The Regulating Role of Nano-SiO2 Potential in the Thermophysical Properties of NaNO3-KNO3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Sample Preparation

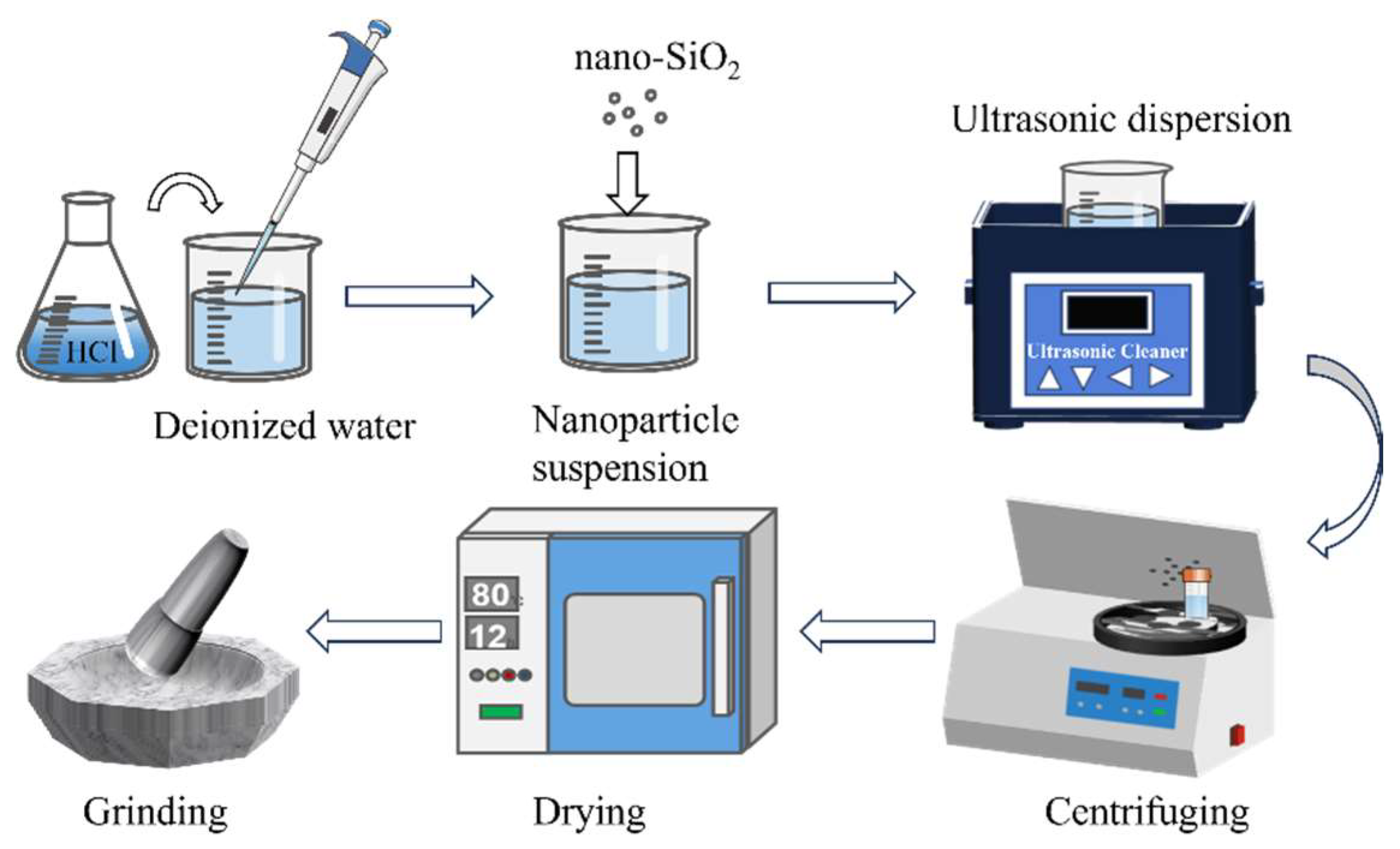

2.1.1. Modification of Nano-SiO2

2.1.2. Preparation of Composite Materials

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Zeta Potential

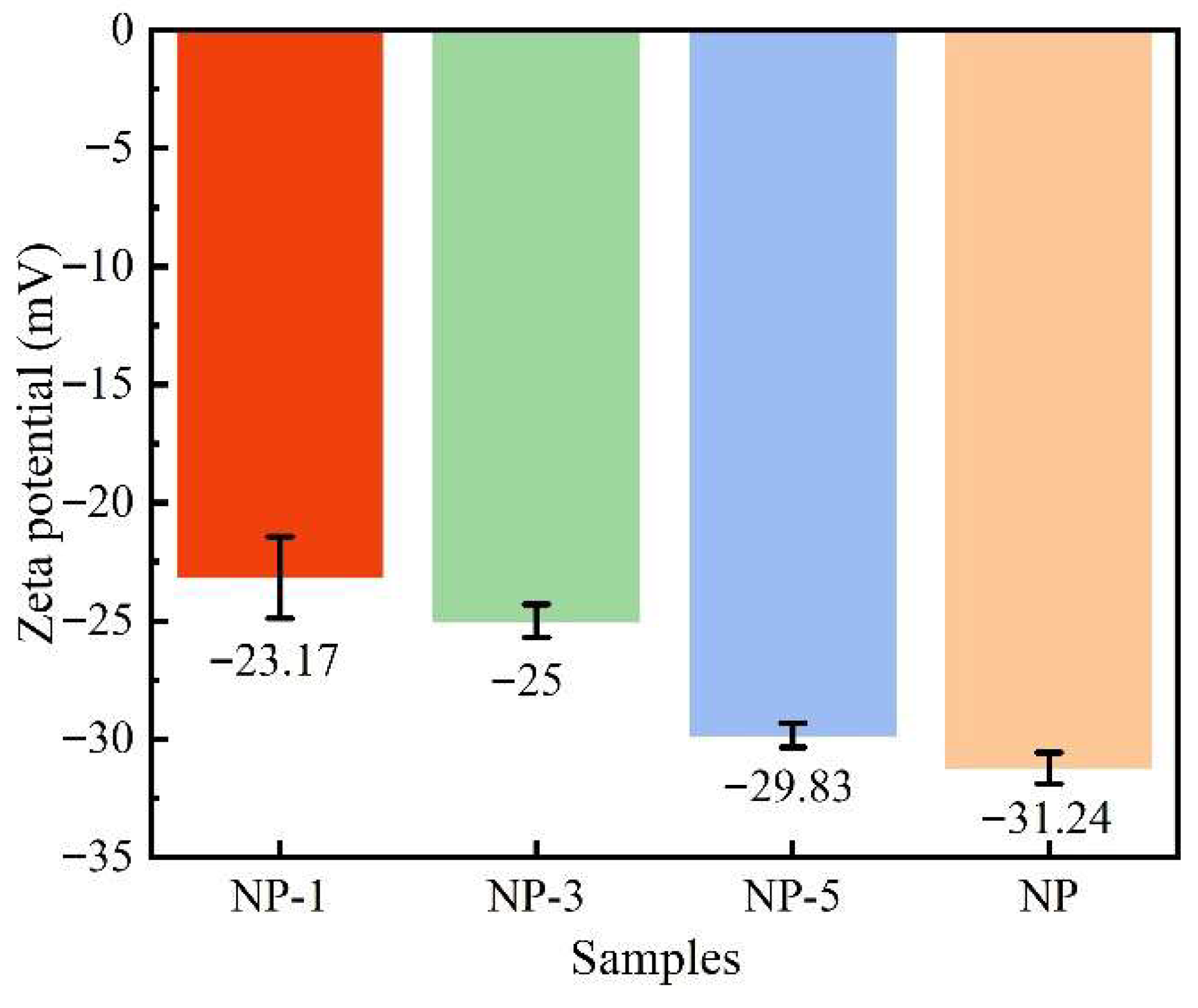

2.2.2. Morphology and Elemental Content of Nanoparticles

2.2.3. Thermal Storage Properties of MNs

2.2.4. Heat Transfer Properties of MNs

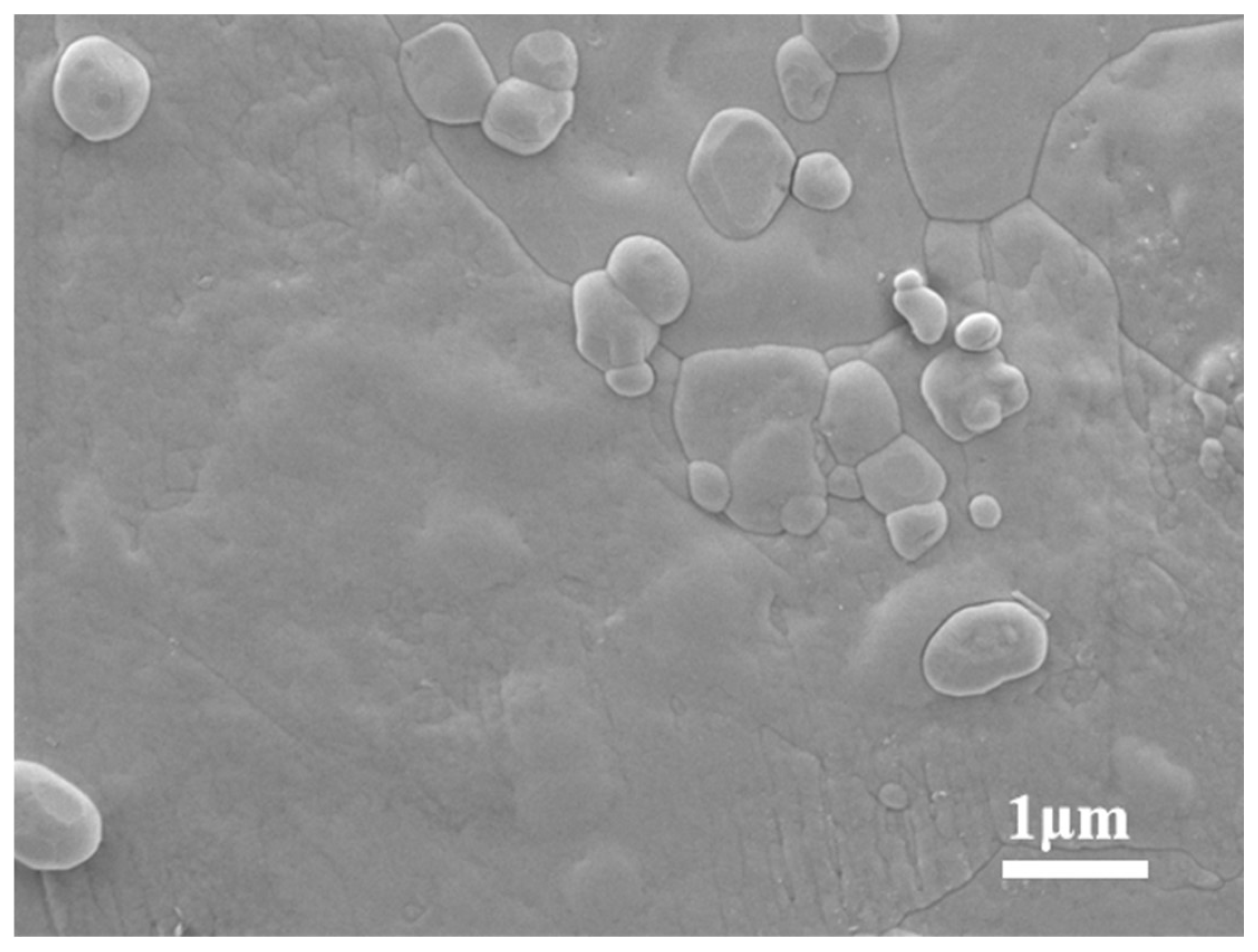

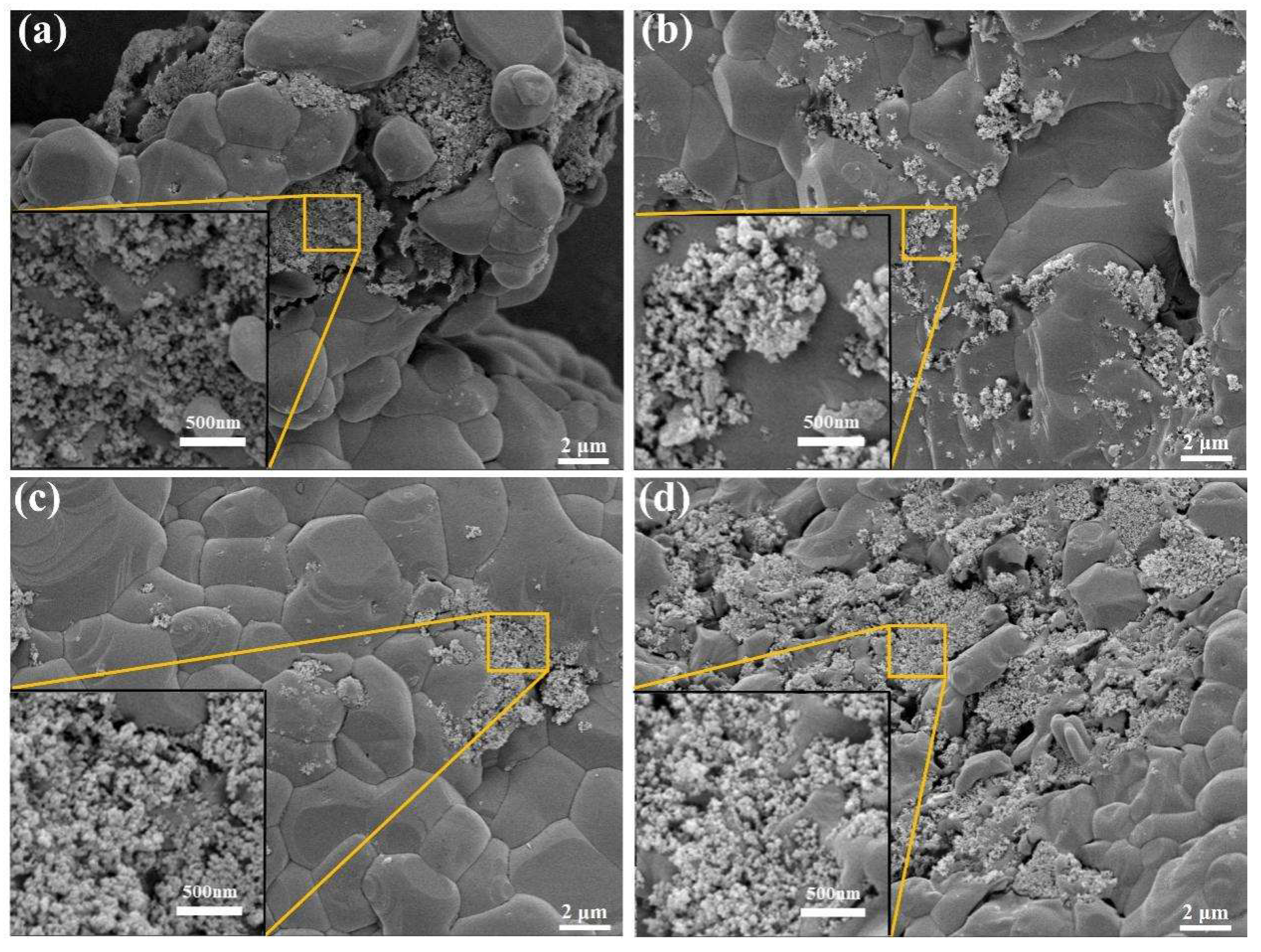

