Digging into the Solubility Factor in Cancer Diagnosis: A Case of Soluble CD44 Protein

Abstract

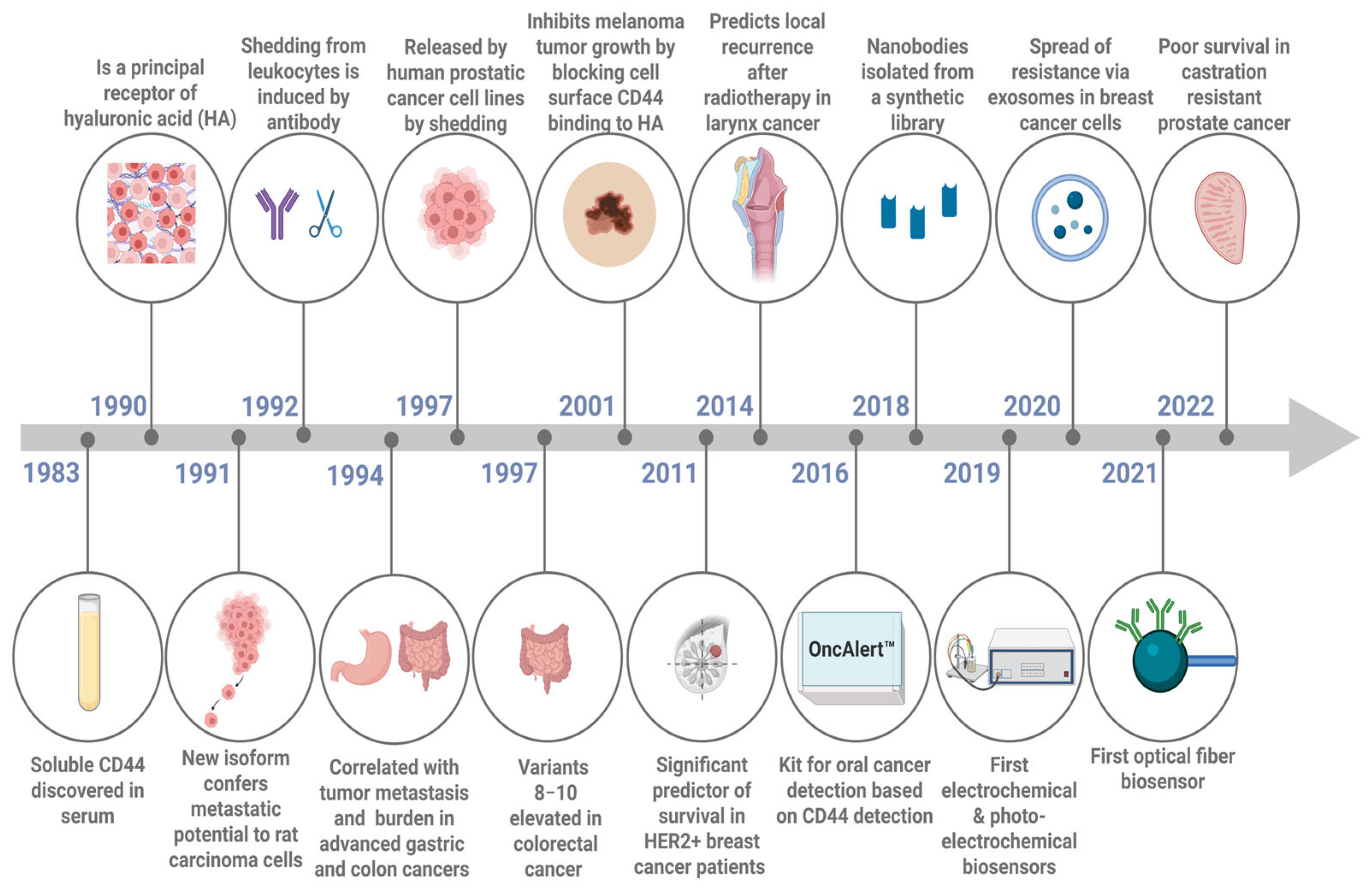

1. Introduction

2. Shedding of the Soluble Form of CD44 from the Cell

3. The Role of Soluble CD44 Protein as a Cancer Biomarker

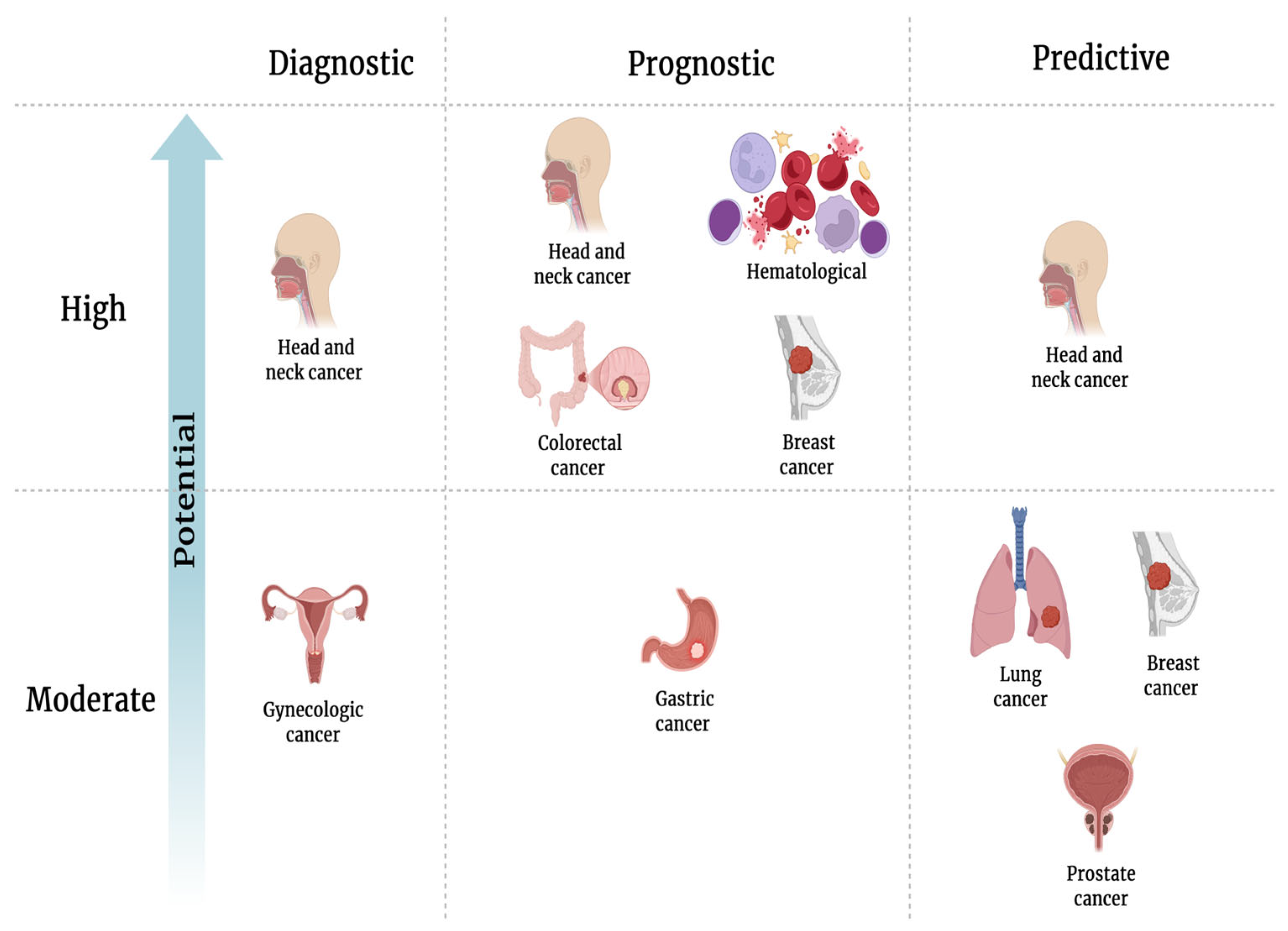

3.1. SolCD44 as a Diagnostic Biomarker for Early Cancer Detection and Classification of Cancer into Subgroups

3.2. SolCD44 as a Prognostic Biomarker

3.3. SolCD44 as a Predictive Biomarker

3.4. SolCD44 as a Co-Player with Other Biomarkers

3.5. Comparison of CD44 Expression in Tissue and Biological Fluid

3.6. CD44 as a Component of Serum Exosomes

3.7. SolCD44 in Different Biological Fluids

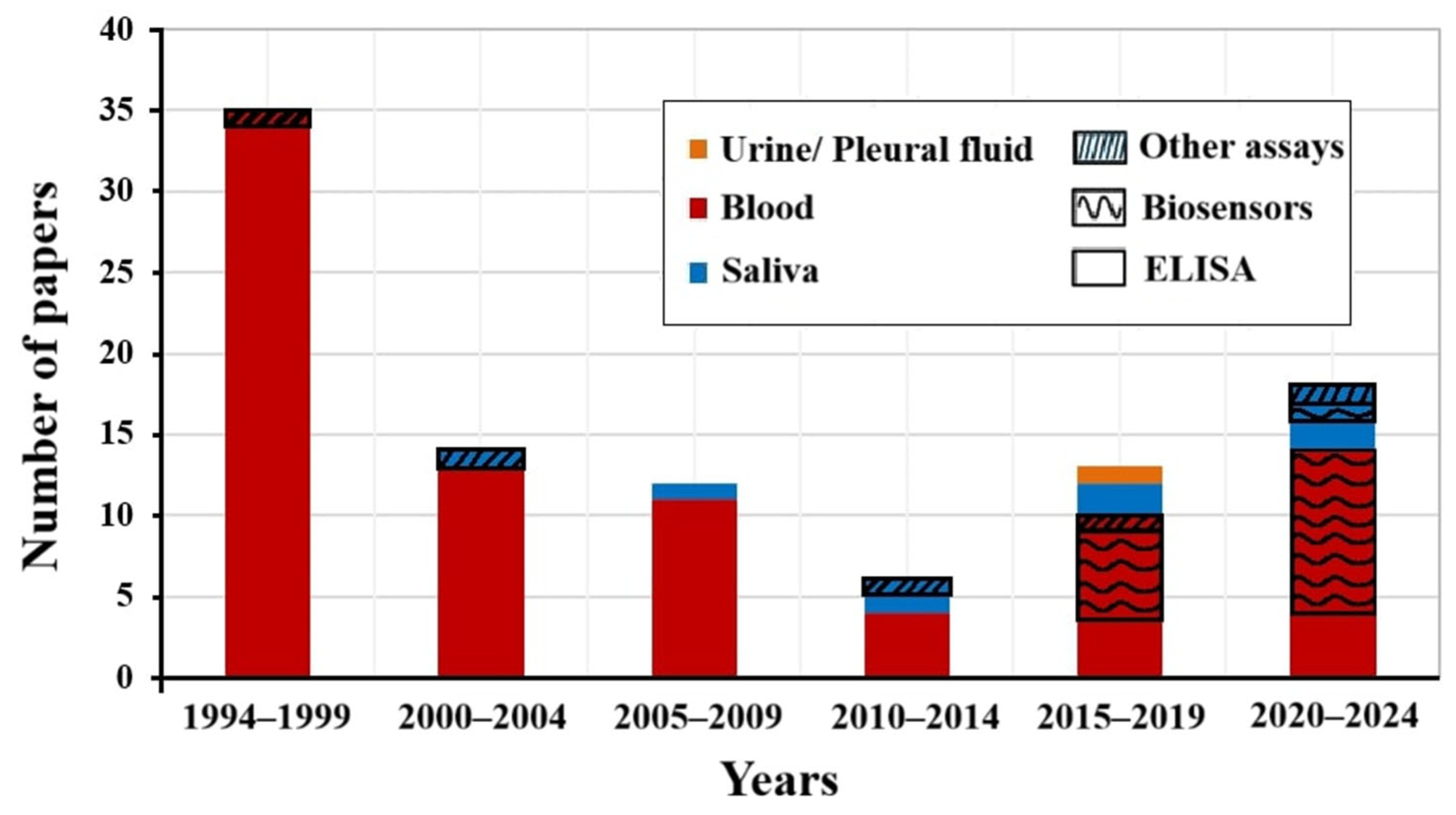

4. Assays for CD44 Protein Detection

4.1. Ligands Against solCD44

4.1.1. Hyaluronic Acid

4.1.2. Antibodies

4.1.3. Aptamers

