Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones in Helicobacter pylori Isolates: A Prospective Molecular Analysis in Western Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

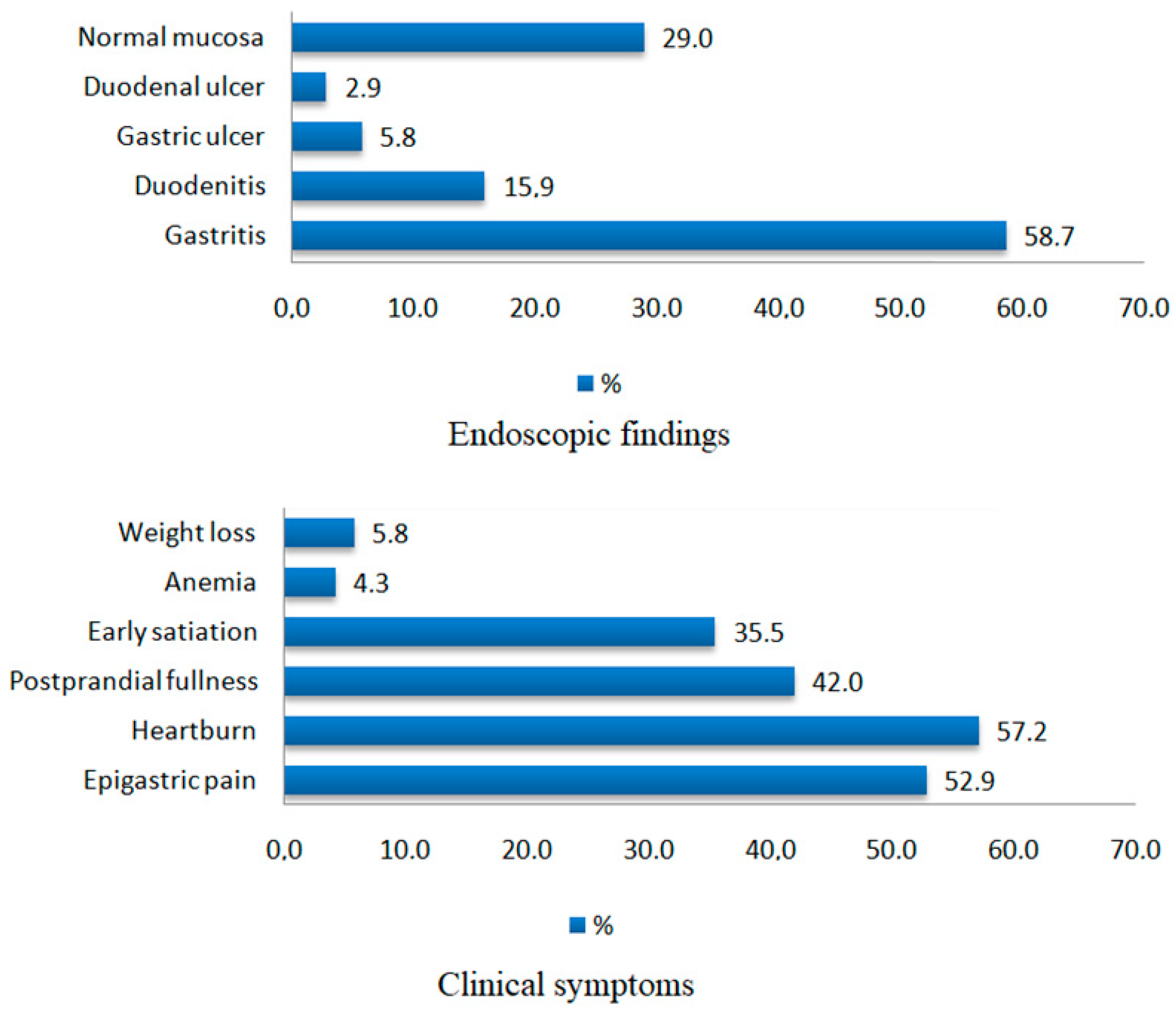

2.1. Baseline Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics of the Study Population

