Genomic Characterization of NDM-1 Producer Providencia stuartii Isolated in Russia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Case Overview

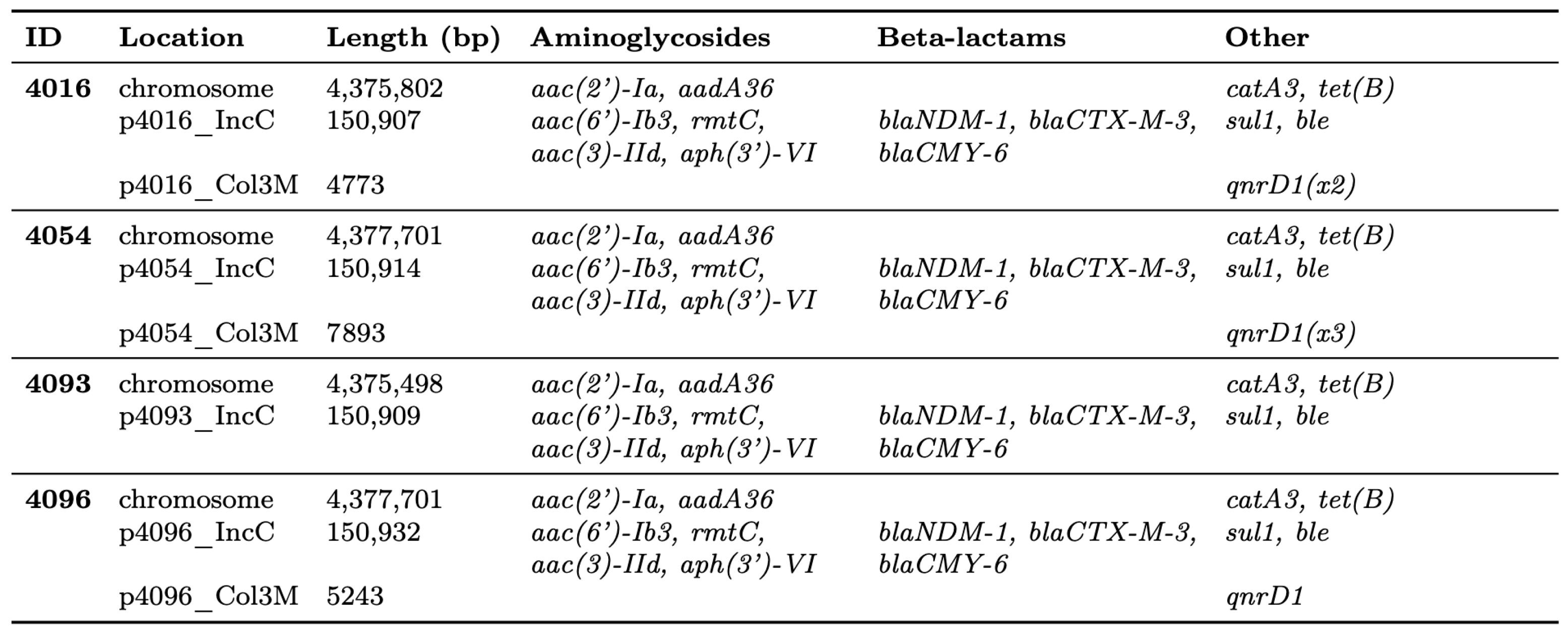

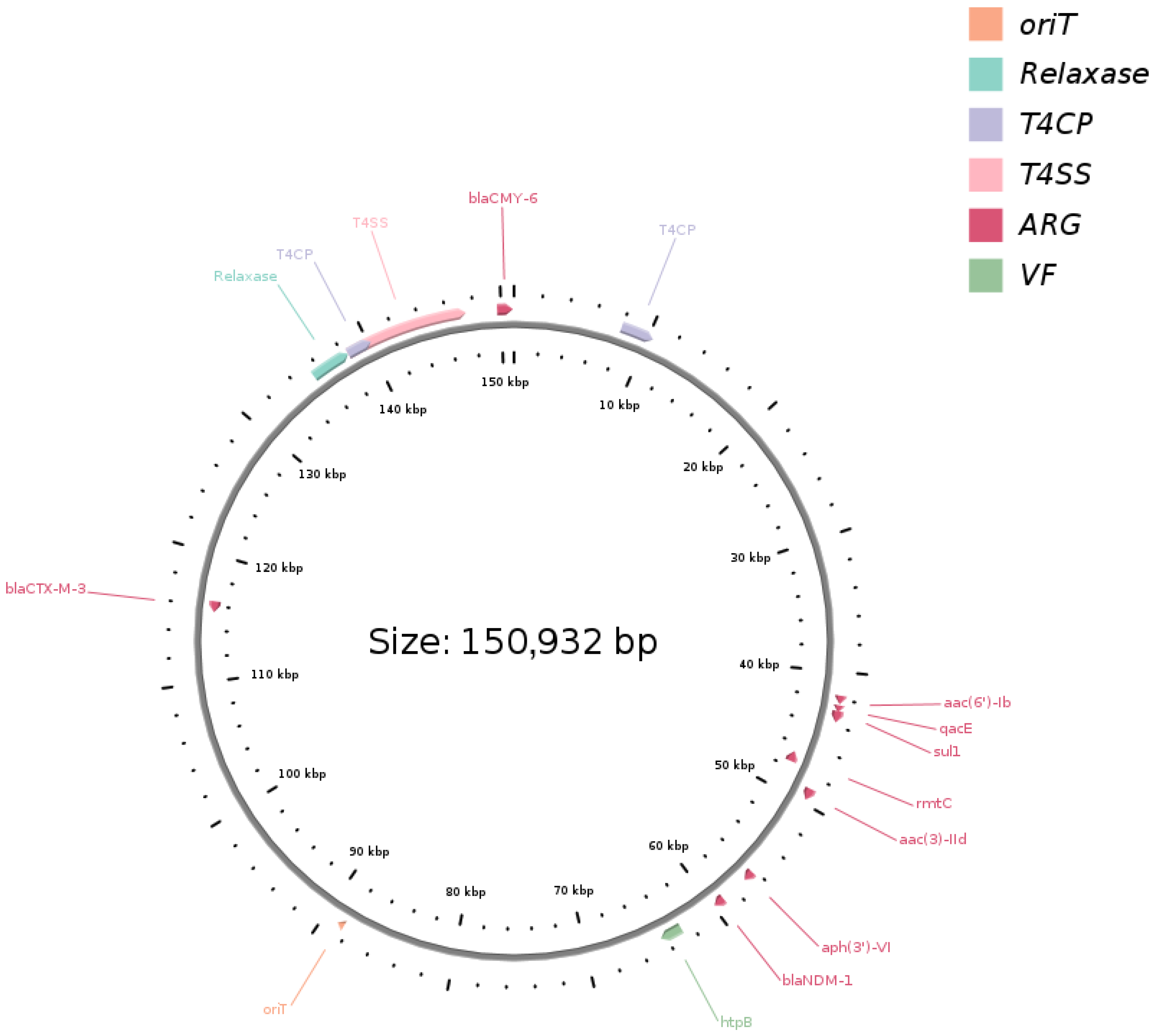