4.1.4. Emerging Ligands Against solCD44

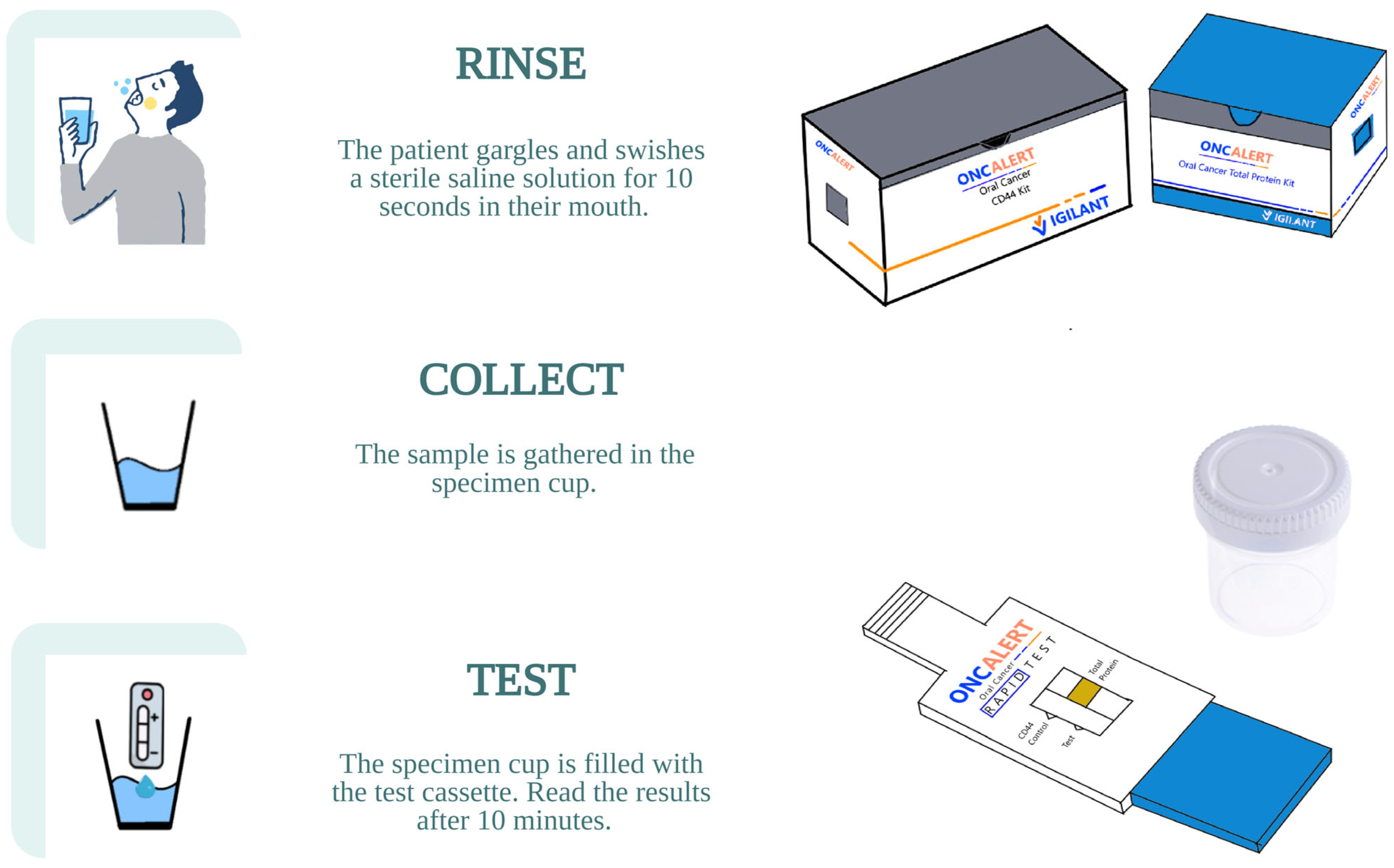

4.2. Commercially Available Assays

4.3. Biosensors and Other Assays

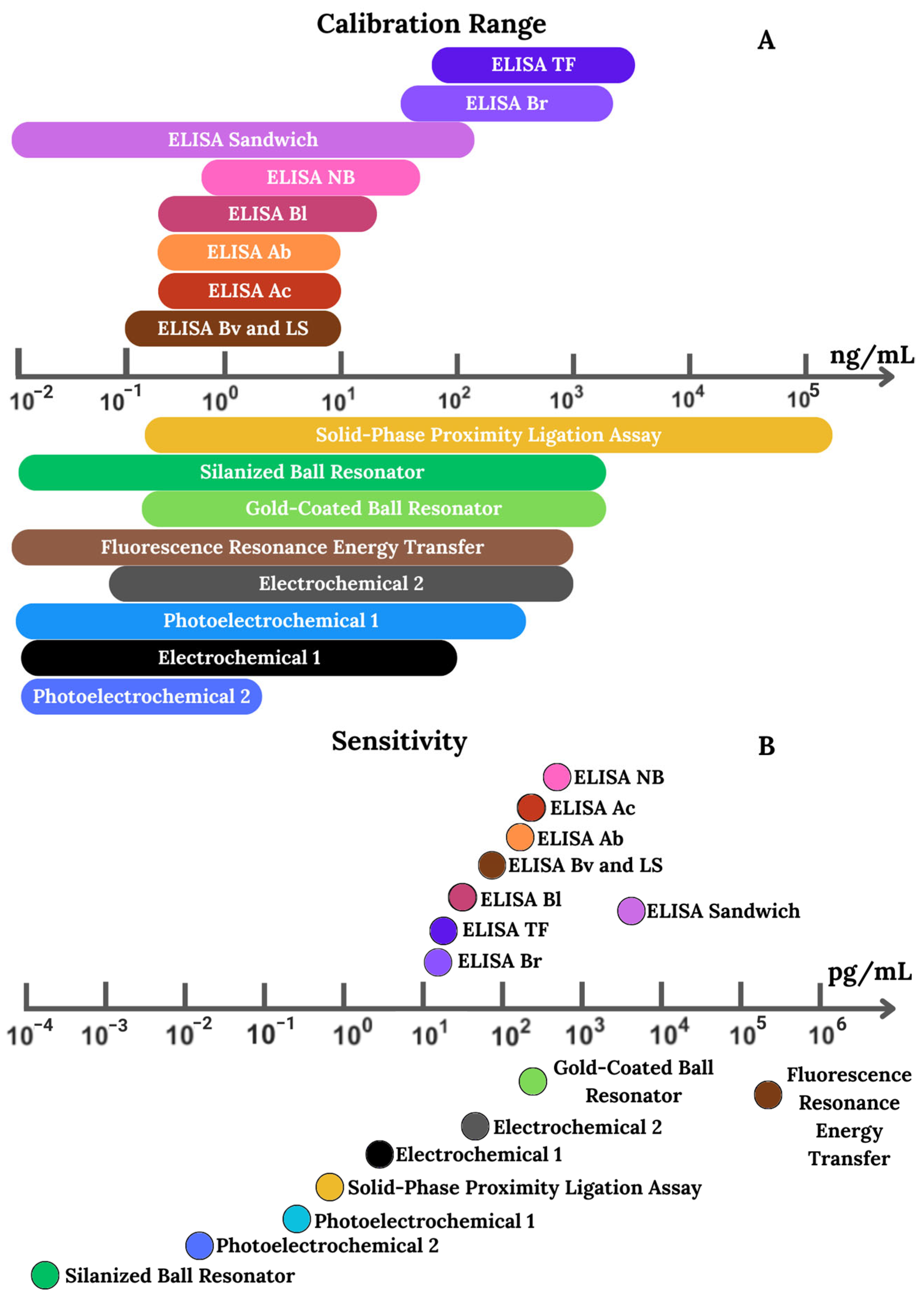

4.4. Performance of the Assays

5. CD44 Biomarker: Cell vs. Soluble Protein

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| solCD44 | Soluble CD44 protein in serum (circulatory), saliva, urine, or other biological fluids (general idea) or total soluble CD44 (standard and isoforms) |

| solCD44std | Standard form of soluble CD44 (wild type) without variable exons (exons 1–5, 16–20) |

| solCD44v1-v10 | Soluble variants (isoforms) of CD44 (v1–v10) |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Main extracellular ligand that binds CD44 for adhesion and signaling; also used as a ligand in biosensors |

| CD44 shedding | Proteolytic cleavage releasing soluble CD44, driven by ADAM10/17 and MMP14 |

