon dioxide widely used (critical conditions: 31.1 °C and 7.38 MPa) | -Rapid extraction -Selective extraction -High yields -Environmentally friendly -Low operating cost -High extraction efficiency -Fractionation capability; -Health and safety benefits of using supercritical carbon dioxide -Beneficial chemical properties such as high diffusivity, low viscosity, tunable density and dielectric constant. | -Risk of carbon dioxide retention in the operator’s blood -Challenges in high-pressure industrial operations |

| Molecular distillation | -Operates under high vacuum and low temperature -Plant extract spread in thin film on heated surface -Molecules with lower boiling points evaporate first and are collected on cooled surface -Allows separation and concentration of specific compounds | -Ability to fractionate and concentrate valuable essential oil components -Potential for high purity extracts/fractions -Mild conditions protect thermally labile compounds | -Added complexity and equipment requirements -Multiple distillation steps required -Relatively low throughput may limit scalability |

| Fractional distillation | -EOs heated in column -As temperature increases, different compounds vaporize at respective boiling points -Vapors rise through column and are collected at different levels based on volatility -Allows separation of various oil components | ||

Appendix A.2. Comparison Between Conventional and Advanced Methods of EOs Extraction

| Description | Conventional Methods | Advanced Methods |

| Methods | Hydrodistillation, steam distillation, cold pressing, solvent extraction | Microwave-assisted, ultrasound-assisted, enzyme-assisted, ohmic-assisted, membrane-assisted extraction |

| Industrial Use | Widely used, especially hydrodistillation and steam distillation | Gaining traction due to advantages over conventional methods |

| Energy Consumption | High | Generally lower |

| Extraction Efficiency | Lower | Higher |

| Extraction Rate | Slower | Faster |

| Effect on Heat-Sensitive Compounds | Can be detrimental | Generally milder, better preservation |

| Volatile Compound Loss | Potential for significant loss | Minimal loss |

| Environmental Impact | Higher (more energy, potential toxic residues) | Lower (reduced energy, less or no solvent use, lower CO2 emissions) |

| Solvent Use | Some methods require solvents | Reduced or no solvent use in many techniques |

| Selectivity | Lower | Higher selectivity for targeted compounds |

| Complexity | Simpler, well-established | More complex, may require optimization |

| Cost | Lower initial costs, but potentially higher operating costs | Higher initial costs (equipment), but potentially lower operating costs |

| Quality and Purity of EOs | Can be affected by heat and processing | Generally higher |

| Research and Development Needs | Well-established | Require more R&D for optimization |

| Flexibility | Less flexible, more standardized |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Oliveira, M.; Antunes, W.; Mota, S.; Madureira-Carvalho, Á.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; da Silva, D.D. An overview of the recent advances in antimicrobial resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallari, P.; Rostami, L.D.; Alanko, I.; Howaili, F.; Ran, M.; Bansal, K.K.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Salo-Ahen, O.M. The Next Frontier: Unveiling Novel Approaches for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Pharm. Res. 2025, 42, 859–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Vega, G.A.; Ortiz-Ramírez, J.A.; López-Romero, E. Novel Antibacterial Approaches and Therapeutic Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskovich, M.A.; Cooper, M.A. Antibiotics re-booted—Time to kick back against drug resistance. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Yarahmadi, A.; Najafiyan, H.; Yousefi, M.H.; Khosravi, E.; Shabani, E.; Afkhami, H.; Aghaei, S.S. Beyond antibiotics: Exploring multifaceted approaches to combat bacterial resistance in the modern era: A comprehensive review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1493915. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, S.T.; Rahman, A.Z.; Novomisky Nechcoff, J. Innovative perspectives on the discovery of small molecule antibiotics. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugaiyan, J.; Kumar, P.A.; Rao, G.S.; Iskandar, K.; Hawser, S.; Hays, J.P.; Mohsen, Y.; Adukkadukkam, S.; Awuah, W.A.; Jose, R.A.M.; et al. Progress in alternative strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance: Focus on antibiotics. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, K.; Murugaiyan, J.; Hammoudi Halat, D.; Hage, S.E.; Chibabhai, V.; Adukkadukkam, S.; Salameh, P.; Van Dongen, M. Antibiotic discovery and resistance: The chase and the race. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Yiap, B.C.; Ping, H.C.; Lim, S.H.E. Essential oils, a new horizon in combating bacterial antibiotic resistance. Open Microbiol. J. 2014, 8, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Lahmar, A.; Bedoui, A.; Mokdad-Bzeouich, I.; Dhaouifi, Z.; Kalboussi, Z.; Cheraif, I.; Ghedira, K.; Chekir-Ghedira, L. Reversal of resistance in bacteria underlies synergistic effect of essential oils with conventional antibiotics. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanescu, M.; Oprean, C.; Lombrea, A.; Badescu, B.A.T.; Constantin, G.D. Current State of Knowledge Regarding WHO High Priority Pathogens-Resistance Mechanisms and Proposed Solutions through Candidates Such as Essential Oils: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badescu, B.; Buda, V.; Romanescu, M.; Lombrea, A.; Danciu, C.; Dalleur, O.; Dohou, A.M.; Dumitrascu, V.; Cretu, O.; Licker, M.; et al. Current state of knowledge regarding WHO critical priority pathogens: Mechanisms of resistance and proposed solutions through candidates such as essential oils. Plants 2022, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, M.K.; Akhtar, M.S.; Sinniah, U.R. Antimicrobial Properties of Plant Essential Oils against Human Pathogens and Their Mode of Action: An Updated Review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 3012462. [Google Scholar]

