Mechanochemically Synthesized Nanocrystalline Cu2ZnSnSe4 as a Multifunctional Material for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussions

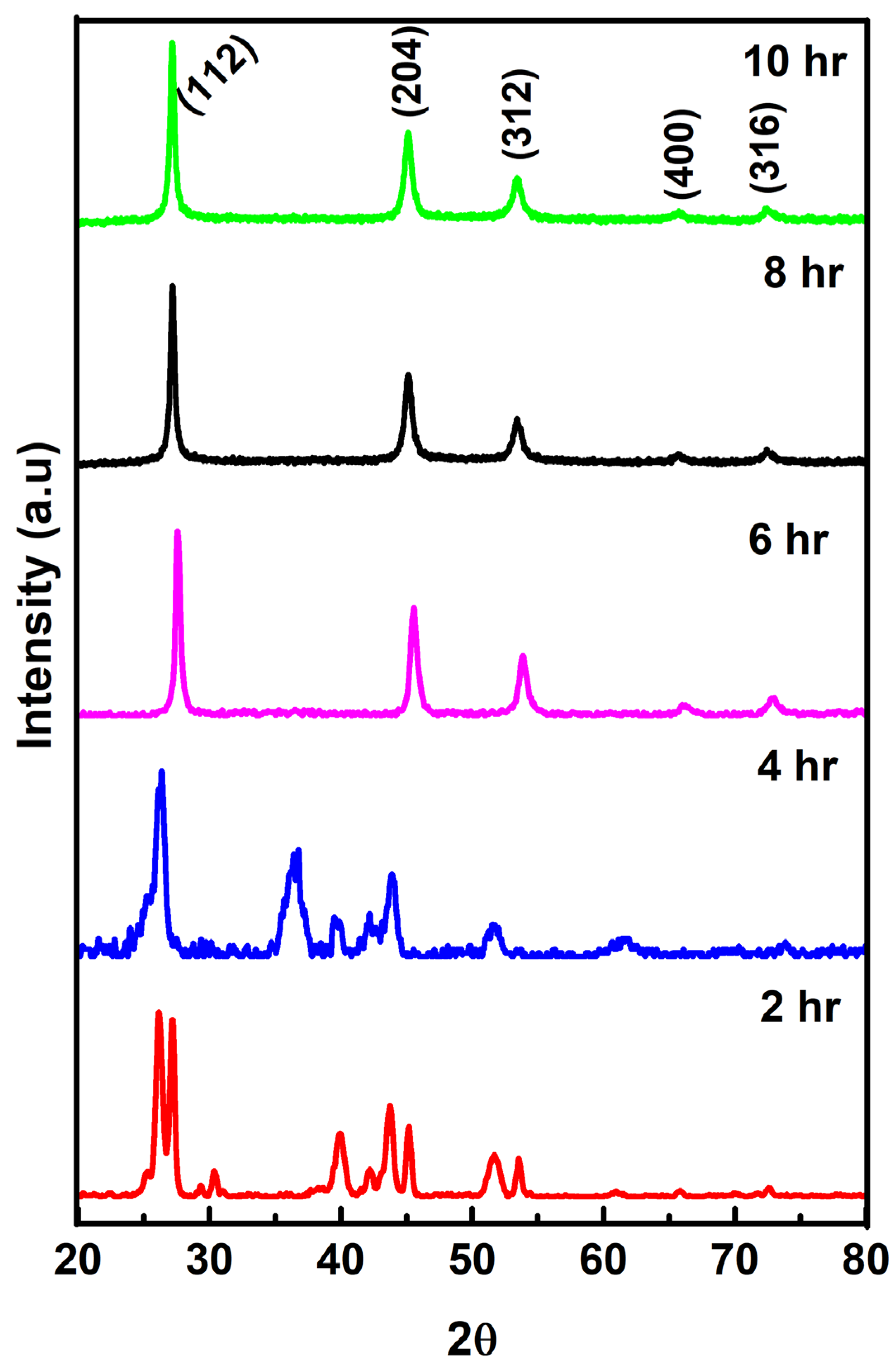

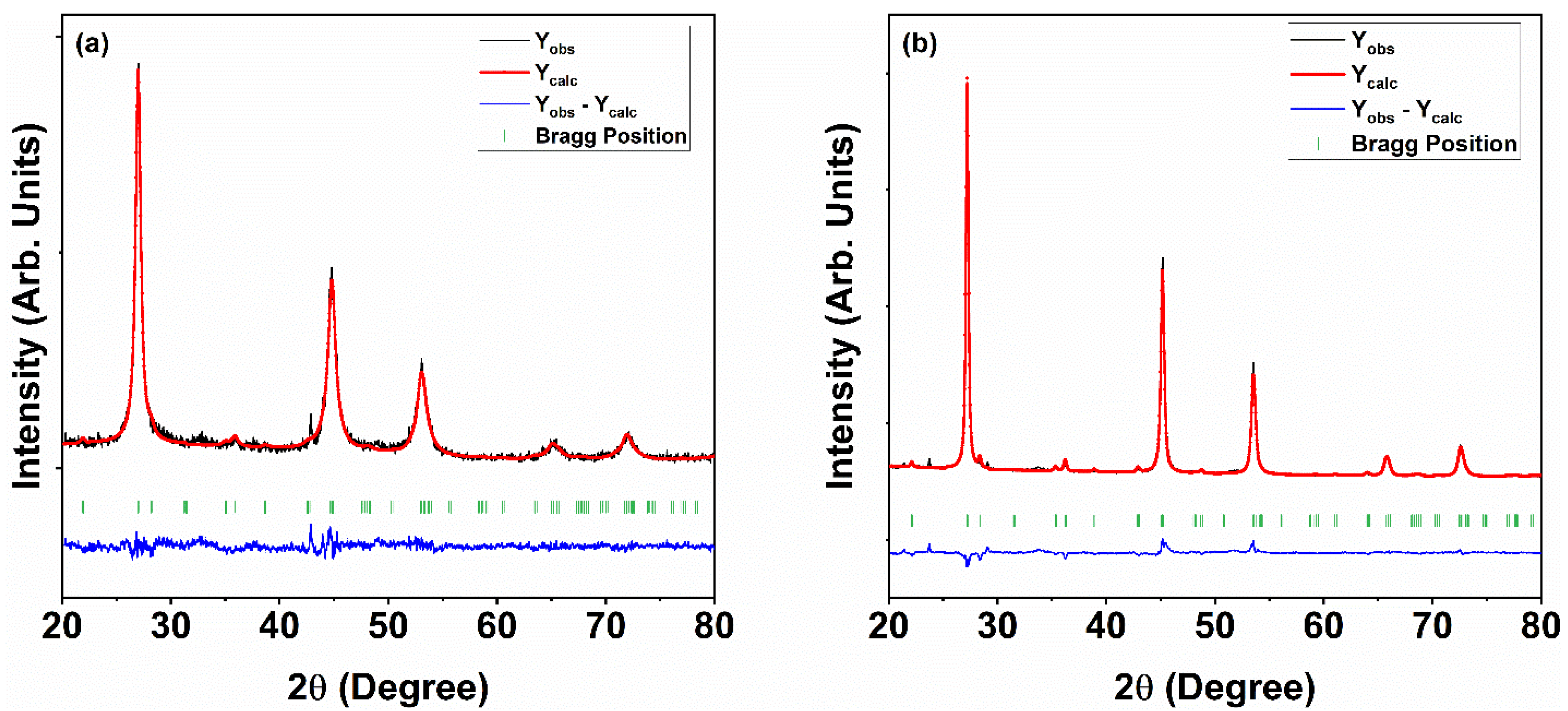

3.1. Structural Analysis

| Sample in h | 2θ (Degree) | d-Spacing (Å) | (hkl) | Crystallite Size (nm) | Dislocation Density (δ) × 1015 Lines/m2 | Strain | Lattice Parameters (a = b ≠ c) (Å) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp | Cal | |||||||||||

| Exp | Cal | Exp | Cal | a | c | a | c | |||||

| 6 | 27.37 | 27.1 | 3.236 | 3.283 | (112) | 18.6 | 2.8 | 0.031 | 5.67 | 11.26 | 5.77 | 11.48 |

| 8 | 27.2 | 27.1 | 3.245 | 3.283 | (112) | 19.6 | 2.58 | 0.030 | 5.68 | 11.28 | 5.77 | 11.48 |

| 10 | 27.16 | 27.1 | 3.278 | 3.283 | (112) | 19.9 | 2.57 | 0.030 | 5.68 | 11.29 | 5.77 | 11.48 |

| Empirical Formula | Cu2ZnSnSe4 (As Synthesized) | Cu2ZnSnSe4 (Annealed) |

|---|---|---|

| Formula weight (g/mol) | 627.03 | 627.03 |

| Temperature | RT | RT |

| Wavelength | λkα1 = 1.54056 λ kα2 = 1.54439 | λkα1 = 1.54056 λ kα2 = 1.54439 |

| 2θ step scan increment | 0.020006 | 0.020007 |

| 2θ range (°) | Min = 20.120001 | Min = 20.120001 |

| Max = 90.000000 | Max = 90.000000 | |

| Program | Fullprof | Fullprof |

| Zero-point (2θ) | 0.1732 | 0.1503 |

| Pesudo-Voigt function PV = ηL + (1 − η) G | η = 0.1923 | η = 0.0906 |

| Caglioti parameters | U = 0.08682 | U = 0.97014 |

| V =−0.11404 | V = −0.43220 | |

| W = 0.09554 | W = 0.29198 | |

| No. of refined parameters | 11 | 14 |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal | Tetragonal |