2.2. Genome Features, IncC Plasmid Variation, and Resistome Profiling

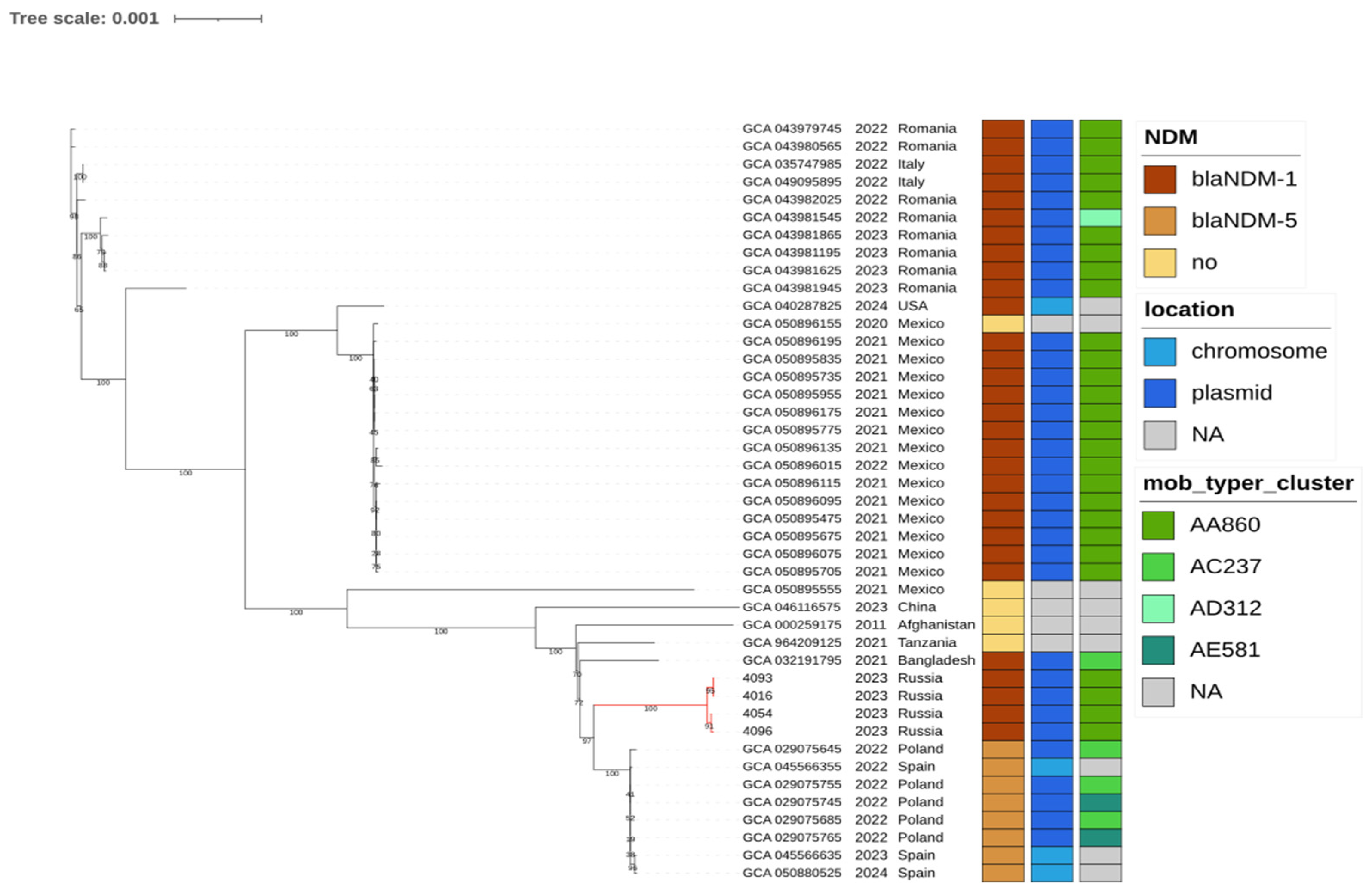

2.3. Global Phylogenetic Context

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.2. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

