Effect of Anodization Temperature on the Morphology and Structure of Porous Alumina Formed in Selenic Acid Electrolyte

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

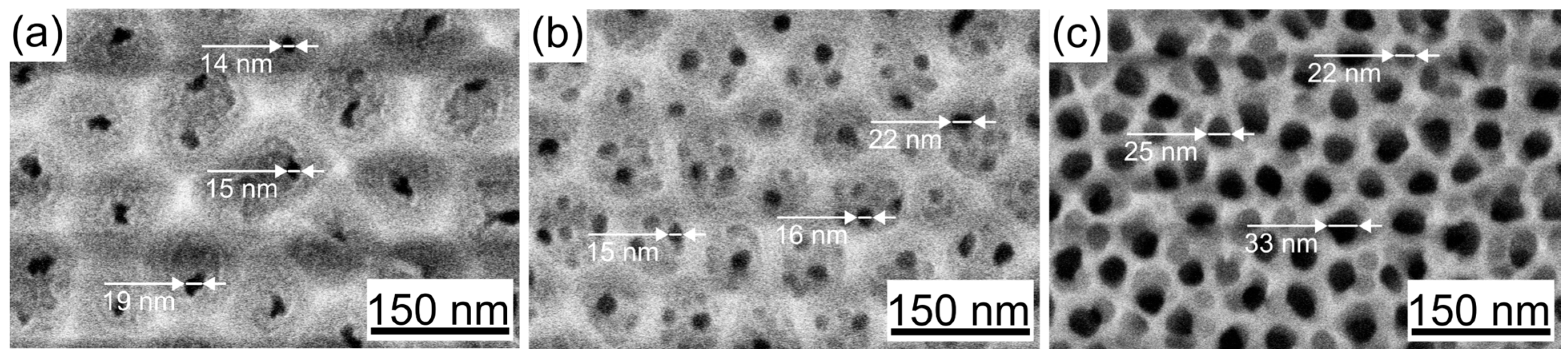

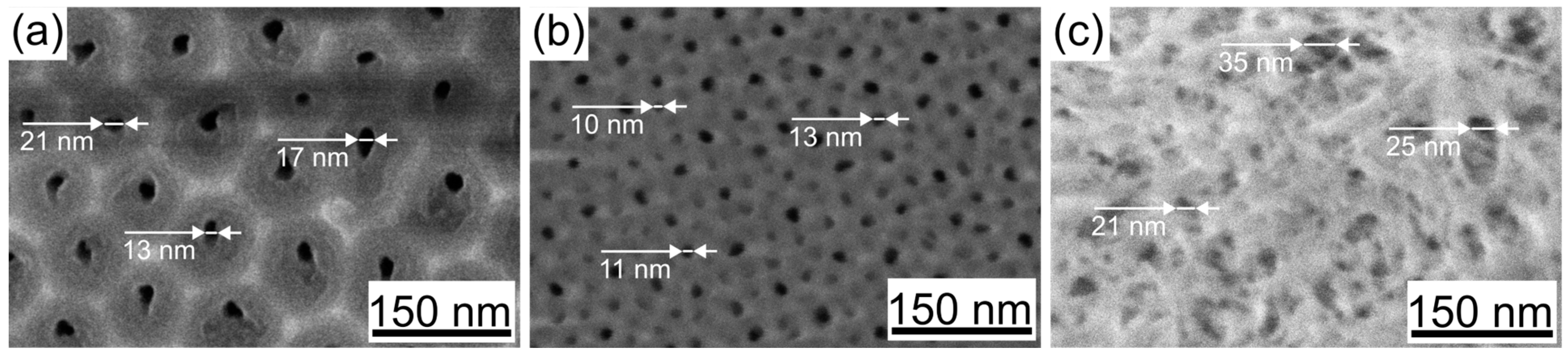

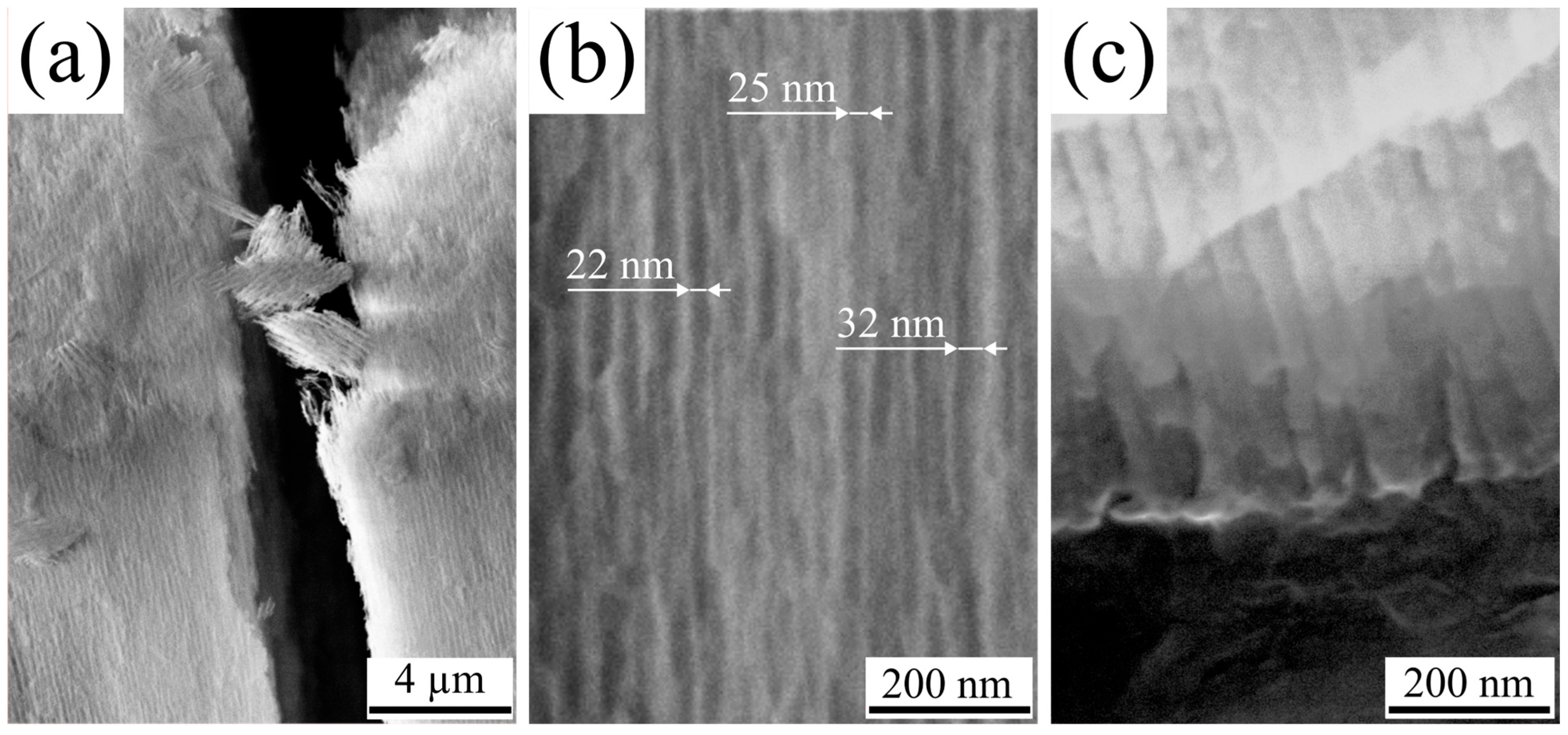

3.1. Morphology

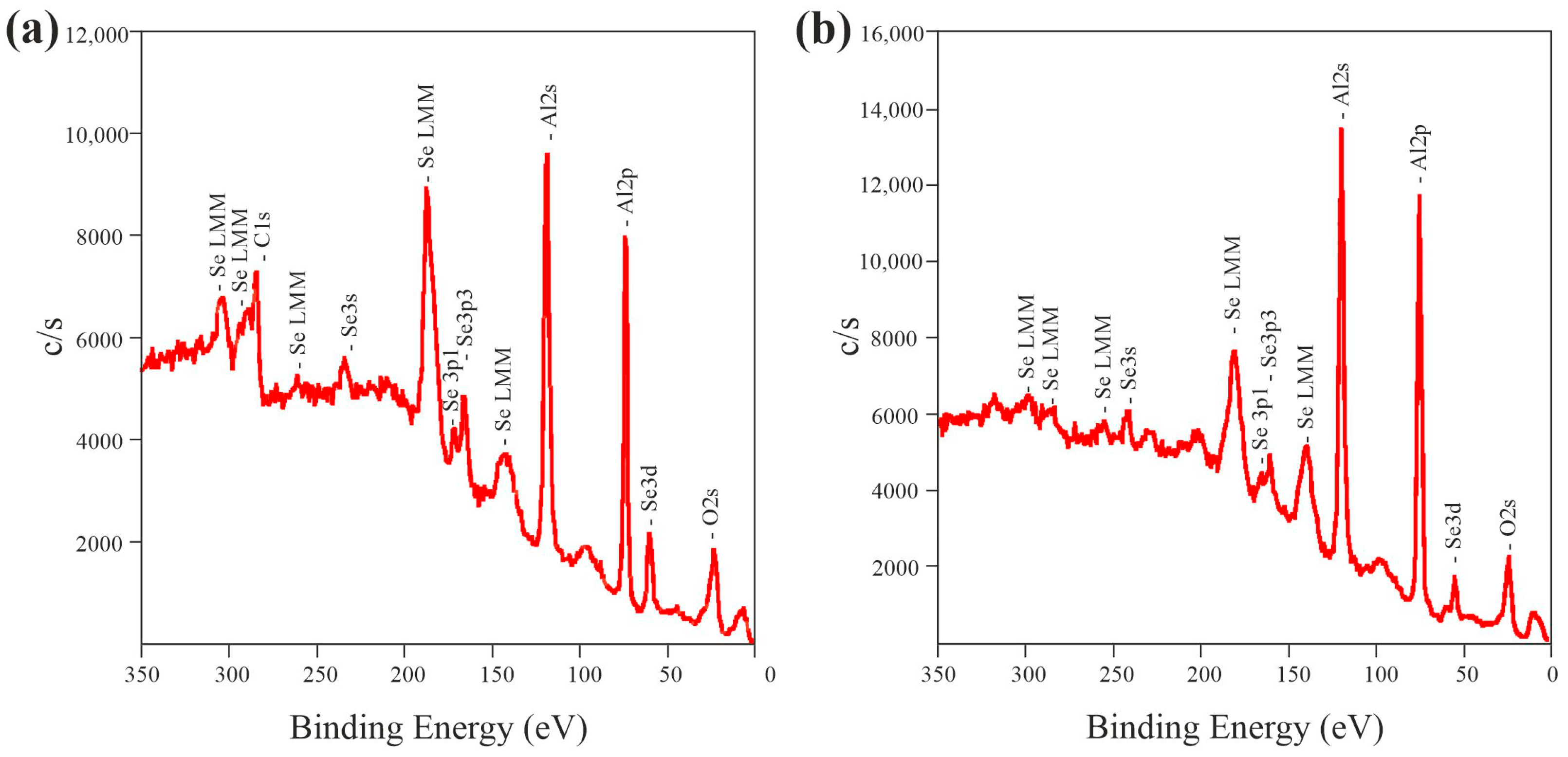

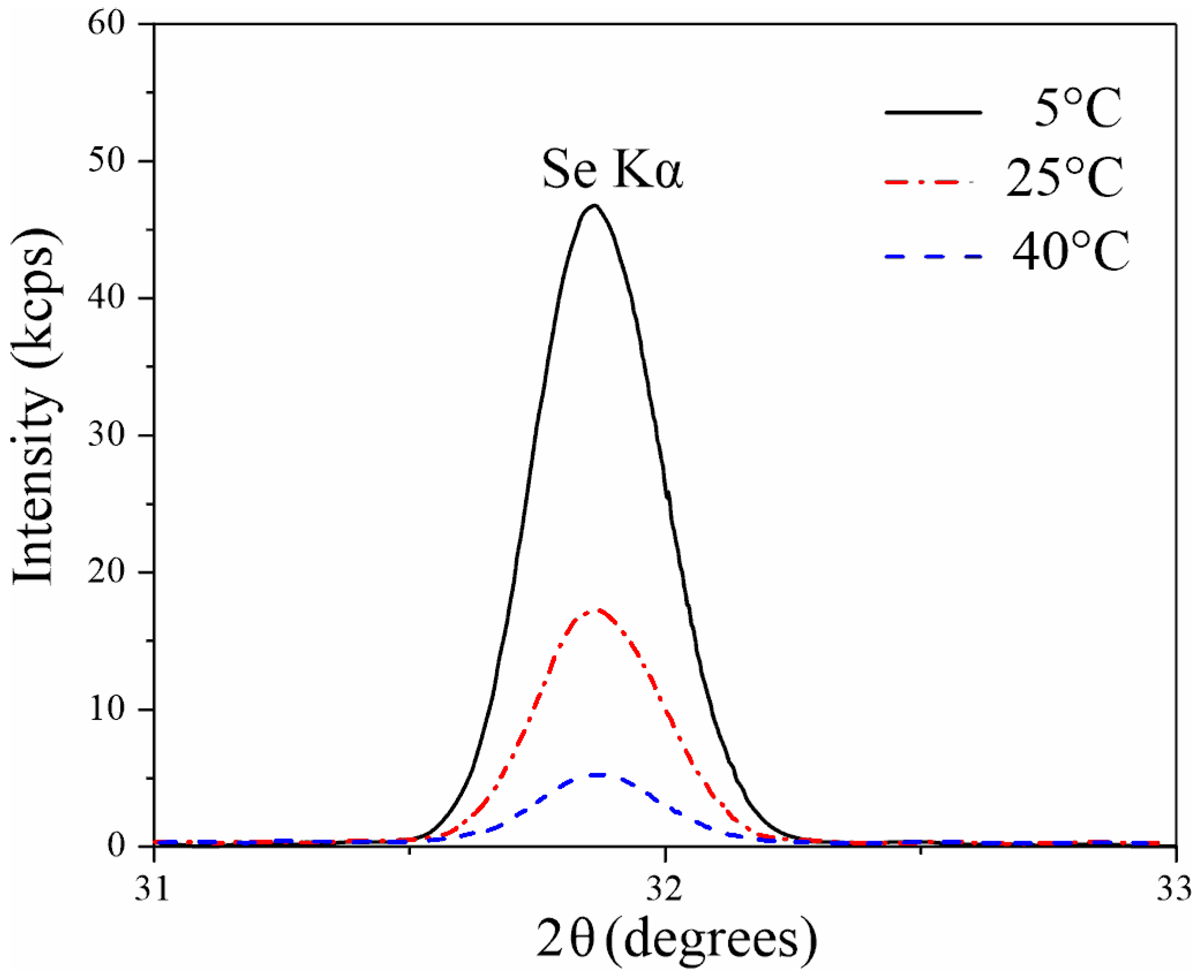

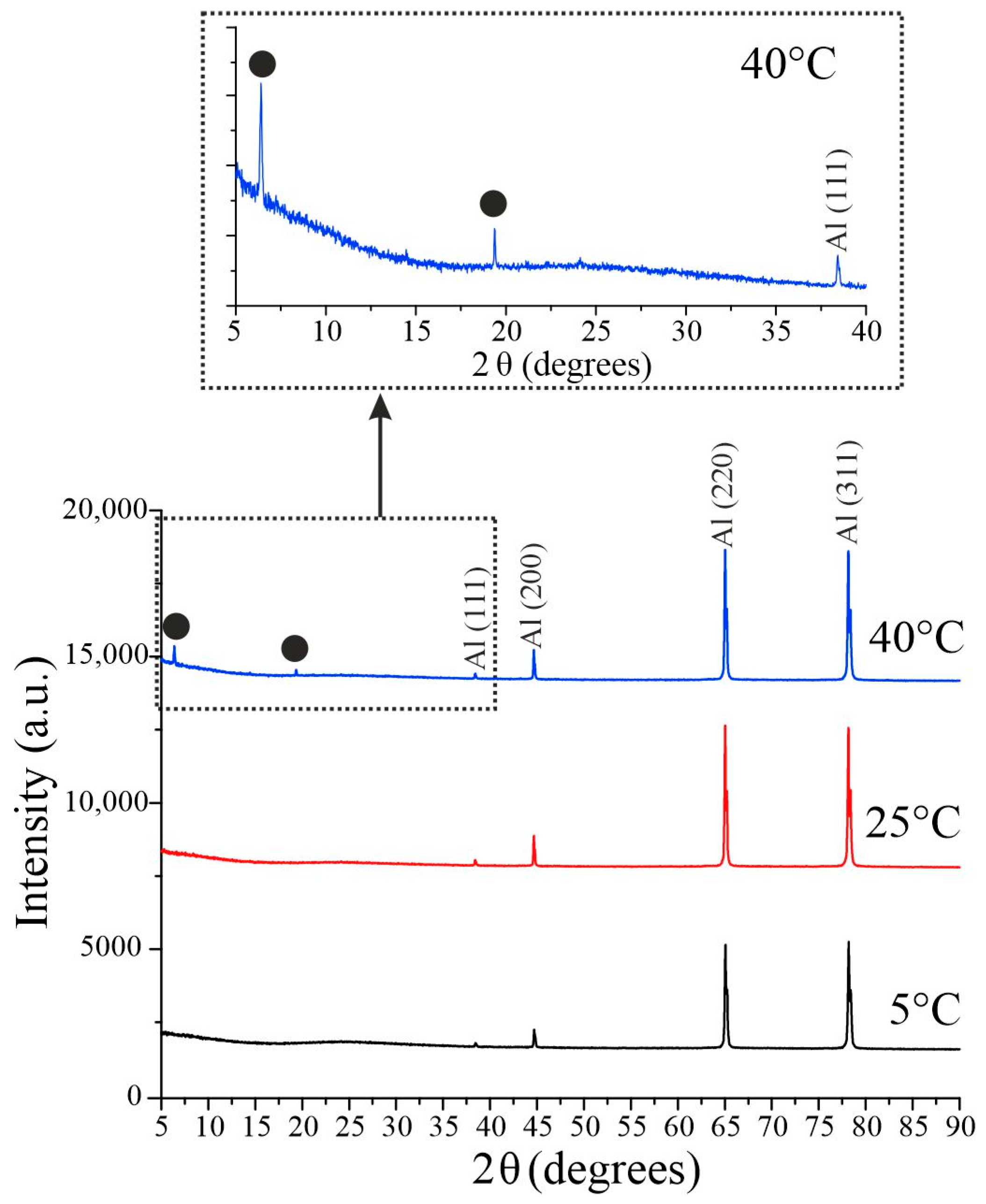

3.2. Chemical and Crystal Structure

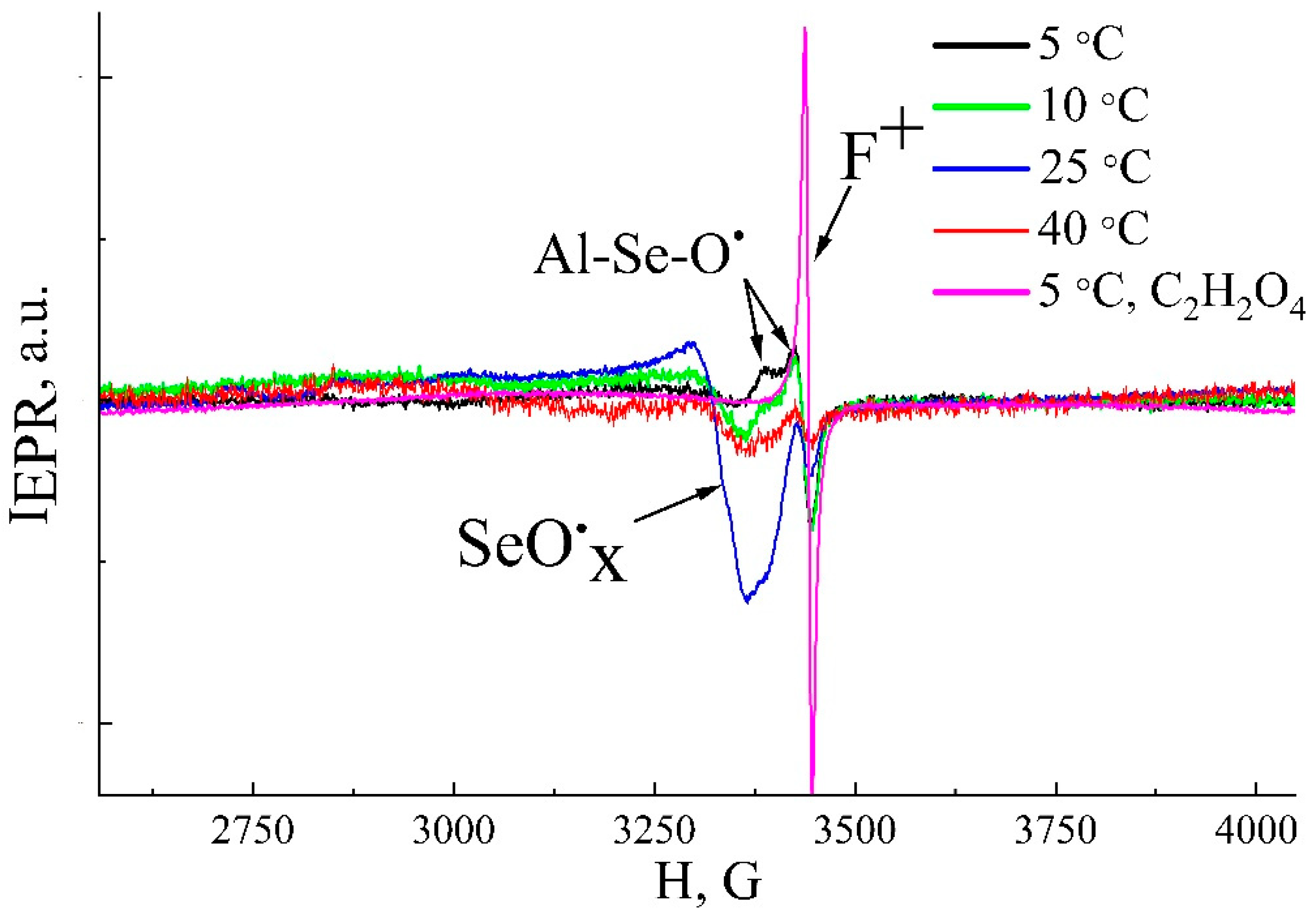

3.3. Luminescent Properties and Paramagnetic Centers

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santos, A.; Kumeria, T.; Losic, D. Nanoporous anodic aluminum oxide for chemical sensing and biosensors. Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 44, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elnaiem, A.M.; Mohamed, Z.A.; Soliman, S.E.; Almokhtar, M. Synthesis, characterization, and optical sensing of hydrophilic anodic alumina films. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadykov, A.I.; Kushnir, S.E.; Roslyakov, I.V.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Napolskii, K.S. Selenic Acid Anodizing of Aluminium for Preparation of 1D Photonic Crystals. Electrochem. Commun. 2019, 100, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Meng, G.; Han, F.; Li, X.; Chen, B.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Chu, Z.; Kong, M.; Huang, Q. Nanocontainers made of various materials with tunable shape and size. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, L.N.; Vollebregt, S. Overview of Engineering Carbon Nanomaterials Such As Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Carbon Nanofibers (CNFs), Graphene and Nanodiamonds and Other Carbon Allotropes inside Porous Anodic Alumina (PAA). Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzózka, A.; Brudzisz, A.; Hnida, K.; Sulka, G.D. Chemical and Structural Modifications of Nanoporous Alumina and Its Optical Properties. In Electrochemically Engineered Nanoporous Materials, 1st ed.; Losic, D., Santos, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 220, pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinaga, O.; Kikuchi, T.; Natsui, S.; Suzuki, R.O. Rapid fabrication of self-ordered porous alumina with 10-/sub-10-nm-scale nanostructures by selenic acid anodizing. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarkina, Y.; Gavrilov, S.; Terryn, H.; Petrova, M.; Ustarroz, J. Investigation of the Ordering of Porous Anodic Alumina Formed by Anodization of Aluminum in Selenic Acid. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, E166–E172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarkina, Y.; Kamnev, K.; Dronov, A.; Dudin, A.; Pavlov, A.; Gavrilov, S. Features of Porous Anodic Alumina Growth in Galvanostatic Regime in Selenic Acid Based Electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 231, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, M.; Kashi, M.A.; Noormohammadi, M.; Ramazani, A. Small-diameter magnetic and metallic nanowire arrays grown in anodic porous alumina templates anodized in selenic acid. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2021, 127, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnev, K.; Bendova, M.; Fohlerova, Z.; Fialova, T.; Martyniuk, O.; Prasek, J.; Cihalova, K.; Mozalev, A. Arrays of ultra-thin selenium-doped zirconium-anodic-oxide nanorods as potential antibacterial coatings. Mater. Chem. Front. 2025, 9, 866–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeeva, E.O.; Roslyakov, I.V.; Napolskii, K.S. Aluminium anodizing in selenic acid: Electrochemical behaviour, porous structure, and ordering regimes. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 307, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiya, S.; Kikuchi, T.; Natsui, S.; Suzuki, R.O. Optimum Exploration for the Self-Ordering of Anodic Porous Alumina Formed via Selenic Acid Anodizing. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, E244–E250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.; O’Sullivan, J.P. The anodizing of aluminium in sulphate solutions. Electrochim. Acta 1970, 15, 1865–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kytina, E.V.; Konstantinova, E.A.; Pavlikov, A.V.; Nazarkina, Y.V.; Dronova, D.A. Influence of Synthesis Conditions on the Photoluminescence Properties and Paramagnetic Centers of Porous Alumina Formed in Sulfuric Acid. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2025, 89, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Ng, K.Y.; Ngan, A.H.W. Quantitative characterization of acid concentration and temperature dependent self-ordering conditions of anodic porous alumina. AIP Adv. 2011, 1, 042113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępniowski, W.J.; Bojar, Z. Synthesis of anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) at relatively high temperatures. Study of the influence of anodization conditions on the alumina structural features. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 206, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.M.J.; Butt, M.Z. First-Step Anodization of Commercial Aluminum in Oxalic Acid: Activation Energy of Rate Process and Structural Features of Porous Alumina and of Aluminum Substrate as a Function of Temperature. J. Chem. Soc. Pak 2018, 40, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Leontiev, A.P.; Roslyakov, I.V.; Napolskii, K.S. Complex Influence of Temperature on Oxalic Acid Anodizing of Aluminium. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 319, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadykov, A.I.; Leontev, A.P.; Kushnir, S.E.; Napolskii, K.S. Kinetics of the Formation and Dissolution of Anodic Aluminum Oxide in Electrolytes Based on Sulfuric and Selenic Acids. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 66, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnev, K.; Bendova, M.; Pytlicek, Z.; Prasek, J.; Kejík, L.; Güell, F.; Llobet, E.; Mozalev, A. Se-doped Nb2O5–Al2O3 composite-ceramic nanoarrays via the anodizing of Al/Nb bilayer in selenic acid. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 34712–34725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Badan, J.A.; Gilles, M.; Cortes, A.; Riveros, G.; Ramirez, D.; Gomez, H.; Quagliata, E.; Dalchiele, E.A.; Marotti, R.E. Optical properties of nanoporous Al2O3 obtained by aluminum anodization. Phys. Status Solidi (c) 2007, 4, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek, E.; Włodarski, M.; Norek, M. Fabrication