Magnetic Europium Ion-Based Fluorescence Sensing Probes for the Detection of Tetracyclines in Complex Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Instrumentation

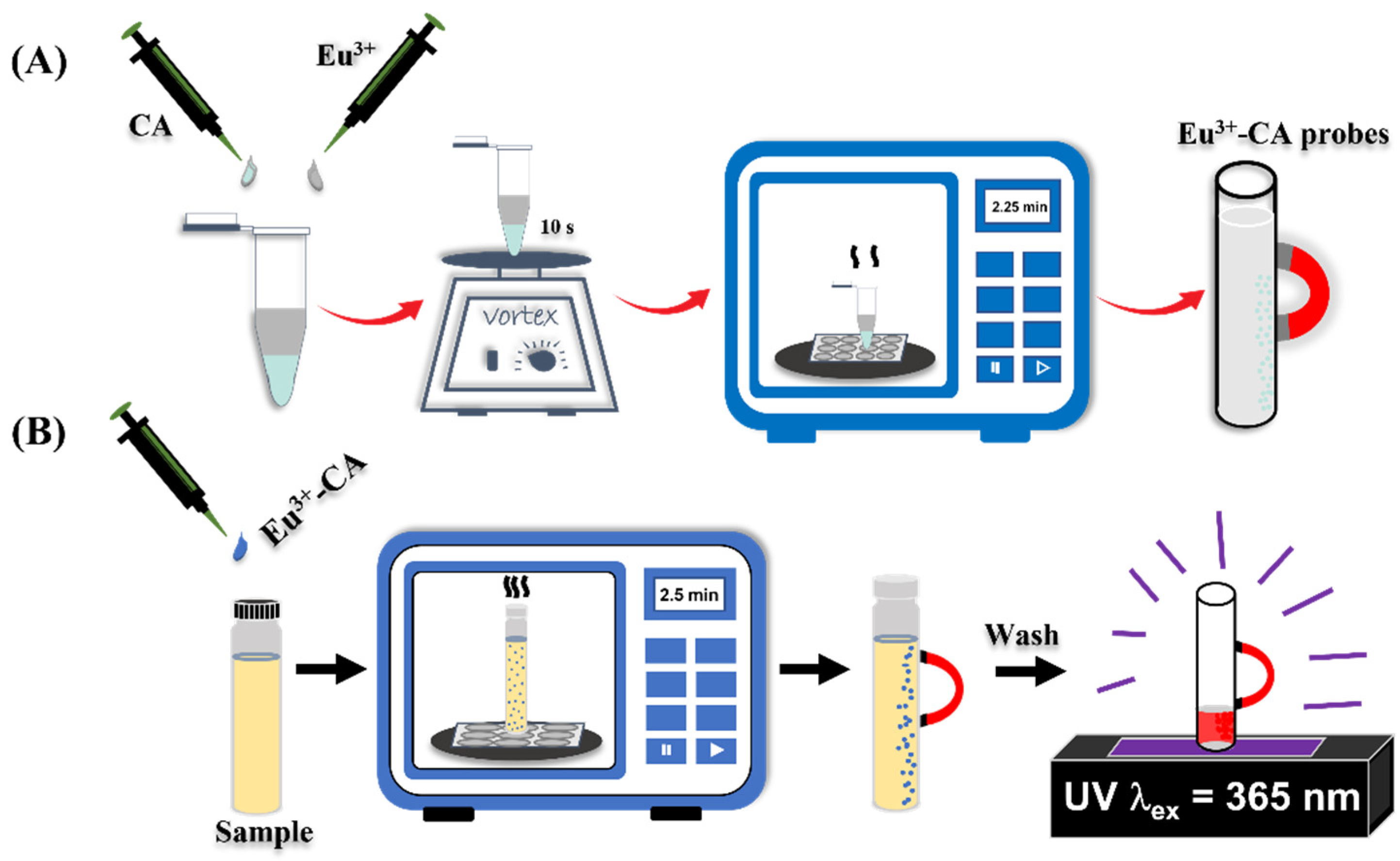

2.3. Preparation and Optimization of the Magnetic Probes

2.4. Using the Eu3+-CA Conjugates as Magnetic Probes Against TC

2.5. Effects of Interference Species

2.6. Examination of Selectivity

2.7. Preparation of the Simulated Real Samples

3. Results and Discussion

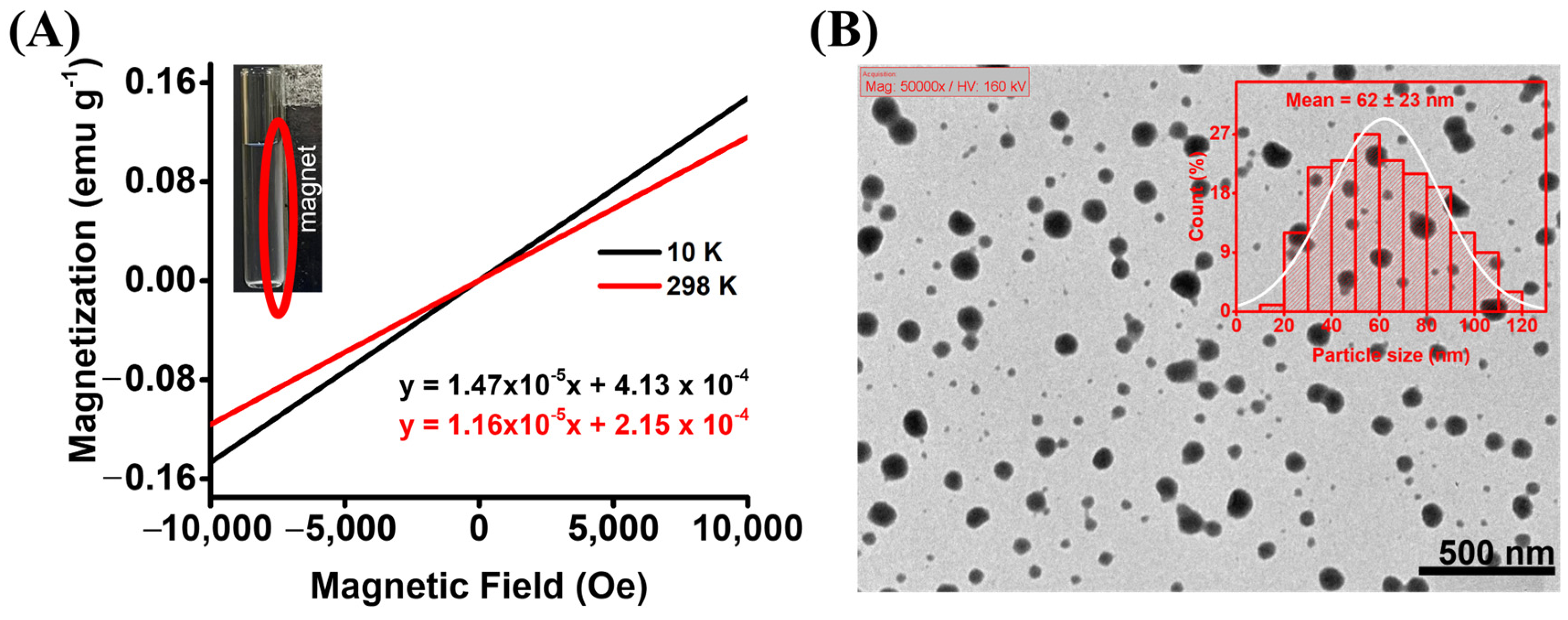

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Eu3+-CA Conjugates

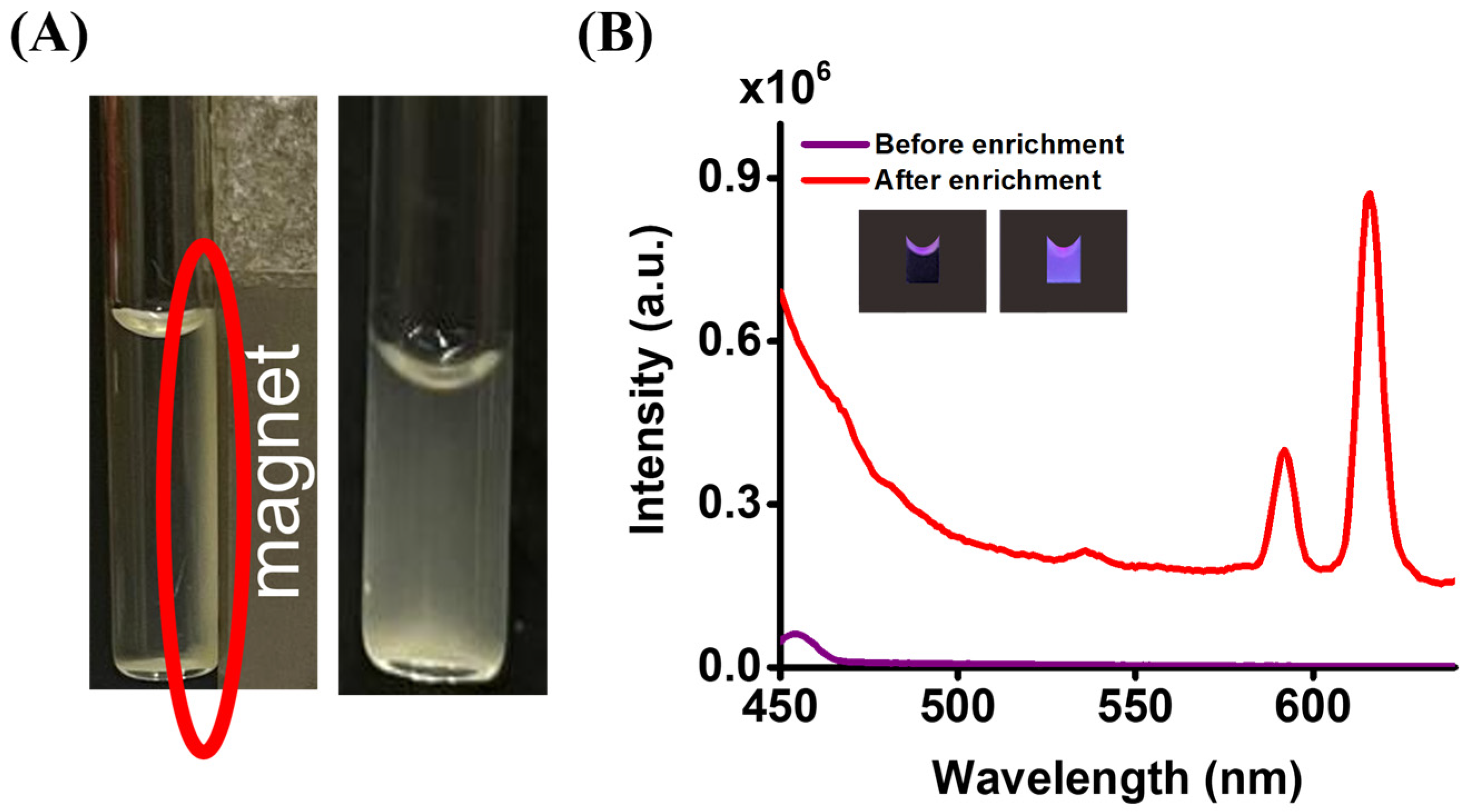

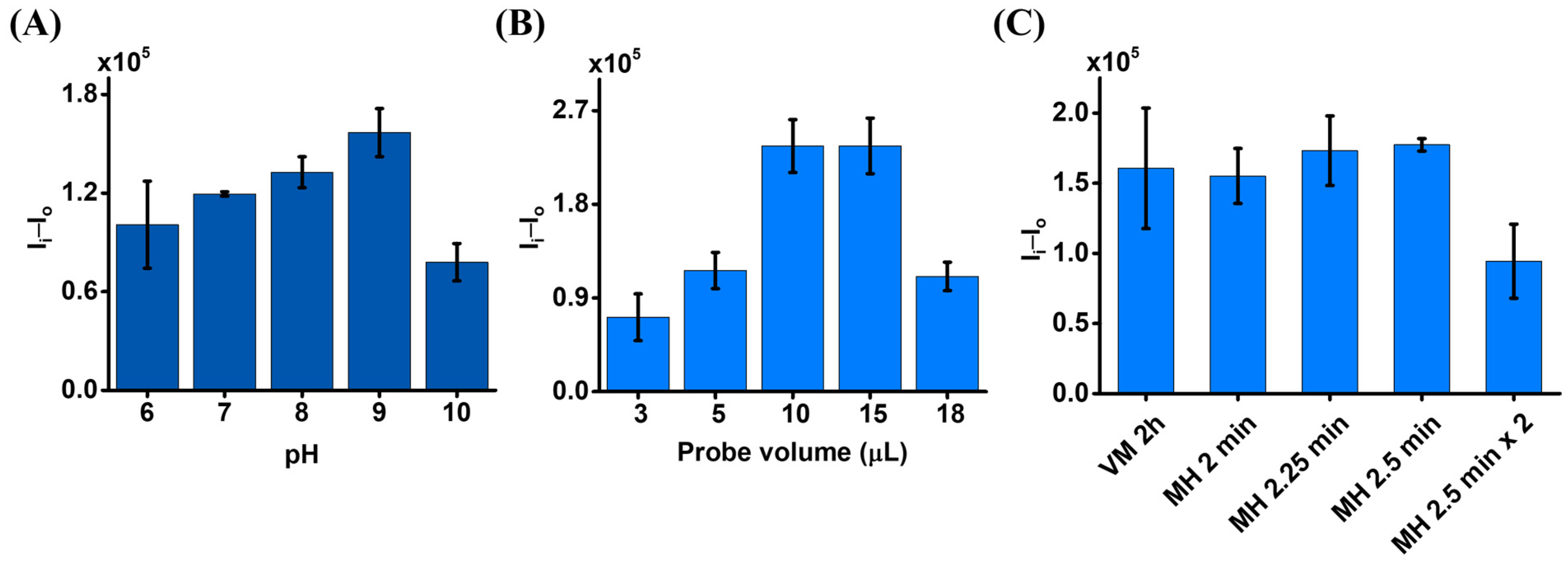

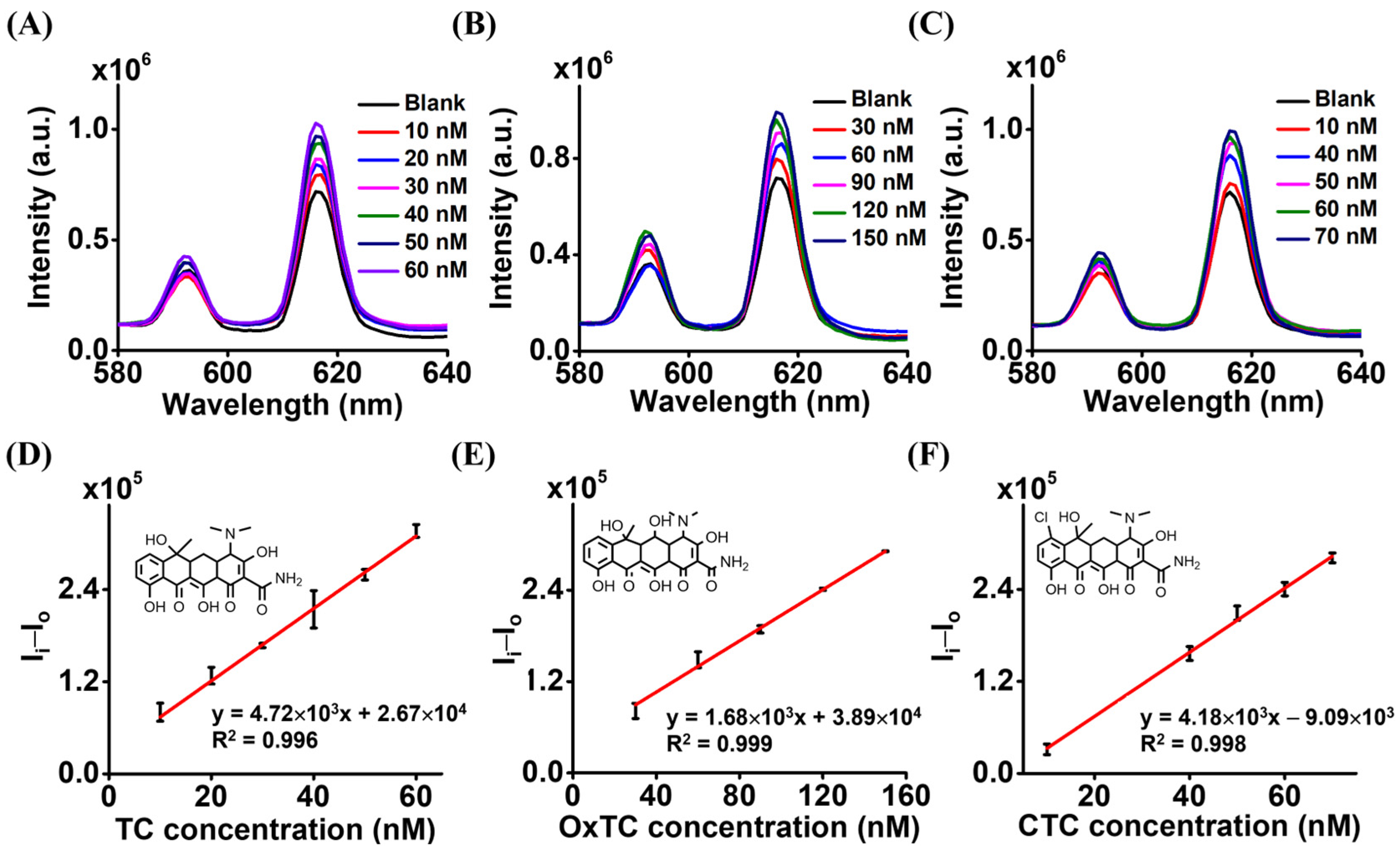

3.2. Using Magnetic Eu3+-CA Conjugates as the Sensing Probe

3.3. Evaluation of Precision and Accuracy of the Developed Method

3.4. Examination of Interference Effects and Selectivity

3.5. Analysis of Simulated Real Samples

3.6. Blind Sample Test

3.7. Comparison of the Developed Method with the Existing Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stocker, M.; Klingenberg, C.; Navér, L.; Nordberg, V.; Berardi, A.; El Helou, S.; Fusch, G.; Bliss, J.M.; Lehnick, D.; Dimopoulou, V. Less is more: Antibiotics at the beginning of life. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Xu, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Jones, D.L.; Zou, J. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils: A systematic analysis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, J.; Yao, Z.; Li, M. A review on the alternatives to antibiotics and the treatment of antibiotic pollution: Current development and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Zhang, S.; Hou, J.; Cheng, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q. Contamination distribution and non-biological removal pathways of typical tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Xie, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Guo, Z.; Xu, B.B.; Gu, H. Magnetic field facilitated electrocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in wastewater by magnetic porous carbonized phthalonitrile resin. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 340, 123225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, H. Antibiotic resistance in developing countries: Emerging threats and policy responses. Public Health Chall. 2025, 4, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, J.; Piosik, M.; Ginter-Kramarczyk, D.; Zembrzuska, J.; Kruszelnicka, I. Tetracyclines contamination in European aquatic environments: A comprehensive review of occurrence, fate, and removal techniques. Chemosphere 2024, 353, 141519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uma, G.; Ashenef, A. Determination of some antibiotic residues (tetracycline, oxytetracycline and penicillin-G) in beef sold for public consumption at Dukem and Bishoftu (Debre Zeyit) towns, central Ethiopia by LC/MS/MS. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2242633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zergiebel, S.; Ueberschaar, N.; Seeling, A. Development and optimization of an ultra-fast microextraction followed by HPLC-UV of tetracycline residues in milk products. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Tong, H.Y.K.; Chong, W.H.; Li, Z.; Tam, P.K.H.; Baptista-Hon, D.T.; Monteiro, O. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of long-term antibiotic use on cognitive outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Awasthi, M.K.