Whole-Genome Investigation of Zoonotic Transmission of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clonal Complex 398 Isolated from Pigs and Humans in Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. WGS-Based Characteristics

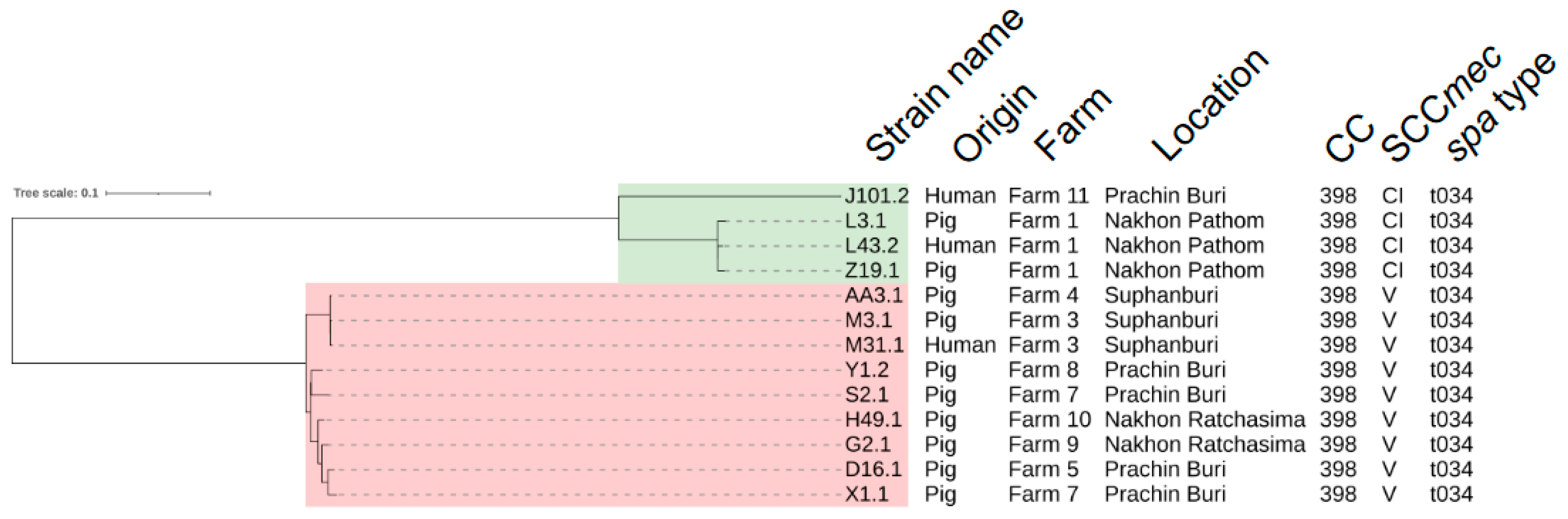

2.2. Core-Genome Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)-Based Analyses and Transmission of LA-MRSA CC398

2.3. Antimicrobial Resistance-Associated Genes and Stress Genes Profile

2.4. Virulence Gene Repertoire

2.5. Mobile Genetic Elements

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. LA-MRSA Isolates

4.2. DNA Extraction

4.3. Library Preparation, WGS and Genome Assembly

4.4. Genomic Characterization and In-Silico Identification of Antimicrobial Resistance, Stress, and Virulence Genes

4.5. Core Genome Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patchanee, P.; Tadee, P.; Arjkumpa, O.; Love, D.; Chanachai, K.; Alter, T.; Hinjoy, S.; Tharavichitkul, P. Occurrence and Characterization of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Pig Industries of Northern Thailand. J. Vet. Sci. 2014, 15, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanchaithong, P.; Perreten, V.; Am-in, N.; Lugsomya, K.; Tummaruk, P.; Prapasarakul, N. Molecular Characterization and Antimicrobial Resistance of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Pigs and Swine Workers in Central Thailand. Microbial. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, F. Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) Colonisation and Infection among Livestock Workers and Veterinarians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, A.; Loeffen, F.; Bakker, J.; Klaassen, C.; Wulf, M. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Pig Farming. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2005, 11, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Danish Health Authority. Guidance on Preventing the Spread of MRSA, 3rd ed.; The Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Lee, A.S.; de Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, T.; Verkade, E.; van Luit, M.; Landman, F.; Kluytmans, J.; Schouls, L.M. Transmission and Persistence of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Veterinarians and Their Household Members. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutters, N.T.; Bieber, C.P.; Hauck, C.; Reiner, G.; Malek, V.; Frank, U. Comparison of Livestock-Associated and Health Care–Associated MRSA—Genes, Virulence, and Resistance. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 86, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Piazuelo, D.; Lawlor, P.G. Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) Prevalence in Humans in Close Contact with Animals and Measures to Reduce on-Farm Colonisation. Ir. Vet. J. 2021, 74, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Alen, S.; Ballhausen, B.; Peters, G.; Friedrich, A.W.; Mellmann, A.; Köck, R.; Becker, K. In the Centre of an Epidemic: Fifteen Years of LA-MRSA CC398 at the University Hospital Münster. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 200, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.; Petersen, A.; Larsen, A.R.; Sieber, R.N.; Stegger, M.; Koch, A.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Price, L.B.; Skov, R.L.; ohansen, H.K.; et al. Emergence of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections in Denmark. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Assessment of the Public Health Significance of Meticillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Animals and Foods. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahreena, L.; Kunyan, Z. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Characterization, Evolution, and Epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00020-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Ali, T.; Li, J.; Song, L.; Shen, S.; Li, T.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, H. New Clues about the Global MRSA ST398: Emergence of MRSA ST398 from Pigs in Qinghai, China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 378, 109820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petinaki, E.; Papagiannitsis, C. Resistance of Staphylococci to Macrolides-Lincosamides-Streptogramins B (MLSB): Epidemiology and Mechanisms of Re-sistance. In Staphylococcus Aureus; Hemeg, H., Ozbak, H., Afrin, F., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feßler, A.T.