| Space group | I | I |

| a (Å) | 5.6552 | 5.6654 |

| b (Å) | 5.6552 | 5.6654 |

| c (Å) | 11.2679 | 11.4533 |

| V (Å) 3 | 360.365 | 367.739 |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Atom number | 16 | 16 |

| Rp | 4.85 | 8.15 |

| Rwp | 6.45 | 10.5 |

| Rexp | 5.06 | 8.51 |

| χ2 | 1.62 | 1.52 |

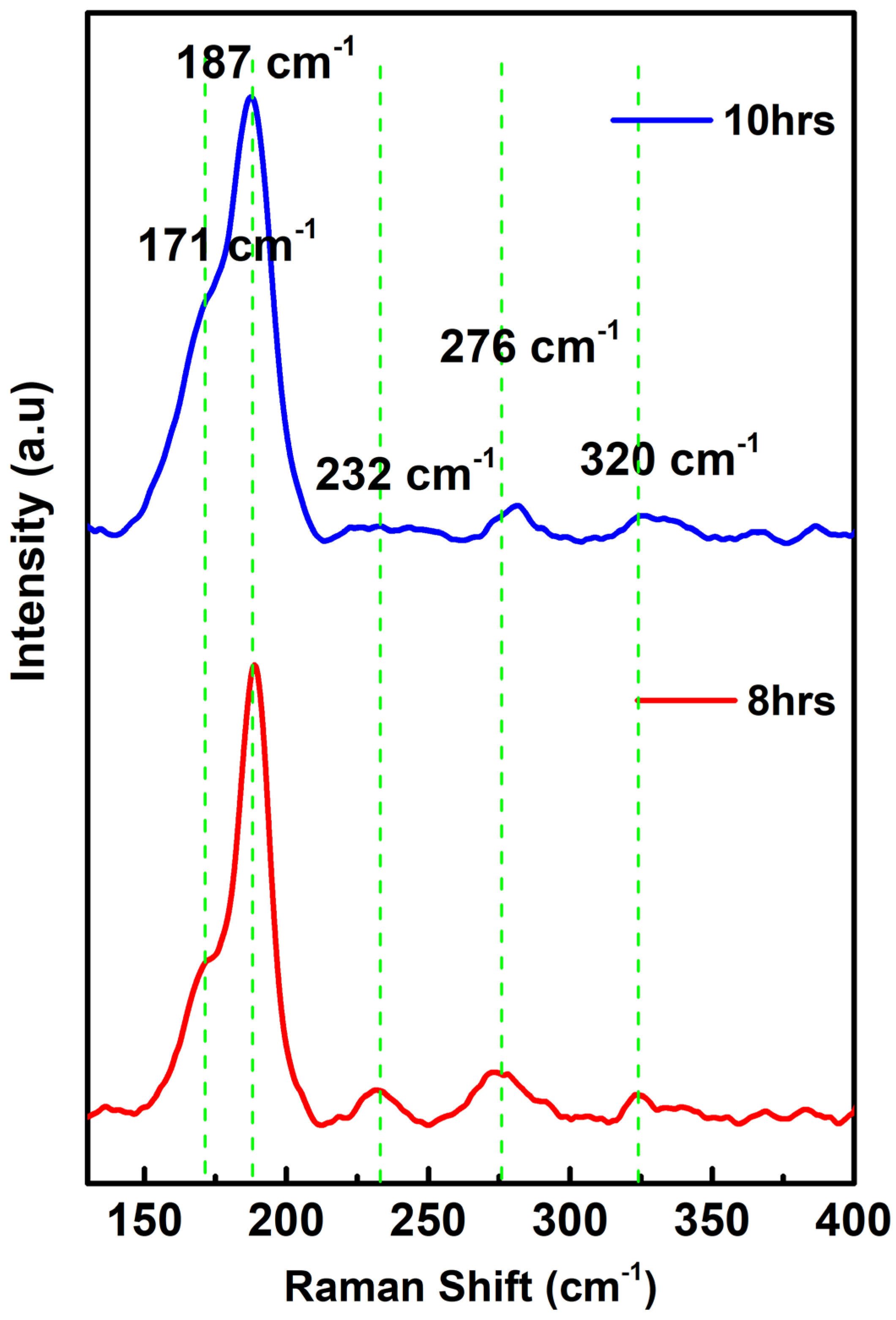

3.2. Raman Spectroscopy

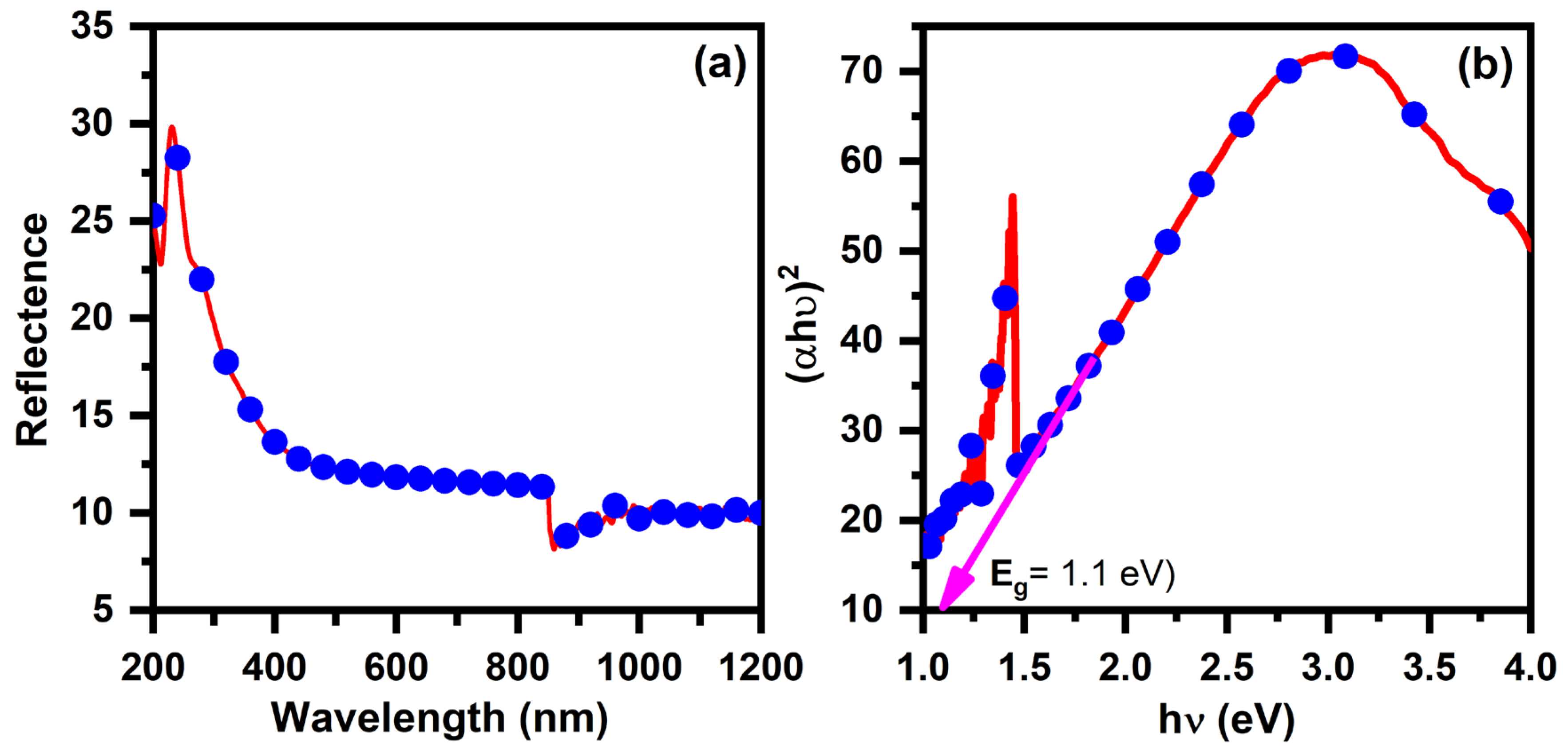

3.3. Optical Properties

3.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Analysis of Cu2ZnSnSe4

3.5. Thermal Analysis of Cu2ZnSnSe4

3.6. Surface Analysis of Cu2ZnSnSe4 Using FESEM

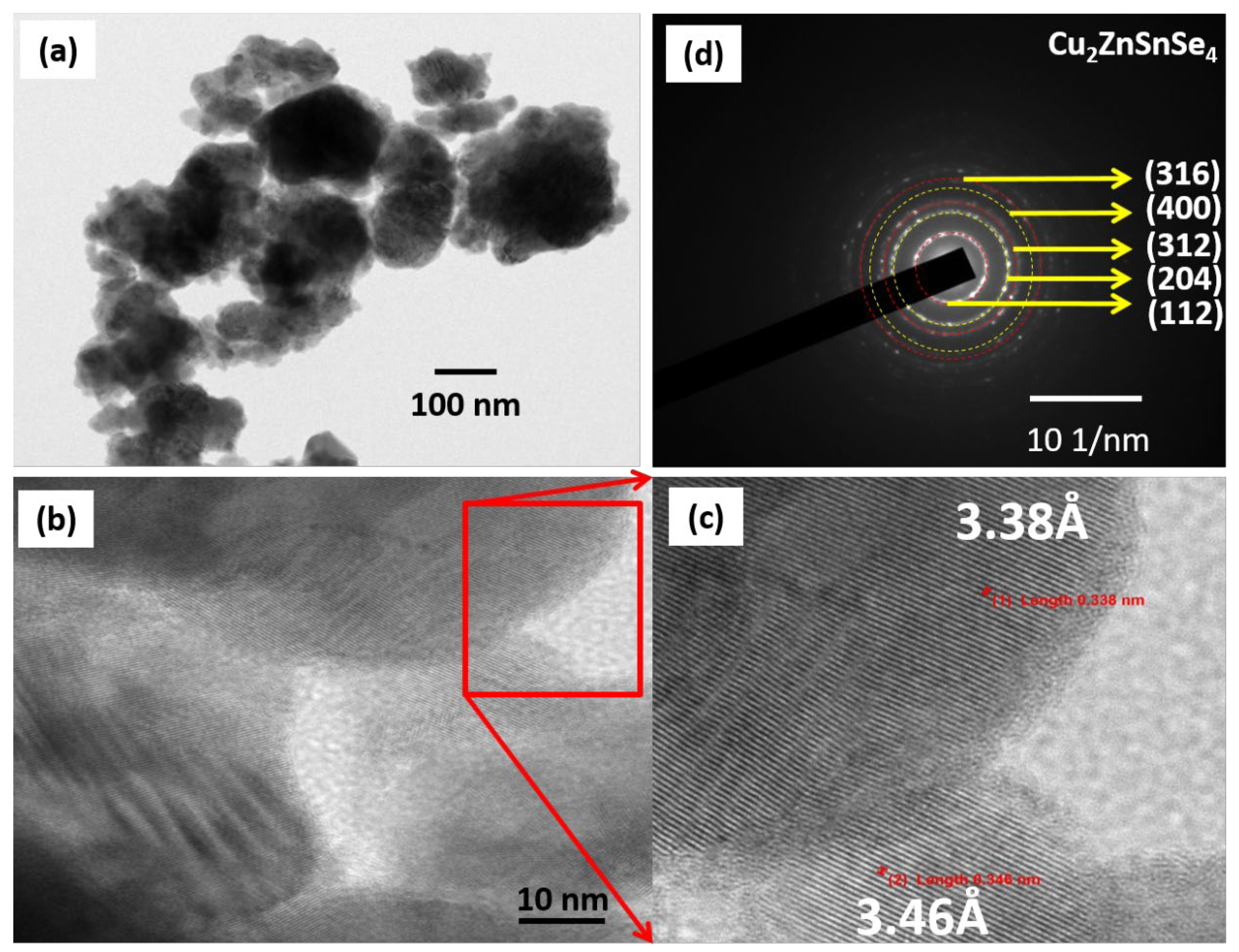

3.7. Surface Analysis of Cu2ZnSnSe4 Using HRTEM

3.8. Electrical Properties of Cu2ZnSnSe4 by Hall Effect Measurement

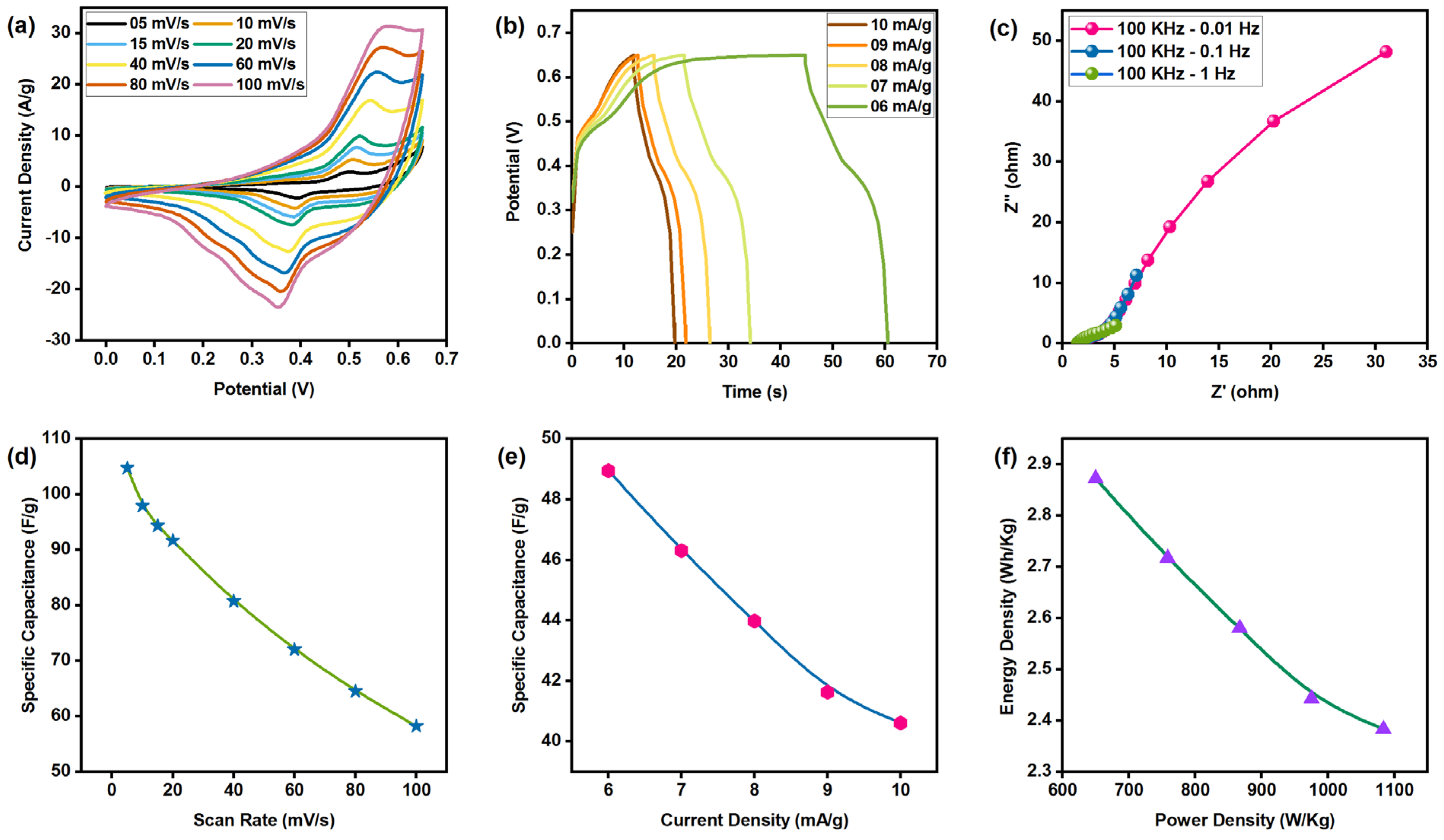

3.9. Electrochemical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wadia, C.; Alivisatos, A.P.; Kammen, D.M. Materials availability expands the opportunity for large-scale photovoltaics deployment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 2072–2077. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19368216 (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajitha, D.R.; Stephen, B.; Nakamura, A.; Selvaraj, M.; Salammal, S.T.; Hussain, S. The Emergence of Chalcogenides: A New Era for Thin Film Solar Absorbers. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2024, 76, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devika, R.S.; Vengatesh, P.; Shyju, T.S. Review on ternary chalcogenides: Potential photoabsorbers. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, T.; Kita, M.; Carda, J.; Escribano, P. Cu2ZnSnS4 films deposited by a soft-chemistry method. Thin Solid Film. 2009, 517, 2541–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Oonuki, M.; Moritake, N.; Uchiki, H. Cu2ZnSnS4 thin film solar cells prepared by non-vacuum processing. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2009, 93, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, C.; Wei, H.; Shao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Pang, S.; Cui, G. Suppressing Element Inhomogeneity Enables 14.9% Efficiency CZTSSe Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2400138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnes, J.A.; Beauno, S. Mechanosynthesis of semiconductor nanocrystalline Cu2ZnSnSe4 for solar cells. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Duan, H.-S.; Cha, K.C.; Hsu, C.-J.; Hsu, W.-C.; Zhou, H.; Bob, B.; Yang, Y. Molecular solution approach to synthesize electronic quality Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6915–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, S.M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Easy hydrothermal preparation of Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTS) nanoparticles for solar cell application. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 495401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Guo, B.; Mak, C.; Li, A.; Wu, X.; Zhang, F. Facile synthesis of ultra fi ne Cu2ZnSnS4 nanocrystals by hydrothermal method for use in solar cells. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 535, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavel, A.; Cadavid, D.; Ibáñez, M.; Carrete, A.; Cabot, A. Continuous production of Cu2ZnSnS4 nanocrystals in a flow reactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Sueishi, T.; Saito, K.; Guo, Q.; Nishio, M.; Yu, K.M.; Walukiewicz, W. Existence and removal of Cu2Se second phase in coevaporated Cu2ZnSnSe4 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 053522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Wu, L.; Gong, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.-W.; Gong, X.-G. Composition- and Band-Gap-Tunable Synthesis of Wurtzite-Derived Cu2ZnSn(S1−xSex)4 Nanocrystals: Theoretical and Experimental Insights. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Kavalakkatt, J.; Kornhuber, K.; Abou-Ras, D.; Schorr, S.; Lux-Steiner, M.C.; Ennaoui, A. Synthesis of Cu2ZnxSnySe1+x+2y nanocrystals with wurtzite-derived structure. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 9894–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, T.; Gou, B. High-Efficiency Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Based on Kesterite Cu2ZnSnSe4 Inlaid on a Flexible Carbon Fabric Composite Counter Electrode. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 24898–24905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scragg, J.J.; Dale, P.J.; Peter, L.M. Towards sustainable materials for solar energy conversion: Preparation and photoelectrochemical characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.K.; Gusain, M.; Thangriyal, S.; Nagarajan, R.; Rao, G.R. Energy storage study of trimetallic Cu2MSnS4 (M: Fe, Co, Ni) nanomaterials prepared by sequential crystallization method. J. Solid State Chem. 2020, 282, 121049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palchoudhury, S.; Ramasamy, K.; Gupta, A. Multinary copper-based chalcogenide nanocrystal systems from the perspective of device applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 3069–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xi, L.; Fan, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L. Cu−Se Bond Network and Thermoelectric Compounds with Complex Diamondlike Structure. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 6029–6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M.; Cadavid, D.; Zamani, R.; García-Castelló, N.; Izquierdo-Roca, V.; Li, W.; Fairbrother, A.; Prades, J.D.; Shavel, A.; Arbiol, J.; et al. Composition control and thermoelectric properties of quaternary chalcogenide nanocrystals: The case of stannite Cu2CdSnSe4. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Aslam, S.; Awais, M.; Mirza, M.; Safdar, M. Construction of Quaternary Chalcogenide Ag2BaSnS4 Nanograins for HER/OER Performances and Supercapacitor Applications in Alkaline Media. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 6531–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Howli, P.; Das, B.; Das, N.S.; Samanta, M.; Das, G.C.; Chattopadhyay, K.K. Novel Quaternary Chalcogenide/Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Asymmetric Supercapacitor with High Energy Density. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 22652–22664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Yin, P.; Zhu, H.; Li, Q. Synthesis and Photoelectric Properties of Cu2ZnGeS4 and Cu2ZnGeSe4 Single-Crystalline Nanowire Arrays. Langmuir 2013, 29, 8713–8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, N.M.; Lokhande, C.D.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, J.H. Low cost and large area novel chemical synthesis of Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTS) thin films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2012, 235, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, J.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; Hu, Z.; Huang, S. Wet chemical route to the synthesis of kesterite Cu2ZnSnS4 nanocrystals and their applications in lithium ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2013, 92, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Hwang, Y.H.; Bae, B.S. Sol-gel processed Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films for a photovoltaic absorber layer without sulfurization. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2013, 65, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakuphanoglu, F. Nanostructure Cu2ZnSnS4 thin film prepared by sol–gel for optoelectronic applications. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 2518–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, K.; Watabe, J.; Tanaka, K.; Uchiki, H. Characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films prepared by photo-chemical deposition. Phys. Status Solidi Curr. Top. Solid State Phys. 2006, 3, 2848–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exarhos, S.; Bozhilov, K.N.; Mangolini, L. Spray pyrolysis of CZTS nanoplatelets. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11366–11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daranfed, W.; Aida, M.S.; Attaf, N.; Bougdira, J.; Rinnert, H. Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films deposition by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 542, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, K.; Malik, M.A.; O’Brien, P. The chemical vapor deposition of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1170–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gunawan, O.; Todorov, T.; Shin, B.; Chey, S.J.; Bojarczuk, N.A.; Mitzi, D.; Guha, S. Thermally evaporated Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 143508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Shi, G.; Chen, Z.; Yang, P.; Yao, M. Deposition of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films by vacuum thermal evaporation from single quaternary compound source. Mater. Lett. 2012, 73, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Cai, J.; Shen, B.; Ren, Y.; Qin, G. Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films: Facile and cost-effective preparation by RF-magnetron sputtering and texture control. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 552, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionna, S.; Garattini, P.; Donne, A.L.; Acciarri, M.; Tombolato, S.; Binetti, S. Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells grown by sulphurisation of sputtered metal precursors. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 542, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Ras, D.; Kirchartz, T. Electron-Beam-Induced Current Measurements of Thin-Film Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 6127–6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanalakar, S.A.; Agawane, G.L.; Shin, S.W.; Suryawanshi, M.P.; Gurav, K.V.; Jeon, K.S.; Patil, P.S.; Jeong, C.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. A review on pulsed laser deposited CZTS thin films for solar cell applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 619, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimsen, E.; Riha, S.C.; Baryshev, S.V.; Martinson, A.B.F.; Elam, J.W.; Pellin, M.J. atomic Layer Deposition of the Quaternary Chalcogenide Cu2ZnSnS4. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 3188–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, T.K.; Reuter, K.B.; Mitzi, D.B. High-efficiency solar cell with earth-abundant liquid-processed absorber. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kang, X.; Huang, L.; Wei, S.; Pan, D. Facile and Low-Cost Sodium-Doping Method for High-Efficiency Cu2ZnSnSe4 Thin Film Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 22797–22802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, N.; Gremenok, V.F.; Zaretskaya, E.P.; Ozcelik, S. Investigation on the properties of Cu2ZnSnSe4 and Cu2ZnSn (S,Se)4 absorber films prepared by magnetron sputtering technique using Zn and ZnS targets in precursor stacks. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 2398–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hages, C.J.; Koeper, M.J.; Miskin, C.K.; Brew, K.W.; Agrawal, R. Controlled Grain Growth for High Performance Nanoparticle-Based Kesterite Solar Cells. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 7703–7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinella, M.; Inguanta, R.; Spanò, T.; Livreri, P.; Piazza, S.; Sunseri, C. Electrochemical deposition of CZTS thin films on flexible substrate. Energy Procedia 2014, 44, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangperawong, A.; King, J.S.; Herron, S.M.; Tran, B.P.; Pangan-Okimoto, K.; Bent, S.F. Aqueous bath process for deposition of Cu2ZnSnS4 photovoltaic absorbers. Thin Solid Film. 2011, 519, 2488–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Guo, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y. Investigation