Overview on the Sensing Materials and Methods Based on Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization

Abstract

1. Introduction

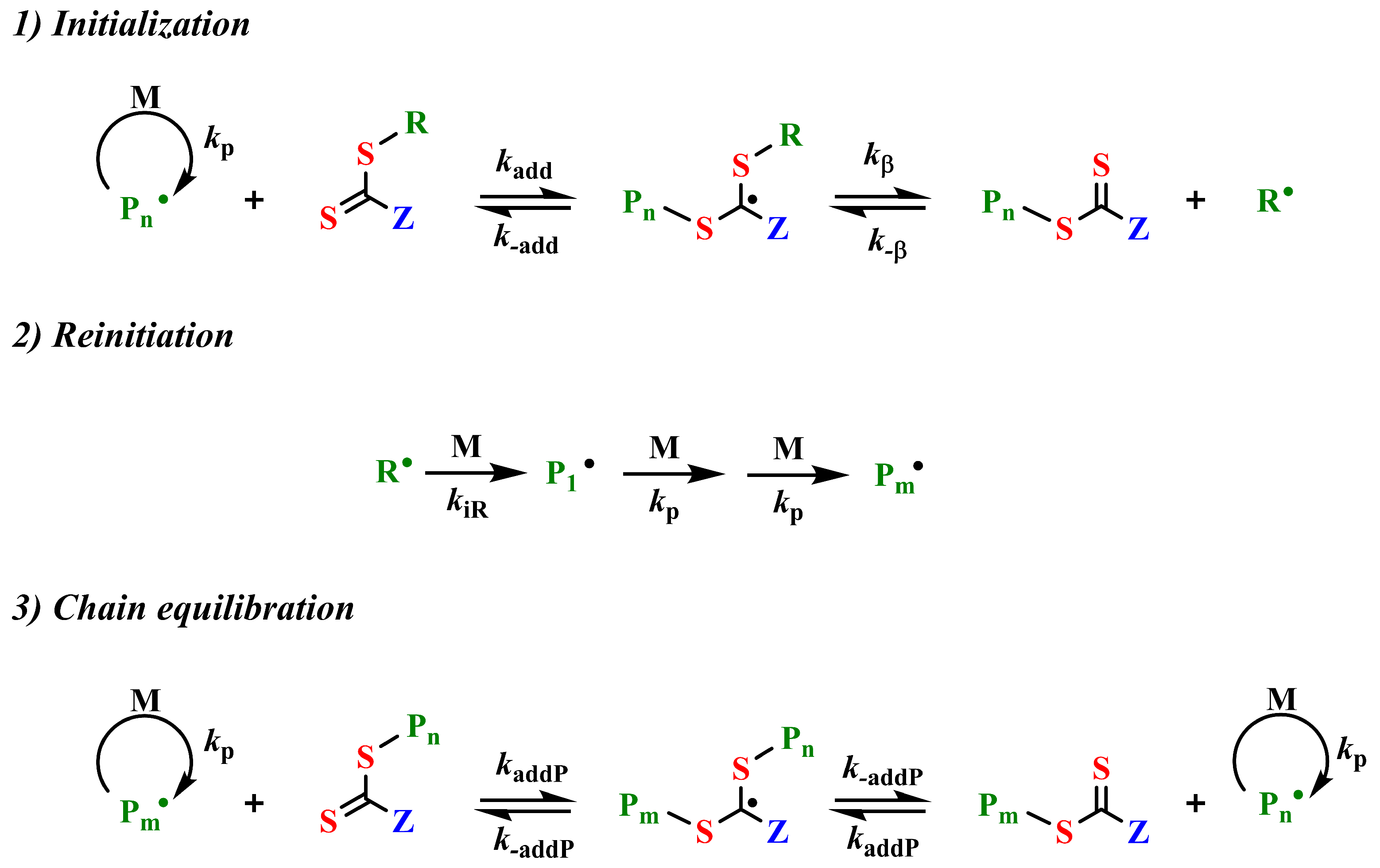

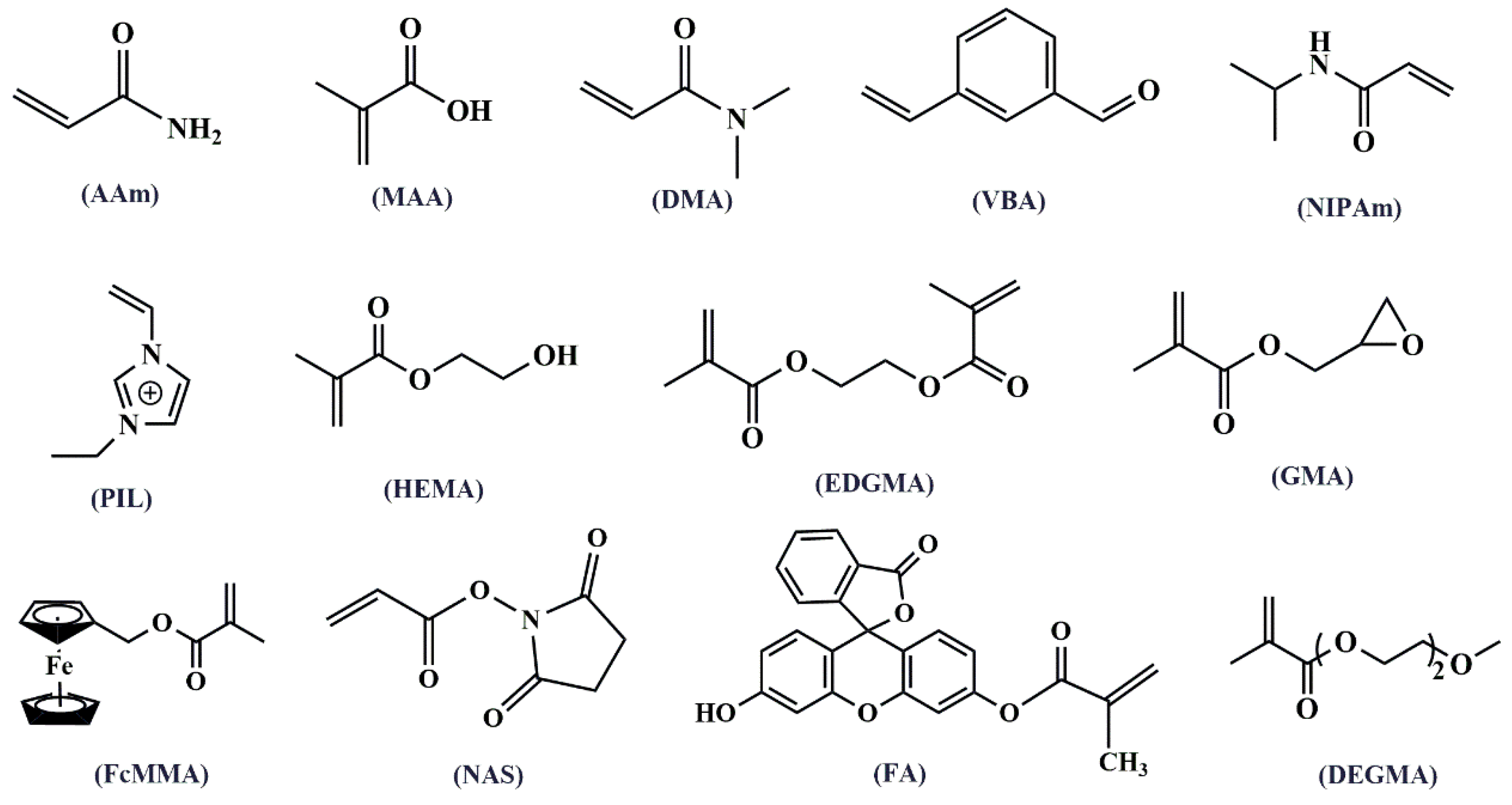

2. RAFT Polymerization: Mechanisms and Advantages

3. Polymer Architecture Design for Sensing

4. Target-Specific Sensing Applications

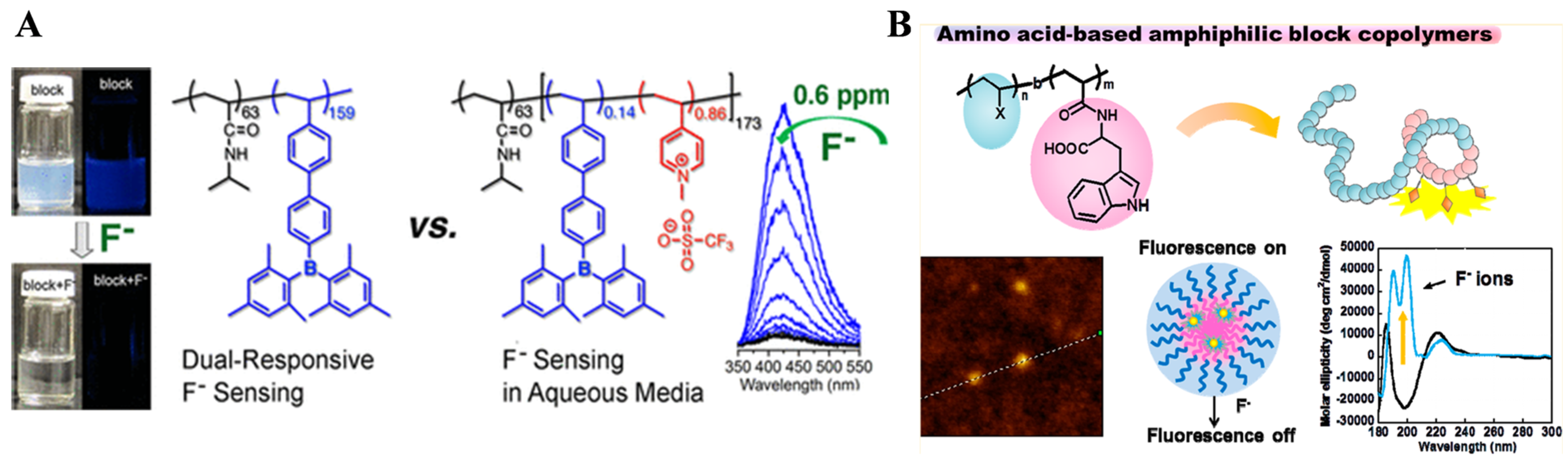

4.1. Polymeric Materials Prepared by RAFT Polymerization for Sensing of Ions

| Material | Ion | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BODIPY-derived polymer | Fe3+ | 1–15 μM | 1.2 μM | [30] |

| Naphthalene-derived polymer | Fe3+ | 0–15 μM | 1.82 nM | [32] |

| Azo-Schiff base polymer | Fe3+ | 0.1–1.3 mM | 0.1 mM | [33] |

| NBN-derived polymer | Fe3+, Cr3+ | 1–6.5 μM, 0–10 μM | 7.3 nM, 14.69 nM | [34] |

| Coumarin-derived β-CD | Fe3+ | 0–16 μM | 0.34 μM | [35] |

| Pyrene-derived polymer | Al3+ | 0–0.6 μM | 0.22 μM | [36] |

| Salicylaldehyde-derived polymer | Al3+, Zn2+ | – | 2.14 ppb, 8.71 ppb | [47] |

| Benzaldehyde and Rh6G-derived polymer | Al3+, Fe3+ | – | 30 nM, 5.95 nM | [37] |

| Quinoline based polymer | Zn2+ | – | 3 nM | [46] |

| BODIPY-derived polymer | Hg2+ | 0–20 µM | 1.1 µM | [39] |

| BODIPY-derived polymer | Hg2+ | 0–2 μM | 0.37 μM | [44] |

| BODIPY-derived chitosan | Hg2+, Hg+ | 0–20 μM | 0.61 μM, 0.47 μM | [43] |

| Fe3O4@SiO2-PAP | Cu2+ | 0.1–2 µg/mL | 0.125 µM | [45] |

| GO-LP/PMAM | Cu2+ | 0.25–2 mM | 0.19 mM | [40] |

| Polymeric micelles | Cu2+ | 33–100 μM | – | [48] |

| Naphthalimide-derived chitosan | Cr3+, Cu2+ | 0–10 μM | 44.6 nM, 54.5 nM | [42] |

| ZnO QDs | Cr6+ | – | 1.13 µM | [41] |

| Colorimetric polymer probe | Cu2+ | – | 0.18 nM | [54] |

| Ion imprinted polymer paper | Cd2+ | 1–100 ng/mL | 0.4 ng/mL | [55] |

| Polymer-AuNPs | Fe3+ | 8–25 mM | – | [56] |

| Hemicyanine-based probe | CN− | 7–140 μM | 2.24 μM | [57] |

4.2. Polymeric Materials Prepared by RAFT Polymerization for Sensing of Small Molecules

4.2.1. Electrochemical Sensing of Small Molecules

| Material | Analyte | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block copolymers | Dopamine | 5 × 10−2–1.5 mM | 0.05 mM | [77] |

