Automated Particle Size Analysis of Supported Nanoparticle TEM Images Using a Pre-Trained SAM Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

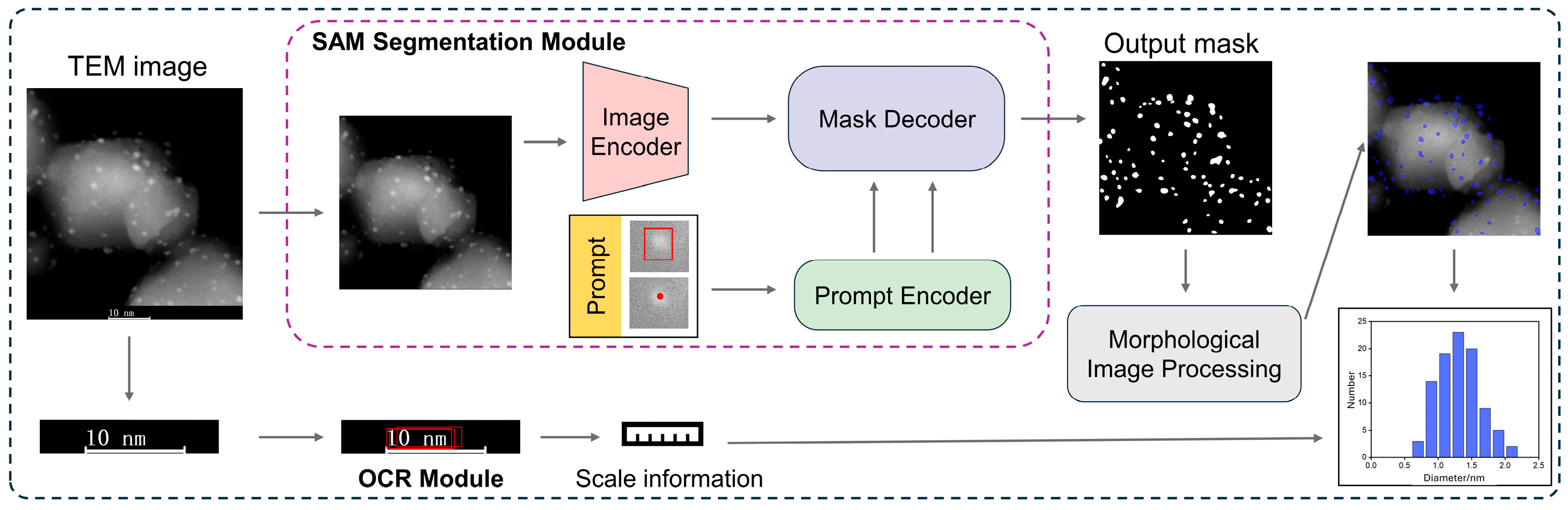

2.1. Method Overview

2.1.1. Image Segmentation Module

2.1.2. OCR and Particle Size Statistics Module

2.2. Web-Based Graphical User Interface and Prompting Workflow

2.2.1. Scale Calibration and Single-Image Mode

2.2.2. Interactive Prompts

2.2.3. Size Filtering

2.2.4. Batch Processing Mode

2.2.5. Export of Indexed Masks for Extended Morphological Analysis

2.3. Materials and Data Acquisition

2.3.1. Reagents

2.3.2. Synthesis of Materials

2.3.3. TEM Image Acquisition

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation Criteria

3.1.1. Data Configuration and Construction of Human “Consensus”

3.1.2. Core Metrics and Computations

- (1)

- Quantile Mean Absolute Percentage Error (Primary Metric)

- (2)

- Bland-Altman Consistency Analysis (Bias and Limits of Agreement (LoA))

- (3)

- Relative First-Order Wasserstein Distance (Distributional Distance ())

- (4)

- Count Consistency (Detection Rate Proxy)

- (5)

- Small-Particle Ratio Difference (Low-Contrast Sensitivity ())