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Tuo, Y. Veterinary tetracycline residues: Environmental occurrence, ecotoxicity, and degradation mechanism. Environ. Res. 2025, 266, 120417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Xie, Q.; Yang, M.; Wu, N.; Lian, Y.; Fang, C. Degradation of leachate and high concentration emerging pollutant tetracycline through electro oxidation. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 159, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Commission Regulation. Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/1229, Supplementing Regulation (EU) 2019/4 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing Specific Maximum Levels of Cross-Contamination of Antimicrobial Active Substances in Non-Target Feed and Methods of Analysis for These Substances in Feed, No. C/2024/954. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1229&qid=1759891917733 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Codex Alimentarius International Food Standards. Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) and Risk Management Recommendations (RMRs) for Residues of Veterinary Drugs in Foods; CXM2-2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/maximum-residue-limits/en/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Yue, X.; Fu, L.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y. Fluorescent and smartphone imaging detection of tetracycline residues based on luminescent europium ion-functionalized the regular octahedral UiO-66-NH2. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilnit, T.; Jeenno, J.; Supharoek, S.-a.; Vichapong, J.; Siriangkhawut, W.; Ponhong, K. Synergy of iron-natural phenolic microparticles and hydrophobic ionic liquid for enrichment of tetracycline residues in honey prior to HPLC-UV detection. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhonchai, N.; Prompila, N.; Ponhong, K.; Siriangkhawut, W.; Vichapong, J.; Supharoek, S.-a. Green hairy basil seed mucilage biosorbent for dispersive solid phase extraction enrichment of tetracyclines in bovine milk samples followed by HPLC analysis. Talanta 2024, 271, 125645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.; Kelani, K.M.; Hegazy, M.A.; Nadim, A.H.; Tantawy, M.A. A probe of new molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction coupled with HPLC-DAD and atomic absorption spectrophotometry for quantification of tetracycline HCl, metronidazole and bismuth subcitrate in combination with their official impurities: Application in dosage form and human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B 2024, 1234, 124032. [Google Scholar]