| Triblock copolymers | Syringic acid | 1.5–15 µg/mL | 0.44 µg/mL | [78] |

| GluOxENs/PB | Glutamate | 3.25–250 μM | 0.96 μM | [79] |

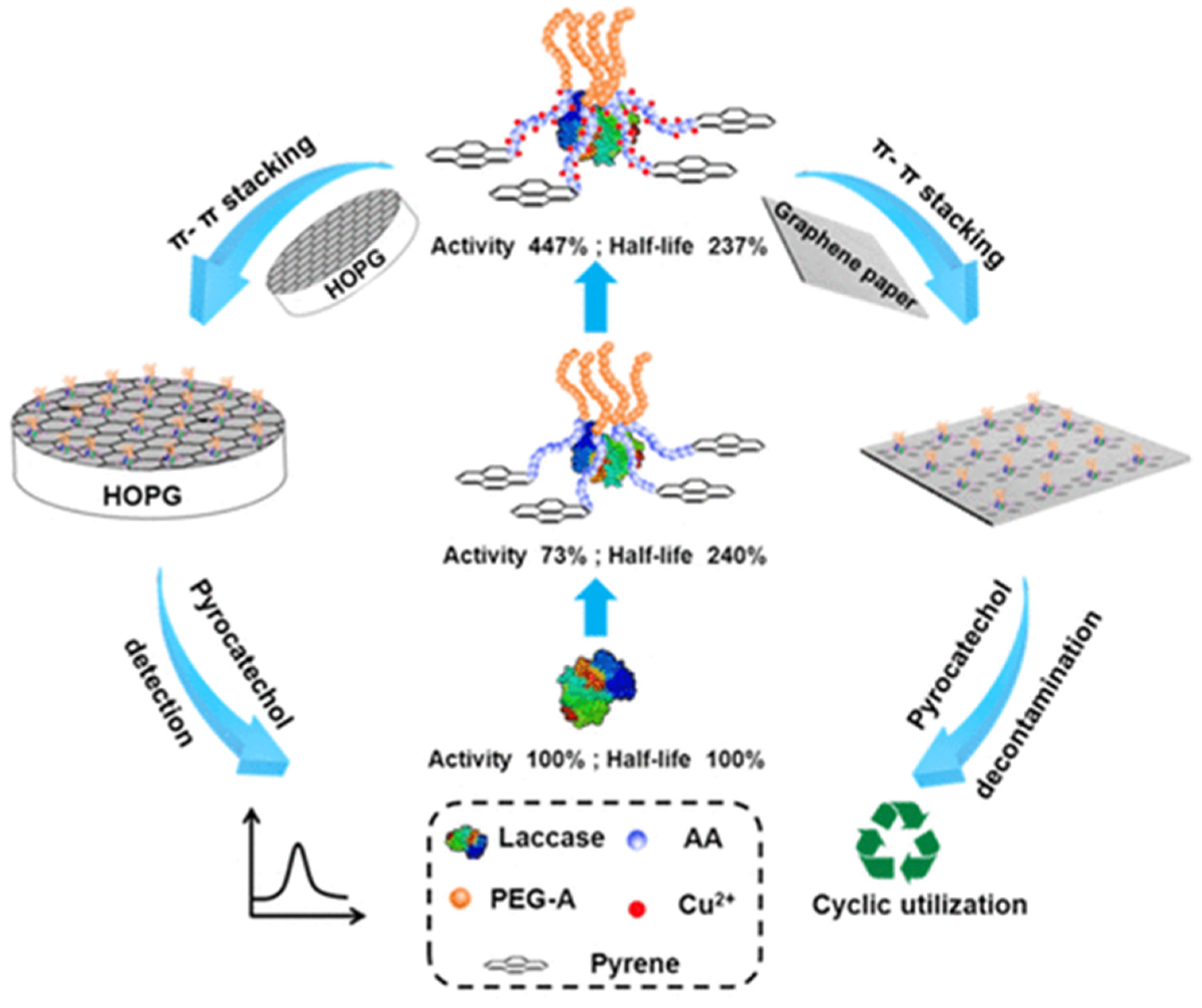

| Laccase/polymers | Pyrocatechol | 5 × 10−5–1 mM | 50 nM | [81] |

| MWCNTs@ZnO/PMAEFc | Aspartame | 10−3–10 nM | 1.35 nM | [80] |

| AuNPs@MIPs | Fenitrothion | 10−2–5 μM | 8 nM | [83] |

| MWCNTs@MIPs | Brucine | 0.6–5.0 μM | 2 nM | [84] |

| MWCNTs@MIPs | Imidacloprid | 0.2–24 μM | 0.08 μM | [85] |

| Fe3O4-MIP@rGO | 17β-Estradiol | 5 × 10−2–10 μM | 0.819 nM | [86] |

| GO@MIPs | Glucose | 1.5–1500 μM | 5.88 μM | [87] |

| GO@MIPs | Methylparathion | 0.2–200 ng/mL | 4.25 ng/mL | [88] |

| Au@Fe3O4@rGO-MIPs | Ractopamine | 2–100 nM | 0.02 nM | [89] |

| MSMIP/rGO | Tetracycline | 1.6–88 nM | 0.916 nM | [90] |

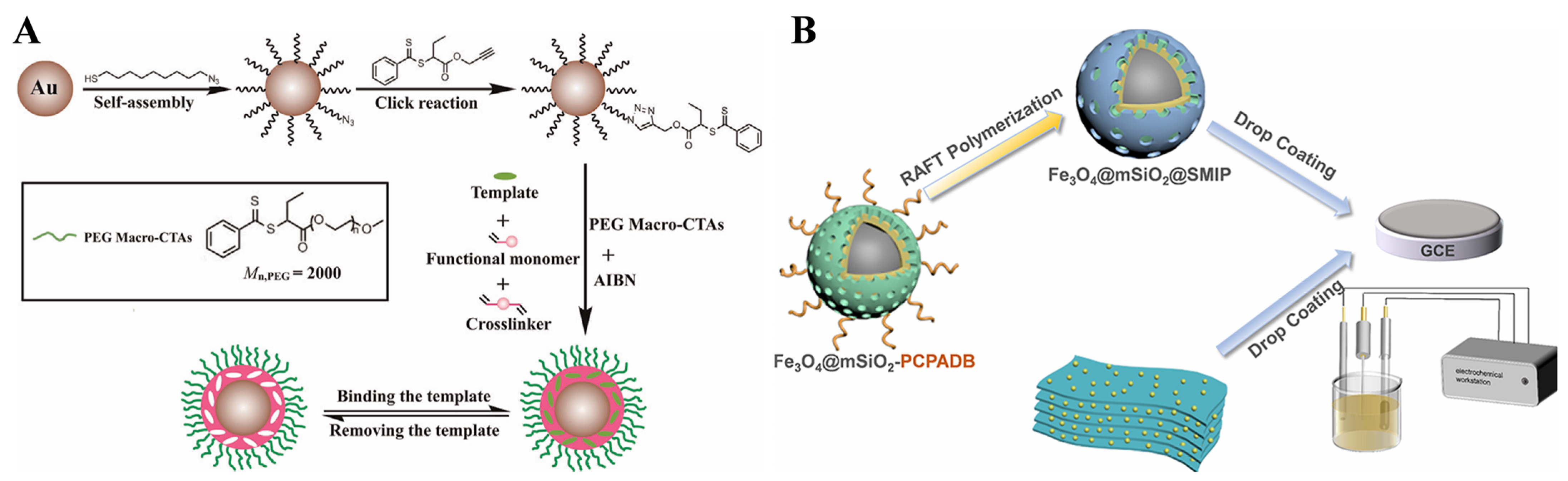

| Fe3O4@mSiO2@SMIP | TBBPA | 1–4500 nM | 0.83 nM | [91] |

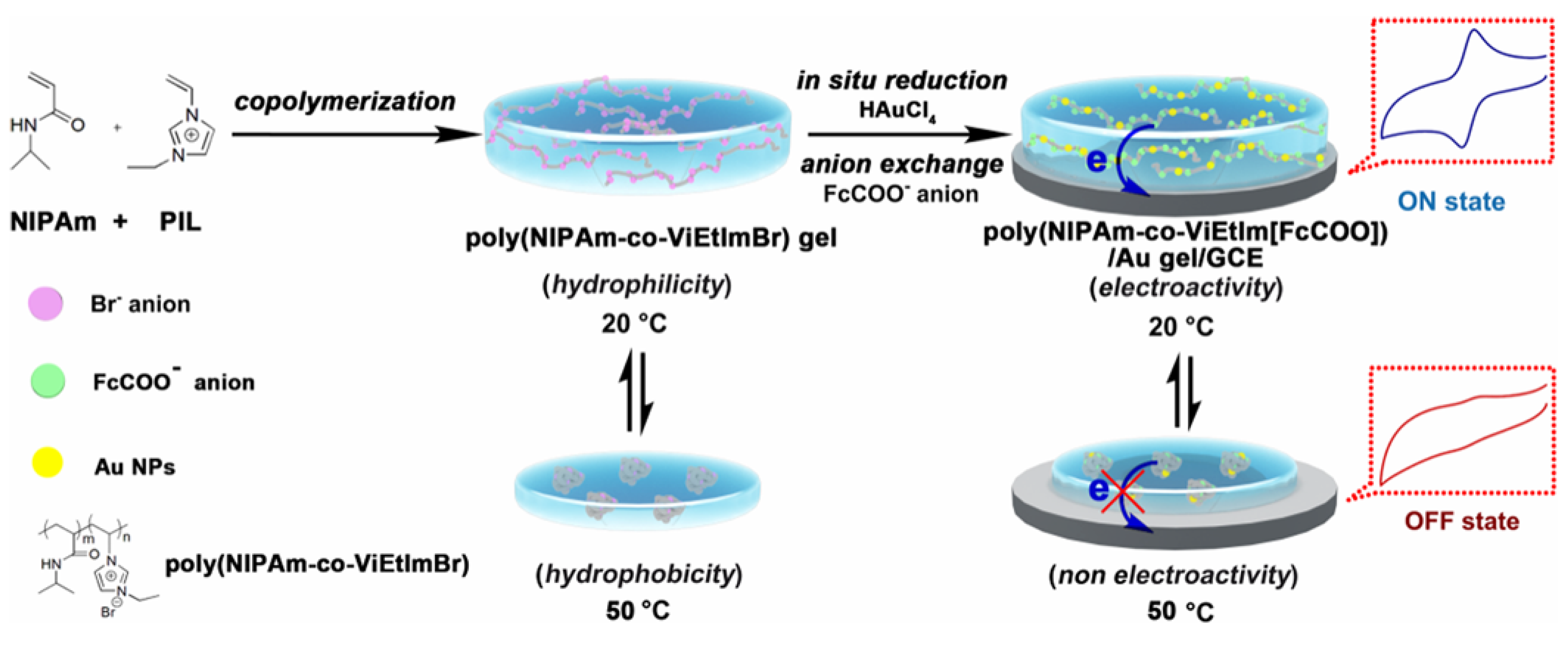

| Polymer/AuNPs gel | Ascorbic acid | 0.1–25.8 mM | 92.9 μM | [95] |

| Ru@pyrene-PSS | Tripropylamine | 1–5000 μM | 0.1 nM | [98] |

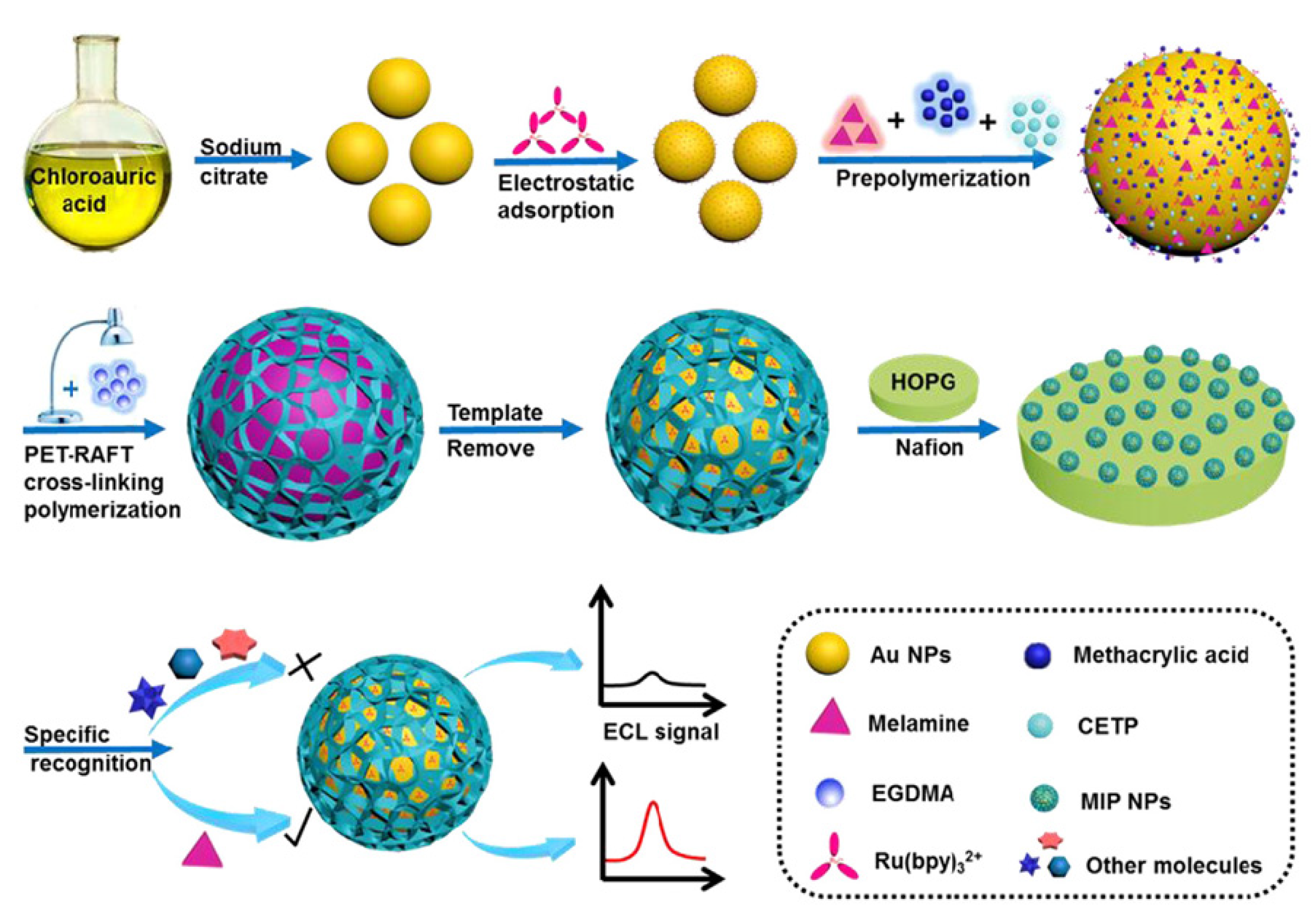

| Ru@AuNPs@MIPs | Melamine | 5 × 10–7–5 μM | 0.1 pM | [99] |

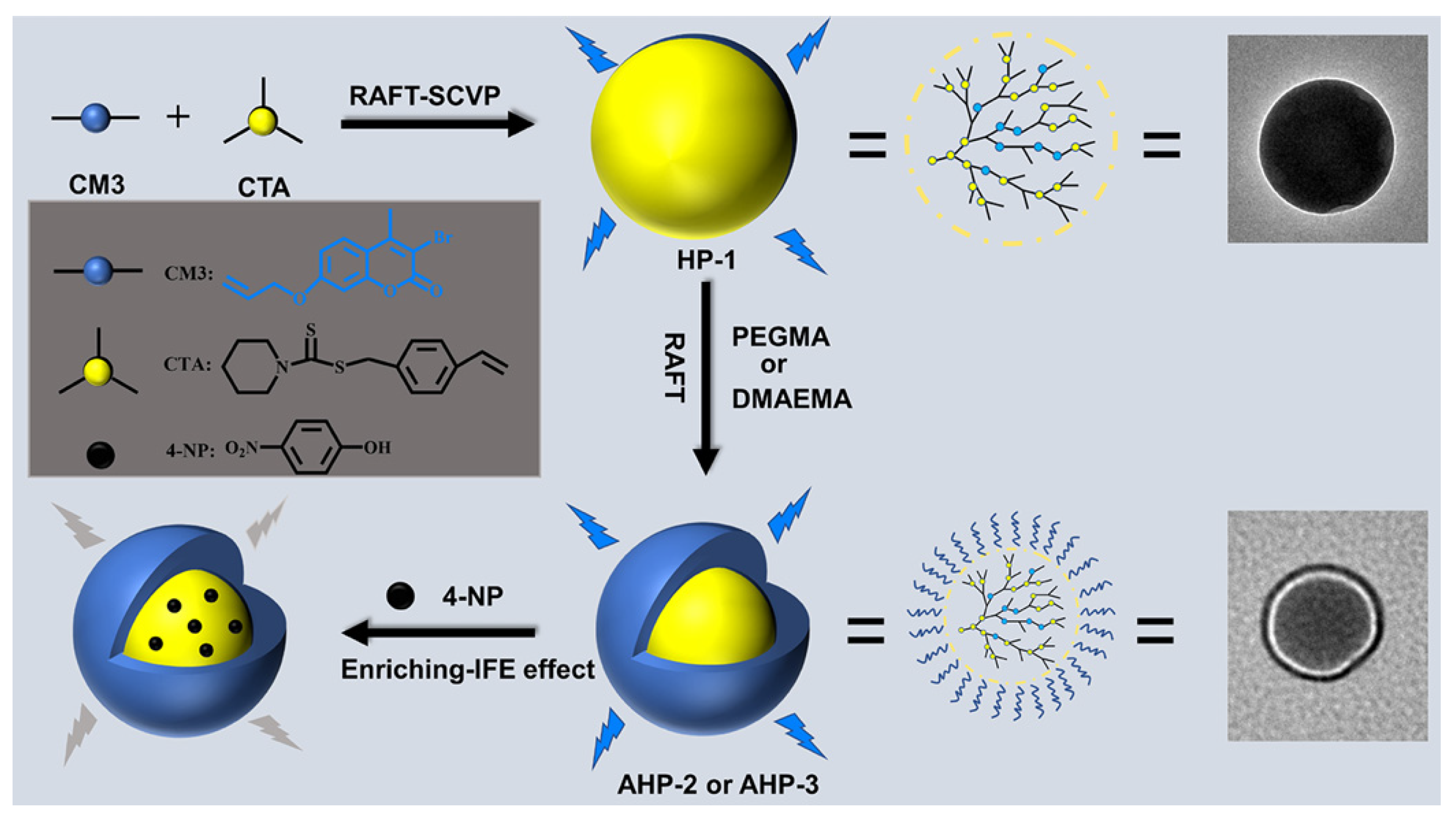

4.2.2. Optical Sensing of Small Molecules

| Method/Material | Analyte | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence/Cellulose | 4-nitrophenol | 10–10 μM | 0.46 μM | [101] |

