Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification Mechanisms for Bioelectronic Detection: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Underlying Mechanisms of Polymer-Mediated Amplification Strategies

2.1. Molecular Structure–Property Relationships in Signal Amplification

2.2. Charge-Transport Optimization in Polymeric Amplification Systems

2.3. Energy-Transfer Enhancement Through Polymer-Assisted Optical Processes

2.4. Interfacial Stability and Antifouling Regulation by Polymeric Materials

3. Typical Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification Strategies

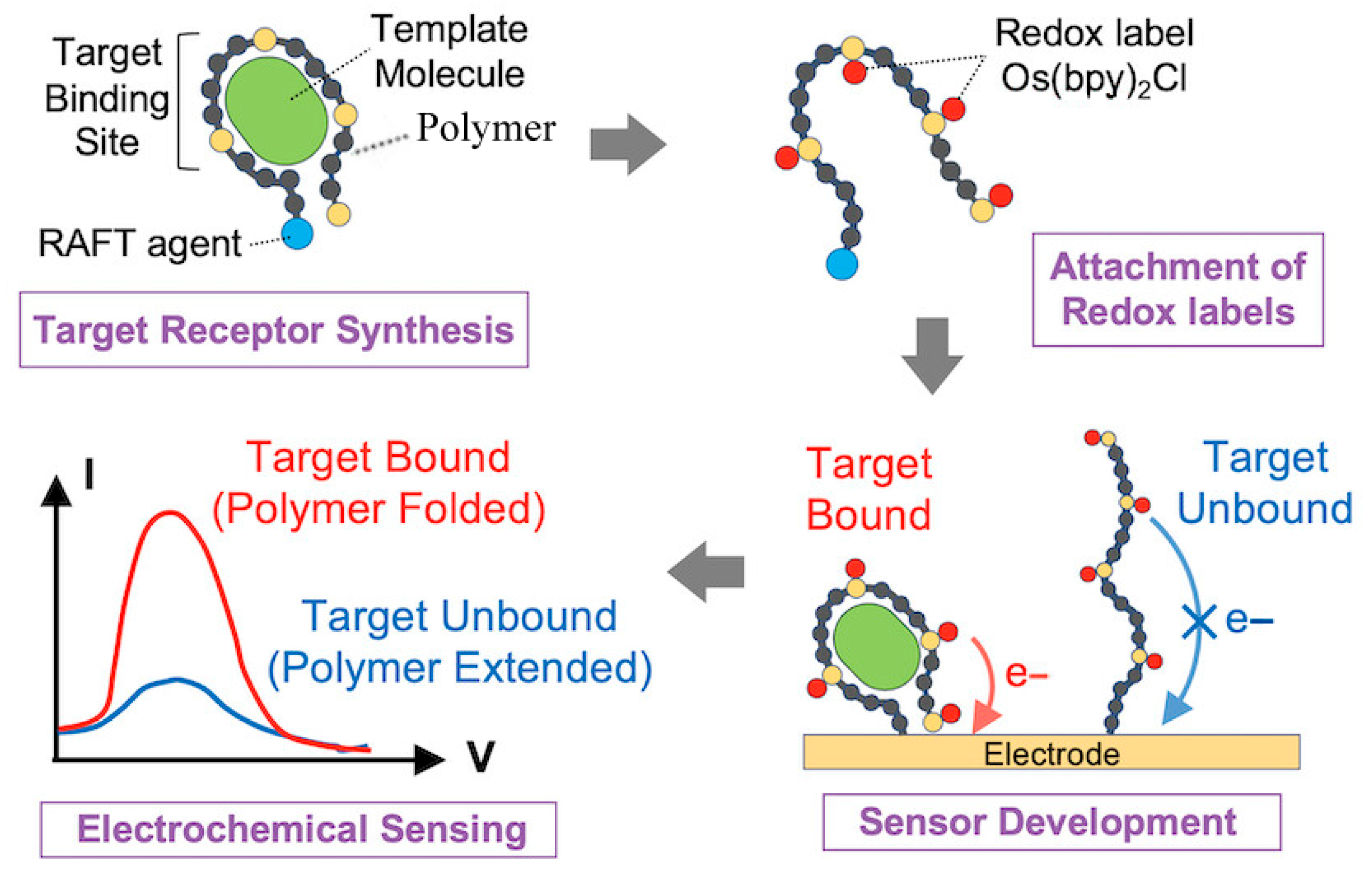

3.1. Signal Amplification Mediated by MIPs

3.2. Functional Polymer–Nanocomposite Platforms for Multimodal Signal Amplification

3.3. Polymeric Hydrogels and Three-Dimensional Porous Networks

3.4. Functional Biointerfaces Based on Conducting Polymers

3.5. Adaptive and Stimuli-Responsive Polymers

4. Applications of Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification in Bioelectronic Sensing

4.1. Medical Diagnosis and Health Monitoring

4.2. Food Safety Monitoring

4.3. Environmental Monitoring

5. Conclusions and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inês, A.; Cosme, F. Biosensors for Detecting Food Contaminants—An Overview. Processes 2025, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Fan, C.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; Shi, L.; Li, X.; et al. Recent Advances of Fluorescent Biosensors Based on Cyclic Signal Amplification Technology in Biomedical Detection. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zuo, X.; Carpenter, M.D.; Verduzco, R.; Ajo-Franklin, C.M. Microbial Bioelectronic Sensors for Environmental Monitoring. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2024, 3, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dkhar, D.S.; Kumari, R.; Mahapatra, S.; Divya; Kumar, R.; Tripathi, T.; Chandra, P. Antibody-Receptor Bioengineering and Its Implications in Designing Bioelectronic Devices. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Najeeb, J.; Asim Ali, M.; Aslam, M.F.; Raza, A. Biosensors: Their Fundamentals, Designs, Types and Most Recent Impactful Applications: A Review. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaster, R.S.; Hall, D.A.; Nielsen, C.H.; Osterfeld, S.J.; Yu, H.; Mach, K.E.; Wilson, R.J.; Murmann, B.; Liao, J.C.; Gambhir, S.S.; et al. Matrix-Insensitive Protein Assays Push the Limits of Biosensors in Medicine. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Agrawal, M.; Srivastava, A. Signal Amplification Strategies in Electrochemical Biosensors via Antibody Immobilization and Nanomaterial-Based Transducers. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 8864–8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.-Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Ma, X.; Ding, S.-N. Bipolar Electrochemiluminescence Sensors: From Signal Amplification Strategies to Sensing Formats. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, B.; Ma, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Hu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, D. A Microfluidic-Based Chemiluminescence Biosensor for Sensitive Multiplex Detection of Exosomal microRNAs Based on Hybridization Chain Reaction. Talanta 2025, 281, 126838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Gao, D. Recent Advances in Aptamer-Based Microfluidic Biosensors for the Isolation, Signal Amplification and Detection of Exosomes. Sensors 2025, 25, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Benny, L.; Cherian, A.R.; Narahari, S.Y.; Varghese, A.; Hegde, G. Electrochemical Sensors Using Conducting Polymer/Noble Metal Nanoparticle Nanocomposites for the Detection of Various Analytes: A Review. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2021, 11, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Mun, S.; Youn, J.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.K.; Choi, M.; Kang, T.J.; Pei, Q.; Yun, S. Height-Renderable Morphable Tactile Display Enabled by Programmable Modulation of Local Stiffness in Photothermally Active Polymer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Sun, J.; Liu, M.; Huang, J.; Dong, J.; Guo, Z.; Guo, Y.; Sun, X. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers-Aptamer Electrochemical Sensor Based on Dual Recognition Strategy for High Sensitivity Detection of Chloramphenicol. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, D.; Qian, R.; Jiang, Y. Polydopamine-Modified TS-1 Zeolite Framework Nanoparticles as a Matrix for the Analysis of Small Molecules by MALDI-TOF MS. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19952–19959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lv, Z.; Batool, S.; Li, M.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S. Biocompatible Material-Based Flexible Biosensors: From Materials Design to Wearable/Implantable Devices and Integrated Sensing Systems. Small 2023, 19, 2207879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettucci, O.; Matrone, G.M.; Santoro, F. Conductive Polymer-Based Bioelectronic Platforms Toward Sustainable and Biointegrated Devices: A Journey from Skin to Brain across Human Body Interfaces. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, H.; Xue, X.; Tan, F.; Ye, L. Signal Amplification in Molecular Sensing by Imprinted Polymers. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, A.B.; Haque, M.; Islam, S.M.M.; Uddin Labib, K.M.R. Nanotechnology-Enhanced Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: Recent Advancements on Processing Techniques and Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodhan, S.; Manurung, R.; Troisi, A. From Monomer Sequence to Charge Mobility in Semiconductor Polymers via Model Reduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2303234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L. Structure–Property Relationships in Amorphous Thieno[3,2-b]thiophene–Diketopyrrolopyrrole–Thiophene-Containing Polymers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 10907–10916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.; Ta, D.; Lauto, A.; Baker, C.; Daniels, J.; Wagner, P.; Wagner, K.K.; Kirby, N.; Cazorla, C.; Officer, D.L.; et al. Impact of Side Chain Extension on the Morphology and Electrochemistry of Phosphonated Poly(Ethylenedioxythiophene) Derivatives. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. The Effect of Side Chain Engineering on Conjugated Polymers in Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Bioelectronic Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 2314–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrey, T.L.; Berteau-Rainville, M.; Gonel, G.; Saska, J.; Shevchenko, N.E.; Fergerson, A.S.; Talbot, R.M.; Yacoub, N.L.; Zhang, F.; Kahn, A.; et al. Quantifying Polaron Densities in Sequentially Doped Conjugated Polymers: Exploring the Upper Limits of Molecular Doping and Conductivity. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 11234–11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Halaksa, R.; Jo, I.Y.; Ahn, H.; Gilhooly-Finn, P.A.; Lee, I.; Park, S.; Nielsen, C.B.; Yoon, M.H. Peculiar Transient Behaviors of Organic Electrochemical Transistors Governed by Ion Injection Directionality. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.D.; Snyder, G.J. Charge-Transport Model for Conducting Polymers. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, M.; Menon, R. Polymer Electronic Materials: A Review of Charge Transport. Polym. Int. 2006, 55, 1371–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Hui, N. A Low Fouling Electrochemical Biosensor Based on the Zwitterionic Polypeptide Doped Conducting Polymer PEDOT for Breast Cancer Marker BRCA1 Detection. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 136, 107595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, G. A Novel Signal Amplification Strategy Electrochemical Immunosensor for Ultra-Sensitive Determination of P53 Protein. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 137, 107647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bai, H.; Yu, W.; Gao, Z.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Huang, Y.; Lv, F.; Wang, S. Flexible Bioelectronic Device Fabricated by Conductive Polymer–Based Living Material. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Hao, Y.; Tian, X.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Shahid, M.; Iyer, P.K.; Gao, R. Aggregation and Binding-Directed FRET Modulation of Conjugated Polymer Materials for Selective and Point-of-Care Monitoring of Serum Albumins. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 10685–10694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Han, Y.; Zhou, W.; Shen, W.; Wang, Y. A FRET Based Composite Sensing Material Based on UCNPs and Rhodamine Derivative for Highly Sensitive and Selective Detection of Fe3+. J. Fluoresc. 2023, 33, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfui, M.H.; Hassan, N.; Roy, S.; Chowdhury, D.; Rahaman, M.; Chang, M.; Ghosh, N.N.; Chattopadhyay, P.K.; Maiti, D.K.; Singha, N.R. Exploring ICT-FRET in Aliphatic Electroactive Fluorescent Polymers and Fluorometric/Electrochemical/Impedimetric Sensing of Picric Acid in Aqueous and Organic Media. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 12616–12633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, W.; Ding, C.; Luo, X. Antifouling Electrochemical Biosensor Based on the Designed Functional Peptide and the Electrodeposited Conducting Polymer for CTC Analysis in Human Blood. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tang, L.; Jiang, Y. Chemical Strategies of Tailoring PEDOT:PSS for Bioelectronic Applications: Synthesis, Processing and Device Fabrication. CCS Chem. 2024, 6, 1844–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, B.D.; Fabiano, S.; Rivnay, J. Mixed Ionic–Electronic Transport in Polymers. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2021, 51, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, A.; Apetrei, C. A Review of Sensors and Biosensors Modified with Conducting Polymers and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers Used in Electrochemical Detection of Amino Acids: Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, and Tryptophan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylan, Y.; Kılıç, S.; Denizli, A. Biosensing Applications of Molecularly Imprinted-Polymer-Based Nanomaterials. Processes 2024, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilvenyte, G.; Ratautaite, V.; Boguzaite, R.; Ramanavicius, A.; Viter, R.; Ramanavicius, S. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for the Determination of Cancer Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, T.; Chu, Z.; Dempsey, E.; Jin, W. Conductive Polymer Nanocomposites: Recent Advances in the Construction of Electrochemical Biosensors. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Kumar, A.; Prasher, P.; Bhat, M.A.; Mudila, H. Unravelling the Potential of Graphene/Transition Metal Chalcogenides Nanocomposites as Electrochemical Sensors for Drug Detection: A Review. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Geng, B.; Chen, F.; Yuan, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Jia, W.; Hu, W. Triple-Network-Based Conductive Polymer Hydrogel for Soft and Elastic Bioelectronic Interfaces. SmartMat 2024, 5, e1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, D.; Santhamoorthy, M.; Kim, S.-C.; Lim, H.-R. Conductive Polymer-Based Hydrogels for Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors. Gels 2024, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wen, F.; Lai, Y.; Li, H. Conductive Hydrogel for Flexible Bioelectronic Device: Current Progress and Future Perspective. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2308974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero De Espinosa, L.; Meesorn, W.; Moatsou, D.; Weder, C. Bioinspired Polymer Systems with Stimuli-Responsive Mechanical Properties. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 12851–12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, E.A.; Maraj, J.J.; Kenney, C.; Sarles, S.A.; Rivnay, J. Droplet Polymer Bilayers for Bioelectronic Membrane Interfacing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 14391–14396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wei, X.; He, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; He, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, N. Research Progress and Emerging Directions in Stimulus Electro-Responsive Polymer Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damani, V.S.; Kayser, L.V. Stimuli-Responsive Conductive Polymers for Bioelectronics. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 4537–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, T.; Yao, Z.; Hu, T.; Ji, X.; Yao, B. Harnessing Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials for Advanced Biomedical Applications. Exploration 2025, 5, 20230133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Venkatram, R.; Singhal, R.S. Recent Advances in the Application of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) in Food Analysis. Food Control 2022, 139, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, M.; Benhawy, A.; Khalifa, R.; El Nashar, R.; Trojanowicz, M. Application of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers in the Analysis of Waters and Wastewaters. Molecules 2021, 26, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pagett, M.; Zhang, W. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Based Electrochemical Sensors and Their Recent Advances in Health Applications. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2023, 5, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Qi, X.; Wu, J.; Wan, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y. Highly Stable Electrochemical Sensing Platform for the Selective Determination of Pefloxacin in Food Samples Based on a Molecularly Imprinted-Polymer-Coated Gold Nanoparticle/Black Phosphorus Nanocomposite. Food Chem. 2024, 436, 137753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, I.; Lertanantawong, B.; Sutthibutpong, T.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Asanithi, P. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Amyloid Fibril-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for Ultrasensitive Detection of Tryptophan. Biosensors 2022, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, N.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. A Novel Self-Enhanced Electrochemiluminescence Sensor Based on PEI-CdS/Au@SiO2@RuDS and Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for the Highly Sensitive Detection of Creatinine. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 306, 127591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-R.; Gan, X.-T.; Xu, J.-J.; Pan, Q.-F.; Liu, H.; Sun, A.-L.; Shi, X.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-M. Ultrasensitive Electrochemiluminescence Sensor Based on Perovskite Quantum Dots Coated with Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for Prometryn Determination. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, G.; He, F.; Hou, S. Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemiluminescence Sensor Based on a Novel Luminol Derivative for Detection of Human Serum Albumin via Click Reaction. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, N.; Fang, Y.; Cui, B. Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemiluminescence Sensor Based on Flake-like Au@Cu:ZIF-8 Nanocomposites for Ultrasensitive Detection of Malathion. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 399, 134837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, Y. Electrochemical Sensors Based on Polyaniline Nanocomposites for Detecting Cd(II) in Wastewater. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, R.A.; Lakavath, K.; Phani Kumar, V.V.N.; Karingula, S.; Mahato, K.; Kotagiri, Y.G. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of a Porous Reduced Graphene Oxide–Polypyrrole–Gold Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanocomposite for Electrochemical Detection of Methotrexate Using a Strip Sensor. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 4472–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, S.; Liaqat, F.; Jabeen, A.; Ahmed, S. An Effective Sensing Platform Composed of Polyindole Based Ternary Nanocomposites for Electrochemical Detection of Ascorbic Acid. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 316, 129113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawaniya, S.D.; Kumar, S.; Yu, Y.; Awasthi, K. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nano-Onions/Polypyrrole Nanocomposite Based Low-Cost Flexible Sensor for Room Temperature Ammonia Detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghan-Manshadi, H.; Mazloum-Ardakani, M.; Mozaffari, S.A. A Flexible Capacity-Metric Creatinine Sensor Based on Polygon-Shape Polyvinylpyrrolidone/CuO and Fe2O3 NRDs Electrodeposited on Three-Dimensional TiO2–V2O5–Polypyrrole Nanocomposite. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 246, 115881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yu, G.; Zhai, D.; Lee, H.R.; Zhao, W.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Tee, B.C.-K.; Shi, Y.; Cui, Y.; et al. Hierarchical Nanostructured Conducting Polymer Hydrogel with High Electrochemical Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9287–9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cao, J.; Wan, R.; Feig, V.R.; Tringides, C.M.; Xu, J.; Yuk, H.; Lu, B. PEDOTs-Based Conductive Hydrogels: Design, Fabrications, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2415151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Yang, M.; Yang, T.; Xu, C.; Ye, Y.; Wu, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, B.; Wan, Y.; Luo, Z. Highly Conductive PPy–PEDOT:PSS Hybrid Hydrogel with Superior Biocompatibility for Bioelectronics Application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 25374–25382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lian, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hasebe, Y. Highly Stretchable, Adhesive and Conductive Hydrogel for Flexible and Stable Bioelectrocatalytic Sensing Layer of Enzyme-Based Amperometric Glucose Biosensor. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 163, 108882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qiao, X.; Tao, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, S.; Cai, Y.; Luo, X. A Wearable Sensor Based on Multifunctional Conductive Hydrogel for Simultaneous Accurate pH and Tyrosine Monitoring in Sweat. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 234, 115360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, W.; Guan, Q.; Lv, J.; Wang, Z.; Ding, L.; Li, C.; Saiz, E.; Hou, X. Sweat-Resistant Bioelectronic Skin Sensor. Device 2023, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Xie, H.; Liu, C.; Liao, J.; Zhao, D.; Sun, Q.; Shamshina, J.L.; Shen, X. Dual-Working-Pattern Nanosheet-Based Hydrogel Sensors for Constructing Human-Machine and Physiological-Electric Interfaces. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e14301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, B.; Xu, Q. Highly Conductive and Sensitive Acrylamide-Modified Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Polyvinyl Alcohol Composite Hydrogels for Flexible Sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 370, 115258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, G.; Xu, Z.; Tang, D.; Chen, T. Recent Progress in Bionic Skin Based on Conductive Polymer Gels. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Jin, Y.; Chen, G.; Zheng, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L. Highly Sensitive and Wearable Bionic Piezoelectric Sensor for Human Respiratory Monitoring. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2022, 345, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, P.; Hong, W.; Zhu, X.; Hao, J.; He, C.; Hou, H.; Kong, D.; Liu, T.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Arch-Inspired Flexible Dual-Mode Sensor with Ultra-High Linearity Based on Carbon Nanomaterials/Conducting Polymer Composites for Bioelectronic Monitoring and Thermal Perception. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 267, 111182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Mugo, S.M.; Zhang, Q. Responsive Microgels-Based Wearable Devices for Sensing Multiple Health Signals. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Zou, G.; Huang, J.; Ren, X.; Tian, Q.; Yu, Q.; Wang, P.; Yuan, Y.; Tang, W.; Wang, C.; et al. Water-Responsive Supercontractile Polymer Films for Bioelectronic Interfaces. Nature 2023, 624, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, C.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, S.; Su, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, M. Three Birds, One Stone: A Multifunctional POM-Based Ionic Hydrogel Integrating Strain Sensing, Fluorescent and Antibacterial Properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigolaeva, L.V.; Rudakov, N.S.; Pergushov, D.V. Polymer-Enzyme Films on Conductive Surfaces: From Surface Modification by a Dual-Stimuli-Sensitive Polymer to Design of Electrochemical Biosensors. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 11690–11702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutharani, B.; Ranganathan, P.; Chen, S.-M.; Tsai, H.-C. Temperature-Responsive Voltammetric Sensor Based on Stimuli-Sensitive Semi-Interpenetrating Polymer Network Conductive Microgels for Reversible Switch Detection of Nitrogen Mustard Analog Chlorambucil (LeukeranTM). Electrochim. Acta 2021, 374, 137866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian-Alam, L.; Andrade, A.; Song, E. Electrochemical Detection of Glutamate and Histamine Using Redox-Labeled Stimuli-Responsive Polymer as a Synthetic Target Receptor. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 5630–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Shi, G.; Zhu, A. Stimuli-Responsive Polymers for Interface Engineering toward Enhanced Electrochemical Analysis of Neurochemicals. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 13171–13187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zou, R.; Liao, C.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, S.; Chang, G.; He, H. A Transistor Array Biosensor Based on Reduced Graphene Oxide Prepared Electrochemically for Detection of Multiplex Circulating miRNAs of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Human Serum. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 438, 137787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Dong, J.; Yu, T.; Pan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Accurate Diagnosis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by Detection of miRNA-196a Biomarker in Exosome Using Solution-Gated Graphene Transistor with Antifouling Design. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2404572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, Y.; Tao, J.; Liu, G.; Li, B.; Teng, Y.; Xu, J.; Feng, L.; You, Z. Miniaturized and Portable Device for Noninvasive, Ultrasensitive and Point-of-Care Diagnosis by Engineered Metal-Carbide-Based Field Effect Transistor. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, X.; Gao, D.; Ma, Z.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y. A Microfluidics Chemiluminescence Immunosensor Based on Orientation of Antibody for HIV-1 P24 Antigen Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 395, 134510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, W.-T.; Ali, M.Y.; Mitea, V.; Wang, M.-J.; Howlader, M.M.R. Polyaniline-Based Bovine Serum Albumin Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor for Ultra-Trace-Level Detection in Clinical and Food Safety Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Jiang, X.; Bai, S.; Lai, M.; Yu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhou, R.; Jia, Y.; Yan, H.; Liang, Z.; et al. Clinically Accurate Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease via Single-Molecule Bioelectronic Label-Free Profiling of Multiple Blood Extracellular Vesicle Biomarkers. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2505262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xia, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Geng, Z.; Tang, K.; Erdem, A.; Zhu, B. Ready-to-Use OECT Biosensor toward Rapid and Real-Time Protein Detection in Complex Biological Environments. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 3369–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Fan, G.-C.; Luo, X. Electrochemical Biosensor Utilizing Low-Susceptibility Macrocyclic Stapled Peptide to Mitigate Biofouling for Reliable Protein Detection in Human Serum. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 7343–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Shi, R.; Zhang, L.; Mak, W.C. Rational Molecular Design of Aniline-Based Donor–Acceptor Conducting Polymers Enhancing Ionic Molecular Interaction for High-Performance Wearable Bioelectronics. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2025, 14, 2501929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H.; Tang, C.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; et al. Co-Extrusion Strategy for Continuously Fabricating Flexible Fiber Electrochemical Sensors with High Stability and Consistency. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhou, L.; Liang, Q.