of porous anodic alumina (PAA) by high-temperature pulse-anodization: Tuning the optical characteristics of PAA-based DBR in the NIR-MIR region. Materials 2020, 13, 5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kytina, E.V.; Konstantinova, E.A.; Pavlikov, A.V.; Nazarkina, Y.V. Effect of Synthesis Parameters on Photoluminescence of Dyes in Pores of Anodic Aluminum Oxide. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 19, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarkina, Y.; Kamnev, K.; Polokhin, A. The Effect of Annealing on the Raman Spectra of Porous Anodic Alumina Films Formed in Different Electrolytes. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Russia Section Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering Conference, ElConRus 2017, St. Petersburg, Russia, 31 January–2 February 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1409–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarkina, Y.; Gavrilov, S.A.; Polohin, A.A.; Gromov, D.; Shaman, Y.P. Application of porous alumina formed in selenic acid solution for nanostructures investigation via Raman spectroscopy. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2016, 10224, 102240J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.S.; Wu, X.L.; Mei, Y.F.; Shao, X.F.; Siu, G.G. Strong blue emission from anodic alumina membranes with ordered nanopore array. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Huang, C.P.; Chao, C.G.; Chen, T.M. The investigation of photoluminescence centers in porous alumina membranes. Appl. Phys. A 2006, 84, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staninski, K.; Kaczmarek, M. Afterglow luminescence phenomena in the porous anodic alumina. Opt. Mater. 