Serovar-Dependent Gene Regulation and Antimicrobial Tolerance in Streptococcus suis Biofilms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Gene Expression Analysis in a Selection of Streptococcus suis Isolates

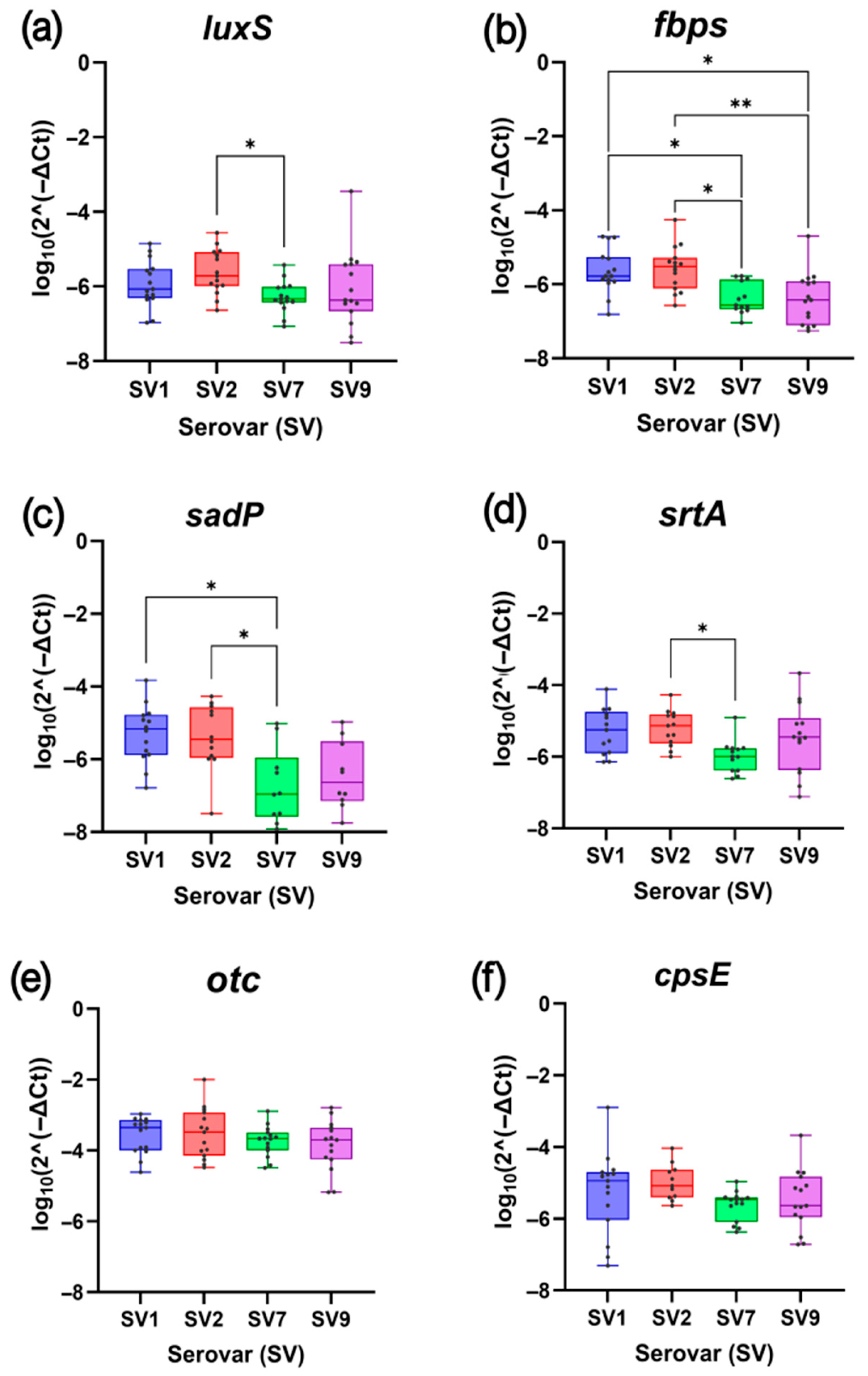