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Jia, K.; Chu, H.; Luo, Y.; Qiu, L.; Peng, H.; et al. All-in-One Multifunctional and Stretchable Electrochemical Fiber Enables Health-Monitoring Textile with Trace Sweat. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakavath, K.; Kafley, C.; Sukumaran, R.A.; Umadevi, D.; Kotagiri, Y.G. Advanced Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Electrochemical Nanosensor for the Sensitive Detection of Atrazine in Agricultural Fields. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschoalin, R.T.; Gomes, N.O.; Almeida, G.F.; Bilatto, S.; Farinas, C.S.; Machado, S.A.S.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Oliveira, O.N.; Raymundo-Pereira, P.A. Wearable Sensors Made with Solution-Blow Spinning Poly(Lactic Acid) for Non-Enzymatic Pesticide Detection in Agriculture and Food Safety. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 199, 113875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Chen, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, L.; Huang, M.; Xu, B. Boosted Photoelectrochemical Sensor for Methyl Parathion Detection in Vegetables Based on COF@Bi2WO6 Quantum Dots Nanocomposites Grafted Electron Donor–Acceptor Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adane, W.D.; Chandravanshi, B.S.; Tessema, M. Hypersensitive Electrochemical Sensor Based on Thermally Annealed Gold–Silver Alloy Nanoporous Matrices for the Simultaneous Determination of Sulfathiazole and Sulfamethoxazole Residues in Food Samples. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 140071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhu, N.; Sha, J.; Fang, X.; Cao, H.; Ye, T.; Yuan, M.; Gu, H.; Xu, F. A Novel pH-Stable Chitosan/Aptamer Imprinted Polymers Modified Electrochemical Biosensor for Simultaneous Detection of Pb2+ and Hg2+. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 144, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Dong, F.; Rodas-Gonzalez, A.; Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Chen, S.; Zheng, H.-B.; Wang, S. Simultaneous Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Food Samples Using a Hypersensitive Electrochemical Sensor Based on APTES-Incubated MXene-NH2@CeFe-MOF-NH2. Food Chem. 2025, 475, 143362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, M.M.; Wouters, C.L.; Froehlich, C.E.; Nguyen, T.B.; Caldwell, R.; Riley, K.L.; Roy, P.; Reineke, T.M.; Haynes, C.L. A Machine Learning-Enabled SERS Sensor: Multiplex Detection of Lipopolysaccharides from Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 45139–45149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tan, F.; Huang, S.; Zu, J.; Guo, W.; Cui, B.; Fang, Y. Ultrasensitive Staphylococcus aureus Detection via Machine Learning-Optimized Bacterial-Imprinted Photoelectrochemical Biosensor with Active/Passive Dual-Mode Validation. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 16456–16464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, P.; Hao, W.; Han, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Liang, P. Additional Polypyrrole as Conductive Medium in Artificial Electrochemically Active Biofilm to Increase Sensitivity for Water Quality Early Warning. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 190, 113453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhen, G. Spatial Distribution and Nitrogen Metabolism Behaviors of Anammox Biofilms in Bioelectrochemical System Regulated by Continuous/Intermittent Weak Electrical Stimulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwaran, M.; Kumar, K.K.S. A Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Multiple Heavy Metal Ions in Water Using PAni–RYFG/GCE Modified Electrode: Experimental and DFT Studies. Microchem. J. 2025, 213, 113654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharkova, A.S.; Medvedeva, A.S.; Kuznetsova, L.S.; Gertsen, M.M.; Kolesov, V.V.; Arlyapov, V.A.; Reshetilov, A.N. A “2-in-1” Bioanalytical System Based on Nanocomposite Conductive Polymers for Early Detection of Surface Water Pollution. Polymers 2024, 16, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.; Thadathil, D.A.; Ghosh, M.; Varghese, A. Enzyme Immobilized Conducting Polymer-Based Biosensor for Electrochemical Determination of the Eco-Toxic Pollutant p-Nonylphenol. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 460, 142591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyakin, A.S.; Volkov, A.N. An Electrochemical Sensor for Determination of Methane and Carbon Dioxide in Biogas. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 169, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Farani, M.; Kim, H.; Alhammadi, M.; Huh, Y.S. The Detection of Toxic Gases (CO, FN3, HI, N2, CH4, N2O, and O3) Using a Wearable Kapton–Graphene Biosensor for Environmental and Biomedical Applications. Carbon Lett. 2025, 35, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Key Mechanism | Sensitivity | Stability | Cost | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIPs | Specific binding cavities enrich target molecules | High | High (Thermal/Chemical) | Low | Slow binding kinetics; Template leakage |

