Nanoparticle Detection in Biology and Medicine: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Non-Invasive Methods of Nanoparticle Detection In Vivo

2.1. Magnetic-Based Techniques

2.1.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles as Contrast Agents

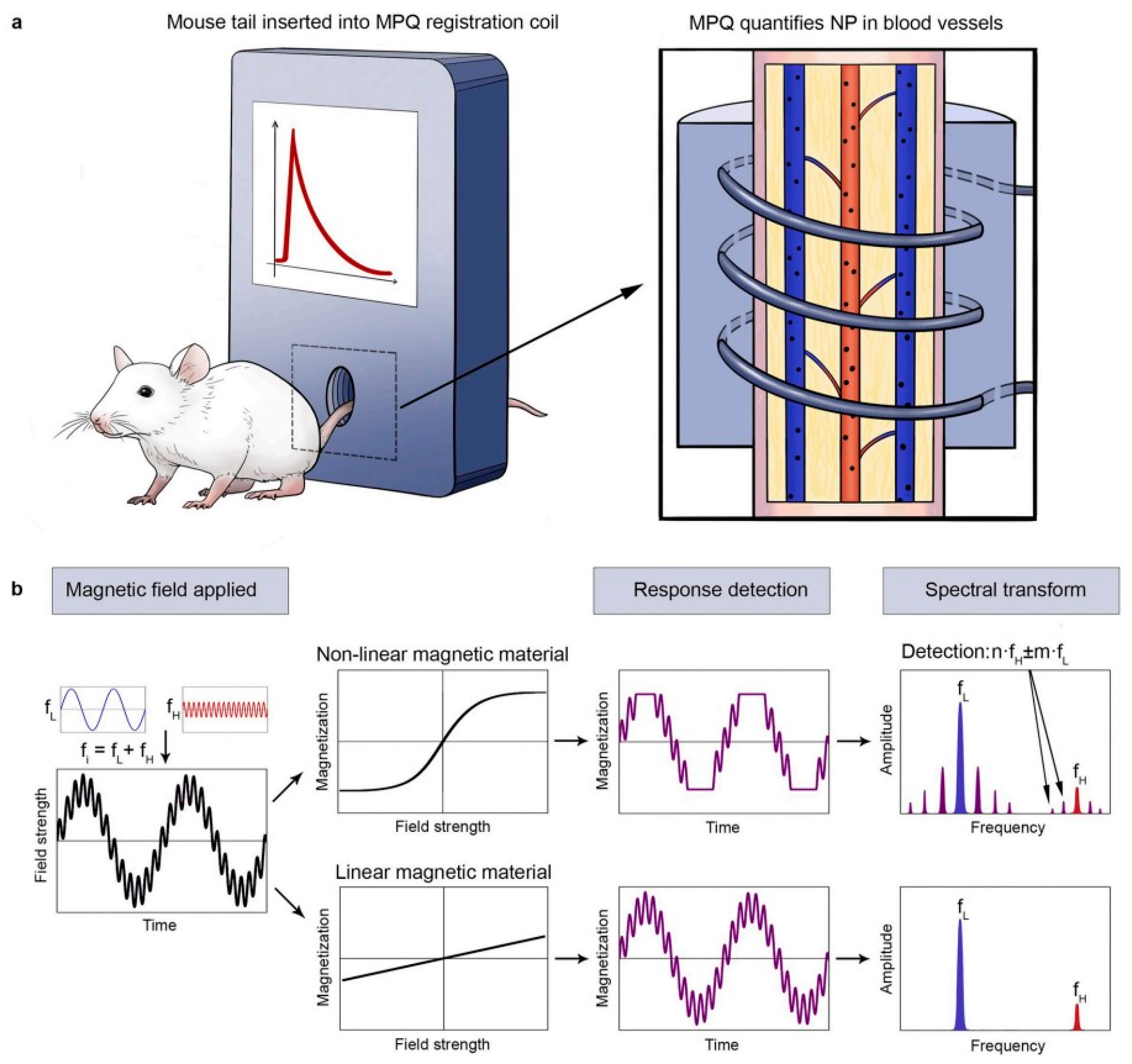

2.1.2. Magnetic Particle Quantification

2.2. Acoustic and Hybrid Techniques

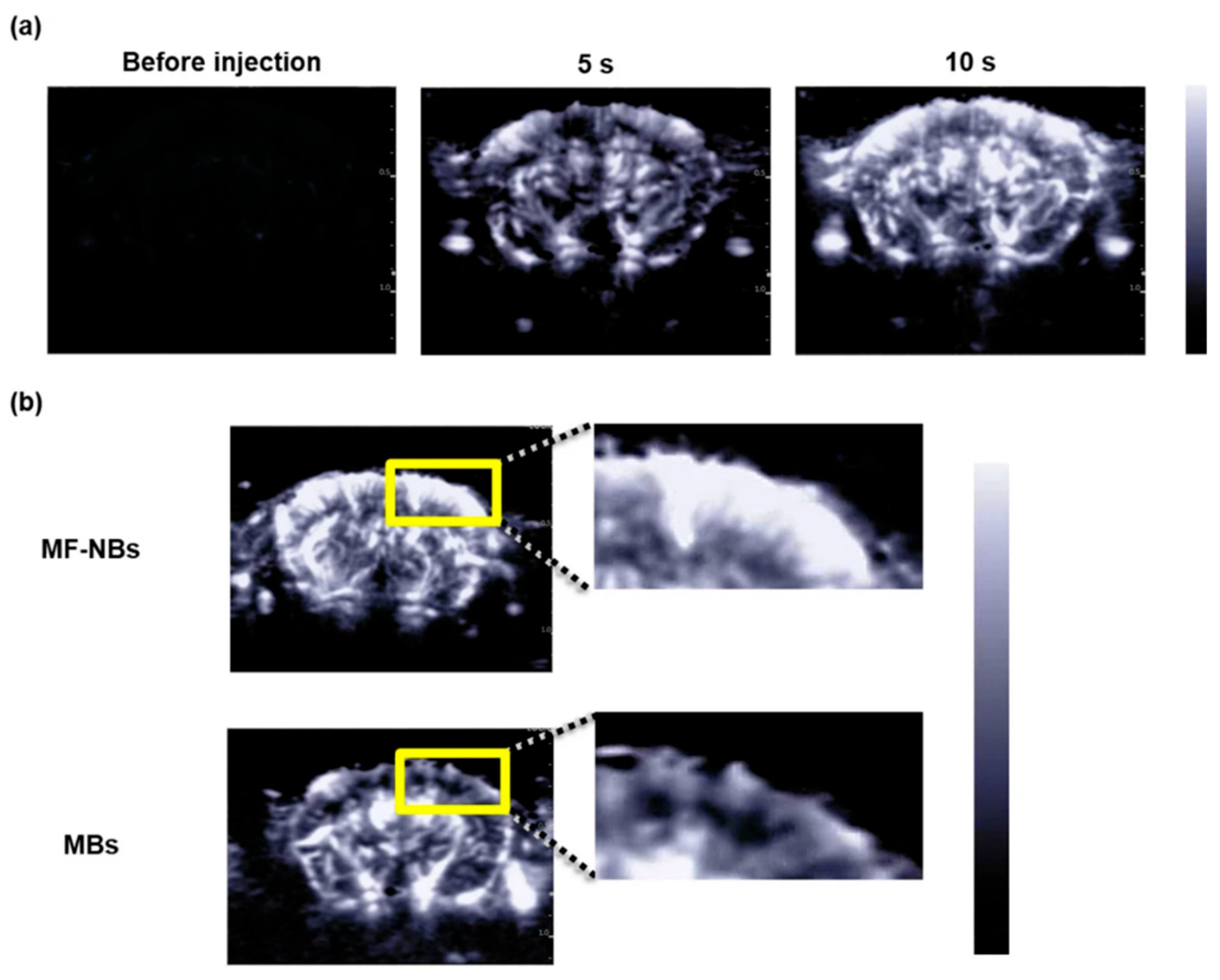

2.2.1. Ultrasound Imaging with Nanoparticle-Based Contrast Agents

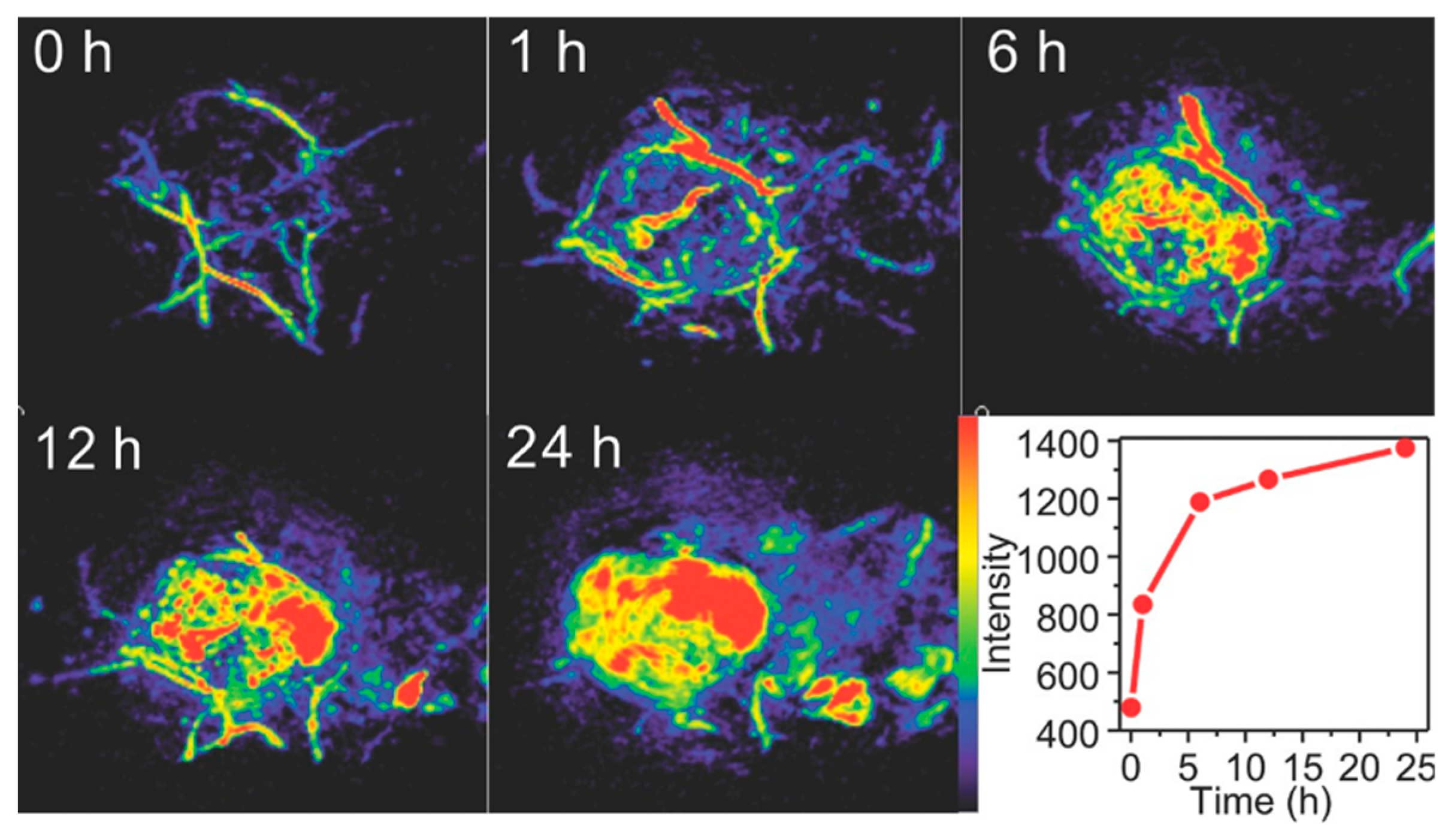

2.2.2. Photoacoustic Imaging

2.3. Optical Techniques

2.3.1. Fluorescence Tomography for the Detection of Fluorescent Nanoparticles

2.3.2. Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging

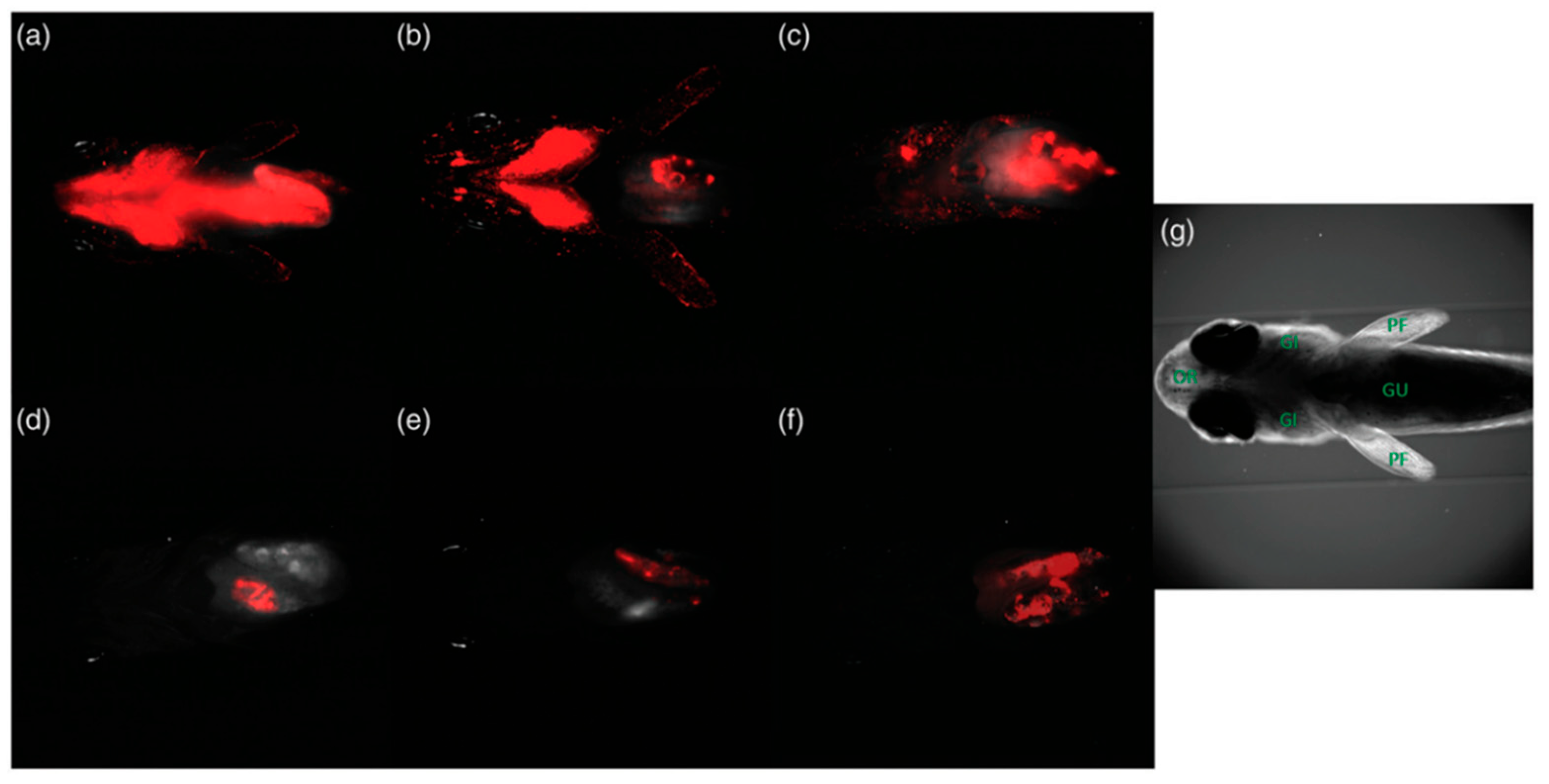

2.3.3. Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy

2.3.4. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Tomography for Nanoparticle Detection

2.3.5. Photon Correlation Spectroscopy and Related Methods

2.4. X-Ray and Nuclear Techniques

2.4.1. Computed Tomography for the Detection of High-Z Nanoparticles

2.4.2. Radiolabeled Nanoparticles for PET, SPECT, and Cherenkov Luminescence Imaging

2.4.3. X-Ray Fluorescence

2.5. Flow-Based and Cytometry-like Techniques

In Vivo Flow Cytometry

3. Ex Vivo and Invasive Methods for Nanoparticle Detection

3.1. Microscopy-Based Methods

3.1.1. Electron Microscopy for Nanoparticle Visualization

3.1.2. Confocal and Fluorescence Microscopy in Nanoparticle Research

3.1.3. Multiphoton Microscopy (2P/3P) for Nanoparticle Imaging

3.1.4. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy

3.1.5. Atomic Force Microscopy

3.1.6. Photothermal Microscopy

3.2. Cytometry-Based Methods

3.2.1. Flow Cytometry

3.2.2. MPQ-Cytometry

3.2.3. Cytometry by Time-of-Flight

3.3. Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods

3.3.1. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry

3.3.2. Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry

3.3.3. Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry

3.4. Biochemical and Luminescent Methods

3.4.1. Chemiluminescent Analysis

3.4.2. Bioluminescent Methods

3.5. Combined and Hybrid Methods

Autoradiography

3.6. Local Biochemical and Histological Methods

3.6.1. Histology with Staining

3.6.2. Immunohistochemistry

3.6.3. Western Blot/ELISA

3.6.4. RT-qPCR/In Situ Hybridization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFM | atomic force microscopy |

| AR | autoradiography |

| BL | bioluminescence |

| CCD | charge-coupled devices |

| CISH | chromogenic in situ hybridization |