2.2.5. Micro-Morphological Characterisation of MNs

3. Results and Discussion

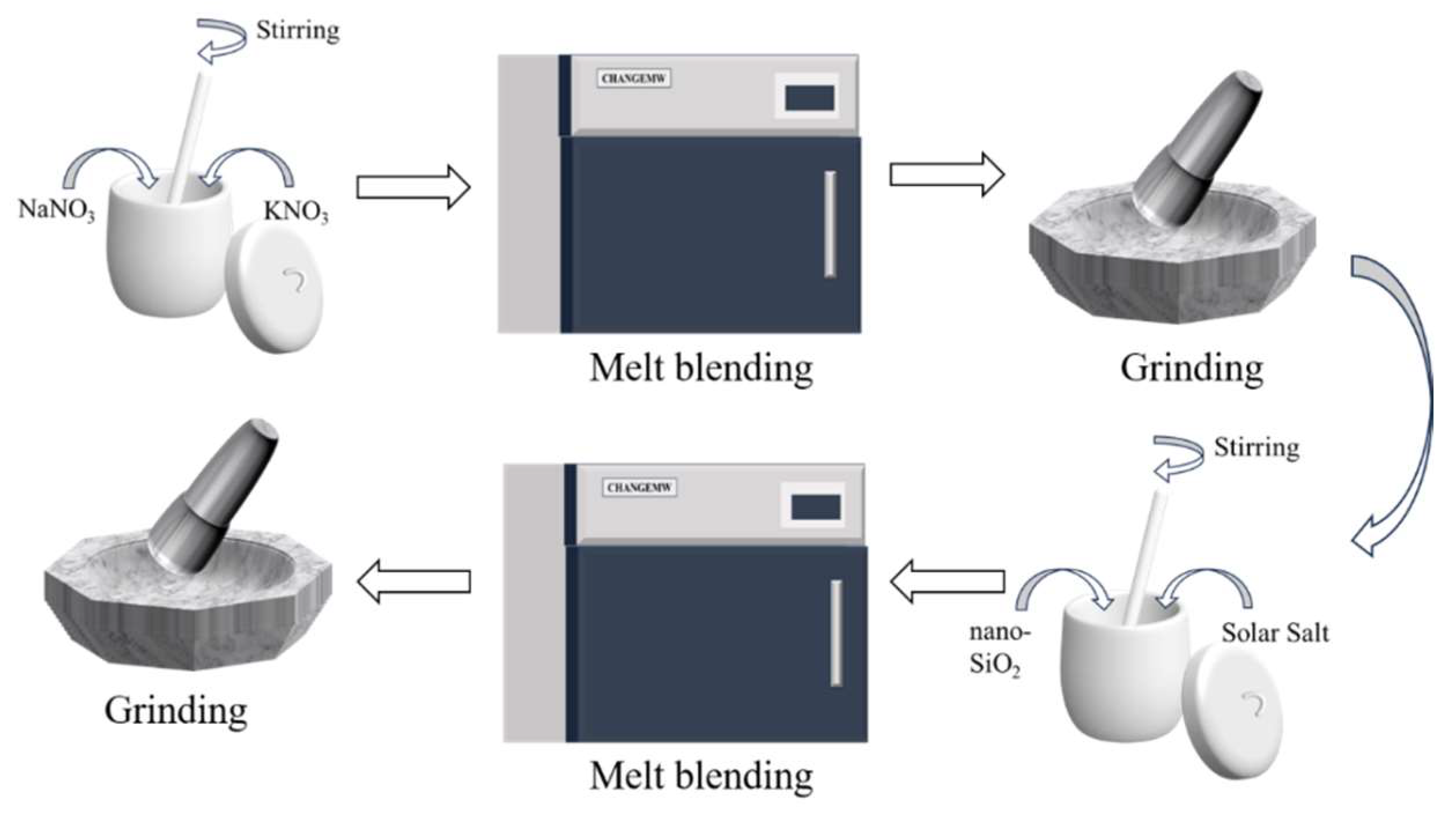

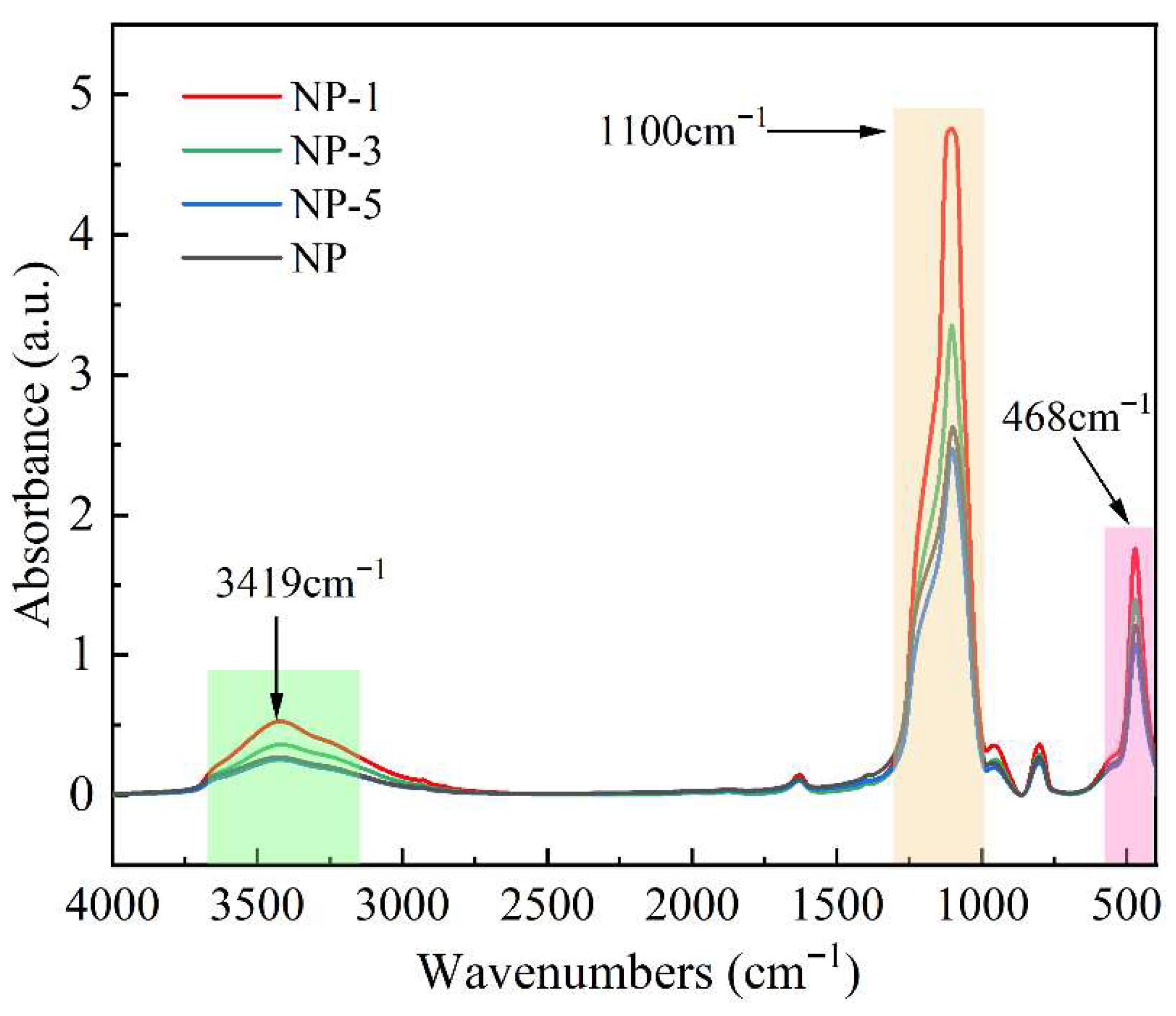

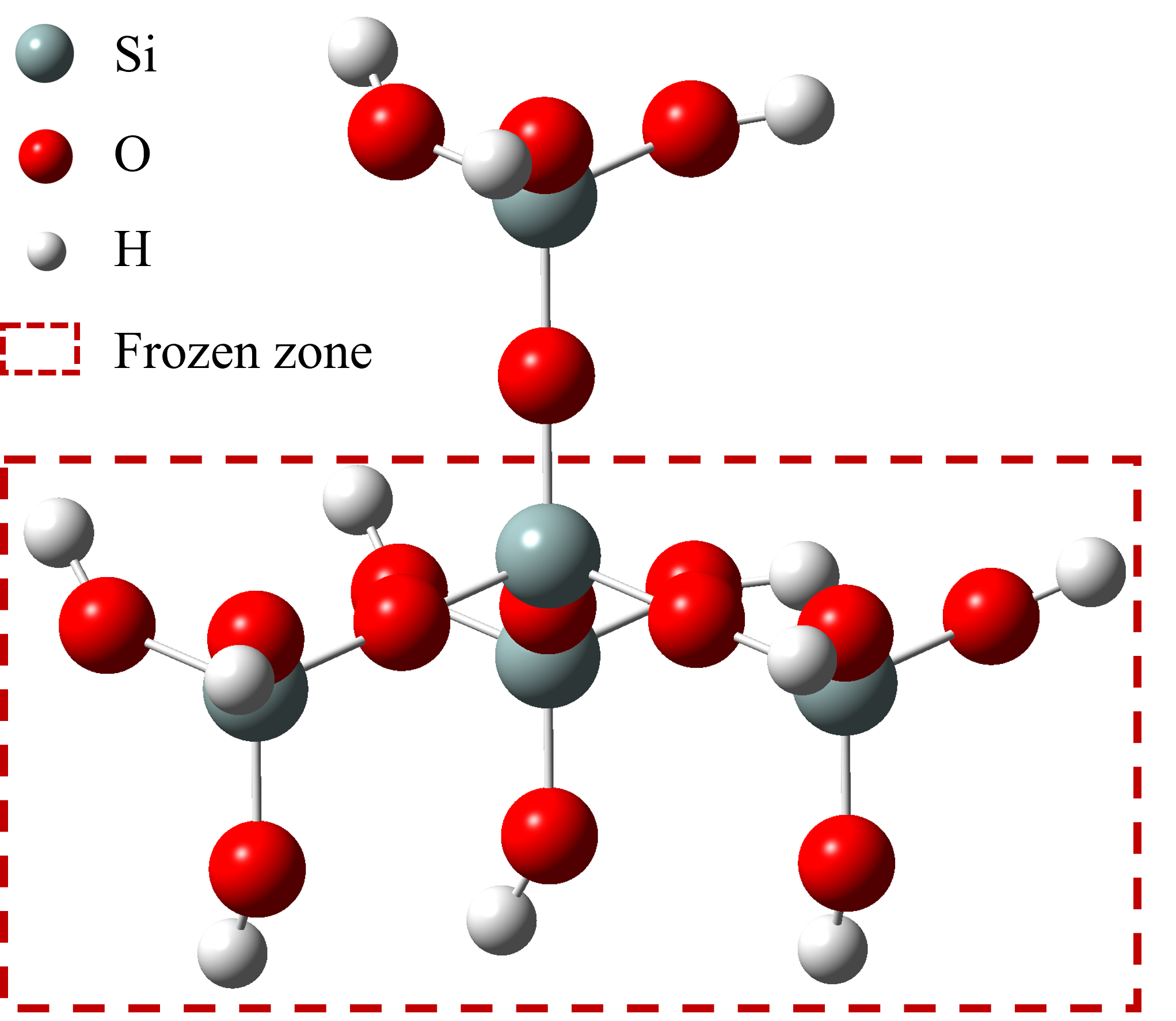

3.1. Modification of SiO2 Nanoparticles

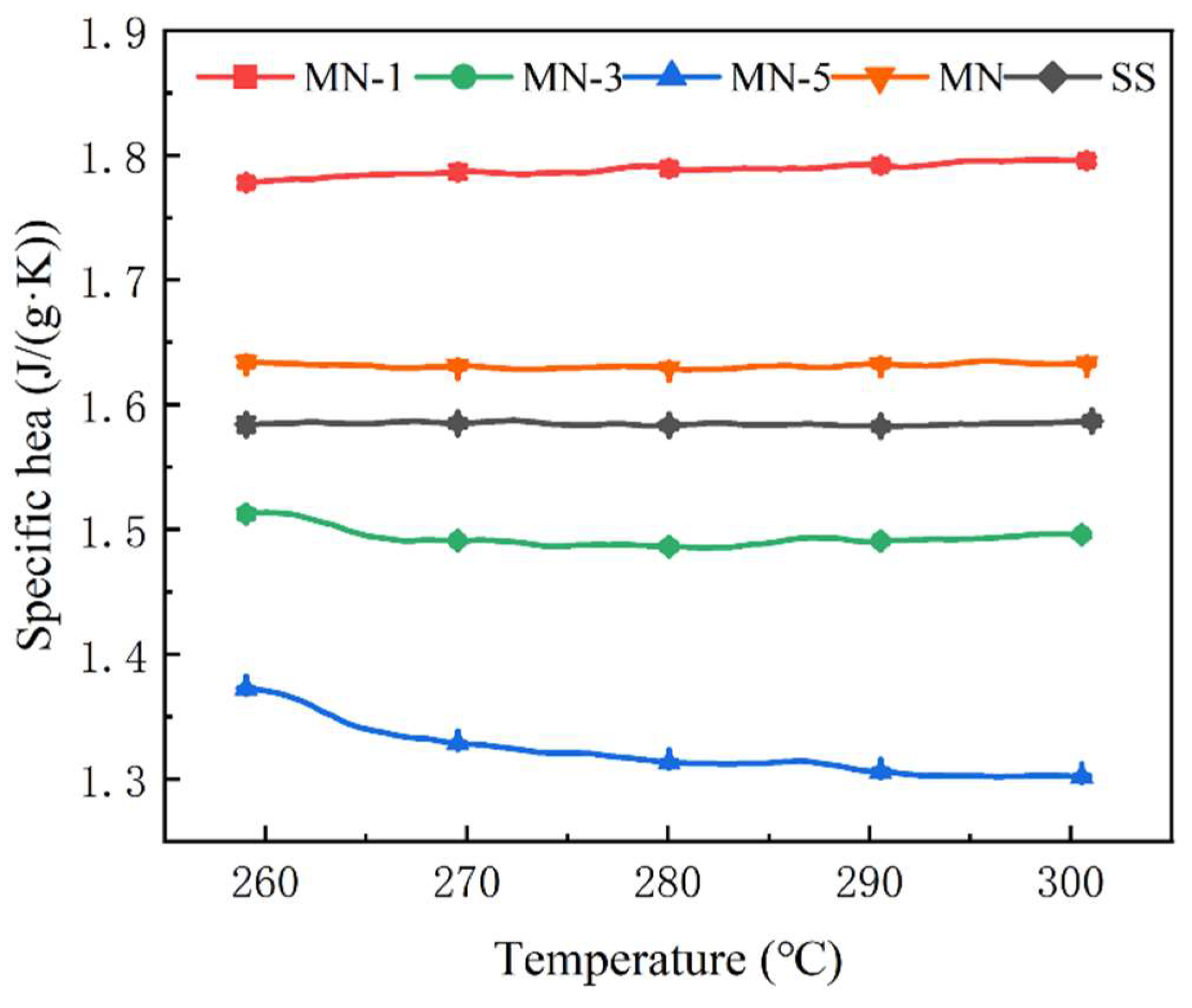

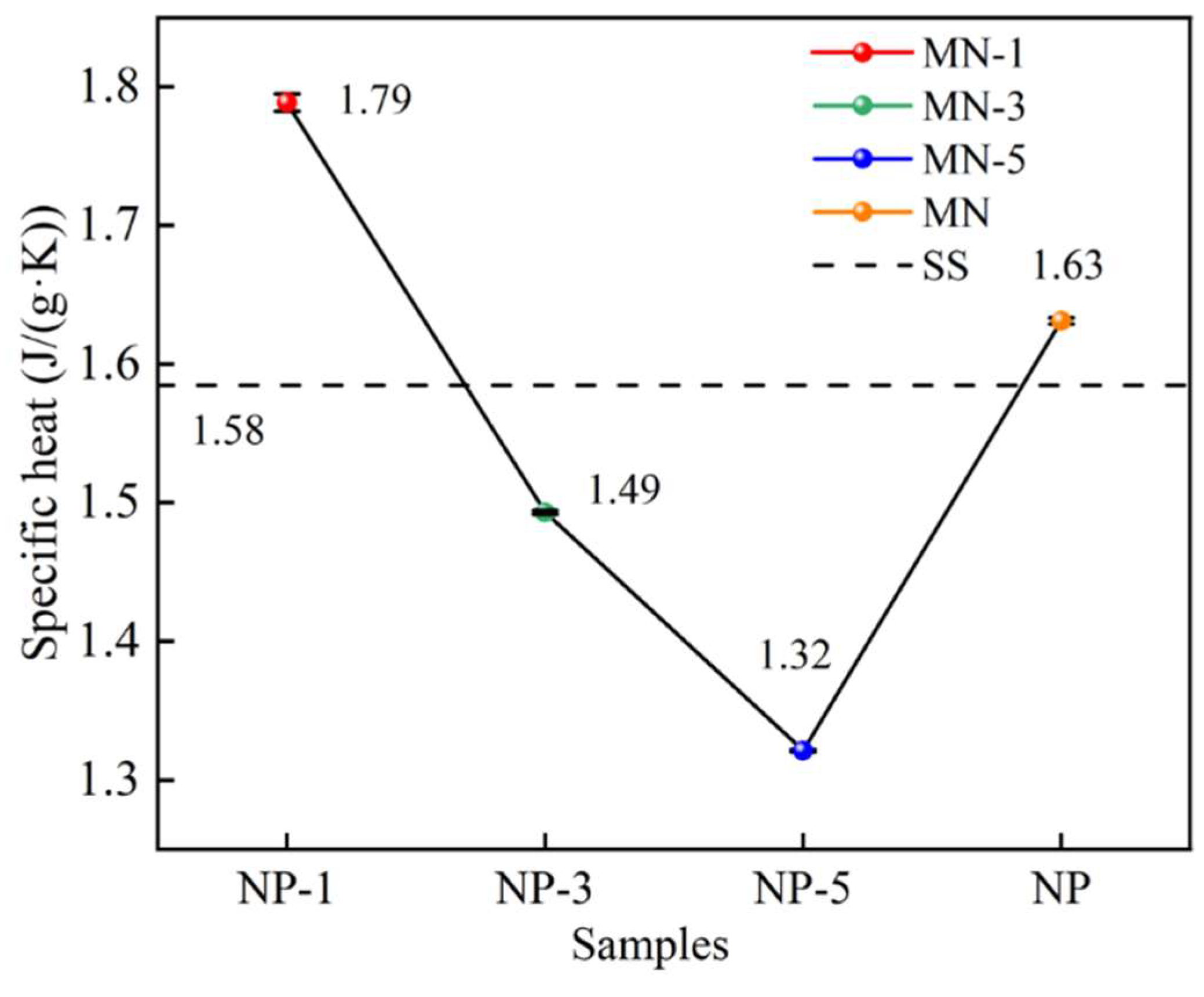

3.2. Specific Heat

3.3. Thermal Diffusion Coefficient

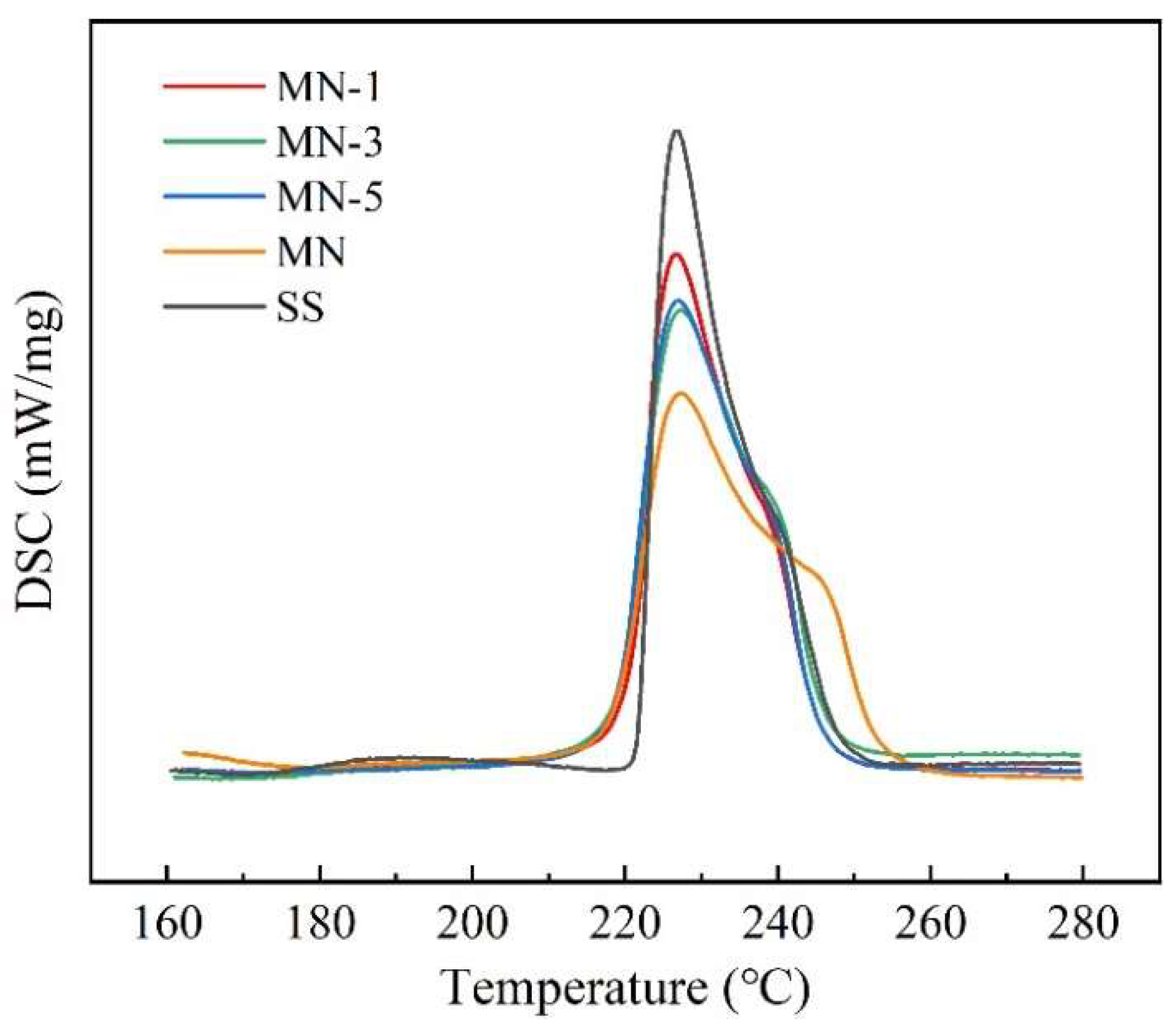

3.4. Melting Point and Latent Heat

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The surface charge of nano-SiO2 can be modified through acidification, and a higher acidity leads to a greater neutralization