- Trifan, A.; Luca, S.V.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Miron, A.; Gille, E.; Aprotosoaie, A.C. Recent advances in tackling microbial multidrug resistance with essential oils: Combinatorial and nano-based strategies. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 46, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Sharma, K.; Guleria, S. Antimicrobial Activity of Some Essential Oils—Present Status and Future Perspectives. Medicines 2017, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhara, L.; Tripathi, A. The use of eugenol in combination with cefotaxime and ciprofloxacin to combat ESBL-producing quinolone-resistant pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Dhara, L.; Tripathi, A. Cinnamaldehyde: A compound with antimicrobial and synergistic activity against ESBL-producing quinolone-resistant pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic, P.; Aleksic, V.; Simin, N.; Svircev, E.; Petrovic, A.; Mimica-Dukic, N. Antimicrobial activity of Eucalyptus camaldulensis essential oils and their interactions with conventional antimicrobial agents against multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 178, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, V.; Muselli, A.; Bernardini, A.F.; Berti, L.; Pagès, J.M.; Amaral, L. Geraniol restores antibiotic activities against multidrug-resistant isolates from gram-negative species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2209–2211. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, L.; Laird, K. Synchronous application of antibiotics and essential oils: Dual mechanisms of action as a potential solution to antibiotic resistance. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, E.O. In vitro activity of carvacrol in combination with meropenem against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Folia. Microbiol. Praha 2022, 67, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Miri, Y. Essential Oils: Chemical Composition and Diverse Biological Activities: A Comprehensive Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578X241311790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, T.; Khan, M.U.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, K. Terpenoids in essential oils: Chemistry, classification, and potential impact on human health and industry. Phytomedicine Plus 2024, 4, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mráz, P.; Kopecký, M.; Hasoňová, L.; Hoštičková, I.; Vaníčková, A.; Perná, K.; Žabka, M.; Hýbl, M. Antibacterial Activity and Chemical Composition of Popular Plant Essential Oils and Their Positive Interactions in Combination. Molecules 2025, 30, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaza, V.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Components and Their Derivatives: A Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, W.; Twardawska, M.; Grabarczyk, M.; Wińska, K. Carvacrol—A natural phenolic compound with antimicrobial properties. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coque, T.M.; Cantón, R.; Pérez-Cobas, A.E.; Fernández-de-Bobadilla, M.D.; Baquero, F. Antimicrobial resistance in the global health network: Known unknowns and challenges for efficient responses in the 21st century. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visan, D.C.; Oprea, E.; Radulescu, V.; Voiculescu, I.; Biris, I.A.; Cotar, A.I.; Saviuc, C.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Marinas, I.C. Original contributions to the chemical composition, microbicidal, virulence-arresting and antibiotic-enhancing activity of essential oils from four coniferous species. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunse, M.; Daniels, R.; Gründemann, C.; Heilmann, J.; Kammerer, D.R.; Keusgen, M. Essential Oils as Multicomponent Mixtures and Their Potential for Human Health and Well-Being. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 956541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iseppi, R.; Mariani, M.; Condò, C.; Sabia, C.; Messi, P. Essential Oils: A Natural Weapon against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Responsible for Nosocomial Infections. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, F.; Hamadeh, R.; Alameddine, M. Regulatory frameworks for a safe and effective use of essential oils: A critical appraisal. Adv. Biomed. Health Sci. 2022, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Osaili, T.M.; Dhanasekaran, D.K.; Zeb, F.; Faris, M.E.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H. A Status Review on Health-Promoting Properties and Global Regulation of Essential Oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Dai, T.; Murray, C.K.; Wu, M.X. Bactericidal Property of Oregano Oil Against Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, H.; Gousia, P.; Economou, V.; Sakkas, V.; Petsios, S.; Papadopoulou, C. In vitro antimicrobial activity of five essential oils on multidrug resistant Gram-negative clinical isolates. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, E.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pereira, M.O.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Sousa, A.M. Evolving biofilm inhibition and eradication in clinical settings through plant-based antibiofilm agents. Phytomedicine 2023, 119, 154973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, D.S.; Silva, D.B.; Frasson, A.P.; Rzhepishevska, O.; Silva, M.V. LPE Natural Green coating inhibits adhesion of clinically important bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8287. [Google Scholar]