- Khatami, A.; Moghaddam, A.D.; Talatappeh, H.D.; Mohammadimehr, M. Simultaneous extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and tetracycline antibiotics from honey samples using dispersive solid phase extraction combined with dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction before their determination with HPLC-DAD. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 131, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golrizkhatami, F.; Taghavi, L.; Nasseh, N.; Panahi, H.A. Synthesis of novel MnFe2O4/BiOI green nanocomposite and its application to photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride:(LC-MS analyses, mechanism, reusability, kinetic, radical agents, mineralization, process capability, and purification of actual pharmaceutical wastewater). J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2023, 444, 114989. [Google Scholar]

- Gab-Allah, M.A.; Lijalem, Y.G.; Yu, H.; Lim, D.K.; Ahn, S.; Choi, K.; Kim, B. Accurate determination of four tetracycline residues in chicken meat by isotope dilution-liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1691, 463818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Souza, M.J.; Martin-Jimenez, T.; Abouelkhair, M.A.; Kania, S.A.; Okafor, C.C. Tetracycline, sulfonamide, and erythromycin residues in beef, eggs, and honey sold as “antibiotic-free” products in East Tennessee (USA) farmers’ markets. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Peng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. A bioluminescence method based on NLuc-TetR for the detection of nine tetracyclines in milk. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 109931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Z. Simultaneous separation of 12 different classes of antibiotics under the condition of complete protonation by capillary electrophoresis-coupled contactless conductivity detection. Anal. Methods 2022, 14, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akono, A.R.Z.; Blaise, N.; Valery, H.G. Preparation of a carbon paste electrode with active materials for the detection of tetracycline. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, W.; Zhan, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Aptamer tuned nanozyme activity of nickel-metal–organic framework for sensitive electrochemical aptasensing of tetracycline residue. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Halima, H.; Baraket, A.; Vinas, C.; Zine, N.; Bausells, J.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Teixidor, F.; Errachid, A. Selective antibody-free sensing membranes for picogram tetracycline detection. Biosensors 2022, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.M.; Kelani, K.M.; Hegazy, M.A.; Tantawy, M.A. Molecular imprinted polymer-based potentiometric approach for the assay of the co-formulated tetracycline HCl, metronidazole and bismuth subcitrate in capsules and spiked human plasma. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1278, 341707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-S.; Liang, H.-W.; Wu, C.-T.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Song, Y.-T.; Gong, W.; Li, J. Ratiometric fluorescence sensor for tetracycline detection based on two fluorophores derived from Partridge tea. Mikrochim. Acta 2023, 190, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Wang, W.; Zheng, G.; Dong, W.; Cheng, R.; Shang, X.; Xu, Y.; Fang, W.; Wang, H.; Jiang, C.; et al. Two birds with one stone: Ratiometric sensing platform overcoming cross-interference for multiple-scenario detection and accurate discrimination of tetracycline analogs. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 132016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Lv, C.; Pang, J.; Yang, Z.; Sha, H. Establishment of an indirect ELISA detection method for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus NSP4. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1549008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, A.; Liang, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Chen, W. A novel cell-and virus-free SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody ELISA based on site-specific labeling technology. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 18437–18444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.-M.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.-T.; Liu, Q.-H.; Liu, Y.-L.; Li, S.-J.; Fu, Y.; Ye, F. A novel fluorescence platform for specific detection of tetracycline antibiotics based on [MQDA-Eu3+] system. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Fu, Q.; Li, Y.; Yan, C.; Xiao, D.; Ju, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, H.; Ai, S. Zinc-doped carbon quantum dots-based ratiometric fluorescence probe for rapid, specific, and visual determination of tetracycline hydrochloride. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Hua, Y.; Huang, D.; Guo, H.; Qiu, X. Ratiometric fluorescent probes based on carbon dots and europium for rapid detection of tetracycline. Opt. Mater. 2024, 150, 115227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tian, D.; Phan, A.; Seididamyeh, M.; Alanazi, M.; Ping Xu, Z.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Zhang, R. Luminescent sensors for residual antibiotics detection in food: Recent advances and perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 498, 215455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yu, L.; Bai, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Tian, Y.; Qin, S.; Yang, Y. Two birds with one stone: A universal design and application of signal-on labeled fluorescent/electrochemical dual-signal mode biosensor for the detection of tetracycline residues in tap water, milk and chicken. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 136904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, A.; Yabalak, E.; Nural, Y. Tetracycline Chemosensors: Materials, Mechanisms, and Applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 2026, 1044, 123942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawalha, S.; Silvestri, A.; Criado, A.; Bettini, S.; Prato, M.; Valli, L. Tailoring the sensing abilities of carbon nanodots obtained from olive solid wastes. Carbon 2020, 167, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopalan, P.; Vidya, N. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of carbon dots derived from wild lemon (Citrus pennivesiculata) leaves as a fluorescent probe for tetracycline sensing in water. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 286, 122024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Wang, S. Carbon dots-based fluorescent molecularly imprinted photonic crystal hydrogel strip: Portable and efficient strategy for selective detection of tetracycline in foods of animal origin. Food Chem. 2024, 433, 137407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z. Highly sensitive ratiometric fluorescence detection of tetracycline residues in food samples based on Eu/Zr-MOF. Food Chem. 2024, 436, 137717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ji, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xu, X.; Bao, L.; Cui, M.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z. A smart Zn-MOF-based ratiometric fluorescence sensor for accurate distinguish and optosmart sensing of different types of tetracyclines. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 640, 158442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezerlou, A.; Tavassoli, M.; Sani, M.A.; Ghasempour, Z.; Ehsani, A.; Khalilzadeh, B. Rapid and sensitive detection of tetracycline residue in food samples using Cr (III)-MOF fluorescent sensor. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, X.; Liu, J.; Xiong, Z.; Zhao, L. Facile construction of a bifunctional Eu-MOF for selective fluorescence sensing and visible light photocatalysis of tetracycline. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1003, 175730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhan, H.; Zhai, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, W.; Zou, Y.; Xu, K. An enzyme-free and label-free ratiometric fluorescence signal amplification biosensor based on DNA-silver nanoclusters and catalytic hairpin assembly for tetracycline detection. Sens. Actuators B 2024, 404, 135216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaelpourfarkhani, M.; Hazeri, Y.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M. A novel turn-off Tb3+/ssDNA complex-based time-resolved fluorescent aptasensor for oxytetracycline detection using the powerful sensitizing property of the modified complementary strand on Tb3+ emission. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, N.; Xia, X. Study of dual binding specificity of aptamer to ochratoxin A and norfloxacin and the development of fluorescent aptasensor in milk detection. Talanta 2024, 273, 125935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mei, Q.; Tao, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhao, M.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. A smartphone-integrated ratiometric fluorescence sensing platform for visual and quantitative point-of-care testing of tetracycline. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 148, 111791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.-L.; Chen, Y.-C. Using magnetic ions to probe and induce magnetism of pyrophosphates, bacteria, and mammalian cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 30837–30843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Yang, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-C. Using magnetic micelles combined with carbon fiber ionization mass spectrometry for screening of trace triazine herbicides from aqueous samples. Molecules 2024, 29, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.-L.; Huang, D.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. Using gadolinium ions as affinity probes to selectively enrich and magnetically isolate bacteria from complex samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1113, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.-C.; Chiu, C.-P.; Chen, Y.-C. Using lanthanide ions as magnetic and sensing probes for the detection of tetracycline from complex samples. J Food Drug Anal. 2023, 31, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.-J.; Zhan, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. A facile switch-on fluorescence sensing method for detecting phosphates from complex aqueous samples. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 380, 133298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannatin, M.; Yang, T.-L.; Su, Y.-Y.; Mai, R.-T.; Chen, Y.-C. Europium ion-based magnetic-trapping and fluorescence-sensing method for detection of pathogenic bacteria. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 5669–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wei, S.; Xie, Y.; Su, K.; Yin, X.; Song, X.; Hu, K.; Sun, G.; Liu, Y. Ratiometric fluorescence sensor based on chiral europium-doped carbon dots for specific and portable detection of tetracycline. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 423, 136753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. MALDI MS analysis of oligonucleotides: Desalting by functional magnetite beads using microwave-assisted extraction. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 8061–8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuong, C.-L.; Yu, T.-J.; Chen, Y.