2.2. Resistance to CLA (23S rRNA Mutations)

2.3. Resistance to FQ (gyrA Mutations)

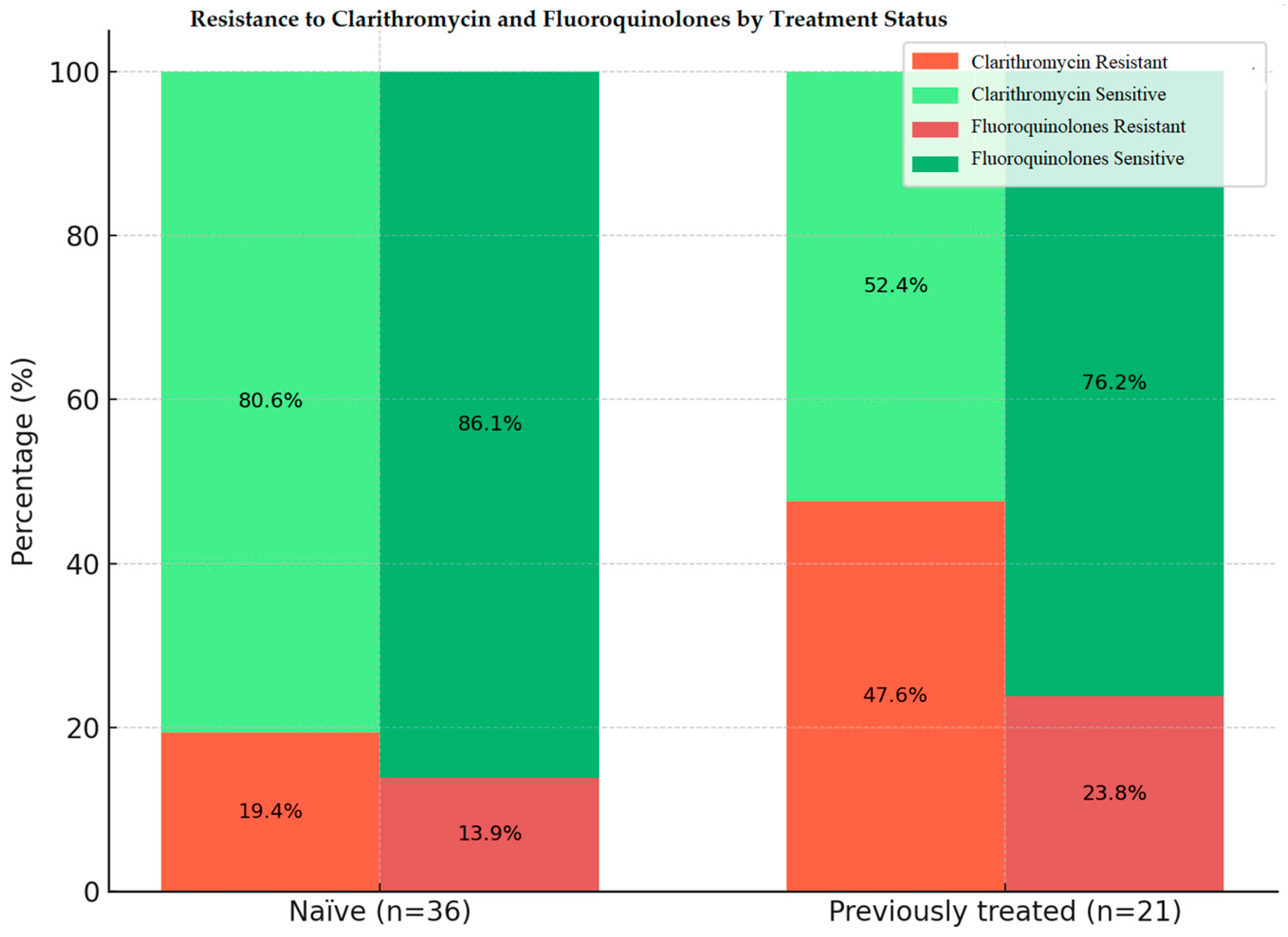

2.4. CLA and FQ Resistance Patterns by Treatment Status

3. Discussion

3.1. Current Findings and Literature Findings

3.2. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design and Ethical Consideration