| CL | chemiluminescence |

| CLI | Cherenkov Luminescence Imaging |

| CMOS | complementary metal-oxide semiconductor |

| CRET | Cherenkov radiation energy transfer |

| CT | computed tomography |

| CTC | circulating tumor cells |

| CyTOF | cytometry by time-of-flight |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EM | electron microscopy |

| FCM | flow cytometry |

| FDA | Food and Drugs Administration |

| FDG | fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FISH | fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| FITC | fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FLIM | fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy |

| FRET | Förster resonance energy transfer |

| FSC | forward scatter |

| FCS | fluorescence correlation spectroscopy |

| HER2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| ICP | inductively coupled plasma |

| ICP-MS | inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| ICP-TOF-MS | inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| ICG | indocyanine green |

| ID | injected dose |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| ISH | in situ hybridization |

| IVFC | in vivo flow cytometry |

| LA-ICP-MS | laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LSFM | light sheet fluorescence microscopy |

| MMUS | magnetomotive ultrasound |

| MNP | magnetic nanoparticle |

| MPQ | magnetic particle quantification |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NIR | near-infrared |

| NP | nanoparticles |

| PAI | photoacoustic imaging |

| PALM | photoactivated localization microscopy |

| PAM | photoacoustic microscopy |

| PAT | photoacoustic tomography |

| PCS | photon correlation spectroscopy |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| PLGA | poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid |

| SAIO | supramolecular amorphous-like iron oxide nanoparticles |

| SDD | silicon drift detector |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SERS | surface-enhanced Raman scattering |

| SIM | structured illumination microscopy |

| siRNAs | small interfering RNAs |

| SP-ICP-MS | single-particle ICP-MS |

| SPECT | single photon emission computed tomography |

| SPION | superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles |

| SSC | side scatter |

| STED | stimulated emission depletion |

| STORM | stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy |

| SWIR | short-wave infrared |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| ToF-SIMS | time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry |

| USI | ultrasound imaging |

| XPCS | X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

References

- Gingerich, O.; van Helden, A. From OCCHIALE to Printed Page: The Making of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius. J. Hist. Astron. 2003, 34, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2016, 1, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2019, 4, e10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, M.R.; Cheeseman, S.; White, S.; Margison, J. Caelyx (stealth liposomal doxorubicin) in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2001, 37, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiecicki, P.L.; Zhen, D.B.; Mauermann, M.L.; Kyle, R.A.; Zeldenrust, S.R.; Grogan, M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Gertz, M.A. Hereditary ATTR amyloidosis: A single-institution experience with 266 patients. Amyloid 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Robert-Nicoud, G.; Herrera Hidalgo, C.; Borg, M.L.; Iqbal, M.N.; Berlin, R.; Lindgren, M.; Waara, E.; Uddén, A.; Pietiläinen, K.; et al. Engineered mesoporous silica reduces long-term blood glucose, HbA1c, and improves metabolic parameters in prediabetics. Nanomedicine 2022, 17, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilliot, S.; Wilson, E.N.; Touchon, J.; Soto, M.E. Nanolithium, a New Treatment Approach to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Existing Evidence and Clinical Perspectives. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundekkad, D.; Cho, W.C. Nanoparticles in Clinical Translation for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulldemolins, A.; Seras-Franzoso, J.; Andrade, F.; Rafael, D.; Abasolo, I.; Gener, P.; Schwartz, S. Perspectives of nano-carrier drug delivery systems to overcome cancer drug resistance in the clinics. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zaks, T.; Langer, R.; Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J. Inorganic nanoparticles in clinical trials and translations. Nano Today 2020, 35, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, M.P.; Zelepukin, I.V.; Shipunova, V.O.; Sokolov, I.L.; Deyev, S.M.; Nikitin, P.I. Enhancement of the blood-circulation time and performance of nanomedicines via the forced clearance of erythrocytes. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelepukin, I.V.; Yaremenko, A.V.; Shipunova, V.O.; Babenyshev, A.V.; Balalaeva, I.V.; Nikitin, P.I.; Deyev, S.M.; Nikitin, M.P. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery via RBC-hitchhiking for the inhibition of lung metastases growth. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.-H.; Kim, C.-S.; Kim, J. Review on Optical Imaging Techniques for Multispectral Analysis of Nanomaterials. Nanotheranostics 2022, 6, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ali, M.R.K.; Chen, K.; Fang, N.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold nanoparticles in biological optical imaging. Nano Today 2019, 24, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Cheon, S.Y.; Park, S.; Lee, D.; Lee, Y.; Han, S.; Kim, M.; Koo, H. Recent advances in optical imaging through deep tissue: Imaging probes and techniques. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Niu, W.; Du, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Su, D.; Gao, X. 64Cu radiolabeled nanomaterials for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3349–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Mackeyev, Y.; Krishnan, S. Radiolabeled nanomaterial for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics: Principles and concepts. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2023, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellico, J.; Gawne, P.J.; de Rosales, R.T.M. Radiolabelling of nanomaterials for medical imaging and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3355–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinha, P.; Coelho, J.M.P.; Reis, C.P.; Gaspar, M.M. A Comprehensive Updated Review on Magnetic Nanoparticles in Diagnostics. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materón, E.M.; Miyazaki, C.M.; Carr, O.; Joshi, N.; Picciani, P.H.S.; Dalmaschio, C.J.; Davis, F.; Shimizu, F.M. Magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Roy, I.; Gandhi, S. Magnetic Nanoparticles: An Overview for Biomedical Applications. Magnetochemistry 2022, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Tavares, A.J.; Dai, Q.; Ohta, S.; Audet, J.; Dvorak, H.F.; Chan, W.C.W. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.S.L.; Stern, S.T.; Deal, A.M.; Kabanov, A.V.; Zamboni, W.C. A reanalysis of nanoparticle tumor delivery using classical pharmacokinetic metrics. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.R.; Hall, A.S.; Pallis, C.A.; Legg, N.J.; Bydder, G.M.; Steiner, R.E. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1981, 2, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Fox, N.C.; Jack, C.R.; Scheltens, P.; Thompson, P.M. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, M.; Waters, J.; Morris, E. MRI for breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet 2011, 378, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, V.P.B.; Tognarelli, J.M.; Crossey, M.M.E.; Cox, I.J.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; McPhail, M.J.W. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles and Techniques: Lessons for Clinicians. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2015, 5, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senft, C.; Bink, A.; Franz, K.; Vatter, H.; Gasser, T.; Seifert, V. Intraoperative MRI guidance and extent of resection in glioma surgery: A randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, A.G.; Hendrikse, J.; Zwanenburg, J.J.M.; Visser, F.; Luijten, P.R. Clinical applications of 7 T MRI in the brain. Eur. J. Radiol. 2013, 82, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegafaw, T.; Liu, S.; Ahmad, M.Y.; Saidi, A.K.A.A.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Nam, S.-W.; Chang, Y.; Lee, G.H. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based High-Performance Positive and Negative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.-H.; Kim, P.K.; Kang, S.; Cheong, J.; Kim, S.; Lim, Y.; Shin, W.; Jung, J.-Y.; Lah, J.D.; Choi, B.W.; et al. High-resolution T1 MRI via renally clearable dextran nanoparticles with an iron oxide shell. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.J.J.; Oakden, W.; Stanisz, G.J.; Scott Prosser, R.; van Veggel, F.C.J.M. Size-Tunable, Ultrasmall NaGdF 4 Nanoparticles: Insights into Their T 1 MRI Contrast Enhancement. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 3714–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Ronald, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, D.; Pandit, P.; Ma, M.L.; Rutt, B.; Rao, J. Controlled self-assembling of gadolinium nanoparticles as smart molecular magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 6283–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdick, S.D.; Jordanova, K.V.; Lundstrom, J.T.; Parigi, G.; Poorman, M.E.; Zabow, G.; Keenan, K.E. Iron oxide nanoparticles as positive T1 contrast agents for low-field magnetic resonance imaging at 64 mT. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Iron-oxide Nanoparticles in the era of Personalized Medicine. Nanotheranostics 2023, 7, 424–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangijzegem, T.; Lecomte, V.; Ternad, I.; van Leuven, L.; Muller, R.N.; Stanicki, D.; Laurent, S. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPION): From Fundamentals to State-of-the-Art Innovative Applications for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y.; Han, S.; Howerton, B.; Marti, F.; Weeks, J.; Gedaly, R.; Adatorwovor, R.; Chapelin, F. Receptor-Mediated SPION Labeling of CD4+ T Cells for Longitudinal MRI Tracking of Distribution Following Systemic Injection in Mouse. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, M.; Opiła, G.; Hinz, A.; Stankiewicz, S.; Bzowska, M.; Wolski, K.; Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Przewoźnik, J.; Kapusta, C.; Karewicz, A. Hyaluronic Acid-Coated SPIONs with Attached Folic Acid as Potential T2 MRI Contrasts for Anticancer Therapies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 9059–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özel, D.; Yurt, F. Synthesis and characterization of manganese-loaded core-shell SPIONs for dual T1/T2 weighted MR imaging applications in breast cancer. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 179, 114713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Lee, N.; Kim, H.; An, K.; Park, Y.I.; Choi, Y.; Shin, K.; Lee, Y.; Kwon, S.G.; Na, H.B.; et al. Large-scale synthesis of uniform and extremely small-sized iron oxide nanoparticles for high-resolution T1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12624–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-H.; Li, F.-C.; Souris, J.S.; Yang, C.-S.; Tseng, F.-G.; Lee, H.-S.; Chen, C.-T.; Dong, C.-Y.; Lo, L.-W. Visualizing dynamics of sub-hepatic distribution of nanoparticles using intravital multiphoton fluorescence microscopy. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 4122–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Na, Y.R.; Na, C.M.; Im, P.W.; Park, H.W.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, Y.; You, J.H.; Kang, D.S.; Moon, H.E.; et al. 7-nm Mn0.5 Zn0.5Fe2O4 superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (SPION): A high-performance theranostic for MRI and hyperthermia applications. Theranostics 2025, 15, 2883–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, O.A.; Komedchikova, E.N.; Zvereva, S.D.; Obozina, A.S.; Dorozh, O.V.; Afanasev, I.; Nikitin, P.I.; Mochalova, E.N.; Nikitin, M.P.; Shipunova, V.O. Albumin incorporation into recognising layer of HER2-specific magnetic nanoparticles as a tool for optimal targeting of the acidic tumor microenvironment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rümenapp, C.; Gleich, B.; Haase, A. Magnetic nanoparticles in magnetic resonance imaging and diagnostics. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faucher, L.; Guay-Bégin, A.-A.; Lagueux, J.; Côté, M.-F.; Petitclerc, E.; Fortin, M.-A. Ultra-small gadolinium oxide nanoparticles to image brain cancer cells in vivo with MRI. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2011, 6, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Zhong, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Mao, H. Improving the magnetic resonance imaging contrast and detection methods with engineered magnetic nanoparticles. Theranostics 2012, 2, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’annunziata, M.F. (Ed.) Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis: Volume 2; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128143957. [Google Scholar]