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Schwarz, S. Mobile Lincosamide Resistance Genes in Staphylococci. Plasmid 2018, 99, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.K.; Keithly, M.E.; Sulikowski, G.A.; Armstrong, R.N. Diversity in Fosfomycin Resistance Proteins. Perspect. Sci. 2015, 4, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Hu, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, M. Prevalence of Fosfomycin Resistance and Mutations in MurA, GlpT, and UhpT in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains Isolated from Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid Samples. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naushad, S.; Naqvi, S.A.; Nobrega, D.; Luby, C.; Kastelic, J.P.; Barkema, H.W.; De Buck, J. Comprehensive Virulence Gene Profiling of Bovine Non-Aureus Staphylococci Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing Data. mSystems 2019, 4, 00098-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anukool, U.; O’Neill, C.E.; Butr-Indr, B.; Hawkey, P.M.; Gaze, W.H.; Wellington, E.M.H. Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Pigs from Thailand. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 86–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinlapasorn, S.; Lulitanond, A.; Angkititrakul, S.; Chanawong, A.; Wilailuckana, C.; Tavichakorntrakool, R.; Chindawong, K.; Seelaget, C.; Krasaesom, M.; Chartchai, S.; et al. SCCmec IX in Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Meticillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Pigs and Workers at Pig Farms in Khon Kaen, Thailand. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuno, M.; Uchiyama, M.; Nakahara, Y.; Uenoyama, K.; Fukuhara, H.; Morino, S.; Kijima, M. A Japanese Trial to Monitor Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Imported Swine during the Quarantine Period. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 14, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-K.; Nam, H.-M.; Jang, G.-C.; Lee, H.-S.; Jung, S.-C.; Kwak, H.-S. The First Detection of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in Pigs in Korea. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 155, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanomsridachchai, W. Genetic Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Pigs and Pork Meat in Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan, 2023. Volume 14717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Peng, C.; Lü, X. Diversity of SCCmec Elements in Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clinical Isolates. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Hong, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Peng, Y.; Liao, K.; Wang, H.; Zhu, F.; Zhuang, H.; et al. Exploring the Third-Generation Tetracycline Resistance of Multidrug-Resistant Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST9 across Healthcare Settings in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-P.; Li, W.-G.; Zheng, H.; Du, H.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Che, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.-M.; Lu, J.-X. Extreme Diversity and Multiple SCCmec Elements in Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus Found in the Clinic and Community in Beijing, China. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2017, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, E.M.; Paterson, G.K.; Holden, M.T.G.; Larsen, J.; Stegger, M.; Larsen, A.R.; Petersen, A.; Skov, R.L.; Christensen, J.M.; Bak Zeuthen, A.; et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Identifies Zoonotic Transmission of MRSA Isolates with the Novel MecA Homologue MecC. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanomsridachchai, W.; Changkaew, K.; Changkwanyeun, R.; Prapasawat, W.; Intarapuk, A.; Fukushima, Y.; Yamasamit, N.; Flav Kapalamula, T.; Nakajima, C.; Suthienkul, O.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Molecular Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Slaughtered Pigs and Pork in the Central Region of Thailand. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, J.L.; Smith, K.P.; Kumar, S.H.; Floyd, J.T.; Varela, M.F. LmrS Is a Multidrug Efflux Pump of the Major Facilitator Superfamily from Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 5406–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C.; Abdelbary, M.; Layer, F.; Werner, G.; Witte, W. Prevalence of the Immune Evasion Gene Cluster in Staphylococcus aureus CC398. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 177, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, G.; Bes, M.; Meugnier, H.; Enright, M.C.; Forey, F.; Liassine, N.; Wenger, A.; Kikuchi, K.; Lina, G.; Vandenesch, F.; et al. Detection of New Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clones Containing the Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin 1 Gene Responsible for Hospital- and Community-Acquired Infections in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wamel, W.J.B.; Rooijakkers, S.H.M.; Ruyken, M.; van Kessel, K.P.M.; van Strijp, J.A.G. The Innate Immune Modulators Staphylococcal Complement Inhibitor and Chemotaxis Inhibitory Protein of Staphylococcus aureus Are Located on β-Hemolysin-Converting Bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.B.; Stegger, M.; Hasman, H.; Aziz, M.; Larsen, J.; Andersen, P.S.; Pearson, T.; Waters, A.E.; Foster, J.T.; Schupp, J.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus CC398: Host Adaptation and Emergence of Methicillin Resistance in Livestock. mBio 2012, 3, 00305-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffer, A.C.; Solinga, R.M.; Cocchiaro, J.; Portoles, M.; Kiser, K.B.; Risley, A.; Randall, S.M.; Valtulina, V.; Speziale, P.; Walsh, E.; et al. Immunization with Staphylococcus aureus Clumping Factor B, a Major Determinant in Nasal Carriage, Reduces Nasal Colonization in a Murine Model. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 2145–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, M.E.; Geoghegan, J.A.; Monk, I.R.; O’Keeffe, K.M.; Walsh, E.J.; Foster, T.J.; McLoughlin, R.M. Nasal Colonisation by Staphylococcus aureus Depends upon Clumping Factor B Binding to the Squamous Epithelial Cell Envelope Protein Loricrin. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1003092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertheim, H.F.L.; Walsh, E.; Choudhurry, R.; Melles, D.C.; Boelens, H.A.M.; Miajlovic, H.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Foster, T.; van Belkum, A. Key Role for Clumping Factor B in Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Colonization of Humans. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, A.; Brégeon, F.; Mège, J.-L.; Rolain, J.-M.; Blin, O. Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Colonization: An Update on Mechanisms, Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Subsequent Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, K.A.; Mulcahy, M.E.; Towell, A.M.; Geoghegan, J.A.; McLoughlin, R.M. Clumping Factor B Is an Important Virulence Factor during Staphylococcus aureus Skin Infection and a Promising Vaccine Target. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elasri, M.O.; Thomas, J.R.; Skinner, R.A.; Blevins, J.S.; Beenken, K.E.; Nelson, C.L.; Smelter, M.S. Staphylococcus aureus Collagen Adhesin Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Osteomyelitis. Bone 2002, 30, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, J.M.; Bremell, T.; Krajewska-Pietrasik, D.; Abdelnour, A.; Tarkowski, A.; Rydén, C.; Höök, M. The Staphylococcus aureus Collagen Adhesin Is a Virulence Determinant in Experimental Septic Arthritis. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhem, M.N.; Lech, E.M.; Patti, J.M.; McDevitt, D.; Höök, M.; Jones, D.B.; Wilhelmus, K.R. The Collagen-Binding Adhesin Is a Virulence Factor in Staphylococcus aureus Keratitis. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 3776–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hienz, S.A.; Schennings, T.; Heimdahl, A.; Flock, J.-I. Collagen Binding of Staphylococcus aureus Is a Virulence Factor in Experimental Endocarditis. J. Infect. Dis. 1996, 174, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, J.L.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms: Recent Developments in Biofilm Dispersal. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Otto, M. The Staphylococcal Exopolysaccharide PIA—Biosynthesis and Role in Biofilm Formation, Colonization, and Infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3324–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, M.E.; McLoughlin, R.M. Host–Bacterial Crosstalk Determines Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Colonization. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 872–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paharik, A.E.; Horswill, A.R. The Staphylococcal Biofilm: Adhesins, Regulation, and Host Response. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 529–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, S.; Lei, T.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Dai, J.; Chen, M.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Presence and Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Co-Carrying the Multidrug Resistance Genes Cfr and Lsa(E) in Retail Food in China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 363, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendlandt, S.; Li, B.; Ma, Z.; Schwarz, S. Complete Sequence of the Multi-Resistance Plasmid PV7037 from a Porcine Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 166, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Elements (IWG-SCC). Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Mec (SCCMec): Guidelines for Reporting Novel SCCMec Elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4961–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FASTQC. A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenberg, D.; Coraor, N.; Von Kuster, G.; Taylor, J.; Nekrutenko, A.; Galaxy Team. Integrating Diverse Databases into an Unified Analysis Framework: A Galaxy Approach. Database 2011, 2011, bar011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Michelle, B.; Yue, H.; Jin, X.; Dajin, Y.; Alexandre, M.-G.; Ning, X.; Hui, L.; Shaofei, Y.; Menghan, L.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Machine Learning Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus from Multiple Heterogeneous Sources in China Reveals Common Genetic Traits of Antimicrobial Resistance. mSystems 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Cosentino, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Friis, C.; Hasman, H.; Marvig, R.L.; Jelsbak, L.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Ussery, D.W.; Aarestrup, F.M.; et al. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Total-Genome-Sequenced Bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, H.; Hasman, H.; Larsen, J.; Stegger, M.; Johannesen, T.B.; Allesøe, R.L.; Lemvigh, C.K.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Lund, O.; Larsen, A.R. SCCMecFinder, a Web-Based Tool for Typing of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Mec in Staphylococcus aureus Using Whole-Genome Sequence Data. mSphere 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, M.D.; Petersen, A.; Worning, P.; Nielsen, J.B.; Larner-Svensson, H.; Johansen, H.K.; Andersen, L.P.; Jarløv, J.O.; Boye, K.; Larsen, A.R.; et al. Comparing Whole-Genome Sequencing with Sanger Sequencing for Spa Typing of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4305–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Haft, D.H.; Prasad, A.B.; Slotta, D.J.; Tolstoy, I.; Tyson, G.H.; Zhao, S.; Hsu, C.-H.; McDermott, P.F.; et al. Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, J.; Yao, Z.; Sun, L.; Shen, Y.; Jin, Q. VFDB: A Reference Database for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (Suppl. S1), D325–D328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): A Resource Combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Snippy: Fast Bacterial Variant Calling from NGS Reads. 2015. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Croucher, N.J.; Page, A.J.; Connor, T.R.; Delaney, A.J.; Keane, J.A.; Bentley, S.D.; Parkhill, J.; Harris, S.R. Rapid Phylogenetic Analysis of Large Samples of Recombinant Bacterial Whole Genome Sequences Using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T.; Klotzl, F.; Page, A.J. Snp-Dists. Pairwise SNP Distance Matrix from a FASTA Sequence Alignment. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/snp-dists (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (ITOL) v4: Recent Updates and New Developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W256–W259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Hijmans, R. Raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. 2023. Available online: https://rspatial.org/raster (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Pebesma, E.J. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J. 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the “Tidyverse.”. 2017. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyverse (accessed on 30 July 2023).