3.2. Analysis and Discussion of Recognition Results

3.3. Processing Efficiency and Throughput

3.4. Reproducibility and Analytical Drift

3.5. Extended Sample Results and Discussion

3.6. Applicability and Limitations of Zero-Shot Pretrained SAM Segmentation Across Imaging Scenarios

3.7. Future Extensions: Boundary-Guided, Morphology-Aware, and Multimodal Segmentation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahmud, M.Z.A. A concise review of nanoparticles utilized energy storage and conservation. J. Nanomater. 2023, 2023, 5432099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Polaki, S.; Macrelli, A.; Casari, C.S.; Barg, S.; Jeong, S.M.; Ostrikov, K.K. Nanoparticle-enhanced multifunctional nanocarbons—Recent advances on electrochemical energy storage applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 413001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.; Iqbal, J.; Mansoor, Q.; Ahmed, I. Graphene/SiO2 nanocomposites: The enhancement of photocatalytic and biomedical activity of SiO2 nanoparticles by graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 244901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, D.S.; Upadhyay, R.P.; Shinde, G.Y.; Gawande, M.B.; Filip, J.; Varma, R.S.; Zbořil, R. A review on sustainable iron oxide nanoparticles: Syntheses and applications in organic catalysis and environmental remediation. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 7579–7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.S.; Zhang, W.; Su, D.S. Analysis of particle size distribution of supported catalyst by HAADF-STEM. Microsc. Anal. 2012, 26, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Franken, L.E.; Grünewald, K.; Boekema, E.J.; Stuart, M.C. A technical introduction to transmission electron microscopy for soft-matter: Imaging, possibilities, choices, and technical developments. Small 2020, 16, 1906198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, D.C.Y.; Sim, K.S. Single Image Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Estimation Techniques for Scanning Electron Microscope—A Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155747–155772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gao, Z.; Xiang, G.; Zhai, T.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liang, X.; Wang, L. Interfacial compatibility critically controls Ru/TiO2 metal-support interaction modes in CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, D.; Yu, K.; Rasouli, S.; Polarinakis, J.; Bovik, A.; Ferreira, P. Automatic segmentation of inorganic nanoparticles in BF TEM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 2018, 194, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, Y.; Iga, H.; Ogawa, H.; Tokuta, S.; Shimada, Y.; Yamamoto, A. Deep learning for three-dimensional segmentation of electron microscopy images of complex ceramic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, C. Precise analysis of nanoparticle size distribution in TEM image. Methods Protoc. 2023, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, S.; Hodgkinson, J.E.; Gordon, O.M.; Turner, J.; Soltoggio, A.; Moriarty, P.J.; Hunsicker, E. Improving the segmentation of scanning probe microscope images using convolutional neural networks. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 015015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, M.; Rohani, S. Particle characterization with on-line imaging and neural network image analysis. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 157, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bals, J.; Epple, M. Deep learning for automated size and shape analysis of nanoparticles in scanning electron microscopy. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 2795–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Aldrich, C. Online particle size analysis on conveyor belts with dense convolutional neural networks. Miner. Eng. 2023, 193, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.-Y. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jiao, R. Segment anything model for medical image segmentation: Current applications and future directions. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 171, 108238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhang, T.; Wei, S.; Ji, S. SAM-RSIS: Progressively adapting SAM with box prompting to remote sensing image instance segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4413814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osco, L.P.; Wu, Q.; De Lemos, E.L.; Gonçalves, W.N.; Ramos, A.P.M.; Li, J.; Junior, J.M. The segment anything model (sam) for remote sensing applications: From zero to one shot. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaravel, V.; Mathew, S.; Bartlett, J.; Pillai, S.C. Photocatalytic hydrogen production using metal doped TiO2: A review of recent advances. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 1021–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ding, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gao, F.; Dong, L.; Bao, J. Dopamine sacrificial coating strategy driving formation of highly active surface-exposed Ru sites on Ru/TiO2 catalysts in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 278, 119261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Jiang, Y.-F.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C.-Q.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Liu, B. Ruthenium/titanium oxide interface promoted electrochemical nitrogen reduction reaction. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | (%) | (mm) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 2(1a) | 1.87 | 0.0047 | 4.48 | 1.79 | −7.04 | 3.73 |

| Figure 2(2a) | 0.78 | 0.0030 | 2.09 | 0.80 | −5.00 | 0 |

| Figure 2(3a) | 1.12 | 0.0052 | 3.10 | 1.12 | −6.56 | 0.56 |

| Sample Name | (%) | (mm) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 3(1a) | 0.98 | 0.0239 | 4.8 | 1.03 | −6.38 | 4.06 |

| Figure 3(2a) | 1.26 | 0.0360 | 6.19 | 1.46 | −5.26 | 3.70 |

| Figure 3(3a) | 1.50 | 0.0396 | 8.82 | 1.46 | −8.82 | 0 |

| Figure 3(4a) | 2.46 | 0.0431 | 12.3 | 2.47 | −7.41 | 5.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, X.; Liang, G.; Meng, L.; Xi, W.; Gu, L.; Tian, N.; Zhai, Y.; He, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jin, F.; et al. Automated Particle Size Analysis of Supported Nanoparticle TEM Images Using a Pre-Trained SAM Model. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241886

Zhong X, Liang G, Meng L, Xi W, Gu L, Tian N, Zhai Y, He Y, Huang Y, Jin F, et al. Automated Particle Size Analysis of Supported Nanoparticle TEM Images Using a Pre-Trained SAM Model. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241886

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Xiukun, Guohong Liang, Lingbei Meng, Wei Xi, Lin Gu, Nana Tian, Yong Zhai, Yutong He, Yuqiong Huang, Fengmin Jin, and et al. 2025. "Automated Particle Size Analysis of Supported Nanoparticle TEM Images Using a Pre-Trained SAM Model" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241886

APA StyleZhong, X., Liang, G., Meng, L., Xi, W., Gu, L., Tian, N., Zhai, Y., He, Y., Huang, Y., Jin, F., & Gao, H. (2025). Automated Particle Size Analysis of Supported Nanoparticle TEM Images Using a Pre-Trained SAM Model. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241886