- Zouirech, O.; Alyousef, A.A.; El Barnossi, A.; El Moussaoui, A.; Bourhia, M.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Ouahmane, L.; Giesy, J.P.; Aboul-Soud, M.A.M.; Lyoussi, B.; et al. Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal effects of essential oil of black caraway (Nigella sativa L.) seeds against drug-resistant clinically pathogenic microorganisms. BioMed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5218950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafa, A.H.T.; Aslan, R.; Celik, C.; Hasbek, M. Antimicrobial synergism and antibiofilm activities of Pelargonium graveolens, Rosemary officinalis, and Mentha piperita essential oils against extreme drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Z. Für Naturforschung C 2022, 77, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Vasireddy, L.; Bingle, L.E.H.; Davies, M.S. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201835. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Shokoohizadeh, L.; Zare Fahim, N.; Mohamadi Bardebari, A.; Moradkhani, S.; Alikhani, M.Y. Detection of adeABC efllux pump encoding genes and antimicrobial effect of Mentha longifolia and Menthol on MICs of imipenem and ciprofloxacin in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magi, G.; Marini, E.; Facinelli, B. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and carvacrol, and synergy of carvacrol and erythromycin, against clinical, erythromycin-resistant Group A Streptococci. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibi, S.; Ben Selma, W.; Ramos-Vivas, J.; Smach, M.A.; Touati, R.; Boukadida, J. Anti-oxidant, antibacterial, anti-biofilm, and anti-quorum sensing activities of four essential oils against multidrug-resistant bacterial clinical isolates. Curr. Res. Transl. Med. 2020, 68, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Wani, S.; Rasool, W.; Shafi, K.; Bhat, M.A.; Prabhakar, A.; Shalla, A.H.; Rather, M.A. A comprehensive review of the antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents against drug-resistant microbial pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 134, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentzer, M.; Wu, H.; Andersen, J.B.; Riedel, K.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Bagge, N. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 3803–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents—How P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 3, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichling, J. Anti-biofilm and virulence factor-reducing activities of essential oils and oil components as a possible option for bacterial infection control. Planta. Med. 2020, 86, 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.C.; Zhu, R.X.; Jia, L.R.; Gao, H.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Q. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oil from Gnaphlium affine. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Romero, J.C.; González-Ríos, H.; Borges, A.; Simões, M. Antibacterial effects and mode of action of selected essential oils components against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 795435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.O.; Holley, R.A. Inhibition of membrane bound ATPases of Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes by plant oil aromatics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z. Effect of thyme essential oil against Bacillus cereus planktonic growth and biofilm formation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 10209–10218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Anda Jd Baker, A.E.; Bennett, R.R.; Luo, Y.; Lee, E.Y. Multigenerational memory and adaptive adhesion in early bacterial biofilm communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4471–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrustera, C.R.; Parsek, M.R. New insight into the early stages of biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4317–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, T.B.; Givskov, M. Quorum sensing inhibitors: A bargain of effects. Microbiology 2006, 152, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, M.; Hidalgo, W.; Stashenko, E.E.; Torres, R.; Ortiz, C. Metabolomic Analysis of the Effect of Lippia origanoides Essential Oil on the Inhibition of Quorum Sensing in Chromobacterium violaceum. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.B.; Kragh, K.N.; Hultqvist, L.D.; Rybtke, M.; Nilsson, M.; Jakobsen, T.H. Induction of native c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases leads to dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02431-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, P.P.; Suresh, S.; Nanjappa, D.P.; James, J.P.; Kaverikana, R.; Chakraborty, A. Isolation and identification of quorum sensing antagonist from Cinnamomum verum leaves against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Life Sci. 2021, 267, 118878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambyal, S.S.; Sharma, P.; Shrivastava, D. Anti-biofilm Activity of Selected Plant Essential Oils against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumi, E.; Merghni, A.; Alreshidi, M.; Haddad, O.; Akmadar, G.; De Martino, L.; Mastouri, M.; Ceylan, O.; Snoussi, M.; Al-Sieni, A.; et al. Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: Models for Evaluating Anti-Quorum Sensing Activity of Melaleuca alternifolia Essential Oil and Its Main Component Terpinen-4-ol. Molecules 2018, 23, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wei, P.W.; Wan, S.; Yao, Y.; Song, C.R.; Song, P.P. Ginkgo biloba exocarp extracts inhibit S. aureus and MRSA by disrupting biofilms and affecting gene expression. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 271, 113895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisuria, V.B.; Hosseinidoust, Z.; Tufenkji, N. Polyphenolic extract from maple syrup potentiates antibiotic susceptibility and reduces biofilm formation of pathogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3782–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, H.; Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, I. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of some essential oils and compounds against clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biomed. Ther. Sci. 2014, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tullio, V.; Roana, J.; Cavallo, L.; Mandras, N. Immune defences: A view from the side of the essential oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandner, G.; Heckmann, M.; Weghuber, J. Immunomodulatory activities of selected essential oils. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazul, M.; Kwiatkowski, P.; Hartman, K.; Kilanowicz, A.; Sienkiewicz, M. How to naturally support the immune system in inflammation—Essential oils as immune boosters. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafino, A.; Vallebona, P.S.; Andreola, F.; Zonfrillo, M.; Mercuri, L.; Federici, M.; Rasi, G.; Garaci, E.; Pierimarchi, P. Stimulatory effect of Eucalyptus essential oil on innate cell-mediated immune response. BMC Immunol. 2008, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterfalvi, A.; Miko, E.; Nagy, T.; Reger, B.; Simon, D.; Miseta, A.; Czéh, B.; Szereday, L. Much more than a pleasant scent: A review on essential oils supporting the immune system. Molecules 2019, 24, 4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Abrini, J.; Dakka, N.; Bakri, Y. Essential oils of Origanum compactum increase membrane permeability, disturb cell membrane integrity, and suppress quorum-sensing phenotype in bacteria. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 9, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Chamkhi, I.; Balahbib, A.; Rebezov, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Wilairatana, P.; Mubarak, M.S.; Benali, T.; El Omari, N. Mechanisms, anti-quorum-sensing actions, and clinical trials of medicinal plant bioactive compounds against bacteria: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Niu, X.; Li, D.; Yang, C. Antibacterial activity and anti-quorum sensing mediated phenotype in response to essential oil from Melaleuca bracteata leaves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.Y.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, K.J. Artemisia princeps inhibits biofilm formation and virulence-factor expression of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. BioMed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 239519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.A.; Zahin, M.; Hasan, S.; Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, I. Inhibition of quorum sensing regulated bacterial functions by plant essential oils with special reference to clove oil. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 49, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, I.; Asif, M.; Tahseen, Q. Influence of clove oil on certain quorum-sensing-regulated functions and biofilm of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Biosci. 2013, 38, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, E.; Tahseen, Q.; Khan, M.S.; Alshabib, N. Sub-MICs of Mentha piperita essential oil and menthol inhibits AHL mediated quorum sensing and biofilm of Gram-negative bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Viljoen, A.M.; Chenia, H.Y. The impact of plant volatiles on bacterial quorum sensing. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelz, Z.; Molnar, J.; Hohmann, J. Antimicrobial and antiplasmid activities of essential oils. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemaiswarya, S.; Soudaminikkutty, R.; Narasumani, M.L.; Doble, M. Phenylpropanoids inhibit protofilament formation of Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsZ. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, P.; Koščová, J. In vitro antibacterial activity of Mentha essential oils against Staphylococcus aureus. Folia. Vet. 2017, 61, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, L.H.; Wang, M.S.; Zeng, X.A.; Gong, D.-M.; Huang, Y.-B. An in vitro investigation of the inhibitory mechanism of β-galactosidase by cinnamaldehyde alone and in combination with carvacrol and thymol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1861, 3189–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, S.; Dwivedi, G.R.; Darokar, M.P.; Kalra, A.; Khanuja, S.P. Potential of rosemary oil to be used in drug-resistant infections. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2007, 13, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, M.; Jovanović, K.K.; Marković, T.; Marković, D.; Gligorijević, N.; Radulović, S.; Soković, M. Chemical composition, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic properties of five Lamiaceae essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 61, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquila, P.; Paparazzo, E.; Crudo, M.; Bonacci, S.; Procopio, A.; Passarino, G.; Bellizzi, D. Antibacterial activity and epigenetic remodeling of essential oils from calabrian aromatic plants. Nutrients 2022, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivieso-Ugarte, M.; Gomez-Llorente, C.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Gil, A. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Immunomodulatory Properties of Essential Oils: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Yap, P.S.X.; Krishnan, T.; Yusoff, K.; Chan, K.G.; Yap, W.S.; Lai, K.-S.; Lim, S.-H.E. Mode of action: Synergistic interaction of peppermint [Mentha × piperita L. Carl] essential oil and meropenem against plasmid-mediated resistant E. coli. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2018, 12, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puškárová, A.; Bučková, M.; Kraková, L.; Pangallo, D.; Kozics, K. The antibacterial and antifungal activity of six essential oils and their cyto/genotoxicity to human HEL 12469 cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zani, F.; Massimo, G.; Benvenuti, S.; Bianchi, A.; Albasini, A.; Melegari, M.; Vampa, G.; Bellotti, A.; Mazza, P. Studies on the genotoxic properties of essential oils with Bacillus subtilis rec-assay and Salmonella/microsome reversion assay. Planta Medica 1991, 57, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.S.Y.; Maran, S.; Yap, P.S.X.; Lim, S.H.E.; Yang, S.K.; Cheng, W.H.; Tan, Y.-H.; Lai, K.-S. Anti-and pro-oxidant properties of essential oils against antimicrobial resistance. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Yusoff, K.; Ajat, M.; Thomas, W.; Abushelaibi, A.; Akseer, R. Disruption of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae membrane via induction of oxidative stress by cinnamon bark [Cinnamomum verum J. Presl] essential oil. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowbe, K.H.; Salah, K.B.H.; Moumni, S.; Ashkan, M.F.; Merghni, A. Anti-staphylococcal activities of rosmarinus officinalis and myrtus communis essential oils through ROS-mediated oxidative stress. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Walmsley, M.I.; McKeegan, K.S.; Walmsley, A.R. Structure and function of efflux pumps that confer resistance to drugs. Biochem. J. 2003, 376, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coșeriu, R.L.; Vintilă, C.; Pribac, M.; Mare, A.D.; Ciurea, C.N.; Togănel, R.O.; Simion, A.; Man, A. Antibacterial Effect of 16 Essential Oils and Modulation of mex Efflux Pumps Gene Expression on Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates: Is Cinnamon a Good Fighter? Antibiotics 2023, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazy, R. Identification of Potential Therapeutics of Mentha Essential Oil Content as Antibacterial MDR Agents against AcrAB-TolC Multidrug Efflux Pump from Escherichia coli: An In Silico Exploration. Life 2024, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.S.; Sobkowiak, B.; Parreira, R.; Edgeworth, J.D.; Viveiros, M.; Clark, T.G.; Couto, I. Genetic diversity of norA, coding for a main efflux pump of Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, A.; Doulabi, M.S.H.; Sohrabnia, B.; Jalali, A. The effect of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) extract on the expression of norA efflux pump gene in clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Genet. Resour. 2018, 4, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, O.; Sharifi, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Nayeri Fasaei, B. Antibacterial and anti-PmrA activity of plant essential oils against fluoroquinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baky, R.M.A.; Hashem, Z.S. Eugenol and linalool: Comparison of their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 10, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherf, J.R.; Dos Santos, C.R.B.; Freitas, T.S.; Rocha, J.E.; Macêdo, N.S.; Lima, J.N.M.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; da Cunha, F.A.B. Effect of terpinolene against the resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain, carrier of the efflux pump QacC and β-lactamase gene, and its toxicity in the Drosophila melanogaster model. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, Y.J.; Saadedin, S.M.K. Pharmaceutical Design Using a Combination of Cephalosporin Antibiotic and Ginger Essential Oil as Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors Against UTI Escherichia coli. Revis. Bionatura 2021, 7, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, G.H.D.A.; Santos Radai, J.A.; Mattos Vaz, M.S.; Silva, K.; Fraga, T.L.; Barbosa, L.S.; Simionatto, S. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity assays of carvacrol: A candidate for development of innovative treatments against KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 0246003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, L.; Rasco, B.; Zhu, M.J. Cinnamon oil inhibits Shiga toxin type 2 phage induction and Shiga toxin type 2 production in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6531–6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaralleh, H. Thymol rich Thymbra capitata essential oil inhibits quorum sensing, virulence and biofilm formation of beta lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2019, 25, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Arsi, K.; Wagle, B.R.; Upadhyaya, I.; Shrestha, S.; Donoghue, A.M.; Donoghue, D.J. Trans-cinnamaldehyde, carvacrol, and eugenol reduce Campylobacter jejuni colonization factors and expression of virulence genes in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, S.A.; van der Zee, R.; Koets, A.P.; de Graaff, A.M.; van Knapen, F.; Gaastra, W.; Haagsman, H.P.; Veldhuizen, E.J.A. Carvacrol induces heat shock protein 60 and inhibits synthesis of flagellin in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4484–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.C.; Meireles, L.M.; Lemos, M.F.; Guimarães, M.C.C.; Endringer, D.C.; Fronza, M. Antibacterial Activity of Terpenes and Terpenoids Present in Essential Oils. Molecules 2019, 24, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, S.; Rtibi, K.; Hosni, K.; Sebai, H. Essential Oil, Chemical Compositions, and Therapeutic Potential. In Essential Oils-Advances in Extractions and Biological Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential oils: Chemistry and pharmacological activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahizan, N.A.; Yang, S.K.; Moo, C.L.; Song, A.A.L.; Chong, C.M.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.E.; Lai, K.S. Terpene derivatives as a potential agent against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pathogens. Molecules 2019, 24, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, M.; Stien, D.; Eparvier, V.; Ouaini, N.; El Beyrouthy, M. Report on the Medicinal Use of Eleven Lamiaceae Species in Lebanon and Rationalization of Their Antimicrobial Potential by Examination of the Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Their Essential Oils. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2547169. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, R.; Hanif, M.A.; Mushtaq, Z.; Al-Sadi, A.M. Biosynthesis of essential oils in aromatic plants: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2016, 32, 117–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosari, F.; Taheri, M.; Moradi, A.; Hakimi Alni, R.; Alikhani, M.Y. Evaluation of cinnamon extract effects on clbB gene expression and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli strains isolated from colon cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelatti, M.A.I.; Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; El-Naenaeey, E.Y.M.; Ammar, A.M.; Alharbi, N.K.; Alharthi, A. Antibacterial and Anti-Efflux Activities of Cinnamon Essential Oil against Pan and Extensive Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Human and Animal Sources. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1514. [Google Scholar]

