Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of K-562 Leukemia Cells Using TiO2-Modified Graphite Nanostructured Electrode

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Preparation of the GO/HOPG Electrode

2.3. Preparation of Modified TiO2

2.4. Preparation of Electrode TiO2-m/GO/HOPG

2.5. Cell Culture Medium

2.6. Cell Culture

2.7. Cell Fixation on TGO360 Plates

2.8. DAPI Staining

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM-EDS)

2.10. Assembly of the Electrochemical Cell Biosensor

2.11. Electrochemical Tests

3. Results

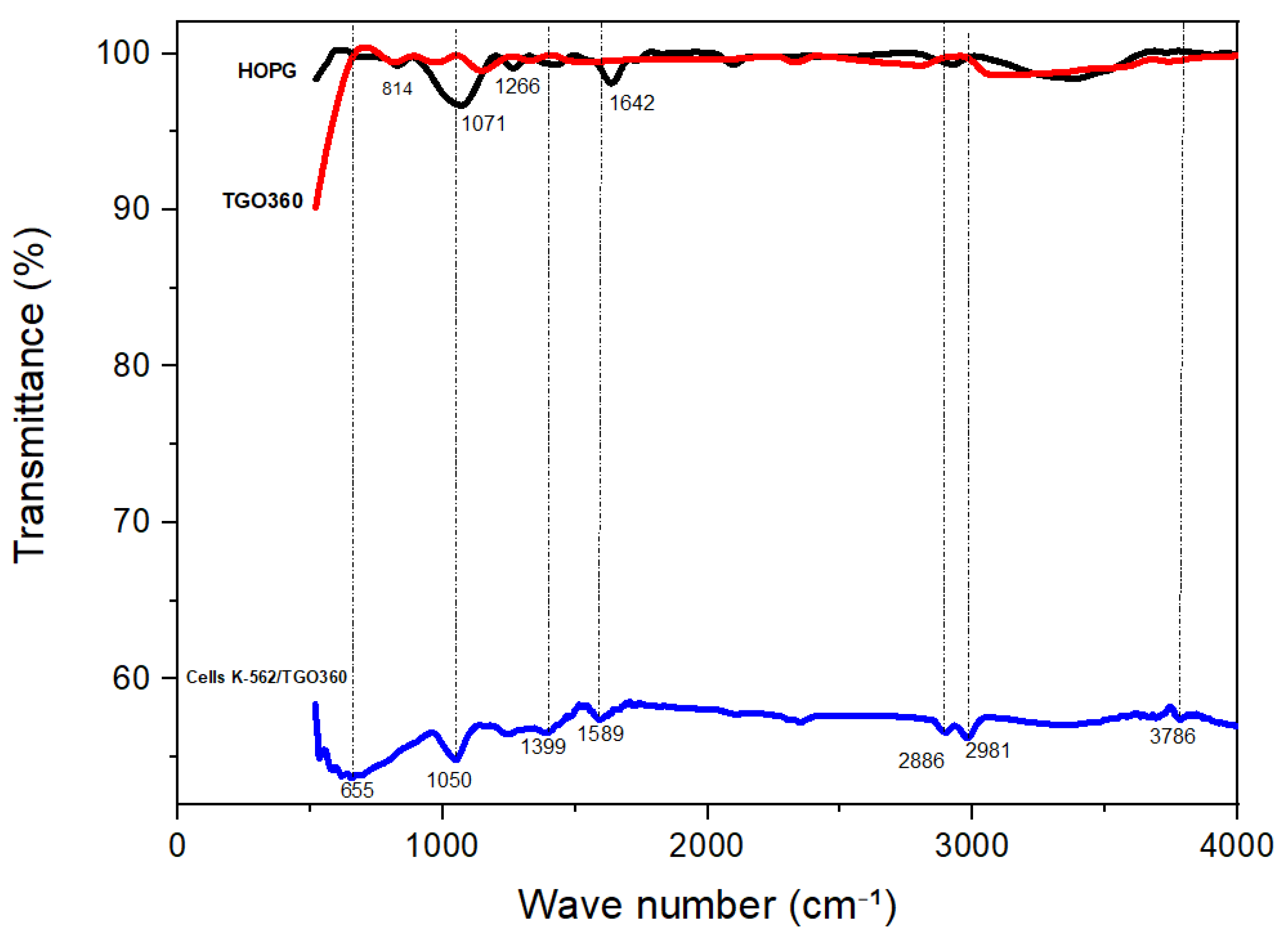

3.1. Characterization of the Electrode Materials

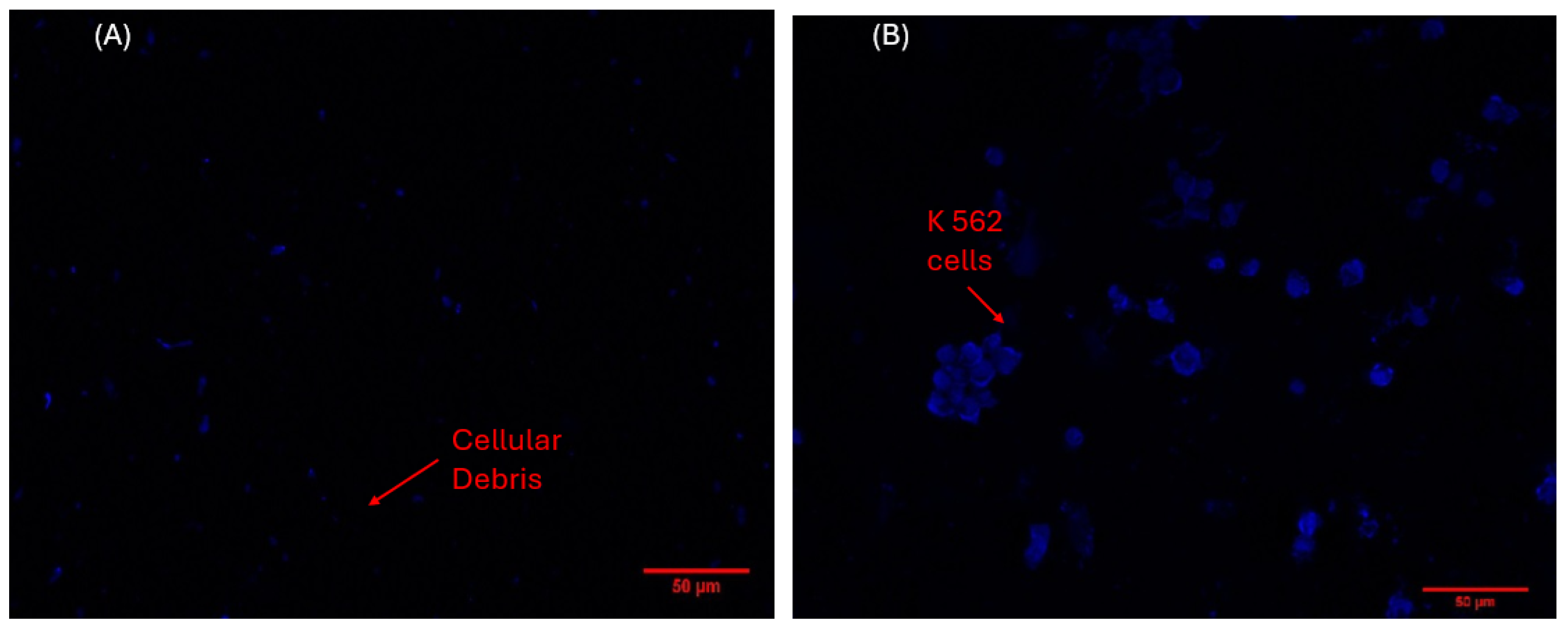

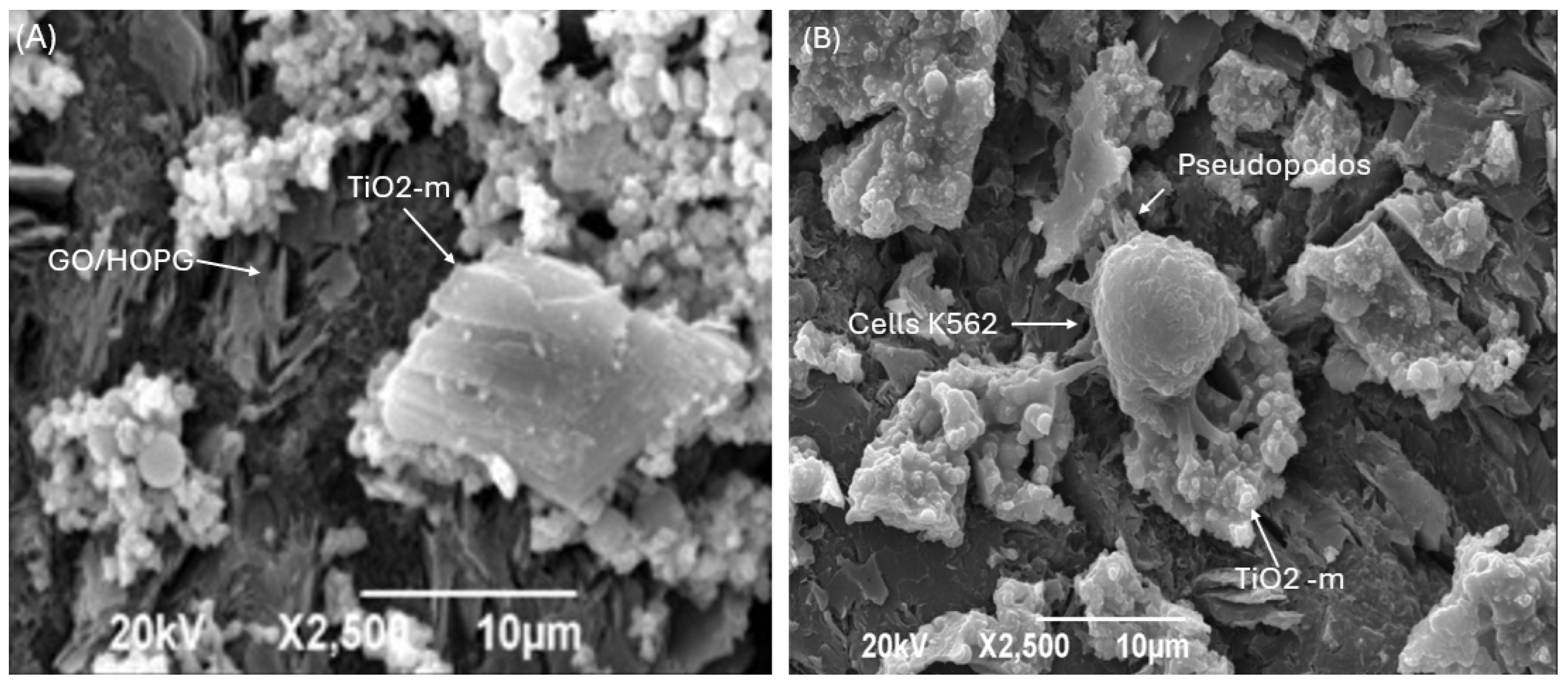

3.2. Analysis of Cellular Behavior on the Electrode Material

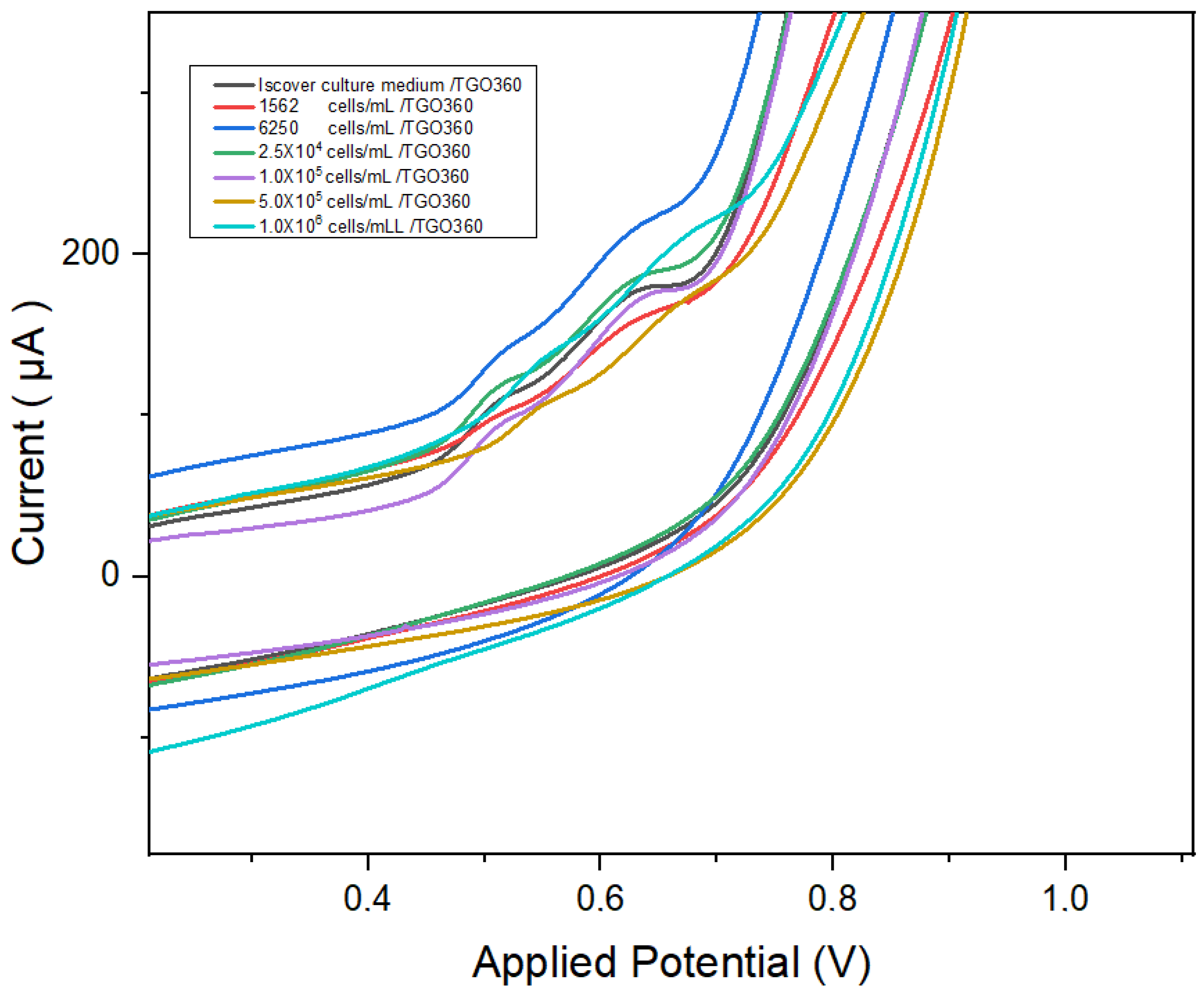

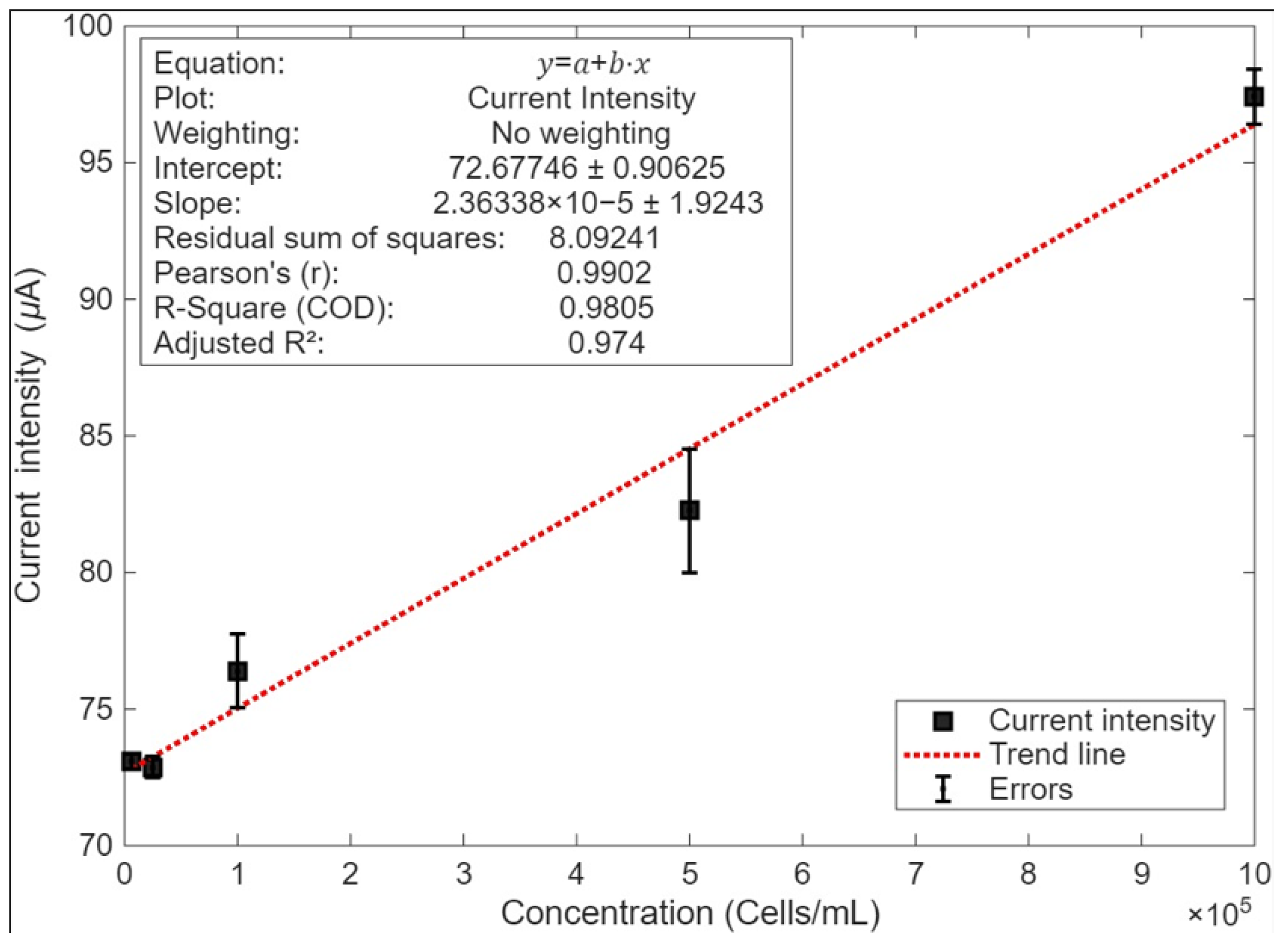

3.3. Electrochemical Detection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markham, M.J.; Wachter, K.; Agarwal, N.; Bertagnolli, M.M.; Chang, S.M.; Dale, W.; Diefenbach, C.S.M.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; George, D.J.; Gilligan, T.D.; et al. Clinical Cancer Advances 2020: Annual Report on Progress Against Cancer From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhanwar, S.C.; Xu, X.L.; Elahi, A.H.; Abramson, D.H. Cancer genomics of lung cancer including malignant mesothelioma: A brief overview of current status and future prospects. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2020, 78, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daci, M.; Berisha, L.; Mercatante, D.; Rodriguez-Estrada, M.T.; Jin, Z.; Huang, Y.; Amorati, R. Advancements in Biosensors for Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Protection in Food: A Critical Review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tanani, M.; Nsairat, H.; Matalka, I.I.; Lee, Y.F.; Rizzo, M.; Aljabali, A.A.; Mishra, V.; Mishra, Y.; Hromić-Jahjefendić, A.; Tambuwala, M.M. The impact of the BCR-ABL oncogene in the pathology and treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pathol.