Phase Transitions and Switching Dynamics of Topological Domains in Hafnium Oxide-Based Cylindrical Ferroelectrics from Three-Dimensional Phase Field Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

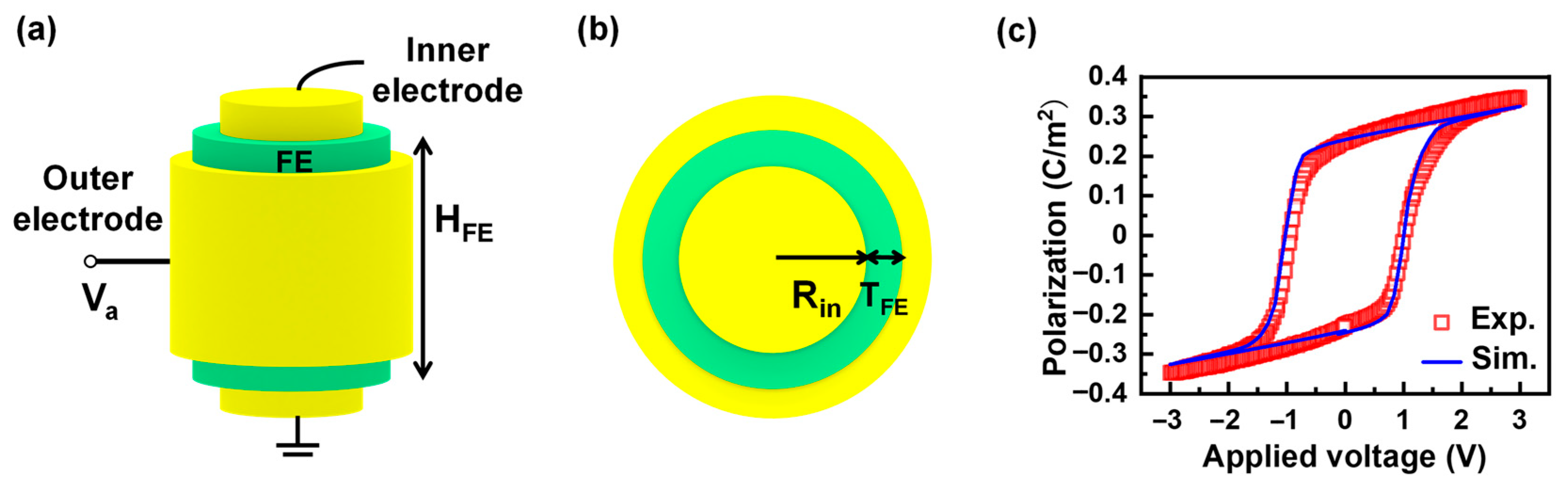

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

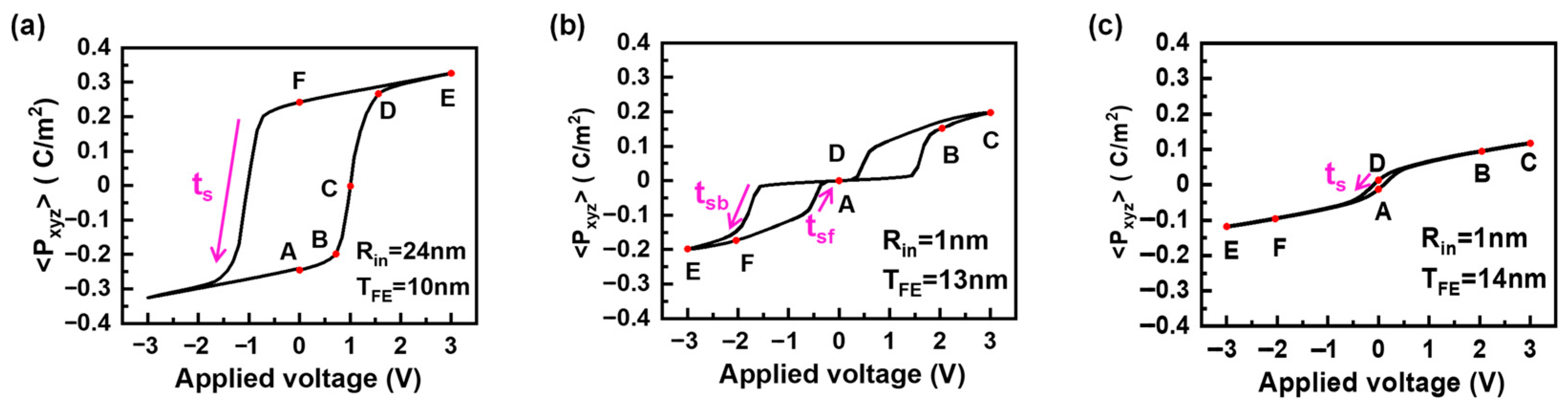

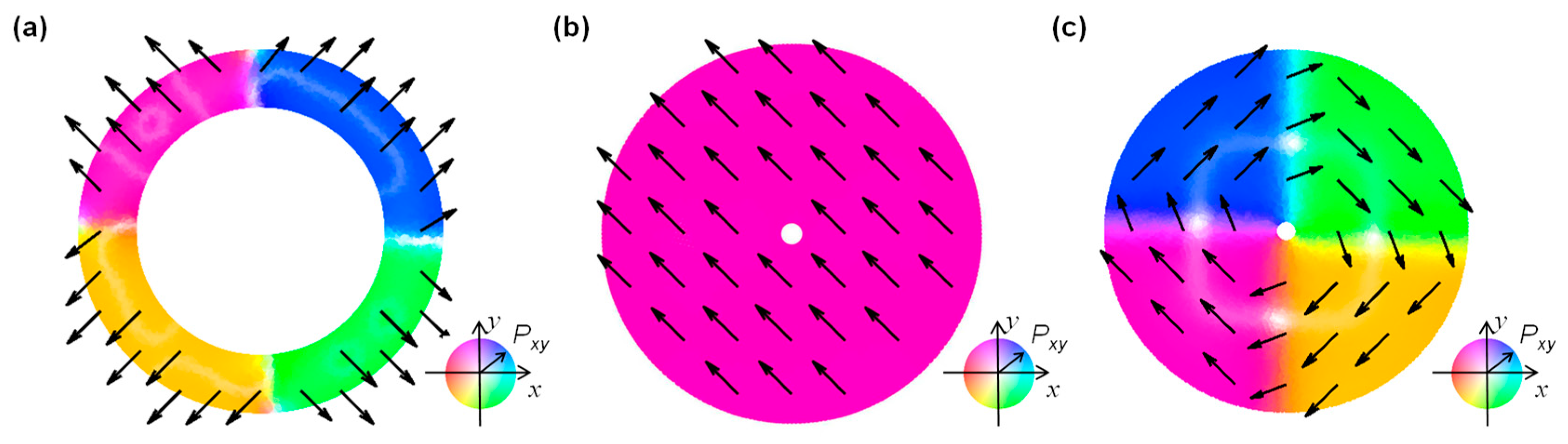

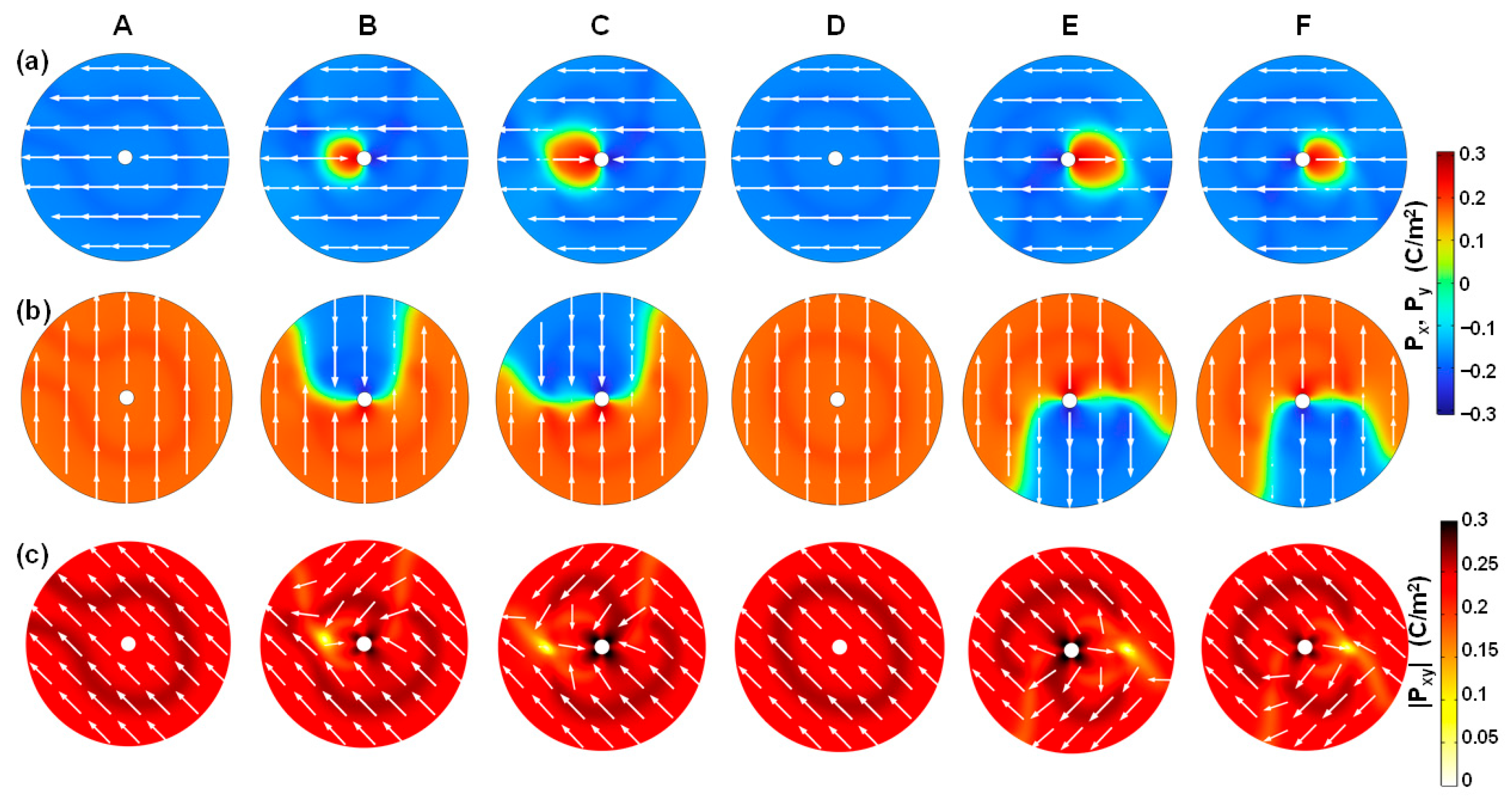

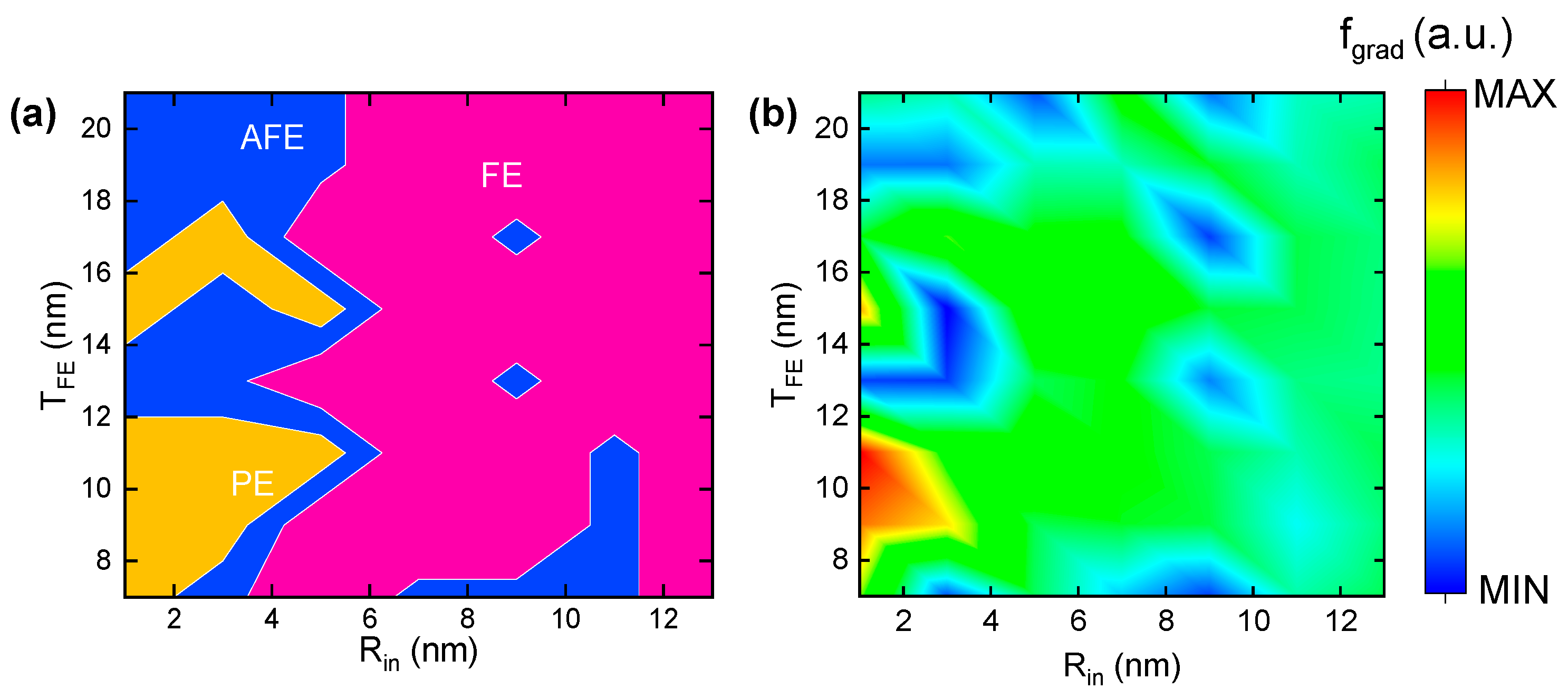

3.1. Phase Transitions Along with Topological Domain Patterns

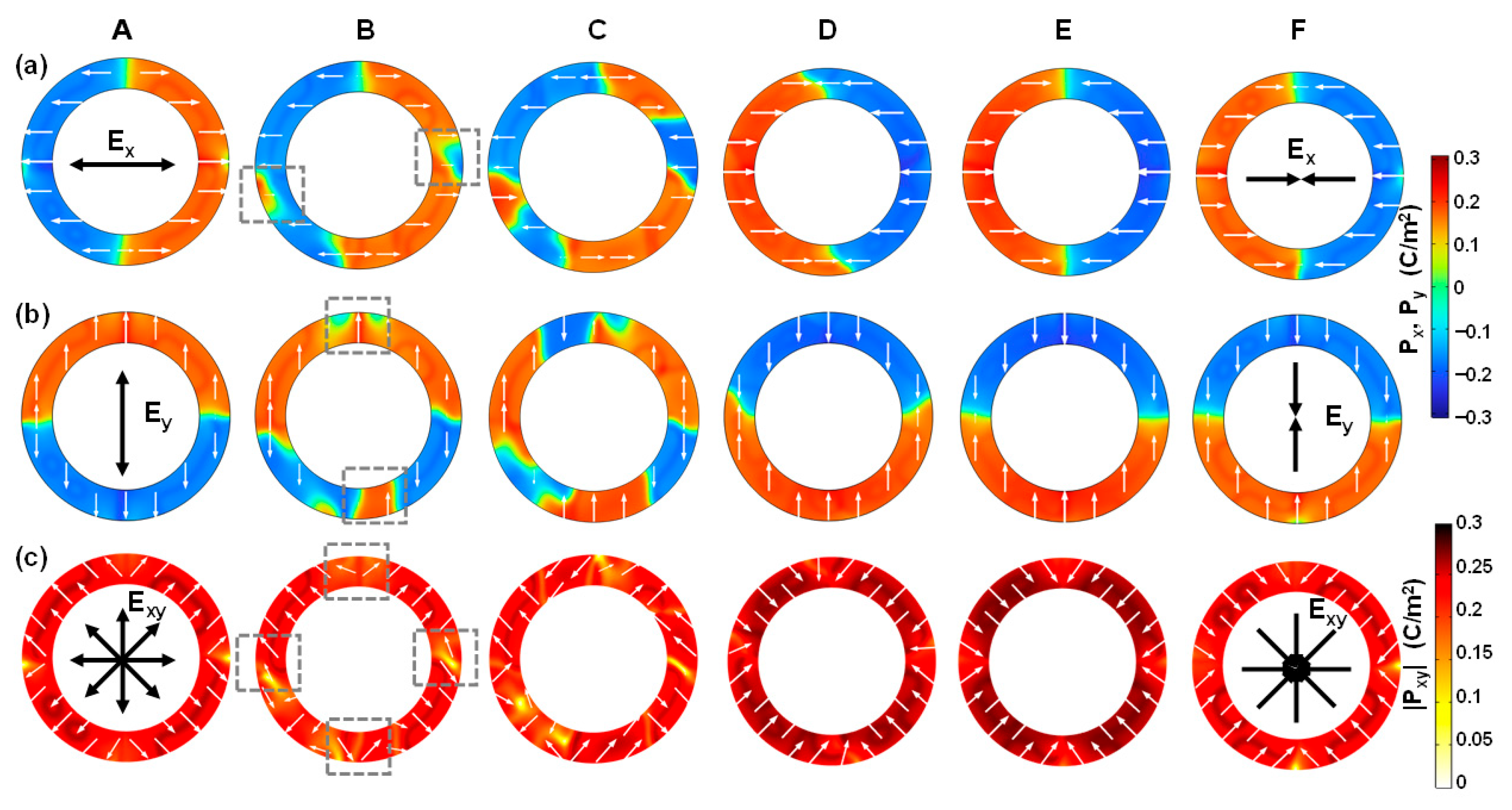

3.2. Switching Dynamics of Ferroelectric Phase

3.3. Switching Dynamics of Antiferroelectric Phase

3.4. Switching Dynamics of Paraelectric Phase

3.5. Energy Competition in Different Phases

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Hong, A.J.; Kim, S.M.; Shin, K.S.; Song, E.B.; Hwang, Y.; Xiu, F.; Galatsis, K.; Chui, C.O.; Candler, R.N. A stacked memory device on logic 3D technology for ultra-high-density data storage. Nanotechnology 2011, 2, 254006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Gao, B.; Yu, S.; Zhao, L.; Chen, B.