First-Principles Investigation of Zr-Based Equiatomic Quaternary Heusler Compounds Under Hydrostatic Pressure for Spintronics Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Structural Stability

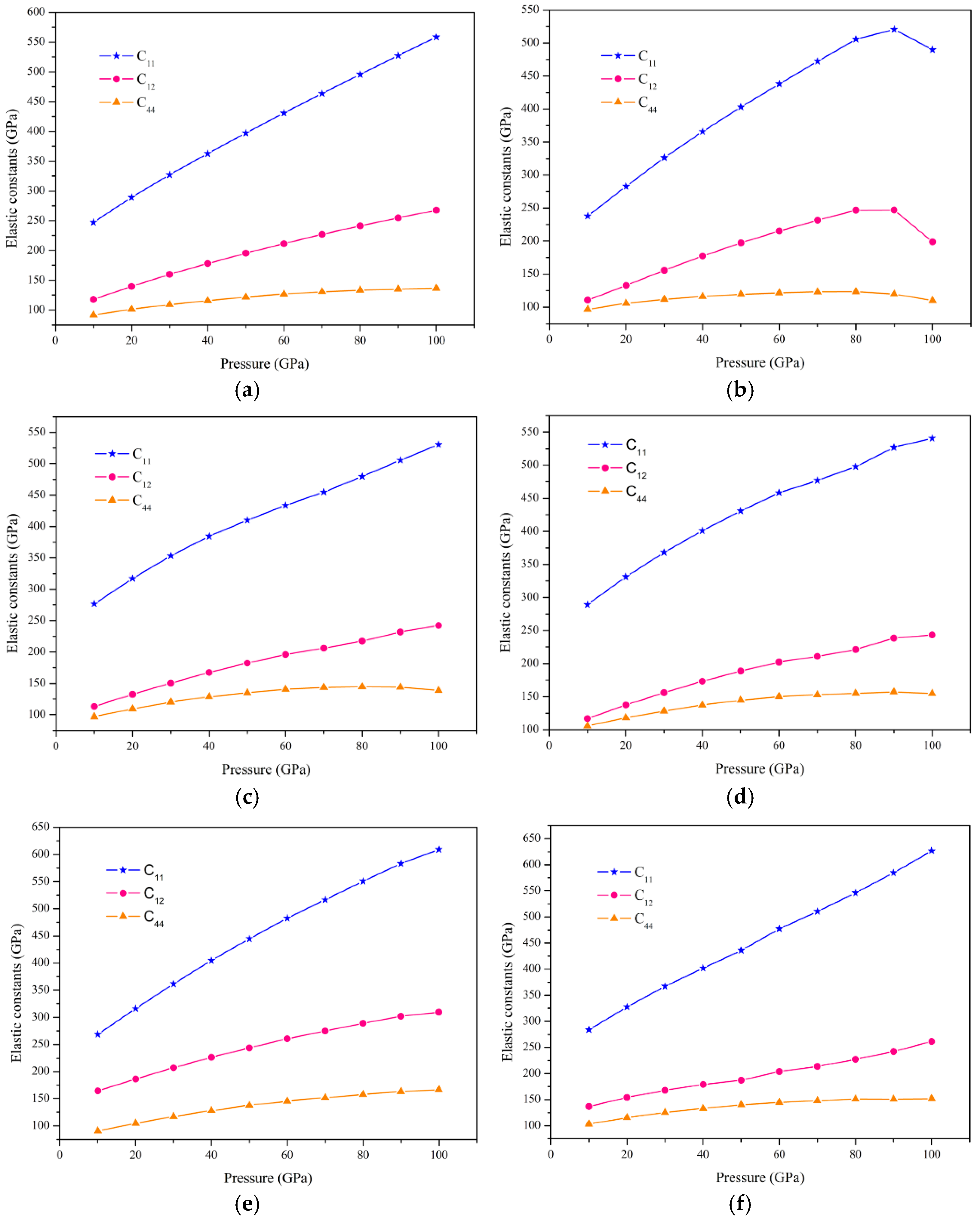

3.2. Elastic and Mechanical Properties

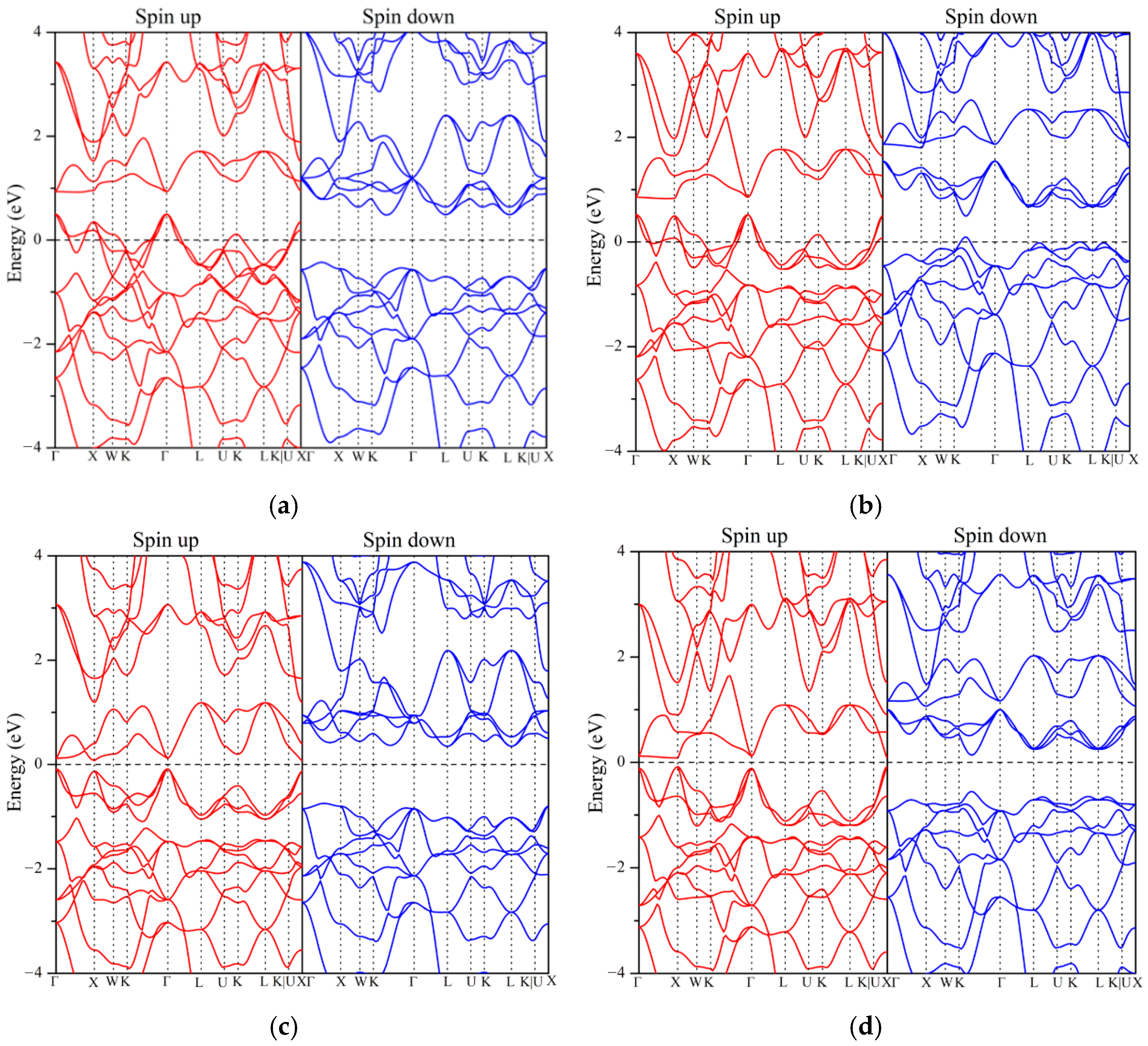