4.3. Genome Assembly and Genotyping

4.4. Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Analysis

4.5. Data Availability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Hara, C.M.; Brenner, F.W.; Miller, J.M. Classification, Identification, and Clinical Significance of Proteus, Providencia, and Morganella. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteveen, S.; Hendrickx, A.P.A. Providencia stuartii. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 810–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acman, M.; Wang, R.; Van Dorp, L.; Shaw, L.P.; Wang, Q.; Luhmann, N.; Yin, Y.; Sun, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Role of Mobile Genetic Elements in the Global Dissemination of the Carbapenem Resistance Gene blaNDM. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alglave, L.; Faure, K.; Mullié, C. Plasmid Dissemination in Multispecies Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales Outbreaks Involving Clinical and Environmental Strains: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Chen, R.; Li, C.; Sun, J.; Liu, R.; Shen, Y.; Guo, X. The Association between the Genetic Structures of Commonly Incompatible Plasmids in Gram-Negative Bacteria, Their Distribution and the Resistance Genes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1472876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dagan, T. The Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance Islands Occurs within the Framework of Plasmid Lineages. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Jia, H.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Genomic Revisitation and Reclassification of the Genus Providencia. mSphere 2024, 9, e00731-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrook, M.; Muyldermans, A.; Sahm, D.; Pierard, D.; Stone, G.; Utt, E. Epidemiology of Resistance Determinants Identified in Meropenem-Nonsusceptible Enterobacterales Collected as Part of a Global Surveillance Study, 2018 to 2019. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e01406-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidone, G.H.M.; Cardozo, J.G.; Silva, L.C.; Sanches, M.S.; Galhardi, L.C.F.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Vespero, E.C.; Rocha, S.P.D. Epidemiology and Characterization of Providencia stuartii Isolated from Hospitalized Patients in Southern Brazil: A Possible Emerging Pathogen. Access Microbiol. 2023, 5, 000652.v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolberg, R.S.; Hansen, F.; Porsbo, L.J.; Karstensen, K.T.; Roer, L.; Holzknecht, B.J.; Hansen, K.H.; Schønning, K.; Wang, M.; Justesen, U.S.; et al. Genotypic Characterisation of Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms Obtained in Denmark from Patients Associated with the War in Ukraine. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 34, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwittink, R.D.; Wielders, C.C.; Notermans, D.W.; Verkaik, N.J.; Schoffelen, A.F.; Witteveen, S.; Ganesh, V.A.; De Haan, A.; Bos, J.; Bakker, J.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Patients from Ukraine in the Netherlands, March to August 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2200896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzoug, I.; Emeraud, C.; Girlich, D.; Creton, E.; Naas, T.; Bonnin, R.A.; Dortet, L. Characterization of VIM-29 and VIM-86, Two VIM-1 Variants Isolated in Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales in France. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 683–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitani, V.; Arcari, G.; Oliva, A.; Sacco, F.; Menichincheri, G.; Fenske, L.; Polani, R.; Raponi, G.; Antonelli, G.; Carattoli, A. Genome-Based Retrospective Analysis of a Providencia stuartii Outbreak in Rome, Italy: Broad Spectrum IncC Plasmids Spread the NDM Carbapenemase within the Hospital. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabtcheva, S.; Stoikov, I.; Ivanov, I.N.; Donchev, D.; Lesseva, M.; Georgieva, S.; Teneva, D.; Dobreva, E.; Christova, I. Genomic Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacter hormaechei, Serratia marcescens, Citrobacter freundii, Providencia stuartii, and Morganella morganii Clinical Isolates from Bulgaria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkevicius, M.; Witteveen, S.; Buzea, M.; Flonta, M.; Indreas, M.; Nica, M.; Székely, E.; Tălăpan, D.; Svartström, O.; Alm, E.; et al. Genomic Surveillance Detects Interregional Spread of New Delhi Metallo-Beta-Lactamase-1-Producing Providencia stuartii in Hospitals, Romania, December 2021 to September 2023. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteveen, S.; Hans, J.B.; Izdebski, R.; Hasman, H.; Samuelsen, Ø.; Dortet, L.; Pfeifer, Y.; Delappe, N.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Żabicka, D.; et al. Dissemination of Extensively Drug-Resistant NDM-Producing Providencia stuartii in Europe Linked to Patients Transferred from Ukraine, March 2022 to March 2023. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2300616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid Investigation of New Delhi Metallo-Beta-Lactamase (NDM)-1-Producing Providencia stuartii in Hospitals in Romania: November 2024; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe, 2024 Data: Executive Summary; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Winans, S.C. TraA, TraC and TraD Autorepress Two Divergent Quorum-regulated Promoters near the Transfer Origin of the Ti Plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 63, 1769–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macesic, N.; Hawkey, J.; Vezina, B.; Wisniewski, J.A.; Cottingham, H.; Blakeway, L.V.; Harshegyi, T.; Pragastis, K.; Badoordeen, G.Z.; Dennison, A.; et al. Genomic Dissection of Endemic Carbapenem Resistance Reveals Metallo-Beta-Lactamase Dissemination through Clonal, Plasmid and Integron Transfer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalova, V.V.; Chulkova, P.S.; Ageevets, V.A.; Nurmukanova, V.; Verentsova, I.V.; Girina, A.A.; Protasova, I.N.; Bezbido, V.S.; Sergevnin, V.I.; Feldblum, I.V.; et al. High-Risk Lineages of Hybrid Plasmids Carrying Virulence and Carbapenemase Genes. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zee, A.; Roorda, L.; Bosman, G.; Fluit, A.C.; Hermans, M.; Smits, P.H.; Van Der Zanden, A.G.; Te Witt, R.; Bruijnesteijn Van Coppenraet, L.E.; Cohen Stuart, J.; et al. Multi-Centre Evaluation of Real-Time Multiplex PCR for Detection of Carbapenemase Genes OXA-48, VIM, IMP, NDM and KPC. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalova, V.; Shaidullina, E.; Azizov, I.; Sheck, E.; Martinovich, A.; Dyachkova, M.; Matsvay, A.; Savochkina, Y.; Khafizov, K.; Kozlov, R.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Mcr-1-Positive Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates: Results from Russian Sentinel Surveillance (2013–2018). Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado. Available online: https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Babraham Bioinformatics—FastQC A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Lanfear, R.; Schalamun, M.; Kainer, D.; Wang, W.; Schwessinger, B. MinIONQC: Fast and Simple Quality Control for MinION Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, R.A., III. Dragonflye: Assemble Bacterial Isolate Genomes from Nanopore Reads. Available online: https://github.com/rpetit3/dragonflye/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the Quality of Microbial Genomes Recovered from Isolates, Single Cells, and Metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: A Database Tandem for Fast and Reliable Genome-Based Classification and Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Frye, J.G.; Haendiges, J.; Haft, D.H.; Hoffmann, M.; Pettengill, J.B.; Prasad, A.B.; Tillman, G.E.; et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog Facilitate Examination of the Genomic Links among Antimicrobial Resistance, Stress Response, and Virulence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-Suite: Software Tools for Clustering, Reconstruction and Typing of Plasmids from Draft Assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, M.; Tai, C.; Sun, J.; Deng, Z.; Ou, H.-Y. oriTfinder: A Web-Based Tool for the Identification of Origin of Transfers in DNA Sequences of Bacterial Mobile Genetic Elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W229–W234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treangen, T.J.; Ondov, B.D.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. The Harvest Suite for Rapid Core-Genome Alignment and Visualization of Thousands of Intraspecific Microbial Genomes. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonkin-Hill, G.; Lees, J.A.; Bentley, S.D.; Frost, S.D.W.; Corander, J. Fast Hierarchical Bayesian Analysis of Population Structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5539–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin-Hill, G.; MacAlasdair, N.; Ruis, C.; Weimann, A.; Horesh, G.; Lees, J.A.; Gladstone, R.A.; Lo, S.; Beaudoin, C.; Floto, R.A.; et al. Producing Polished Prokaryotic Pangenomes with the Panaroo Pipeline. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Taylor, B.; Delaney, A.J.; Soares, J.; Seemann, T.; Keane, J.A.; Harris, S.R. SNP-Sites: Rapid Efficient Extraction of SNPs from Multi-FASTA Alignments. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argimón, S.; Abudahab, K.; Goater, R.J.E.; Fedosejev, A.; Bhai, J.; Glasner, C.; Feil, E.J.; Holden, M.T.G.; Yeats, C.A.; Grundmann, H.; et al. Microreact: Visualizing and Sharing Data for Genomic Epidemiology and Phylogeography. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, C.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Phillippy, A.M.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Aluru, S. High Throughput ANI Analysis of 90K Prokaryotic Genomes Reveals Clear Species Boundaries. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Mai, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Dai, L.; Deng, Z.; Ma, Y. Global Transmission of Broad-Host-Range Plasmids Derived from the Human Gut Microbiome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 8005–8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.C.; Jian, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Pei, N. One Health Analysis of Mcr -Carrying Plasmids and Emergence of Mcr-10.1 in Three Species of Klebsiella Recovered from Humans in China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02306-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolova, D.; Lima, L.; Roberts, L.W.; Bohnenkämper, L.; Wittler, R.; Stoye, J.; Iqbal, Z. Applying Rearrangement Distances to Enable Plasmid Epidemiology with Pling. Microb. Genom. 2024, 10, 001300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Bessonov, K.; Schonfeld, J.; Nash, J.H.E. Universal Whole-Sequence-Based Plasmid Typing and Its Utility to Prediction of Host Range and Epidemiological Surveillance. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, e000435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Age | Sex | Admit Date | Admitting Diagnosis | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4016 | 56 | F | 13 June 2023 | Umbilical hernia with obstruction, without gangrene | Central venous catheter |

