Features of Chaperone Induction by 9-Aminoacridine and Acridine Orange

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Cultivation Conditions

2.2. Chemical Compounds

2.3. Luminescent Response Measurements

2.4. Luminescence Shielding Test

2.5. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

2.6. Melting Point of the Proteins

3. Results

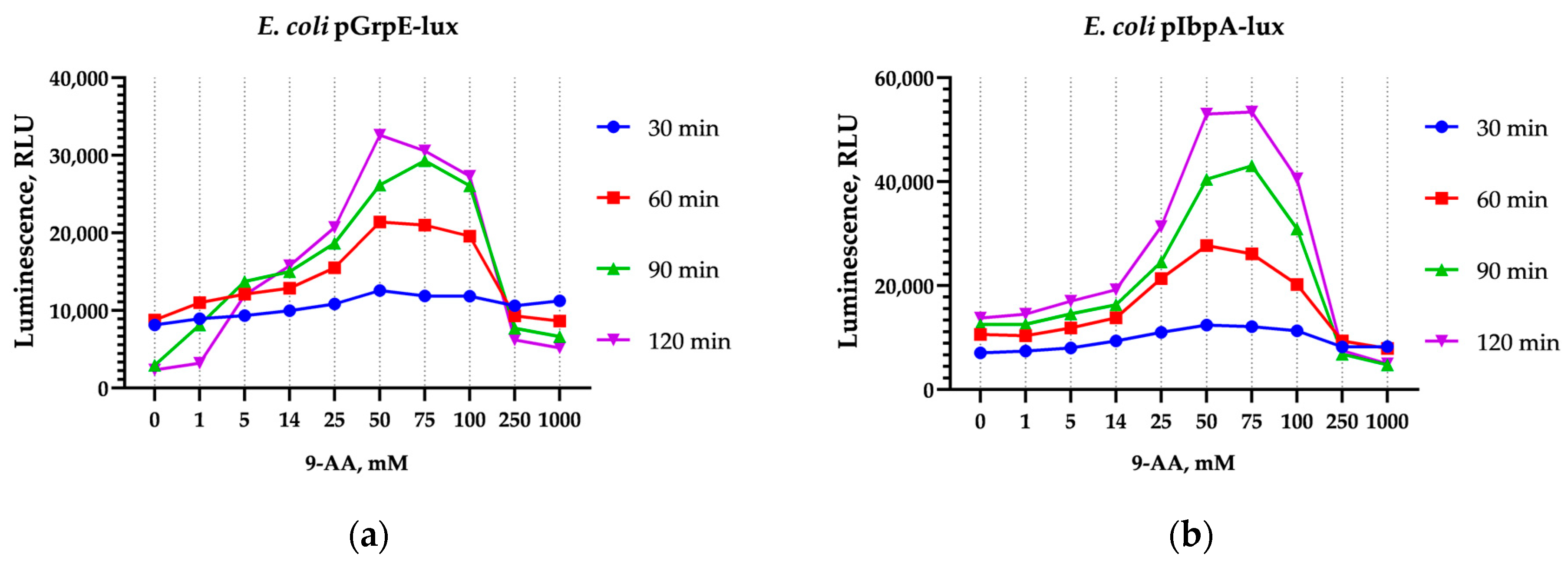

3.1. Activation of Luminescence by 9-AA and AO

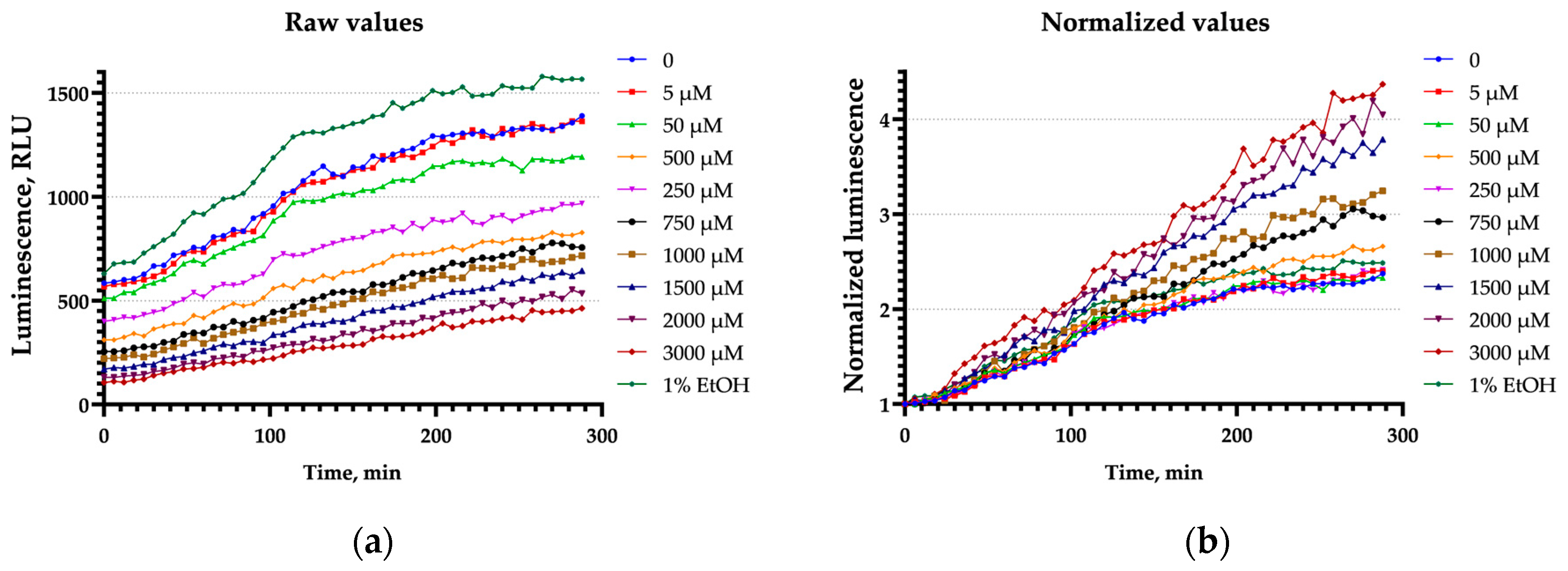

3.2. Toxicity of AO and 9-AA to E. coli

3.3. Bioluminescence Shielding

3.4. Denaturing Properties of 9-AA and AO

3.5. mRNA Level of grpE and ibpA Genes

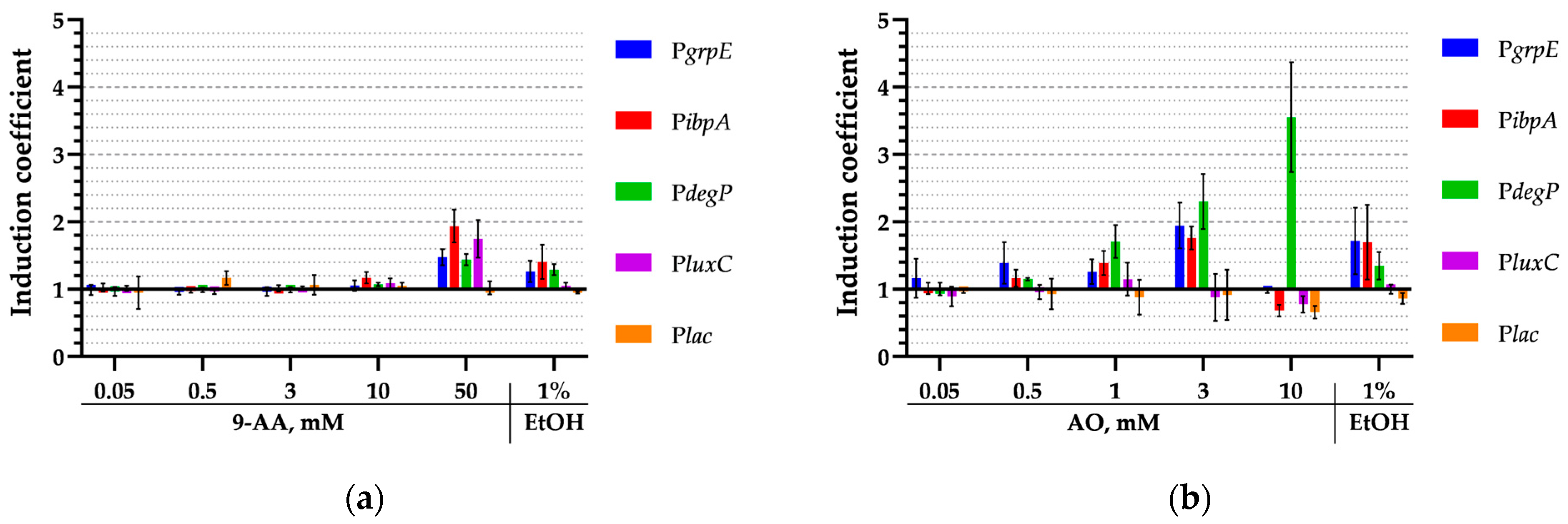

3.6. Activation of Various Heat Shock Promoters

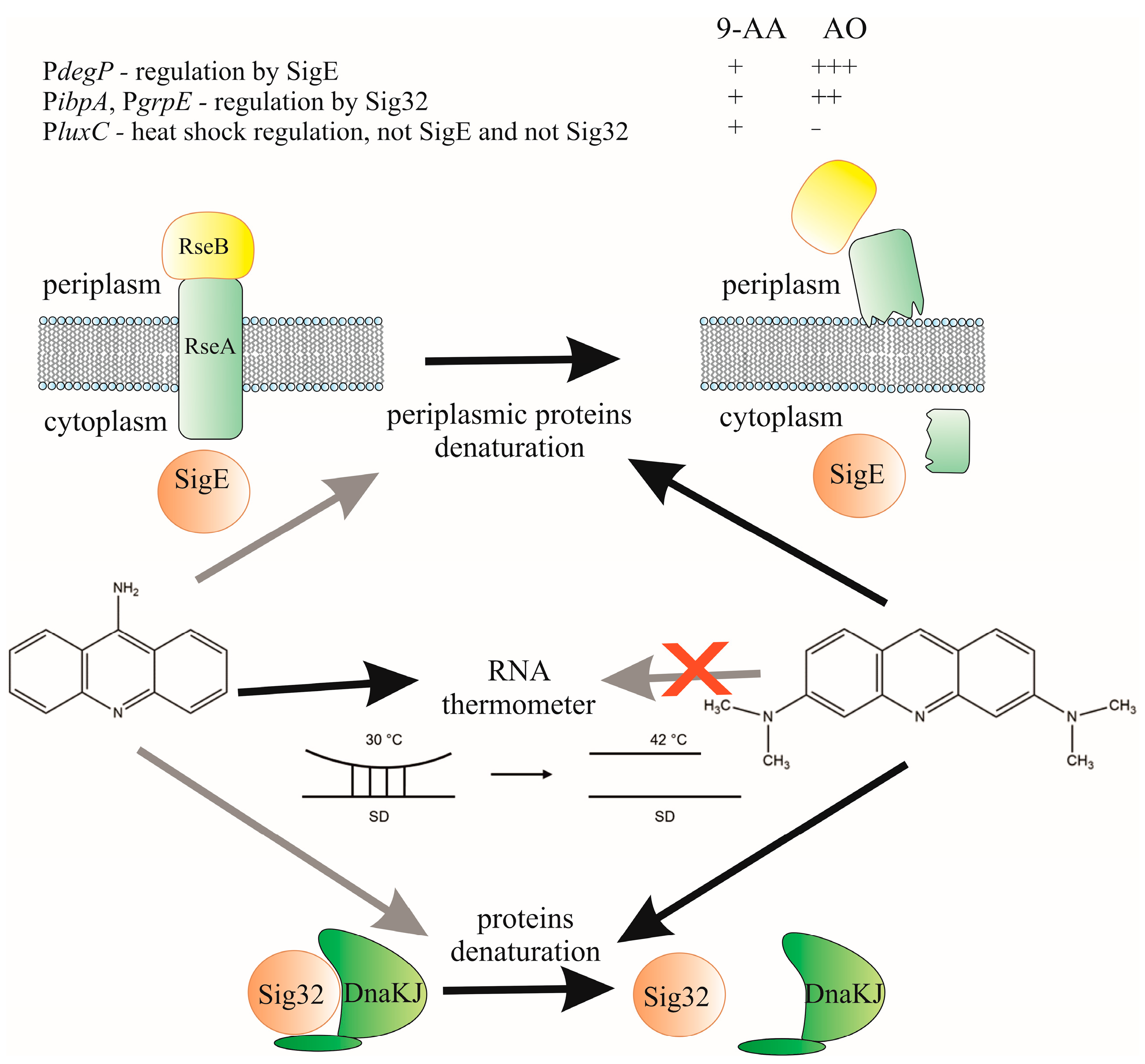

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Auparakkitanon, S.; Noonpakdee, W.; Ralph, R.K.; Denny, W.A.; Wilairat, P. Antimalarial 9-Anilinoacridine Compounds Directed at Hematin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3708–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.M.; Mali, M.D.; Patel, S.K. Bernthsen