A Dual-Scale Encapsulation Strategy for Phase Change Materials: GTS-PEG for Efficient Heat Storage and Release

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of SiO2 Aerogel

2.3. Preparation of GTS

2.4. Preparation of GTS-PEG Composite PCMs

2.5. Characterization

3. Discussion and Results

3.1. Optimized Preparation of SiO2 Aerogel

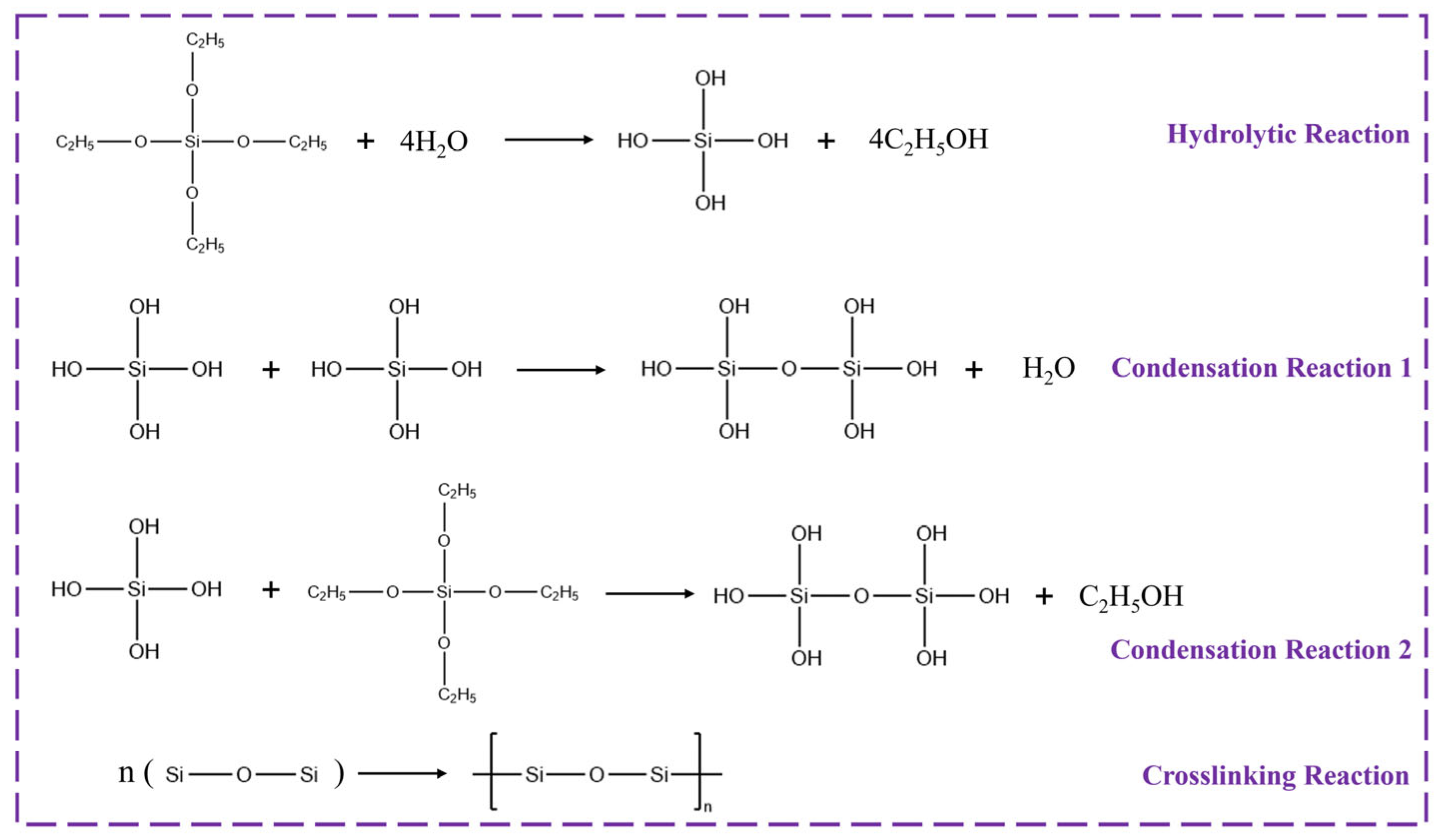

3.2. Relevant Mechanisms of Action

3.3. Microstructural Characterization

3.4. Macroscopic Characterization

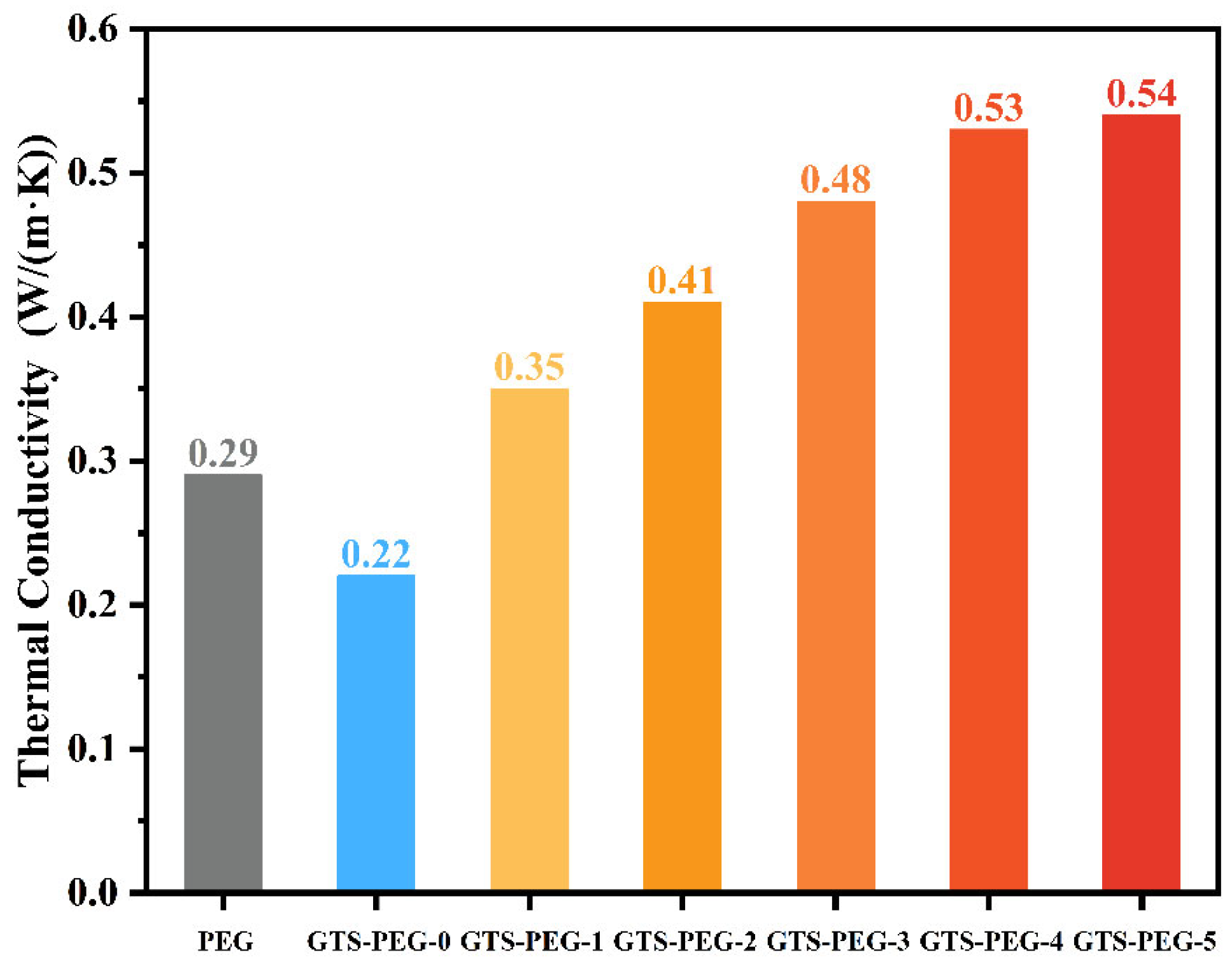

3.5. Thermal Conductive Properties of GTS-PEG

3.6. The Surface Structure of the GTS Framework

3.7. Crystal Structure of the GTS Framework

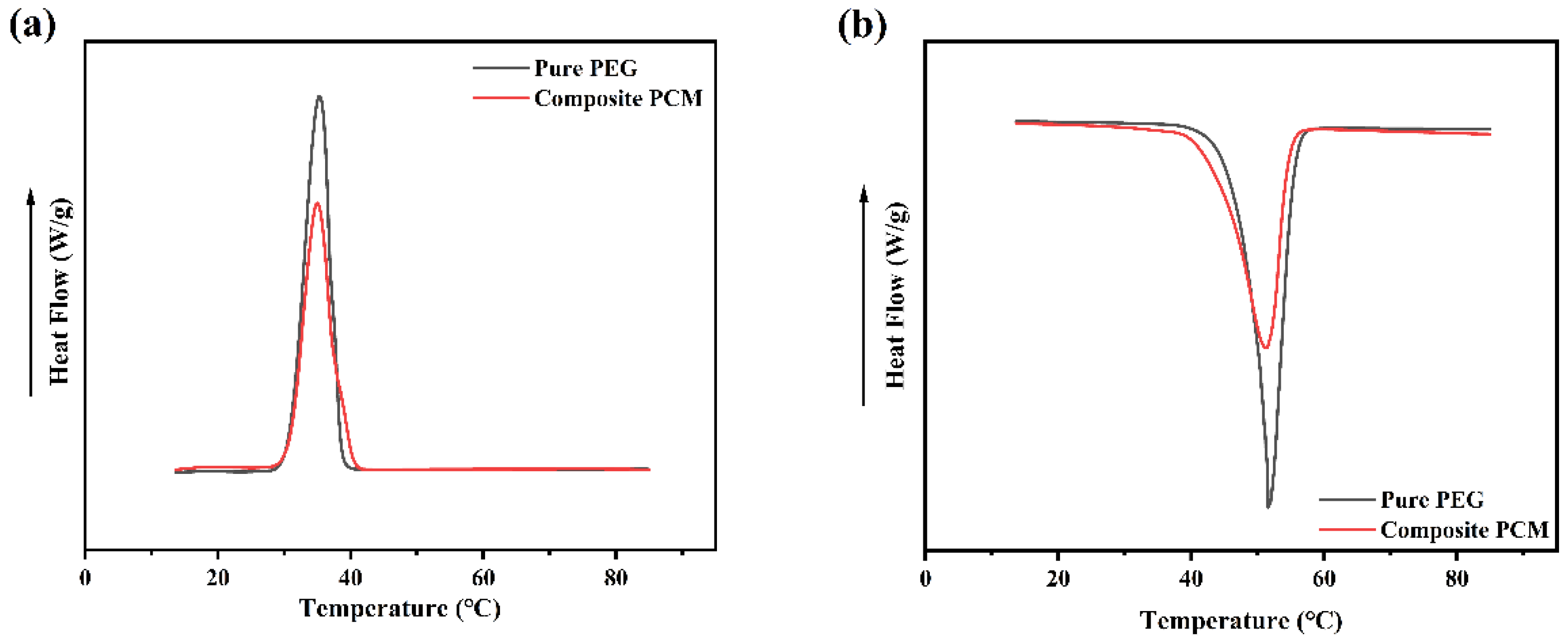

3.8. Analysis of GTS-PEG Heat Storage and Release Properties

3.9. Temperature–Time Variation During Cooling Processes of GTS-PEG

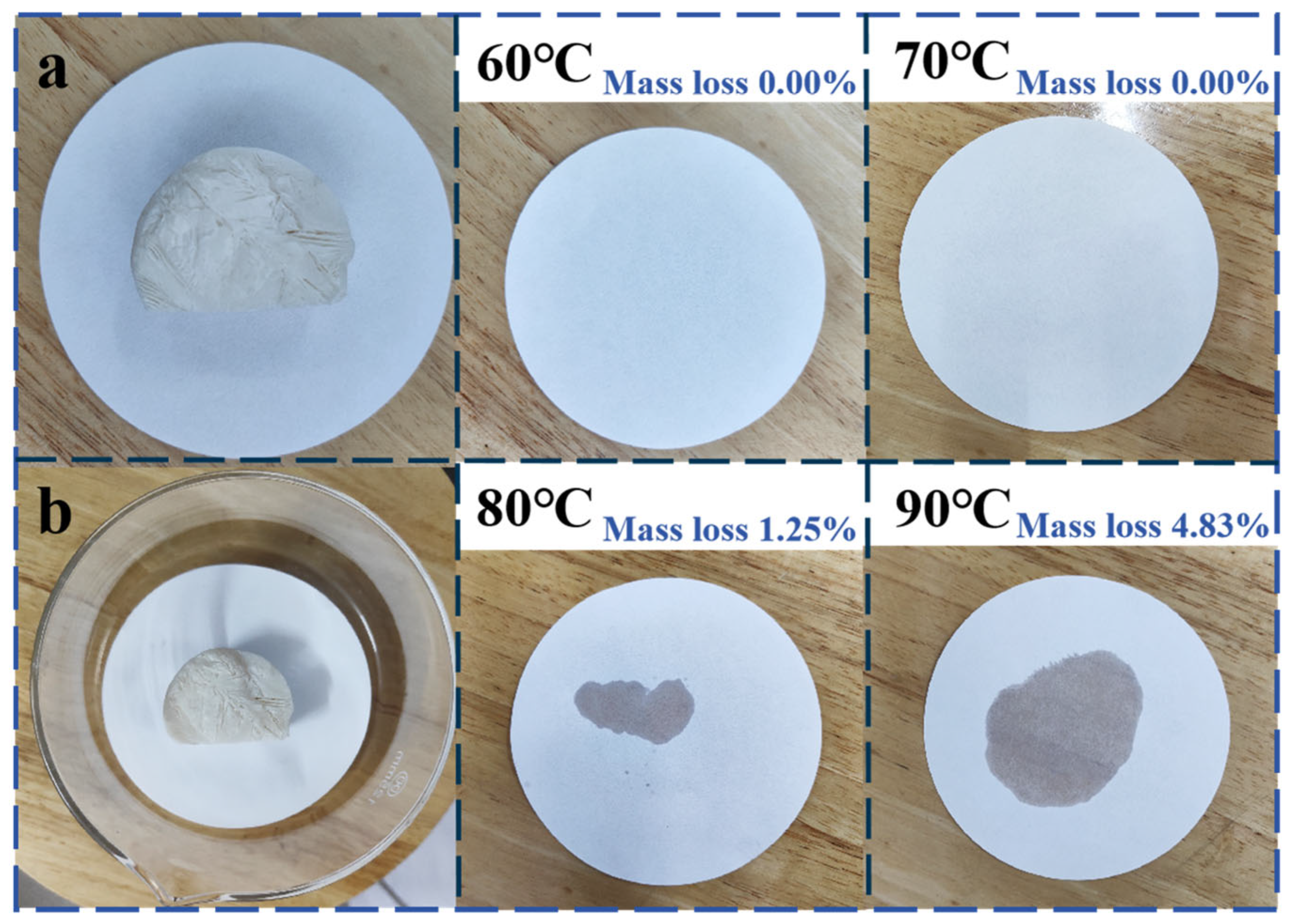

3.10. The Leakage-Proof Performance of GTS-PEG

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xi, L.; Shi, Y.; Quan, Y.; Liu, Z. Research on the multi-area cooperative control method for novel power systems. Energy 2024, 313, 133912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Ge, W. Mobileception-ResNet for transient stability prediction of novel power systems. Energy 2024, 309, 133163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ochieng, W.; Pien, K.-C.; Shang, W.-L. Carbon-efficient timetable optimization for urban railway systems considering wind power consumption. Appl. Energy 2025, 388, 125593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Geng, H.; Mu, G. Modeling of wind turbine generators for power system stability studies: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yang, H.; Li, Y. Design and simulation of a silicon carbide power module with double-sided cooling and no wire bonding. Electr. Mater. Appl. 2024, 1, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, Y. Optimal configuration of shared energy storage for multi-microgrid systems: Integrating battery decommissioning value and renewable energy economic consumption. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 343, 120156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Most, L.; van der Wiel, K.; Benders, R.M.J.; Gerbens-Leenes, P.W.; Bintanja, R. Temporally compounding energy droughts in European electricity systems with hydropower. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Deane, P.; Ó Gallachóir, B.; Pfenninger, S.; Staffell, I. Impacts of Inter-annual Wind and Solar Variations on the European Power System. Joule 2018, 2, 2076–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Trakas, D.N.; Mancarella, P.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Power Systems Resilience Assessment: Hardening and Smart Operational Enhancement Strategies. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, N.A.; Jenkins, J.D.; Edington, A.; Mallapragada, D.S.; Lester, R.K. The design space for long-duration energy storage in decarbonized power systems. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.A.; Rinaldi, K.Z.; Ruggles, T.H.; Davis, S.J.; Yuan, M.; Tong, F.; Lewis, N.S.; Caldeira, K. Role of Long-Duration Energy Storage in Variable Renewable Electricity Systems. Joule 2020, 4, 1907–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, F.; Cañizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Anierobi, C.; Calero, I.; Souza, M.F.Z.d.; Farrokhabadi, M.; Guzman, N.S.; Mendieta, W.; Peralta, D.; et al. A Review of Modeling and Applications of Energy Storage Systems in Power Grids. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 806–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yan, T.; Kuai, Z.; Pan, W. Thermal conductivity enhancement on phase change materials for thermal energy storage: A review. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 25, 251–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.G. Energy Storage and Power Electronics Technologies: A Strong Combination to Empower the Transformation to the Smart Grid. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 2191–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M. Research progress on carbon aerogel composite phase-change energy storage materials. Carbon 2025, 244, 120725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Li, A.; Chen, X. Phase Change Thermal Storage Materials for Interdisciplinary Applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6953–7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boning, R. Review on thermal properties and reaction kinetics of Ca(OH)2/CaO thermochemical energy storage materials. Electr. Mater. Appl. 2024, 1, e12007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, B. The promise of phase-change materials. Science 2019, 366, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Long-Term Infrared Stealth by Sandwich-Like Phase-Change Composites at Elevated Temperatures via Synergistic