4.2. Participant Selection and Sample Collection

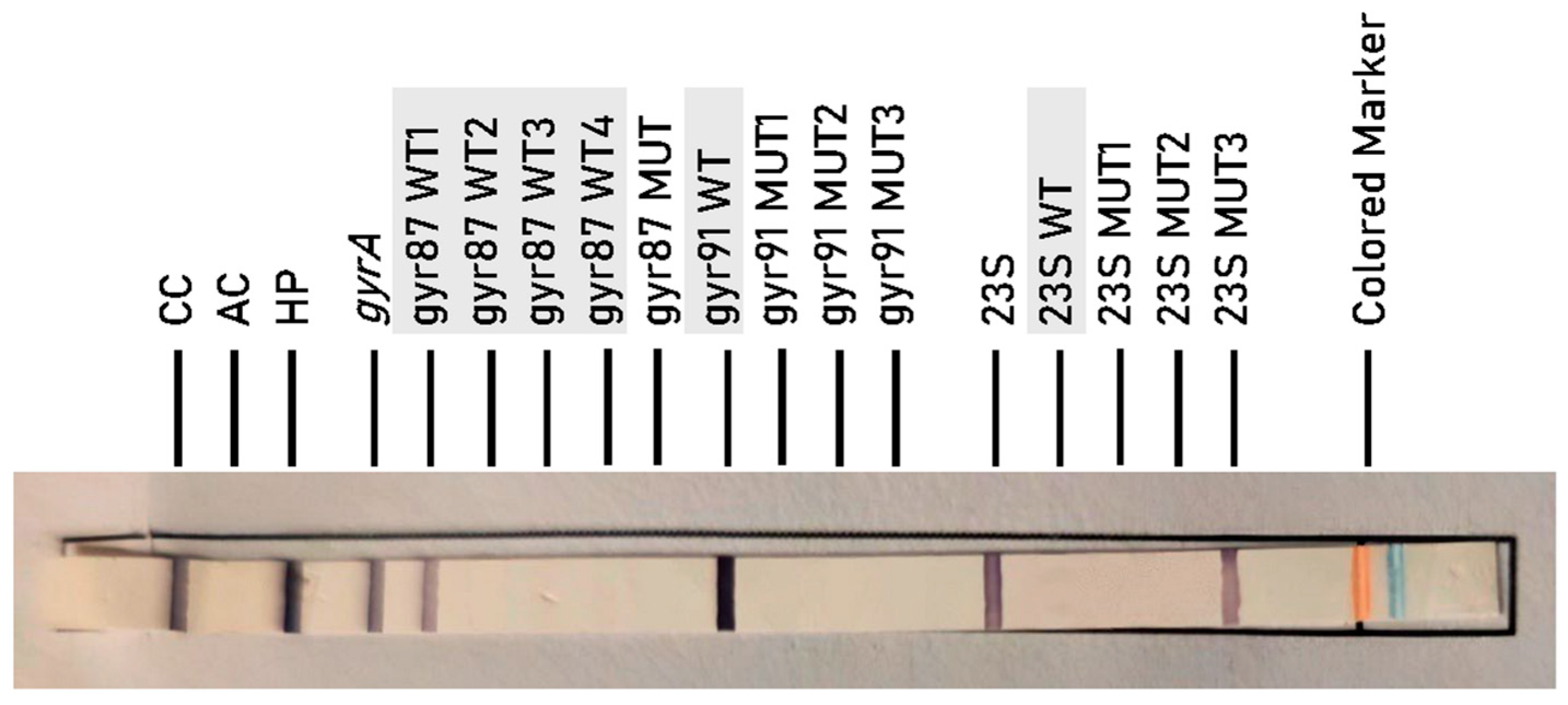

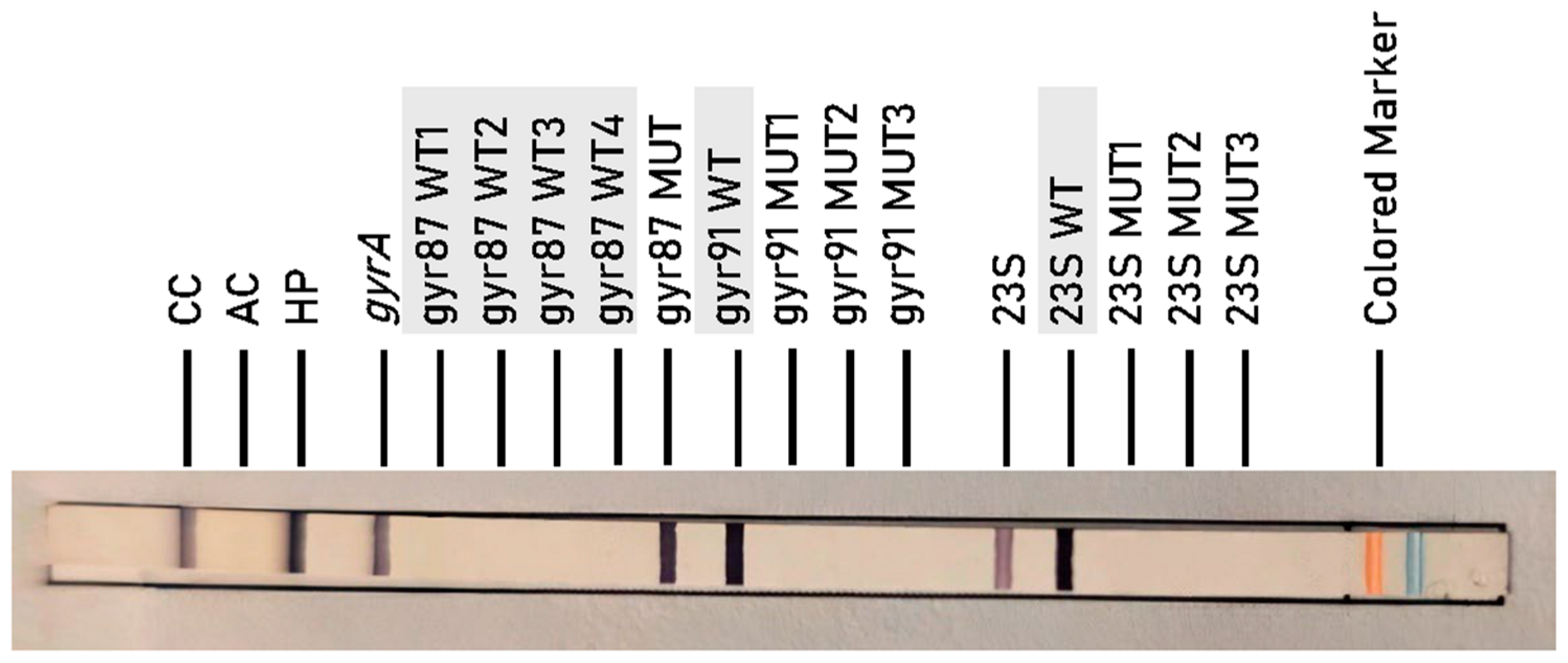

4.3. Molecular Testing

- 23S MUT1: corresponds to mutation A2146G.

- 23S MUT2: corresponds to mutation A2146C.

- 23S MUT3: corresponds to mutation A2147G.

- gyr87 MUT: corresponds to mutations at codon 87-N87K.

