Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage (DASC) and Oral Antimicrobial-Use Trends at a Community Pharmacy in Japan: A 2018–2023 Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Period

2.2. Antimicrobial Use Metric Calculation

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

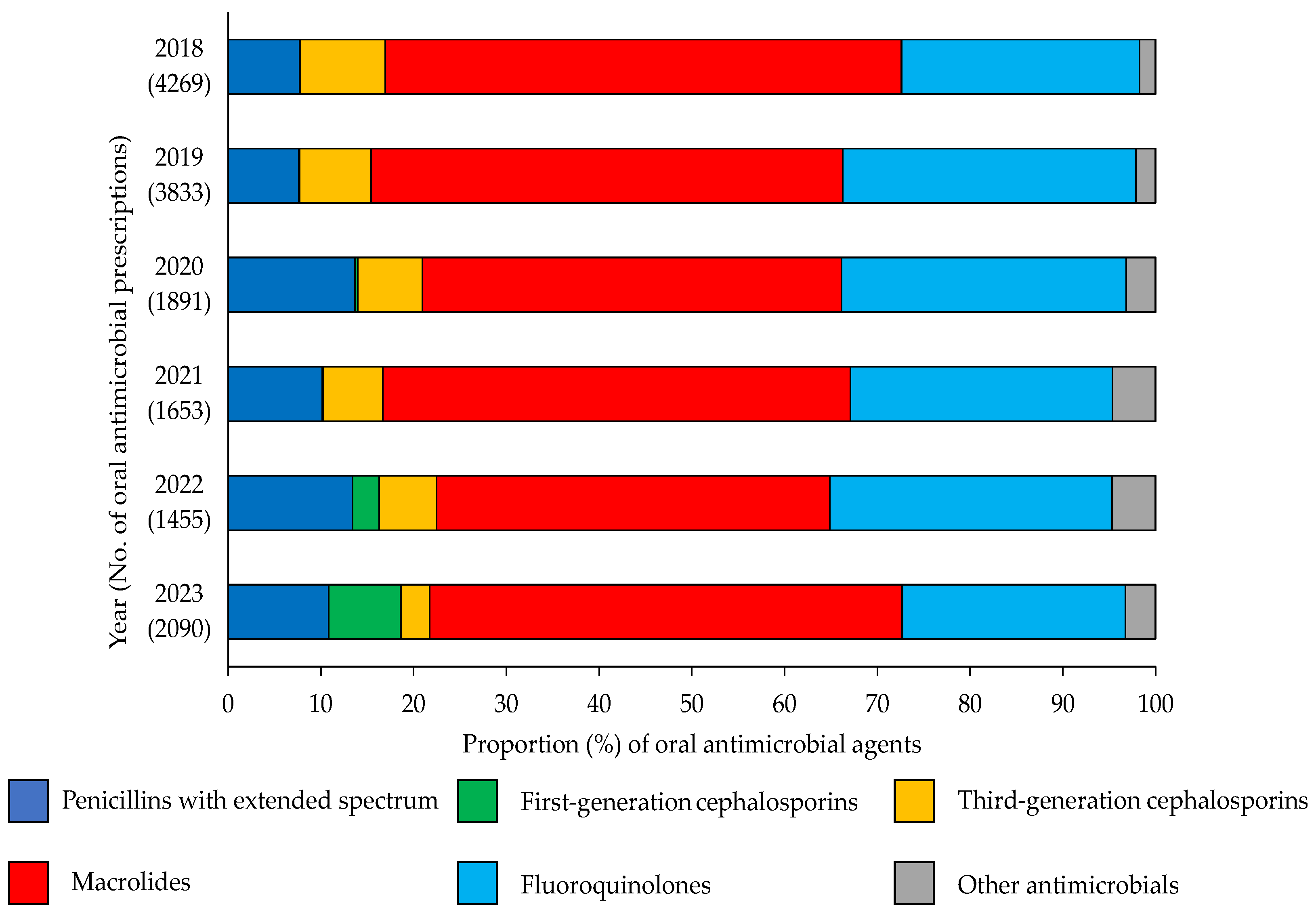

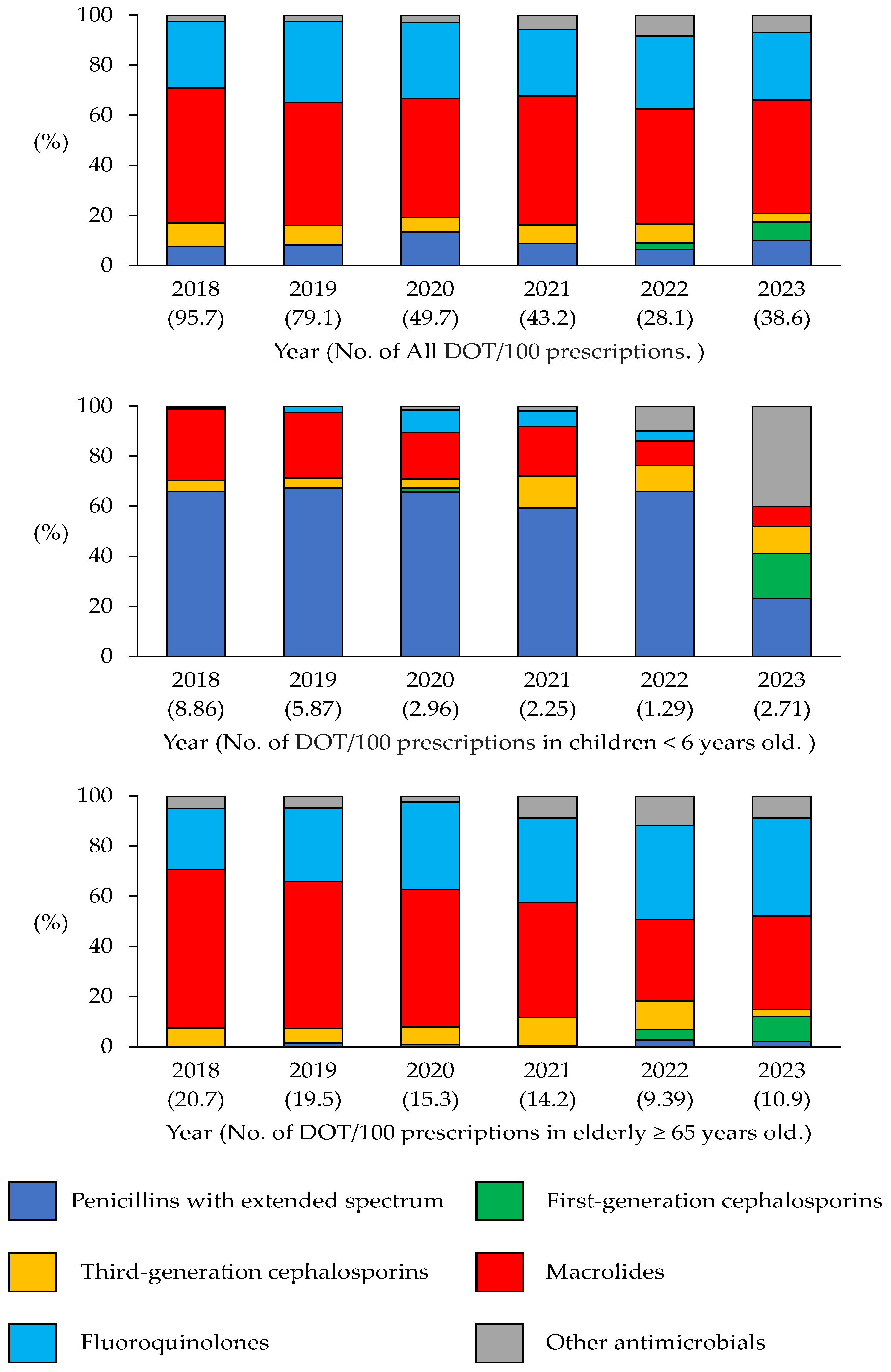

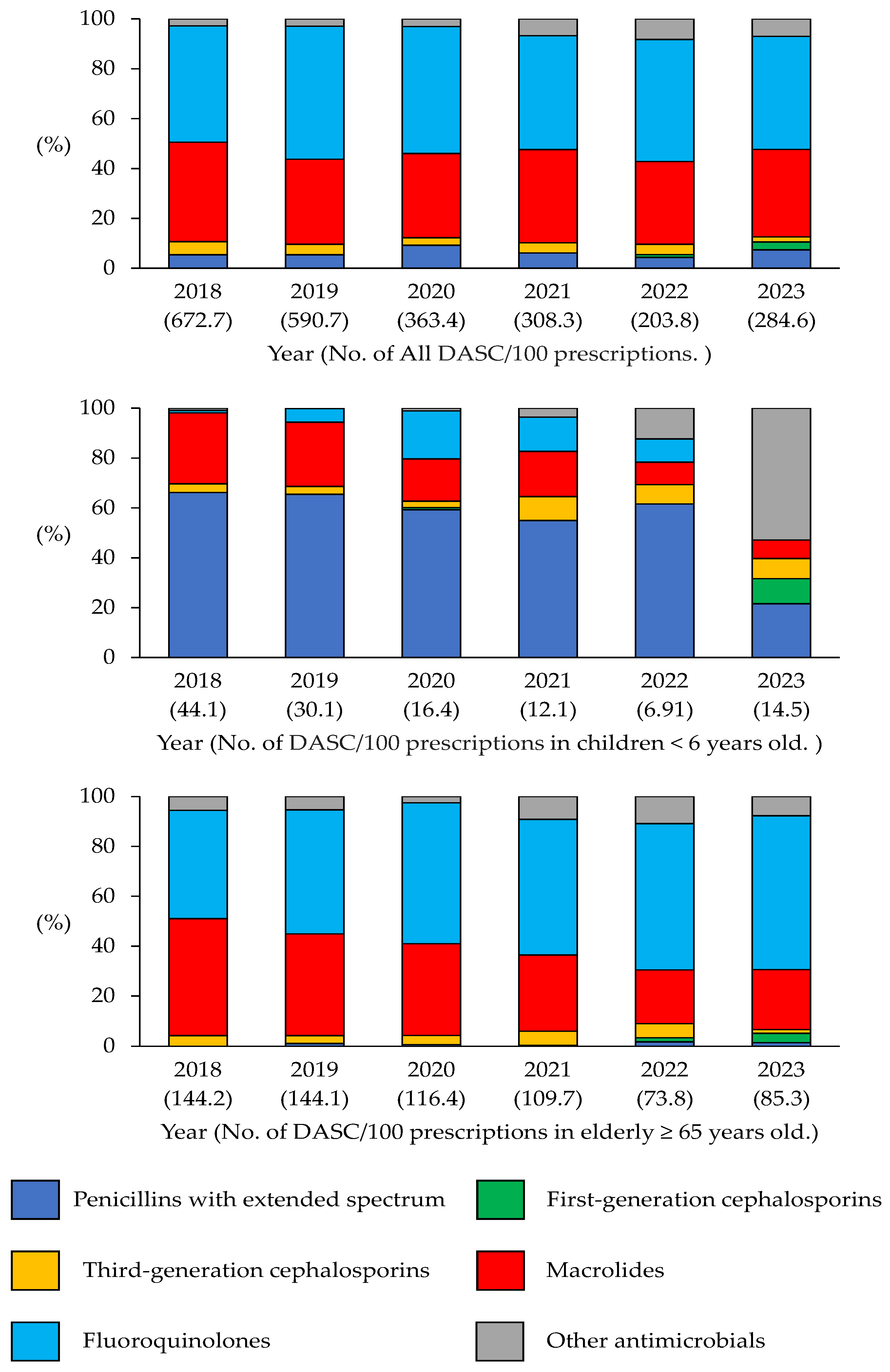

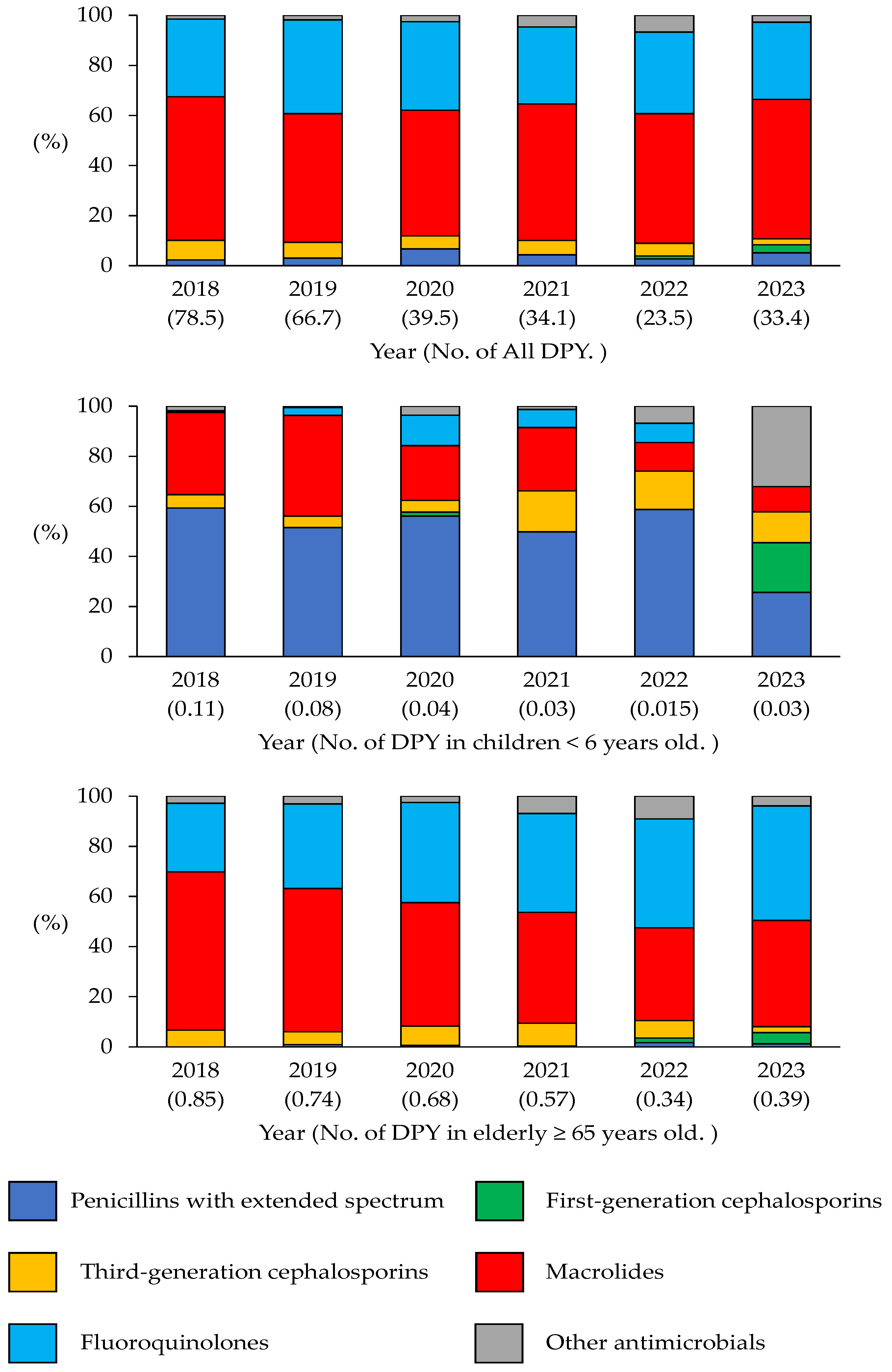

3.1. Annual Indicator Changes

3.2. Overall Trends of Antibiotic Use in a Pharmacy

3.3. Trends of Antibiotic Use in Children Aged < 6 Years

3.4. Trends of Antibiotic Use in the Elderly (≥65 Years)

3.5. Annual Trends in the DASC/DOT and Correlations

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- The Government of Japan. National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). 2023–2027. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/001096228.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Ono, A.; Koizumi, R.; Tsuzuki, S.; Asai, Y.; Ishikane, M.; Kusama, Y.; Ohmagari, N. Antimicrobial Use Fell Substantially in Japan in 2020—The COVID-19 Pandemic May Have Played a Role. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 119, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, H.; Saito, M.; Sato, J.; Goda, K.; Mitsutake, N.; Kitsuregawa, M.; Nagai, R.; Hatakeyama, S. Indications and classes of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in Japan: A descriptive study using the national database of electronic health insurance claims, 2012–2015. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, R.; Tsugawa, Y.; Ishikane, M.; Kitajima, K.; Sato, D.; Miyawaki, A. Clinic Characteristics and Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Respiratory Infections in Japan. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2440406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyawaki, A.; Ladines-Lim, J.B.; Sato, D.; Kitajima, K.; Linder, J.A.; Fischer, M.A.; Chua, K.P.; Tsugawa, Y. Association of patient, physician and visit characteristics with inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in Japanese primary care: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e002364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The AMR One Health Surveillance Committee. Nippon AMR One Health Report (NAOR) 2024. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/001477833.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Tsuzuki, S.; Koizumi, R.; Asai, Y.; Ohmagari, N. Trends in antimicrobial consumption: Long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Hayakawa, K.; Ide, S.; Ota, M.; Saito, S.; Ishikane, M.; Kusama, Y.; Matsunaga, N.; Ohmagari, N. Longitudinal trends of and factors associated with inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for non-bacterial acute respiratory tract infection in Japan: A retrospective claims database study, 2012–2017. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A.; Aoyagi, K.; Muraki, Y.; Asai, Y.; Tsuzuki, S.; Koizumi, R.; Azuma, T.; Kusama, Y.; Ohmagari, N. Trends in healthcare visits and antimicrobial prescriptions for acute infectious diarrhea in individuals aged 65 years or younger in Japan from 2013 to 2018 based on administrative claims database: A retrospective observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, H.; Kanda, N.; Yoshimoto, H.; Goda, K.; Mitsutake, N.; Hatakeyama, S. Significant reduction in antibiotic prescription rates in Japan following implementation of the national action plan on antimicrobial resistance (2016–20): A 9-year interrupted time-series analysis. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaminami, H.; Ozawa, K.; Sasai, N.; Ikeda, M.; Nemoto, O.; Baba, N.