| Fluorescence/Chitosan | 4-nitrophenol | 0–10 μM | 54 nM | [102] |

| Fluorescence/Polyampholyte | CS2 | 0–124 mM | 123 µM | [103] |

| Fluorescence/MIP NPs | tetracycline | 0.5–20 μM | 0.26 μM | [105] |

| Fluorescence/MIP-QDs | folic acid | 5 × 10−2–10 μM | 25 nM | [106] |

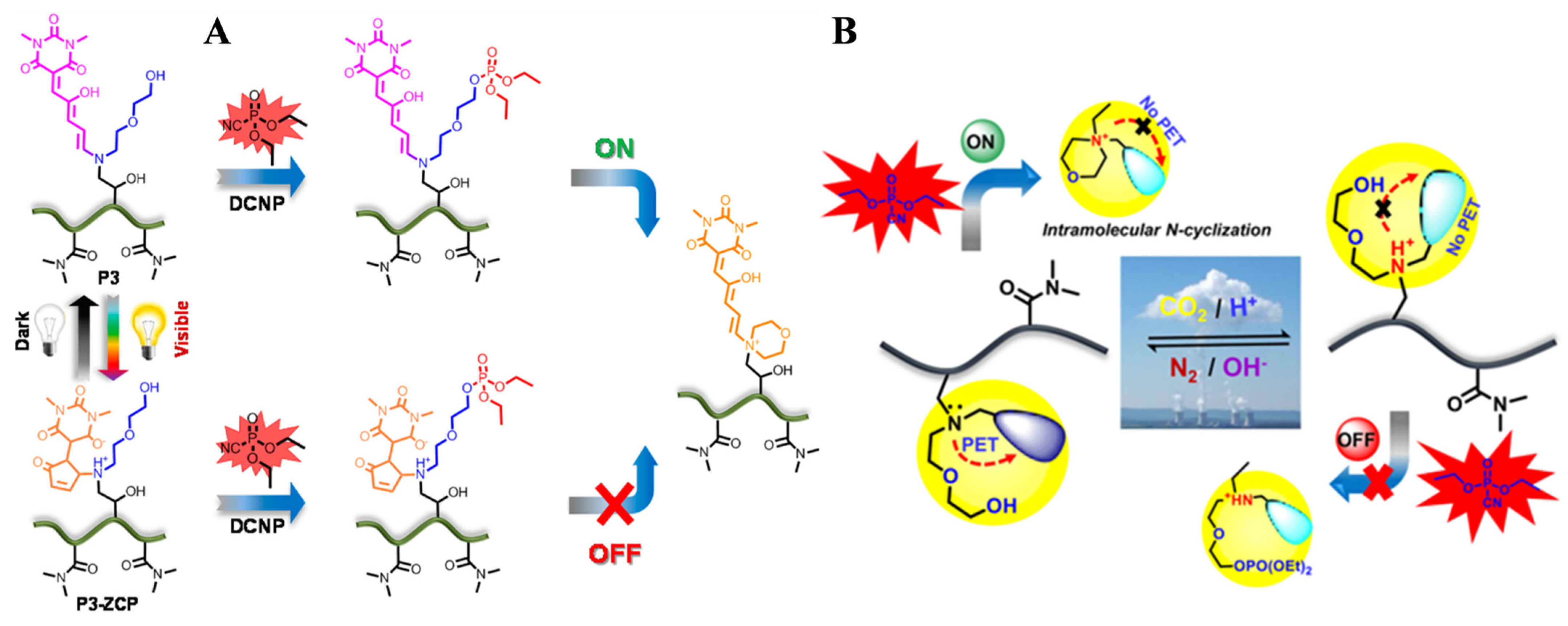

| Color/Polymer | DCNP | 0.5–6 mM | 1 mM | [107] |

| Fluorescence/Polymer | DCNP | 0–0.6 mM | 0.1 mM | [108] |

| Fluorescence/Polymer | 4 nitrophenol | 0.1–18 mM | 0.59 μM | [109] |

| Fluorescence/Copolymer | TNP | 0–80 ppm | 19 ppm | [114] |

| Fluorescence/GO@ZnS NPs | TNP | 0.2–16 nM | 4.4 nM | [115] |

| Fluorescence/MIP-GO | histamine | 0.1–1000 M | 25 nM | [116] |

| Fluorescence/Alq3-GO | TNP | 0.12–2 nM | 2.38 nM | [117] |

| Fluorescence/PBA polymer | HQ | 5 × 10−2–3 ppm | – | [112] |

| color /PBA polymer | glucose | 3–30 mM | 3 mM | [113] |

| SERS/Polymer | aflatoxin B1 | – | 10 ppb | [118] |

4.3. Polymeric Materials Prepared by RAFT Polymerization for Bioimaging

5. Biosensors by the Signal Amplification of RAFT Polymerization Technique

5.1. Electrochemical Biosensors Based on RAFT Polymerization for Signal Amplification

5.1.1. Thermal SI-RAFT Polymerization for Signal Amplification

5.1.2. eRAFT Polymerization for Signal Amplification

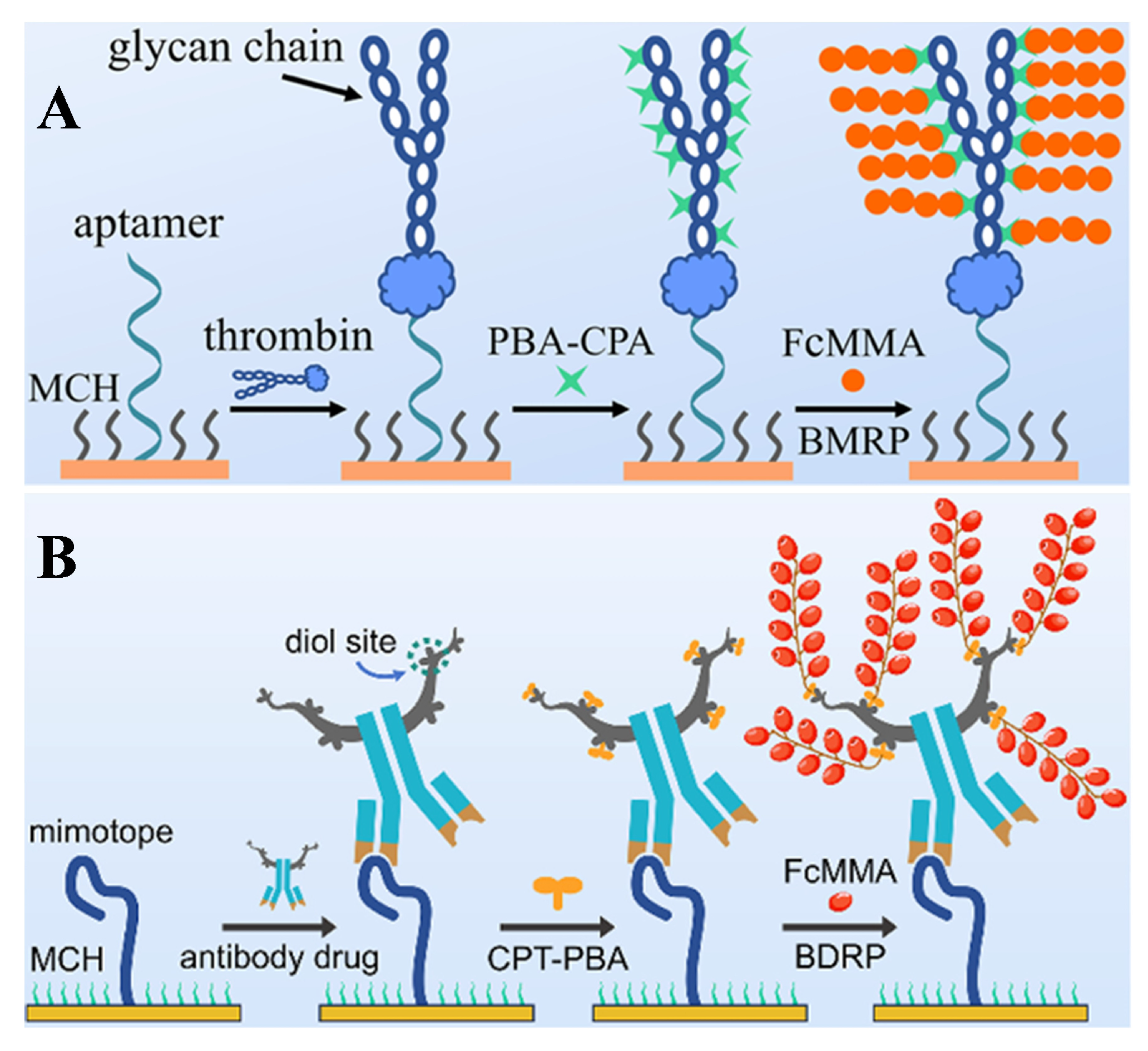

5.1.3. Bioinspired eRAFT Polymerization for Signal Amplification

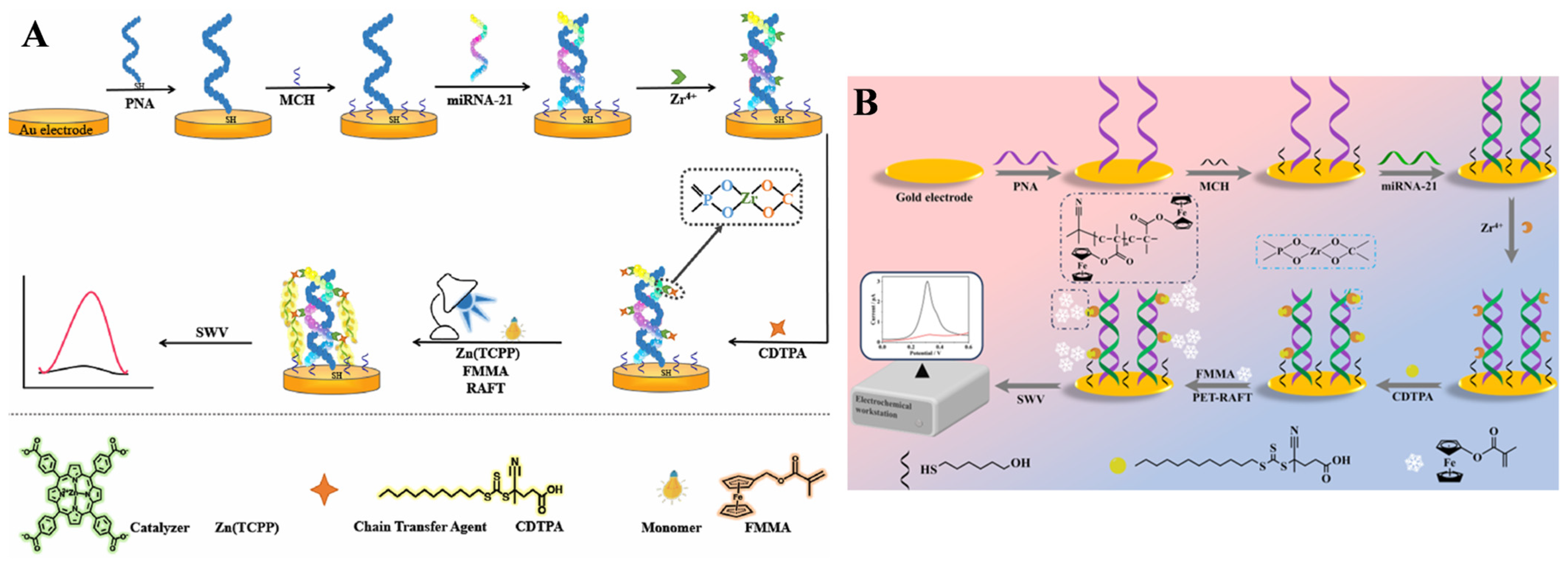

5.1.4. PET-RAFT Polymerization for Signal Amplification

| RAFT Method | Analyte | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI-RAFT | DNA | 10−5–10 pM | 3.2 aM | [148] |