of their negative zeta potential. The potential of the unacidified nanoparticles in deionized water was −31.24 mV, whereas after treatment with hydrochloric acid at pH 1, the potential was reduced to −23.17 mV. The acidification process was found to induce changes in the surface elemental content and chemical bonds of the nanoparticles.

- (2)

- The specific heat of molten salt-nanoparticle composites can be affected by the microelectric field generated by charged nanoparticles. A specific heat capacity of 1.79 J/(g·K) was achieved for the molten salt when nanoparticles treated with HCl at pH = 1 were incorporated, representing a 13.3% enhancement compared to Solar Salt. However, it was also observed that the specific heat of Solar Salt was reduced to varying degrees by nanoparticles treated at pH = 3 and pH = 5. In this study, it is suggested that the effect of the nanoparticle charge on the spacing of the surrounding positive and negative ions may be an important factor contributing to this phenomenon of specific heat change.

- (3)

- The thermal diffusivity, melting point, and latent heat of the composite material are also influenced by the effect of nanoparticle surface charge on the separation between surrounding cations and anions. The underlying mechanisms are associated with the extent of ion aggregation, as well as the bonding energy and quantity of chemical bonds between cations and anions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, S.N.; Ma, N.L.; Chen, X.Y. Status quo and development trend of molten salt thermal storage technology based on photothermal energy. Xinjiang Oil Gas 2024, 20, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, M.; Liang, M.; Yan, T.; Zhao, D. Research progress on specific heat capacity improvement of molten salt nanofluids. Integr. Intell. Energy 2024, 46, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod, M.K.; Banerjee, J. Thermal stability of phase change materials used in latent heat energy storage systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, M.; Ji, C.; Xie, J. Performance comparison of CSP system with different heat transfer and storage fluids at multi-time scales by means of system advisor model. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 269, 112765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Cheng, J.; Jin, Y.; An, X. Evaluation of thermal physical properties of molten nitrate salts with low melting temperature. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 176, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, N.; Hernández, L.; Vela, A.; Mondragón, R. Influence of the production method on the thermophysical properties of high temperature molten salt-based nanofluids. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 302, 112570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayashankar, N.; González-Fernández, L.; Grosu, Y.; Zaki, A.; Igartua, J.M.; Faik, A. Shape effect of Al2O3 nanoparticles on the thermophysical properties and viscosity of molten salt nanofluids for TES application at CSP plants. Int. J. Thermophys. 2020, 169, 114942. [Google Scholar]