- Foda, A.M.; Kalaba, M.H.; El-Sherbiny, G.M.; Moghannem, S.A.; El-Fakharany, E.M. Antibacterial activity of essential oils for combating colistin-resistant bacteria. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Utchariyakiat, I.; Surassmo, S.; Jaturanpinyo, M.; Khuntayaporn, P.; Chomnawang, M.T. Efficacy of cinnamon bark oil and cinnamaldehyde on anti-multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the synergistic effects in combination with other antimicrobial agents. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, N.G.; Queiroz, J.H.F.d.S.; da Silva, K.E.; Vasconcelos, P.C.d.P.; Croda, J.; Simionatto, S. Synergistic effects of Cinnamomum cassia L. essential oil in combination with polymyxin B against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Serratia marcescens. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236505. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, N.G.; Silva, K.E.; Croda, J.; Simionatto, S. Antibacterial activity of Cinnamomum cassia L. essential oil in a carbapenem-and polymyxin-resistant Klebsiella aerogenes strain. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2020, 53, e20200032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbestawy, M.K.M.; El-Sherbiny, G.M.; Moghannem, S.A. Antibacterial, Antibiofilm and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Eugenol Clove Essential Oil against Resistant Helicobacter pylori. Molecules 2023, 28, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, J.K.; Felső, P.; Makszin, L.; Pápai, Z.; Horváth, G.; Ábrahám, H. Antimicrobial and Virulence-Modulating Effects of Clove Essential Oil on the Foodborne Pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6158–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, F.; Oliva, A.; Sabatino, M.; Imbriano, A.; Hanieh, P.N.; Garzoli, S.; Mastroianni, C.M.; De Angelis, M.; Miele, M.C.; Arnaut, M.; et al. Antimicrobial Essential Oil Formulation: Chitosan Coated Nanoemulsions for Nose to Brain Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeka, L.B.; Emeka, P.M.; Khan, T.M. Antimicrobial activity of Nigella sativa L. seed oil against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from diabetic wounds. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 28, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ugur, A.R.; Dagi, H.T.; Ozturk, B.; Tekin, G.; Findik, D. Assessment of in vitro antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity effect of Nigella sativa oil. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2016, 12, S471–S474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scazzocchio, F.; Mondì, L.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Goldoni, P.; Comanducci, A.; Marazzato, M. Coriander [Coriandrum sativum]. Essential Oil: Effect on Multidrug Resistant Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenati, F.; Benbelaid, F.; Khadir, A.; Bellahsene, C.; Bendahou, M. Antimicrobial effects of three essential oils on multidrug resistant bacteria responsible for urinary infections. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 4, 015–018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M.; Poznańska-Kurowska, K.; Kaszuba, A.; Kowalczyk, E. The antibacterial activity of geranium oil against Gram-negative bacteria isolated from difficult-to-heal wounds. Burns 2014, 40, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shouny, W.A.; Ali, S.S.; Sun, J.; Samy, S.M.; Ali, A. Drug resistance profile and molecular characterization of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESβL)-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from burn wound infections. Essential oils and their potential for utilization. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 116, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosakueng, M.; Taweechaisupapong, S.; Boonyanugomol, W.; Prapatpong, P.; Wongkaewkhiaw, S.; Kanthawong, S. Cymbopogon citratus L. essential oil as a potential anti-biofilm agent active against antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Biofouling 2024, 40, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, B.; Balázs, V.L.; Molnár, S.; Szögi-Tatár, B.; Böszörményi, A.; Palkovics, T.; Horváth, G.; Schneider, G. Antibacterial Effect of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) against the Aetiological Agents of Pitted Keratolyis. Molecules 2022, 27, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntean, D.; Licker, M.; Alexa, E.; Popescu, I.; Jianu, C.; Buda, V.; Dehelean, C.A.; Ghiulai, R.; Horhat, F.; Horhat, D.; et al. Evaluation of essential oil obtained from Mentha × piperita L. against multidrug-resistant strains. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2905–2914. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, N.G.; Croda, J.; Silva, K.E.; Motta, M.L.L.; Maciel, W.G.; Limiere, L.C.; Simionatto, S. Origanum vulgare L. essential oil inhibits the growth of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, S.C.; Pruski, B.B.; De Freitas, S.B.; Allend, S.O.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Moreira, C.; Pereira, D.I.B.; Junior, A.S.V.; Hartwig, D.D. Origanum vulgare essential oil: Antibacterial activities and synergistic effect with polymyxin B against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 9615–9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J. Carvacrol-rich oregano oil and thymol-rich thyme red oil inhibit biofilm formation and the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskatepe, B.; Yildiz, S.S.; Kiymaci, M.E.; Yazgan, A.N.; Cesur, S.; Erdem, S.A. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the commercial Origanum onites L. oil against nosocomial carbapenem resistant extended spectrum beta lactamase producer Escherichia coli isolates. Acta Biol. Hung. 2017, 68, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksić, A.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.; Harmanus, C.; Kuijper, E.J.; Stojanović, P. In vitro anti-clostridial action and potential of the spice herbs essential oils to prevent biofilm formation of hypervirulent Clostridioides difficile strains isolated from hospitalized patients with CDI. Anaerobe 2022, 76, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zuhairi, J.J.M.J.; Kashi, F.J.; Rahimi-Moghaddam, A.; Yazdani, M. Antioxidant, cytotoxic and antibacterial activity of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil against bacteria isolated from urinary tract infection. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 38, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagha, R.; Ben Abdallah, F.; Al-Sarhan, B.O.; Al-Sodany, Y. Antibacterial and biofilm inhibitory activity of medicinal plant essential oils against Escherichia coli isolated from UTI patients. Molecules 2019, 24, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, R.R.; Putsathit, P.; Tai, A.S.; Hammer, K.A. Antimicrobial effects of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) essential oil against biofilm-forming multidrug-resistant cystic fibrosis-associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a single agent and in combination with commonly nebulized antibiotics. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 75, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Vishakha, K.; Banerjee, S.; Nag, D.; Ganguli, A. Exploring the antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antivirulence activities of tea tree oil-containing nanoemulsion against carbapenem-resistant Serratia marcescens associated infections. Biofouling 2022, 38, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouguenoun, W.; Benbelaid, F.; Mebarki, S.; Bouguenoun, I.; Boulmaiz, S.; Khadir, A.; Benziane, M.Y.; Bendahou, M.; Muselli, A. Selected antimicrobial essential oils to eradicate multi-drug resistant bacterial biofilms involved in human nosocomial infections. Biofouling 2023, 39, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, A.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Zahraei Salehi, T.; Mahmoodi, P. Antibacterial, antibiofilm and antiquorum sensing effects of Thymus daenensis and Satureja hortensis essential oils against Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maida, I.; Lo Nostro, A.; Pesavento, G.; Barnabei, M.; Calonico, C.; Perrin, E. Exploring the Anti-Burkholderia cepacia Complex Activity of Essential Oils: A Preliminary Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 573518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, N.G.; Mallmann, V.; Costa, É.R.; Simionatto, E.; Coutinho, E.J.; Silva, R.C. Antibacterial activity and synergism of the essential oil of Nectandra megapotamica [L.] flowers against OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2020, 32, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovanová, R.; Mezovská, J.; Vaverková, Š.; Mikulášová, M. The inhibition the Tet(K) efflux pump of tetracycline resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis by essential oils from three Salvia species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejčić, M.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.; Genčić, M.; Dimitrijević, M.; Radulović, N. Anti-virulence potential of basil and sage essential oils: Inhibition of biofilm formation, motility and pyocyanin production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 141, 111431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.d.S.; Pereira, R.L.S.; dos Santos, A.T.L.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Morais-Braga, M.F.B.; da Silva, V.B.; Costa, A.R.; Generino, M.E.M.; de Oliveira, M.G.; de Menezes, S.A.; et al. Phytochemical Analysis, Antibacterial Activity and Modulating Effect of Essential Oil from Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels. Molecules 2022, 27, 3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekka-Hadji, F.; Bombarda, I.; Djoudi, F.; Bakour, S.; Touati, A. Chemical composition and synergistic potential of Mentha pulegium L. and Artemisia herba alba Asso. essential oils and antibiotic against multi-drug resistant bacteria. Molecules 2022, 27, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseppi, R.; Di Cerbo, A.; Aloisi, P.; Manelli, M.; Pellesi, V.; Provenzano, C.; Camellini, S.; Messi, P.; Sabia, C. In Vitro Activity of Essential Oils Against Planktonic and Biofilm Cells of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)/Carbapenamase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria Involved in Human Nosocomial Infections. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Yusoff, K.; Mai, C.W.; Lim, W.M.; Yap, W.S.; Lim, S.H.E.; Lai, K.-S. Additivity vs. synergism: Investigation of the additive interaction of cinnamon bark oil and meropenem in combinatory therapy. Molecules 2017, 22, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, M.; Yadav, V.K.; Singh, P.K.; Sharma, D.; Pandey, H.; Narvi, S.S. Effect of Cinnamon Oil on Quorum Sensing-Controlled Virulence Factors and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.I.; Baek, K.H.; Lee, J. Cinnamon bark oil and its components inhibit biofilm formation and toxin production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 195, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, G.K.; Feiria, S.B.; Maia, F.C.; Oliveira, T.R.; Joia, F.; Barbosa, J.P. In-vitro Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Cinnamomum verum Leaf Oil against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2021, 93, e20201507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Atki, Y.; Aouam, I.; El Kamari, F.; Taroq, A.; Nayme, K.; Timinouni, M.; Lyoussi, B.; Abdellaoui, A. Antibacterial activity of cinnamon essential oils and their synergistic potential with antibiotics. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2019, 10, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.; Krishnan, T.; Chan, K.G.; Lim, S.H. Antibacterial Mode of Action of Cinnamomum verum Bark Essential Oil, Alone and in Combination with Piperacillin, Against a Multi-Drug-Resistant Escherichia coli Strain. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1299–1306. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25381741/ (accessed on 23 September 2024). [PubMed]