| DNA | 10−2–10 pM | 1.51 aM | [149] | |

| DNA | 10−7–1 nM | 0.89 aM | [150] | |

| DNA | 10−6–10 pM | 0.487 aM | [151] | |

| DNA | 10–106 aM | 5.6 aM | [152] | |

| miRNA-21 | 10−5–1 pM | 0.21 aM | [153] | |

| PKA | 0−140 mU/mL | 1.05 mU/mL | [154] | |

| PKA | 10−7–10−2 mU/mL | 3.4 mU/mL | [155] | |

| thrombin | 10−250 μU/mL | 2.7 μU/mL | [156] | |

| cocaine | 10−2–1000 ng/mL | 3 pg/mL | [157] | |

| CYFRA21-1 | 0.5−10,000 fg/mL | 0.14 fg/mL | [158] | |

| RdRP | 5–500 aM | 0.8 aM | [159] | |

| cTnI | 10−3–1000 ng/mL | 10.83 fg/mL | [160] | |

| eRAFT | DNA | 10−5–10 pM | 4.1 aM | [161] |

| PKA | 0−140 mU/mL | 1.02 mU/mL | [162] | |

| MMP-2 | 10−3–1 ng/mL | 0.27 pg/mL | [163] | |

| DNA | 10−5–1 pM | 5.4 aM | [164] | |

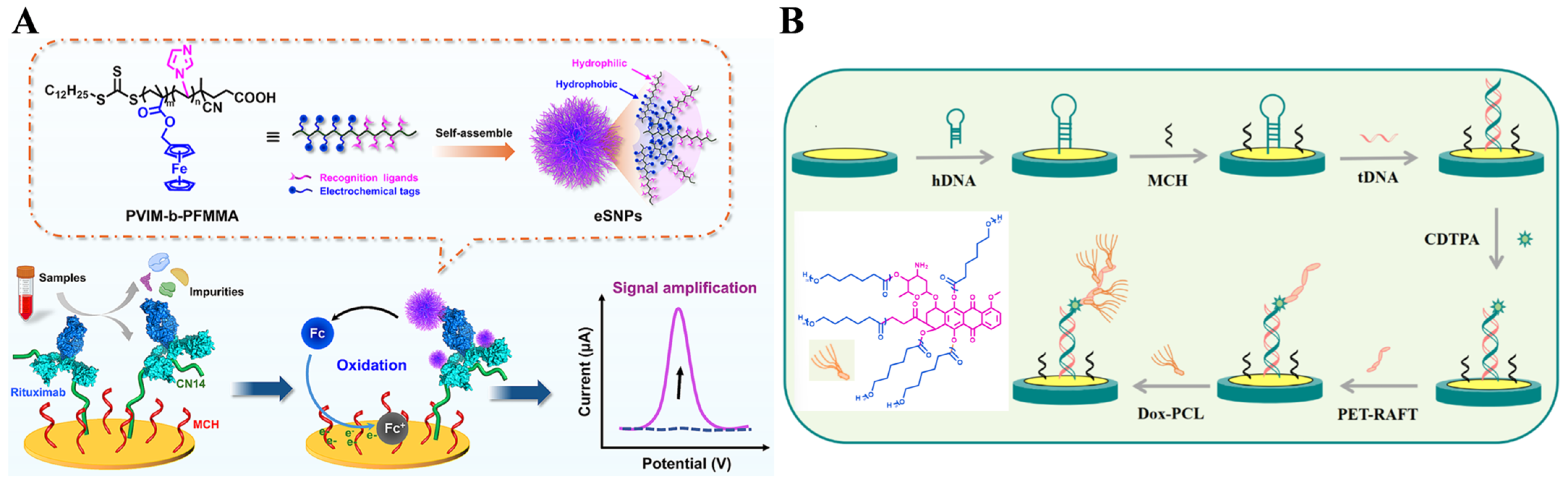

| Bioinspired eRAFT | DNA | 10−7–0.1 nM | 67 aM | [165] |

| trypsin | 25−175 μU/mL | 18.2 μU/mL | [166] | |

| PKA | 25−175 mU/mL | 1.85 mU/mL | [167] | |

| DNA | 10−4–10 pM | 4.39 aM | [168] | |

| DNA | 10−6–1 nM | 0.58 fM | [169] | |

| thrombin | 5×10−2–100 pM | 35.3 fM | [170] | |

| RitMab | 1–100 ng/mL | 0.14 ng/mL | [171] | |

| PET-RAFT | miRNA-21 | 10−5–100 pM | 4.48 aM | [173] |

| miRNA-21 | 10−4–100 pM | 12.4 aM | [174] |

5.1.5. Redox-Active Polymeric Materials for Signal Amplification

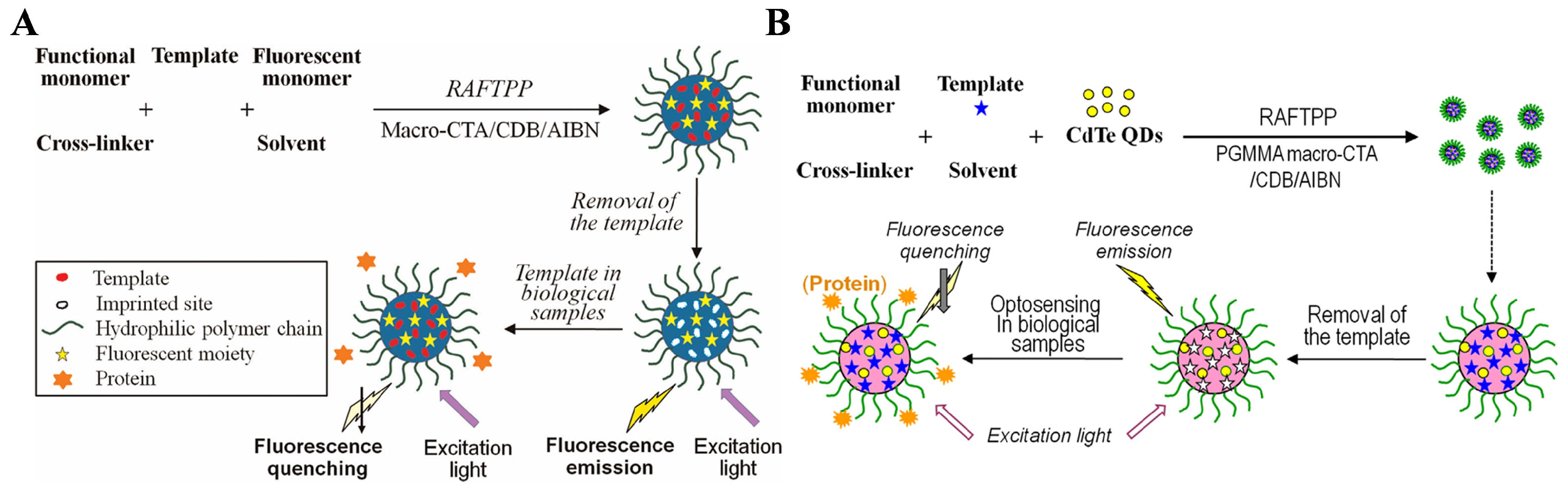

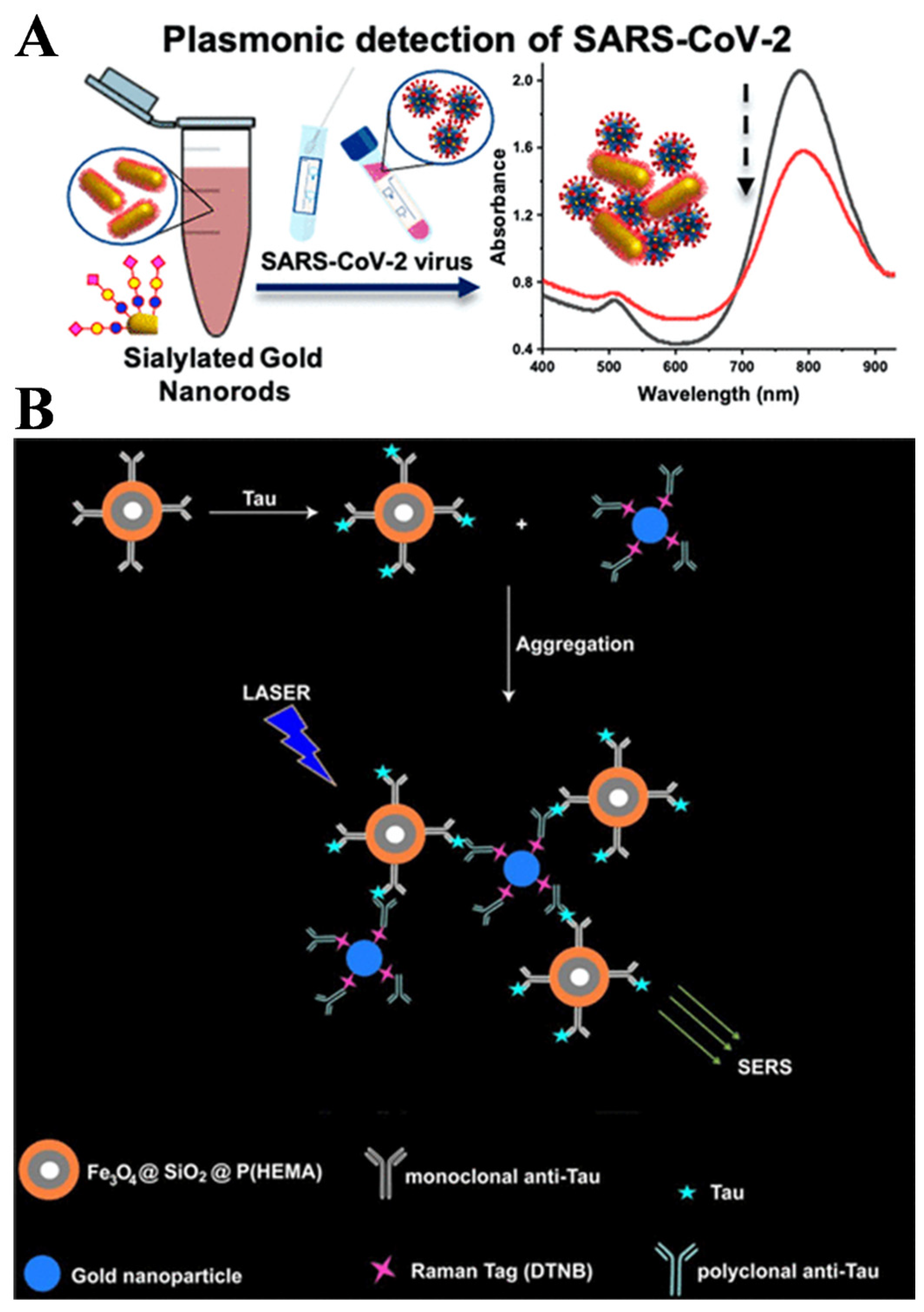

5.2. Optical Biosensors Based on RAFT Polymerization for Signal Amplification

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tovar-Lopez, F.J. Recent progress in micro- and nanotechnology-enabled sensors for biomedical and environmental challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiefari, J.; Chong, Y.; Ercole, F.; Krstina, J.; Jeffery, J.; Le, T.P.; Mayadunne, R.T.; Meijs, G.F.; Moad, C.L.; Moad, G. Living free-radical polymerization by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer: The RAFT process. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 5559–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothling, M.D.; Fu, Q.; Reyhani, A.; Allison-Logan, S.; Jung, K.; Zhu, J.; Kamigaito, M.; Boyer, C.; Qiao, G.G. Progress and perspectives beyond traditional RAFT polymerization. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, N.P.; Jones, G.R.; Bradford, K.G.E.; Konkolewicz, D.; Anastasaki, A. A comparison of RAFT and ATRP methods for controlled radical polymerization. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semsarilar, M.; Perrier, S. ‘Green’ reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, E.; Nabil, A.; Mochizuki, S.; Iijima, M.; Ebara, M. Preparation of temperature-responsive antibody–nanoparticles by RAFT-mediated grafting from polymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, L.; Rousset, C.; Monier, K.; Da Cruz-Boisson, F.; Bouvet, P.; Charreyre, M.-T.; Delair, T.; Fleury, E.; Favier, A. Fluorescent polymer-AS1411-aptamer probe for dSTORM super-resolution imaging of endogenous nucleolin. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 2302–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Chen, S.; Qu, X. One-pot preparation of ratiometric fluorescent molecularly imprinted polymer nanosensor for sensitive and selective detection of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Sensors 2024, 24, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H. Efficient optosensing of hippuric acid in the undiluted human urine with hydrophilic “turn-on”-type fluorescent hollow molecularly imprinted polymer microparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Boyer, C.; Kwon, M.S. Photocontrolled RAFT polymerization: Past, present, and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 3035–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keddie, D.J. A guide to the synthesis of block copolymers using reversible-addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, N.; Jung, K.; Moad, G.; Hawker, C.J.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Boyer, C. Reversible-deactivation radical polymerization (Controlled/living radical polymerization): From discovery to materials design and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 111, 101311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Cai, Y.; Fanslau, L.; Vana, P. Nanoengineering with RAFT polymers: From nanocomposite design to applications. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 6198–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Xin, F.; Qiao, R.; Davis, T.P. Engineering organic/inorganic nanohybrids through RAFT polymerization for biomedical applications. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 4243–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Li, C.; Chang, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, D.; Sun, J.; Liu, T.; Peng, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. Advances and prospects of RAFT polymerization-derived nanomaterials in MRI-assisted biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 146, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhara, M. Nanohybrid materials using gold nanoparticles and RAFT-synthesized polymers for biomedical applications. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2023, 60, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Song, M.; Hang, T.-J. Functional interfaces constructed by controlled/living radical polymerization for analytical chemistry. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 2881–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Gan, S.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, D.; Niu, L. Controlled/“living” radical polymerization-based signal amplification strategies for biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 3327–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.V.; Ek, J.I.; Ahn, E.C.; Sustaita, A.O. Molecularly imprinted polymers via reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer synthesis in sensing and environmental applications. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 9186–9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Feng, A.; Zhang, L.; Thang, S.H. Selection principle of RAFT chain transfer agents and universal RAFT chain transfer agents. Prog. Chem. 2022, 34, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Hakobyan, K.; Ishizuka, F.; Corrigan, N.; Xu, J.; Zetterlund, P.B.; Prescott, S.W.; Boyer, C. RAFT polymerization for advanced morphological control: From individual polymer chains to bulk materials. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2412407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Ren, N.; Zhu, X. Binary living radical polymerization of dual concurrent ATRP-RAFT. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lückerath, T.; Koynov, K.; Loescher, S.; Whitfield, C.J.; Nuhn, L.; Walther, A.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Ng, D.Y.W.; Weil, T. DNA–polymer nanostructures by RAFT polymerization and polymerization-induced self-assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15474–15479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Guisan, J.M.; Rocha-Martin, J. Oriented immobilization of antibodies onto sensing platforms—A critical review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1189, 338907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zheng, W.; Tucker, E.Z.; Gorman, C.B.; He, L. Reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization in DNA biosensing. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 3633–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fantin, M.; Park, S.; Gottlieb, E.; Fu, L.; Matyjaszewski, K. Electrochemically mediated reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 7872–7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q. Conjugated polymer based fluorescent probes for metal ions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 433, 213745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzen, M.; Elik, A.; Hazer, B.; Şimşek, S.; Altunay, N. Poly(styrene)-co-2-vinylpyridine copolymer as a novel solid-phase adsorbent for determination of manganese and zinc in foods and vegetables by FAAS. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Qiao, J.; Qi, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S. Synthesis of polymer protected AuNPs for silver ions detection. Sci. China Chem. 2015, 58, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xiao, L.; Marin, L.; Bai, Y.; Cheng, X. Fully-water-soluble BODIPY containing fluorescent polymers prepared by RAFT method for the detection of Fe3+ ions. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 150, 110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

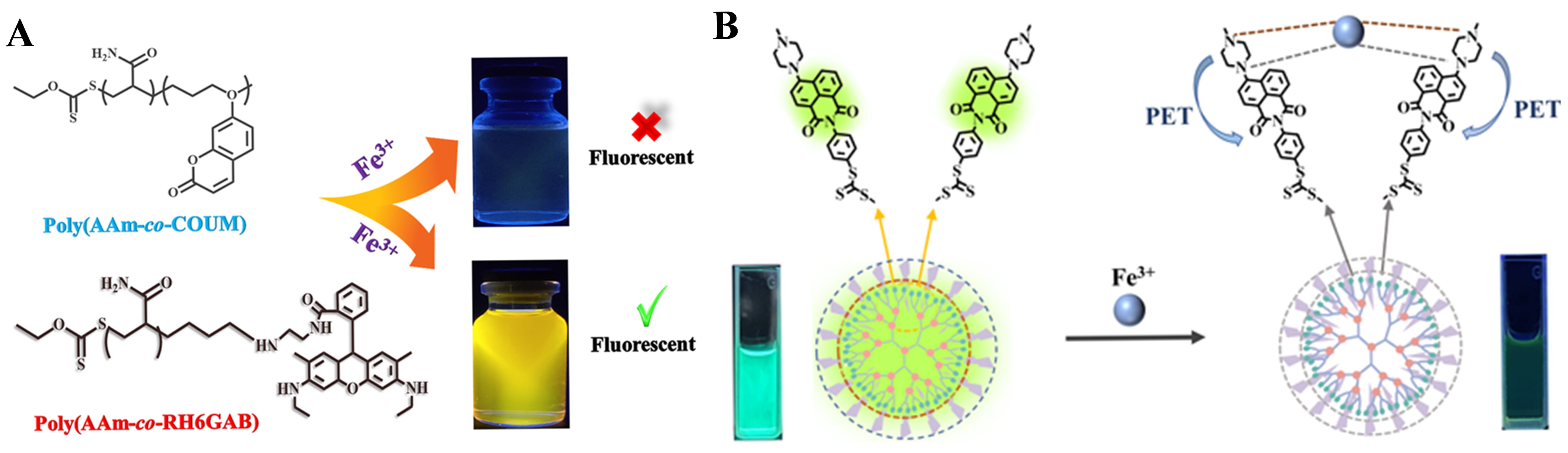