| Strain Name | Farm | Location | ST | CC | SCCmec Type | spa Type | mec Complex Class | ccr Gene Complex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | ccrA1 | ccrB1 | ccrC1 | ||||||||

| Q10.1 | 6 | PB | 9 | 9 | IX | t337 | C2 | 1 | + | + | - |

| Y1.3 | 8 | PB | 4576 | 9 | IX | t337 | C2 | 1 | + | + | - |

| BA3.1 | 2 | RB | 9 | 9 | IX | t337 | C2 | 1 | + | + | - |

| J101.2 | 11 | PB | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | C2 | NT | + | + | + |

| L3.1 | 1 | NP | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | C2 | NT | + | + | + |

| L43.2 | 1 | NP | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | C2 | NT | + | + | + |

| Z19.1 | 1 | NP | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | C2 | NT | + | + | + |

| AA3.1 | 4 | SB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| M3.1 | 3 | SB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| M31.1 | 3 | SB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| Y1.2 | 8 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| S2.1 | 7 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| H49.1 | 10 | NR | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| G2.1 | 9 | NR | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| D16.1 | 5 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| X1.1 | 7 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | C2 | 5 | - | - | + |

| Strain Name | Q10.1 | Y1.3 | BA3.1 | J101.2 | L3.1 | L43.2 | Z19.1 | AA3.1 | M3.1 | M31.1 | Y1.2 | S2.1 | H49.1 | G2.1 | D16.1 | X1.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Pig | Pig | Pig | Human | Pig | Human | Pig | Pig | Pig | Human | Pig | Pig | Pig | Pig | Pig | Pig | |

| Farm | 6 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 7 | |

| Location | PB | PB | RB | PB | NP | NP | NP | SB | SB | SB | PB | PB | NR | NR | PB | PB | |

| ST | 9 | 4576 | 9 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | |

| CC | 9 | 9 | 9 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | |

| SCCmec type | IX | IX | IX | CI | CI | CI | CI | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | |

| spa type | t337 | t337 | t337 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | |

| AMGs | aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia | ||||||||||||||||

| aadD1 | |||||||||||||||||

| ant(6)-Ia | |||||||||||||||||

| ant(9)-Ia | |||||||||||||||||

| spw | |||||||||||||||||

| str | |||||||||||||||||

| BLs | blaPC1 | ||||||||||||||||

| blaZ | |||||||||||||||||

| mecA | |||||||||||||||||

| FQs | Mutation of gyrA S84L | ||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of parC E84G | |||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of parC S80F | |||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of parC S80Y | |||||||||||||||||

| FOS | fosB | ||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of glpT A100V | |||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of glpT F3I | |||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of murA D278E | |||||||||||||||||