Synthesis, Antimicrobial Activities and Cytotoxicity of Acridine Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6324–6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artusi, S.; Nadai, M.; Perrone, R.; Biasolo, M.A.; Palù, G.; Flamand, L.; Calistri, A.; Richter, S.N. The Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Genome Contains Multiple Clusters of Repeated G-Quadruplex: Implications for the Antiviral Activity of a G-Quadruplex Ligand. Antivir. Res. 2015, 118, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasleem, H.U.B.N.F. Acridine Derivatives and Their Pharmacology. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Res. 2018, 11, 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Panchal, N.B.; Patel, P.H.; Chhipa, N.M.; Parmar, R.S. Acridine a Versatile Heterocyclic Moiety As Anticancer Agent. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2020, 11, 4739. [Google Scholar]

- Varakumar, P.; Rajagopal, K.; Aparna, B.; Raman, K.; Byran, G.; Gonçalves Lima, C.M.; Rashid, S.; Nafady, M.H.; Emran, T.B.; Wybraniec, S. Acridine as an Anti-Tumour Agent: A Critical Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- René, B.; Auclair, C.; Fuchs, R.P.P.; Paoletti, C. Frameshift Mutagenesis in Escherichia Coli by Reversible DNA Intercalators: Sequence Specificity. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1988, 202, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozurkova, M.; Sabolova, D.; Kristian, P. A New Look at 9-Substituted Acridines with Various Biological Activities. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2021, 41, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupar, J.; Rupar, J.; Brborić, J.; Grahovac, J.; Radulović, S.; Skok, Ž.; Ilaš, J.; Aleksić, M. Synthesis and Evaluation of Anticancer Activity of New 9-Acridinyl Amino Acid Derivatives. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.M.; Jacobson, B.A.; Jay-Dixon, J.; Patel, M.R.; Kratzke, R.A.; Raza, A. Targeting Topoisomerase II Activity in NSCLC with 9-Aminoacridine Derivatives. Anticancer. Res. 2015, 35, 5211–5218. [Google Scholar]