2.1.1. Comparative Analysis of Biofilm-Related Gene Expression

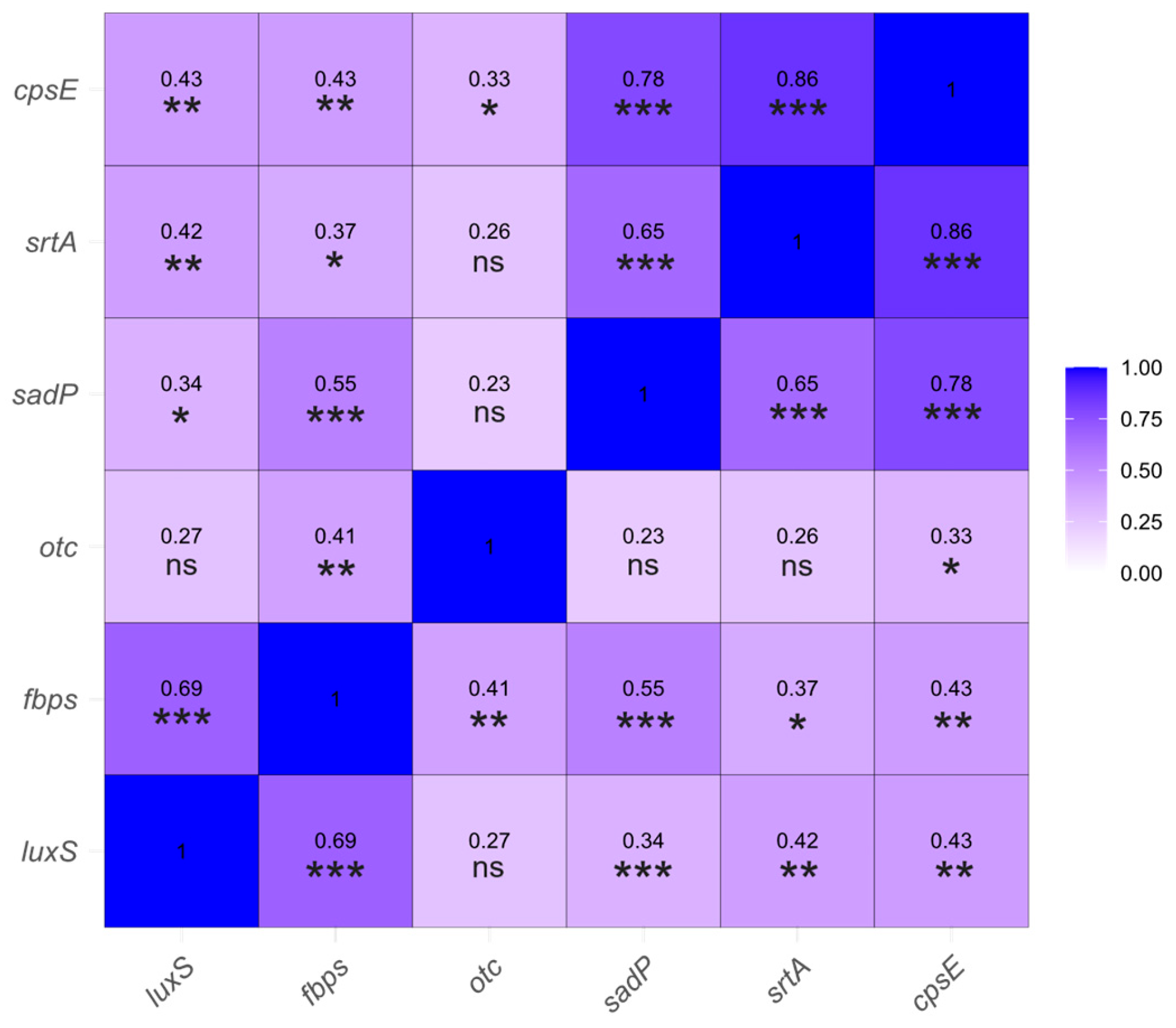

2.1.2. Correlation Analysis of Gene Expression Levels

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Assays and Biofilm Characterization in Streptococcus suis

