Low-Temperature Synthesis of Highly Preferentially Oriented ε-Ga2O3 Films for Solar-Blind Detector Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Thin Film Fabrication and Characterization

2.2. Device Preparation and Testing

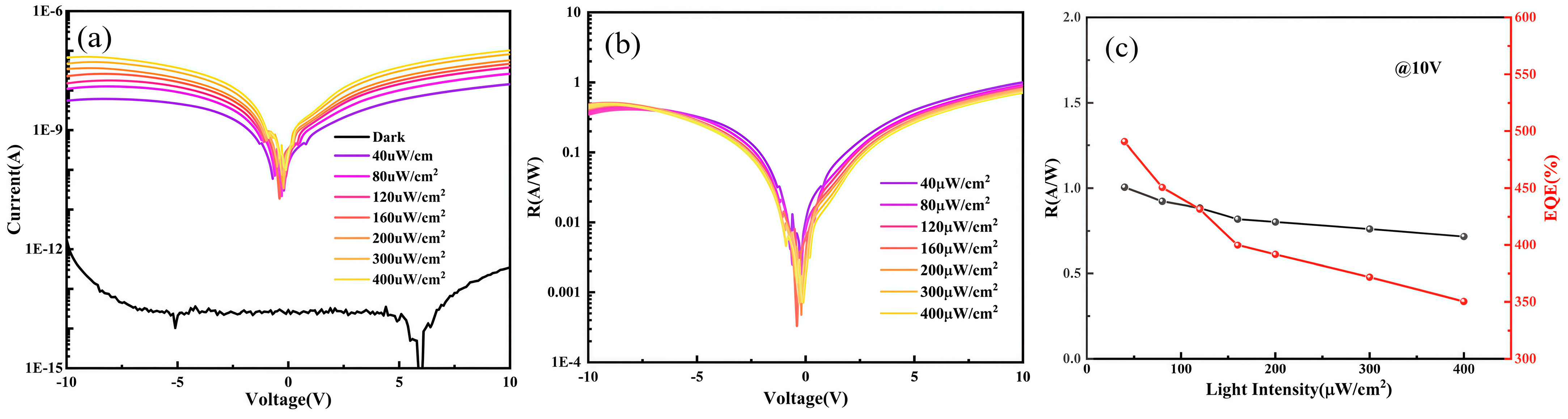

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheoran, H.; Kumar, V.; Singh, R. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Developments in Ohmic and Schottky Contacts on Ga2O3 for Device Applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 2589–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouketcha, F.L.L.; Cui, Y.; Lelis, A.; Green, R.; Darmody, C.; Schuster, J.; Goldsman, N. Investigation of Wide- and Ul- trawide-Bandgap Semiconductors from Impact-Ionization Coefficients. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2020, 67, 3999–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivani; Sharma, N.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, M. Low resistance ohmic contact of multi-metallic Mo/Al/Au stack with ultra-wide bandgap Ga2O3 thin film with post-annealing and its in-depth interface studies for next-generation high-power devices. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yan, T.; Li, C.; Tian, H.; Wang, H.; Ye, Z.-G.; Ren, W.; Niu, G. Growth of Zn-N Co-Doped Films by a New Scheme with Enhanced Optical Properties. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Shen, Y.; Ma, H.P. Research Progress on Performance Optimization of Ga2O3 SBD. In Proceedings of the 20th China International Forum on Solid State Lighting & 2023 9th International Forum on Wide Bandgap Semiconductors, Miami, FL, USA, 18–20 December 2024; pp. 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Labed, M.; Sengouga, N.; Prasad, C.V.; Henini, M.; Rim, Y.S. On the nature of majority and minority traps in β-Ga2O3: A review. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 36, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C.V.; Rim, Y.S. Review on interface engineering of low leakage current and on-resistance for high-efficiency Ga2O3-based power devices. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 27, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, I.; Ellis, H.D.; Chang, C.; Mudiyanselage, D.H.; Xu, M.; Da, B.; Fu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, K. Epitaxial Growth of Ga2O3: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Hu, Z.; Ma, J.; Yao, Y.; Cui, C.; Zuo, Y.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Research on the crystal phase and orientation of Ga2O3 Hetero-epitaxial film. Superlattices Microstruct. 2021, 159, 107053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, R.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, E.; Jia, C.; Shi, Z.; Xu, T.; Tian, Y.; Li, X. A self-powered solar-blind photodetector based on a MoS2/β-Ga2O3 heterojunction. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 10982–10986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhi, Y.-S.; Zhang, M.-L.; Yang, L.-L.; Li, S.; Yan, Z.-Y.; Zhang, S.-H.; Guo, D.-Y.; Li, P.-G.; Guo, Y.-F.; et al. A 4 × 4 metal-semiconductor-metal rectangular deep-ultraviolet detector array of Ga2O3 photoconductor with high photo response. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 088503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor-Monroy, M.I.; Murillo-Borjas, B.L.; Quevedo-Lopez, M.A. Nanocrystalline and polycrystalline β-Ga2O3 thin films for deep ultraviolet detectors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 3358–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Han, K.; Zhao, X.; Feng, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zou, Y.; Hou, X.; et al. Structure engineering of photodetectors: A review. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 063003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhao, T.; He, H.; Hu, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Q.; Liu, A.; Wu, F.; et al. Enhanced Performance of Gallium-Based Wide Bandgap Oxide Semiconductor Heterojunction Photodetector for Solar-Blind Optical Communication via Oxygen Vacancy Electrical Activity Modulation. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2302294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarik, L.; Mändar, H.; Kozlova, J.; Tarre, A.; Aarik, J. Atomic Layer Deposition of Ga2O3 from GaI3 and O3: Growth of High-Density Phases. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 5899–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschi, F.; Bosi, M.; Berzina, T.; Buffagni, E.; Ferrari, C.; Fornari, R. Hetero-epitaxy of ε-Ga2O3 layers by MOCVD and ALD. J. Cryst. Growth 2016, 443, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cora, I.; Mezzadri, F.; Boschi, F.; Bosi, M.; Caplovicová, M.; Calestani, G.; Dódony, I.; Pécz, B.; Fornari, R. The real structure of ε-Ga2O3 and its relation to κ-phase. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Jiang, K.; Tseng, P.