Emissivity and Thermal Regulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, S.; Fu, H.; Qu, J.; Zhang, Z. Yin-Yang heat flow rate converter: Based on Guar Gum composite phase change materials with controllable thermal conductivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lei, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zou, D. Metal-based phase change material (PCM) microcapsules/nanocapsules: Fabrication, thermophysical characterization and application. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 438, 135559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, K.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Qing, C.; Zou, D. Development and applications of multifunctional microencapsulated PCMs: A comprehensive review. Nano Energy 2024, 122, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikutegbe, C.A.; Al-Shannaq, R.; Farid, M.M. Microencapsulation of low melting phase change materials for cold storage applications. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Qin, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, C. Multi-layer graphene nanosheets bridging binary aluminium oxide for the synergistic enhancement of thermal conductivity and electrical insulation of silicone resin composite. Electr. Mater. Appl. 2024, 1, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, G. The marriage of two-dimensional materials and phase change materials for energy storage, conversion and applications. EnergyChem 2022, 4, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-R.; Hu, N.; Fan, L.-W. Nanocomposite phase change materials for high-performance thermal energy storage: A critical review. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 55, 727–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Biomimetic phase change materials for extreme thermal management. Matter 2022, 5, 2495–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.; Zhang, Z.; Rumi, S.S.; Abidi, N. Enhanced guar gum aerogel formation assisted by cottonseed protein isolate. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi, H.; Fathi, Z.; Abidnejad, R.; Silva, P.E.S.; Bordoloi, S.; Vapaavuori, J.; Niskanen, J.; Lizundia, E.; Kontturi, E.; Lipponen, J. Biochar-infused cellulose foams with PEG-based phase change materials for enhanced thermal energy storage and photothermal performance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 367, 