-C. Microwave-assisted sensing of tetracycline using europium-sensitized luminescence fibers as probes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Chen, W.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. Iron oxide/tantalum oxide core–shell magnetic nanoparticle-based microwave-assisted extraction for phosphopeptide enrichment from complex samples for MALDI MS analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 2129–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnadjevic, B.; Jovanovic, J. The effect of microwave heating on the isothermal kinetics of chemicals reaction and physicochemical processes. In Advances in Induction and Microwave Heating of Mineral and Organic Materials; IntechOpen: Hamilton, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 391–422. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, N.; Sun, L.; Hu, M.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Jia, L. A sensitive visual intelligent fluorescence detection platform for tetracycline detection based on silicon quantum dots. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Han, D.-M. Liposome-encapsulated aggregation-induced emission fluorogen assisted with portable smartphone for dynamically on-site imaging of residual tetra-cycline. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 350, 130871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Fan, C.; Pu, S. Luminol-Eu-based ratiometric fluorescence probe for highly selective and visual determination of tetracycline. Talanta 2021, 234, 122612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, R.; Feng, X. A smartphone-assisted paper-based ratio fluorescent probe for the rapid and on-site detection of tetracycline in food samples. Talanta 2023, 265, 124874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, B.T.; Nghia, N.N.; Lee, Y.-I. Highly sensitive colorimetric paper-based analytical device for the determination of tetracycline using green fluorescent carbon nitride nanoparticles. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, G. Rational design of MoS2 QDs and Eu3+ as a ratiometric fluorescent probe for point-of-care visual quantitative detection of tetracycline via smartphone-based portable platform. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1198, 339572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Shen, X.; Jia, L.; Zhou, T.; Ma, T.; Xu, Z.; Cao, J.; Ge, Z.; Bi, N.; Zhu, T. A novel visual ratiometric fluorescent sensing platform for highly sensitive visual detection of tetracyclines by a lanthanide-functionalized palygorskite nanomaterial. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 342, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Guo, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, T. A ratiometric fluorescent nano-probe for rapid and specific detection of tetracycline residues based on a dye-doped functionalized nanoscaled metal–organic framework. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Fan, Y.Z.; Qing, M.; Liu, S.G.; Yang, Y.Z.; Li, N.B.; Luo, H.Q. Smartphones and test paper-assisted ratiometric fluorescent sensors for semi-quantitative and visual assay of tetracycline based on the target-induced synergistic effect of antenna effect and inner filter effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 47099–47107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ti, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, D.; Wu, L.; Yuan, L.; He, Y. A ratiometric nanoprobe based on carboxylated graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets and Eu3+ for the detection of tetracyclines. Analyst 2021, 146, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Chen, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Bi, N.; Gou, J.; Zhao, T. A stick-like intelligent multicolor nano-sensor for the detection of tetracycline: The integration of nano-clay and carbon dots. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Bi, N.; Bie, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, J. Ultrasensitive and visual detection of tetracycline based on dual-recognition units constructed multicolor fluorescent nano-probe. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Guo, S.; Jia, L.; Zhu, T.; Chen, X.; Zhao, T. A smartphone-integrated method for visual detection of tetracycline. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 127741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Su, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Gagrani, N.; Li, Z.; Lockrey, M.; Li, L.; Aharonovich, I.; Lu, Y.; et al. High-Speed Multiwavelength InGaAs/InP Quantum Well Nanowire Array Micro-LEDs for Next Generation Optical Communications. Opto-Electron. Sci. 2023, 2, 230003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, M.; Cheng, S.; Wang, J.; Yi, Y.; Li, B.; Tang, C.; Gao, F. Bilayer Graphene Metasurface with Dynamically Reconfigurable Terahertz Perfect Absorption. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2025, 80, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jannatin, M.; Chen, Y.-C. Magnetic Europium Ion-Based Fluorescence Sensing Probes for the Detection of Tetracyclines in Complex Samples. Biosensors 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010029

Jannatin M, Chen Y-C. Magnetic Europium Ion-Based Fluorescence Sensing Probes for the Detection of Tetracyclines in Complex Samples. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleJannatin, Miftakhul, and Yu-Chie Chen. 2026. "Magnetic Europium Ion-Based Fluorescence Sensing Probes for the Detection of Tetracyclines in Complex Samples" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010029

APA StyleJannatin, M., & Chen, Y.-C. (2026). Magnetic Europium Ion-Based Fluorescence Sensing Probes for the Detection of Tetracyclines in Complex Samples. Biosensors, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010029