—Res. Pr. 2024, 254, 155161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Bahar, N.A.-H. Molecular Cytogenetic Study on BCR/ABL Fusion Gene in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Anbar, Al Anbar, Iraq, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hewison, A.; Atkin, K.; McCaughan, D.; Roman, E.; Smith, A.; Smith, G.; Howell, D. Experiences of living with chronic myeloid leukaemia and adhering to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 45, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Haghighi, A.M.; Misaghi, M. Nanosensors and their applications in early diagnosis of cancer. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 2023, 41, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, A.; Petrarca, C.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Mirabile, G.; Gangemi, S. Electrochemical Biosensors in the Diagnosis of Acute and Chronic Leukemias. Cancers 2022, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, R.; Reda, Y.; Abdel-Fattah, A. Review—Nanostructured Materials-Based Nanosensors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 037554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.-R.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, S. Molecularly imprinted poly(o-aminophenol)-based electrochemical sensor for the quantitative detection of a VP28 biomarker for white spot syndrome virus. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2025, 10, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Deng, D.; Song, Y.; Zhu, X.; Luo, L. Cascade signal amplifying strategy for ultrasensitive detection of tumor biomarker by DNAzyme cleaving mediated HCR. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 420, 136466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, P.; Mishra, P.; Islam, S.S. Sensitive biosensor for chronic myeloid leukemia detection using multi-wall carbon nanotube. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2276, 020025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toy, R.; Peiris, P.M.; Ghaghada, K.B.; Karathanasis, E. Shaping cancer nanomedicine: The effect of particle shape on the in vivo journey of nanoparticle. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Abdullaev, S.; Ali, F.K.; Naeem, Y.A.; Mizher, R.M.; Karim, M.M.; Abdulwahid, A.S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Habibzadeh, S.; et al. Nano titanium oxide (nano-TiO2): A review of synthesis methods, properties, and applications. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhanto, R.N.; Harimurti, S.; Septiani, N.L.W.; Utari, L.; Anshori, I.; Wasisto, H.S.; Suzuki, H.; Suyatman; Yuliarto, B. Sonochemical synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4/graphene nanocomposites for label-free electrochemical biosensors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 15381–15393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-L.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.-M.; Chen, B.-A. Detection and distinguishability of leukemia cancer cells based on Au nanoparticles modified electrodes. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrak, H.; Saied, T.; Chevallier, P.; Laroche, G.; M’nIf, A.; Hamzaoui, A.H. Synthesis, characterization, and functionalization of ZnO nanoparticles by N-(trimethoxysilylpropyl) ethylenediamine triacetic acid (TMSEDTA): Investigation of the interactions between Phloroglucinol and ZnO@TMSEDTA. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 4340–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, D.; Chen, H.; Yue, X.; Fan, K.; Dong, L.; Wang, G. Application of Silicon Nanowire Field Effect Transistor (SiNW-FET) Biosensor with High Sensitivity. Sensors 2023, 23, 6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, S.; Sivaram, K.; Sreejisha, N.; Murugesan, S. Nanomaterials-based Field Effect Transistor biosensor for cancer therapy. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 8, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăsceanu, G.M.; Amărandi, R.