on the Structure and Morphology of CZTSe Solar Cells by Adjusting Cu–Ge Buffer Layers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 11793–11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baláž, P.; Hegedüs, M.; Achimovičová, M.; Baláž, M.; Tešinský, M.; Dutková, E.; Kaňuchová, M.; Briančin, J. Semi-industrial Green Mechanochemical Syntheses of Solar Cell Absorbers Based on Quaternary Sulfides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2132–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnes J, A.; Sajitha, D.R.; Beauno, S.; Selvaraj, M.; Salammal, S.T. Efficient mechanochemical studies of Cu2FeSnSe4 quaternary chalcogenide for energy conversion and storage applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 173, 113881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Smallman, R.E., III. Dislocation densities in some annealed and cold-worked metals from measurements on the X-ray debye-scherrer spectrum. Philos. Mag. 1956, 1, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M.; Zamani, R.; Li, W.; Shavel, A.; Arbiol, J.; Morante, J.R.; Cabot, A. Extending the nanocrystal synthesis control to quaternary compositions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immanuel, A.; Agnes J, A.; Sajitha, D.R.; Mosas, K.K.A.; Govindasamy, C.; Almutairi, K.M.; Beauno, S.; Salammal, S.T. Exploration of structural and optoelectronic behaviour of mechanochemically synthesized earth-abundant phase pure Cu2FeSnSe4. Mater. Res. Bull. 2025, 189, 113477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martínez, A.; Placidi, M.; Arqués, L.; Giraldo, S.; Sánchez, Y.; Izquierdo-Roca, V.; Pistor, P.; Valentini, M.; Malerba, C.; Saucedo, E. Insights into the Formation Pathways of Cu2ZnSnSe4 Using Rapid Thermal Processes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Park, B.I.; Lee, B.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, H.; Ko, M.J.; Kim, B.; Son, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Influences of extended selenization on Cu2ZnSnSe4 solar cells prepared from quaternary nanocrystal ink. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 27657–27663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Xie, C.; Yang, Z. Design of Infrared Nonlinear Optical Compounds with Diamond-like Structures and Balanced Optical Performance. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 11454–11462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadka, D.B.; Kim, J.H. Band gap engineering of alloyed Cu2ZnGexSn1−xQ4 (Q = S,Se) films for solar cell. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, W.; Tian, Q.; Huang, L.; Pan, D. Solution-processed highly efficient Cu2ZnSnSe4 thin film solar cells by dissolution of elemental Cu, Zn, Sn, and Se Powders. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Label | 1/2r (nm−1) | 1/r (nm−1) | r (nm) | d—Spacing (Å) | (hkl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM (Obs) | Standard | |||||