- Mangueira, V.M.; de Sousa, T.K.G.; Batista, T.M.; de Abrantes, R.A.; Moura, A.P.G.; Ferreira, R.C.; de Almeida, R.N.; Braga, R.M.; Leite, F.C.; Medeiros, K.C.d.P.; et al. A 9-Aminoacridine Derivative Induces Growth Inhibition of Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma Cells and Antinociceptive Effect in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 963736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikin, L.; Pestov, D.G. 9-Aminoacridine Inhibits Ribosome Biogenesis by Targeting Both Transcription and Processing of Ribosomal RNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byvaltsev, V.A.; Bardonova, L.A.; Onaka, N.R.; Polkin, R.A.; Ochkal, S.V.; Shepelev, V.V.; Aliyev, M.A.; Potapov, A.A. Acridine Orange: A Review of Novel Applications for Surgical Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 466022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, T.; Kusuzaki, K.; Matsumine, A.; Murata, H.; Marunaka, Y.; Hosogi, S.; Uchida, A.; Sudo, A. Photodynamic Therapy with Acridine Orange in Musculoskeletal Sarcomas. J. Bone Jt. Surg.-Ser. B 2010, 92, 460–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pompo, G.; Kusuzaki, K.; Ponzetti, M.; Leone, V.F.; Baldini, N.; Avnet, S. Radiodynamic Therapy with Acridine Orange Is an Effective Treatment for Bone Metastases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lin, J.F.; Tsai, T.F.; Chen, H.E.; Chou, K.Y.; Yang, S.C.; Tang, Y.M.; Hwang, T.I.S. Acridine Orange Exhibits Photodamage in Human Bladder Cancer Cells under Blue Light Exposure. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, J.; Roy, G.; Lambert, H.; Chretien, P.; Landry, J. Increased Survival after Treatments with Anticancer Agents of Chinese Hamster Cells Expressing the Human Mr 27,000 Heat Shock Protein. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 5245–5252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dubrez, L.; Causse, S.; Borges Bonan, N.; Dumétier, B.; Garrido, C. Heat-Shock Proteins: Chaperoning DNA Repair. Oncogene 2020, 39, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Chi, Y. Advances in the Study of HSP70 Inhibitors to Enhance the Sensitivity of Tumor Cells to Radiotherapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 942828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbenko, V.N.; Kuznetsova, L.V.; Kalinin, V.L. Mutantnye Alleli Radiorezisteentnosti Iz Shtamma Escherichia Coli Gam(r)444: Klonirovanie i Predvaritel’naia Kharakteristika. Genetika 1994, 30, 756–762. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, J.H.; Walker, G.C. GroEL and DnaK Genes of Escherichia Coli Are Induced by UV Irradiation and Nalidixic Acid in an HtpR+-Dependent Fashion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 20, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamer, J.; Bujard, H.; Bukau, B. Physical Interaction between Heat Shock Proteins DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE and the Bacterial Heat Shock Transcription Factor Σ32. Cell 1992, 69, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowska, E.; Wawrzynów, A.; Taylor, A. IbpA and IbpB, the New Heat-Shock Proteins, Bind to Endogenous Escherichia Coli Proteins Aggregated Intracellularly by Heat Shock. Biochimie 1996, 78, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, P.N.; Snyder, W.B.; Cosma, C.L.; Davis, L.J.B.; Silhavy, T.J. The Cpx Two-Component Signal Transduction Pathway of Escherichia Coli Regulates Transcription of the Gene Specifying the Stress-Inducible Periplasmic Protease, DegP. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, V.V.; Bazhenov, S.V.; Kononchuk, O.V.; Matveeva, V.O.; Zarubina, A.P.; Spiridonov, S.E.; Manukhov, I.V. Photorhabdus Lux-Operon Heat Shock-like Regulation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ebrahim, R.N.; Alekseeva, M.G.; Bazhenov, S.V.; Fomin, V.V.; Mavletova, D.A.; Nesterov, A.A.; Poluektova, E.U.; Danilenko, V.N.; Manukhov, I.V. ClpL Chaperone as a Possible Component of the Disaggregase Activity of Limosilactobacillus Fermentum U-21. Biology 2024, 13, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, V.Y.; Manukhov, I.V.; Zavilgelskii, G.B. Lux-Biosensors for Detection of SOS-Response, Heat Shock, and Oxidative Stress. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2010, 46, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, V.Y.; Ryzhenkova, K.V.; Manukhov, I.V.; Zavilgelsky, G.B. Inducible Specific Lux-Biosensors for the Detection of Antibiotics: Construction and Main Parameters. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2014, 50, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukhov, I.V.; Kotova, V.Y.; Mal’dov, D.G.; Il’ichev, A.V.; Bel’kov, A.P.; Zavil’gel’skii, G.B. Induction of Oxidative Stress and SOS Response in Escherichia Coli by Vegetable Extracts: The Role of Hydroperoxides and the Synergistic Effect of Simultaneous Treatment with Cisplatinum. Microbiology 2008, 77, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukhov, I.V.; Rastorguev, S.M.; Eroshnikov, G.E.; Zarubina, A.P.; Zavil’gel’skii, G.B. Cloning and Expression of the Lux Operon of Photorhabdus Luminescens, Strain Zm1: The Nucleotide Sequence of LuxAB Genes and Basic Characteristics of Luciferase. Russ. J. Genet. 2000, 36, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyk, T.K.; Rosson, R.A. Photorhabdus Luminescens LuxCDABE Promoter Probe Vectors. Methods Mol. Biol. 1998, 102, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavilgelsky, G.B.; Kotova, V.Y.; Manukhov, I.V. Action of 1,1-Dimethylhydrazine on Bacterial Cells Is Determined by Hydrogen Peroxide. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2007, 634, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksharov, M.I.; Ugarova, N.N. Random Mutagenesis of Luciola Mingrelica Firefly Luciferase. Mutant Enzymes with Bioluminescence Spectra Showing Low PH Sensitivity. Biochemistry 2008, 73, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarev, N.A.; Bagaeva, D.F.; Bazhenov, S.V.; Buben, M.M.; Bulushova, N.V.; Ryzhykau, Y.L.; Okhrimenko, I.S.; Zagryadskaya, Y.A.; Maslov, I.V.; Anisimova, N.Y.; et al. Methionine Gamma Lyase Fused with S3 Domain VGF Forms Octamers and Adheres to Tumor Cells via Binding to EGFR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 691, 149319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaneva, I.R.; Weiss, B. SoxR, a Locus Governing a Superoxide Response Regulon in Escherichia Coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4197–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imray, P.; MacPhee, D.G. Induction of Frameshifts and Base-Pair Substitutions by Acridine Orange plus Visible Light in Bacteria. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1973, 20, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhedzhelava, D.A.; Egorov, I.A.; Tarasov, V.A. Induction of SOS Function in Escherichia Coli after Exposure to Various Types of Chemical Mutagens. Genetika 1989, 25, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kumar, G.S. Binding of Fluorescent Acridine Dyes Acridine Orange and 9-Aminoacridine to Hemoglobin: Elucidation of Their Molecular Recognition by Spectroscopy, Calorimetry and Molecular Modeling Techniques. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 159, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, W. Regulation of Bacterial Heat Shock Stimulons. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Absorption [Acridine Orange] | AAT Bioquest. Available online: https://www.aatbio.com/absorbance-uv-visible-spectrum-graph-viewer/acridine_orange (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Colepicolo, P.; Cho, K.W.; Poinar, G.O.; Hastings, J.W. Growth and Luminescence of the Bacterium Xenorhabdus Luminescens from a Human Wound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989, 55, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koksharov, M.I.; Ugarova, N.N. Triple Substitution G216N/A217L/S398M Leads to the Active and Thermostable Luciola Mingrelica Firefly Luciferase. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2011, 10, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pXen7 | pUC18 plasmid containing a cloned lux-operon from P. luminescens ZM1, controlled by its own promoter, Apr | [30] |