References

- Dasari, S.; Rajendra, W.; Valluru, L. Evaluation of soluble CD44 protein marker to distinguish the premalignant and malignant carcinoma cases in cervical cancer patients. Med. Oncol. 2014, 31, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, A.D.; Palecek, S.P. Protein Analytical Assays for Diagnosing, Monitoring, and Choosing Treatment for Cancer Patients. J. Healthc. Eng. 2012, 3, 503–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landegren, U.; Hammond, M. Cancer diagnostics based on plasma protein biomarkers: Hard times but great expectations. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lone, S.N.; Nisar, S.; Masoodi, T.; Singh, M.; Rizwan, A.; Hashem, S.; El-Rifai, W.; Bedognetti, D.; Batra, S.K.; Haris, M.; et al. Liquid biopsy: A step closer to transform diagnosis, prognosis and future of cancer treatments. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodison, S.; Tarin, D. Current status of CD44 variant isoforms as cancer diagnostic markers. Histopathology 1998, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesrati, M.H.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mohtar, M.A.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbanjo, L.T.; Chellaiah, M.A. CD44: A Multifunctional Cell Surface Adhesion Receptor Is a Regulator of Progression and Metastasis of Cancer Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.M.; Zuo, X.S.; Wei, D.Y. Concise Review: Emerging Role of CD44 in Cancer Stem Cells: A Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Target. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.X.; Niu, M.K.; Yuan, X.; Wu, K.M.; Liu, A.G. CD44 as a tumor biomarker and therapeutic target. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basakran, N.S. CD44 as a potential diagnostic tumor marker. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.J.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J.W. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: Therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.C.; Alpay, S.N.; Klostergaard, J. CD44: A validated target for improved delivery of cancer therapeutics. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Yang, C.X.; Gao, F. The state of CD44 activation in cancer progression and therapeutic targeting. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 7970–7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghobi, Z.; Movassaghpour, A.; Talebi, M.; Shadbad, M.A.; Hajiasgharzadeh, K.; Pourvahdani, S.; Baradaran, B. The role of CD44 in cancer chemoresistance: A concise review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 903, 174147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothy, S. CD44 and its partners in metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2003, 20, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Mahtab, A.; Rai, N.; Rawat, P.; Ahmad, F.J.; Talegaonkar, S. Emerging Role of CD44 Receptor as a Potential Target in Disease Diagnosis: A Patent Review. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2017, 11, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emich, H.; Chapireau, D.; Hutchison, I.; Mackenzie, I. The potential of CD44 as a diagnostic and prognostic tool in oral cancer. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 44, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, K.L.; Choy, W.; Sidhu, S.; Pelargos, P.; Bui, T.T.; Voth, B.; Barnette, N.; Yang, I. The role of CD44 in glioblastoma multiforme. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 34, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponta, H.; Sherman, L.; Herrlich, P.A. CD44: From adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, J.; Oliveira, R. CD44 and Its Role in Solid Cancers—A Review: From Tumor Progression to Prognosis and Targeted Therapy. Front. Biosci. 2025, 30, 24821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Orian-Rousseau, V. CD44: A stemness driver, regulator, and marker-all in one? Stem Cells 2024, 42, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandalis, S. CD44 Intracellular Domain: A Long Tale of a Short Tail. Cancers 2023, 15, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telen, M.J.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Haynes, B.F. Human erythrocyte antigens. Regulation of expression of a novel erythrocyte surface antigen by the inhibitor Lutheran In(Lu) gene. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 71, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lim, J.M.; Lee, J.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, K.P.; Surh, Y.J. Breast Cancer Cell-Derived Soluble CD44 Promotes Tumor Progression by Triggering Macrophage IL1 beta Production. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenkovic, I.; Yu, Q. Shedding Light on Proteolytic Cleavage of CD44: The Responsible Sheddase and Functional Significance of Shedding. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1321–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Jin, D.; WU, M.; Mo, J.; Sy, M. Potential use of soluble CD44 in serum as indicator of tumor burden and metastasis in patients with gastric or colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ristamaki, R.; Joensuu, H.; Jalkanen, S. Does soluble CD44 reflect the clinical behavior of human cancer? In Attempts to Understand Metastasis Formation Iii: Therapeutic Approaches for Metastasis Treatment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 213, pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cichy, J.; Pure, E. The liberation of CD44. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 161, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duex, J.; Theodorescu, D. CD44 in Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickeler, E.; Vogl, F.; Denkinger, T.; Möbus, V.; Kreienberg, R.; Runnebaum, I. Soluble CD44 splice variants and pelvic lymph node metastasis in ovarian cancer patients. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2000, 6, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainz, C.; Tempfer, C.; Winkler, S.; Sliutz, G.; Koelbl, H.; Reinthaller, A. Serum CD44 splice variants in cervical cancer patients. Cancer Lett. 1995, 90, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadducci, A.; Ferdeghini, M.; Fanucchi, A.; Annicchiarico, C.; Cosio, S.; Prontera, C.; Bianchi, R.; Genazzani, A.R. Serum assay of soluble CD44 standard (sCD44-st), CD44 splice variant v5 (sCD44-v5), and CD44 splice variant v6 (sCD44-v6) in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17, 4463–4466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kawano, T.; Yanoma, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Shiono, O.; Kokatu, T.; Kubota, A.; Furukawa, M.; Tsukuda, M. Evaluation of soluble adhesion molecules CD44 (CD44st, CD44v5, CD44v6), ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 as tumor markers in head and neck cancer. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2005, 26, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawano, T.; Yanoma, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Ozeki, A.; Kokatsu, T.; Kubota, A.; Furukawa, M.; Tsukuda, M. Soluble CD44 standard, CD44 variant 5 and CD44 variant 6 and their relation to staging in head and neck cancer. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2005, 125, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisterer, W.; Bechter, O.; Soderberg, O.; Nilsson, K.; Terol, M.; Greil, R.; Thaler, J.; Herold, M.; Finke, L.; Gunthert, U.; et al. Elevated levels of soluble CD44 are associated with advanced disease and in vitro proliferation of neoplastic lymphocytes in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leuk. Res. 2004, 28, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeimet, A.G.; Widschwendter, M.; Uhl-Steidl, M.; Muller-Holzner, E.; Daxenbichler, G.; Marth, C.; Dapunt, O. High serum levels of soluble CD44 variant isoform v5 are associated with favourable clinical outcome in ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1997, 76, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliutz, G.; Tempfer, C.; Winkler, S.; Kohlberger, P.; Reinthaller, A.; Kainz, C. Immunohistochemical and serological evaluation of CD44 splice variants in human ovarian-cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1995, 72, 1494–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Tsujitani, S.; Katano, K.; Ikeguchi, M.; Maeta, M.; Kaibara, N. Serum concentration of CD44 variant 6 and its relation to prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer 1998, 83, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sasaki, K.; Niitsu, N. Elevated serum levels of soluble CD44 variant 6 are correlated with shorter survival in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2000, 65, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapasso, S.; Garozzo, A.; Belfiore, A.; Allegra, E. Evaluation of the CD44 isoform v-6 (sCD44var, v6) in the saliva of patients with laryngeal carcinoma and its prognostic role. Cancer Biomark. 2016, 16, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhlin, O.W.; Cohen, M.B. Soluble forms of CD44 and CD54 (ICAM-1) cellular adhesion molecules are released by human prostatic cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 1996, 107, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.; Chan, C.; Yu, J.; He, M.; Choi, C.; Lam, J.; Wong, N. Development of CD44E/s dual-targeting DNA aptamer as nanoprobe to deliver treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nanotheranostics 2022, 6, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, D.; Denis, M.G.; Denis, M.; Blanchard, D.; Loirat, M.J.; Cassagnau, E.; Lustenberger, P. Soluble CD44: Quantification and molecular repartition in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 1995–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Faber, A.; Barth, C.; Hormann, K.; Kassner, S.; Schultz, J.D.; Sommer, U.; Stern-Straeter, J.; Thorn, C.; Goessler, U.R. CD44 as a stem cell marker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cema, I.; Dzudzilo, M.; Kleina, R.; Franckevica, I.; Svirskis, S. Correlation of Soluble CD44 Expression in Saliva and CD44 Protein in Oral Leukoplakia Tissues. Cancers 2021, 13, 5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarajan, P.; Shin, J.M.; Qian, X.; Matte, B.; Zhu, J.Y.; Kapila, Y.L. ADAM17-mediated CD44 cleavage promotes orasphere formation or stemness and tumorigenesis in HNSCC. Cancer Med. 2013, 2, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, D.; Sionov, R.V.; IshShalom, D. CD44: Structure, function, and association with the malignant process. Adv. Cancer Res. 1997, 71, 241–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jia, H.; Li, W.; Hou, Y.; Lu, S.; He, S. Screening and Identification of a Phage Display Derived Peptide That Specifically Binds to the CD44 Protein Region Encoded by Variable Exons. J. Biomol. Screen. 