- Man, A.; Santacroce, L.; Jacob, R.; Mare, A.; Man, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Six Essential Oils Against a Group of Human Pathogens: A Comparative Study. Pathogens 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sayed, E.; Gad, H.A.; El-Kersh, D.M. Characterization of Four Piper Essential Oils [GC/MS and ATR-IR] Coupled to Chemometrics and Their anti-Helicobacter pylori Activity. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 25652–25663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, A.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Franchini, C.; Corbo, F. Elucidation of the synergistic action of Mentha piperita essential oil with common antimicrobials. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Pruss, A.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Wojciuk, B.; Dołęgowska, B.; Giedrys-Kalemba, S. Preliminary Study on the Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils Alone and in Combination with Gentamicin Against Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing and New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase-1-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Gong, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Chi, F. Rosemary and Tea Tree Essential Oils Exert Antibiofilm Activities In Vitro against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, K.B.; Tiwari, A.; Gaikwad, S.; Kore, S.; Nawani, N.; Wani, M.; Swamy, K.V.; Pawar, S.V. Computational docking investigation of phytocompounds from bergamot essential oil against Serratia marcescens protease and FabI: Alternative pharmacological strategy. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2023, 104, 107829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leja, K.; Szudera-Kończal, K.; Świtała, E.; Juzwa, W.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Czaczyk, K. The influence of selected plant essential oils on morphological and physiological characteristics in Pseudomonas orientalis. Foods 2019, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Velázquez, N.G.; Gomez-Valdez, A.A.; González-Ávila, M.; Sánchez-Navarrete, J.; Toscano-Garibay, J.D.; Ruiz-Pérez, N.J. Preliminary study on citrus oils antibacterial activity measured by flow cytometry: A step-by-step development. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Mas, M.C.; Rambla, J.L.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Blázquez, M.A.; Granell, A. Volatile compounds in citrus essential oils: A comprehensive review. Front. Plant. Sci. 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvand, Z.M.; Parseghian, L.; Aliahmadi, A.; Rahimi, M.; Rafati, H. Nanoencapsulated Thymus daenensis and Mentha piperita essential oil for bacterial and biofilm eradication using microfluidic technology. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 651, 123751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisserand, R. Essential Oil Safety: A Guide for Health Care Professionals, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alvand, Z.M.; Rahimi, M.; Rafati, H. A microfluidic chip for visual investigation of the interaction of nanoemulsion of Satureja Khuzistanica essential oil and a model gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 607, 121032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Armas, J.; Arroyo-Acevedo, J.; Ortiz-Sánchez, M.; Palomino-Pacheco, M.; Castro-Luna, A.; Ramos-Cevallos, N. Acute and Repeated 28-Day Oral Dose Toxicity Studies of Thymus vulgaris L. Essent. Oil Rats. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 35, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, S.D.; Sharma, B. Medicinal plants in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2004, 120, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Raptis, V.; Karatasos, K. Molecular dynamics simulations of essential oil ingredients associated with hyperbranched polymer drug carriers. Polymers 2022, 14, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbashi, A.S.; Garbi, M.I.; Osman, E.E.; Dahab, M.M.; Koko, W.S.; Abuzeid, N. In vitro antimicrobial activity of ethanolic seeds extract of Nigella sativa (Linn) in Sudan. AJMR 2015, 9, 788–792. [Google Scholar]