| Mutation of murA E291D | |||||||||||||||||

| GPAs | vanA | ||||||||||||||||

| LINs | lnu(B) | ||||||||||||||||

| PLSA | lsa(E) | ||||||||||||||||

| vga(A) | |||||||||||||||||

| vga(A)-LC | |||||||||||||||||

| MLSB | erm(A) | ||||||||||||||||

| erm(B) | |||||||||||||||||

| erm(C) | |||||||||||||||||

| PHEs | catA | ||||||||||||||||

| fexA | |||||||||||||||||

| PhLOPSA | cfr | ||||||||||||||||

| RIF | Mutation of rpoB | ||||||||||||||||

| TCs | tet(38) | ||||||||||||||||

| tet(K) | |||||||||||||||||

| tet(L) | |||||||||||||||||

| tet(M) | |||||||||||||||||

| TMP | dfrG | ||||||||||||||||

| MATE transporter | mepA | ||||||||||||||||

| Strain Name | Q10.1 | Y1.3 | BA3.1 | J101.2 | L3.1 | L43.2 | Z19.1 | AA3.1 | M3.1 | M31.1 | Y1.2 | S2.1 | H49.1 | G2.1 | D16.1 | X1.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Pig | Pig | Pig | Human | Pig | Human | Pig | Pig | Pig | Human | Pig | Pig | Pig | Pig | Pig | Pig | |

| Farm | 6 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 7 | |

| Location | PB | PB | RB | PB | NP | NP | NP | SB | SB | SB | PB | PB | NR | NR | PB | PB | |

| ST | 9 | 4576 | 9 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | |

| CC | 9 | 9 | 9 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | 398 | |

| SCCmec type | IX | IX | IX | CI | CI | CI | CI | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | |

| spa type | t337 | t337 | t337 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | t034 | |

| Virulence genes related to adherence | clfA | ||||||||||||||||

| clfB | |||||||||||||||||

| cna | |||||||||||||||||

| ebp | |||||||||||||||||

| icaA | |||||||||||||||||

| icaB | |||||||||||||||||

| icaC | |||||||||||||||||

| icaD | |||||||||||||||||

| icaR | |||||||||||||||||

| map | |||||||||||||||||

| sdrC | |||||||||||||||||

| sdrD | |||||||||||||||||

| sdrE | |||||||||||||||||

| Virulence genes related to exoenzymes | adsA | ||||||||||||||||

| aur | |||||||||||||||||

| Coa | |||||||||||||||||

| geh | |||||||||||||||||

| hysA | |||||||||||||||||

| Lip | |||||||||||||||||

| sak * | |||||||||||||||||

| sspA | |||||||||||||||||

| sspB | |||||||||||||||||

| sspC | |||||||||||||||||

| Virulence genes related to host immune evasion | cap8A | ||||||||||||||||

| cap8B | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8C | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8D | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8E | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8F | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8G | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8L | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8M | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8N | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8O | |||||||||||||||||

| cap8P | |||||||||||||||||

| chp | |||||||||||||||||

| scn * | |||||||||||||||||

| sbi | |||||||||||||||||

| spa | |||||||||||||||||

| Virulence genes related to iron uptake and metabolism | isdA | ||||||||||||||||

| isdB | |||||||||||||||||

| isdC | |||||||||||||||||

| isdD | |||||||||||||||||

| isdE | |||||||||||||||||

| isdF | |||||||||||||||||

| isdG | |||||||||||||||||

| srtB | |||||||||||||||||

| Virulence genes related to toxins and type IV secretion | esaA | ||||||||||||||||

| esaB | |||||||||||||||||

| essA | |||||||||||||||||

| essB | |||||||||||||||||

| essC | |||||||||||||||||

| esxA | |||||||||||||||||

| esxB | |||||||||||||||||

| esxC | |||||||||||||||||

| hla | |||||||||||||||||

| hlb | |||||||||||||||||

| hld | |||||||||||||||||

| hlgA | |||||||||||||||||

| hlgB | |||||||||||||||||

| hlgC | |||||||||||||||||

| lukF-PV | |||||||||||||||||

| lukS-PV | |||||||||||||||||

| sea * | |||||||||||||||||

| sep * | |||||||||||||||||

| sei * | |||||||||||||||||

| sel26* | |||||||||||||||||

| sel27 * | |||||||||||||||||

| sel28 * | |||||||||||||||||

| selx * | |||||||||||||||||

| sem * | |||||||||||||||||

| sen * | |||||||||||||||||

| seo * | |||||||||||||||||

| seu * | |||||||||||||||||

| sey * | |||||||||||||||||

| tsst-1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Strain Name | Origin | Farm | Location | ST | CC | SCCmec Type | spa Type | ARG-Associated Plasmid Replicon and Transposon | Insertion Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q10.1 | Pig | 6 | PB | 9 | 9 | IX | t337 | rep5d-vga(A)-LC | - |