- Si, G.; Hapuarachchige, S.; Artemov, D. Ultrasmall Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as Nanocarriers for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Development and In Vivo Characterization. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 9625–9632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.-L.; Yoshida, T.; Kathuria-Prakash, N.; Zaki, I.H.; Varallyay, C.G.; Semple, S.I.; Saouaf, R.; Rigsby, C.K.; Stoumpos, S.; Whitehead, K.K.; et al. Multicenter Safety and Practice for Off-Label Diagnostic Use of Ferumoxytol in MRI. Radiology 2019, 293, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wáng, Y.X.J.; Idée, J.-M. A comprehensive literatures update of clinical researches of superparamagnetic resonance iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2017, 7, 88–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellico, J.; Ruiz-Cabello, J.; Herranz, F. Radiolabeled Iron Oxide Nanomaterials for Multimodal Nuclear Imaging and Positive Contrast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 20523–20538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, H.T.; Li, Z.; Hagemeyer, C.E.; Cowin, G.; Zhang, S.; Palasubramaniam, J.; Alt, K.; Wang, X.; Peter, K.; Whittaker, A.K. Molecular imaging of activated platelets via antibody-targeted ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles displaying unique dual MRI contrast. Biomaterials 2017, 134, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieda, N.; van der Pol, C.B.; Walker, D.; Tsampalieros, A.K.; Maralani, P.J.; Woo, S.; Davenport, M.S. Adverse Events to the Gadolinium-based Contrast Agent Gadoxetic Acid: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology 2020, 297, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhu, Y.-N.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Sun, B.; Yan, F.; et al. A deep unrolled neural network for real-time MRI-guided brain intervention. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipunova, V.O.; Nikitin, M.P.; Nikitin, P.I.; Deyev, S.M. MPQ-cytometry: A magnetism-based method for quantification of nanoparticle-cell interactions. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12764–12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipunova, V.O.; Kolesnikova, O.A.; Kotelnikova, P.A.; Soloviev, V.D.; Popov, A.A.; Proshkina, G.M.; Nikitin, M.P.; Deyev, S.M. Comparative Evaluation of Engineered Polypeptide Scaffolds in HER2-Targeting Magnetic Nanocarrier Delivery. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 16000–16008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, V.L.; Komedchikova, E.N.; Sogomonyan, A.S.; Tereshina, E.D.; Kolesnikova, O.A.; Mirkasymov, A.B.; Iureva, A.M.; Zvyagin, A.V.; Nikitin, P.I.; Shipunova, V.O. Lectin-Modified Magnetic Nano-PLGA for Photodynamic Therapy In Vivo. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaev, I.B.; Mirkasymov, A.B.; Rodionov, V.I.; Babkova, J.S.; Nikitin, P.I.; Deyev, S.M.; Zelepukin, I.V. MPS blockade with liposomes controls pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles in a size-dependent manner. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 19, 065022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlov, A.V.; Bragina, V.A.; Nikitin, M.P.; Nikitin, P.I. Rapid dry-reagent immunomagnetic biosensing platform based on volumetric detection of nanoparticles on 3D structures. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipunova, V.O.; Nikitin, M.P.; Belova, M.M.; Deyev, S.M. Label-free methods of multiparametric surface plasmon resonance and MPQ-cytometry for quantitative real-time measurements of targeted magnetic nanoparticles complexation with living cancer cells. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, M.P.; Orlov, A.V.; Znoyko, S.L.; Bragina, V.A.; Gorshkov, B.G.; Ksenevich, T.I.; Cherkasov, V.R.; Nikitin, P.I. Multiplex biosensing with highly sensitive magnetic nanoparticle quantification method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 459, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, M.P.; Orlov, A.V.; Sokolov, I.L.; Minakov, A.A.; Nikitin, P.I.; Ding, J.; Bader, S.D.; Rozhkova, E.A.; Novosad, V. Ultrasensitive detection enabled by nonlinear magnetization of nanomagnetic labels. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 11642–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregubov, A.A.; Sokolov, I.L.; Babenyshev, A.V.; Nikitin, P.I.; Cherkasov, V.R.; Nikitin, M.P. Magnetic hybrid magnetite/metal organic framework nanoparticles: Facile preparation, post-synthetic biofunctionalization and tracking in vivo with magnetic methods. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 449, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozhnikov, D.; Babenyshev, A.V.; Kovaleva, A.Y.; Yakovtseva, M.N.; Lunin, A.V.; Lyfanov, D.A.; Nikitin, M.P. Synthesis of Fluorescent and Magnetic Liposomes and Their Application for Optical Detection of Migrating Cancer Cells. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference Laser Optics (ICLO), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2–6 November 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 1, ISBN 978-1-7281-5232-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin, M.P.; Torno, M.; Chen, H.; Rosengart, A.; Nikitin, P.I. Quantitative real-time in vivo detection of magnetic nanoparticles by their nonlinear magnetization. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07A304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabashvili, A.N.; Znoyko, S.L.; Ryabova, A.V.; Mochalova, E.N.; Griaznova, O.Y.; Tortunova, T.A.; Sheveleva, O.N.; Butorina, N.N.; Kuziaeva, V.I.; Lyadova, I.V.; et al. Multimodal Detection of Magnetically and Fluorescently Dual-Labeled Murine Macrophages After Intravenous Administration. Molecules 2025, 30, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaremenko, A.V.; Zelepukin, I.V.; Ivanov, I.N.; Melikov, R.O.; Pechnikova, N.A.; Dzhalilova, D.S.; Mirkasymov, A.B.; Bragina, V.A.; Nikitin, M.P.; Deyev, S.M.; et al. Influence of magnetic nanoparticle biotransformation on contrasting efficiency and iron metabolism. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelepukin, I.V.; Yaremenko, A.V.; Yuryev, M.V.; Mirkasymov, A.B.; Sokolov, I.L.; Deyev, S.M.; Nikitin, P.I.; Nikitin, M.P. Fast processes of nanoparticle blood clearance: Comprehensive study. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Du, M.; Chen, Z. Nanosized Contrast Agents in Ultrasound Molecular Imaging. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 758084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ye, H.-R.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Z.-Z. Ultrasound Molecular Imaging and Its Applications in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 2857–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sui, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, W.; Guo, Q.; Sun, J.; Jing, F. Perfluorooctylbromide nanoparticles for ultrasound imaging and drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 3053–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuncu, S.; Javier Ramirez, R.; Fischer, J.M.; Civitci, F.; Yildirim, A. Ultrafast Background-Free Ultrasound Imaging Using Blinking Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Endo-Takahashi, Y.; Awaji, K.; Numazawa, S.; Onishi, Y.; Tada, R.; Ogasawara, M.; Takizawa, Y.; Kurumizaka, H.; Negishi, Y. Microfluidic nanobubbles produced using a micromixer for ultrasound imaging and gene delivery. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, L.; Yan, F.; Zheng, H. Nanoscale contrast agents: A promising tool for ultrasound imaging and therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 207, 115200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupillo, E.; Bianchi, E.; Bonetto, V.; Pasetto, L.; Bendotti, C.; Paganoni, S.; Mandrioli, J.; Mazzini, L. Long-term survival of participants in a phase II randomized trial of RNS60 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 122, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöstrand, S.; Evertsson, M.; Jansson, T. Magnetomotive Ultrasound Imaging Systems: Basic Principles and First Applications. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 2636–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.R.; Frey, W.; Emelianov, S. Quantitative photoacoustic imaging of nanoparticles in cells and tissues. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrueck, A.; Karges, J. Metal Complexes and Nanoparticles for Photoacoustic Imaging. Chembiochem 2023, 24, e202300079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tang, S.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Mo, S.; Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Zheng, N. Core-shell Pd@Au nanoplates as theranostic agents for in-vivo photoacoustic imaging, CT imaging, and photothermal therapy. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 8210–8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijblom, M.; Piras, D.; Brinkhuis, M.; van Hespen, J.C.G.; van den Engh, F.M.; van der Schaaf, M.; Klaase, J.M.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Steenbergen, W.; Manohar, S. Photoacoustic image patterns of breast carcinoma and comparisons with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and vascular stained histopathology. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuker, F.; Ripoll, J.; Rudin, M. Fluorescence molecular tomography: Principles and potential for pharmaceutical research. Pharmaceutics 2011, 3, 229–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, K.; Bednarkiewicz, A.; Liu, X.; Jin, D. Advances in highly doped upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.A.; Boas, D.A.; Li, X.D.; Chance, B.; Yodh, A.G. Fluorescence lifetime imaging in turbid media. Opt. Lett. 1996, 21, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, C.; Song, F.; Fan, G.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, G. A review of advances in imaging methodology in fluorescence molecular tomography. Phys. Med. Biol. 2022, 67, 10TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-Ibáñez, E.; Faruqu, F.N.; Saleh, A.F.; Silva, A.M.; Tzu-Wen Wang, J.; Rak, J.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Dekker, N. Selection of Fluorescent, Bioluminescent, and Radioactive Tracers to Accurately Reflect Extracellular Vesicle Biodistribution in Vivo. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3212–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iureva, A.M.; Nikitin, P.I.; Tereshina, E.D.; Nikitin, M.P.; Shipunova, V.O. The influence of various polymer coatings on the in vitro and in vivo properties of PLGA nanoparticles: Comprehensive study. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 201, 114366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.-H.; Cheng, S.-H.; Chen, N.-T.; Liao, W.-N.; Lo, L.-W. Microwave-Synthesized Platinum-Embedded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as Dual-Modality Contrast Agents: Computed Tomography and Optical Imaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-S.; Chiu, D.T. Soft fluorescent nanomaterials for biological and biomedical imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4699–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tian, J.; Yong, K.-T.; Zhu, X.; Lin, M.C.-M.; Jiang, W.; Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Lin, G. Immunotoxicity assessment of CdSe/ZnS quantum dots in macrophages, lymphocytes and BALB/c mice. J. Nanobiotechnology 2016, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-F.; Li, Y.-H.; Fang, Y.-W.; Xu, Y.; Wei, X.-M.; Yin, X.-B. Carbon Quantum Dots for Zebrafish Fluorescence Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yukawa, H.; Baba, Y. In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging and the Diagnosis of Stem Cells Using Quantum Dots for Regenerative Medicine. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2671–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komedchikova, E.N.; Kolesnikova, O.A.; Syuy, A.V.; Volkov, V.S.; Deyev, S.M.; Nikitin, M.P.; Shipunova, V.O. Targosomes: Anti-HER2 PLGA nanocarriers for bioimaging, chemotherapy and local photothermal treatment of tumors and remote metastases. J. Control. Release 2024, 365, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonova, A.O.; Kolesnikova, O.A.; Ivantcova, P.M.; Gubaidullina, M.A.; Shipunova, V.O. Comparative Analysis of Stabilization Methods for Silver Nanoprisms As Promising Nanobiomedicine Agents. Nanobiotechnology Rep. 2024, 19, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, S.-C.; Zhu, M.-H.; Zhu, X.-D.; Luan, X.; Liu, X.-L.; Lai, X.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, Q.; Sun, P.; et al. Metal Phenolic Network-Integrated Multistage Nanosystem for Enhanced Drug Delivery to Solid Tumors. Small 2021, 17, e2100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; He, X.; Yang, X.; Shi, H. Functionalized silica nanoparticles: A platform for fluorescence imaging at the cell and small animal levels. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Z.; Li, G. Application of upconversion rare earth fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical drug delivery system. J. Lumin. 2020, 223, 117226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, K.J.; Jing, L.; Behrens, A.M.; Jayawardena, S.; Tang, W.; Gao, M.; Langer, R.; Jaklenec, A. Biocompatible Semiconductor Quantum Dots as Cancer Imaging Agents. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1706356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogomonyan, A.S.; Deyev, S.M.; Shipunova, V.O. Internalization-Responsive Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Nanoparticles for Image-Guided Photodynamic Therapy against HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 11402–11415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntziachristos, V.; Weissleder, R. Charge-coupled-device based scanner for tomography of fluorescent near-infrared probes in turbid media. Med. Phys. 2002, 29, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swy, E.R.; Schwartz-Duval, A.S.; Shuboni, D.D.; Latourette, M.T.; Mallet, C.L.; Parys, M.; Cormode, D.P.; Shapiro, E.M. Dual-modality, fluorescent, PLGA encapsulated bismuth nanoparticles for molecular and cellular fluorescence imaging and computed tomography. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 13104–13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Kuo, T.-R.; Su, H.-J.; Lai, W.-Y.; Yang, P.-C.; Chen, J.-S.; Wang, D.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-C. Fluorescence-Guided Probes of Aptamer-Targeted Gold Nanoparticles with Computed Tomography Imaging Accesses for in Vivo Tumor Resection. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipunova, V.O.; Komedchikova, E.N.; Kotelnikova, P.A.; Nikitin, M.P.; Deyev, S.M. Targeted Two-Step Delivery of Oncotheranostic Nano-PLGA for HER2-Positive Tumor Imaging and Therapy In Vivo: Improved Effectiveness Compared to One-Step Strategy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfe, P. In vivo near-infrared spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 2, 715–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, E.; Su, Y.; Cheng, T.; Shi, C. A review of NIR dyes in cancer targeting and imaging. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7127–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Antaris, A.L.; Dai, H. Near-infrared fluorophores for biomedical imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Mao, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Mazhar, M.; Ma, Y.; Yang, S.; Ren, W. Design and Application of Near-Infrared Nanomaterial-Liposome Hybrid Nanocarriers for Cancer Photothermal Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Liu, B. Polymer-encapsulated organic nanoparticles for fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6570–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-Y.; Zhu, S.; Cui, R.; Zhang, M. Noninvasive In Vivo Imaging in the Second Near-Infrared Window by Inorganic Nanoparticle-Based Fluorescent Probes. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Carroll, G.M.; Neale, N.R.; Beard, M.C. Infrared Quantum Dots: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilderbrand, S.A.; Weissleder, R. Near-infrared fluorescence: Application to in vivo molecular imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, X.; Wang, K.; Xie, C.; Zhou, B.; Qing, Z. Ultrasmall near-infrared gold nanoclusters for tumor fluorescence imaging in vivo. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 2244–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Yoon, H.Y.; Lim, S.; Stayton, P.S.; Kim, I.-S.; Kim, K.; Kwon, I.C. In vivo tracking of bioorthogonally labeled T-cells for predicting therapeutic efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy. J. Control. Release 2021, 329, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Lee, J.C.; Jha, A.; Diao, S.; Nakayama, K.H.; Hou, L.; Doyle, T.C.; Robinson, J.T.; Antaris, A.L.; Dai, H.; et al. Near-infrared II fluorescence for imaging hindlimb vessel regeneration with dynamic tissue perfusion measurement. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, X.; Li, X.; Piper, J.A.; Zhang, F. Lifetime-engineered NIR-II nanoparticles unlock multiplexed in vivo imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intes, X.; Ripoll, J.; Chen, Y.; Nioka, S.; Yodh, A.G.; Chance, B. In vivo continuous-wave optical breast imaging enhanced with Indocyanine Green. Med. Phys. 2003, 30, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.-C.; Hu, J.-L.; Bai, J.-W.; Zhang, G.-J. Detection of Sentinel Lymph Nodes with Near-Infrared Imaging in Malignancies. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2019, 21, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J.; Tan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Su, Y.; Cheng, T.; Shi, C. Sentinel lymph node mapping by a near-infrared fluorescent heptamethine dye. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagaya, N.; Yamazaki, R.; Nakagawa, A.; Abe, A.; Hamada, K.; Kubota, K.; Oyama, T. Intraoperative identification of sentinel lymph nodes by near-infrared fluorescence imaging in patients with breast cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2008, 195, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predina, J.D.; Keating, J.; Newton, A.; Corbett, C.; Xia, L.; Shin, M.; Frenzel Sulyok, L.; Deshpande, C.; Litzky, L.; Nie, S.; et al. A clinical trial of intraoperative near-infrared imaging to assess tumor extent and identify residual disease during anterior mediastinal tumor resection. Cancer 2019, 125, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, G.; Lee, J.C.; Robinson, J.T.; Raaz, U.; Xie, L.; Huang, N.F.; Cooke, J.P.; Dai, H. Multifunctional in vivo vascular imaging using near-infrared II fluorescence. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altinoğlu, E.I.; Russin, T.J.; Kaiser, J.M.; Barth, B.M.; Eklund, P.C.; Kester, M.; Adair, J.H. Near-infrared emitting fluorophore-doped calcium phosphate nanoparticles for in vivo imaging of human breast cancer. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 2075–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, E.H.K.; Strobl, F.; Chang, B.-J.; Preusser, F.; Preibisch, S.; McDole, K.; Fiolka, R. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, P.A. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy: A review. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011, 59, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-P.; Tang, W.-C.; Chen, P.; Chen, B.-C. Applications of Lightsheet Fluorescence Microscopy by High Numerical Aperture Detection Lens. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 8273–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjolding, L.M.; Ašmonaitė, G.; Jølck, R.I.; Andresen, T.L.; Selck, H.; Baun, A.; Sturve, J. An assessment of the importance of exposure routes to the uptake and internal localisation of fluorescent nanoparticles in zebrafish (Danio rerio), using light sheet microscopy. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Piechulek, A.; von Mikecz, A. Effect of nanoparticles on the biochemical and behavioral aging phenotype of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10695–10703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ma, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Salazar, F.; Xu, C.; Ren, F.; Qu, L.; Wu, A.M.; Dai, H. In vivo NIR-II structured-illumination light-sheet microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023888118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wan, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, Q.; Tian, Y.; Qu, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; et al. Light-sheet microscopy in the near-infrared II window. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzari, G.; Vinciguerra, D.; Balasso, A.; Nicolas, V.; Goudin, N.; Garfa-Traore, M.; Fehér, A.; Dinnyés, A.; Nicolas, J.; Couvreur, P.; et al. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy versus confocal microscopy: In quest of a suitable tool to assess drug and nanomedicine penetration into multicellular tumor spheroids. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 142, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, R.M.; Huisken, J. A guide to light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for multiscale imaging. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Qi, Y.; He, J.; Zhong, D.; Zhou, M. Recent advances in applications of nanoparticles in SERS in vivo imaging. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 13, e1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, P.L.; Dieringer, J.A.; Shah, N.C.; van Duyne, R.P. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008, 1, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokerst, J.V.; Lobovkina, T.; Zare, R.N.; Gambhir, S.S. Nanoparticle PEGylation for imaging and therapy. Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Peng, X.-H.; Ansari, D.O.; Yin-Goen, Q.; Chen, G.Z.; Shin, D.M.; Yang, L.; Young, A.N.; Wang, M.D.; Nie, S. In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Mancini, M.C.; Nie, S. Bioimaging: Second window for in vivo imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 710–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Chung, J.; Balaj, L.; Charest, A.; Bigner, D.D.; Carter, B.S.; Hochberg, F.H.; Breakefield, X.O.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. Protein typing of circulating microvesicles allows real-time monitoring of glioblastoma therapy. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1835–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Choe, C.-S.; Ahlberg, S.; Meinke, M.C.; Alexiev, U.; Lademann, J.; Darvin, M.E. Penetration of silver nanoparticles into porcine skin ex vivo using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy, Raman microscopy, and surface-enhanced Raman scattering microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015, 20, 051006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Fu, Q.; Du, W.; Zhu, R.; Ge, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Su, L.; Yang, H.; Song, J. Quantitative Assessment of Copper(II) in Wilson’s Disease Based on Photoacoustic Imaging and Ratiometric Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3402–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokerst, J.V.; Cole, A.J.; van de Sompel, D.; Gambhir, S.S. Gold nanorods for ovarian cancer detection with photoacoustic imaging and resection guidance via Raman imaging in living mice. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 10366–10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Conde, J.; Bao, C.; Chen, Y.; Curtin, J.; Cui, D. Gold nanostars for efficient in vitro and in vivo real-time SERS detection and drug delivery via plasmonic-tunable Raman/FTIR imaging. Biomaterials 2016, 106, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Jeong, S.; Park, Y.; Yim, J.; Jun, B.-H.; Kyeong, S.; Yang, J.-K.; Kim, G.; Hong, S.; Lee, L.P.; et al. Near-Infrared SERS Nanoprobes with Plasmonic Au/Ag Hollow-Shell Assemblies for In Vivo Multiplex Detection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3719–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranahan, S.M.; Willets, K.A. Super-resolution optical imaging of single-molecule SERS hot spots. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3777–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y.; He, H.; Nie, S.; Ye, J.; Lin, L. Raman-Guided Bronchoscopy: Feasibility and Detection Depth Studies Using Ex Vivo Lung Tissues and SERS Nanoparticle Tags. Photonics 2022, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, P.Z.; Mallia, R.J.; Veilleux, I.; Wilson, B.C. Widefield quantitative multiplex surface enhanced Raman scattering imaging in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2013, 18, 046011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Shen, H.; Ferrari, M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niżnik, Ł.; Noga, M.; Kobylarz, D.; Frydrych, A.; Krośniak, A.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L.; Jurowski, K. Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)-Toxicity, Safety and Green Synthesis: A Critical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Zúñiga, J.; Bruna, N.; Pérez-Donoso, J.M. Toxicity Mechanisms of Copper Nanoparticles and Copper Surfaces on Bacterial Cells and Viruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulari, E.; Gulari, E.; Tsunashima, Y.; Chu, B. Photon correlation spectroscopy of particle distributions. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 70, 3965–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudin, I.K.; Nikolaenko, G.L.; Kosov, V.I.; Agayan, V.A.; Anisimov, M.A.; Sengers, J.V. A compact photon-correlation spectrometer for research and education. Int. J. Thermophys. 1997, 18, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Yeap, S.P.; Che, H.X.; Low, S.C. Characterization of magnetic nanoparticle by dynamic light scattering. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Yang, D.; Kanaev, A. Dynamic Light Scattering: A Powerful Tool for In Situ Nanoparticle Sizing. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balog, S.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L.; Monnier, C.A.; Obiols-Rabasa, M.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Schurtenberger, P.; Petri-Fink, A. Characterizing nanoparticles in complex biological media and physiological fluids with depolarized dynamic light scattering. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 5991–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhirde, A.A.; Hassan, S.A.; Harr, E.; Chen, X. Role of Albumin in the Formation and Stabilization of Nanoparticle Aggregates in Serum Studied by Continuous Photon Correlation Spectroscopy and Multiscale Computer Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C Nanomater. Interfaces 2014, 118, 16199–16208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseker, W.; Hruszkewycz, S.O.; Lehmkühler, F.; Walther, M.; Schulte-Schrepping, H.; Lee, S.; Osaka, T.; Strüder, L.; Hartmann, R.; Sikorski, M.; et al. Towards ultrafast dynamics with split-pulse X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy at free electron laser sources. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, F.; Dallari, F.; Westermeier, F.; Wieland, D.C.F.; Parak, W.J.; Lehmkühler, F.; Schulz, F. The dynamics of PEG-coated nanoparticles in concentrated protein solutions up to the molecular crowding range. Aggregate 2024, 5, e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Sun, X.; Schulz, F.; Sanchez-Cano, C.; Feliu, N.; Westermeier, F.; Parak, W.J. X-Ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy Towards Measuring Nanoparticle Diameters in Biological Environments Allowing for the In Situ Analysis of their Bio-Nano Interface. Small 2022, 18, e2201324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Cui, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Song, H.; Tian, F.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Tai, R.; et al. Live Monitoring of Nanoparticle Aggregation and Sedimentation in Biological Fluids Using X-ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 45429–45437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.E.P.; Picco, A.S.; Galdino, F.E.; de Burgos Martins de Azevedo, M.; Cathcarth, M.; Passos, A.R.; Cardoso, M.B. Distinguishing Protein Corona from Nanoparticle Aggregate Formation in Complex Biological Media Using X-ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 13293–13299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, E.L. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: Past, present, future. Biophys. J. 2011, 101, 2855–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.V.; Wakefield, D.L.; Holowka, D.A.; Craighead, H.G.; Baird, B.A. Near-field fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy on planar membranes. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 7392–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S.; Huppertsberg, A.; Klefenz, A.; Kaps, L.; Mailänder, V.; Schuppan, D.; Butt, H.-J.; Nuhn, L.; Koynov, K. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy Monitors the Fate of Degradable Nanocarriers in the Blood Stream. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negwer, I.; Best, A.; Schinnerer, M.; Schäfer, O.; Capeloa, L.; Wagner, M.; Schmidt, M.; Mailänder, V.; Helm, M.; Barz, M.; et al. Monitoring drug nanocarriers in human blood by near-infrared fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Sompol, P.; Brandon, J.A.; Norris, C.M.; Wilkop, T.; Johnson, L.A.; Richards, C.I. In Vivo Single-Molecule Detection of Nanoparticles for Multiphoton Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy to Quantify Cerebral Blood Flow. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 6135–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liisberg, M.B.; Nolt, G.L.; Fu, X.; Cerretani, C.; Li, L.; Johnson, L.A.; Vosch, T.; Richards, C.I. DNA-AgNC Loaded Liposomes for Measuring Cerebral Blood Flow Using Two-Photon Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 12862–12874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitschke, M.; Prior, R.; Haupt, M.; Riesner, D. Detection of single amyloid beta-protein aggregates in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s patients by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 832–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, O.; Bonnet, G. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: The technique and its applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2002, 65, 251–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.J.; Bouman, C.; Carmignato, S.; Cnudde, V.; Grimaldi, D.; Hagen, C.K.; Maire, E.; Manley, M.; Du Plessis, A.; Stock, S.R. X-ray computed tomography. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, E. Computed Tomography: Physical Principles and Recent Technical Advances. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2010, 41, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, L.W. Principles of CT: Multislice CT. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2008, 36, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Y.-N.; Wang, Q.; Qi, X.-H.; Shi, G.-F.; Jia, L.-T.; Wang, X.-M.; Shi, J.-B.; Liu, F.-Y.; Wang, L.-J.; et al. A comparison of the use of contrast media with different iodine concentrations for enhanced computed tomography. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1141135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.S.; Khalatbari, S.; Cohan, R.H.; Dillman, J.R.; Myles, J.D.; Ellis, J.H. Contrast material-induced nephrotoxicity and intravenous low-osmolality iodinated contrast material: Risk stratification by using estimated glomerular filtration rate. Radiology 2013, 268, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, T.; Hupfer, M.; Brauweiler, R.; Eisa, F.; Kalender, W.A. Potential of high-Z contrast agents in clinical contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 6469–6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusic, H.; Grinstaff, M.W. X-ray-computed tomography contrast agents. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1641–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosolski, Z.; Villamizar, C.A.; Rendon, D.; Paldino, M.J.; Milewicz, D.M.; Ghaghada, K.B.; Annapragada, A.V. Ultra High-Resolution In vivo Computed Tomography Imaging of Mouse Cerebrovasculature Using a Long Circulating Blood Pool Contrast Agent. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilo, M.; Reuveni, T.; Motiei, M.; Popovtzer, R. Nanoparticles as computed tomography contrast agents: Current status and future perspectives. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meir, R.; Shamalov, K.; Betzer, O.; Motiei, M.; Horovitz-Fried, M.; Yehuda, R.; Popovtzer, A.; Popovtzer, R.; Cohen, C.J. Nanomedicine for Cancer Immunotherapy: Tracking Cancer-Specific T-Cells in Vivo with Gold Nanoparticles and CT Imaging. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6363–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, S.; Hix, J.M.L.; Wiewiora, K.A.; Volk, M.C.; Kenyon, E.; Shuboni-Mulligan, D.D.; Blanco-Fernandez, B.; Kiupel, M.; Thomas, J.; Sempere, L.F.; et al. Tantalum oxide nanoparticles as versatile contrast agents for X-ray computed tomography. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 7720–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, W.; Nicholson, A.I.; Zentgraf, H.; Semmler, W.; Bartling, S. Anti-CD4-targeted gold nanoparticles induce specific contrast enhancement of peripheral lymph nodes in X-ray computed tomography of live mice. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2318–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, T.; Motiei, M.; Romman, Z.; Popovtzer, A.; Popovtzer, R. Targeted gold nanoparticles enable molecular CT imaging of cancer: An in vivo study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 2859–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singnurkar, A.; Poon, R.; Metser, U. Comparison of 18F-FDG-PET/CT and 18F-FDG-PET/MR imaging in oncology: A systematic review. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2017, 31, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, S.; Angus, G.; Patel, B.N.; Pareek, A.; Davidzon, G.; Long, J.; Dunnmon, J.; Lungren, M.P. Multi-task weak supervision enables anatomically-resolved abnormality detection in whole-body FDG-PET/CT. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varani, M.; Bentivoglio, V.; Lauri, C.; Ranieri, D.; Signore, A. Methods for Radiolabelling Nanoparticles: SPECT Use (Part 1). Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhao, T.; Wang, C.; Nham, K.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Hao, G.; Ge, W.-P.; Sun, X.; et al. PET imaging of occult tumours by temporal integration of tumour-acidosis signals from pH-sensitive 64Cu-labelled polymers. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.D.; Wang, L.Z.; Wilson, B.K.; McManus, S.A.; Jumai’an, J.; Padakanti, P.K.; Alavi, A.; Mach, R.H.; Prud’homme, R.K. Copper Loading of Preformed Nanoparticles for PET-Imaging Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 3191–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, M.A.; Shaffer, T.M.; Harmsen, S.; Tschaharganeh, D.-F.; Huang, C.-H.; Lowe, S.W.; Drain, C.M.; Kircher, M.F. Chelator-Free Radiolabeling of SERRS Nanoparticles for Whole-Body PET and Intraoperative Raman Imaging. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3068–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Medina, C.; Abdel-Atti, D.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fayad, Z.A.; Lewis, J.S.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Reiner, T. Nanoreporter PET predicts the efficacy of anti-cancer nanotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivoglio, V.; Varani, M.; Lauri, C.; Ranieri, D.; Signore, A. Methods for Radiolabelling Nanoparticles: PET Use (Part 2). Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.D.; Bhandary, S. Nano-Revolution: Harnessing Silica Nanoparticles for Next-Generation Cancer Therapeutics. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 17, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjua, T.I.; Cao, Y.; Yu, C.; Popat, A. Clinical translation of silica nanoparticles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1072–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, R.; Goel, S.; Dash, A.; Cai, W. Radiolabeled inorganic nanoparticles for positron emission tomography imaging of cancer: An overview. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2017, 61, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Chen, L.; Hu, J.; Yu, C.; Yin, J. Radiolabelled nanomaterials for diagnostic and therapeutic applications in hepatocellular carcinoma and other liver diseases. Precis. Med. Eng. 2025, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.; Penate-Medina, O.; Zanzonico, P.B.; Carvajal, R.D.; Mohan, P.; Ye, Y.; Humm, J.; Gönen, M.; Kalaigian, H.; Schöder, H.; et al. Clinical translation of an ultrasmall inorganic optical-PET imaging nanoparticle probe. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 260ra149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, A.S.; Jokerst, J.V.; Ghanouni, P.; Campbell, J.L.; Mittra, E.; Gambhir, S.S. Clinically Approved Nanoparticle Imaging Agents. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1833–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Ma, K.; Madajewski, B.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, L.; Rickert, K.; Marelli, M.; Yoo, B.; Turker, M.Z.; Overholtzer, M.; et al. Ultrasmall targeted nanoparticles with engineered antibody fragments for imaging detection of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, E.C.; Skubal, M.; Mc Larney, B.; Causa-Andrieu, P.; Das, S.; Sawan, P.; Araji, A.; Riedl, C.; Vyas, K.; Tuch, D.; et al. Prospective testing of clinical Cerenkov luminescence imaging against standard-of-care nuclear imaging for tumour location. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarrocchi, E.; Belcari, N. Cerenkov luminescence imaging: Physics principles and potential applications in biomedical sciences. EJNMMI Phys. 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.; Germanos, M.S.; Li, C.; Mitchell, G.S.; Cherry, S.R.; Silva, M.D. Optical imaging of Cerenkov light generation from positron-emitting radiotracers. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009, 54, N355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, E.C.; Shaffer, T.M.; Grimm, J. Nanoparticles and radiotracers: Advances toward radionanomedicine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 8, 872–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, X.; Guo, J.; Zhu, W.; Ding, Y.; Niu, G.; Wang, A.; Kiesewetter, D.O.; Wang, Z.L.; Sun, S.; et al. Self-illuminating 64Cu-doped CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals for in vivo tumor imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1706–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozolmez, N.; Silindir-Gunay, M. Medical applications of Cerenkov radiation and nanomedicine: An overview. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 4387–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorek, D.L.J.; Ogirala, A.; Beattie, B.J.; Grimm, J. Quantitative imaging of disease signatures through radioactive decay signal conversion. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Larney, B.E.; Zhang, Q.; Pratt, E.C.; Skubal, M.; Isaac, E.; Hsu, H.-T.; Ogirala, A.; Grimm, J. Detection of Shortwave-Infrared Cerenkov Luminescence from Medical Isotopes. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushie, M.J.; Pickering, I.J.; Korbas, M.; Hackett, M.J.; George, G.N. Elemental and chemically specific X-ray fluorescence imaging of biological systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 8499–8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, K.; Guazzoni, C.; Castoldi, A.; Gibson, A.P.; Royle, G.J. An x-ray fluorescence imaging system for gold nanoparticle detection. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, 7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Pratx, G.; Bazalova, M.; Meng, B.; Qian, J.; Xing, L. First demonstration of multiplexed X-ray fluorescence computed tomography (XFCT) imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2013, 32, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Bazalova-Carter, M.; Fahrig, R.; Xing, L. Optimized Detector Angular Configuration Increases the Sensitivity of X-ray Fluorescence Computed Tomography (XFCT). IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, G.M.; Vogt, C.; Li, Y.; Shaker, K.; Brodin, B.; Svenda, M.; Hertz, H.M.; Toprak, M.S. Optical and X-ray Fluorescent Nanoparticles for Dual Mode Bioimaging. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 5077–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.C.; Vogt, C.; Vågberg, W.; Toprak, M.S.; Dzieran, J.; Arsenian-Henriksson, M.; Hertz, H.M. High-spatial-resolution x-ray fluorescence tomography with spectrally matched nanoparticles. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 164001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staufer, T.; Grüner, F. Review of Development and Recent Advances in Biomedical X-ray Fluorescence Imaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körnig, C.; Staufer, T.; Schmutzler, O.; Bedke, T.; Machicote, A.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Gargioni, E.; Feliu, N.; Parak, W.J.; et al. In-situ x-ray fluorescence imaging of the endogenous iodine distribution in murine thyroids. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chubarov, V.M.; Pashkova, G.V.; Maltsev, A.S.; Mukhamedova, M.M.; Statkus, M.A.; Revenko, A.G. Possibilities and Limitations of Various X-ray Fluorescence Techniques in Studying the Chemical Composition of Ancient Ceramics. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 79, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.M.; Hare, D.J.; James, S.A.; de Jonge, M.D.; McColl, G. Radiation Dose Limits for Bioanalytical X-ray Fluorescence Microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 12168–12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proskurnin, M.A.; Zhidkova, T.V.; Volkov, D.S.; Sarimollaoglu, M.; Galanzha, E.I.; Mock, D.; Nedosekin, D.A.; Zharov, V.P. In vivo multispectral photoacoustic and photothermal flow cytometry with multicolor dyes: A potential for real-time assessment of circulation, dye-cell interaction, and blood volume. Cytom. A 2011, 79, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipkins, D.A.; Wei, X.; Wu, J.W.; Runnels, J.M.; Côté, D.; Means, T.K.; Luster, A.D.; Scadden, D.T.; Lin, C.P. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature 2005, 435, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Suo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ding, N.; Pang, K.; Xie, C.; Weng, X.; Tian, M.; He, H.; et al. In vivo flow cytometry reveals a circadian rhythm of circulating tumor cells. Light Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Pang, K.; Song, Q.; Suo, Y.; He, H.; Weng, X.; Gao, X.; Wei, X. Noninvasive monitoring of nanoparticle clearance and aggregation in blood circulation by in vivo flow cytometry. J. Control. Release 2018, 278, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y.; Gu, Z.; Wei, X. Advances of In Vivo Flow Cytometry on Cancer Studies. Cytom. A 2020, 97, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanzha, E.I.; Shashkov, E.V.; Kelly, T.; Kim, J.-W.; Yang, L.; Zharov, V.P. In vivo magnetic enrichment and multiplex photoacoustic detection of circulating tumour cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerton, R.F. Physical Principles of Electron Microscopy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-39876-1. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.B.; Carter, C.B. (Eds.) The Transmission Electron Microscope. In Transmission Electron Microscopy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-0-306-45324-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.M.; Spence, J.C.H. Advanced Transmission Electron Microscopy; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4939-6605-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra, M.J.; Reuss, L.E. (Eds.) Scanning Electron Microscopy. In Biological Electron Microscopy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 357–383. ISBN 978-1-4613-4856-6. [Google Scholar]