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Sawamura, D.; Shimoe, F.; Inaba, Y.; et al. Current status of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients with skin and soft tissue infections in Japan. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Mori, T.; Asakura, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Nakaminami, H. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Prescriptions in Community Pharmacies Located in Tokyo, Japan. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, Y.; Matsunaga, N.; Tsukada, A.; Kaneko, T.; Isobe, Y.; Horikoshi, Y. Chronic amoxicillin shortage led to alternative broad-spectrum antimicrobial use in pediatric clinics. J. Infect. Chemother. 2025, 31, 102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanuma, M.; Sakurai, T.; Nakaminami, H.; Tanaka, M. Evaluation of antimicrobial stewardship activities using antibiotic spectrum coverage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Arima, T.; Tashiro, R.; Yasumizu, S.; Aikou, H.; Watanabe, E.; Nakashima, T.; Nagatomo, Y.; Kakimoto, I.; Motoya, T. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship in a 126-bed community hospital with close communication between pharmacists working on post-prescription audit, ward pharmacists, and the antimicrobial stewardship team. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, K.; Hayashi, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Kondo, S.; Katanoda, T.; Okamoto, S.; Miyakawa, T.; Iwanaga, E.; Nosaka, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; et al. Antibiotic spectrum coverage scoring as a potential metric for evaluating the antimicrobial stewardship team activity: A single-center study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2024, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraki, Y.; Maeda, M.; Inose, R.; Yoshimura, K.; Onizuka, N.; Takahashi, M.; Kawakami, E.; Shikamura, Y.; Son, N.; Iwashita, M.; et al. Exploration of Trends in Antimicrobial Use and Their Determinants Based on Dispensing Information Collected from Pharmacies throughout Japan: A First Report. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakiuchi, S.; Livorsi, D.J.; Perencevich, E.N.; Diekema, D.J.; Ince, D.; Prasidthrathsint, K.; Kinn, P.; Percival, K.; Heintz, B.H.; Goto, M. Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage: A Novel Metric for Inpatient Antibiotic Consumption. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Heintz, B.H.; Livorsi, D.J.; Perencevich, E.N.; Goto, M. Tracking antimicrobial stewardship activities beyond days of therapy (DOT): Comparison of days of antibiotic spectrum coverage (DASC) and DOT at a single center. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, M.; Nakata, M.; Naito, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yamada, K.; Kinase, R.; Takuma, T.; On, R.; Tokimatsu, I. Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage Trends and Assessment in Patients with Bloodstream Infections: A Japanese University Hospital Pilot Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, N.; Ohbe, H.; Jo, T.; Matsui, H.; Fushimi, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; Yasunaga, H. Trends in inpatient antimicrobial consumption using days of therapy and days of antibiotic spectrum coverage: A nationwide claims database study in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2024, 30, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, N.; Shibata, Y.; Hirai, J.; Asai, N.; Mikamo, H. Days of antibiotic spectrum coverage (DASC) as predictors of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: A retrospective cohort study. J. Infect. Chemother. 2025, 31, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, I.; Suzuki, S.; Endo, M.; Ogawa, M.; Hasegawa, S. Feasibility and utility of the days of antibiotic spectrum coverage (DASC) in national antimicrobial use surveillance in Japan. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2025, 5, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, M.; Kakiuchi, S.; Muraki, Y. Assignments of antibiotic spectrum coverage scores of antibiotic agents approved in Japan: Utilization of the days of antibiotic spectrum coverage. J. Infect. Chemother. 2025, 31, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Pediatric Society. Available online: https://www.jpeds.or.jp/modules/news2/index.php?content_id=906 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Soucy, J.R.; Westwood, D.; Daneman, N.; MacFadden, D.R. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: Rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam Elshenawy, R.; Umaru, N.; Aslanpour, Z. WHO AWaRe classification for antibiotic stewardship: Tackling antimicrobial resistance—A descriptive study from an English NHS Foundation Trust prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1298858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, C.; McCrary, M.; Hou, R.; Abate, G. Diagnosis and Management of Pulmonary NTM with a Focus on Mycobacterium avium Complex and Mycobacterium abscessus: Challenges and Prospects. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington, K.M.; Vu, A.; Challener, D.; Rivera, C.G.; Shweta, F.N.U.; Zeuli, J.D.; Temesgen, Z. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2021, 24, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic or Metric | Median (IQR: Interquartile Range) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Number of total prescriptions received (monthly median, IQR) | 1894 (1747.3–2077.8) | 2191 (1951–2254) | 1739 (1672–1887.8) | 1884.5 (1801.5–1972.8) | 2179 (2065.3–2281) | 2326 (2185.5–2440.3) |

