The Cost of Resource Use Relative to the Development of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in a Tertiary Cancer Setting in Qatar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Demographics

2.2. Classification of Antimicrobials

2.3. Economic Analysis

2.3.1. Cost Savings with Antimicrobial Consumption

2.3.2. Cost Savings with Resource Utilization

2.3.3. Cost Avoidance

2.3.4. Operational Cost

2.3.5. Overall Difference in Cost of Resource Use

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis

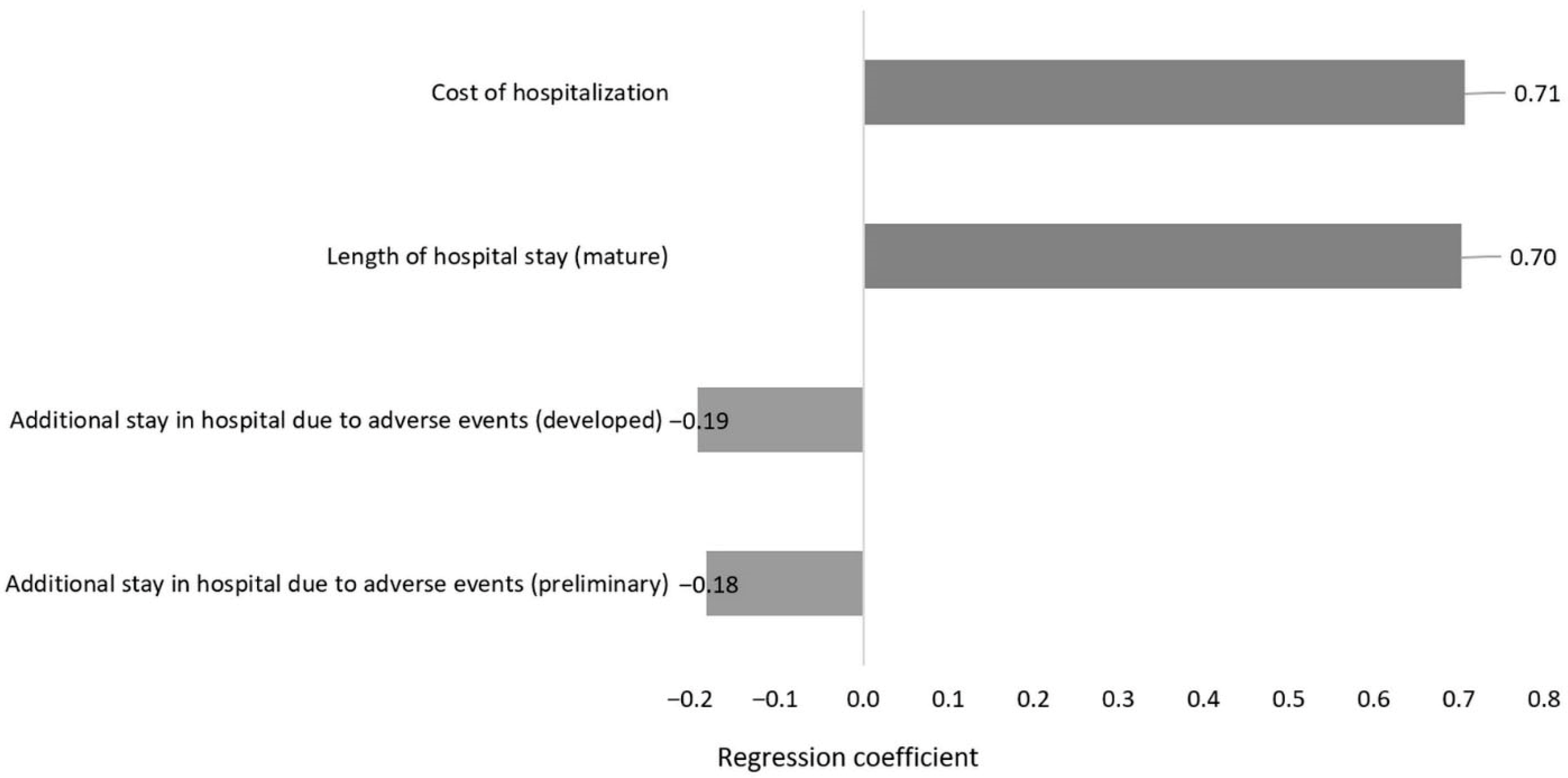

2.4.1. One-Way Sensitivity Analysis

2.4.2. Multivariate Sensitivity Analysis

2.5. Secondary Outcomes (Clinical Outcomes)

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Study Design and ASP Description

4.2. Study Setting

4.3. Study Population

4.4. Sample Size

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.6. Outcome Measures

4.6.1. Primary Outcome

4.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

- All-cause death within 30 days of hospitalization.