| 4054 | 82 | F | 19 June 2023 | Malignant neoplasm, unspecified site | Wound |

| 4093 | 33 | M | 4 July 2023 | Cutaneous abscess, furuncle and carbuncle of limb | Wound |

| 4096 | 64 | F | 27 July 2023 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage from middle cerebral artery | Wound |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shapovalova, V.V.; Ageevets, V.A.; Ageevets, I.V.; Avdeeva, A.A.; Sulian, O.S.; Matsvay, A.D.; Savochkina, Y.A.; Belyakova, E.N.; Shipulin, G.A.; Sidorenko, S.V. Genomic Characterization of NDM-1 Producer Providencia stuartii Isolated in Russia. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121238

Shapovalova VV, Ageevets VA, Ageevets IV, Avdeeva AA, Sulian OS, Matsvay AD, Savochkina YA, Belyakova EN, Shipulin GA, Sidorenko SV. Genomic Characterization of NDM-1 Producer Providencia stuartii Isolated in Russia. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121238

Chicago/Turabian StyleShapovalova, Valeria V., Vladimir A. Ageevets, Irina V. Ageevets, Alisa A. Avdeeva, Ofeliia S. Sulian, Alina D. Matsvay, Yuliya A. Savochkina, Ekaterina N. Belyakova, German A. Shipulin, and Sergey V. Sidorenko. 2025. "Genomic Characterization of NDM-1 Producer Providencia stuartii Isolated in Russia" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121238

APA StyleShapovalova, V. V., Ageevets, V. A., Ageevets, I. V., Avdeeva, A. A., Sulian, O. S., Matsvay, A. D., Savochkina, Y. A., Belyakova, E. N., Shipulin, G. A., & Sidorenko, S. V. (2025). Genomic Characterization of NDM-1 Producer Providencia stuartii Isolated in Russia. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121238