- gyr91 MUT1: corresponds to mutation D91N.

- gyr91 MUT2: corresponds to mutation D91G.

- gyr91 MUT3: corresponds to mutation D91Y.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Shi, H.; Zhou, F.; Xie, L.; Lin, R. The Efficacy and Safety of Regimens for Helicobacter pylori Eradication Treatment in China A Systemic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Ebrahimtabar, F.; Zamani, V.; Miller, W.H.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Shokri-Shirvani, J.; Derakhshan, M.H. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: The Worldwide Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Camargo, M.C.; El-Omar, E.; Liou, J.M.; Peek, R.; Schulz, C.; Smith, S.I.; Suerbaum, S. Helicobacter pylori Infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacikowski, T.; Bawa, S.; Gajewska, D.; Myszkowska-Ryciak, J.; Bujko, J.; Rydzewska, G. Current Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients with Dyspepsia Treated in Warsaw, Poland. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2017, 12, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribaldone, D.G.; Zurlo, C.; Fagoonee, S.; Rosso, C.; Armandi, A.; Caviglia, G.P.; Saracco, G.M.; Pellicano, R. A Retrospective Experience of Helicobacter pylori Histology in a Large Sample of Subjects in Northern Italy. Life 2021, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, L.; Tiszai, A.; Kozák, G.; Dóczi, I.; Szekeres, V.; Inczefi, O.; Ollé, G.; Helle, K.; Róka, R.; Rosztóczy, A. Epidemiologic Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Southeast Hungary. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 6365–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, P.; Popa, A.; Bende, R.; Miutescu, B.; Mare, R.; Borlea, A.; Aragona, G.; Groza, A.L.; Serena, L.; Popescu, A.; et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Efficacy of Bismuth Quadruple and Levofloxacin Triple Eradication Therapies: A Retrospective Analysis. Life 2024, 14, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, P.; Miutescu, B.; Gadour, E.; Burciu, C.; Mare, R.; Bende, R.; Seclăman, E.; Aragona, G.; Serena, L.; Sirli, R. Delayed Diagnosis and Evolving Trends in Gastric Cancer During and After COVID-19: A Comparative Study of Staging, Helicobacter pylori Infection and Bleeding Risk in Western Romania. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.Y.; Leung, W.K.; Cheung, K.S. Antibiotic Resistance, Susceptibility Testing and Stewardship in Helicobacter pylori Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, N.; Yilmaz, Ö.; Demiray-Gürbüz, E. Importance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for the Management of Eradication in Helicobacter pylori Infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 2854–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; Rokkas, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Liou, J.M.; Schulz, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Hunt, R.H.; Leja, M.; O’Morain, C.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection: The Maastricht VI/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2022, 71, 1724–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Qian, X.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.P.; Song, C.; Wu, S.; An, Y.; Yuan, R.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y. The Effect of Antibiotic Resistance on Helicobacter pylori Eradication Efficacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Helicobacter 2020, 25, e12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P. Empirical or Susceptibility-Guided Treatment for Helicobacter pylori Infection? A Comprehensive Review. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820968736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, A.N.; Theel, E.S.; Cole, N.C.; Rothstein, T.E.; Gordy, G.G.; Patel, R. Testing for Helicobacter pylori in an Era of Antimicrobial Resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0073223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracino, I.M.; Pavoni, M.; Zullo, A.; Fiorini, G.; Lazzarotto, T.; Borghi, C.; Vaira, D. Next Generation Sequencing for the Prediction of the Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori: A Literature Review. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, J.S.; Tanoeiro, L.; Lopes-Oliveira, R.; Vale, F.F. Biomarker Characterization and Prediction of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance from Helicobacter pylori Next Generation Sequencing Data. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumra, S.; Ray, A. Recent Advances in Helicobacter pylori Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management: A Comprehensive Review. Explor. Dig. Dis. 2025, 4, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C.B.; Herzlinger, M.I.; Moss, S.F. Helicobacter pylori Antimicrobial Resistance and the Role of Next-Generation Sequencing. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 20, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Erin, B.; Ilaria, S.; Giulia, F.; Courtney, C.; Vladimir, S.; Denise, P.; Clarissa, G.; Reddy, P.; Vecheslav, E.; Dino, V. A Novel Stool PCR Test for Helicobacter pylori May Predict Clarithromycin Resistance and Eradication of Infection at a High Rate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2400–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, L.; Andrea, S.; Klaus, P.; Sibylle, K.; Holger, R. Evaluation of the Novel Helicobacter pylori ClariRes Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection and Clarithromycin Susceptibility Testing of H. pylori in Stool Specimens from Symptomatic Children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 1718–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambau, E.; Allerheiligen, V.; Coulon, C.; Corbel, C.; Lascols, C.; Deforges, L.; Soussy, C.J.; Delchier, J.C.; Megraud, F. Evaluation of a New Test, Genotype HelicoDR, for Molecular Detection of Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3600–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mégraud, F. H pylori Antibiotic Resistance: Prevalence, Importance, and Advances in Testing. Gut 2004, 53, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.T.; Vítor, J.M.B.; Santos, A.; Oleastro, M.; Vale, F.F. Trends in Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Clarithromycin: From Phenotypic to Genomic Approaches. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, e000344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, T.; Suzuki, H.; Umezawa, A.; Muraoka, H.; Iwasaki, E.; Masaoka, T.; Kobayashi, I.; Hibi, T. Rapid Detection of Point Mutations Conferring Resistance to Fluoroquinolone in GyrA of Helicobacter pylori by Allele-Specific PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardos, I.A.; Zaha, D.C.; Sindhu, R.K.; Cavalu, S. Revisiting Therapeutic Strategies for H. pylori Treatment in the Context of Antibiotic Resistance: Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies. Molecules 2021, 26, 6078. [Google Scholar]