| Nanocomposites | Synergistic effect of conductivity and catalysis | Very High | Moderate | Moderate/High | Aggregation of nanofillers; Complex synthesis |

| Hydrogels | 3D porous structure increases loading capacity | High | Moderate | Low | Trade-off between conductivity and mechanics |

| Biointerfaces | Mimics natural environment to reduce impedance | Moderate | Low (In vivo) | High | Long-term biological stability; Fabrication complexity |

| Stimuli-Responsive | Dynamic modulation of signal via phase change | High | Moderate | Moderate | Response hysteresis; Environmental cross-sensitivity |

| Target Analyte | System Type/Material Structure | Amplification Mechanism | Key Performance Indicators | Application Scenario/Advantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA-196a | rGO transistor array with PAA/PEDOT composite layer and Y-shaped DNA probe | Conductive polymer forms continuous charge transport channels; 3D DNA structure enhances electrostatic perturbation response | LOD ~ 10−19 M; AUC = 0.98 | Clinical plasma samples; highly sensitive detection without nucleic acid preamplification | [82] |

| miRNA-122 | MC@CNT heterojunction miniaturized FET | High surface area and rapid electron transfer pathways; 42% enhancement in transconductance | Fast response; noninvasive urine detection | Home-use and POCT (point-of-care testing) applications | [83] |

| Alzheimer’s disease-related proteins | Microelectrode array-integrated OECT (organic electrochemical transistor) | Electrochemical multi-point signal amplification; simultaneous multi-target detection | Zeptomolar-level sensitivity; 100% classification accuracy | Multiplexed, label-free detection | [86] |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | OECT modified with zwitterionic conductive polymer PEDOT-PC | Intrinsic antifouling and charge-regulated interface | LOD 0.11 pg/mL; response time 60 s | Ready-to-use POCT; anti-biofouling capability | [87] |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | Stapled-peptide-modified electrochemical sensing interface | Enhanced protease resistance; improved long-term signal stability | Results consistent with clinical standards | Robust protein detection; long-term storage stability | [88] |

| pH (sweat) | Molecularly engineered polyaniline | H+ doping/de-doping-driven electrochemical signal amplification | Sensitivity 65.193 mV/pH; stability improved 3.6–9.0× | Long-term sweat monitoring; flexible wearable sensors | [89] |

| H2O2/Ascorbic acid | Active nanocomponents embedded in 3D PEDOT:PSS network | Structure-function integrated conductive fiber; stable signal amplification | <10% performance decay after 14 days or 1000 bending cycles | Continuous health monitoring; wearable integration | [90] |