- Manju, S.; Malaikozhundan, B.; Vijayakumar, S.; Shanthi, S.; Jaishabanu, A.; Ekambaram, P. Antibacterial, antibiofilm and cytotoxic effects of Nigella sativa essential oil coated gold nanoparticles. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 91, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafhal, S.; Vanloot, P.; Bombarda, I.; Valls, R.; Kister, J.; Dupuy, N. Raman spectroscopy for identification and quantification analysis of essential oil varieties: A multivariate approach applied to lavender and lavandin essential oils. J. Raman. Spectrosc. 2015, 46, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović-Balaban, Ž.; Stanojević, L.; Kalaba, V.; Stanojević, J.; Cvetković, D.; Cakić, M. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oil of Menthae piperitae L. Life 2018, 9, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wińska, K.; Mączka, W.; Łyczko, J.; Grabarczyk, M.; Czubaszek, A.; Szumny, A. Essential oils as antimicrobial agents—Myth or real alternative? Molecules 2019, 24, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facanali, R.; Marques, M.O.M.; Hantao, L.W. Metabolic Profiling of Varronia curassavica Jacq. Terpenoids by Flow Modulated Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. Separations 2020, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.J.; Ng, E.V.; Yang, S.K.; Moo, C.L.; Low, W.Y.; Yap, P.S.X. Transcriptomic analysis of multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli K-12 strain in response to Lavandula angustifolia essential oil. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.P.; de Castro Melo, E.; Barbosa, L.C.A.; dos Santos, H.S.; Cecon, P.R.; Dallacort, R. Influence of plant age on the content and composition of essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus [DC.] Stapf. JMPR 2014, 8, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ebrahimzadeh, H.; Niknam, V.; Zahed, Z. Age-dependent responses in cellular mechanisms and essential oil production in sweet Ferula assafoetida under prolonged drought stress. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, K.A.; Carson, C.F.; Riley, T.V. Effects of Melaleuca alternifolia [Tea Tree] Essential Oil and the Major Monoterpene Component Terpinen-4-ol on the Development of Single- and Multistep Antibiotic Resistance and Antimicrobial Susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houdkova, M. New broth microdilution volatilization method for antibacterial susceptibility testing of volatile agents and evaluation of their toxicity using modified MTT assay in vitro. Molecules 2021, 26, 4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajic, I.; Kabic, J.; Kekic, D.; Jovicevic, M.; Milenkovic, M.; Mitic Culafic, D.; Trudic, A.; Ranin, L.; Opavski, N. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: A comprehensive review of currently used methods. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Zheng, F.; He, S. Failure of Staphylococcus aureus to Acquire Direct and Cross Tolerance after Habituation to Cinnamon Essential Oil. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Yusoff, K.; Thomas, W.; Akseer, R.; Alhosani, M.S.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lim, S.-H.-E.; Lai, K.-S. Lavender essential oil induces oxidative stress which modifies the bacterial membrane permeability of carbapenemase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Nebija, D.; Kashtanjeva, A.; Widelski, J.; Glowniak, K.; Guettou, B.; Rahal, K.; Gruľová, D.; Dugo, G.; et al. Essential oil composition and variability of Hypericum perforatum L. from wild population in Kosovo. Curr. Issues Pharm. Med. Sci. 2014, 27, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asbahani, A.; Jilale, A.; Voisin, S.N.; Aït Addi, E.H.; Casabianca, H.; El Mousadik, A.; Hartmann, D.J.; Renaud, F.N. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of nine essential oils obtained by steam distillation of plants from the Souss-Massa Region (Morocco). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015, 27, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.I.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, J. Anti-biofilm, anti-hemolysis, and anti-virulence activities of black pepper, cananga, myrrh oils, and nerolidol against Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 9447–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokou, J.B.H.; Dongmo, P.M.J.; Boyom, F.F. Essential oil’s chemical composition and pharmacological properties. In Essential Oils-Oils of Nature; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benkova, M.; Soukup, O.; Marek, J. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Currently used methods and devices and the near future in clinical practice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulankova, R. Methods for Determination of Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils In Vitro—A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Lukowicz, R.; Merchant, S.; Valquier-Flynn, H.; Caballero, J.; Sandoval, J.; Okuom, M.; Huber, C.; Brooks, T.D.; Wilson, E.; et al. Quantitative and qualitative assessment methods for biofilm growth: A mini-review. Res. Rev. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Xu, D.; Zhang, H.; Qian, J.; Yang, Q. Transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses reveal the differential accumulation of phenylpropanoids between Cinnamomum cassia Presl and Cinnamomum cassia Presl var. macrophyllum Chu. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 148, 112282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Huang, M.; Pang, Y.X.; Yu, F.L.; Chen, C.; Liu, L.W. Variations in Essential Oil Yield, Composition, and Antioxidant Activity of Different Plant Organs from Blumea balsamifera [L.] DC Differ Growth Times. Molecules 2016, 21, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R.; Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Szymczak, G. Volatile constituents of Melissa officinalis leaves determined by plant age. Nat. Prod Commun. 2014, 9, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G.; Rajivgandhi, G.N.; Murugan, S.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Almanaa, T.N.; Manoharan, N.; Li, W.-J. Anti-carbapenamase activity of Camellia japonica essential oil against isolated carbapenem resistant klebsiella pneumoniae (MN396685). Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampasakali, E.; Nakas, A.; Mertzanidis, D.; Kokkini, S.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Christofilos, D. μ-Raman Determination of Essential Oils’ Constituents from Distillates and Leaf Glands of Origanum Plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, R.K.; Shulaev, V. Metabolomics technology and bioinformatics for precision medicine. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1957–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.N.; Alves, F.C.B.; Andrade, B.F.M.T.; Albano, M.; Rall, V.L.M.; Fernandes, A.A.H.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Leite, A.d.L.; de Pontes, L.G.; dos Santos, L.D.; et al. Proteomic analysis and antibacterial resistance mechanisms of Salmonella Enteritidis submitted to the inhibitory effect of Origanum vulgare essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J. Proteom. 2020, 214, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, W.; Ali, Q.; Ahmed, S. Microscopic visualization of the antibiofilm potential of essential oils against Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 3921–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.H.; Gwon, G.; Kim, S.I.; Park, J.G.; Lee, J. Essential Oils and Eugenols Inhibit Biofilm Formation and the Virulence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, H.A.; Sadek, Z.; Edris, A.E.; Saad-Hussein, A. Analysis and antibacterial activity of Nigella sativa essential oil formulated in microemulsion system. J. Oleo. Sci. 2015, 64, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofa, A. Antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains of swine origin: Molecular typing and susceptibility to oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) essential oil and maqui (Aristotelia chilensis (Molina) Stuntz) extract. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Z.A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Setapar, S.H.M.; Karakucuk, A.; Azim, M.M.; Lokhat, D. Essential Oils: Extraction Techniques. Pharm. Ther. Potential.-Rev. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Mohammadzadeh, A. Streptococcus pneumoniae quorum sensing and biofilm formation are affected by Thymus daenensis, Satureja hortensis, and Origanum vulgare essential oils. Acta. Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2018, 65, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Costantini, S.; Angelis, M.; Garzoli, S.; Božović, M.; Mascellino, M.T.; Vullo, V.; Ragno, R. High potency of melaleuca alternifolia essential oil against multi-drug resistant gram-negative bacteria and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2018, 23, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abers, M.; Schroeder, S.; Goelz, L.; Sulser, A.; Rose, T.; Puchalski, K.; Langland, J. Antimicrobial activity of the volatile substances from essential oils. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, Y.X. Plant essential oils as active antimicrobial agents. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A. Volatile phenolics: A comprehensive review of the anti-infective properties of an important class of essential oil constituents. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Lucy, I.B. Conventional methods and future trends in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, T.J. Methods for screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity: A review of protocols, advantages, and limitations. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 14, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatroudi, A. Investigating Biofilms: Advanced Methods for Comprehending Microbial Behavior and Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2024, 29, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Krishnan, T.; Yiap, B.C.; Hu, C.P.; Chan, K.G.; Lim, S.H.E. Membrane disruption and anti-quorum sensing effects of synergistic interaction between Lavandula angustifolia [lavender oil] in combination with antibiotic against plasmid-conferred multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouwakeh, A.; Kincses, A.; Nové, M.; Mosolygó, T.; Mohácsi-Farkas, C.; Kiskó, G. Nigella sativa essential oil and its bioactive compounds as resistance modifiers against Staphylococcus aureus. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, P.; Bernabè, G.; Filippini, R.; Piovan, A. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activities of Commercially Available Tea Tree [Melaleuca alternifolia] Essential Oils. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.; Luís, Â.; Oleastro, M.; Domingues, F.C. Antioxidant properties of coriander essential oil and linalool and their potential to control Campylobacter spp. Food Control 2016, 61, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvand, Z.M.; Rahimi, M.; Rafati, H. Chitosan decorated essential oil nanoemulsions for enhanced antibacterial activity using a microfluidic device and response surface methodology. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, T.D.S.; Costa, J.M.A.R.; Ribeiro, F.D.O.S.; Jesus Oliveira, A.C.; Nascimento Dias, J.; Araujo, A.R.; Barros, A.B.; Brito, M.d.P.; de Oliveira, T.M.; de Almeida, M.P.; et al. Nanoemulsion of cashew gum and clove essential oil (Ocimum gratissimum Linn) potentiating antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharbach, M.; Marmouzi, I.; El JemLi, M.; Bouklouze, A.; Vander Heyden, Y. Recent advances in untargeted and targeted approaches applied in herbal-extracts and essential-oils fingerprinting—A review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 177, 112849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriani, A.; Fortinguerra, S.; Sorrenti, V.; Caudullo, G.; Carrara, M. Essential Oil Phytocomplex Activity, a Review with a Focus on Multivariate Analysis for a Network Pharmacology-Informed Phytogenomic Approach. Molecules 2020, 25, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, F.; Frascella, A.; Semenzato, G.; Del Duca, S.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; Mocali, S. Employing Genome Mining to Unveil a Potential Contribution of Endophytic Bacteria to Antimicrobial Compounds in the Origanum vulgare L. Essent. Oil Antibiot. Basel 2023, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Yang, H. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal the adaptive responses of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to thyme and cinnamon oils. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.K.; Tan, N.P.; Chong, C.W.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lim, S.H.E.; Lai, K.S. The Missing Piece: Recent Approaches Investigating the Antimicrobial Mode of Action of Essential Oils. Evol. Bioinforma. Online Internet 2021, 17, 1176934320938391. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8114247/ (accessed on 7 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Shirley, N.; Bleackley, M.; Dolan, S.; Shafee, T. Transcriptomics technologies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, A. Factors affecting chemical variability of essential oils: A review of recent developments. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benomari, F.Z.; Sarazin, M.; Chaib, D.; Pichette, A.; Boumghar, H.; Boumghar, Y. Chemical Variability and Chemotype Concept of Essential Oils from Algerian Wild Plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudaib, M.; Speroni, E.; Pietra, A.M.; Cavrini, V. GC/MS evaluation of thyme [Thymus vulgaris L.] oil composition and variations during the vegetative cycle. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2002, 29, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshima, F.A.T.; Ming, L.C.; Marques, M.O.M. Produção de biomassa, rendimento de óleo essencial e de citral em capim-limão, Cymbopogon citratus [DC.] Stapf, com cobertura morta nas estações do ano. Rev. Bras. Plantas. Med. 2006, 8, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, T.C.; Freitas, S.D.P.; Silva, J.F.D.; Carvalho, A.C. Production of Biomass and Essential Oil in Plants of Lemongrass [Cymbopogon citratus [Dc] Stapf] of Various Ages. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Production-of-biomass-and-essential-oil-in-plants-Leal-Freitas/344f9408368e45bb2cfe5fc61913da2b62fec10b (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Padalia, R.C.; Verma, R.S.; Chauhan, A.; Tiwari, A.; Joshi, N. Variability in essential oil composition of different plant parts of Heracleum candicans Wall. Ex DC North India J. Essent. Oil Res. 2018, 30, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Benameur, Q.; Gervasi, T.; Pellizzeri, V.; Pľuchtová, M.; Tali-Maama, H.; Assaous, F.; Guettou, B.; Rahal, K.; Gruľová, D.; Dugo, G.; et al. Antibacterial activity of Thymus vulgaris essential oil alone and in combination with cefotaxime against bla ESBL producing multidrug resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, S.; Mukhia, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R. Essential oil composition and antimicrobial potential of aromatic plants grown in the mid-hill conditions of the Western Himalayas. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zidorn, C. Seasonal variations of natural products in European herbs. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1549–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharousi, Z.S.; Mothershaw, A.S.; Nzeako, B. Antimicrobial Activity of Frankincense [Boswellia sacra] Oil and Smoke against Pathogenic and Airborne Microbes. Foods 2023, 12, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, T.F.; Pereira, R.D.C.A.; Batista, V.C.V. Seasonal variability of the antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Lippia alba. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2014, 45, 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, D.P.; Poudel, D.K.; Satyal, P.; Khadayat, K.; Dhami, S.; Aryal, D.; Chaudhary, P.; Ghimire, A.; Parajuli, N. Volatile compounds and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of selected citrus essential oils originated from Nepal. Molecules 2021, 26, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, D.; El-Readi, M.Z.; Tahrani, A.; Herrmann, F.; Kaufmann, D.; Farrag, N.; El-Shazly, A.; Wink, M. Chemical composition and biological activity of Citrus jambhiri Lush. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciardi, M.C.; Blázquez, M.A.; Alberto, M.R.; Cartagena, E.; Arena, M.E. Grapefruit essential oils inhibit quorum sensing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2020, 26, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Motsa, N.M. Plant shoot age and temperature effects on essential oil yield and oil composition of rose-scented geranium (Pelargonium sp.) growth in South Africa. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalli, M.; Azizi, S.E.; Benouda, H.; Azghar, A.; Tahri, M.; Bouammali, B. Molecular Composition and Antibacterial Effect of Five Essential Oils Extracted from Nigella sativa L. Seeds against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: A Comparative Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6643765. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, J.P.; Barros, A.L.A.N.; Araújo-Nobre, A.R.; Sobrinho-Júnior, E.P.C.; Alves, M.M.D.M.; Carvalho, F.A.D.A.; Rodrigues, K.A.d.F.; de Andrade, I.M.; e Silva-Filho, F.A.; Moreira, D.C.; et al. Influence of plant age on chemical composition, antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of Varronia curassavica Jacq. essential oil produced on an industrial scale. Agriculture 2023, 13, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]