- Infection-related death, defined as a death that occurred within 30 days of hospitalization, where the primary or contributing cause was recorded as an infection in the electronic medical record (Cerner®), based on physician notes, microbiology results, or reviews by infectious disease consultants.

- Infection-related readmission, defined as any hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge with a documented infection diagnosis or a positive microbiological culture that required antimicrobial therapy.

- Occurrence of hospital-onset CDI.

- Duration of hospital stay due to infection-related reasons.

- ADEs associated with antimicrobials. ADEs were identified based on documented adverse reactions or clinical notes indicating toxicity linked to antimicrobial therapy, in line with definitions from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) [35,36]. ADEs were recognized when a temporal relationship between antimicrobial administration and the onset of adverse clinical manifestations (such as rash, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, cytopenia, or gastrointestinal disturbances) was recorded in the patient’s electronic medical record (Cerner®) by the treating physician or the infectious disease consultant. Documentation sources included progress notes, medication-related alerts, and laboratory values indicating drug-related toxicity (e.g., elevated creatinine levels with nephrotoxic antibiotics). Events labeled as “suspected adverse drug reaction,” “toxicity,” or “treatment-related complication” were also classified as ADEs. Development of antimicrobial resistance during hospitalization.

4.7. The Change in Monetary Value of Resource Use

4.7.1. Cost Saving

- The reduction in therapy cost because of an assumed reduction in antimicrobial consumption with the developed ASP relative to the preliminary ASP was measured using DDD [37]. The DDD is defined as the dose of medication most commonly used for the most common indication in adults. An assumed reduction in the overall resource utilization cost with the developed ASP relative to the preliminary ASP was measured. The total financial cost of resources for each patient was calculated based on micro-costing, utilizing the unit cost of specific resources and their utilization frequency. Resource use of interest was related to reduced usage of diagnostic, laboratory, and culture tests, as well as a transition from intravenous (IV) to oral medication during the initial three days of antibiotic therapy.

4.7.2. Cost Avoidance

- The length of hospitalization and the hospital readmission of interest in the study were those deemed to be infection-related and/or relevant to the use of antimicrobials. The total cost of hospitalization length was determined by multiplying the daily cost of hospitalization by the number of hospitalization days for each patient.

- In line with the above, microeconomic analysis of individual-level resource utilization was also applied to calculate CDI costs. The overall cost of CDI was derived based on the unit cost of CDI diagnosis and care. Standard care for CDI consisted in vancomycin 125 mg orally four times daily for ten days, assuming all CDI patients underwent CDI cultures [38].

- Based on expert consensus in the current study and relevant to previous studies [39], the cost of an ADE was calculated on the conservative assumption that any injectable or non-injectable antimicrobials will lead to an additional 2 days or 1 day of hospital stay in the relevant unit, respectively.

4.7.3. Operational Cost

- With the preliminary ASP, the program comprised the costs of one physician and one clinical pharmacist spending five hours in monthly committee meetings. Additionally, there are the costs of one clinical pharmacist and one physician spending three hours daily on data collection, as well as the cost of one physician spending one hour daily in clinical rounds.

- With the developed ASP, the program comprised the costs of an infectious disease consultant, a clinical pharmacist, a clinical microbiologist, an infection control practitioner, and a nurse spending ten hours monthly in meetings. Also included are the costs of one physician fellow and one clinical pharmacist spending three hours daily on data collection and one hour daily in clinical rounds.

4.8. Cost Data

4.9. Sensitivity Analysis

- A one-way sensitivity analysis assessed the impact of uncertainty in specific inputs on study conclusions, where values of uncertain input variables were each substituted with new values, for an input variable at a time. Targeted inputs in the analysis were the cost of hospitalization, length of initial admission, and length of additional hospital stays due to ADEs, with each assigned a 20% uncertainty range.