| Category | Target Analyte | Material System | Analytical Performance | Key Innovation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pesticide residues | Atrazine | MIP/rGO/PPy electrochemical composite sensor | Rapid detection with excellent linearity and reproducibility | Biomimetic recognition by MIP combined with highly conductive hybrid structure for enhanced electron transport | [92] |

| Broad-spectrum organophosphate pesticides | Flexible PLA substrate with screen-printed electrodes | Wearable, in situ, and nondestructive detection | Direct attachment to fruit and vegetable surfaces enabling on-site monitoring | [93] | |

| Methyl parathion | MIP-Bi2WO6 QDs/COF photoelectrochemical sensor | Detection limit down to femtomolar level | Heterojunction-assisted photogenerated electron amplification significantly enhances sensitivity | [94] | |

| Antibiotic residues | Sulfathiazole (SFT), Sulfamethoxazole (SFM) | TA-Au-Ag-ANpM/f-MWCNTs/poly(L-serine) composite electrode | Detection limit at picomolar level; recovery 95–102% | Au-Ag alloy and CNT synergy enhances electrocatalytic activity | [95] |

| Heavy metal ions | Pb2+, Hg2+ | Chitosan/aptamer molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) | Highly selective detection; stable signal in pH 6–8 | Aptamer conformational stabilization + MIP-assisted molecular recognition improves anti-interference performance | [96] |

| Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+ | MXene@CeFe-MOF-NH2 electrochemical sensor | Nanomolar detection limits; excellent signal stability | Enrichment-driven high surface area composite enables simultaneous multi-metal ion detection | [97] | |

| Foodborne pathogens | Salmonella, E. coli O26:B6, O111:B4 lipopolysaccharides | pHEMA-based SERS sensor with machine learning | Detection limit 0.7 μg/mL; 100% classification accuracy | Non-specific polymeric capture coupled with spectral pattern recognition via machine learning | [98] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Dual-mode BIPs-PEC photoelectrochemical biosensor with machine learning | Detection limit 1.06 CFU/mL; excellent anti-interference performance | Active/passive dual-mode sensing with intelligent signal interpretation | [99] |

| Target Analyte | Material System | Detection Principle/Mechanism | Performance Features and Analytes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive water quality (pollution warning) | Polypyrrole (PPy)-enhanced artificial electroactive biofilm (Shewanella oneidensis) | PPy improves conductivity and electron transfer efficiency, regulating electron-proton coupling in biofilms | Significantly enhanced sensitivity, enabling rapid water quality warning | [100] |

| Nitrogen pollution in water | Electrically stimulated anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) biofilm | Weak electric field regulates biofilm structure and electron transfer pathways | Enhanced nitrogen removal rate and system stability | [101] |

| Heavy metals (Hg2+, Pb2+) | Polyaniline-Reactive Yellow 42 dye composite-modified electrode | Electron transfer enhancement verified by DFT calculations | Simultaneous detection of Hg2+ (LOD 2 nM) and Pb2+ (LOD 6.2 nM); applicable to complex water samples | [102] |

| Multi-parameter water analysis (BOD, toxicity) | Nanocomposite conducting polymer-microbial consortium system | Synergistic amplification of biocatalytic reactions and nanoscale conductive pathways | Simultaneous detection of BOD and toxicity with high sensitivity and rapid response | [103] |

| Organic pollutants (p-nonylphenol, PNP) | Laccase-immobilized conducting polymer electrode | Enzymatic oxidation-electron transfer coupling mechanism | Nanomolar detection limit; ≈100% recovery in real water samples; suitable for endocrine disruptor monitoring | [104] |

| Gaseous pollutants (CH4, CO2) | Dual-cell solid electrolyte electrochemical sensor | Gas-electrolyte interfacial reactions induce potential difference | Simultaneous CH4 and CO2 detection; response < 1.5 min; suitable for high-temperature industrial environments | [105] |

| Multiple gaseous pollutants (CO, N2O, O3, CH4) | Graphene-polyimide (Kapton) flexible gas sensor | Gas adsorption induces resonance frequency shift in graphene | High sensitivity, low power consumption (1.5 mW), and excellent flexibility for noninvasive environmental monitoring | [106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Gao, D. Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification Mechanisms for Bioelectronic Detection: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Biosensors 2025, 15, 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120808

Sun Y, Gao D. Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification Mechanisms for Bioelectronic Detection: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):808. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120808

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Ying, and Dan Gao. 2025. "Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification Mechanisms for Bioelectronic Detection: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120808

APA StyleSun, Y., & Gao, D. (2025). Polymer-Mediated Signal Amplification Mechanisms for Bioelectronic Detection: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Biosensors, 15(12), 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120808