Attenuation of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms and Virulence by 3-Fluorocatechol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Antimicrobial Role of 3-FC Towards Pathogens

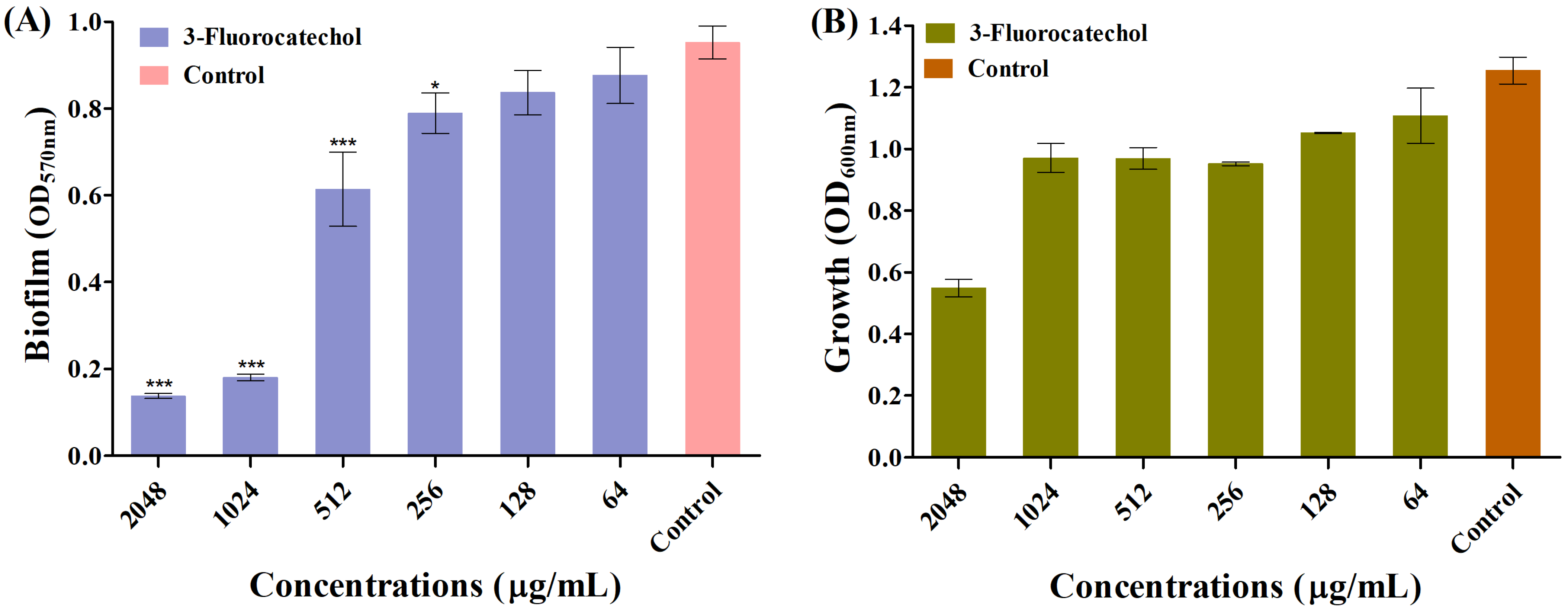

2.2. Biofilm Inhibitory Role of 3-FC

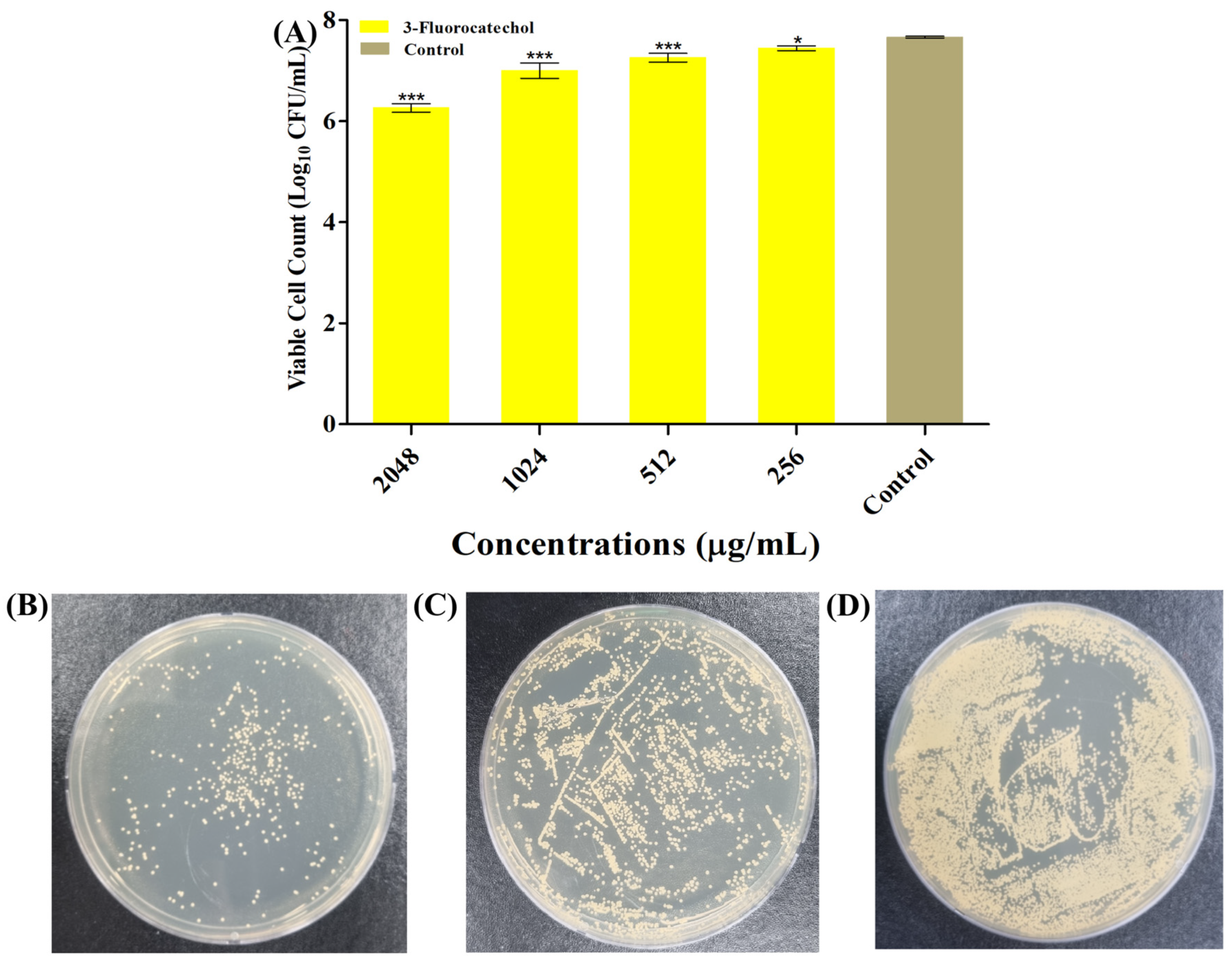

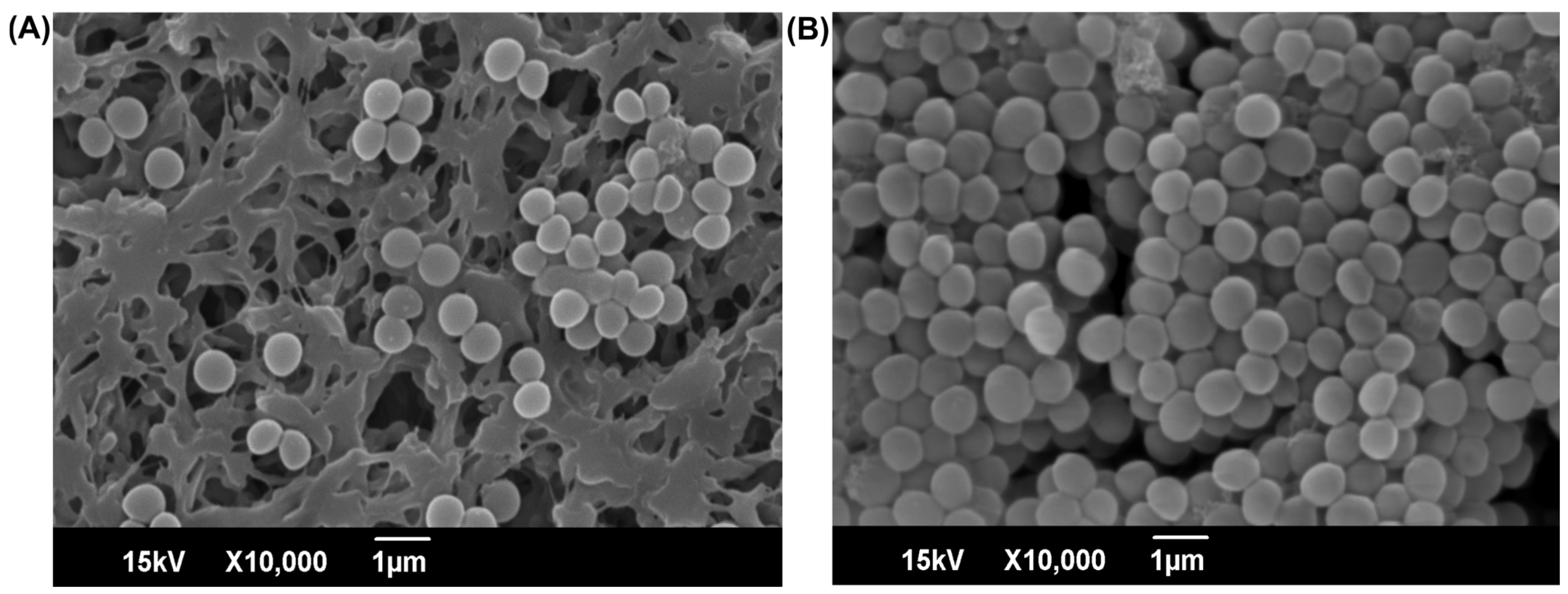

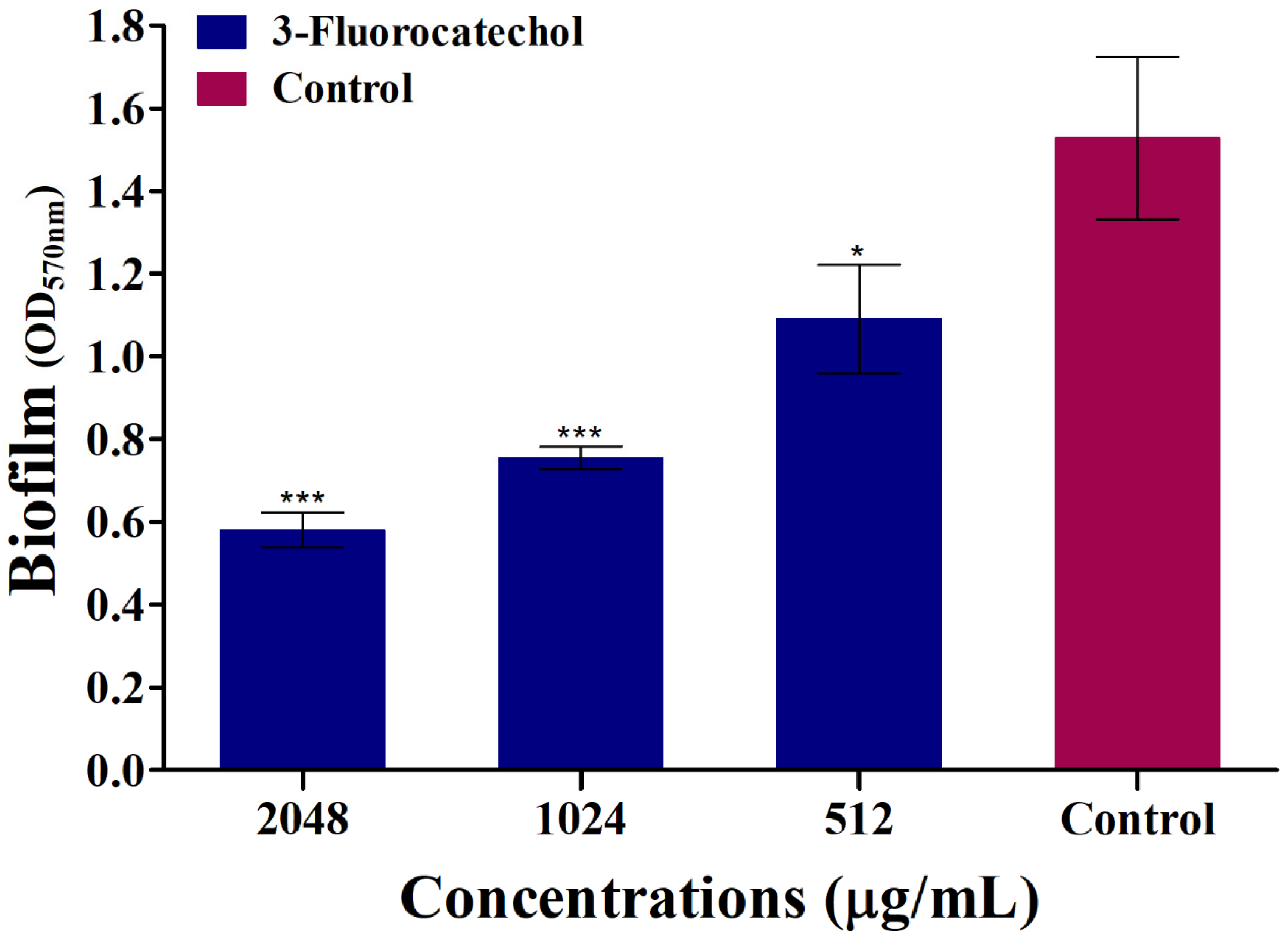