| pGrpE-lux | pDEW201 [31] vector containing a cloned PgrpE promoter from E. coli, transcriptionally fused with the luxCDABE genes from P. luminescens. Apr | [32] |

| pSoxS-lux | The same as pGrpE-lux but the PsoxS promoter is inserted | |

| pRpoE-lux | The same as pGrpE-lux but the PdegP promoter is inserted | |

| pIbpA-lux | The same as pGrpE-lux but the PibpA promoter is inserted | [27] |

| pDlac | The same as pGrpE-lux but the Plac promoter is inserted | [25] |

| pLR3 | pLR derivative containing the luc gene from L. mingrelica, controlled by PluxI promoter from A. fischeri, Apr | [33] |

| Substance, mM | Exposure Time, min | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | |

| H2O | 6874 ± 192 | 5985 ± 95 | 4958 ± 103 | 6028 + 87 |

| PQ, 0.4 | 6028 ± 87 | 15,219 ± 986 | 19,300 ± 1405 | 30,716 ± 2170 |

| AO, 5 | 79 ± 10 | 37± 8 | 29 ± 7 | 59 ± 11 |

| AO, 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PQ + AO, 5 | 85 ± 1 | 135 ± 20 | 220 ± 35 | 436 ± 76 |

| PQ + AO, 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Substance, mM | CFU, 107 | Luminescence, RLU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per well, 102 | Per well/CFU, 106 | ||

| H2O | 10 ± 5 | 79 | 64 |

| 9-AA, 5 | 7 ± 2 | 90 | 131 |

| 9-AA, 50 | 5 ± 3 | 159 | 233 |

| AO, 5 | 9 ± 5 | 8 | 12 |

| AO, 50 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fomin, V.V.; Smirnova, S.V.; Bazhenov, S.V.; Kurkieva, A.G.; Bondarev, N.A.; Egorenkova, D.M.; Sakharov, D.I.; Manukhov, I.V.; Abilev, S.K. Features of Chaperone Induction by 9-Aminoacridine and Acridine Orange. Biosensors 2025, 15, 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120800

Fomin VV, Smirnova SV, Bazhenov SV, Kurkieva AG, Bondarev NA, Egorenkova DM, Sakharov DI, Manukhov IV, Abilev SK. Features of Chaperone Induction by 9-Aminoacridine and Acridine Orange. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120800

Chicago/Turabian StyleFomin, Vadim V., Svetlana V. Smirnova, Sergey V. Bazhenov, Aminat G. Kurkieva, Nikolay A. Bondarev, Daria M. Egorenkova, Daniil I. Sakharov, Ilya V. Manukhov, and Serikbai K. Abilev. 2025. "Features of Chaperone Induction by 9-Aminoacridine and Acridine Orange" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120800

APA StyleFomin, V. V., Smirnova, S. V., Bazhenov, S. V., Kurkieva, A. G., Bondarev, N. A., Egorenkova, D. M., Sakharov, D. I., Manukhov, I. V., & Abilev, S. K. (2025). Features of Chaperone Induction by 9-Aminoacridine and Acridine Orange. Biosensors, 15(12), 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120800