- Franken, L.E.; Grünewald, K.; Boekema, E.J.; Stuart, M.C.A. A Technical Introduction to Transmission Electron Microscopy for Soft-Matter: Imaging, Possibilities, Choices, and Technical Developments. Small 2020, 16, e1906198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.E.; Li, H.; Bessette, S.; Gauvin, R.; Patience, G.S.; Dummer, N.F. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Scanning electron microscopy and X-ray ultra-microscopy—SEM and XuM. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 100, 3145–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.I.; Newbury, D.E.; Michael, J.R.; Ritchie, N.W.M.; Scott, J.H.J.; Joy, D.C. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4939-6674-5. [Google Scholar]

- Egerton, R.F.; Watanabe, M. Spatial resolution in transmission electron microscopy. Micron 2022, 160, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Mak, K.Y.; Shi, J.; Koon, H.K.; Leung, C.H.; Wong, C.M.; Leung, C.W.; Mak, C.S.K.; Chan, N.M.M.; Zhong, W.; et al. Comparative in vitro cytotoxicity study on uncoated magnetic nanoparticles: Effects on cell viability, cell morphology, and cellular uptake. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 9010–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cambria, M.T.; Villaggio, G.; Laudani, S.; Pulvirenti, L.; Federico, C.; Saccone, S.; Condorelli, G.G.; Sinatra, F. The Interplay between Fe3O4 Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles, Sodium Butyrate, and Folic Acid for Intracellular Transport. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielańczyk, Ł.; Matysiak, N.; Klymenko, O.; Wojnicz, R. Transmission Electron Microscopy of Biological Samples. In The Transmission Electron Microscope—Theory and Applications; Maaz, K., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-953-51-2150-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xiao, M.; Quezada-Renteria, J.A.; Hou, Z.; Hoek, E.M.V. Sample preparation matters: Scanning electron microscopic characterization of polymeric membranes. J. Membr. Sci. Lett. 2024, 4, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusman, Y.; Ng, S.C.; Abu Osman, N.A. Investigation of CPD and HMDS sample preparation techniques for cervical cells in developing computer-aided screening system based on FE-SEM/EDX. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 289817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.I.; Abrams, G.A.; Bertics, P.J.; Murphy, C.J.; Nealey, P.F. Epithelial contact guidance on well-defined micro- and nanostructured substrates. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting-Beall, H.P.; Zhelev, D.V.; Hochmuth, R.M. Comparison of different drying procedures for scanning electron microscopy using human leukocytes. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1995, 32, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahemanesh, K.; Mehdizadeh Kashi, A.; Chaichian, S.; Joghataei, M.T.; Moradi, F.; Tavangar, S.M.; Mousavi Najafabadi, A.S.; Lotfibakhshaiesh, N.; Pour Beyranvand, S.; Fazel Anvari-Yazdi, A.; et al. How to Prepare Biological Samples and Live Tissues for Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). GMJ Galen Med. J. 2014, 3, e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.; Soroka, Y.; Frušić-Zlotkin, M.; Popov, I.; Kohen, R. High resolution SEM imaging of gold nanoparticles in cells and tissues. J. Microsc. 2014, 256, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margus, H.; Padari, K.; Pooga, M. Insights into cell entry and intracellular trafficking of peptide and protein drugs provided by electron microscopy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifarth, M.; Hoeppener, S.; Schubert, U.S. Uptake and Intracellular Fate of Engineered Nanoparticles in Mammalian Cells: Capabilities and Limitations of Transmission Electron Microscopy-Polymer-Based Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1703704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhwani, S.; Syed, A.M.; Ngai, J.; Kingston, B.R.; Maiorino, L.; Rothschild, J.; MacMillan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Rajesh, N.U.; Hoang, T.; et al. The entry of nanoparticles into solid tumours. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, M.J.; Smith, I.; Parker, I.; Bootman, M.D. Fluorescence microscopy. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2014, 2014, pdb.top071795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, W.M.; Obara, C.J. Advances in Confocal Microscopy and Selected Applications. In Confocal Microscopy; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2304, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladjenovic, S.M.; Chandok, I.S.; Darbandi, A.; Nguyen, L.N.M.; Stordy, B.; Zhen, M.; Chan, W.C.W. 3D electron microscopy for analyzing nanoparticles in the tumor endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2406331121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göttfert, F.; Wurm, C.A.; Mueller, V.; Berning, S.; Cordes, V.C.; Honigmann, A.; Hell, S.W. Coaligned dual-channel STED nanoscopy and molecular diffusion analysis at 20 nm resolution. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, L01–L03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.; Wildanger, D.; Medda, R.; Punge, A.; Rizzoli, S.O.; Donnert, G.; Hell, S.W. Dual-color STED microscopy at 30-nm focal-plane resolution. Small 2008, 4, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicidomini, G.; Bianchini, P.; Diaspro, A. STED super-resolved microscopy. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Rai, N.; Verma, A.; Gautam, V. Microscopy based methods for characterization, drug delivery, and understanding the dynamics of nanoparticles. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 138–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Cao, H.; Lin, D.; Yu, B.; Qu, J. Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles for biological super-resolution fluorescence imaging. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Elgawish, M.S.; Shim, S.-H. Bleaching-Resistant Super-Resolution Fluorescence Microscopy. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; Carton, F.; Marengo, A.; Berlier, G.; Stella, B.; Arpicco, S.; Malatesta, M. Fluorescence and electron microscopy to visualize the intracellular fate of nanoparticles for drug delivery. Eur. J. Histochem. 2016, 60, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeckmans, K.; Buyens, K.; Naeye, B.; Vercauteren, D.; Deschout, H.; Raemdonck, K.; Remaut, K.; Sanders, N.N.; Demeester, J.; de Smedt, S.C. Advanced fluorescence microscopy methods illuminate the transfection pathway of nucleic acid nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2010, 148, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimold, I.; Domke, D.; Bender, J.; Seyfried, C.A.; Radunz, H.-E.; Fricker, G. Delivery of nanoparticles to the brain detected by fluorescence microscopy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 70, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhukova, V.; Osipova, N.; Semyonkin, A.; Malinovskaya, J.; Melnikov, P.; Valikhov, M.; Porozov, Y.; Solovev, Y.; Kuliaev, P.; Zhang, E.; et al. Fluorescently Labeled PLGA Nanoparticles for Visualization In Vitro and In Vivo: The Importance of Dye Properties. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F. Noninvasive in vivo microscopy of single neutrophils in the mouse brain via NIR-II fluorescent nanomaterials. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 2386–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, W.R.; Williams, R.M.; Webb, W.W. Nonlinear magic: Multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifu, N.; Yan, L.; Zhang, H.; Zebibula, A.; Zhu, Z.; Xi, W.; Roe, A.W.; Xu, B.; Tian, W.; Qian, J. Organic dye doped nanoparticles with NIR emission and biocompatibility for ultra-deep in vivo two-photon microscopy under 1040 nm femtosecond excitation. Dye. Pigment. 2017, 143, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, S.; Eremina, O.E.; Mouchawar, A.; Fernando, A.; Edmondson, E.; Stern, S.; Marks, C.; Zavaleta, C. Multiphoton Luminescence Imaging: A Label-Free Tool for Visualizing the Long-Term Fate of Gold Nanoparticles in Tissue. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 29286–29300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzel, S.; Hermann, S.; Kugel, Y.; Sellner, S.; Uhl, B.; Hirn, S.; Krombach, F.; Rehberg, M. Multiphoton Microscopy of Nonfluorescent Nanoparticles In Vitro and In Vivo. Small 2016, 12, 3245–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wang, D.; Cai, F.-H.; Xi, W.; Peng, L.; Zhu, Z.-F.; He, H.; Hu, M.-L.; He, S. Observation of Multiphoton-Induced Fluorescence from Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles and Applications in In Vivo Functional Bioimaging. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 10722–10727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priwitaningrum, D.L.; Pednekar, K.; Gabriël, A.V.; Varela-Moreira, A.A.; Le Gac, S.; Vellekoop, I.; Storm, G.; Hennink, W.E.; Prakash, J. Evaluation of paclitaxel-loaded polymeric nanoparticles in 3D tumor model: Impact of tumor stroma on penetration and efficacy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 1470–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Y.H.; Holmes, A.; Haridass, I.N.; Sanchez, W.Y.; Studier, H.; Grice, J.E.; Benson, H.A.E.; Roberts, M.S. Support for the Safe Use of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Sunscreens: Lack of Skin Penetration or Cellular Toxicity after Repeated Application in Volunteers. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvin, M.E.; König, K.; Kellner-Hoefer, M.; Breunig, H.G.; Werncke, W.; Meinke, M.C.; Patzelt, A.; Sterry, W.; Lademann, J. Safety assessment by multiphoton fluorescence/second harmonic generation/hyper-Rayleigh scattering tomography of ZnO nanoparticles used in cosmetic products. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 25, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiev, U.; Volz, P.; Boreham, A.; Brodwolf, R. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy (FLIM) as an analytical tool in skin nanomedicine. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 116, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhling, K.; French, P.M.W.; Phillips, D. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2005, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skala, M.C.; Riching, K.M.; Bird, D.K.; Gendron-Fitzpatrick, A.; Eickhoff, J.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Keely, P.J.; Ramanujam, N. In vivo multiphoton fluorescence lifetime imaging of protein-bound and free nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in normal and precancerous epithelia. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007, 12, 024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, M.A.; Sutin, J.; Wu, W.; Fu, B.; Uhlirova, H.; Devor, A.; Boas, D.A.; Sakadžić, S. Fluorescence lifetime microscopy of NADH distinguishes alterations in cerebral metabolism in vivo. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 2368–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, C.; Martin, M.; Roldan, M.; Talavera, E.M.; Orte, A.; Ruedas-Rama, M.J. Intracellular Zn(2+) detection with quantum dot-based FLIM nanosensors. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 16964–16967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Hall, D.J.; Qin, Z.; Anglin, E.; Joo, J.; Mooney, D.J.; Howell, S.B.; Sailor, M.J. In vivo time-gated fluorescence imaging with biodegradable luminescent porous silicon nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Liu, X.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Ruoslahti, E.; Nam, Y.; Sailor, M.J. Gated Luminescence Imaging of Silicon Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6233–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, P.; Yang, H.; Liang, S.; Chen, D.; Xu, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; et al. In Vivo NIR-II Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Whole-Body Vascular Using High Quantum Yield Lanthanide-Doped Nanoparticles. Small 2023, 19, e2300392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdasaryan, A.; Dai, H. Molecular Gold Nanoclusters for Advanced NIR-II Bioimaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 5195–5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessibl, F.J. Advances in atomic force microscopy. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 949–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xiong, F.; Li, X.; Xiang, B.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Guo, C.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; et al. Application of atomic force microscopy in cancer research. J. Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, R.; Picotto, G.B.; Ribotta, L. AFM Measurements and Tip Characterization of Nanoparticles with Different Shapes. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2022, 5, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrgiotakis, G.; Blattmann, C.O.; Demokritou, P. Real-Time Nanoparticle-Cell Interactions in Physiological Media by Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamprou, D.A.; Venkatpurwar, V.; Kumar, M.N.V.R. Atomic force microscopy images label-free, drug encapsulated nanoparticles in vivo and detects difference in tissue mechanical properties of treated and untreated: A tip for nanotoxicology. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Batiuskaite, D.; Bruzaite, I.; Snitka, V.; Ramanavicius, A. Assessment of TiO2 Nanoparticle Impact on Surface Morphology of Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells. Materials 2022, 15, 4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, P.; Cognet, L.; Lounis, B. Photothermal microscopy: Optical detection of small absorbers in scattering environments. J. Microsc. 2014, 254, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berciaud, S.; Cognet, L.; Blab, G.A.; Lounis, B. Photothermal heterodyne imaging of individual nonfluorescent nanoclusters and nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 257402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedosekin, D.A.; Foster, S.; Nima, Z.A.; Biris, A.S.; Galanzha, E.I.; Zharov, V.P. Photothermal confocal multicolor microscopy of nanoparticles and nanodrugs in live cells. Drug Metab. Rev. 2015, 47, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijeesh, M.M.; Shakhi, P.K.; Arunkarthick, S.; Varier, G.K.; Nandakumar, P. Confocal imaging of single BaTiO3 nanoparticles by two-photon photothermal microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, L.K.; Taylor, A.; Cesbron, Y.; Murray, P.; Lévy, R. Photothermal microscopy of the core of dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles during cell uptake. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5961–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibu, E.S.; Varkentina, N.; Cognet, L.; Lounis, B. Small Gold Nanorods with Tunable Absorption for Photothermal Microscopy in Cells. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1600280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cognet, L.; Tardin, C.; Boyer, D.; Choquet, D.; Tamarat, P.; Lounis, B. Single metallic nanoparticle imaging for protein detection in cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11350–11355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Kwak, M.; Kwon, I.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.Y. Quantification of cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles via scattering intensity changes in flow cytometry. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 3558–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, R.M.; Boyes, W.K. Detection of Silver and TiO2 Nanoparticles in Cells by Flow Cytometry. In Nanoparticles in Biology and Medicine; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2118, pp. 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, M.K.; Yang, N.; Yoon, T.H. Flow Cytometry-Based Quantification of Cellular Au Nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenović, D.; Brealey, J.; Peacock, B.; Koort, K.; Zarovni, N. Quantitative fluorescent nanoparticle tracking analysis and nano-flow cytometry enable advanced characterization of single extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Biol. 2025, 4, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottstein, C.; Wu, G.; Wong, B.J.; Zasadzinski, J.A. Precise quantification of nanoparticle internalization. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4933–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Flores, M. Fighting Cancer Resistance: An Overview. In Cancer Cell Signaling; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2174, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Y.; Xu, T.; Lv, D.; Yu, P.; Xu, J.; Che, L.; Das, A.; Tigges, J.; Toxavidis, V.; Ghiran, I.; et al. Exercise-induced circulating extracellular vesicles protect against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, G.C.; Chen, Y.Q.; Martinez, E.; Tang, V.A.; Renner, T.M.; Langlois, M.-A.; Gulnik, S. A Novel Semiconductor-Based Flow Cytometer with Enhanced Light-Scatter Sensitivity for the Analysis of Biological Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, E.; Kapinsky, M.; Larbi, A. An Update on Flow Cytometry Analysis of Hematological Malignancies: Focus on Standardization. Cancers 2025, 17, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowski-Daspit, A.S.; Bracaglia, L.G.; Eaton, D.A.; Richfield, O.; Binns, T.C.; Albert, C.; Gould, J.; Mortlock, R.D.; Egan, M.E.; Pober, J.S.; et al. Enhancing in vivo cell and tissue targeting by modulation of polymer nanoparticles and macrophage decoys. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, H.S.; Zhang, J.; Donohue, D.; Unnithan, R.; Cedrone, E.; Xu, J.; Vermilya, A.; Malys, T.; Clogston, J.D.; Dobrovolskaia, M.A. Multicolor flow cytometry-based immunophenotyping for preclinical characterization of nanotechnology-based formulations: An insight into structure activity relationship and nanoparticle biocompatibility profiles. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1126012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchisio, M.; Simeone, P.; Bologna, G.; Ercolino, E.; Pierdomenico, L.; Pieragostino, D.; Ventrella, A.; Antonini, F.; Del Zotto, G.; Vergara, D.; et al. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Circulating Extracellular Vesicle Subtypes from Fresh Peripheral Blood Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korangath, P.; Barnett, J.D.; Sharma, A.; Henderson, E.T.; Stewart, J.; Yu, S.-H.; Kandala, S.K.; Yang, C.-T.; Caserto, J.S.; Hedayati, M.; et al. Nanoparticle interactions with immune cells dominate tumor retention and induce T cell-mediated tumor suppression in models of breast cancer. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.B.; Kromann, E.B. Pitfalls and opportunities in quantitative fluorescence-based nanomedicine studies—A commentary. J. Control. Release 2021, 335, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Wang, J.; Ping, Q.; Yeo, Y. Quantitative Assessment of Nanoparticle Biodistribution by Fluorescence Imaging, Revisited. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6458–6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelepukin, I.V.; Yaremenko, A.V.; Petersen, E.V.; Deyev, S.M.; Cherkasov, V.R.; Nikitin, P.I.; Nikitin, M.P. Magnetometry based method for investigation of nanoparticle clearance from circulation in a liver perfusion model. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, D.R.; Baranov, V.I.; Ornatsky, O.I.; Antonov, A.; Kinach, R.; Lou, X.; Pavlov, S.; Vorobiev, S.; Dick, J.E.; Tanner, S.D. Mass cytometry: Technique for real time single cell multitarget immunoassay based on inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 6813–6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, R.K.; Utz, P.J. CyTOF-the next generation of cell detection. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011, 7, 502–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]