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hou, T.H.; Nishi, Y. Design and optimization methodology for 3D RRAM arrays. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 9–11 December 2013; pp. 25.7.1–25.7.4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Jin, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, G. Ferroelectric-like behaviors of metal-insulator-metal with amorphous dielectrics. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2013, 66, 200410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Yang, T.; Shi, D.; Zhou, W.; Huo, Z. Optimization of Performance and Reliability in 3D NAND Flash Memory. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2020, 41, 840–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, I.G.; Park, C.J.; Ju, H.; Seong, D.J.; Ahn, H.S.; Kim, J.H. Realization of vertical resistive memory (VRRAM) using cost effective 3D process. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Electron Devices Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 December 2011; pp. 31.8.1–31.8.4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Hong, A.J.; Ogawa, M.; Ma, S.; Song, E.B.; Lin, Y.S. Novel 3-D structure for ultra high density flash memory with VRAT (Vertical-Recess-Array-Transistor) and PIPE (Planarized Integration on the same Plan E). In Proceedings of the 2008 Symposium on VLSI Technology, Honolulu, HI, USA, 17–19 June 2008; pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, S.; Takenaka, M.; Toprasertpong, K. Prospects and challenges of HfO2-based ferroelectric devices. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68, 160407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhong, N.; Cheng, Y.; Xin, T.; Luo, Q.; Gong, T.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Cheng, R.; Fu, Z.; et al. Ferroelectric materials, devices, and chips technologies for advanced computing and memory applications: Development and challenges. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68, 160401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, G.; Huo, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, G.; Wu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, H. Recent progress of hafnium oxide-based ferroelectric devices for advanced circuit applications. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2023, 66, 200405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, J.; Kunihiro, T.; Konishi, K.; Materano, M.; Ali, T.; Kuehnel, K. 1T1C FeRAM Memory Array Based on Ferroelectric HZO With Capacitor Under Bitline. IEEE J. Electron. Devices Soc. 2022, 10, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.K.; Kim, J.S.; Zhu, Z.; Choi, Y.S.; Yoon, A.; MacDonald, M.R.; Lei, X.; Lee, T.Y.; Lee, D. Engineering of ferroelectric switching speed in Si doped HfO2 for high-speed 1T-FERAM application. In Proceedings of the International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–6 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Kim, T.; Myeong, I.; Park, S.; Noh, S.; Lee, S.M.; Woo, J.; Ko, H.; Noh, Y.; Choi, M.; et al. Comprehensive Design Guidelines of Gate Stack for QLC and Highly Reliable Ferroelectric VNAND. In Proceedings of the International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–6 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Florent, K.; Pesic, M.; Subirats, A.; Banerjee, K.; Lavizzari, S.; Arreghini, A.; Di Piazza, L.; Potoms, G.; Sebaai, F.; McMitchell, S.R.C.; et al. Vertical Ferroelectric HfO2 FET based on 3-D NAND Architecture: Towards Dense Low-Power Memory. In Proceedings of the International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 1–5 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema, S.S.; Kwon, D.; Shanker, N.; dos Reis, R.; Hsu, S.-L.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wagner, R.; Datar, A.; McCarter, M.R.; et al. Enhanced ferroelectricity in ultrathin films grown directly on silicon. Nature 2020, 580, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.; Du, G.; Kang, J.; Liu, X. Conduction mechanisms of metal-ferroelectric-insulator-semiconductor tunnel junction on N- and P-type semiconductor. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2021, 42, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, K.-Y.; Liao, C.-Y.; Liu, J.-H.; Wang, J.-F.; Chiang, S.-H.; Chang, S.-H.; Hsieh, F.-C.; Liang, H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lou, Z.-F.; et al. Bilayer-Based Antiferroelectric HfZrO2 Tunneling Junction With High Tunneling Electroresistance and Multilevel Nonvolatile Memory. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2021, 42, 1464–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.Y.; Hsiang, K.Y.; Lou, Z.F.; Tseng, H.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Hsieh, F.C.; Wang, C.C.; Chang, F.S. Endurance > 1011 Cycling of 3D GAA Nanosheet Ferroelectric FET with Stacked HfZrO2 to Homogenize Corner Field Toward Mitigate Dead Zone for High-Density eNVM. In Proceedings of the Symposium on VLSI Technology, Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, M.; Su, C.; Fu, Z.; Wang, K.; Huang, R.; Huang, Q. New Understanding of Screen Radius and Re-evaluation of Memory Window in Cylindrical Ferroelectric Capacitor for High-density 1T1C FeRAM. In Proceedings of the IEEE Electron Devices Technology & Manufacturing Conference (EDTM), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 28 February–3 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.-C.; Hur, J.; Yu, S. Ferroelectric Tunnel Junction Based Crossbar Array Design for Neuro-Inspired Computing. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2021, 20, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Birol, T. Triggered ferroelectricity in HfO2 from hybrid phonons. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.08633. [Google Scholar]