- Elbaiomy, R.G.; Luo, X.; Guo, R.; Deng, S.; Du, M.; El-Sappah, A.H.; Bakeer, M.; Azzam, M.M.; Elolimy, A.A.; Madkour, M.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori: A Genetic and Physiological Perspective. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoldi, A.; Carrara, E.; Graham, D.Y.; Conti, M.; Tacconelli, E. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in World Health Organization Regions. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1372–1382.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corojan, A.; Dumitrașcu, D.; Ciobanca, P.; Leucuta, D. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection among Dyspeptic Patients in Northwestern Romania: A Decreasing Epidemiological Trend in the Last 30 years. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 3488–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olar, L.; Mitrut, P.; Florou, C.; Mălăescu, G.D.; Predescu, O.I.; Rogozea, L.M.; Mogoantă, L.; Ionovici, N.; Pirici, I. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients with Eso-Gastro-Duodenal Pathology. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2017, 58, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borka Balas, R.; Meliț, L.E.; Mărginean, C.O. Worldwide Prevalence and Risk Factors of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children. Children 2022, 9, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, O.P.; Bordin, D.; Tepes, B.; Pérez-Aisa, Á.; Vaira, D.; Caldas, M.; Bujanda, L.; Castro-Fernandez, M.; Lerang, F.; Leja, M.; et al. European Registry on Helicobacter pylori Management (Hp-EuReg): Patterns and Trends in First-Line Empirical Eradication Prescription and Outcomes of 5 Years and 21 533 Patients. Gut 2021, 70, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priadko, K.; Gibaud, S.A.; Druet, A.; Galmiche, L.; Megraud, F.; Corvec, S.; Matysiak-Budnik, T. Real-Time PCR Helicobacter pylori Test in Comparison With Culture and Histology for Helicobacter pylori Detection and Identification of Resistance to Clarithromycin: A Single-Center Real-Life Study. Helicobacter 2025, 30, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saracino, I.M.; Fiorini, G.; Zullo, A.; Pavoni, M.; Saccomanno, L.; Vaira, D. Trends in Primary Antibiotic Resistance in H. pylori Strains Isolated in Italy between 2009 and 2019. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megraud, F.; Bruyndonckx, R.; Coenen, S.; Wittkop, L.; Huang, T.D.; Hoebeke, M.; Bénéjat, L.; Lehours, P.; Goossens, H.; Glupczynski, Y.; et al. Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Antibiotics in Europe in 2018 and Its Relationship to Antibiotic Consumption in the Community. Gut 2021, 70, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costache, C.; Colosi, H.A.; Grad, S.; Paștiu, A.I.; Militaru, M.; Hădărean, A.P.; Țoc, D.A.; Neculicioiu, V.S.; Baciu, A.M.; Opris, R.V.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori Isolates from Northwestern and Central Romania Detected by Culture-Based and PCR-Based Methods. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.Q.H.; Ha, T.M.T.; Nguyen, S.T.; Le, N.D.K.; Nguyen, T.M.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Pham, T.T.H.; Tran, V.H. High Rates of Clarithromycin and Levofloxacin Resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Patients with Chronic Gastritis in the South East Area of Vietnam. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsmár, É.; Buzás, G.M.; Szirtes, I.; Kocsmár, I.; Kramer, Z.; Szijártó, A.; Fadgyas-Freyler, P.; Szénás, K.; Rugge, M.; Fassan, M.; et al. Primary and Secondary Clarithromycin Resistance in Helicobacter pylori and Mathematical Modeling of the Role of Macrolides. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierardi, E.; Giorgio, F.; Losurdo, G.; Di Leo, A.; Principi, M. How Antibiotic Resistances Could Change Helicobacter pylori Treatment: A Matter of Geography? World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 8168–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastukh, N.; Binyamin, D.; On, A.; Paritsky, M.; Peretz, A. GenoType® HelicoDR Test in Comparison with Histology and Culture for Helicobacter pylori Detection and Identification of Resistance Mutations to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones. Helicobacter 2017, 22, e12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binyamin, D.; Pastukh, N.; On, A.; Paritsky, M.; Peretz, A. Phenotypic and Genotypic Correlation as Expressed in Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones. Gut Pathog. 2017, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miendje Deyi, V.Y.; Burette, A.; Bentatou, Z.; Maaroufi, Y.; Bontems, P.; Lepage, P.; Reynders, M. Practical Use of GenoType® HelicoDR, a Molecular Test for Helicobacter pylori Detection and Susceptibility Testing. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodunova, N.; Tsapkova, L.; Polyakova, V.; Baratova, I.; Rumyantsev, K.; Dekhnich, N.; Nikolskaya, K.; Chebotareva, M.; Voynovan, I.; Parfenchikova, E.; et al. Genetic Markers of Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Clarithromycin and Levofloxacin in Moscow, Russia. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6665–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, B.S.; Martins, G.M.; Lima, K.; Cota, B.; Moretzsohn, L.D.; Ribeiro, L.T.; Breyer, H.P.; Maguilnik, I.; Maia, A.B.; Rezende-Filho, J.; et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones in Brazil: A National Survey. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, K.; Wagner, K.; Keller, P.M.; Risch, L.; Risch, M.; Bodmer, T. Comparison of the Diagnostic Performance of QPCR, Sanger Sequencing, and Whole-Genome Sequencing in Determining Clarithromycin and Levofloxacin Resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 596371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medakina, I.; Tsapkova, L.; Polyakova, V.; Nikolaev, S.; Yanova, T.; Dekhnich, N.; Khatkov, I.; Bordin, D.; Bodunova, N. Helicobacter pylori Antibiotic Resistance: Molecular Basis and Diagnostic Methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Raymond, J.; Garnier, M.; Cremniter, J.; Burucoa, C. Distribution of Spontaneous GyrA Mutations in 97 Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Helicobacter pylori Isolates Collected in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 550–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, J.M.; Yano, Y.; Okamoto, A.; Matsuda, R.; Shiraishi, M.; Hashimoto, Y.; Morita, N.; Takeuchi, H.; Suganuma, N.; Takeuchi, H. Evidence of Helicobacter pylori Heterogeneity in Human Stomachs by Susceptibility Testing and Characterization of Mutations in Drug-Resistant Isolates. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhang, W.; Ru, S.; Liu, Y.; Du, K.; Jiang, F. Antibiotic Heteroresistance: An Important Factor in the Failure of Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 51, 1330–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Gong, X.L.; Liu, D.W.; Zeng, R.; Zhou, L.F.; Sun, X.Y.; Liu, D.S.; Xie, Y. Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori Heteroresistance in Gastric Biopsies and Its Clinical Relevance. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 819506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsmár, É.; Kocsmár, I.; Buzás, G.M.; Szirtes, I.; Wacha, J.; Takáts, A.; Hritz, I.; Schaff, Z.; Rugge, M.; Fassan, M.; et al. Helicobacter pylori Heteroresistance to Clarithromycin in Adults—New Data by in Situ Detection and Improved Concept. Helicobacter 2020, 25, e12670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotype | No. of Specimens | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | Previously Treated | ||