| rep7a-str-cat(pC221) | |||||||||

| rep13-qacG | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-mecA-tet(M) | |||||||||

| Y1.3 | Pig | 8 | PB | 4576 | 9 | IX | t337 | rep5d-vga(A)-LC | - |

| rep7a-str | |||||||||

| rep13-qacG | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-mecA-tet(M) | |||||||||

| BA3.1 | Pig | 2 | RB | 9 | 9 | IX | t337 | rep7a-str | - |

| rep10b-vga(A)-LC | |||||||||

| repUS18-aadD-erm(B)-tet(L) | |||||||||

| repUS43-mecA-tet(M) | |||||||||

| Tn558 | |||||||||

| J101.2 | Human | 11 | PB | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | lS256 |

| rep22-aadD-ant(6)-la-blaZ *-lnu(B)-lsa(E) | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M) | |||||||||

| Tn551-erm(B) | |||||||||

| Tn554-ant(9)-la-erm(A) | |||||||||

| L3.1 | Pig | 1 | NP | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep22-aadD | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M) | |||||||||

| Tn551-erm(B) | |||||||||

| Tn554-ant(9)-la-erm(A) | |||||||||

| L43.2 | Human | 1 | NP | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | lSSau8 |

| rep22-aadD | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M) | |||||||||

| Tn551-erm(B) | |||||||||

| Tn554-ant(9)-la-erm(A) | |||||||||

| Z19.1 | Pig | 1 | NP | 398 | 398 | CI | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep22-aadD | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M) | |||||||||

| Tn551-erm(B) | |||||||||

| Tn554-ant(9)-la-erm(A) | |||||||||

| AA3.1 | Pig | 4 | SB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| M3.1 | Pig | 3 | SB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a | - |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep19b | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| M31.1 | Human | 3 | SB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| Y1.2 | Pig | 8 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep10 | |||||||||

| rep19b | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| S2.1 | Pig | 7 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep13-qacG | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| H49.1 | Pig | 10 | NR | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| G2.1 | Pig | 9 | NR | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | - |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| D16.1 | Pig | 5 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | lSSau8 |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep13 | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| rep21 | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 | |||||||||

| X1.1 | Pig | 7 | PB | 398 | 398 | V | t034 | rep7a-tet(K) | lSSau8 |

| rep10-erm(C) | |||||||||

| rep19b-blaZ | |||||||||

| repUS43-tet(M)-Tn6009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Narongpun, P.; Chanchaithong, P.; Yamagishi, J.; Thapa, J.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y. Whole-Genome Investigation of Zoonotic Transmission of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clonal Complex 398 Isolated from Pigs and Humans in Thailand. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121745

Narongpun P, Chanchaithong P, Yamagishi J, Thapa J, Nakajima C, Suzuki Y. Whole-Genome Investigation of Zoonotic Transmission of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clonal Complex 398 Isolated from Pigs and Humans in Thailand. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(12):1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121745

Chicago/Turabian StyleNarongpun, Pawarut, Pattrarat Chanchaithong, Junya Yamagishi, Jeewan Thapa, Chie Nakajima, and Yasuhiko Suzuki. 2023. "Whole-Genome Investigation of Zoonotic Transmission of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clonal Complex 398 Isolated from Pigs and Humans in Thailand" Antibiotics 12, no. 12: 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121745

APA StyleNarongpun, P., Chanchaithong, P., Yamagishi, J., Thapa, J., Nakajima, C., & Suzuki, Y. (2023). Whole-Genome Investigation of Zoonotic Transmission of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clonal Complex 398 Isolated from Pigs and Humans in Thailand. Antibiotics, 12(12), 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121745