- Multivariate sensitivity analysis was conducted by simultaneously targeting various underlying uncertain inputs, simulating real-life uncertainty. Here, the cost of hospitalization, length of initial admission, and additional hospital stays due to ADEs were of interest. Each input was varied within a ±10% uncertainty range.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schuts, E.C.; Hulscher, M.; Mouton, J.W.; Verduin, C.M.; Stuart, J.; Overdiek, H.; van der Linden, P.D.; Natsch, S.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Wolfs, T.F.W.; et al. Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljayyousi, G.F.; Abdel-Rahman, M.E.; El-Heneidy, A.; Kurdi, R.; Faisal, E. Public practices on antibiotic use: A cross-sectional study among Qatar University students and their family members. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, P.; Sneddon, J.; Nathwani, D. Overview of strategies for overcoming the challenge of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 3, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratti, V.F.; Wilson, B.E.; Fazelzad, R.; Pabani, A.; Zurn, S.J.; Johnson, S.; Sung, L.; Rodin, D. Scoping review protocol on the impact of antimicrobial resistance on cancer management and outcomes. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikhan, F.; Rawaf, S.; Majeed, A.; Hassounah, S. Knowledge, attitude, perception and practice regarding antimicrobial use in upper respiratory tract infections in Qatar: A systematic review. JRSM Open 2018, 9, 2054270418774971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC CfDCaP. 1 in 3 Antibiotic Prescriptions Unnecessary. 2022. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/media/releases/2016/p0503-unnecessary-prescriptions.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Dellit, T.H.; Owens, R.C.; McGowan, J.E.; Gerding, D.N.; Weinstein, R.A.; Burke, J.P.; Huskins, W.C.; Paterson, D.L.; Fishman, N.O.; Carpenter, C.F.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coast, J.; Smith, R.D.; Millar, M.R. Superbugs: Should antimicrobial resistance be included as a cost in economic evaluation? Health Econ. 1996, 5, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratore, E.; Baccelli, F.; Leardini, D.; Campoli, C.; Belotti, T.; Viale, P.; Prete, A.; Pession, A.; Masetti, R.; Zama, D. Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions in Pediatric Oncology: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, M.; Mamdani, M.M.; Morris, A.M.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Broady, R.; Deotare, U.; Grant, J.; Kim, D.; Schimmer, A.; Schuh, A.; et al. Effect of an antimicrobial stewardship programme on antimicrobial utilisation and costs in patients with leukaemia: A retrospective controlled study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad Medical Corporation. 2022. Available online: https://www.hamad.qa/EN/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Nathwani, D.; Varghese, D.; Stephens, J.; Ansari, W.; Martin, S.; Charbonneau, C. Value of hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs [ASPs]: A systematic review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.E. What is value in health care? N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsuhibani, A.A.; Alobaid, N.A.; Alahmadi, M.H.; Alqannas, J.S.; Alfreaj, W.S.; Albadrani, R.F.; Alamer, K.A.; Almogbel, Y.S.; Alhomaidan, A.; Guo, J.J. Antifungal Agents’ Trends of Utilization, Spending, and Prices in the US Medicaid Programs: 2009–2023. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskovaty, A.; Pflomm, J.; Myke, N.; Seo, S. A multidisciplinary approach to antimicrobial stewardship: Evolution into the 21st century. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, E.; Dupont, H.; Tabah, A.; Lortholary, O.; Stahl, J.P.; Francais, A.; Martin, C.; Guidet, B.; Timsit, J.-F. Systemic antifungal therapy in critically ill patients without invasive fungal infection. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, E.; Nguyen, M.; Allen, M.; Clark, C.M.; Jacobs, D.M. A systematic review of the impact of antifungal stewardship interventions in the United States. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2019, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satzke, C.; Turner, P.; Virolainen-Julkunen, A.; Adrian, P.V.; Antonio, M.; Hare, K.M.; Henao-Restrepo, A.M.; Leach, A.J.; Klugman, K.P.; Porter, B.D.; et al. Standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Updated recommendations from the World Health Organization Pneumococcal Carriage Working Group. Vaccine 2013, 32, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, J.W.; Hendrix, R.; Poelman, R.; Niesters, H.G.; Postma, M.J.; Sinha, B.; Friedrich, A.W. Measuring the impact of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2016, 14, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hadi, H.; Eltayeb, F.; Al Balushi, S.; Daghfal, J.; Ahmed, F.; Mateus, C. Evaluation of Hospital Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Implementation, Process, Impact, and Outcomes, Review of Systematic Reviews. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushanab, D.; Al-Marridi, W.; Al Hail, M.; Abdul Rouf, P.V.; ElKassem, W.; Thomas, B.; Alsoub, H.; Ademi, Z.; Hanssens, Y.; Enany, R.E.; et al. The cost associated with the development of the antimicrobial stewardship program in the adult general medicine setting in Qatar. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2024, 17, 2326382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.; Gladstone, B.P.; Burkert, F.; Carrara, E.; Foschi, F.; Döbele, S.; Tacconelli, E. Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, D.L.; Bisno, A.L.; Chambers, H.F.; Everett, E.D.; Dellinger, P.; Goldstein, E.J.; Gorbach, S.L.; Hirschmann, J.V.; Kaplan, E.L.; Montoya, J.G.; et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 1373–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.M.; Patel, P.R.; Kallen, A.J.; Strom, J.A.; Tucker, J.K.; D’Agata, E.M. Antimicrobial use in outpatient hemodialysis units. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Wellcome Trust: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, C.; Binda, F.; Lamkang, A.S.; Trett, A.; Charani, E.; Goff, D.A.; Harbarth, S.; Hinrichsen, S.; Levy-Hara, G.; Mendelson, M.; et al. Developing core elements and checklist items for global hospital antimicrobial stewardship programmes: A consensus approach. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlam, T.F.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Abbo, L.M.; MacDougall, C.; Schuetz, A.N.; Septimus, E.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Dellit, T.H.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Fishman, N.O.; et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e51–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.P.; Gooch, M. Long-term effects of an antimicrobial stewardship programme at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, Z.G.; Jibril, F.; Elmekaty, E.; Sonallah, H.; Chahine, E.B.; AlNajjar, A. Assessment of antimicrobial stewardship programs within governmental hospitals in Qatar: A SWOC analysis. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 29, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SHEA/IDSA Clinical Practice Guidelines for Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program. 2016. Available online: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/implementing-an-ASP/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Malani, A.N.; Richards, P.G.; Kapila, S.; Otto, M.H.; Czerwinski, J.; Singal, B. Clinical and economic outcomes from a community hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship program. Am. J. Infect. Control 2013, 41, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebaaly, J.; Parsons, L.B.; Pilch, N.A.; Bullington, W.; Hayes, G.L.; Piasterling, H. Clinical and financial impact of pharmacist involvement in discharge medication reconciliation at an academic medical center: A prospective pilot study. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 50, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, J.; Byrne, S.; Woods, N.; Lynch, D.; McCarthy, S. Cost-outcome description of clinical pharmacist interventions in a university teaching hospital. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branham, A.R.; Katz, A.J.; Moose, J.S.; Ferreri, S.P.; Farley, J.F.; Marciniak, M.W. Retrospective analysis of estimated cost avoidance following pharmacist-provided medication therapy management services. J. Pharm. Pract. 2013, 26, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Safety of Medicines—Adverse Drug Reactions. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/medicines/safety-of-medicines--adverse-drug-reactions-jun18.pdf?sfvrsn=4fcaf40_2 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. Available online: https://www.nccmerp.org/sites/default/files/nccmerp-25-year-report.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- WHO. ATC/DDD Index 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Johnson, S.; Lavergne, V.; Skinner, A.M.; Gonzales-Luna, A.J.; Garey, K.W.; Kelly, C.P.; Wilcox, M.H. Clinical practice guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 focused update guidelines on management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e1029–e1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-C.; Hsiao, F.-Y.; Shen, L.-J.; Wu, C.-C. The cost-saving effect and prevention of medication errors by clinical pharmacist intervention in a nephrology unit. Medicine 2017, 96, e7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Preliminary ASP (n = 81) | Developed ASP (n = 105) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 54 (66.7) | 49 (46.7) | 0.008 |