- Gheitarani, B.; Golshan, M.; Safavi-Mirmahalleh, S.-A.; Salami-Kalajahi, M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Alizadeh, A.A. Fluorescent polymeric sensors based on N-(rhodamine-G) lactam-N′-allyl-ethylenediamine and 7-(allyloxy)-2H-chromen-2-one for Fe3+ ion detection. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 656, 130473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Duan, L.; Cheng, G.; Cheng, X. Multi-functional RAFT reagent to prepare fluorescent hyper-branched macromolecular probes for the detection of Fe3+ ions. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 220, 113450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Lee, H.-I. Water-soluble polymeric probe with dual recognition sites for the sequential colorimetric detection of cyanide and Fe (III) ions. Dye. Pigment. 2019, 167, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sheng, Y.-J.; Sun, X.-L.; Wan, W.-M.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Q.; Chen, Q. Novel NBN-embedded polymers and their application as fluorescent probes in Fe3+ and Cr3+ detection. Polymers 2022, 14, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, X. Water soluble β-CD-PMAA/PMAm/PHEMA-Coumarin macromolecular fluorescent probes prepared via RAFT method and their sensing ability to Fe3+/Fe2+ and Cu2+ ions. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Chang, W.; Li, J. Pseudo-cryptand-containing copolymers: Cyclopolymerization and biocompatible water-soluble Al3+ fluorescent sensor in vitro. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; An, B.; Ni, L. Mixed polymeric micelles as a multifunctional visual thermosensor for the rapid analysis of mixed metal ions with Al3+ and Fe3+. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 12853–12864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, C.; Liu, S. Hg2+-reactive double hydrophilic block copolymer assemblies as novel multifunctional fluorescent probes with improved performance. Langmuir 2010, 26, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, U.; Lee, H.-I. BODIPY-derived multi-channel polymeric chemosensor with pH-tunable sensitivity: Selective colorimetric and fluorimetric detection of Hg2+ and HSO4− in aqueous media. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 4882–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegarzadeh, M.; Amini-Fazl, M.S.; Yazdi-Amirkhiz, S.Y. Polymethacrylamide-functionalized graphene oxide via the RAFT method: An efficient fluorescent nanosensor for heavy metals detection in aqueous media. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 4523–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, L.S.; Yuriychuk, N.; García, O.; López-González, M.; Quijada-Garrido, I. Exploring functional polymers in the synthesis of luminescent ZnO quantum dots for the detection of Cr6+, Fe2+, and Cu2+. Polymers 2024, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yin, C.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, X. Strategies for preparation of chitosan based water-soluble fluorescent probes to detect Cr3+ and Cu2+ ions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yun, L.; Cheng, X. Organic-soluble chitosan-g-PHMA (PEMA/PBMA)-bodipy fluorescent probes and film by RAFT method for selective detection of Hg2+/Hg+ ions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 237, 124255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, U.; Lee, H.-I. BODIPY-derived polymeric chemosensor appended with thiosemicarbazone units for the simultaneous detection and separation of Hg(II) ions in pure aqueous media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 13685–13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sheng, D.; Ma, Q. Quaternized salicylaldehyde Schiff base side-chain polymer-grafted magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the removal and detection of Cu2+ ions in water. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 611, 155632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, S. Responsive polymers-based dual fluorescent chemosensors for Zn2+ ions and temperatures working in purely aqueous media. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 2775–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; An, B.; Wang, Y.; Bao, X.; Ni, L.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Xie, X. A novel type of responsive double hydrophilic block copolymer-based multifunctional fluorescence chemosensor and its application in biological samples. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2017, 250, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, J.M.; Lee, H.-I. Use of core-cross-linked polymeric micelles induced by the selective detection of Cu(II) ions for the sustained release of a model drug. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 14368–14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschaert, N.; Caltagirone, C.; Rossom, W.V.; Gale, P.A. Applications of supramolecular anion recognition. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8038–8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, P.; Tian, H. Colorimetric naked-eye recognizable anion sensors synthesized via RAFT polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Pol. Chem. 2010, 48, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Jiang, J.; Leng, B.; Tian, H. Polymer fluoride sensors synthesized by RAFT polymerization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Bonder, E.M.; Jäkle, F. Electron-deficient triarylborane block copolymers: Synthesis by controlled free radical polymerization and application in the detection of fluoride ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17286–17289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Takahashi, E.; Ishizuki, A.; Nakabayashi, K. Tryptophan-containing block copolymers prepared by RAFT polymerization: Synthesis, self-assembly, and chiroptical and sensing properties. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 6451–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tao, F.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. A novel reversible colorimetric chemosensor for rapid naked-eye detection of Cu2+ in pure aqueous solution. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2015, 211, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Mei, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jing, T. Integrated ion imprinted polymers-paper composites for selective and sensitive detection of Cd(II) ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 333, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.J.; Davies, G.-L.; Gibson, M.I. Siderophore-inspired nanoparticle-based biosensor for the selective detection of Fe3+. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, J.M.; Gupta, M.; Jung, S.-H.; Lee, H.-I. Efficient colorimetric detection of cyanide ions using hemicyanine-based polymeric probes with detection-induced self-assembly in water. Polymer 2021, 213, 123320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, N.; Wang, J. Highly efficient selective extraction of chlorpyrifos residues from apples by magnetic microporous molecularly imprinted polymer prepared by reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer surface polymerization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.S.; Qiao, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Zhao, L.; Qi, L.; Moon, M.H. Online proteolysis and glycopeptide enrichment with thermoresponsive porous polymer membrane reactors for nanoflow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3124–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakanika, M.; Aleiferi, E.; Damalas, D.; Stergiou, A.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Sakellariou, G. Synthesis and molecular characterization of pyrene-containing copolymers as potential MALDI-TOF MS matrices. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 7500–7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydan, İ.; Bilici, M.; Turan, E.; Zengin, A. Selective extraction and determination of citrinin in rye samples by a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) using reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer precipitation polymerization (RAFTPP) with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) detection. Anal. Lett. 2021, 54, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubomirsky, E.; Preis, J.; Glassner, M.; Hofe, T.; Khodabandeh, A.; Hilder, E.F.; Arrua, R.D. Poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) monolith with dual porosity for size exclusion chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 19623–19631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhang, B.; Guo, P.; Chen, G.; Chang, C.; Fu, Q. Facile preparation of magnetic molecularly imprinted polymers for the selective extraction and determination of dexamethasone in skincare cosmetics using HPLC. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 41, 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.P.; Hilder, E.F.; Quirino, J.P.; Haddad, P.R. Electrokinetic chromatography and mass spectrometric detection using latex nanoparticles as a pseudostationary phase. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 4046–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Peuchen, E.H.; Dovichi, N.J. Surface-confined aqueous reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (SCARAFT) polymerization method for preparation of coated capillary leads to over 10 000 peptides identified from 25 ng HeLa digest by using capillary zone electrophoresis-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 6774–6780. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Schoenmakers, P.J.; van Dongen, J.L.J.; Lou, X.; Lima, V.; Brokken-Zijp, J. Mass spectrometric characterization of functional poly(methyl methacrylate) in combination with critical liquid chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 5517–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, M.; Turson, M.; Lin, S.; Jiang, P.; Dong, X. Preparation of clenbuterol imprinted monolithic polymer with hydrophilic outer layers by reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer radical polymerization and its application in the clenbuterol determination from human serum by on-line solid-phase extraction/HPLC analysis. Analyst 2013, 138, 3066–3074. [Google Scholar]