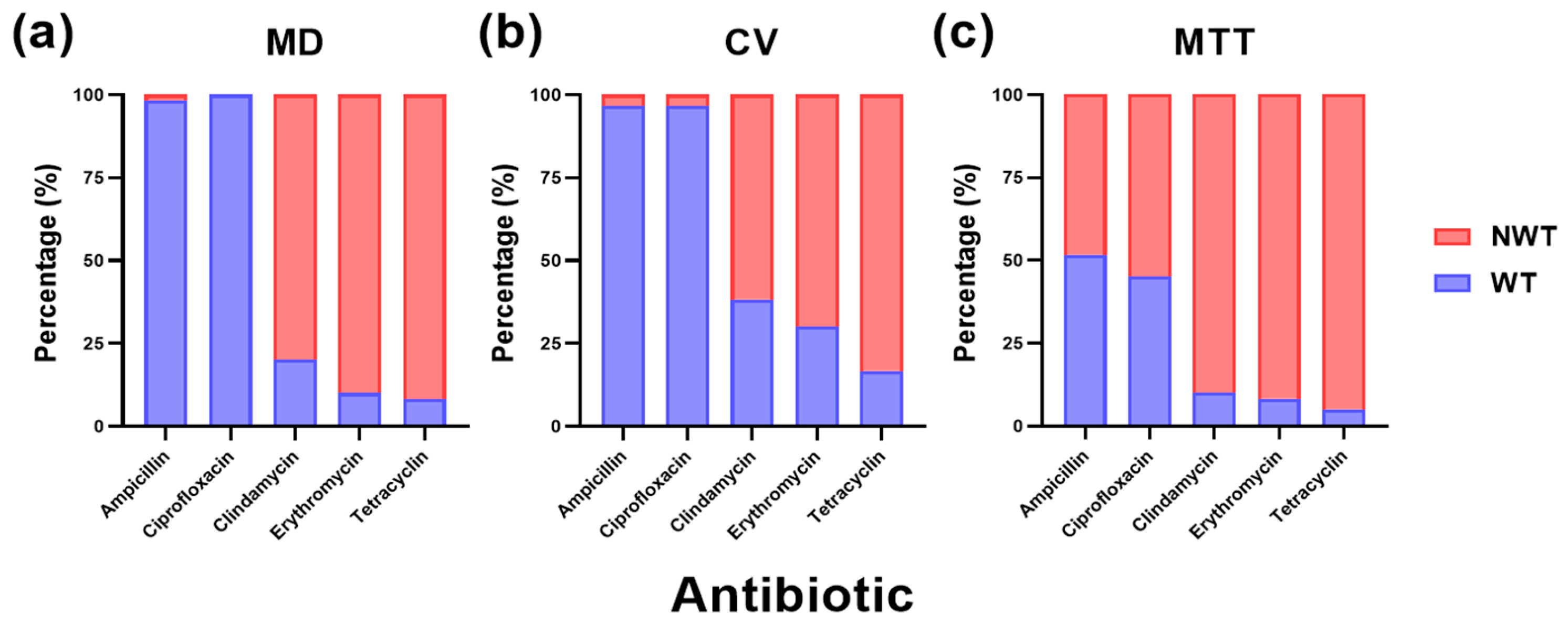

2.2.1. Impact of Biofilm Lifestyle on the Wild-Type and Non-Wild-Type Phenotypes of Streptococcus suis Against Commonly Used Antibiotics

2.2.2. Impact of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Methods on the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

2.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Serovar-Specific Antimicrobial Susceptibility

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Selection of Streptococcus suis Isolates

4.2. Gene Expression Analysis by RT-qPCR

4.2.1. Biofilm Formation

4.2.2. RNA Extraction

4.2.3. Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Assays and Biofilm Characterization