| Female | 27 (33.3) | 56 (53.3) | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 47.8 ± 17.62 | 54.7 ±19.89 | 0.015 |

| Weight, mean ± SD | 67.18 ± 23 | 73 ± 27.3 | 0.158 |

| Nationality, n (%) | |||

| Arab | 48 (59.3) | 77 (73.3) | 0.115 |

| Asian (non-Arab) | 30 (37) | 28 (26.7) | |

| Western | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| African (non-Arab) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Allergy, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (1.2) | 73 (29.3) | 0.074 |

| No | 81(98.8) | 176 (70.7) | |

| Class of medications, n (%) | |||

| Antibacterial | 7 (8.6) | 99 (94.3) | <0.001 |

| Antifungal | 74 (91.4) | 6 (5.7) | |

| Number of medications received n (%) | |||

| 1 | 56 (69.1) | 101 (96.2) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 20 (24.7) | 2 (1.9) | |

| 3 or more | 5 (6.2) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Location of infection, n (%) | |||

| Neck | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 2 (2.5) | 11 (10.5) | |

| Respiratory | 4 (4.9) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (3.7) | 9 (8.6) | |

| Abdomen | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Genitourinary | 1 (1.2) | 22 (43.1) | |

| Blood | 36 (44.4) | 36 (34.3) | |

| unknown | 33 (40.7) | 25 (23.8) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 36 (34.3) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 32 (39.5) | 23 (21.9) | |