- Delodovici, F.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Trilinear-coupling-driven ferroelectricity in HfO2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 064405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Nelson, C.T.; Hsu, S.L.; Hong, Z.; Clarkson, J.D. Observation of polar vortices in oxide superlattices. Nature 2016, 530, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Tang, Y.L.; Hong, Z.; Gonçalves, M.A.P.; McCarter, M.R.; Klewe, C.; Nguyen, K.X.; Gómez-Ortiz, F.; Shafer, P.; Arenholz, E.; et al. Observation of room-temperature polar skyrmions. Nature 2019, 568, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xie, L.; Liu, G.; Prokhorenko, S.; Nahas, Y.; Pan, X.; Bellaiche, L. Nanoscale bubble domains and topological transitions in ultrathin ferroelectric films. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Feng, Y.P.; Zhu, Y.L.; Tang, Y.L.; Yang, L.X. Polar meron lattice in strained oxide ferroelectrics. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tian, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, F.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Fan, Z.; Hou, Z. Quasi-one-dimensional metallic conduction channels in exotic ferroelectric topological defects. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tian, G.; Fan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Hou, Z.; Chen, D. Nonvolatile ferroelectric-domain-wall memory embedded in a complex topological domain structure. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2107711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tian, G.; Li, P.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, F.; Yao, J.; Fan, H.; Song, X.; Chen, D.; et al. High-density array of ferroelectric nanodots with robust and reversibly switchable topological domain states. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Bai, Z.L.; Chen, Z.H.; He, L.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhang, Q.H.; Shi, J.A.; Park, M.H. Temporary formation of highly conducting domain walls for non-destructive read-out of ferroelectric domain-wall resistance switching memories. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sando, D.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, X.; Prosandeev, S.; Bulanadi, R. Conformational domain wall switch. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Yang, W.; Song, X.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Li, P.; Fan, H.; Yao, J.; Chen, D. Manipulation of conductive domain walls in confined ferroelectric nanoislands. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Cao, R.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, R.; Wei, W.; Zheng, Y.; Gong, T.; et al. A highly CMOS compatible hafnia-based ferroelectric diode. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.; Guo, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Zeng, L. Topological Polarization Dynamics and Domain-Wall Tunneling Electroresistance Effects in Cylindrical-Shell Ferroelectrics. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2024, 46, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Chang, P.; Du, G.; Kang, J.; Liu, X. Impacts of Radius on the Characteristics of Cylindrical Ferroelectric Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2020, 67, 5810–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Nonaka, A.; Jambunathan, R.; Pahwa, G.; Salahuddin, S.; Yao, Z. FerroX: A GPU-accelerated, 3D phase-field simulation framework for modeling ferroelectric devices. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2023, 290, 108757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, H.; Hong, J.; Wang, X. Strain manipulation of ferroelectric skyrmion bubbles in a freestanding PbTiO3 film: A phase field simulation. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 224101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, E.A.; Morozovska, A.N.; Nelson, C.T.; Kalinin, S.V. Intrinsic structural instabilities of domain walls driven by gradient coupling: Meandering antiferrodistortive-ferroelectric domain walls in BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 014112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Huang, H.; Hu, F.; Wang, J.T.; Chen, C.F. Merons in strained PbZr0.2Ti0.8O3 thin films: Insights from phase-field simulations. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 094116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Du, G.; Liu, X. Design space for stabilized negative capacitance in HfO2 ferroelectric-dielectric stacks based on phase field simulation. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2021, 64, 122402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Roh, J.; Lee, Y.B.; Hwang, C.S. Modeling of negative capacitance in ferroelectric thin films. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1805266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.Y.; Mizoguchi, T. Electric Field-Induced Phase Transitions and Hysteresis in Ferroelectric HfO2 Captured with Machine Learning Potential. npj Quantum Mater. 2024, 9, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Du, G.; Liu, X. Experiment and modeling of dynamical hysteresis in thin film ferroelectrics. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 59, SGGA07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Böscke, T.S.; Schröder, U.; Mueller, S.; Bräuhaus, D.; Böttger, U.; Frey, L.; Mikolajick, T. Ferroelectricity in Simple Binary ZrO2 and HfO2. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 4318–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.; Adelmann, C.; Singh, A.; Van Elshocht, S.; Schroeder, U.; Mikolajick, T. Ferroelectricity in Gd-Doped HfO2 Thin Films. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2012, 1, N123–N126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Schröder, U.; Böscke, T.S.; Müller, I.; Böttger, U.; Wilde, L.; Sundqvist, J.; Lemberger, M.; Kücher, P.; Mikolajick, T.; et al. Ferroelectricity in yttrium-doped hafnium oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 114113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešić, M.; Fengler, F.P.G.; Larcher, L.; Padovani, A.; Schenk, T.; Grimley, E.D.; Sang, X.; LeBeau, J.M.; Slesazeck, S.; Schroeder, U.; et al. Physical mechanisms behind the field-cycling behavior of HfO2-based ferroelectric capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 4601–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozovska, A.N.; Strikha, M.V.; Kelley, K.P.; Kalinin, S.V.; Eliseev, E.A. Effective Landau-type model of a HfxZr1−xO2-graphene nanostructure. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 20, 054007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kamlah, M.; Zhang, T.Y. Phase field simulations of ferroelectric nanoparticles with different long-range-electrostatic and -elastic interactions. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 014104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| α1 | −2.5 × 109 | V·m/C |