- Bilici, M.; Zengin, A. Facile synthesis of molecularly-imprinted magnetic-MoS2 nanosheets for selective and sensitive detection of ametryn. Chem. Phys. 2025, 589, 112526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Gong, B.; Ma, S.; Ou, J. Highly selective enrichment and direct determination of imazethapyr residues from milk using magnetic solid-phase extraction based on restricted-access molecularly imprinted polymers. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patinha, D.J.S.; Nellepalli, P.; Vijayakrishna, K.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Marrucho, I.M. Poly(ionic liquid) embedded particles as efficient solid phase microextraction phases of polar and aromatic analytes. Talanta 2019, 198, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Qiao, J.; Li, D.; Qi, L. Chiral ligand exchange capillary electrochromatography with dual ligands for enantioseparation of D,L-amino acids. Talanta 2019, 194, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xiao, R.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, X. Preparation and adsorption properties of molecularly imprinted polymer via RAFT precipitation polymerization for selective removal of aristolochic acid I. Talanta 2017, 162, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; You, H.; Xiong, H.; Chen, L. Water-compatible temperature and magnetic dual-responsive molecularly imprinted polymers for recognition and extraction of bisphenol A. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1435, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Lin, S.; Dong, X. Determination of tetracycline residues in lake water by on-line coupling of molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction with high performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 9446–9452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Zhou, W.-H.; Han, B.; Yang, H.-H.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.-R. Surface-imprinted core-shell nanoparticles for sorbent assays. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 5457–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, K.; Hu, Z.; et al. Biocompatible and antifouling linear poly(N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide)-coated capillaries via aqueous RAFT polymerization method for clinical proteomics analysis of non-small cell lung cancer tissue by CZE-ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 13974–13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Afgan, S.; Yadav, P.; Ganesan, V.; Kumar, R. Permselective films of sulfonic acid-functionalized N-vinylcarbazole block copolymers: Optoelectronic studies and electrochemical sensing of dopamine. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısır, M. Synthesis, characterization and sensor application of novel PCL-based triblock copolymers. Polymers 2025, 17, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajarathinam, T.; Thirumalai, D.; Jayaraman, S.; Yang, S.; Ishigami, A.; Yoon, J.-H.; Paik, H.-j.; Lee, J.; Chang, S.-C. Glutamate oxidase sheets-Prussian blue grafted amperometric biosensor for the real time monitoring of glutamate release from primary cortical neurons. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-W.; Cui, Z.-M.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Xu, F.; Chen, Y.-S.; Luo, Y.-L. Organic–inorganic nanohybrid electrochemical sensors from multi-walled carbon nanotubes decorated with zinc oxide nanoparticles and in-situ wrapped with poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl ferrocenecarboxylate) for detection of the content of food additives. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Li, A.; Liu, J. Simultaneous enhancement of bioactivity and stability of laccase by Cu2+/PAA/PPEGA matrix for efficient biosensing and recyclable decontamination of pyrocatechol. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2065–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajini, T.; Mathew, B. A brief overview of molecularly imprinted polymers: Highlighting computational design, nano and photo-responsive imprinting. Talanta Open 2021, 4, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. Synthesis of water-compatible surface-imprinted polymer via click chemistry and RAFT precipitation polymerization for highly selective and sensitive electrochemical assay of fenitrothion. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 62, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. Preparation of surface-imprinted polymer grafted with water-compatible external layer via RAFT precipitation polymerization for highly selective and sensitive electrochemical determination of brucine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 60, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, J.; Ye, H.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. Preparation of hydrophilic surface-imprinted ionic liquid polymer on multi-walled carbon nanotubes for the sensitive electrochemical determination of imidacloprid. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4704–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Highly sensitive Fe3O4 nanobeads/graphene-based molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor for 17β-estradiol in water. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 884, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X. Synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymer via visible light activated RAFT polymerization in aqueous media at room temperature for highly selective electrochemical assay of glucose. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2017, 218, 1700141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Rana, S.; Mehra, P.; Kaur, K. Surface-initiated reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization (SI-RAFT) to produce molecularly imprinted polymers on graphene oxide for electrochemical sensing of methylparathion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 49889–49901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Y.; Kang, J.; Qi, Q.; Zhong, C. Electrochemical sensors based on molecularly imprinted polymers on Fe3O4/graphene modified by gold nanoparticles for highly selective and sensitive detection of trace ractopamine in water. Analyst 2018, 143, 5094–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zheng, R.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; An, J.; Hao, C.; Kang, M. A novel surface molecularly imprinted polymer electrochemical sensor based on porous magnetic TiO2 for highly sensitive and selective detection of tetracycline. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 1614–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Kang, M.; Feng, H.; Hao, C.; Rong, X.; Zhao, H.; Ma, W.; Peng, W.; Li, Y. Molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor based on magnetic mesoporous nanocarriers for sensitive detection of tetrabromobisphenol A. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 11786–11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluz, Z.; Yazlak, M.G.; Kurşun, T.T.; Nayab, S.; Glasser, G.; Yameen, B.; Duran, H. Silica nanoparticles tailored with a molecularly imprinted copolymer layer as a highly selective biorecognition element. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, 2400471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislenko, E.; İncel, A.; Gawlitza, K.; Sellergren, B.; Rurack, K. Towards molecularly imprinted polymers that respond to and capture phosphorylated tyrosine epitopes using fluorescent bis-urea and bis-imidazolium receptors. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 10873–10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wu, F.; Huang, X.; He, S.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W. Fabrication of a molecularly-imprinted-polymer-based graphene oxide nanocomposite for electrochemical sensing of new psychoactive substances. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q. Ionic liquid-based thermally responsive electroactive gel for switchable electroanalysis. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 2462–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoum, A.; Altintas, Z.; Devi, K.S.S.; Forster, R.J. Electrochemiluminescence biosensors for detection of cancer biomarkers in biofluids: Principles, opportunities, and challenges. Nano Today 2023, 50, 101874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, F. Directionally in situ self-assembled iridium(III)-polyimine complex-encapsulated metal–organic framework two-dimensional nanosheet electrode to boost electrochemiluminescence sensing. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 12024–12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Xu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Li, A.; Liu, J. Simultaneous utilization of a bifunctional ruthenium complex as an efficient catalyst for RAFT controlled photopolymerization and a sensing probe for the facile fabrication of an ECL platform. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 5880–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chen, T.; Xu, Y.; Wei, S.; Huang, W.; Liu, R.; Liu, J. A versatile signal-enhanced ECL sensing platform based on molecular imprinting technique via PET-RAFT cross-linking polymerization using bifunctional ruthenium complex as both catalyst and sensing probes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 124–125, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Ding, J.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, F.; Zhuang, X.; Chen, Y. Recent advances in RAFT polymerization: Novel initiation mechanisms and optoelectronic applications. Polymers 2018, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, X. Easily water soluble cellulose-based fluorescent probes for the detection of 4-nitrophenol. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 40, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, C. Fluorescent PVP-g-chitosan polymer probes for the recognition of 4-nitrophenol. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 42, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Choudhury, N.; Bhadran, A.; Bauri, K.; De, P. Amino acid-derived alternating polyampholyte luminogens. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 3306–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Gu, P.; Wan, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, A.; Shi, H.; Xu, Q.; Lu, J. TPE-containing amphiphilic block copolymers: Synthesis and application in the detection of nitroaromatic pollutants. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 7244–7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Efficient one-pot synthesis of hydrophilic and fluorescent molecularly imprinted polymer nanoparticles for direct drug quantification in real biological samples. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Niu, H.; Zhang, H. One-pot synthesis of quantum dot-labeled hydrophilic molecularly imprinted polymer nanoparticles for direct optosensing of folic acid in real, undiluted biological samples. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balamurugan, A.; Lee, H.-I. A visible light responsive on–off polymeric photoswitch for the colorimetric detection of nerve agent mimics in solution and in the vapor phase. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 2568–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Lee, H.-I. A pyrene derived CO2-responsive polymeric probe for the turn-on fluorescent detection of nerve agent mimics with tunable sensitivity. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 6888–6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, J.; Cheng, X. Amphiphilic hyperbranched polymers for selective and sensitive detection of 4-nitrophenol. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 7590–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