-M.; Ioniță, M.; Tite, T.; Iovu, H.; Pilan, L.; Burns, J.S. Versatile graphene biosensors for enhancing human cell therapy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 117, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Zhu, X.; Kong, X.Z. Preparation of hollow TiO2 nanoparticles through TiO2 deposition on polystyrene latex particles and characterizations of their structure and photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.A.; Rhim, J.-W. Effect of isolation methods of chitin nanocrystals on the properties of chitin-silver hybrid nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 197, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, M.A.M.; Julkapli, N.M.; Amir, M.N.I.; Maamor, A. Effect on different TiO2 photocatalyst supports on photodecolorization of synthetic dyes: A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, F.; Zazpe, R.; Krbal, M.; Sopha, H.; Prikryl, J.; Ng, S.; Hromadko, L.; Bures, F.; Macak, J.M. One-dimensional anodic TiO2 nanotubes coated by atomic layer deposition: Towards advanced applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2019, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WO2016055869—Synthesis of Nanocompounds Comprising Anatase-Phase Titanium Oxide And Compositions Containing Same For The Treatment Of Cancer. Available online: https://patentscope2.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2016055869 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wang, X.; Xia, X.; Zhang, X.; Meng, W.; Yuan, C.; Guo, M. Nonenzymatic glucose sensor based on Ag&Pt hollow nanoparticles supported on TiO2 nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 80, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, R.J.C.; Sevilla-Abarca, M.E. Método de funcionalización química para la obtención de óxido de grafeno adherido a la superficie de placas de grafito pirolítica de alta densidad por spray coating ácido. Ing. Y Compet. 2021, 23, e21110838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.D.; Kim, S.K.; Chang, H.; Roh, K.-M.; Choi, J.-W.; Huang, J. A glucose biosensor based on TiO2–Graphene composite. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 38, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US20170281770—Synthesis of Nanocompounds Comprising Anatase-phase Titanium Oxide and Compositions Containing Same for the Treatment of Cancer. Available online: https://patentscope2.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US204579236&_fid=WO2016055869 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Krishnan, S.K.; Singh, E.; Singh, P.; Meyyappan, M.; Singh Nalwa, H. A review on graphene-based nanocomposites for electrochemical and fluorescent biosensors. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 8778–8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, T.; Ohga, S.; Kishimoto, Y.; Kimura, T.; Ryo, R.; Sato, T. Scanning electron microscopic study of the adhesion of a human megakaryocytic leukemia cell line (CMK11-5). Med Mol. Morphol. 1993, 26, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Kong, Y.; Shen, Q.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Drug Evaluation Using a Multisignal Ampli fi ed Photoelectrochemical Sensing Platform. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 11680–11689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Du, D.; Wu, J.; Ju, H. A disposable impedance sensor for electrochemical study and monitoring of adhesion and proliferation of K562 leukaemia cells. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanghelini, F.; Frías, I.A.; Rêgo, M.J.; Pitta, M.G.; Sacilloti, M.; Oliveira, M.D.; Andrade, C.A. Biosensing breast cancer cells based on a three-dimensional TIO2 nanomembrane transducer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Bao, N.; Gu, H. A new disposable electrode for electrochemical study of leukemia K562 cells and anticancer drug sensitivity test. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 53, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Sheng, S.