2.3. 3-FC Eradicates the Preformed Mature Biofilm of S. aureus

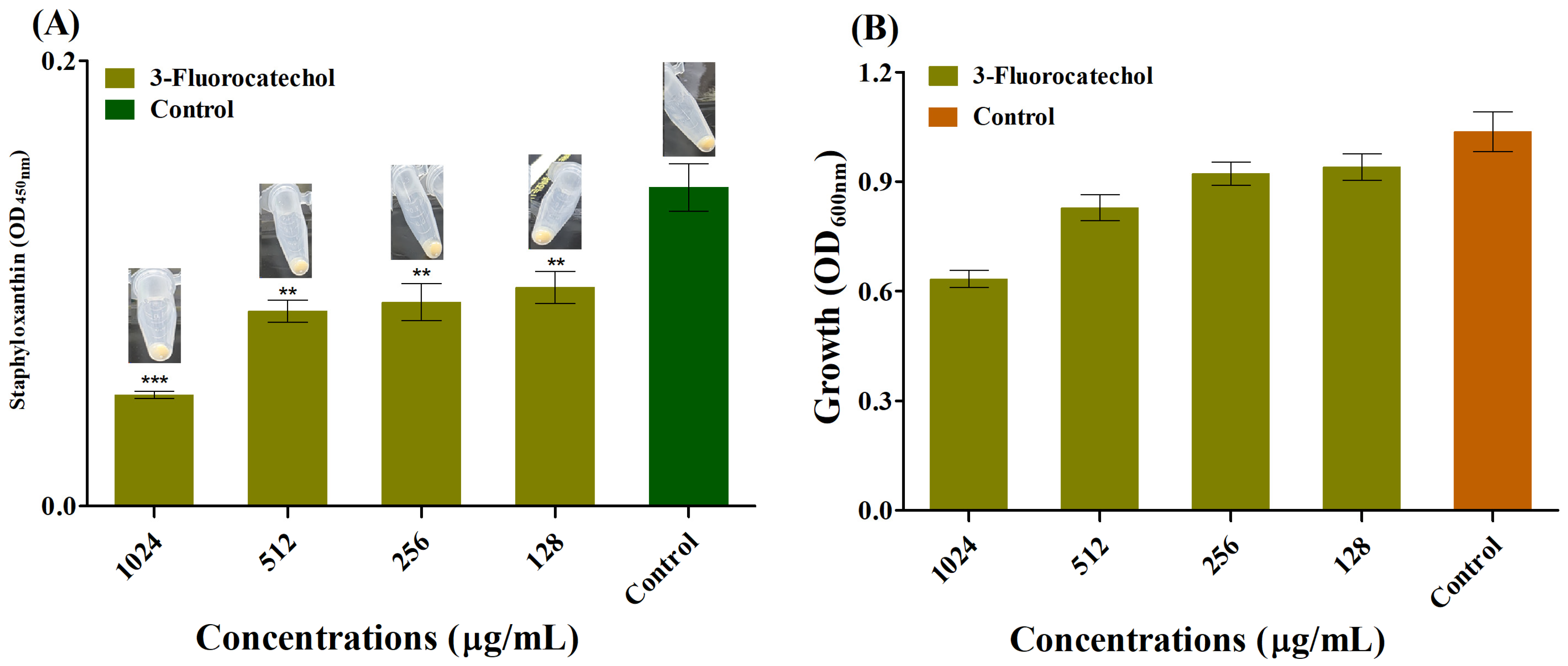

2.4. Anti-Staphyloxanthin Activity of 3-FC

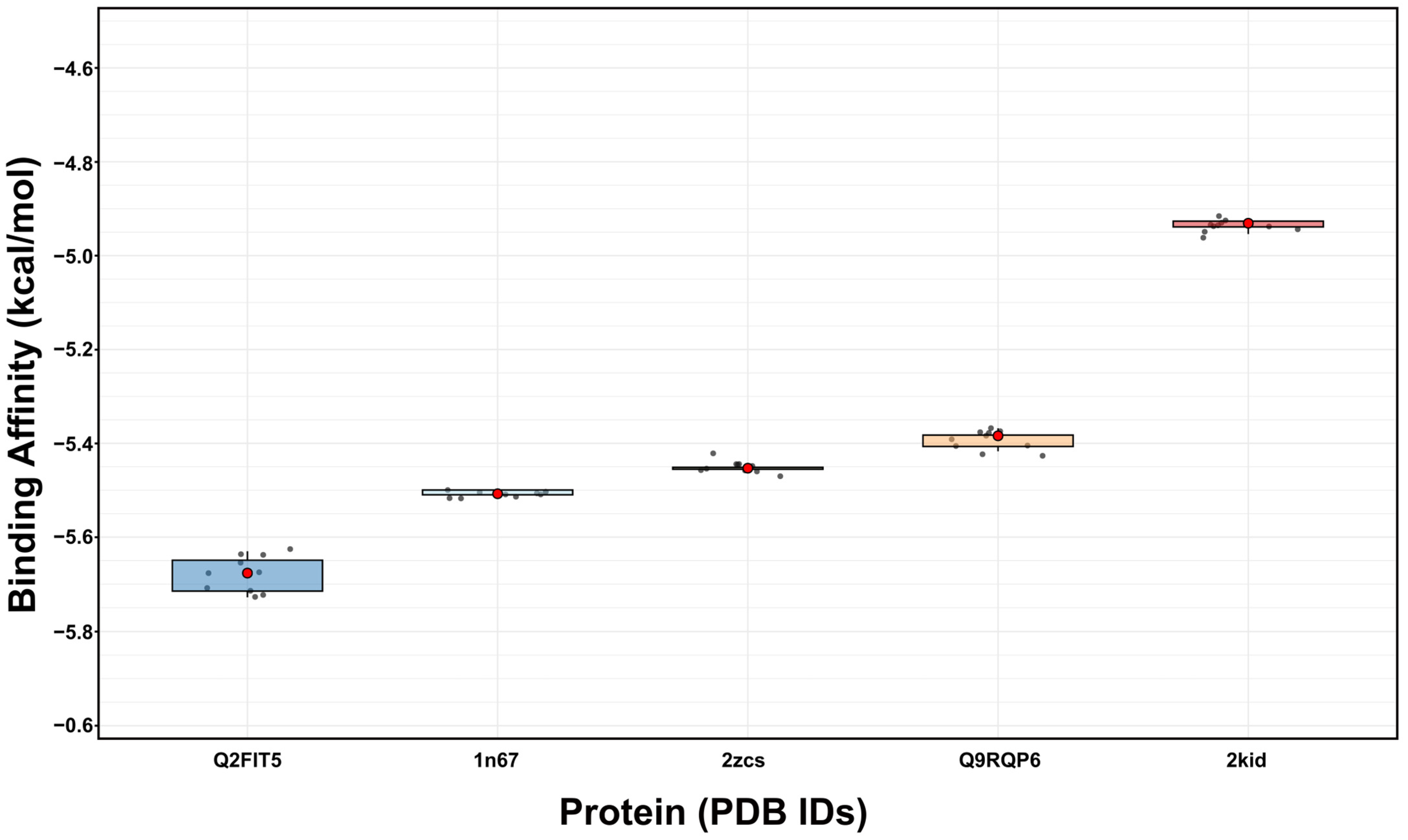

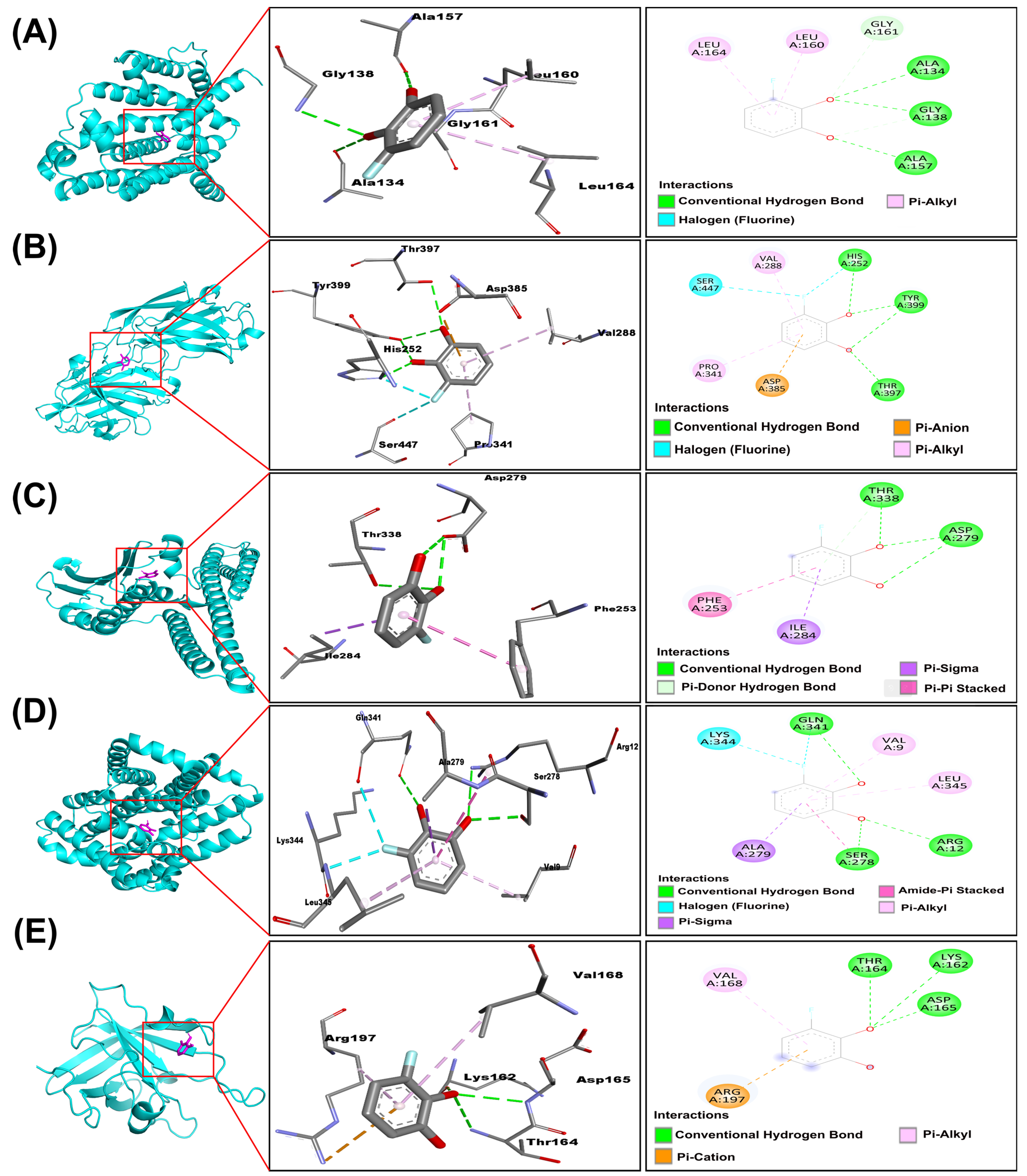

2.5. Molecular Interactions of 3-Fluorocatechol with Virulence Proteins of S. aureus

2.6. ADMET Analysis of 3-Fluorocatechol

3. Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents, Pathogens, Culture Media, and Instruments