| α11 | −2 × 108 | V·m5/C3 |

| α12 | 5 × 108 | V·m5/C3 |

| α111 | 3.2 × 1011 | V·m9/C5 |

| α112 | 3.5 × 1011 | V·m9/C5 |

| α123 | 3.5 × 1011 | V·m9/C5 |

| G11 | 1 × 10−9 | V·m3/C |

| G12 | 0 | V·m3/C |

| G44 | 1 × 10−9 | V·m3/C |

| G′44 | 1 × 10−9 | V·m3/C |

| C11 | 450.129 | GPa |

| C12 | 124.003 | GPa |

| C44 | 5.469 | GPa |

| Q11 | 0.0056 | m4/C2 |

| Q12 | −0.0059 | m4/C2 |

| Q44 | 0.0385 | m4/C2 |

| Γ | 0.01 | S/m |

| εFE | 30 | 1 |

| f | 10 | kHz |

| HFE | 10 | nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, P.; Zhang, H.; Xie, M.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Y. Phase Transitions and Switching Dynamics of Topological Domains in Hafnium Oxide-Based Cylindrical Ferroelectrics from Three-Dimensional Phase Field Simulation. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241901

Chang P, Zhang H, Xie M, Zhang H, Xie Y. Phase Transitions and Switching Dynamics of Topological Domains in Hafnium Oxide-Based Cylindrical Ferroelectrics from Three-Dimensional Phase Field Simulation. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241901

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Pengying, Hanxiao Zhang, Mengyao Xie, Huan Zhang, and Yiyang Xie. 2025. "Phase Transitions and Switching Dynamics of Topological Domains in Hafnium Oxide-Based Cylindrical Ferroelectrics from Three-Dimensional Phase Field Simulation" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241901

APA StyleChang, P., Zhang, H., Xie, M., Zhang, H., & Xie, Y. (2025). Phase Transitions and Switching Dynamics of Topological Domains in Hafnium Oxide-Based Cylindrical Ferroelectrics from Three-Dimensional Phase Field Simulation. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241901