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Xie, G.; Feng, W. Coupling a universal DNA circuit with graphene sheets/polyaniline/AuNPs nanocomposites for the detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 889, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolaños, K.L.; Nagles, E.; Arancibia, V.; Otiniano, M.; Leiva, Y.; Mariño, A.; Scarpetta, L. Optimizing adsorption voltammetric technique (AdSV) in determining of amaranth on carbon printed electrodes. Eff. Surfactants Sensit. 2014, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Diosa, J.A.; Gonzalez Orive, A.; Grundmeier, G.; Camargo Amado, R.J.; Keller, A. Morphological Dynamics of Leukemia Cells on TiO 2 Nanoparticle Coatings Studied by AFM. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, J.; Li, J.; Xu, P.; Jiang, H.; Gu, J.; Wang, J. Ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor for detection of circulating tumor cells based on a highly efficient enzymatic cascade reaction. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 12966–12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Nanomaterial Engineered Biosensors and Stimulus–Responsive Platform for Emergency Monitoring and Intelligent Diagnosis. Biosensors 2025, 15, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhan, Y.; He, L. Graphene oxide/poly-l-lysine assembled layer for adhesion and electrochemical impedance detection of leukemia K562 cancercells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 42, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Bao, N.; Gu, H. Paper-based cell impedance sensor and its application for cytotoxic evaluation. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 325501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cui, M.; Niu, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S. Enhanced Peroxidase-Like Properties of Graphene–Hemin-Composite Decorated with Au Nanoflowers as Electrochemical Aptamer Biosensor for the Detection of K562 Leukemia Cancer Cells. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 18001–18008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, P.; Kaur, P.; Rajam, M.; Srivastava, T.; Mishra, P.; Islam, S. Single-wall carbon nanotube based electrochemical immunoassay for leukemia detection. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 557, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, P.; Kaur, P.; Rajam, M.; Srivastava, T.; Ali, A.; Mishra, P.; Islam, S. Leukemia biomarker detection by using photoconductive response of CNT electrode: Analysis of sensing mechanism based on charge transfer induced Fermi level fluctuation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 270, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.; Yan, M.; Yu, J. Electrochemical K-562 cells sensor based on origami paper device for point-of-care testing. Talanta 2015, 145, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafi, A.; Kim, T.-H.; An, J.H.; Choi, J.-W. Electrochemical cell-based chip for the detection of toxic effects of bisphenol-A on neuroblastoma cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 3371–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakht, M.; Pakbin, B.; Brujeni, G.N. Evaluation of a new lymphocyte proliferation assay based on cyclic voltammetry; an alternative method. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sevilla, M.E.; Amado, R.J.C.; Valle, P.R. Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of K-562 Leukemia Cells Using TiO2-Modified Graphite Nanostructured Electrode. Biosensors 2026, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010028

Sevilla ME, Amado RJC, Valle PR. Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of K-562 Leukemia Cells Using TiO2-Modified Graphite Nanostructured Electrode. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleSevilla, Martha Esperanza, Rubén Jesús Camargo Amado, and Pablo Raúl Valle. 2026. "Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of K-562 Leukemia Cells Using TiO2-Modified Graphite Nanostructured Electrode" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010028

APA StyleSevilla, M. E., Amado, R. J. C., & Valle, P. R. (2026). Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of K-562 Leukemia Cells Using TiO2-Modified Graphite Nanostructured Electrode. Biosensors, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010028