| Number of antimicrobial prescriptions received (monthly median, IQR) | 320 (291–391.3) | 327 (306.5–346.3) | 139.5 (128.3–173.5) | 144 (133–152.3) | 109 (99–121.3) | 172.5 (157–194) |

| DOT/100 prescriptions (median, IQR) | 91.6 (81.6–105.2) | 83.1 (73.6–85.6) | 46.2 (43.1–52.2) | 43.5 (41.4–45.7) | 28.4 (25.4–29.9) | 38.8 (32.4–43.2) |

| DASC/100 prescriptions (median, IQR) | 657.9 (567.1–720.9) | 614.3 (555.6–647) | 330.4 (304.4–376.3) | 310.2 (286.1–330.2) | 202.3 (191.2–222.6) | 265.6 (231.2–326) |

| DASC/DOT (median, IQR) | 7.0 (6.8–7.2) | 7.4 (7.8–7.5) | 7.2 (7.0–7.4) | 7.1 (6.8–7.3) | 7.3 (7.0–7.5) | 7.2 (7.0–7.4) |

| DPY (median, IQR; DDDs/100 prescriptions/year) | 74.2 (66.7–86.2) | 69.4 (62.8–71.6) | 35.0 (33.9–42.4) | 33.7 (32.6–36.0) | 24.2 (22.2–25.5) | 32.3 (29.2–38.9) |

| Indicator/Antibiotic Class | Slope | R2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOT/100 prescriptions | |||

| Total | −1.07 | 0.92 | <0.05 |

| Extended-spectrum penicillin | −0.89 | 0.94 | <0.05 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | −0.02 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| Macrolides | –0.41 | 0.89 | <0.05 |