4.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

4.3. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

4.4. Quantification of Viable Biofilm Cells (CFU Enumeration)

4.5. Eradication of Preformed Biofilm

4.6. Examination of Biofilm Cells Under SEM

4.7. Staphyloxanthin Assay

4.8. Selection and Preparation of S. aureus Virulence Factor

4.9. Preparation of 3-FC Ligand

4.10. Molecular Docking Analysis of 3-FC with Diverse Virulence Factors of S. aureus

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Touaitia, R.; Mairi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Basher, N.S.; Idres, T.; Touati, A. Staphylococcus aureus: A Review of the Pathogenesis and Virulence Mechanisms. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeo, F.R.; Chambers, H.F. Reemergence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomics era. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 2464–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdács, M. The Continuing Threat of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilcher, K.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcal Biofilm Development: Structure, Regulation, and Treatment Strategies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2020, 84, e00026-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrocola, G.; Campoccia, D.; Motta, C.; Montanaro, L.; Arciola, C.R.; Speziale, P. Colonization and Infection of Indwelling Medical Devices by Staphylococcus aureus with an Emphasis on Orthopedic Implants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, K.M.; Nguyen, J.M.; Berg, L.J.; Townsend, S.D. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Antibiotic-resistance and the biofilm phenotype. MedChemComm 2019, 10, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Santana, G.; Cabral-Oliveira, G.G.; Oliveira, D.R.; Nogueira, B.A.; Pereira-Ribeiro, P.M.A.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: An opportunistic pathogen with multidrug resistance. Rev. Res. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 32, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Sawant, S.; Karodia, N.; Rahman, A. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm: Morphology, Genetics, Pathogenesis and Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedarat, Z.; Taylor-Robinson, A.W. Biofilm Formation by Pathogenic Bacteria: Applying a Staphylococcus aureus Model to Appraise Potential Targets for Therapeutic Intervention. Pathogens 2022, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.N.; Morrisette, T.; Jorgensen, S.C.J.; Orench-Benvenutti, J.M.; Kebriaei, R. Current therapies and challenges for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-related infections. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2023, 43, 816–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Hu, Z.; Jin, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, C.; Qiang, R.; Xie, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, H. Structural characteristics, functions, and counteracting strategies of biofilms in Staphylococcus aureus. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T. Disarming Staphylococcus aureus: Review of Strategies Combating This Resilient Pathogen by Targeting Its Virulence. Pathogens 2025, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Xiong, J.; Yang, G.-X.; Hu, J.-F.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Z. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm: Formulation, regulatory, and emerging natural products-derived therapeutics. Biofilm 2024, 7, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Roland, J.D.; Lee, B.P. Antimicrobial property of halogenated catechols. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, K.C.; D’Angelo, I.; Kalscheuer, R.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.-X.; Snieckus, V.; Ly, L.H.; Converse, P.J.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Strynadka, N.; et al. Studies of a Ring-Cleaving Dioxygenase Illuminate the Role of Cholesterol Metabolism in the Pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, C.A.; Stratford, M.R.L.; Riley, P.A. The influence of catechol structure on the suicide-inactivation of tyrosinase. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3388–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraroni, M.; Kolomytseva, M.; Scozzafava, A.; Golovleva, L.; Briganti, F. X-ray structures of 4-chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase adducts with substituted catechols: New perspectives in the molecular basis of intradiol ring cleaving dioxygenases specificity. J. Struct. Biol. 2013, 181, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, P.D.; Mineyeva, Y.; Mycroft, Z.; Bugg, T.D.H. Chemical intervention in bacterial lignin degradation pathways: Development of selective inhibitors for intradiol and extradiol catechol dioxygenases. Bioorg. Chem. 2015, 60, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.M.; Shu, Y.-Z.; Zhuo, X.; Meanwell, N.A. Metabolic and Pharmaceutical Aspects of Fluorinated Compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 6315–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campana, R.; Mangiaterra, G.; Tiboni, M.; Frangipani, E.; Biavasco, F.; Lucarini, S.; Citterio, B. A Fluorinated Analogue of Marine Bisindole Alkaloid 2,2-Bis(6-bromo-1H-indol-3-yl)ethanamine as Potential Anti-Biofilm Agent and Antibiotic Adjuvant Against Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ahn, J.; Qiao, Z.; Endres, J.L.; Gautam, N.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Alnouti, Y.; et al. Novel fluorinated pyrrolomycins as potent anti-staphylococcal biofilm agents: Design, synthesis, pharmacokinetics and antibacterial activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 124, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmogy, S.; Ismail, M.A.; Hassan, R.Y.A.; Noureldeen, A.; Darwish, H.; Fayad, E.; Elsaid, F.; Elsayed, A. Biological Insights of Fluoroaryl-2,2′-Bichalcophene Compounds on Multi-Drug Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2021, 26, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Yin, M.; Yang, M.; Ren, J.; Liu, C.; Lian, J.; Lu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Luo, J. Lipase and pH-responsive diblock copolymers featuring fluorocarbon and carboxyl betaine for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. J. Control. Release 2024, 369, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, I.; Knackmuss, H.J.; Reineke, W. Suicide Inactivation of Catechol 2,3-Dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida mt-2 by 3-Halocatechols. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 47, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuta, A.; Ohnishi, K.; Harayama, S. Construction of chimeric catechol 2,3-dioxygenase exhibiting improved activity against the suicide inhibitor 4-methylcatechol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1804–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yestrepsky, B.D.; Sorenson, R.J.; Chen, M.; Larsen, S.D.; Sun, H. Novel Inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus Virulence Gene Expression and Biofilm Formation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-C.; Liu, F.; Zhu, K.; Shen, J.-Z. Natural Products That Target Virulence Factors in Antibiotic-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13195–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascioferro, S.; Carbone, D.; Parrino, B.; Pecoraro, C.; Giovannetti, E.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P. Therapeutic Strategies To Counteract Antibiotic Resistance in MRSA Biofilm-Associated Infections. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.Y.; Toh, Y.S. Anti-biofilm agents: Recent breakthrough against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pathog. Dis. 2014, 70, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.C.; Lee, H.K.; Wang, L.; Chaili, S.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Bayer, A.S.; Proctor, R.A.; Yeaman, M.R. Diflunisal and Analogue Pharmacophores Mediating Suppression of Virulence Phenotypes in Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, D.B.; Karukurichi, K.R.; de la Salud-Bea, R.; Nelson, D.L.; McCune, C.D. Use of fluorinated functionality in enzyme inhibitor development: Mechanistic and analytical advantages. J. Fluor. Chem. 2008, 129, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Muñoz, J.L.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Varon, R.; Garcia-Ruíz, P.A.; Tudela, J.; Garcia-Cánovas, F.; Rodríguez-López, J.N. Suicide inactivation of the diphenolase and monophenolase activities of tyrosinase. IUBMB Life 2010, 62, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, A.; Takakusa, H.; Kimura, T.; Inoue, S.-i.; Kusuhara, H.; Ando, O. Analysis of Mechanism-Based Inhibition of CYP 3A4 by a Series of Fluoroquinolone Antibacterial Agents. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1608–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaviamri, S.; Wang, K.; Liu, B.; Lee, B.P. Catechol-Based Antimicrobial Polymers. Molecules 2021, 26, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thebti, A.; Meddeb, A.; Ben Salem, I.; Bakary, C.; Ayari, S.; Rezgui, F.; Essafi-Benkhadir, K.; Boudabous, A.; Ouzari, H.-I. Antimicrobial Activities and Mode of Flavonoid Actions. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparella, A.S.; Lee, K.J.; Hayes, A.J.; Feng, J.; Feng, Z.; Cini, D.; Deshmukh, S.; Booker, G.W.; Wilce, M.C.J.; Polyak, S.W.; et al. Halogenation of Biotin Protein Ligase Inhibitors Improves Whole Cell Activity against Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajiboye, T.O.; Aliyu, M.; Isiaka, I.; Haliru, F.Z.; Ibitoye, O.B.; Uwazie, J.N.; Muritala, H.F.; Bello, S.A.; Yusuf, I.I.; Mohammed, A.O. Contribution of reactive oxygen species to (+)-catechin-mediated bacterial lethality. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016, 258, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazly Bazzaz, B.S.; Sarabandi, S.; Khameneh, B.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Effect of Catechins, Green tea Extract and Methylxanthines in Combination with Gentamicin Against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Combination therapy against resistant bacteria. J. Pharmacopunct. 2016, 19, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radji, M.; Agustama, R.A.; Elya, B.; Tjampakasari, C.R. Antimicrobial activity of green tea extract against isolates of methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus aureus and multi–drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulen, A.; Gasser, V.; Hoegy, F.; Perraud, Q.; Pesset, B.; Schalk, I.J.; Mislin, G.L.A. Synthesis and antibiotic activity of oxazolidinone–catechol conjugates against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 11567–11579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, T.O.; Habibu, R.S.; Saidu, K.; Haliru, F.Z.; Ajiboye, H.O.; Aliyu, N.O.; Ibitoye, O.B.; Uwazie, J.N.; Muritala, H.F.; Bello, S.A.; et al. Involvement of oxidative stress in protocatechuic acid-mediated bacterial lethality. MicrobiologyOpen 2017, 6, e00472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novás, M.; Matos, M.J. The Role of Trifluoromethyl and Trifluoromethoxy Groups in Medicinal Chemistry: Implications for Drug Design. Molecules 2025, 30, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiazza, C.; Billard, T.; Dickson, C.; Tlili, A.; Gampe, C.M. Chalcogen OCF3 Isosteres Modulate Drug Properties without Introducing Inherent Liabilities. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1586–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagu, S.B.; Yejella, R.P.; Bhandare, R.R.; Shaik, A.B. Design, Synthesis, and Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Novel Trifluoromethyl and Trifluoromethoxy Substituted Chalcone Derivatives. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldulaimi, O.A. General Overview of Phenolics from Plant to Laboratory, Good Antibacterials or Not. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2017, 11, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jothi, R.; Sangavi, R.; Kumar, P.; Pandian, S.K.; Gowrishankar, S. Catechol thwarts virulent dimorphism in Candida albicans and potentiates the antifungal efficacy of azoles and polyenes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Brivio, M.; Xiao, T.; Norwood, V.M.I.V.; Kim, Y.S.; Jin, S.; Papagni, A.; Vaghi, L.; Huigens, R.W., III. Modular Synthetic Routes to Fluorine-Containing Halogenated Phenazine and Acridine Agents That Induce Rapid Iron Starvation in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.A.A.; dos Santos Rodrigues, J.B.; Magnani, M.; de Souza, E.L.; de Siqueira-Júnior, J.P. Inhibitory effects of flavonoids on biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus that overexpresses efflux protein genes. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 107, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalari, G.; Minuti, A.; La Camera, E.; Barreca, D.; Romeo, O.; Nostro, A. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus Strains and Effect of Phloretin on Biofilm Formation. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastoor, S.; Nazim, F.; Rizwan-ul-Hasan, S.; Ahmed, K.; Khan, S.; Ali, S.N.; Abidi, S.H. Analysis of the Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Activity of Natural Compounds and Their Analogues against Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, A.T.; Bai, F.; Abouelhassan, Y.; Paciaroni, N.G.; Jin, S.; Huigens Iii, R.W. Bromophenazine derivatives with potent inhibition, dispersion and eradication activities against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, V.; Wahl, P.; Richards, R.G.; Moriarty, T.F. Vancomycin displays time-dependent eradication of mature Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Orthop. Res. 2017, 35, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihira, S.; Simpson, S.J.; Collier, C.D.; Natoli, R.M.; Kittaka, M.; Greenfield, E.M. Halicin Is Effective Against Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms In Vitro. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2022, 480, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Rao, L.; Zhan, L.; Wang, B.; Zhan, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. The small molecule ZY-214-4 may reduce the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus by inhibiting pigment production. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauditz, A.; Resch, A.; Wieland, K.-P.; Peschel, A.; Götz, F. Staphyloxanthin Plays a Role in the Fitness of Staphylococcus aureus and Its Ability To Cope with Oxidative Stress. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 4950–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.I.; Liu, G.Y.; Song, Y.; Yin, F.; Hensler, M.E.; Jeng, W.Y.; Nizet, V.; Wang, A.H.; Oldfield, E. A cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor blocks Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Science 2008, 319, 1391–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Liu, C.-I.; Lin, F.-Y.; No, J.H.; Hensler, M.; Liu, Y.-L.; Jeng, W.-Y.; Low, J.; Liu, G.Y.; Nizet, V.; et al. Inhibition of Staphyloxanthin Virulence Factor Biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus: In Vitro, in Vivo, and Crystallographic Results. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3869–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, K.; Hou, C.; Cai, S.; Huang, Y.; Du, Z.; Huang, H.; Kong, J.; Chen, Y. Baicalein Inhibits Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation and the Quorum Sensing System In Vitro. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.; Nelis, H.J.; Coenye, T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 72, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Oh, D.; Chandika, P.; Jo, D.-M.; Bamunarachchi, N.I.; Jung, W.-K.; Kim, Y.-M. Inhibitory activities of phloroglucinol-chitosan nanoparticles on mono- and dual-species biofilms of Candida albicans and bacteria. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 211, 112307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Park, S.-K.; Bamunuarachchi, N.I.; Oh, D.; Kim, Y.-M. Caffeine-loaded gold nanoparticles: Antibiofilm and anti-persister activities against pathogenic bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 3717–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-G.; Khan, F.; Tabassum, N.; Cho, K.-J.; Jo, D.-M.; Kim, Y.-M. Inhibition of Biofilm and Virulence Properties of Pathogenic Bacteria by Silver and Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized from Lactiplantibacillus sp. Strain C1. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 9873–9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Di, H.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Xu, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, N.; Liu, G.; Yang, C.-G.; Xu, Y.; et al. Small-molecule targeting of a diapophytoene desaturase inhibits S. aureus virulence. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.U.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O.; Guex, N. Defining and searching for structural motifs using DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deivanayagam, C.C.; Wann, E.R.; Chen, W.; Carson, M.; Rajashankar, K.R.; Höök, M.; Narayana, S.V. A novel variant of the immunoglobulin fold in surface adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus: Crystal structure of the fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM, clumping factor A. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 6660–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, C.; Kraft, A.; Süssmuth, R.; Schweitzer, O.; Götz, F. Characterization of the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity involved in the biosynthesis of the Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 18586–18593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, V.; Kumar, P.; Rakhaminov, G.; Qamar, A.; Fan, X.; Hunter, H.; Tomar, S.; Golemi-Kotra, D.; Kumar, P. Repurposing an Ancient Protein Core Structure: Structural Studies on FmtA, a Novel Esterase of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3107–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Strynadka, N.C. Structural basis for the beta lactam resistance of PBP2a from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002, 9, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, C.E.; Zurek, O.W.; Meishery, D.D.; Pallister, K.B.; Malone, C.L.; Horswill, A.R.; Voyich, J.M. Differential regulation of staphylococcal virulence by the sensor kinase SaeS in response to neutrophil-derived stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E2037–E2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yeo, W.S.; Bae, T. The SaeRS Two-Component System of Staphylococcus aureus. Genes 2016, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suree, N.; Liew, C.K.; Villareal, V.A.; Thieu, W.; Fadeev, E.A.; Clemens, J.J.; Jung, M.E.; Clubb, R.T. The structure of the Staphylococcus aureus sortase-substrate complex reveals how the universally conserved LPXTG sorting signal is recognized. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 24465–24477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminformatics 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strains | (MIC μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| S. mutans (KCCM 40105) | >2048 µg/mL |