-S.; Kurchin, R.C.; Porter, L.M.; Davis, R.F. Thermal stability and phase transformation of α-, κ(ε)-, and γ-Ga2O3 films under different ambient conditions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 092104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornari, R.; Pavesi, M.; Montedoro, V.; Klimm, D.; Mezzadri, F.; Cora, I.; Pécz, B.; Boschi, F.; Parisini, A.; Baraldi, A.; et al. Thermal stability of ε-Ga2O3 polymorph. Acta Mater. 2017, 140, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado Filho, M.A.; Farmer, W.; Hsiao, C.-L.; dos Santos, R.B.; Hultman, L.; Birch, J.; Ankit, K.; Gueorguiev, G.K. Density Functional Theory-Fed Phase Field Model for Semiconductor Nanostructures: The Case of Self-Induced Core-Shell InAlN Nanorods. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 4717–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Kuang, Y.; Hao, J.; Ren, F.-F.; Gu, S.; Zhang, R.; Ye, J. Unlocking the Single-Domain Heteroepi-taxy of Orthorhombic κ-Ga2O3 via Phase Engineering. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 4, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzadri, F.; Calestani, G.; Boschi, F.; Delmonte, D.; Bosi, M.; Fornari, R. Crystal Structure and Ferroelectric Properties of ε-Ga2O3 Films Grown on (0001)-Sapphire. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 12079–12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Jiang, K.; Choi, Y.; Aronson, B.L.; Shetty, S.; Tang, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Kelley, K.P.; Rayner, G.B.; et al. High field dielectric response in κ-Ga2O3 films. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 134, 204101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneiß, M.; Hassa, A.; Splith, D.; Sturm, C.; von Wenckstern, H.; Schultz, T.; Koch, N.; Lorenz, M.; Grundmann, M. Tin-assisted heteroepitaxial PLD-growth of κ-Ga2O3 thin films with high crystalline quality. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 022516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, H.; Xia, X.; Tao, P.; Shen, R.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Du, G. The lattice distortion of β-Ga2O3 film grown on c-plane sapphire. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 3231–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-J.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, S.Y.; Ning, R.; Kim, M.-S.; Jung, S.-J.; Won, S.O.; Baek, S.-H.; Jang, J.-S. Epitaxial Growth of β-Ga2O3 Thin Films on Si with YSZ Buffer Layer. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 43603–43608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.-Y.; Li, S.; Qi, S.; Ji, X.-Q.; Wu, Z.-P.; Li, P.-G.; Tang, W.-H. Proton Irradiation Effects in MOCVD Grown and Thin Films. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2024, 71, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarik, L.; Mandar, H.; Kasikov, A.; Tarre, A.; Aarik, J. Optical properties of thin films grown by atomic layer deposition using as precursors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 10562–10574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-C.; Ye, G.; Nnokwe, C.; Kuryatkov, V.; Warzywoda, J.; de Peralta, L.G.; He, R.; Bernussi, A. Deep Ultraviolet Optical Anisotropy of β-Gallium Oxide Thin Films. Acs Omega 2024, 9, 27963–27968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-H.; Wu, W.-Y.; Lin, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-H.; Liu, P.-L.; Hsiao, C.-L.; Horng, R.-H. ε-Ga2O3 Grown on c-Plane Sapphire by MOCVD with a Multistep Growth Process. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xia, X.; Liang, H.; Abbas, Q.; Liu, Y.; Du, G. Growth Pressure Controlled Nucleation Epitaxy of Pure Phase ε- and β-Ga2O3 Films on Al2O3 via Metal–Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xing, Y.; Han, J.; Li, J.; He, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B. Crystalline properties of ε-Ga2O3 film grown on c- sapphire by MOCVD and solar-blind ultraviolet photodetector. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 123, 105532–105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Ahn, H.; Kim, K.; Yang, M. Formation of High-Quality Heteroepitaxial β-Ga2O3 Films by Crystal Phase Transition. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2020, 56, 2000149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Jeon, J.; Ryu, S.H.; Chung, H.K.; Jang, M.; Lee, S.; Chung, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. Atomic Layer Growth of Rutile TiO2 Films with Ultrahigh Dielectric Constants via Crystal Orientation Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 33877–33884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pung, S.-Y.; Choy, K.-L.; Hou, X.; Shan, C. Preferential growth of ZnO thin films by the atomic layer deposition technique. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 435609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Properties | β-Ga2O3 Thin Film Growth | ε-Ga2O3 Thin Film Growth | Associated Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamics | Stable phase | Metastable phase | ε-phase is inherently prone to transform into β-phase |