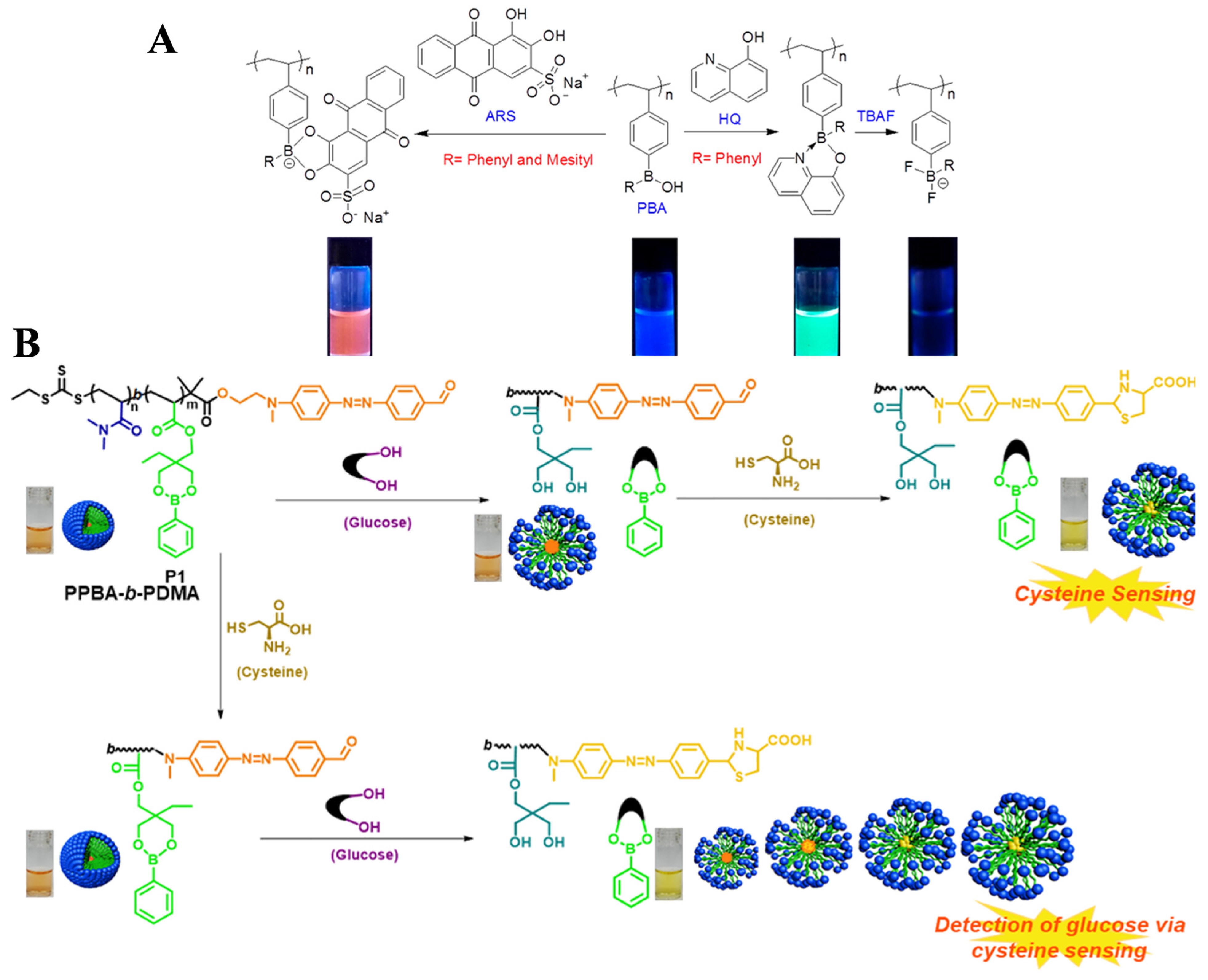

- Maji, S.; Vancoillie, G.; Voorhaar, L.; Zhang, Q.; Hoogenboom, R. RAFT polymerization of 4-vinylphenylboronic acid as the basis for micellar sugar sensors. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2014, 35, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, X.; Chang, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, W. Biosensors with boronic acid-based materials as the recognition elements and signal labels. Biosensors 2023, 13, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.-M.; Li, S.-S.; Liu, D.-M.; Lv, X.-H.; Sun, X.-L. Synthesis of electron-deficient borinic acid polymers with multiresponsive properties and their application in the fluorescence detection of Alizarin Red S and electron-rich 8-hydroxyquinoline and fluoride ion: Substituent effects. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 6872–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Haldar, U.; Lee, H.-I. Two-in-one dual-channel boronic ester block copolymer for the colorimetric detection of cysteine and glucose at neutral pH. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9915–9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Ahmad, R.; Kasthuri, S.; Pal, K.; Raviteja, S.; Nagaraaj, P.; Hoogenboom, R.; Nutalapati, V.; Maji, S. Pyrazoloanthrone-functionalized fluorescent copolymer for the detection and rapid analysis of nitroaromatics. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Duan, H.; Zhu, S.; Lü, J.; Lü, C. Preparation of a temperature-responsive block copolymer-anchored graphene oxide@ZnS NPs luminescent nanocomposite for selective detection of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 9598–9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.; Kobben, S.; Jiménez-Monroy, K.L.; Modesto, L.; Kraus, M.; Vandenryt, T.; Gaulke, A.; van Grinsven, B.; Ingebrandt, S.; Junkers, T.; et al. Thermal detection of histamine with a graphene oxide based molecularly imprinted polymer platform prepared by reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2014, 203, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Lü, J.; Liu, B.; Lü, C. Temperature responsive polymer brushes grafted from graphene oxide: An efficient fluorescent sensing platform for 2,4,6-trinitrophenol. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 7083–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlag, V.M.; Rodriguez, R.S.; Jung, S.; Bourgeois, M.R.; Bryson, S.; Purchel, A.; Schatz, G.C.; Haynes, C.L.; Reineke, T.M. Optimizing linear polymer affinity agent properties for surface-enhanced Raman scattering detection of aflatoxin B1. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2019, 4, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohalm, M.; Strohalm, J.; Kaftan, F.; Krásný, L.; Volný, M.; Novák, P.; Ulbrich, K.; Havlíček, V. Poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide]-based tissue-embedding medium compatible with MALDI mass spectrometry imaging experiments. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 5458–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbanks, B.D.; Gunatillake, P.A.; Meagher, L. Biomedical applications of polymers derived by reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT). Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 91, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherger, M.; Pilger, Y.A.; Stickdorn, J.; Komforth, P.; Schmitt, S.; Koynov, K.; Räder, H.J.; Nuhn, L. Efficient self-immolative RAFT end group modification for macromolecular immunodrug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2380–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Qin, Y.; Tan, T.; Lv, Y. Targeted live cell Raman imaging and visualization of cancer biomarkers with thermal-stimuli responsive imprinted nanoprobes. Part. Part. Syst. Char. 2018, 35, 1800390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lu, K.; Gu, C.; Heng, X.; Shan, F.; Chen, G. Synthetic sugar-only polymers with double-shoulder task: Bioactivity and imaging. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Niu, J.; Wei, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, X. Construction of dual-functional polymer nanomaterials with near-infrared fluorescence imaging and polymer prodrug by RAFT-mediated aqueous dispersion polymerization. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 10277–10287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Huang, Q.; Huang, L.; Huang, H.; Deng, F.; Wen, Y.; Tian, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. Facile preparation of fluorescent nanodiamond-based polymer composites through a metal-free photo-initiated RAFT process and their cellular imaging. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.J.; Wang, L. Synthesis of water-soluble europium-containing nanoprobes via polymerization-induced self-assembly and their cellular imaging applications. Talanta 2021, 232, 122182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkevicius, V.; Voronovic, E.; Jarockyte, G.; Skripka, A.; Vetrone, F.; Rotomskis, R.; Katelnikovas, A.; Karabanovas, V. Polymer brush coated upconverting nanoparticles with improved colloidal stability and cellular labeling. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, C.; Chen, X.; Tao, Y.; Wang, X. Multidentate comb-shaped polypeptides bearing trithiocarbonate functionality: Synthesis and application for water-soluble quantum dots. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.-H.; Oh, J.K. Research trends in the development of block copolymer-based biosensing platforms. Biosensors 2024, 14, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, Y.; Arslan, M.; Gevrek, T.N.; Sanyal, R.; Sanyal, A. Modular fabrication of polymer brush coated magnetic nanoparticles: Engineering the interface for targeted cellular imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 19813–19826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, X.; Tan, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Ming, D.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y. Hydrophilic polymer-brush functional fluorescent nanoparticles to suppress nonspecific interactions and enhance quantum yield for targeted cell imaging. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 2238–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Kundu, M.; Das, S.; Samanta, S.; Roy, S.S.; Mandal, M.; Singha, N.K. Glycopolymer decorated pH-dependent ratiometric fluorescent probe based on Förster resonance energy transfer for the detection of cancer cells. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, 2200594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Li, Y.; Lv, Y.; Ye, T.; Liu, X.; He, C.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z.; Shi, P. Fluorescent DNA-polymer enables signal amplification and precise protein localization in immunofluorescence imaging. Anal. Chem. 2025, 29, 15844–15854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Deng, X.; Liu, B.; Huang, S.; Ma, P.; Hou, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, J.; Luan, S. Construction of hierarchical polymer brushes on upconversion nanoparticles via NIR-light-initiated RAFT polymerization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 30414–30425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.F.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Chen, J.Y.; Lin, C.; Gao, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Cui, Z.K.; et al. Upper critical solution temperature polyvalent scaffolds aggregate and exterminate bacteria. Small 2022, 18, 2107374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Y.; Grazon, C.; Clavier, G.; Rieger, J.; Tian, Y.; Audibert, J.-F.; Sclavi, B.; Méallet-Renault, R. Fluorescent copolymers for bacterial bioimaging and viability detection. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2843–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, H.; Jin, Q.; Ji, J. IR-780 loaded phospholipid mimicking homopolymeric micelles for near-IR imaging and photothermal therapy of pancreatic cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 6852–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Chen, N.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D.; Yu, Y. Angiopep2-conjugated star-shaped polyprodrug amphiphiles for simultaneous glioma-targeting therapy and MR imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 12143–12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.W.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Ramasamy, B.; Goggi, J.; Chuang, K.-H.; He, T.; Robins, E.G. Octreotide functionalized nano-contrast agent for targeted magnetic resonance imaging. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 3902–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sanchez, R.J.P.; Fu, C.; Clayden-Zabik, R.; Peng, H.; Kempe, K.; Whittaker, A.K. Importance of thermally induced aggregation on 19F magnetic resonance imaging of perfluoropolyether-based comb-shaped poly(2-oxazoline)s. Biomacromolecules 2018, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Usman, A.; Zhang, Y.; Sawczyk, M.; Král, P.; Zhang, C.; Whittaker, A.K. Elucidating the impact of hydrophilic segments on 19F MRI sensitivity of fluorinated block copolymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, D.; Chang, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W. Photo-responsive self-assembled polymeric nanoparticle probes for 19F MRI theranostics. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W. Preparation of PFPE-based polymeric nanoparticles via polymerization-induced self-assembly as contrast agents for 19F MRI. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2918–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F. Portable electrochemical biosensor based on laser-induced graphene and MnO2 switch-bridged DNA signal amplification for sensitive detection of pesticide. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 199, 113906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altuntaş, D.B. Ultrasensitive analysis of BRCA-1 based on gold nanoparticles and molybdenum disulfide electrochemical immunosensor with enhanced signal amplification. Biosensors 2025, 15, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiddiky, M.J.A.; Kithva, P.H.; Kozak, D.; Trau, M. An electrochemical immunosensor to minimize the nonspecific adsorption and to improve sensitivity of protein assays in human serum. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 38, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyong, P.; Catli, C.; Davis, J.J. Ultrasensitive impedimetric immunosensor for the detection of C-reactive protein in blood at surface-initiated-reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer generated poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) brushes. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 4707–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Han, D.; Gan, S.; Bao, Y.; Niu, L. Surface-initiated-reversible-addition–fragmentation-chain-transfer polymerization for electrochemical DNA biosensing. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 12207–12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, K.; Kong, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Stable nitronyl nitroxide monoradical MATMP as novel monomer of reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization for ultrasensitive DNA detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1222, 340167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Kong, J. Ultrasensitive detection of CYFRA 21-1 DNA via SI-RAFT based in-situ metallization signal amplification. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Wen, D.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, D.; Kong, J. Electrochemical CYFRA21-1 DNA sensor with PCR-like sensitivity based on AgNPs and cascade polymerization. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 4155–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Sun, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. A dual signal amplification strategy combining thermally initiated SI-RAFT polymerization and DNA-templated silver nanoparticles for electrochemical determination of DNA. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Kong, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. Sensitive electrochemiluminescence analysis of lung cancer marker miRNA-21 based on RAFT signal amplification. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 1701–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Kong, J.; Han, D.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, L. Ultrasensitive peptide-based electrochemical detection of protein kinase activity amplified by RAFT polymerization. Talanta 2020, 206, 120173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Sulfur-free reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer emulsion polymerization strategy for electrochemical analysis of protein kinase A activity. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 9859–9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Bao, Y.; Gan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Han, D.; Niu, L. Amplified electrochemical biosensing of thrombin activity by RAFT polymerization. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 3470–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Li, L.; Qi, X.; An, B.; Ma, K.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. A Multi-Site initiation reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer electrochemical cocaine sensing. Microchem. J. 2022, 181, 107714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yang, H.; Kong, J. Ultrasensitive electrochemical immunosensor via RAFT polymerization signal amplification for the detection of lung cancer biomarker. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 882, 114971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, M.A. An electrochemical PNA-based sensor for the detection of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRP by using surface-initiated-reversible-addition fragmentation-chain-transfer polymerization technique. Talanta 2023, 259, 124490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Miao, M. Enhanced electrochemical aptasensor integrating MoS2/CuS-Au and SI-RAFT for dual signal amplification in cTnI detection. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 163, 108862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Kong, J.; Han, D.; Niu, L.; Zhang, X. Electrochemical DNA biosensing via electrochemically controlled reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Kong, J.; Han, D.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Niu, L. Electrochemically controlled RAFT polymerization for highly sensitive electrochemical biosensing of protein kinase activity. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 1936–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Su, L.; Mao, Y.; Gan, S.; Bao, Y.; Qin, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, L. Electrochemically induced grafting of ferrocenyl polymers for ultrasensitive cleavage-based interrogation of matrix metalloproteinase activity. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 178, 113010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, W.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Ultrasensitive detection of DNA via SI-eRAFT and in situ metalization dual-signal amplification. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 9198–9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Su, L.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cao, X.; Luo, Y.; Qin, D.; Niu, L. Coenzyme-mediated electro-grafting for ultrasensitive electrochemical DNA biosensing. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2021, 346, 130551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Su, L.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qin, D.; Niu, L. Coenzyme-mediated electro-RAFT polymerization for amplified electrochemical interrogation of trypsin activity. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 9602–9608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Su, L.; Luo, Y.; Cao, X.; Hu, S.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, W.; Qin, D.; et al. Biologically mediated RAFT polymerization for electrochemical sensing of kinase activity. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 6200–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Li, L.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Coenzyme-catalyzed electroinitiated reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer polymerization for ultrasensitive electrochemical DNA detection. Talanta 2022, 236, 122840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Cao, X.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Niu, L. Bioinspired electro-RAFT polymerization for electrochemical sensing of nucleic acids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 54794–54800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wan, J.; Hu, Q.; Qin, D.; Han, D.; Niu, L. Target-synergized biologically mediated RAFT polymerization for electrochemical aptasensing of femtomolar thrombin. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 4570–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Wu, D.; Hu, Q.; Niu, L. Biologically-driven RAFT polymerization-amplified platform for electrochemical detection of antibody drugs. Talanta 2025, 285, 127431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, N.; Liu, L. Boronic acid-based approach for separation and immobilization of glycoproteins and its application in sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 20890–20912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, J.; Kong, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Ultrasensitive miRNA-21 biosensor based on Zn(TCPP) PET-RAFT polymerization signal amplification and multiple logic gate molecular recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 17716–17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wei, G.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, J.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Organic small molecule catalytic PET-RAFT electrochemical signal amplification strategy for miRNA-21 detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 152380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.A.; Yager, P.; Hoffman, A.S.; Stayton, P.S. Mixed stimuli-responsive magnetic and gold nanoparticle system for rapid purification, enrichment, and detection of biomarkers. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 2197–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, W.; Bai, L. Synthesis of PGMA/AuNPs amplification platform for the facile detection of tumor markers. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 183, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfar, S.; Ghanbari, R.; Attaripour Isfahani, A.; Rezaei, H.; Kheirollahi, M. A novel signal amplification tag to develop rapid and sensitive aptamer-based biosensors. Bioelectrochemistry 2022, 145, 108087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liao, Y.; Qu, J.-H.; Gan, N.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Electroactive supramolecular nanoprobes for electrochemical detection of rituximab in non-Hodgkon’s lymphoma patients. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 157875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, H.; Guo, L.; Gao, W.; Cheng, D.; Liu, Y. A novel label-free impedance biosensor for KRAS G12C mutations detection based on PET-RAFT and ROP synergistic signal amplification. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 161, 108844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, F.A.; Alipour, E.; Mohammadi, R.; Amini-Fazl, M.S.; Abnous, K. Development of novel aptasensor for ultra-sensitive detection of myoglobin via electrochemical signal amplification of methylene blue using poly (styrene)-block-poly (acrylic acid) amphiphilic copolymer. Talanta 2022, 237, 122950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonschii, C.; Potara, M.; Iancu, M.; David, S.; Banciu, R.M.; Vasilescu, A.; Astilean, S. Progress in the optical sensing of cardiac biomarkers. Biosensors 2023, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevrek, T.N.; Degirmenci, A.; Sanyal, R.; Klok, H.-A.; Sanyal, A. Succinimidyl carbonate-based amine-reactive polymer brushes: Facile fabrication of functional interfaces. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 2507–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukum, K.O.; Caykara, T.; Demirel, G. Thermoresponsive polymer brush-decorated 3-D plasmonic gold nanorod arrays as an effective plasmonic aensing platform. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 4296–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.L.; Battrell, C.F.; Pennell, S.; Hoffman, A.S.; Lai, J.J.; Stayton, P.S. Simple fluidic system for purifying and concentrating diagnostic biomarkers using stimuli-responsive antibody conjugates and membranes. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, N.; Kurioka, H.; Komura, C.; Ajiro, H.; Ando, T. Synthesis of a novel carboxybetaine copolymer with different spacer lengths and inhibition of nonspecific protein adsorption on its polymer film. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 2330–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancaro, A.; Szymonik, M.; Georgiou, P.G.; Baker, A.N.; Walker, M.; Adriaensens, P.; Hendrix, J.; Gibson, M.I.; Nelissen, I. The polymeric glyco-linker controls the signal outputs for plasmonic gold nanorod biosensors due to biocorona formation. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 10837–10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, P.G.; Guy, C.S.; Hasan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Richards, S.-J.; Baker, A.N.; Thakkar, N.V.; Walker, M.; Pandey, S.; Anderson, N.R.; et al. Plasmonic detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with polymer-stabilized glycosylated gold nanorods. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zengin, A.; Tamer, U.; Caykara, T. A SERS-based sandwich assay for ultrasensitive and selective detection of Alzheimer’s tau protein. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3001–3009. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, T.; Ahmad, M.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Wei, T. A recyclable tetracycline imprinted polymeric SPR sensor: In synergy with itaconic acid and methacrylic acid. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 3102–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