| S. aureus (KCTC 1916) | >2048 µg/mL |

| E. coli (KCTC 1682) | >2048 µg/mL |

| L. monocytogenes (KCTC 3569) | >2048 µg/mL |

| K. pneumoniae (ATCC 4352) | >2048 µg/mL |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA; KCCM 40510) | >2048 µg/mL |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 (KCTC 1637) | 512 µg/mL |

| C. albicans (KCCM 11282) | 512 µg/mL |

| Target Proteins | 3-FC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein ID | Name | Mean Affinity ± 95%CI | Binding Residues | Interaction Types |

| 2zcs | Carotenoid dehydrosqualene synthase | −5.452 ± 0.007 | Ala 134, Gly 138, Ala 157, Leu 160, Gly 161, Leu 164 | Conventional hydrogen bond, Carbon–hydrogen bond, Pi-Alkyl |

| 1n67 | Clumping Factor A | −5.505 ± 0.005 | His 252, Val 288, Pro 341, Asp 385, Thr 397, Tyr 399, Ser 447 | Conventional hydrogen bond, Halogen, Pi-Anion, Pi-Alkyl |

| Q2FIT5 | Histidine protein kinase SaeS | −5.697 ± 0.027 | Phe 253, Asp 279, Ile 284, Thr 338 | Conventional hydrogen bond, Pi-Donor hydrogen bond, Pi-Sigma, Pi-Pi |

| Q9RQP6 | Poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine export protein | −5.392 ± 0.013 | Val 9, Arg 12, Ser 278, Ala 279, Gln 341, Lys 344, Leu 345 | Conventional hydrogen bond, Amide-Pi, Halogen, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Sigma |

| 2kid | Sortase A | −4.933 ± 0.008 | Lys 162, Thr 162, Asp 165, Val 168, Arg 197 | Conventional hydrogen bond, Pi-Alkyl, Pi-Cation |

| Protein | PDB and Uniport ID | Functional Roles | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrtM | 2zcs | Staphyloxanthin synthesis | [56] |

| ClfA | 1n67 | Facilitates bacterial adhesion to fibrinogen and endothelial cells. | [68] |

| IcaD FmtA | Q9RQP6 | Stabilizes IcaA activity and promotes PIA synthesis. | [69,70,71,72] |

| SaeS | AF-Q2FIT5-F1 | Part of the SaeRS two-component system regulating immune evasion and biofilm genes. | [73] |

| Sortase A | 2kid | Anchors surface proteins to peptidoglycan, promoting colonization and biofilm formation. | [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, T.; Tabassum, N.; Javaid, A.; Khan, F. Attenuation of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms and Virulence by 3-Fluorocatechol. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121240

Kim T, Tabassum N, Javaid A, Khan F. Attenuation of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms and Virulence by 3-Fluorocatechol. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121240

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Taehyeong, Nazia Tabassum, Aqib Javaid, and Fazlurrahman Khan. 2025. "Attenuation of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms and Virulence by 3-Fluorocatechol" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121240

APA StyleKim, T., Tabassum, N., Javaid, A., & Khan, F. (2025). Attenuation of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms and Virulence by 3-Fluorocatechol. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121240