2016, 21, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ristamaki, R.; Joensuu, H.; Lappalainen, K.; Teerenhovi, L.; Jalkanen, S. Elevated serum CD44 level is associated with unfavorable outcome in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 1997, 90, 4039–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, I.; Kawano, Y.; Tsuiki, H.; Sasaki, J.; Nakao, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Suga, M.; Ando, M.; Nakajima, M.; Saya, H. CD44 cleavage induced by a membrane-associated metalloprotease plays a critical role in tumor cell migration. Oncogene 1999, 18, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhner, B.; Li, W.; Hey, S.; Drobny, A.; Werny, L.; Becker-Pauly, C.; Lucius, R.; Zunke, F.; Linder, S.; Arnold, P. Proteolysis of CD44 at the cell surface controls a downstream protease network. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1026810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, O.; Saya, H. Mechanism and biological significance of CD44 cleavage. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, I.; Tsuiki, H.; Kenyon, L.; Godwin, A.; Emlet, D.; Holgado-Madruga, M.; Lanham, I.; Joynes, C.; Vo, K.; Guha, A.; et al. Proteolytic cleavage of the CD44 adhesion molecule in multiple human tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzmann, E.J.; Reategui, E.P.; Pedroso, F.; Pernas, F.G.; Karakullukcu, B.M.; Carraway, K.L.; Hamilton, K.; Singal, R.; Goodwinl, W.J. Soluble CD44 is a potential marker for the early detection of head and neck cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzmann, E.J.; Donovan, M.J. Effective early detection of oral cancer using a simple and inexpensive point of care device in oral rinses. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2018, 18, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, M.S.; Waldner, C.; Mongini, C.; Gravisaco, M.J.; Casanova, S.; Alvarez, E.; Hajos, S. Evaluation of soluble CD44 in patients with breast and colorectal carcinomas and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncol. Rep. 1999, 6, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.D.; GercelTaylor, C.; Gall, S.A. Expression and shedding of CD44 variant isoforms in patients with gynecologic malignancies. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 1996, 3, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Jansen, F.; Bokelmann, J.; Kolb, H. Soluble CD44 splice variants in metastasizing human breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 74, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.; Soares, J.; Gaiteiro, C.; Peixoto, A.; Lima, L.; Ferreira, D.; Relvas-Santos, M.; Fernandes, E.; Tavares, A.; Cotton, S.; et al. Glycan affinity magnetic nanoplatforms for urinary glycobiomarkers discovery in bladder cancer. Talanta 2018, 184, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcel, J.M.; Esquerda, A.; Rodriguez-Panadero, F.; Martinez-Iribarren, A.; Bielsa, S. The Use of Pleural Fluid sCD44v6/std Ratio for Distinguishing Mesothelioma from Other Pleural Malignancies. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, M.; Rzepakowska, A.; Kotula, I.; Demkow, U.; Niemczyk, K. Serum expression of Vascular Endothelial-Cadherin, CD44, Human High mobility group B1, Kallikrein 6 proteins in different stages of laryngeal intraepithelial lesions and early glottis cancer. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.H.; Raslan, S.; Samuels, M.A.; Iglesias, T.; Buitron, I.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S.; Thomas, G.R.; Califano, J.; Franzmann, E.J. Current salivary biomarkers for detection of human papilloma virus-induced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck-J. Sci. Spec. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3618–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hal, N.; Van Dongen, G.; Ten Brink, C.; Heider, K.; Rech-Weichselbraun, I.; Snow, G.; Brakenhoff, R. Evaluation of soluble CD44v6 as a potential serum marker for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 3534–3541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takigawa, N.; Segawa, Y.; Mandai, K.; Takata, I.; Fujimoto, N. Serum CD44 levels in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and their relationship with clinicopathological features. Lung Cancer 1997, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, G.; Kittl, E.; Pfandelsteiner, T.; Trieb, K.; Kotz, R. Concentration of soluble CD44 standard and soluble CD44 variant V5 in the serum of patients with malignant bone tumors. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2003, 40, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebudi, R.; Ayan, I.; Yasasever, V.; Demokan, S.; Gorgun, O. Are serum levels of CD44 relevant in children with pediatric sarcomas? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2006, 46, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, S.D.; Wolf, H.; Eiermann, W.; Kopp, R.; Rieskamp, G.; Schildberg, F.W.; Wilmanns, W. Soluble CD44 standard and v6 in serum of breast cancer patients: An indicator for therapy response. Eur. J. Cancer 1995, 31A, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittl, E.M.; Ruckser, R.; Selleny, S.; Samek, V.; Hofmann, J.; Huber, K.; Reiner, A.; Ogris, E.; Hinterberger, W.; Bauer, K. Evaluation of soluble CD44 splice variant v5 in the diagnosis and follow-up in breast cancer patients. Exp. Clin. Immunogenet. 1997, 14, 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sheen-Chen, S.M.; Chen, W.J.; Eng, H.L.; Sheen, C.C.; Chou, F.F.; Cheng, Y.F. Evaluation of the prognostic value of serum soluble CD 44 in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Investig. 1999, 17, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.M.; Jin, Q.R.; Ensor, J.; Boulbes, D.R.; Esteva, F.J. Serum CD44 levels and overall survival in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 130, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.A.; Lyu, N.; Wu, J.L.; Tang, H.L.; Xie, X.H.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Wei, W.D.; Xie, X.M. Breast cancer stem cell markers CD44 and ALDH1A1 in serum: Distribution and prognostic value in patients with primary breast cancer. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 3728–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, N.; Tsujitani, S.; Makino, M.; Maeta, M.; Kaibara, N. Soluble CD44 variant 6 as a prognostic indicator in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncology 1999, 56, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirghofran, Z.; Jalali, S.A.; Hosseini, S.V.; Vasei, M.; Sabayan, B.; Ghaderi, A. Evaluation of CD44 and CD44v6 in colorectal carcinoma patients: Soluble forms in relation to tumor tissue expression and metastasis. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2008, 39, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, C.; Moser, R.; Bauernhofer, T.; Wilders-Truschnig, M.; Samonigg, H.; Berghold, A.; Zatloukal, K. Soluble CD44 v5 and v6 in serum of patients with breast cancer. Correlation with expression of CD44 v5 and v6 variants in primary tumors and location of distant metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1998, 47, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harn, H.J.; Ho, L.I.; Shyu, R.Y.; Yuan, J.S.; Lin, F.G.; Young, T.H.; Liu, C.A.; Tang, H.S.; Lee, W.H. Soluble CD44 isoforms in serum as potential markers of metastatic gastric carcinoma. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1996, 22, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, A.; Hamed, F.; Raslan, H.; Fata, M.; Fayad, A. Diagnostic and prognostic value of cancer stem cell marker CD44 and soluble CD44 in the peripheral Blood of patients with oral Squamous cell carcinoma. Open Sci. J. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.; Ahire, C.; Dongre, H.; Joshi, S.; Jamghare, S.; Rane, P.; Kane, S.; Chaukar, D. Prognostic significance of elevated serum CD44 levels in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, E.; Trapasso, S.; La Boria, A.; Aragona, T.; Pisani, D.; Belfiore, A.; Garozzo, A. Prognostic role of salivary CD44sol levels in the follow-up of laryngeal carcinomas. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2014, 43, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasu, H.; Hibi, N.; Ohyashiki, J.H.; Hara, A.; Kubono, K.; Tsukada, Y.; Ando, K.; Iwama, H.; Hayashi, S.; Yahata, N.; et al. Serum soluble CD44 levels for monitoring disease states in acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Int. J. Oncol. 1998, 13, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, A.; Ishii, G.; Sugaya, Y.; Nishimura, M.; Saito, Y.; Harigaya, K. Potential use of serum CD44 as an indicator of tumour progression in acute leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. 1999, 17, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, S.; Hanagiri, T.; Taira, A.; Takenaka, M.; Oka, S.; Chikaishi, Y.; Uramoto, H.; So, T.; Yamada, S.; Tanaka, F. Immunohistochemical Expression and Serum Levels of CD44 as Prognostic Indicators in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncology 2016, 90, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebling, T.L.; Palechek, P.L.; Cohen, M.B. Immunohistochemical and soluble expression of CD44 in primary and metastatic human prostate cancers. Int. J. Oncol. 1997, 10, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Lein, M.; Weiss, S.; Schnorr, D.; Henke, W.; Loening, S. Soluble CD44 molecules in serum of patients with prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur. J. Cancer 1996, 32A, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lein, M.; Jung, K.; Weiss, S.; Schnorr, D.; Loening, S.A. Soluble CD44 variants in the serum of patients with urological malignancies. Oncology 1997, 54, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansauge, F.; Gansauge, S.; Rau, B.; Scheiblich, A.; Poch, B.; Schoenberg, M.H.; Beger, H.G. Low serum levels of soluble CD44 variant 6 are significantly associated with poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 1997, 80, 1733–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, R.; Classen, S.; Wolf, H.; Gholam, P.; Possinger, K.; Eiermann, W.; Wilmanns, W. Predictive relevance of soluble CD44v6 serum levels for the responsiveness to second line hormone- or chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 2995–3000. [Google Scholar]