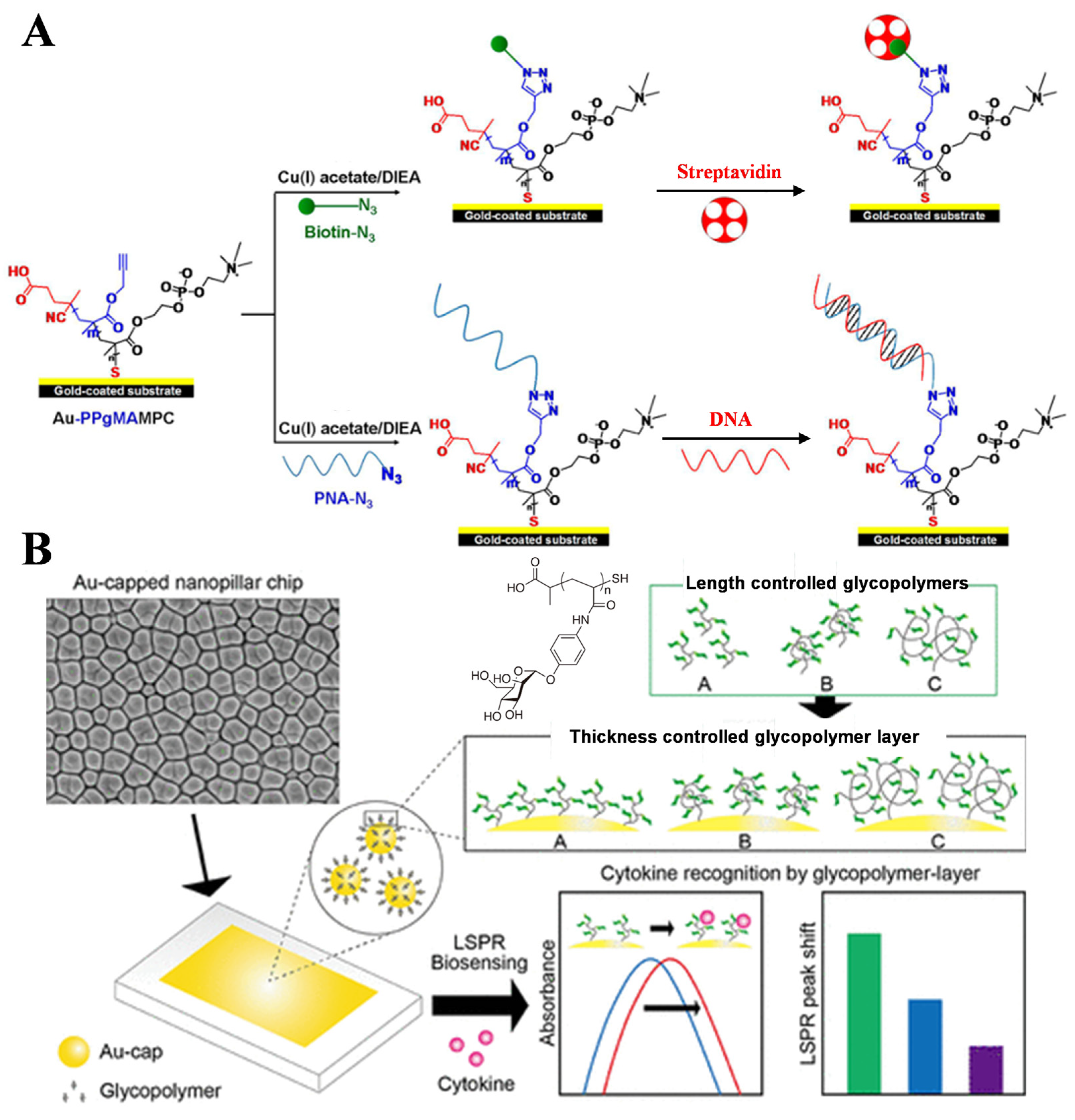

- Wiarachai, O.; Vilaivan, T.; Iwasaki, Y.; Hoven, V.P. Clickable and antifouling platform of poly[(propargyl methacrylate)-ran-(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine)] for biosensing applications. Langmuir 2016, 32, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, Y.; Obara, A.; Takamatsu, H.; Espulgar, W.V.; Saito, M.; Tamiya, E. Au-capped nanopillar immobilized with a length-controlled glycopolymer for immune-related protein detection. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 7913–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Wong, K.H.; Granville, A.M. Enhancement of localized surface plasmon resonance polymer based biosensor chips using well-defined glycopolymers for lectin detection. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 462, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Huang, H.; Xu, D.; Crommen, J.; et al. Inside-out oriented choline phosphate-based biomimetic masgnetic nanomaterials for precise recognition and analysis of C-reactive protein. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 3532–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Shi, J.; Yang, Y. Recent development of surface-enhanced Raman scattering for biosensing. J. Nanobiotech. 2023, 21, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

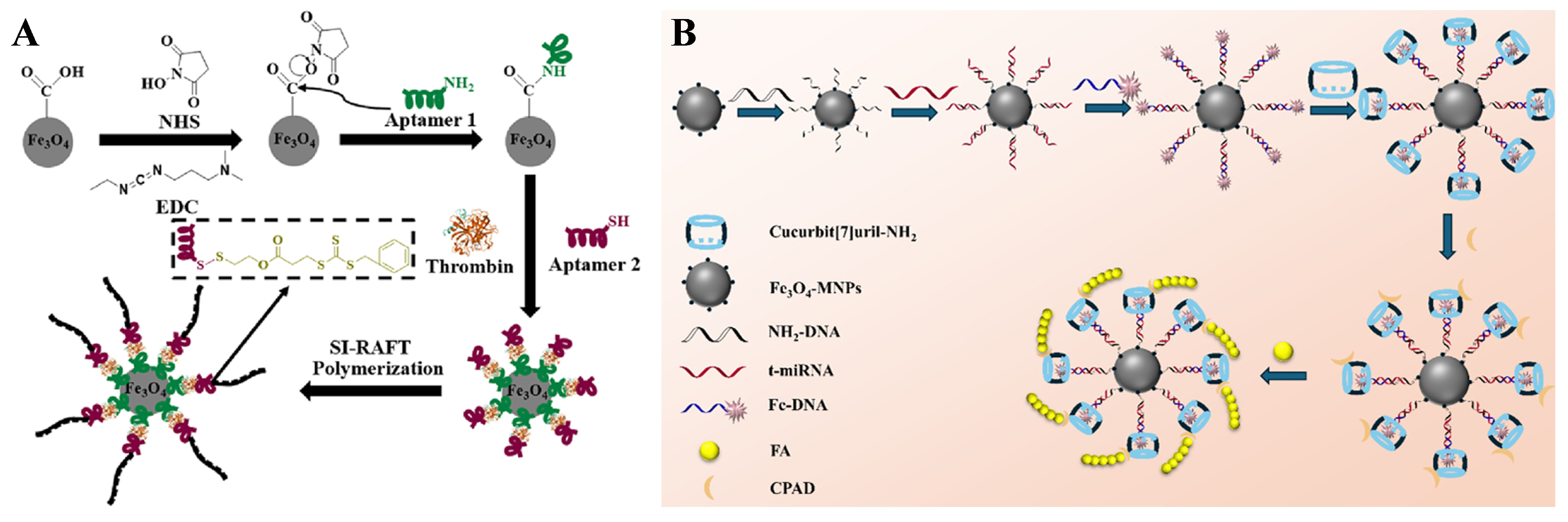

- Liu, Z.; Ma, N.; Yu, S.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Hemin-catalyzed SI-RAFT polymerization for thrombin detection. Microchem. J. 2023, 189, 108521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Ma, N.; Kong, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, X. Molybdate-driven and cucurbit[7]uril-assembled ultrasensitive miRNA fluorescence sensor. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2026, 344, 126654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

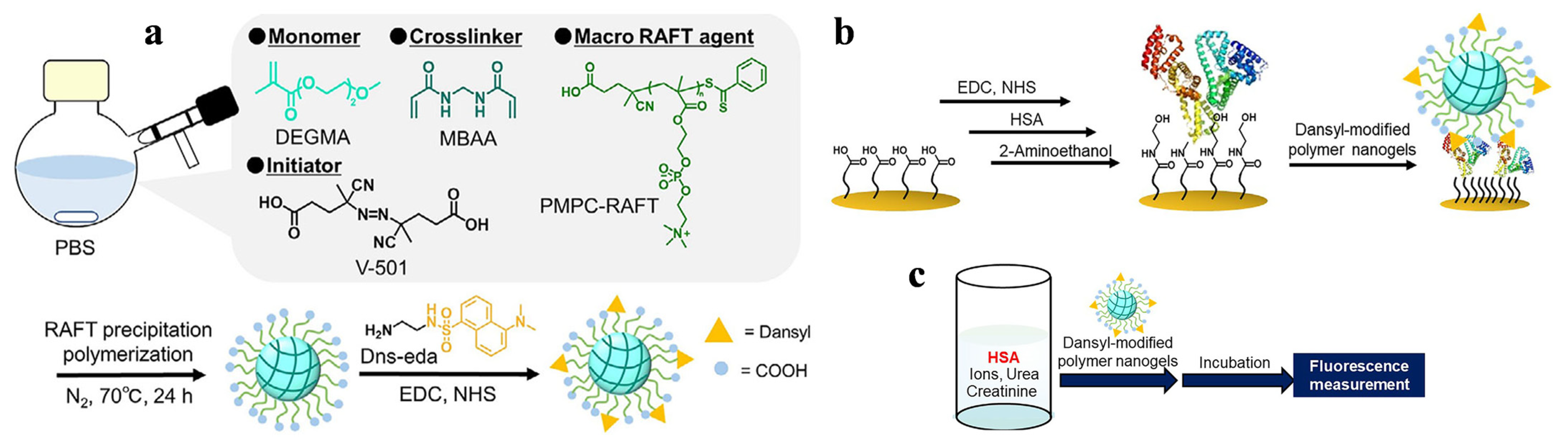

- Kitayama, Y.; Yoshimatsu, E.; Harada, A. Polymer nanogels with albumin reporting interface created using RAFT precipitation polymerization for disease diagnosis and food testing. Adv. Mater. Interf. 2025, 12, 2500147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Consideration | RAFT | ATRP |

|---|---|---|

| How does reversible deactivation occur? | Degenerate transfer: Pn• + CTA–Pm ⇌ CTA–Pn + Pm• | Atom transfer: Pn–X + activator ⇌ Pn• + deactivator |

| How are radicals generated? | Initiator2 → 2Initiator• | R–X + LCuIX ⇌ R• + LCuIIX2 |

| Macroradical concentration [Pn•] | Similar [Pn•] to conventional steady-state radical polymerization. Termination is not curbed; chain transfer competes with both termination and propagation | Low [Pn•] due to activation–deactivation equilibrium. Low rate of termination |

| Theoretical degree of polymerization (DP) | DPRAFT = [Monomer]/[CTA] | DPATRP = [Monomer]/[R–X] |

| Obtaining narrow molecular weight distributions | As well as sufficient deactivation, CTA must be consumed early in the reaction: rct > rpropagation | As well as sufficient deactivation, R–X must be consumed early in the reaction: rinitiation > rpropagation |

| Ensuring predictable molecular weights | CTA must be fully consumed for theoretical and experimental molecular weights to agree | R–X must be fully consumed for theoretical and experimental molecular weights to agree |

| Maximizing end- group fidelity | The number of dead chains in conventional RAFT is determined by the number of initiators that have decomposed. Using low [Initiator2] gives higher end-group fidelity | End-group fidelity is enhanced by selecting a catalyst that favors deactivation over activation, lowering [Pn•] and rtermination |

| Ease of implementation | Simpler to implement, it uses fewer components (monomer, radical initiator, and CTA). The activity of the monomer must be matched with the CTA. Reactions are similar to conventional radical polymerization with added CTA | More components: monomer, ATRP initiator, activator, deactivator, and ligand. The activity of the monomer has to be matched with the activity of the initiator and ligand |

| Reaching high monomer conversions | Radical generation continues until all radical initiators are consumed. If 100% conversion is achieved but the initiator is still present, then further termination can occur | Radical generation continues to occur even at 100% conversion, potentially impacting end-group fidelity |

| pH tolerance | Typically not tolerant to basic environments due to degradation of CTAs at high pH | Few examples under acidic conditions due to protonation of N-donor ligands at low pH |

| Practical downsides | Polymers are often yellow or pink in color. CTAs often have a bad odor, and polymers can require purification to avoid this | Polymers are often blue/green to brown in color. Residual metal species may be problematic for some applications |

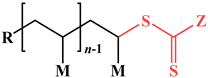

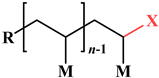

| End group |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Z.-J.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.-L.; Yu, S.-B. Overview on the Sensing Materials and Methods Based on Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization. Biosensors 2025, 15, 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15100673

Yu Z-J, Liu L, Yang S-L, Yu S-B. Overview on the Sensing Materials and Methods Based on Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization. Biosensors. 2025; 15(10):673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15100673

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Zhao-Jiang, Lin Liu, Su-Ling Yang, and Shuai-Bing Yu. 2025. "Overview on the Sensing Materials and Methods Based on Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization" Biosensors 15, no. 10: 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15100673

APA StyleYu, Z.-J., Liu, L., Yang, S.-L., & Yu, S.-B. (2025). Overview on the Sensing Materials and Methods Based on Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization. Biosensors, 15(10), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15100673