123999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Hu, D.; Cai, Z.; Yin, X.; Dong, L.; Huang, L.; Xiong, C.; Jiang, M. Latent heat and thermal conductivity enhancements in polyethylene glycol/polyethylene glycol-grafted graphene oxide composites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2019, 2, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Gao, S.; Diao, Z.; Li, J.; Shao, M.; Song, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, F.; et al. Phenolic Modified SiO2 Aerogel as a Hybrid Thermal Insulation Systems. Langmuir 2025, 41, 7592–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. Multifunctional PCM composites for thermal management based on TiO2-Grown carbonized cotton and acetamide grafted Bisphenol-A. Carbon 2026, 247, 121038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, J.C.; Moriones, P.; Arzamendi, G.; Garrido, J.J.; Gil, M.J.; Cornejo, A.; Martínez-Merino, V. Kinetics of the acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) by 29Si NMR spectroscopy and mathematical modeling. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2018, 86, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zeng, C.; Yu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Preparation of hollow zeolite NaA/chitosan composite microspheres via in situ hydrolysis-gelation-hydrothermal synthesis of TEOS. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 257, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsen, K.C.; Petrik, N.G.; Dononelli, W.; Kimmel, G.A.; Xu, T.; Li, Z.; Lammich, L.; Hammer, B.; Lauritsen, J.V.; Wendt, S. Origin of hydroxyl pair formation on reduced anatase TiO2(101). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 13645–13653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadkhani, S.; Nandy, S.; Aleshkevych, P.; Chae, K.H.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Najafpour, M.M. Decomposition of a manganese complex loaded on TiO2 nanoparticles under photochemical reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Wang, W.-W.; Zhang, Q.-X.; Wu, N.; Wu, Y.; Tang, D.-L. Anchoring (fullerol-)Ru-based-complex onto TiO2 for Efficient Water Oxidation Catalysis. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, G. Phonon-engineered extreme thermal conductivity materials. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 1188–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Sun, K.; Ji, J.; Cui, G.; Hou, L.; Shi, M.; Wei, F.; Yang, W. Flexible phase change materials for overheating protection of electronics. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Fu, Y.; Yuan, J. Novel flexible phase change materials with high emissivity, low thermal conductivity and mechanically robust for thermal management in outdoor environment. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Kong, X.; Han, J.; Shi, Y. Coupling of flexible phase change materials and pipe for improving the stability of heating system. Energy 2023, 275, 127474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Li, P.; Feng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X. Using mesoporous carbon to pack polyethylene glycol as a shape-stabilized phase change material with excellent energy storage capacity and thermal conductivity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 310, 110631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, B.; Cheng, H.; Mao, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhong, Y.; Feng, X.; Yu, J.; Sui, X. Cellulosic scaffolds doped with boron nitride nanosheets for shape-stabilized phase change composites with enhanced thermal conductivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Qiu, J.; Deng, S.; Du, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wang, H. Ti3C2Tx@PDA-Integrated Polyurethane Phase Change Composites with Superior Solar-Thermal Conversion Efficiency and Improved Thermal Conductivity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 5799–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, N.; Xie, T.; Feng, Y.; Hu, P.; Li, Q.; Jiang, L.-M.; Zeng, W.-B.; Zeng, J.-L. Preparation and characterization of erythritol/sepiolite/exfoliated graphite nanoplatelets form-stable phase change material with high thermal conductivity and suppressed supercooling. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 217, 110726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, B.V.R.; Gumtapure, V. Thermo-physical analysis of natural shellac wax as novel bio-phase change material for thermal energy storage applications. J. Energy Storage 2020, 29, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z. A n-octadecane/hierarchically porous TiO2 form-stable PCM for thermal energy storage. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | TEOS | H2O | Absolute Alcohol | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Average Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 262.76 | 11.03 |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 428.44 | 8.11 |