| 1 | 5.844 | 2.922 | 0.342 | 3.42 | 3.31 | (112) |

| 2 | 9.742 | 4.871 | 0.205 | 2.05 | 2.08 | (204) |

| 3 | 11.518 | 5.759 | 0.173 | 1.73 | 1.736 | (312) |

| 4 | 13.442 | 6.721 | 0.148 | 1.48 | 1.442 | (400) |

| 5 | 15.195 | 7.5975 | 0.131 | 1.31 | 1.312 | (316) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnrose, A.A.; Rajan Sajitha, D.; Panneerselvam, V.; Sivaramalingam, A.; Amirtharaj Mosas, K.K.; Stephen, B.; Thankaraj Salammal, S. Mechanochemically Synthesized Nanocrystalline Cu2ZnSnSe4 as a Multifunctional Material for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241866

Johnrose AA, Rajan Sajitha D, Panneerselvam V, Sivaramalingam A, Amirtharaj Mosas KK, Stephen B, Thankaraj Salammal S. Mechanochemically Synthesized Nanocrystalline Cu2ZnSnSe4 as a Multifunctional Material for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241866

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnrose, Angel Agnes, Devika Rajan Sajitha, Vengatesh Panneerselvam, Anandhi Sivaramalingam, Kamalan Kirubaharan Amirtharaj Mosas, Beauno Stephen, and Shyju Thankaraj Salammal. 2025. "Mechanochemically Synthesized Nanocrystalline Cu2ZnSnSe4 as a Multifunctional Material for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241866

APA StyleJohnrose, A. A., Rajan Sajitha, D., Panneerselvam, V., Sivaramalingam, A., Amirtharaj Mosas, K. K., Stephen, B., & Thankaraj Salammal, S. (2025). Mechanochemically Synthesized Nanocrystalline Cu2ZnSnSe4 as a Multifunctional Material for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241866