4.3.1. Preparation of Antibiotic Solutions

4.3.2. Inoculum Preparation and Inoculation Using the Broth Microdilution Method

4.3.3. Biofilm Biomass Quantification Using the Crystal Violet Assay

4.3.4. Cell Viability Assessment Using the MTT Assay

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goyette-Desjardins, G.; Auger, J.-P.; Xu, J.; Segura, M.; Gottschalk, M. Streptococcus suis, an Important Pig Pathogen and Emerging Zoonotic Agent—An Update on the Worldwide Distribution Based on Serotyping and Sequence Typing. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2014, 3, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vötsch, D.; Willenborg, M.; Weldearegay, Y.B.; Valentin-Weigand, P. Streptococcus suis—The “Two Faces” of a Pathobiont in the Porcine Respiratory Tract. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, M.L.; Schultsz, C. A Hypothetical Model of Host-Pathogen Interaction of Streptococcus suis in the Gastro-Intestinal Tract. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, M.; Calzas, C.; Grenier, D.; Gottschalk, M. Initial Steps of the Pathogenesis of the Infection Caused by Streptococcus suis: Fighting against Nonspecific Defenses. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 3772–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Samkar, A.; Brouwer, M.C.; Schultsz, C.; van der Ende, A.; van de Beek, D. Streptococcus suis Meningitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0004191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, S.; Cao, M.; Hu, D.; Wang, C. Streptococcus suis Infection. Virulence 2014, 5, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okura, M.; Osaki, M.; Nomoto, R.; Arai, S.; Osawa, R.; Sekizaki, T.; Takamatsu, D. Current Taxonomical Situation of Streptococcus suis. Pathogens 2016, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Lacouture, S.; Lewandowski, E.; Thibault, E.; Gantelet, H.; Gottschalk, M.; Fittipaldi, N. Molecular Characterization of Streptococcus suis Isolates Recovered from Diseased Pigs in Europe. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocchi Rilo, M.; Gutiérrez Martín, C.B.; Acebes Fernández, V.; Aguarón Turrientes, Á.; González Fernández, A.; Miguélez Pérez, R.; Martínez Martínez, S. Streptococcus suis Research Update: Serotype Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance Distribution in Swine Isolates Recovered in Spain from 2020 to 2022. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, J.-P.; Fittipaldi, N.; Benoit-Biancamano, M.-O.; Segura, M.; Gottschalk, M. Virulence Studies of Different Sequence Types and Geographical Origins of Streptococcus suis Serotype 2 in a Mouse Model of Infection. Pathogens 2016, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradanas, M.; Poljak, Z.; Fittipaldi, N.; Ricker, N.; Farzan, A. Serotypes, Virulence-Associated Factors, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Streptococcus suis Isolates Recovered From Sick and Healthy Pigs Determined by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 742345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodsant, T.J.; Van Der Putten, B.C.L.; Tamminga, S.M.; Schultsz, C.; Van Der Ark, K.C.H. Identification of Streptococcus suis Putative Zoonotic Virulence Factors: A Systematic Review and Genomic Meta-Analysis. Virulence 2021, 12, 2787–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, A.A.; Gottschalk, M.; Rendahl, A.; Rossow, S.; Marshall-Lund, L.; Marthaler, D.G.; Gebhart, C.J. Proposed Virulence-Associated Genes of Streptococcus suis Isolates from the United States Serve as Predictors of Pathogenicity. Porc. Health Manag. 2021, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura, M.; Fittipaldi, N.; Calzas, C.; Gottschalk, M. Critical Streptococcus suis Virulence Factors: Are They All Really Critical? Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okura, M.; Takamatsu, D.; Maruyama, F.; Nozawa, T.; Nakagawa, I.; Osaki, M.; Sekizaki, T.; Gottschalk, M.; Kumagai, Y.; Hamada, S. Genetic Analysis of Capsular Polysaccharide Synthesis Gene Clusters from All Serotypes of Streptococcus suis: Potential Mechanisms for Generation of Capsular Variation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2796–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Grenier, D.; Yi, L. Streptococcus suis Biofilm: Regulation, Drug-Resistance Mechanisms, and Disinfection Strategies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9121–9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An Emergent Form of Bacterial Life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Grenier, D.; Yi, L. The LuxS/AI-2 System of Streptococcus suis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7231–7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyoki, A.M.; Shi, Z.; Xuan, C.; Lu, G.; Qi, J.; Gao, F.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Haywood, J.; et al. Structural and Functional Analysis of an Anchorless Fibronectin-Binding Protein FBPS from Gram-Positive Bacterium Streptococcus suis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13869–13874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, A.; Haataja, S.; Loimaranta, V.; Pulliainen, A.T.; Nilsson, U.J.; Finne, J. Identification of a Novel Streptococcal Adhesin P (SadP) Protein Recognizing Galactosyl-A1–4-Galactose-Containing Glycoconjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 38854–38864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ying, L.; Shi, Y.; Dong, Y.; Fu, M.; Shen, Z. Potential Mechanisms of Streptococcus suis Virulence-Related Factors in Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption. One Health Adv. 2024, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yi, L.; Wang, Y. Rethinking the Control of Streptococcus suis Infection: Biofilm Formation. Vet. Microbiol. 2024, 290, 110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgano, M.; Pellegrini, F.; Catalano, E.; Capozzi, L.; Del Sambro, L.; Sposato, A.; Lucente, M.S.; Vasinioti, V.I.; Catella, C.; Odigie, A.E.; et al. Acquired Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics and Resistance Genes: From Past to Future. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruén, C.; Chopo-Escuin, G.; Tommassen, J.; Mainar-Jaime, R.C.; Arenas, J. Biofilms as Promoters of Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance and Tolerance. Antibiotics 2020, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Bassler, B.L. Surviving as a Community: Antibiotic Tolerance and Persistence in Bacterial Biofilms. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Jin, M.; Li, J.; Grenier, D.; Wang, Y. Antibiotic Resistance Related to Biofilm Formation in Streptococcus suis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8649–8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Gong, S.; Dong, X.; Mao, C.; Yi, L. LuxS/AI-2 System Is Involved in Fluoroquinolones Susceptibility in Streptococcus suis through Overexpression of Efflux Pump SatAB. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 233, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguélez-Pérez, R.; Mencía-Ares, O.; Gutiérrez-Martín, C.B.; González-Fernández, A.; Petrocchi-Rilo, M.; Delgado-García, M.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Biofilm Formation in Streptococcus suis: In Vitro Impact of Serovars and Assessment of Coinfections with Other Porcine Respiratory Disease Complex Bacterial Pathogens. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Mao, C.; Yuan, S.; Quan, Y.; Jin, W.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yi, L.; Wang, Y. AI-2 Quorum Sensing-Induced Galactose Metabolism Activation in Streptococcus suis Enhances Capsular Polysaccharide-Associated Virulence. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, H.; Cheng, X.; Lu, C. Overexpression of LuxS Cannot Increase Autoinducer-2 Production, Only Affect the Growth and Biofilm Formation in Streptococcus suis. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 924276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, H.; Cheng, X.; Lu, C. Biofilm Formation, Host-Cell Adherence, and Virulence Genes Regulation of Streptococcus suis in Response to Autoinducer-2 Signaling. Curr. Microbiol. 2014, 68, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Fan, Q.; Wang, H.; Fan, H.; Zuo, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Establishment of Streptococcus suis Biofilm Infection Model In Vivo and Comparative Analysis of Gene Expression Profiles between In Vivo and In Vitro Biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0268622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruén, C.; García, C.; Fraile, L.; Tommassen, J.; Arenas, J. How Streptococcus suis Escapes Antibiotic Treatments. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Stoodley, L.; Nistico, L.; Sambanthamoorthy, K.; Dice, B.; Nguyen, D.; Mershon, W.J.; Johnson, C.; Hu, F.Z.; Stoodley, P.; Ehrlich, G.D.; et al. Characterization of Biofilm Matrix, Degradation by DNase Treatment and Evidence of Capsule Downregulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilley, R.P.; Orihuela, C.J. Pneumococci in Biofilms Are Non-Invasive: Implications on Nasopharyngeal Colonization. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Fan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yi, L.; Wang, Y. Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals Genes and Metabolites Involved in Streptococcus suis Biofilm Formation. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Liu, Z.; Yang, K.; Liu, W.; Guo, R.; Li, C.; Tian, Y.; et al. Theaflavin Ameliorates Streptococcus suis-Induced Infection In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, A.I.; Moreno, M.A.; Cebolla, J.A.; González, S.; Latre, M.V.; Domínguez, L.; Fernández-Garayzábal, J.F. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Clinical Strains of Streptococcus suis Isolated from Pigs in Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 105, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruén, C.; Fernandez, A.; Arnal, J.L.; del Pozo, M.; Amoribieta, M.C.; de Blas, I.; Jurado, P.; Calvo, J.H.; Gottschalk, M.; González-Vázquez, L.D.; et al. Genomic and Phenotypic Analysis of Invasive Streptococcus suis Isolated in Spain Reveals Genetic Diversification and Associated Virulence Traits. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechêne-Tempier, M.; Marois-Créhan, C.; Libante, V.; Jouy, E.; Leblond-Bourget, N.; Payot, S. Update on the Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance and the Mobile Resistome in the Emerging Zoonotic Pathogen Streptococcus suis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittiwan, N.; Calland, J.K.; Mourkas, E.; Hitchings, M.D.; Murray, S.; Tadee, P.; Tadee, P.; Duangsonk, K.; Meric, G.; Sheppard, S.K.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Variation in Antimicrobial-Resistance Determinants of Non-Serotype 2 Streptococcus suis Isolates from Healthy Pigs. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongkiettrakul, S.; Maneerat, K.; Arechanajan, B.; Malila, Y.; Srimanote, P.; Gottschalk, M.; Visessanguan, W. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Streptococcus suis Isolated from Diseased Pigs, Asymptomatic Pigs, and Human Patients in Thailand. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenier, D.; Grignon, L.; Gottschalk, M. Characterisation of Biofilm Formation by a Streptococcus suis Meningitis Isolate. Vet. J. 2009, 179, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Shi, Y.; Ji, W.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Sun, J.; Yan, Y. Application of a Bacteriophage Lysin To Disrupt Biofilms Formed by the Animal Pathogen Streptococcus suis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8272–8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaha, H.A.M.; Al-Agamy, M.H.; Soliman, W.E. Antibiotic Effect on Planktonic and Biofilm-Producing Staphylococci. Adv. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dong, C.-L.; Che, R.-X.; Wu, T.; Qu, Q.-W.; Chen, M.; Zheng, S.-D.; Cai, X.-H.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.-H. New Characterization of Multi-Drug Resistance of Streptococcus suis and Biofilm Formation from Swine in Heilongjiang Province of China. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenye, T. Biofilm Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Where Are We and Where Could We Be Going? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e0002423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance and Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms to Antimicrobial Agents—How P. aeruginosa Can Escape Antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dame-Korevaar, A.; Gielen, C.; van Hout, J.; Bouwknegt, M.; Fabà, L.; Vrieling, M. Quantification of Antibiotic Usage against Streptococcus suis in Weaner Pigs in the Netherlands between 2017 and 2021. Prev. Vet. Med. 2025, 235, 106400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Li, J.; Fan, Q.; Mao, C.; Jin, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Grenier, D.; Wang, Y. The otc Gene of Streptococcus suis Plays an Important Role in Biofilm Formation, Adhesion, and Virulence in a Murine Model. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 251, 108925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-B.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Huang, Q.-Y.; Bai, J.-W.; Chen, J.-Q.; Chen, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-H. Emodin Affects Biofilm Formation and Expression of Virulence Factors in Streptococcus suis ATCC700794. Arch. Microbiol. 2015, 197, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, version 13.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Växjö, Sweden, 2023.