- Stickeler, E.; Therasakvichya, S.; Moebus, V.J.; Kieback, D.G.; Runnebaum, I.B.; Kreienberg, R. Modulation of soluble CD44 concentrations by hormone and anti-hormone treatment in gynecological tumor cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 2001, 8, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.C.; Pramana, J.; van der Wal, J.E.; Lacko, M.; Peutz-Kootstra, C.J.; de Jong, J.M.; Takes, R.P.; Kaanders, J.H.; van der Laan, B.F.; Wachters, J.; et al. CD44 Expression Predicts Local Recurrence after Radiotherapy in Larynx Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5329–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.M.; Xing, R.D.; Zhang, F.M.; Duan, Y.Q. Serum soluble CD44v6 levels in patients with oral and maxillofacial malignancy. Oral Dis. 2009, 15, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresztes, D.; Csizmarik, A.; Nagy, N.; Modos, O.; Fazekas, T.; Bracht, T.; Sitek, B.; Witzke, K.; Puhr, M.; Sevcenco, S.; et al. Comparative proteome analysis identified CD44 as a possible serum marker for docetaxel resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weg-Remers, S.; Hildebrandt, U.; Feifel, G.; Moser, C.; Zeitz, M.; Stallmach, A. Soluble CD44 and CD44v6 serum levels in patients with colorectal cancer are independent of tumor stage and tissue expression of CD44v6. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998, 93, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristamaki, R.; Joensuu, H.; Salmi, M.; Jalkanen, S. Serum CD44 in malignant-lymphoma—An association with treatment response. Blood 1994, 84, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Tanizawa, A.; Fukumoto, Y.; Kikawa, Y.; Mayumi, M. Serum soluble CD44 in pediatric patients with acute leukemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 1999, 21, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquidi, V.; Kim, J.; Chang, M.R.; Dai, Y.F.; Rosser, C.J.; Goodison, S. CCL18 in a Multiplex Urine-Based Assay for the Detection of Bladder Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samy, N.; Abd El-Maksoud, M.D.; Mousa, T.E.; El-Mezayen, H.A.; Shaalan, M. Potential role of serum level of soluble CD44 and IFN-gamma in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med. Oncol. 2011, 28, S471–S475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRossi, G.; Marroni, P.; Paganuzzi, M.; Mauro, F.R.; Tenca, C.; Zarcone, D.; Velardi, A.; Molica, S.; Grossi, C.E. Increased serum levels of soluble CD44 standard but not of variant isoforms v5 and v6, in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 1997, 11, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, T.A.; Brooks, K.R.; Joshi, M.B.M.; Conlon, D.; Herndon, J.; Petersen, R.P.; Harpole, D.H. Serum protein expression predicts recurrence in patients with early-stage lung cancer after resection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2006, 81, 1982–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Pac-Sosinska, M.; Wiktor, K.; Paszkowski, T.; Maciejewski, R.; Torres, K. CD44, TGM2 and EpCAM as novel plasma markers in endometrial cancer diagnosis. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancic, M.M.; Megna, B.W.; Sverchkov, Y.; Craven, M.; Reichelderfer, M.; Pickhardt, P.J.; Sussman, M.R.; Kennedy, G.D. Noninvasive Detection of Colorectal Carcinomas Using Serum Protein Biomarkers. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 246, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodison, S.; Chang, M.R.; Dai, Y.F.; Urquidi, V.; Rosser, C.J. A Multi-Analyte Assay for the Non-Invasive Detection of Bladder Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goi, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Seki, K.; Nakagawara, G.; Urano, T.; Shiku, H.; Furukawa, K. Soluble protein encoded by CD44 variant exons 8-10 in the serum of patients with colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 1997, 84, 1452–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Gorai, S.; Devi, A.; Muthusamy, R.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M. Decoding of exosome heterogeneity for cancer theranostics. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.M.; Wang, C.H.; Zhu, H.H.; Wang, Y.P.; Wang, X.Y.; Cheng, X.D.; Ge, W.Z.; Lu, W.G. Exosome-mediated transfer of CD44 from high-metastatic ovarian cancer cells promotes migration and invasion of low-metastatic ovarian cancer cells. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Sawada, K.; Kinose, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Toda, A.; Nakatsuka, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Mabuchi, S.; Morishige, K.; Kurachi, H.; et al. Exosomes Promote Ovarian Cancer Cell Invasion through Transfer of CD44 to Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.H.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, G.Q.; Jia, Z.M.; Yu, Y.; Guo, J.W.; Hua, Y.T.; Guo, F.L.; Li, X.Q.; Zou, W.W.; et al. Enrichment of CD44 in Exosomes From Breast Cancer Cells Treated With Doxorubicin Promotes Chemoresistance. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, W.J.; Cao, X.L.; Gu, H.B.; Huang, J.Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Sha, X.; Shen, B.; Wang, T.; et al. Exosomal CD44 Transmits Lymph Node Metastatic Capacity Between Gastric Cancer Cells via YAP-CPT1A-Mediated FAO Reprogramming. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 860175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaridis, T.; Weller, J.; Bachurski, D.; Shakeri, F.; Schaub, C.; Hau, P.; Buness, A.; Schlegel, U.; Steinbach, J.P.; Seidel, C.; et al. A novel serum extracellular vesicle protein signature to monitor glioblastoma tumor progression. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichle, A.; Muqaku, B.; Eisinger, M.; Meier, S.M.; Tahir, A.; Pukrop, T.; Haferkamp, S.; Slany, A.; Gerner, C. Multi-omics analysis of serum samples demonstrates reprogramming of organ functions via systemic calcium mobilization and platelet activation in metastatic melanoma. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2017, 40, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rejeeth, C.; Pang, X.C.; Zhang, R.; Xu, W.; Sun, X.M.; Liu, B.; Lou, J.T.; Wan, J.J.; Gu, H.C.; Yan, W.; et al. Extraction, detection, and profiling of serum biomarkers using designed Fe3O4@SiO2@HA core-shell particles. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, O.; Shamsi, M. Transformative biomedical devices to overcome biomatrix effects. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 279, 117373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csosz, E.; Labiscsak, P.; Kallo, G.; Markus, B.; Emri, M.; Szabo, A.; Tar, I.; Tozser, J.; Kiss, C.; Marton, I. Proteomics investigation of OSCC-specific salivary biomarkers in a Hungarian population highlights the importance of identification of population-tailored biomarkers. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamayel, F.A.; Davoodi, P.; Dalband, M.; Hendi, S. Saliva as a Mirror of the Body Health. Avicenna J. Dent. Res. 2010, 2, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Toader, S.; Popa, C.; Sciuca, A.; Onofrei, B.; Branisteanu, D.; Costan, V.; Toader, M.; Hritcu, O. Saliva as a diagnostic tool: Insights into oral cancer biomarkers. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 16, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darai, E.; Bringuier, A.F.; Walker-Combrouze, F.; Feldmann, G.; Madelenat, P.; Scoazec, J.Y. Soluble adhesion molecules in serum and cyst fluid from patients with cystic tumours of the ovary. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 2831–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Rejeeth, C.; Xu, W.; Zhu, C.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Wan, J.J.; Jiang, M.W.; Qian, K. Label-Free Electrochemical Sensor for CD44 by Ligand-Protein Interaction. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 7078–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, B.B.; Fan, Q.; Cui, M.; Wu, T.T.; Wang, J.S.; Ma, H.M.; Wei, Q. Photoelectrochemical Biosensor for Sensitive Detection of Soluble CD44 Based on the Facile Construction of a Poly(ethylene glycol)/Hyaluronic Acid Hybrid Antifouling Interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 24764–24770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, R.A.; Jawaid, S.; Kalawar, N.H.; Tunesi, M.; Karakus, S.; Kilislioglu, A.; Willander, M. In-situ engineered MXene-TiO2/BiVO4 hybrid as an efficient photoelectrochemical platform for sensitive detection of soluble CD44 proteins. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 166, 112439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauta, P.R.; Hallur, P.M.; Chaubey, A. Gold nanoparticle-based rapid detection and isolation of cells using ligand-receptor chemistry. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoung, M.H.; Kim, T.K.; Shim, H.; Lee, S. Development of a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of CD44v3 using exon v3-and v6-specific monoclonal antibody pairs. J. Immunol. Methods 2016, 436, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekmurzayeva, A.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Myrkhiyeva, Z.; Nugmanova, A.; Shaimerdenova, M.; Ayupova, T.; Tosi, D. Label-free fiber-optic spherical tip biosensor to enable picomolar-level detection of CD44 protein. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekmurzayeva, A.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Assylbekova, N.; Myrkhiyeva, Z.; Dauletova, A.; Ayupova, T.; Shaimerdenova, M.; Tosi, D. Ultra-wide, attomolar-level limit detection of CD44 biomarker with a silanized optical fiber biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 208, 114217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikbayeva, Z.; Bekmurzayeva, A.; Myrkhiyeva, Z.; Assylbekova, N.; Atabaev, T.S.; Tosi, D. Green-synthesized gold nanoparticle-based optical fiber ball resonator biosensor for cancer biomarker detection. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 161, 109136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaimerdenova, M.; Ayupova, T.; Bekmurzayeva, A.; Sypabekova, M.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Tosi, D. Spatial-Division Multiplexing Approach for Simultaneous Detection of Fiber-Optic Ball Resonator Sensors: Applications for Refractometers and Biosensors. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltusheva, Z.U.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Tosi, D.; Gritsenko, L.V. Highly Sensitive Zinc Oxide Fiber-Optic Biosensor for the Detection of CD44 Protein. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, P.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Shan, L.; Zhang, C.; Feng, S. A novel sandwich electrochemical immunosensor utilizing customized template and phosphotungstate catalytic amplification for CD44 detection. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 160, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Yadav, S.; Sadique, M.; Khan, R. Electrochemically Exfoliated Graphene Quantum Dots Based Biosensor for CD44 Breast Cancer Biomarker. Biosensors 2022, 12, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.Y.; Wang, T.T.; Han, M.; Gu, Y.; Sun, G.C.; Peng, X.Y.; Shou, Q.H.; Song, H.P.; Liu, W.S.; Nian, R. Dual CEA/CD44 targeting to colorectal cancer cells using nanobody-conjugated hyaluronic acid-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles with pH- and redox-sensitivity. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 4707–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasunderam, A.; Thiviyanathan, V.; Tanaka, T.; Li, X.; Neerathilingam, M.; Lokesh, G.L.R.; Mann, A.; Peng, Y.; Ferrari, M.; Klostergaard, J.; et al. Combinatorial Selection of DNA Thioaptamers Targeted to the HA Binding Domain of Human CD44. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9106–9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, N.; Alshaer, W.; Allozi, O.; Mahafzah, A.; El-Khateeb, M.; Hillaireau, H.; Noiray, M.; Fattal, E.; Ismail, S. In Vitro Selection of Modified RNA Aptamers Against CD44 Cancer Stem Cell Marker. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2013, 23, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecak, A.; Skalniak, L.; Pels, K.; Ksiazek, M.; Madej, M.; Krzemien, D.; Malicki, S.; Wladyka, B.; Dubin, A.; Holak, T.A.; et al. Anti-CD44 DNA Aptamers Selectively Target Cancer Cells. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2020, 30, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Dai, Y.H.; Huang, X.; Li, L.L.; Han, B.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, J. Self-Assembling Peptide-Based Multifunctional Nanofibers for Electrochemical Identification of Breast Cancer Stem-like Cells. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 7531–7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Sun, X.; Liu, R.; Du, M.; Song, X.; Wang, S.; Hu, W.; Luo, X. A dual-responsive electrochemical biosensor based on artificial protein imprinted polymers and natural hyaluronic acid for sensitive recognition towards biomarker CD44. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 371, 132554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, S.; Shibuya, M.; Engbring, J.A.; Mochizuki, M.; Nomizu, M.; Kleinman, H.K. Identification of an active site on the laminin alpha 5 chain globular domain that binds to CD44 and inhibits malignancy. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 4810–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugarte-Berzal, E.; Bailón, E.; Amigo-Jiménez, I.; Albar, J.P.; García-Marco, J.A.; García-Pardo, A. A Novel CD44-binding Peptide from the Pro-Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Hemopexin Domain Impairs Adhesion and Migration of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 15340–15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Lee, S.C.; Ha, N.R.; Lee, S.J.; Yoon, M.Y. A novel peptide-based recognition probe for the sensitive detection of CD44 on breast cancer stem cells. Mol. Cell. Probes 2015, 29, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, T.; Chen, X.; Mao, X.; Yin, Y.; Chen, G. Amplified electrochemical detection of surface biomarker in breast cancer stem cell using self-assembled supramolecular nanocomposites. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 283, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cheng, K.; Chen, X.; Yang, R.; Lu, M.D.; Ming, L.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.Y.; Chen, D.Z. Determination of soluble CD44 in serum by using a label-free aptamer based electrochemical impedance biosensor. Anal. 2020, 145, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusupov, M.; Privat-Maldonado, A.; Cordeiro, R.M.; Verswyvel, H.; Shaw, P.; Razzokov, J.; Smits, E.; Bogaerts, A. Oxidative damage to hyaluronan-CD44 interactions as an underlying mechanism of action of oxidative stress-inducing cancer therapy. Redox Biol. 2021, 43, 101968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusche, D.F.; Wessels, D.J.; Reis, R.J.; Forrest, C.C.; Thumann, A.R.; Soll, D.R. New monoclonal antibodies that recognize an unglycosylated, conserved, extracellular region of CD44 in vitro and in vivo, and can block tumorigenesis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, J.; Clancy, R.; Dorchak, J.; Somiari, R.I.; Somiari, S.; Cutler, M.L.; Mural, R.J.; Shriver, C.D. DNA Aptamers against Exon v10 of CD44 Inhibit Breast Cancer Cell Migration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannas, P.; Hambach, J.; Koch-Nolte, F. Nanobodies and Nanobody-Based Human Heavy Chain Antibodies As Antitumor Therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousipour, S.; Mokarram, P.; Gargari, S.L.M.; Mostafavi-Pour, Z.; Barazesh, M.; Ramezani, A.; Ashktorab, H.; Mohammadi, S.; Ghavami, S. A Comparison Between Cell, Protein and Peptide-Based Approaches for Selection of Nanobodies Against CD44 from a Synthetic Library. Protein Pept. Lett. 2018, 25, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousipour, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Eftekhar, E.; Barazesh, M.; Morowvat, M.H. In Silico Investigation of Signal Peptide Sequences to Enhance Secretion of CD44 Nanobodies Expressed in Escherichia coli. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2021, 22, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, M. Modulation of CD44 activity by A6-peptide. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremmel, M.; Matzke, A.; Albrecht, I.; Laib, A.M.; Olaku, V.; Ballmer-Hofer, K.; Christofori, G.; Heroult, M.; Augustin, H.G.; Ponta, H.; et al. A CD44v6 peptide reveals a role of CD44 in VEGFR-2 signaling and angiogenesis. Blood 2009, 114, 5236–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turiel, E.; Martin-Esteban, A. Molecularly imprinted polymers-based microextraction techniques. Trac Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Xue, Z.; Mao, P.; Hu, J.; Xu, F.; Yao, C.; You, M. Emerging ELISA derived technologies for in vitro diagnostics. Trac Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 152, 116605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Xu, C.; Li, W.K.; Qiu, G.; He, B.; Ng, S.P.; Wu, C.M.L.; Lee, Y. In vivo liquid biopsy for glioblastoma malignancy by the AFM and LSPR based sensing of exosomal CD44 and CD133 in a mouse model. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 191, 113476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Q.; Yao, X.; Zhang, R.; Lang, O.Y.; Jiang, R.C.; Liu, X.F.; Song, C.X.; Zhang, G.W.; Fan, Q.L.; Wang, L.H.; et al. Cationic Conjugated Polymer/Fluoresceinamine-Hyaluronan Complex for Sensitive Fluorescence Detection of CD44 and Tumor-Targeted Cell Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 19144–19153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristamaki, R.; Joensuu, H.; Hagberg, H.; Kalkner, K.M.; Jalkanen, S. Clinical significance of circulating CD44 in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int. J. Cancer 1998, 79, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Kawakita, K.; Tominaga, A.; Kincade, P.W.; Matsukura, S. A role for CD44 in an antigen-induced murine model of pulmonary eosinophilia. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.C.; Wang, Q.; An, J.X.; Chen, J.; Li, X.L.; Long, Q.; Xiao, L.L.; Guan, X.Y.; Liu, J.G. CD44 Glycosylation as a Therapeutic Target in Oncology. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 883831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.M.S.; Mereiter, S.; Lonn, P.; Siart, B.; Shen, Q.; Heldin, J.; Raykova, D.; Karlsson, N.G.; Polom, K.; Roviello, F.; et al. Detection of post-translational modifications using solid-phase proximity ligation assay. New Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-benhaqy, S.; Ebeid, S.; AbdelMoheim, N.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, S.; Wezza, H. Soluble CD44 is a promising biomarker with a prognostic value in breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer Biomed. Res. 2021, 3, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, A.C.; Sugiyama, M.; Yoshida, K.; Sugino, T.; Borgya, A.; Goodison, S.; Matsumura, Y.; Tarin, D. Analysis of anomalous CD44 gene expression in human breast, bladder, and colon cancer and correlation of observed mRNA and protein isoforms. Am. J. Pathol. 1996, 149, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.P.; Tang, Y.F.; Xie, L.; Huang, A.P.; Xue, C.C.; Gu, Z.; Wang, K.Q.; Zong, S.Q. The Prognostic and Clinical Value of CD44 in Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastna, M.; Van Eyk, J.E. Secreted proteins as a fundamental source for biomarker discovery. Proteomics 2012, 12, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veyssiere, H.; Bidet, Y.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Radosevic-Robin, N.; Durando, X. Circulating proteins as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer. Clin. Proteom. 2022, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantara, C.; O’Connell, M.R.; Luthra, G.; Gajjar, A.; Sarkar, S.; Ullrich, R.L.; Singh, P. Methods for detecting circulating cancer stem cells (CCSCs) as a novel approach for diagnosis of colon cancer relapse/metastasis. Lab. Investig. 2015, 95, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Okumura, T.; Hirano, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Sekine, S.; Nagata, T.; Tsukada, K. Circulating tumor cells expressing cancer stem cell marker CD44 as a diagnostic biomarker in patients with gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauder, R.; Eisterer, W.; Thaler, J.; Gunthert, U. CD44 variant isoforms in non-hodgkins-lymphoma—A new independent prognostic factor. Blood 1995, 85, 2885–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.A.; Coward, P.Y.; Wilson, R.F.; Poston, R.N.; Odell, E.W.; Palmer, R.M. Serum concentration of total soluble CD44 is elevated in smokers. Biomarkers 2000, 5, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouschop, K.M.A.; Roelofs, J.; Sylva, M.; Rowshani, A.T.; ten Berge, I.J.M.; Weening, J.J.; Florquin, S. Renal expression of CD44 correlates with acute renal allograft rejection. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, J. Consideration of Sample Matrix Effects and “Biological” Noise in Optimizing the Limit of Detection of Biosensors. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3290–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silina, Y.; Morgan, B. LDI-MS scanner: Laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry-based biosensor standardization. Talanta 2021, 223, 121688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, P.; Moberg, A.; Murphy, M. Standards for reporting optical biosensor experiments (STROBE): Improving standards in the reporting of optical biosensor-based data in the literature. SLAS Discov. 2024, 29, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, J.; Katrivanos, E.; Leiman, L.; Abukhdeir, A.; Cardone, A.; Saritas-Yildirim, B.; Galamba, C.; Jankiewicz, C.; Rolfo, C.; Bhandari, D.; et al. BLOODPAC’s collaborations with European Union liquid biopsy initiatives. J. Liq. Biopsy 2025, 10, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.P.; Chen, J. Prognostic significance of CD24 and CD44 in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2017, 32, E75–E82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, T.; Di, G.; Shen, Z.; Shao, Z.; Lu, J. The prognostic role of cancer stem cells in breast cancer: A meta-analysis of published literatures. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 122, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.J.; Chen, D.D.; Li, Z.Q.; Yang, Y.L.; Ma, Z.M.; Huang, G.H. Prognosis assessment of CD44(+)/CD24(-) in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.L.; Song, L.N.; Deng, Z.F.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.J. Prognostic value of CD44v6 expression in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotargets Ther. 2018, 11, 5451–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Liu, H.Y.; Zhang, Z.L.; Wang, F.; Wang, Q.Y.; Zhou, S.H.; Wang, S.Q. CD44 Expression Is Predictive of Poor Prognosis in Pharyngolaryngeal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2014, 232, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Q.; Zhou, J.D.; Lu, J.; Xiong, H.; Shi, X.L.; Gong, L. Significance of CD44 expression in head and neck cancer: A systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, W.W.; Li, P.H.; Tang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Q.; Xu, X.Y. Clinicopathological significance of cancer stem cell markers in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 10, 6138–6147. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, R.; Pandiar, D.; Ramani, P.; Ramalingam, K.; Jayaraman, S. Utility of CD44/CD24 in the Outcome and Prognosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e42899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Wang, J.; Sun, G.; Cao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X. Prognostic significance of CD44V6 expression in osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2015, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Lun, L.M.; Zhu, B.Z.; Wang, Q.; Ding, C.M.; Hu, Y.L.; Huang, W.L.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, H. Diagnostic accuracy of CD44V6 for osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2016, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.W.; Gu, S.J.; Sun, Z.Z.; Rui, Y.J.; Wang, J.B.; Lu, Y.; Li, H.F.; Xu, K.L.; Sheng, P. Prognostic role of CD44 expression in osteosarcoma: Evidence from six studies. Diagn. Pathol. 2014, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dong, L.P.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, C.H. Role of cancer stem cell marker CD44 in gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 5059–5066. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.L.; Yu, K.; Teng, Z.; Zheng, G.L.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.P.; Cui, L.; Yu, X.S. CD44 family proteins in gastric cancer: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 3595-U1695. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Fu, Z.Y.; Xu, S.J.; Xu, Y.; Xu, P.F. The prognostic value of CD44 expression in gastric cancer: A meta-Analysis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2014, 68, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Wu, J.R.; Lai, X.; Ai, H.Y.; Tao, Y.F.; Zhu, B.; Huang, L.S. CD44 and CD44v6 are Correlated with Gastric Cancer Progression and Poor Patient Prognosis: Evidence from 42 Studies. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 40, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.Y. Prognostic value of long noncoding RNAs in gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 4877–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Y.; Jiang, H. Prognostic role of the cancer stem cell marker CD44 in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.Y.; Gu, C.L.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, M.X.; Fan, W.S.; Han, W.D.; Meng, Y.G. The prognostic value and clinicopathological significance of CD44 expression in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 294, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, D.B.; Zhang, X.Z. CD44 expression and its clinical significance in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11, 5350–5358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wu, T.; Lu, D.; Zhen, J.T.; Zhang, L. CD44 overexpression related to lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2018, 33, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.T.; Ma, X.; Chen, L.Y.; Gu, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ouyang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Huang, Q.B.; Zhang, X. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Naor, D.; Nedvetzki, S.; Golan, I.; Melnik, L.; Faitelson, Y. CD44 in cancer. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2002, 39, 527–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittl, E.M.; Ruckser, R.; RechWeichselbraun, I.; Hinterberger, W.; Bauer, K. Significant elevation of tumour-associated isoforms of soluble CD44 in serum of normal individuals caused by cigarette smoking. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1997, 35, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schlosser, W.; Gansauge, F.; Schlosser, S.; Gansauge, S.; Beger, H.G. Low serum levels of CD44, CD44v6, and neopterin indicate immune dysfunction in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 2001, 23, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, K.; Sato, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Takehara, K. Elevated levels of circulating CD44 in patients with systemic sclerosis: Association with a milder subset. Rheumatology 2002, 41, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kaburaki, T.; Mori, Y.; Fujimura, S.; Kawashima, H.; Yoshida, A.; Numaga, J.; Fujino, Y.; Araie, M. Soluble CD44 levels in sera of the patients with sarcoidosis uveitis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 5102. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.R.; Gao, J.L.; Lian, X.; Wang, Y.T. The clinicopathological and prognostic value of CD44 expression in bladder cancer: A study based on meta-analysis and TCGA data. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Song, X.H.; Liu, J.; Li, S.Z.; Gao, W.Q.; Qiu, M.X.; Yang, C.J.; Ma, Y.M.; Chen, Y.H. Expression of CD44 and the survival in glioma: A meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20200520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.X.; Ishi, Y.; Motegi, H.; Okamoto, M.; Ou, Y.F.; Chen, J.W.; Yamaguchi, S. Overexpression of CD44 is associated with a poor prognosis in grade II/III gliomas. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2019, 145, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhao, W.; Shao, W. Prognostic value of CD44 and CD44v6 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: Meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 7383–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.K.; Tan, Y. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-mosawi, A.K.M.; Cheshomi, H.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Matin, M.M. Prognostic and Clinical Value of CD44 and CD133 in Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 19, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; zur Hausen, A.; Watermann, D.O.; Stamm, S.; Jager, M.; Gitsch, G.; Stickeler, E. Increased soluble CD44 concentrations are associated with larger tumor size and lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 134, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andratschke, M.; Chaubal, S.; Pauli, C.; Mack, B.; Hagedorn, H.; Wollenberg, B. Soluble CD44v6 is not a sensitive tumor marker in patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2005, 25, 2821–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke, L.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, C. Snail Represses the Splicing Regulator Epithelial Splicing Regulatory Protein 1 to Promote Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 36435–36442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapudom, J.; Ullm, F.; Martin, S.; Kalbitzer, L.; Naab, J.; Moller, S.; Schnabelrauch, M.; Anderegg, U.; Schmidt, S.; Pompe, T. Molecular weight specific impact of soluble and immobilized hyaluronan on CD44 expressing melanoma cells in 3D collagen matrices. Acta Biomater. 2017, 50, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.M.; Teng, E.; Chong, H.S.; Lopez, K.A.P.; Tay, A.Y.L.; Salto-Tellez, M.; Shabbir, A.; So, J.B.Y.; Chan, S.L. CD44v8-10 Is a Cancer-Specific Marker for Gastric Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2630–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, L.L.; Hurme, S.; Maula, S.M.; Alanen, K.; Grénman, R.; Kinnunen, I.; Ventelä, S. Significance of site-specific prognosis of cancer stem cell marker CD44 in head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Tabanera, E.; de Mera, R.; Alonso, J. CD44 In Sarcomas: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 909450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Liao, C.C.; Chow, N.H.; Huang, L.L.H.; Chuang, J.I.; Wei, K.C.; Shin, J.W. Whether CD44 is an applicable marker for glioma stem cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 4785–4806. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wu, R.R.; Lv, L.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.Y.; Hao, Q.L.; Li, W. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 3632–3646. [Google Scholar]