| DASC/100 prescriptions | |||

| Total | −5.01 | 0.90 | <0.05 |

| Extended-spectrum penicillin | −5.36 | 0.93 | <0.05 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | −0.07 | 0.35 | 0.28 |

| Macrolides | −2.03 | 0.91 | <0.05 |

| DPY | |||

| Total | −0.01 | 0.90 | <0.05 |

| Extended-spectrum penicillin | −0.01 | 0.93 | <0.05 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | −0.001 | 0.35 | 0.28 |

| Macrolides | −0.004 | 0.91 | <0.05 |

| Indicator/Antibiotic Class | Slope | R2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOT/100 prescriptions | |||

| Total | −1.62 | 0.91 | <0.05 |

| First-generation cephalosporins | +0.13 | 0.67 | <0.05 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | −0.22 | 0.71 | <0.05 |

| Macrolides | −1.55 | 0.92 | <0.05 |

| Fluoroquinolones | −0.13 | 0.42 | 0.08 |

| DASC/100 prescriptions | |||

| Total | −9.98 | 0.88 | <0.05 |

| First-generation cephalosporins | +0.38 | 0.63 | <0.05 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | −0.98 | 0.75 | <0.05 |

| Macrolides | −7.94 | 0.90 | <0.05 |

| Fluoroquinolones | −2.11 | 0.56 | 0.07 |

| DPY | |||

| Total | −0.11 | 0.93 | <0.05 |

| First-generation cephalosporins | +0.003 | 0.64 | <0.05 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | −0.01 | 0.63 | <0.05 |

| Macrolides | −0.08 | 0.93 | <0.05 |

| Fluoroquinolones | −0.02 | 0.53 | 0.09 |

| Correlation Coefficient (ρ) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| DOT/100 prescriptions vs. DASC/DOT | 0.05 | 0.67 |

| DPM vs. DASC/DOT | 0.1 | 0.85 |

| DPY vs. DASC/DOT | −0.12 | 0.82 |

| Metric | Feature | Strengths | Limitations | Usefulness in Community Pharmacies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOT | Measures days of therapy | Easy to calculate, standard in hospitals | Does not reflect antimicrobial spectrum | Useful for quantifying overall antimicrobial use |

| DASC | Considers the antimicrobial spectrum | Enables spectrum-based evaluation, qualitative assessment | Limited evidence, especially in community settings; further validation is needed | Useful for evaluating the quality of antimicrobial use |

| DPM | DDDs/100 prescriptions/month | Enables monthly comparisons | Based on DDD, which may lead to discrepancies depending on the actual prescribed amount or duration; Affected by seasonal variation | Useful for monitoring short-term trends |

| DPY | DDDs/100 prescriptions/year | Enables annual comparisons, less affected by seasonality | Based on DDD, which may lead to discrepancies depending on the actual prescribed amount or duration | Useful for long-term evaluation and less affected by seasonal variation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasegawa, K.; Seyama, S.; Mori, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Nakaminami, H. Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage (DASC) and Oral Antimicrobial-Use Trends at a Community Pharmacy in Japan: A 2018–2023 Retrospective Observational Study. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14101051

Hasegawa K, Seyama S, Mori T, Matsumura Y, Nakaminami H. Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage (DASC) and Oral Antimicrobial-Use Trends at a Community Pharmacy in Japan: A 2018–2023 Retrospective Observational Study. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(10):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14101051

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasegawa, Kosuke, Shoji Seyama, Tomoko Mori, Yuriko Matsumura, and Hidemasa Nakaminami. 2025. "Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage (DASC) and Oral Antimicrobial-Use Trends at a Community Pharmacy in Japan: A 2018–2023 Retrospective Observational Study" Antibiotics 14, no. 10: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14101051

APA StyleHasegawa, K., Seyama, S., Mori, T., Matsumura, Y., & Nakaminami, H. (2025). Days of Antibiotic Spectrum Coverage (DASC) and Oral Antimicrobial-Use Trends at a Community Pharmacy in Japan: A 2018–2023 Retrospective Observational Study. Antibiotics, 14(10), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14101051