| 23S WT (positions 2146–2147) | 29 | 11 | 70.2% |

| 23S MUT3 (A2147G) | 7 | 10 | 29.8% |

| Total | 36 | 21 | 100% |

| Genotype | No. of Specimens | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | Previously Treated | ||

| gyr 87WT 1-4 + gyr91WT | 31 | 16 | 82.5% |

| gyr87MUT | 3 | 2 | 8.8% |

| gyr91MUT1 | 1 | 1 | 3.5% |

| gyr87WT2 + gyr87MUT | 1 | 0 | 1.7% |

| gyr87WT1 + gyr87MUT | 0 | 2 | 3.5% |

| Total | 36 | 21 | 100% |

| Group (n) | CLA Sensitive n (%) | CLA Resistant n (%) | FQ Sensitive n (%) | FQ Resistant n (%) | p-Value CLA S vs. R | p-Value (FQ S vs. R) | p-Value (Naïve vs. Treated Between Groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive to treatment | 29 (80.6) | 7 (19.4) | 31 (86.1) | 5 (13.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | CLA R: p = 0.018; FQ R: p = 0.557 |

| Previously treated | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | 16 (76.2) | 5 (23.8) | 0.124 | 0.002 | CLA S: p = 0.018; FQ S: p = 0.557 |

| Total | 40 (70.2) | 17 (29.8) | 47 (82.5) | 10 (17.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serena, P.; Mare, R.; Miutescu, B.; Bende, R.; Popa, A.; Aragona, G.; Seclăman, E.; Serena, L.; Barbulescu, A.; Sirli, R. Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones in Helicobacter pylori Isolates: A Prospective Molecular Analysis in Western Romania. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121223

Serena P, Mare R, Miutescu B, Bende R, Popa A, Aragona G, Seclăman E, Serena L, Barbulescu A, Sirli R. Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones in Helicobacter pylori Isolates: A Prospective Molecular Analysis in Western Romania. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121223

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerena, Patricia, Ruxandra Mare, Bogdan Miutescu, Renata Bende, Alexandru Popa, Giovanni Aragona, Edward Seclăman, Luca Serena, Andreea Barbulescu, and Roxana Sirli. 2025. "Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones in Helicobacter pylori Isolates: A Prospective Molecular Analysis in Western Romania" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121223

APA StyleSerena, P., Mare, R., Miutescu, B., Bende, R., Popa, A., Aragona, G., Seclăman, E., Serena, L., Barbulescu, A., & Sirli, R. (2025). Resistance to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones in Helicobacter pylori Isolates: A Prospective Molecular Analysis in Western Romania. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121223