- Aljaerani, H.A.; Samykano, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Kadirgama, K.; George, M.; Saidur, R. Thermophysical properties enhancement and characterization of CuO nanoparticles enhanced HITEC molten salt for concentrated solar power applications. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 132, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaerani, H.A.; Samykano, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Said, Z.; Sudhakar, K.; Saidur, R. Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the thermal energy storage of HITEC salt for concentrated solar power applications. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y. Comprehensive thermal properties of molten salt nanocomposite materials base on mixed nitrate salts with SiO2/TiO2 nanoparticles for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svobodova-Sedlackova, A.; Barreneche, C.; Alonso, G.; Fernandez, A.I.; Gamallo, P. Effect of nanoparticles in molten salts—MD simulations and experimental study. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Banerjee, D. Enhancement of specific heat capacity of high-temperature silica-nanofluids synthesized in alkali chloride salt eutectics for solar thermal-energy storage applications. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 54, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Keblinski, P.; Phillpot, S.R.; Choi, S.U.; Eastman, J.A. Effect of liquid layering at the liquid-solid interface on thermal transport. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2004, 47, 4277–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Lasfargues, M.; Alexiadis, A.; Ding, Y.J.A.T.E. Simulation and experimental study of the specific heat capacity of molten salt based nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 111, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhai, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H. Mechanism of enhanced thermal conductivity of hybrid nanofluids by adjusting mixing ratio of nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 400, 124518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W. Molecular dynamics simulation study on the mechanism of nanoparticle dispersion stability with polymer and surfactant additives. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 298, 120425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Bao, G.; Lu, Y.; Gong, Y. Study on thermophysical properties improvement of ternary nitrate-carbonate molten salt by adding SiO2 nanoparticles for large-scale thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 292, 113819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xie, J. Enhanced heat transfer and thermal storage performance of molten K2CO3 by ZnO nanoparticles: A molecular dynamics study. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 407, 125203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithiyanantham, U.; Pradeep, N.; Reddy, K.S. Development and comparison of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and graphite nanoflakes dispersed solar salt: Structural formation and thermophysical properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 402, 124787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Cabedo, P.; Mondragon, R.; Hernandez, L.; Martinez-Cuenca, R.; Cabedo, L.; Julia, J.E. Increment of specific heat capacity of solar salt with SiO2 nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieruzzi, M.; Cerritelli, G.F.; Miliozzi, A.; Kenny, J.M. Effect of nanoparticles on heat capacity of nanofluids based on molten salts as PCM for thermal energy storage. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.T.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.C.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, H.L.G.A.; Nakatsuji, X.; et al. Gaussian 16; Revision C.01. Gaussian, Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2016. Available online: www.gaussian.com (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Koch, W.; Holthausen, M.C. A Chemist’s Guide to Density Functional Theory; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, E.; Dobson, J.; Petersilka, M. Density functional theory of time-dependent phenomena. Density Funct. Theory 1996, 2, 81–172. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, W.K.; Hertwig, H. On the parameterization of the local correlation functional. What is Becke-3-LYP. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 268, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, H.B. Optimization of equilibrium geometries and transition structures. J. Comput. Chem. 1982, 3, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Zhu, C.; Gu, M.; Xu, M.; He, W. Thermophysical properties enhancement of KNO3–NaNO3–NaNO2 mixed with SiO2/MgO nanoparticles. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2025, 10, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, O.; Wan, N.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, L.; Chen, T.; Liu, X. Effect of pH on the Dispersion Characteristics of Fumed Silica. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2011, 28, 1448–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K.; Deru, H.; Renqing, W. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganicand Coordination Compounds; Beijing Chemical Industry Press Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Nan, D.; Kaizhong, W. Study on the Preparation of Silica Aerogel via Ambient Pressure Drying Using Low-Cost Silica Sol. Rubber Plast. Resour. Util. 2024, 6, 1–6+14. [Google Scholar]

- COD Search Tool: Crystallographic Structure Search Interface. Available online: http://www.crystallography.net/cod/search.php (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Maity, N.; Barman, S.; Abou-Hamad, E.; D’Elia, V.; Basset, J.-M. Clean chlorination of silica surfaces by a single-site substitution approach. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 4301–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yit-Yian Lua, W.J.J.F.; Li, Y.; Lee, M.V.; Savage, P.B.; Asplund, M.C.; Linford, M.R. First reaction of a bare silicon surface with acid chlorides and a one step preparation of acid chloride terminated. ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2005, 21, 2094–2097. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Jug, K. The Formation of a Solid from the Reaction SiCl4(g) + O2(g) →SiO2(s) + 2 Cl2(g). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 6, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.C.; Huang, C.H. Specific heat capacity of molten salt-based alumina nanofluid. J. Mol. Liq. 2013, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudda, B.; Shin, D. Effect of nanoparticle dispersion on specific heat capacity of a binary nitrate salt eutectic for concentrated solar power applications. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2013, 69, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Jo, B. Understanding mechanism of enhanced specific heat of single molten salt-based nanofluids: Comparison with acid-modified salt. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 116561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, W.W.; Wang, C.G.; Zhu, Q.Z. Research on the effect of adding NaCl on the performance of KNO3–NaNO3 binary molten salt. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 148, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Li, S.; Hou, D.W. Influence of Nanomaterials onThermal Performance of Molten Salt. Gas Heat 2024, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Raw Material | Melting Point (°C) | Density (g/cm3) | Latent Heat (J/g) | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaNO3 | 310 | 2.26 | 173 | ≥99.0 |

| KNO3 | 337 | 2.11 | 115 | ≥99.0 |

| Element Types | NP-1 | NP-3 | NP-5 | NP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | 68.90 | 70.91 | 70.83 | 71.58 |

| Si | 31.00 | 28.78 | 28.94 | 28.30 |

| Cl | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.11 |

| Molecule | Si-O (1#) | O (1#)-H (1#) | H (1#)-Cl | Cl-Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 1.66 | 1.77 | 1.32 | 4.08 |

| TS | 1.86 | 0.99 | 2.12 | 2.51 |

| P | 6.04 | 0.96 | 5.53 | 2.06 |

| Samples | MN-1 | MN-3 | MN-5 | MN | SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal diffusivity (mm2/s) | 0.940 (±0.003) a | 0.917 (±0.002) a | 0.875 (±0.000) a | 0.845 (±0.000) a | 0.821 (±0.002) a |

| Samples | MN-1 | MN-3 | MN-5 | MN | SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting point (°C) | 220.6 (±0.2) a | 219.1 (±0.1) a | 219.3 (±0.1) a | 218.9 (±0.1) a | 221.9 (±0.1) a |

| Latent heat (J/g) | 106.0 (±0.2) a | 105.8 (±0.1) a | 105.1 (±0.1) a | 102.8 (±0.2) a | 113.7 (±0.3) a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, M.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, C.; Li, P.; Han, W. The Regulating Role of Nano-SiO2 Potential in the Thermophysical Properties of NaNO3-KNO3. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241854

Gu M, Zhang D, Zhu C, Li P, Han W. The Regulating Role of Nano-SiO2 Potential in the Thermophysical Properties of NaNO3-KNO3. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241854

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Manting, Dan Zhang, Chuang Zhu, Panfeng Li, and Wenxin Han. 2025. "The Regulating Role of Nano-SiO2 Potential in the Thermophysical Properties of NaNO3-KNO3" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241854

APA StyleGu, M., Zhang, D., Zhu, C., Li, P., & Han, W. (2025). The Regulating Role of Nano-SiO2 Potential in the Thermophysical Properties of NaNO3-KNO3. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241854