- Wijesundara, N.M.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Essential Oils from Origanum Vulgare and Salvia Officinalis Exhibit Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Activities against Streptococcus pyogenes. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 117, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GraphPad Software GraphPad Prism, version 10.5.0; GraphPad Software: San Diego, CA, USA, 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delgado-García, M.; Arenas-Fernández, C.; Mencía-Ares, O.; Manzanares-Vigo, L.; Pastor-Calonge, A.I.; González-Fernández, A.; Gutiérrez-Martín, C.B.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Serovar-Dependent Gene Regulation and Antimicrobial Tolerance in Streptococcus suis Biofilms. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121224

Delgado-García M, Arenas-Fernández C, Mencía-Ares O, Manzanares-Vigo L, Pastor-Calonge AI, González-Fernández A, Gutiérrez-Martín CB, Martínez-Martínez S. Serovar-Dependent Gene Regulation and Antimicrobial Tolerance in Streptococcus suis Biofilms. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121224

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelgado-García, Mario, Carmen Arenas-Fernández, Oscar Mencía-Ares, Lucía Manzanares-Vigo, Ana Isabel Pastor-Calonge, Alba González-Fernández, César B. Gutiérrez-Martín, and Sonia Martínez-Martínez. 2025. "Serovar-Dependent Gene Regulation and Antimicrobial Tolerance in Streptococcus suis Biofilms" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121224

APA StyleDelgado-García, M., Arenas-Fernández, C., Mencía-Ares, O., Manzanares-Vigo, L., Pastor-Calonge, A. I., González-Fernández, A., Gutiérrez-Martín, C. B., & Martínez-Martínez, S. (2025). Serovar-Dependent Gene Regulation and Antimicrobial Tolerance in Streptococcus suis Biofilms. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121224