| Growth Window | Broad | Extremely narrow | Requires highly precise parameter control |

| Temperature Control | Large-temperature growth window | Narrow-temperature growth window | Susceptible to phase transformation |

| Phase Purity | High-purity phase readily achievable | Highly prone to phase separation | Phase purity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liao, D.; Di, J.; Liu, C.; Ren, W.; Ye, Z.-G. Low-Temperature Synthesis of Highly Preferentially Oriented ε-Ga2O3 Films for Solar-Blind Detector Application. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241867

Tian H, Zhang Y, Wang H, Liao D, Di J, Liu C, Ren W, Ye Z-G. Low-Temperature Synthesis of Highly Preferentially Oriented ε-Ga2O3 Films for Solar-Blind Detector Application. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241867

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, He, Yijun Zhang, Hong Wang, Daogui Liao, Jiale Di, Chao Liu, Wei Ren, and Zuo-Guang Ye. 2025. "Low-Temperature Synthesis of Highly Preferentially Oriented ε-Ga2O3 Films for Solar-Blind Detector Application" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241867

APA StyleTian, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Liao, D., Di, J., Liu, C., Ren, W., & Ye, Z.-G. (2025). Low-Temperature Synthesis of Highly Preferentially Oriented ε-Ga2O3 Films for Solar-Blind Detector Application. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241867