| Moderate | 16 (19.8) | 17 (16.2) | |

| Severe | 33 (40.7) | 29 (27.6) | |

| Resource | Preliminary ASP | Developed ASP |

|---|---|---|

| Value of resource utilization, QAR (USD) | ||

| Culture performance before receiving therapy | 640 (USD 18) | 720 (USD 198) |

| Laboratory test performance before receiving therapy | 24,730 (USD 6794) | 28,892 (USD 7937) |

| Biopsy performance before receiving therapy | 0 | 0 |

| Culture performance after receiving therapy | 2880 (USD 791) | 2943 (USD 809) |

| Laboratory test performance after receiving therapy | 28,994 (USD 7966) | 37,641 (USD 10,341) |

| Biopsy performance after receiving therapy | 0 | 0 |

| Switching from IV to oral | 68,001 (USD 18,682) | 75,760 (USD 20,813) |

| Total cost | 125,245 (USD 34,408) | 145,956 (USD 40,098) |

| Cost saving,in favor of preliminary ASP | Negative 20,711 (USD 5689) | |

| Cost per patient | 1546 (USD 423) | 1390 (USD 381) |

| Cost saving,in favor of developed ASP (per patient) | Positive 156 (USD 43) | |

| Cost avoidance (QAR, USD) | ||

| Hospitalization | 16,827,888 (USD 4,623,046) | 4,567,221 (USD 1,254,731) |

| Clostridium difficile infection and its management | 5050 (USD 1387) | 3536 (USD 988) |

| Rehospitalization within 30 days | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse drug events | 1,086,868 (USD 298,590) | 1,379,108 (USD 378,876) |

| Total cost | 17,919,806 (USD 4,923,023) | 5,950,155 (USD 1,634,657) |

| Cost avoided, in favor of developed ASP | Positive 11,969,651 (USD 3,288,365) | |

| Cost per patient | 221,232 (USD 60,612) | 56,668 (USD 15,526) |

| Cost avoided, in favor of developed ASP (per patient) | Positive 164,564 (USD 45,086) | |

| Parameter | Total Value Difference in Favor of Developed ASP QAR (USD) | Value Difference in Favor of Developed ASP per Patient QAR (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost saving in terms of DDDs | 1,269,378 (USD 348,730) | 16,519 (USD 4526) |

| Cost saving in terms of resource utilization | Negative 20,711 (USD 5689) | Positive 156 (USD 43) |

| Total cost saving | 1,248,666 (USD 345,151) | 16,675 (USD 4568) |

| Cost avoidance | 11,969,651 (USD 3,288,366) | 164,564 (USD 45,086) |

| Operational cost | Positive 12,477 (USD 3428) | Positive 329 (USD 90) |

| Net reduction in monetary spending | 13,205,840 (USD 3,618,038) | 180,910 (USD 49,564) |

| Variable | Preliminary ASP (n = 81) | Developed ASP (n = 105) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of hospital stay (initial disposition), mean ± SD | 34.02 ± 51.21 | 7.12 ± 10.47 | <0.001 |

| Readmission, n (%) | |||

| Length of hospital stay (second disposition), mean ± SD | 0 | 0 | |

| All-cause death, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (1.2) | 7 (2.8) | 0.46 |

| No | 80 (98.8) | 242 (97.2) | |

| Infection-related death, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| No | 81 (100) | 105 (100) | |

| Infection resistance, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| No | 81 (100) | 105 (100) | |

| Clostridioides difficile, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 25 (30.9) | 16 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| No | 56 (69.1) | 89 (84.8) | |

| Adverse drug events, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| No | 81 (100) | 105 (100) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abushanab, D.; Alhaj Moustafa, D.; Hamad, A.; Sankar, B.A.; Nasr, Z.G.; Alsoub, H.; Al-Badriyeh, D. The Cost of Resource Use Relative to the Development of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in a Tertiary Cancer Setting in Qatar. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121204

Abushanab D, Alhaj Moustafa D, Hamad A, Sankar BA, Nasr ZG, Alsoub H, Al-Badriyeh D. The Cost of Resource Use Relative to the Development of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in a Tertiary Cancer Setting in Qatar. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121204

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbushanab, Dina, Diala Alhaj Moustafa, Anas Hamad, Bhagyasree Adampally Sankar, Ziad G. Nasr, Hussam Alsoub, and Daoud Al-Badriyeh. 2025. "The Cost of Resource Use Relative to the Development of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in a Tertiary Cancer Setting in Qatar" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121204

APA StyleAbushanab, D., Alhaj Moustafa, D., Hamad, A., Sankar, B. A., Nasr, Z. G., Alsoub, H., & Al-Badriyeh, D. (2025). The Cost of Resource Use Relative to the Development of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in a Tertiary Cancer Setting in Qatar. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121204