2021, 121, 111615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Saito, M.; Ishiguro, M.; Asoh, H. Controlling Factor of Self-Ordering of Anodic Porous Alumina. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, B473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwirn, K.; Lee, W.; Hillebrand, R.; Steinhart, M.; Nielsch, K.; Gösele, U. Self-Ordered Anodic Aluminum Oxide Formed by H2SO4 Hard Anodization. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patermarakis, G. Thorough electrochemical kinetic and energy balance models clarifying the mechanisms of normal and abnormal growth of porous anodic alumina films. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2014, 730, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Hasegwa, F.; Ono, S. Self-Ordering of Cell Arrangement of Anodic Porous Alumina Formed in Sulfuric Acid Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, L127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępniowski, W.J.; Zasada, D.; Bojar, Z. First step of anodization influences the final nanopore arrangement in anodized alumina. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 206, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.E.; Furneaux, R.C.; Wood, G.C. Nucleation and growth of porous anodic films on Aluminium. Nature 1978, 272, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coz, F.; Arurault, L.; Datas, L. Chemical analysis of a single basic cell of porous anodic aluminium oxide templates. Mater. Charact. 2010, 61, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Ling, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, Y. A simple method for fabrication of highly ordered porous α-alumina ceramic membranes. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 7445–7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MyScope Training. Available online: https://www.myscope.training (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Parkhutik, V.P.; Belov, V.T.; Chernyckh, M.A. Study of aluminium anodization in sulphuric and chromic acid solutions—II. Oxide morphology and structure. Electrochim. Acta 1990, 35, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.G.; Singh, A.K.; Mandal, K. Structure dependent photoluminescence of nanoporous amorphous anodic aluminium oxide membranes: Role of F+ center defects. J. Lumin. 2013, 134, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorin, A.I. Electron Spin Resonance of Nanostructured Oxide. In Semiconductors: Chemical Physics of Nanostructured Semiconductors; Kokorin, A.I., Bahnemann, D.W., Eds.; Chapter 8; VSP Publishing: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 203–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, P.W.; Symons, M.C.R. The Structure of Inorganic Radicals: An Application of Electron Spin Resonance to the Study of Molecular Structure; Elsevier Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1967; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Pore Diameter, nm | Cell Diameter, nm | Porosity (SEM + Fiji), % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 M-5 °C-5 mA/cm2 | 15 ± 6 | 114 ± 10 | 1.5 |