- Yasasever, Y.; Tas, F.; Duranyildiz, D.; Camlica, H.; Kurul, S.; Dalay, N. Serum levels of the soluble adhesion molecules in patients with malignant melanoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2000, 6, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, A. The Diagnostic Utility of Cancer Stem Cell Marker CD44 in Early Detection of Oral Cancer. Master’s Thesis, University Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Name of the Protein in the Current Work | Description | Name of the Protein in Other Works | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| solCD44std | - Standard form of CD44 (wild type) - Non variant | - standard CD44 - CD44std - CD44standard - sCD44std - CD44s - sCD44-st - sCD44st - sCD44s | [30,31,32,33,34,35] |

| solCD44v1-v10 | - Soluble variants (isoforms) of the CD44 protein, which arise due to alternative splicing of variable exons in the mRNA of CD44; - v1 (variant 1) refers to isoform 1 | - CD44v1 - sCD44v5 (sCD44-v5) - sCD44var v6 - isoform 1 - CD44E (CD44v8-10) | [30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] |

| solCD44 | One of the following: - general idea of soluble CD44 protein in serum (circulatory), saliva, urine, or other biological fluids - Total soluble CD44 (standard and isoforms); - When protein type (standard or isoform) is not specified in the works: the standard form or variant form is not shown. | - sCD44 - solCD44 - SolCD44 - circulating CD44 - soluble CD44 | [1,18,36,43,44,45] |

| Type of Probe/Ligand | Advantages | Examples of Ligands | Use in Assays | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble | on Cells or Tissues | |||

| HA | - Natural ligand - Also used as an anti-fouling agent | (C14H21NO11)n | - Biosensors [115,116,117] | - Colorimetric assay using nanoparticles [118] |

| Antibodies | - A well-known ligand - Commercially available - Some were shown to inhibit oncogenesis | - More than 140 are known - P4G9, P3D2, P3A7, P3G4 - C44Mab−46 (IgG1, kappa) | - All commercial ELISA kits - Customized ELISA [119] - Optical fiber biosensors [120,121,122,123,124] -Electrochemical [125,126] - OncAlert™ kit [45] | - Western blot analysis - FACS - IHC |

| Nanobodies | - Small size - High stability - High solubility - Excellent tissue penetration in vivo - Chemical conjugation at a specific site (e.g., to drugs) | - 11C12 | - NF | - Nanoparticle-based assay [127] |

| Nucleic acid aptamers | - High chemical stability - Flexibility of modification - Selected in vitro - Ease of synthesis | - TA1 [128]—thioaptamer that binds the HA binding domain - Apt1 [129] - s5 [130]—binds the HA binding domain - AS1411 [131] - Dual-responsive aptamer [132] | - Electrochemical biosensors [137] | - Sensing platform for cells [119] - FACS [129] - Fluorescent microscopy [129] |

| Peptides | - Selected in vitro - Stability - Low molecular weight | - A5G27 [133] - P3 and P6 [134] - PDL-P7, P6 (dual peptide) [135] | - NF | - Polymeric target recognition system [135] - IHC [48,135] - FACS [135] - Electro-chemical biosensors [136] |

| Molecularly imprinted polymers | - Great selectivity - High capacity for recognition and capture (re-binding) - Stability (pH and temperature) | - Protein MIP [132] | - Electrochemical biosensor [132] | - NF |

| Criteria | CD44 Expressing Cells/Tissues | Soluble CD44 Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Availability |

|

|

| Systemic reviews and meta-analysis |

|

|

| Available assays |

|

|

| Commercially available assays |

|

|

| Main strengths |

|

|

| Main drawbacks |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Myrkhiyeva, Z.; Nurlankyzy, M.; Berikkhanova, K.; Baimagambet, Z.; Bissen, A.; Bikhanov, N.; Tan, C.K.L.; Tosi, D.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Bekmurzayeva, A. Digging into the Solubility Factor in Cancer Diagnosis: A Case of Soluble CD44 Protein. Biosensors 2025, 15, 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120796

Myrkhiyeva Z, Nurlankyzy M, Berikkhanova K, Baimagambet Z, Bissen A, Bikhanov N, Tan CKL, Tosi D, Ashikbayeva Z, Bekmurzayeva A. Digging into the Solubility Factor in Cancer Diagnosis: A Case of Soluble CD44 Protein. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):796. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120796

Chicago/Turabian StyleMyrkhiyeva, Zhuldyz, Marzhan Nurlankyzy, Kulzhan Berikkhanova, Zhanas Baimagambet, Aidana Bissen, Nurzhan Bikhanov, Christabel K. L. Tan, Daniele Tosi, Zhannat Ashikbayeva, and Aliya Bekmurzayeva. 2025. "Digging into the Solubility Factor in Cancer Diagnosis: A Case of Soluble CD44 Protein" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120796

APA StyleMyrkhiyeva, Z., Nurlankyzy, M., Berikkhanova, K., Baimagambet, Z., Bissen, A., Bikhanov, N., Tan, C. K. L., Tosi, D., Ashikbayeva, Z., & Bekmurzayeva, A. (2025). Digging into the Solubility Factor in Cancer Diagnosis: A Case of Soluble CD44 Protein. Biosensors, 15(12), 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120796