| 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 476.14 | 8.36 |

| 4 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 418.15 | 9.59 |

| 5 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 343.79 | 8.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Zhao, G.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Yao, J.; Qiao, G.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Guo, D.; et al. A Dual-Scale Encapsulation Strategy for Phase Change Materials: GTS-PEG for Efficient Heat Storage and Release. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1887. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241887

Zhang S, Zhao G, Li Z, Zhao Z, Yao J, Qiao G, Chen Z, Wang Y, Zhang D, Guo D, et al. A Dual-Scale Encapsulation Strategy for Phase Change Materials: GTS-PEG for Efficient Heat Storage and Release. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1887. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241887

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Sixing, Guangyao Zhao, Zhen Li, Zhehui Zhao, Jiakang Yao, Geng Qiao, Zongkun Chen, Yuwei Wang, Donghui Zhang, Dongliang Guo, and et al. 2025. "A Dual-Scale Encapsulation Strategy for Phase Change Materials: GTS-PEG for Efficient Heat Storage and Release" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1887. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241887

APA StyleZhang, S., Zhao, G., Li, Z., Zhao, Z., Yao, J., Qiao, G., Chen, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, D., Guo, D., Zhu, Z., & Han, Y. (2025). A Dual-Scale Encapsulation Strategy for Phase Change Materials: GTS-PEG for Efficient Heat Storage and Release. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1887. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241887