| 0.5 M-25 °C-5 mA/cm2 | 16 ± 9 | 101 ± 8 | 7.5 |

| 0.5 M-40 °C-5 mA/cm2 | 25 ± 6 | 58 ± 6 | 16.5 |

| 1.5 M-5 °C-15 mA/cm2 | 17 ± 4 | 84 ± 7 | 2.0 |

| 1.5 M-25 °C-15 mA/cm2 | 11 ± 4 | 52 ± 5 | 4.2 |

| 1.5 M-40 °C-15 mA/cm2 * | 25 ± 10 | 37 ± 10 | 45.5 |

| Sample | Ion-Beam Etching | C | O | Al | Se | Se/Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 M-5 °C-15 mA/cm2 | - | 10.2 | 60.4 | 27.4 | 2.0 | 0.07 |

| 10 min | - | 60.4 | 38.2 | 1.4 | 0.04 | |

| 1.5 M-25 °C-15 mA/cm2 | - | 5.1 | 62.3 | 30.2 | 1.8 | 0.06 |

| 10 min | - | 59.7 | 39.1 | 1.2 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazarkina, Y.V.; Zaitsev, V.B.; Dronova, D.A.; Dronov, A.A.; Tsiniaikin, I.I.; Butmanov, D.D.; Savchuk, T.P.; Kytina, E.V.; Konstantinova, E.A.; Marikutsa, A.V. Effect of Anodization Temperature on the Morphology and Structure of Porous Alumina Formed in Selenic Acid Electrolyte. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241855

Nazarkina YV, Zaitsev VB, Dronova DA, Dronov AA, Tsiniaikin II, Butmanov DD, Savchuk TP, Kytina EV, Konstantinova EA, Marikutsa AV. Effect of Anodization Temperature on the Morphology and Structure of Porous Alumina Formed in Selenic Acid Electrolyte. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241855

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazarkina, Yulia V., Vladimir B. Zaitsev, Daria A. Dronova, Alexey A. Dronov, Ilia I. Tsiniaikin, Danil D. Butmanov, Timofey P. Savchuk, Ekaterina V. Kytina, Elizaveta A. Konstantinova, and Artem V. Marikutsa. 2025. "Effect of Anodization Temperature on the Morphology and Structure of Porous Alumina Formed in Selenic Acid Electrolyte" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241855

APA StyleNazarkina, Y. V., Zaitsev, V. B., Dronova, D. A., Dronov, A. A., Tsiniaikin, I. I., Butmanov, D. D., Savchuk, T. P., Kytina, E. V., Konstantinova, E. A., & Marikutsa, A. V. (2025). Effect of Anodization Temperature on the Morphology and Structure of Porous Alumina Formed in Selenic Acid Electrolyte. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241855