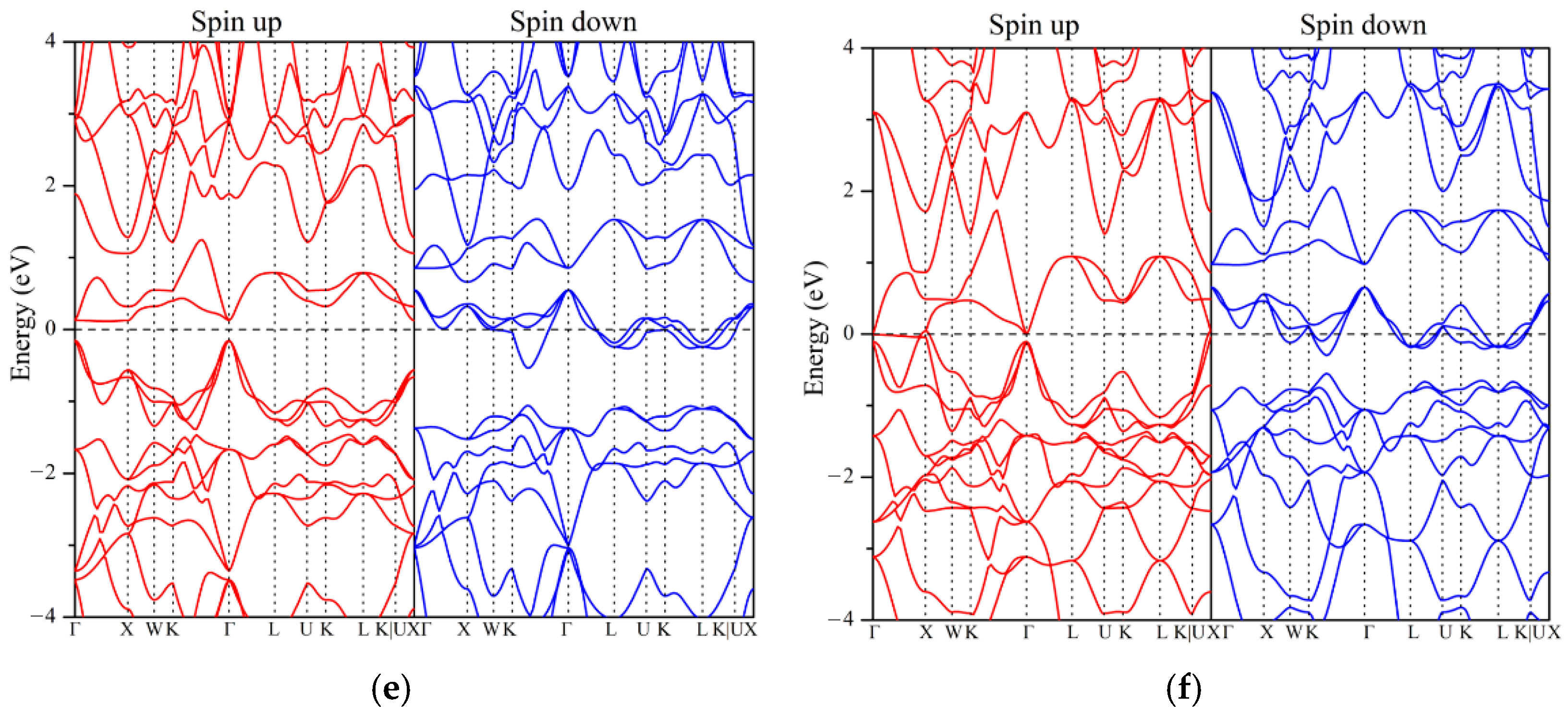

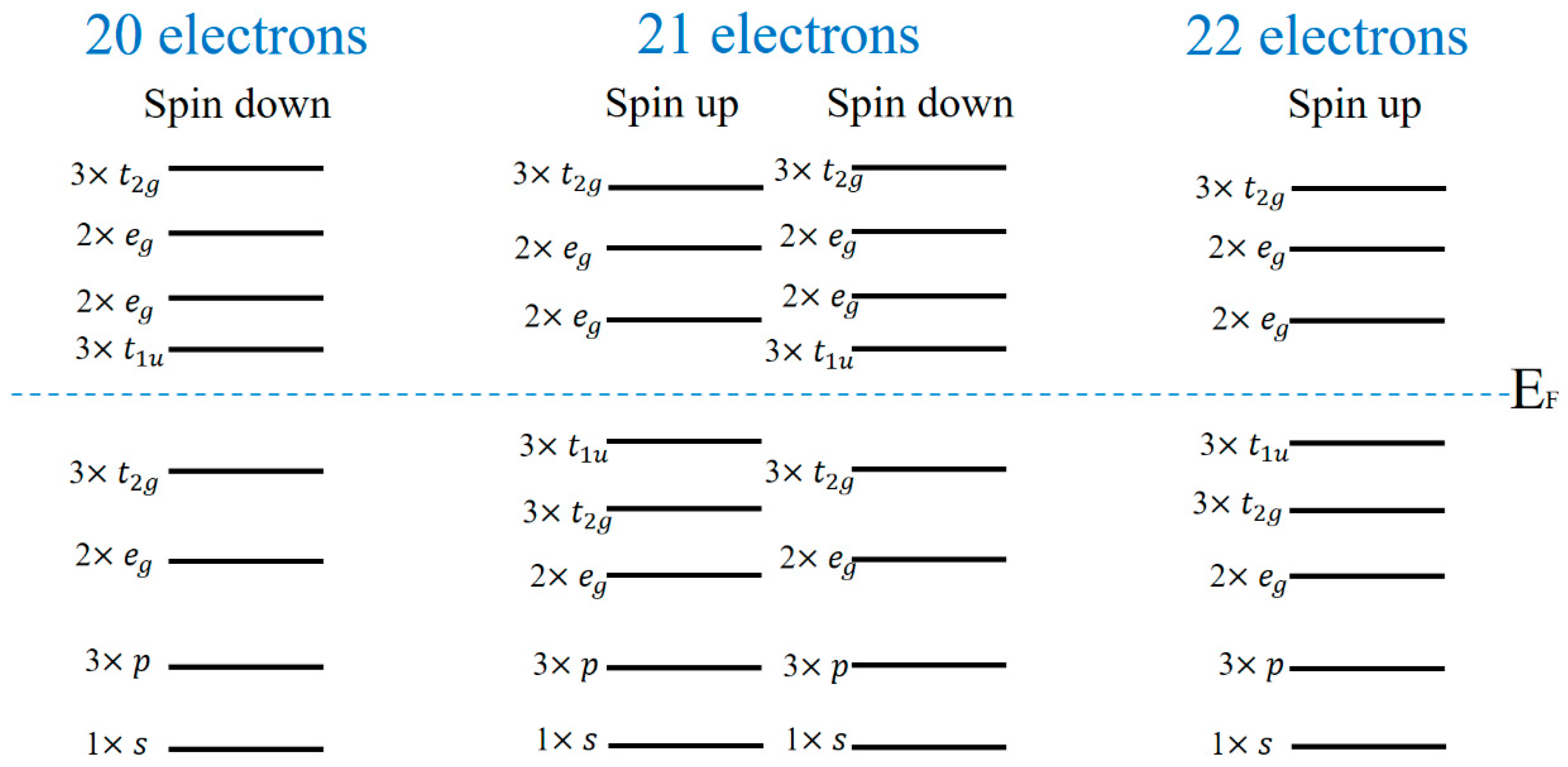

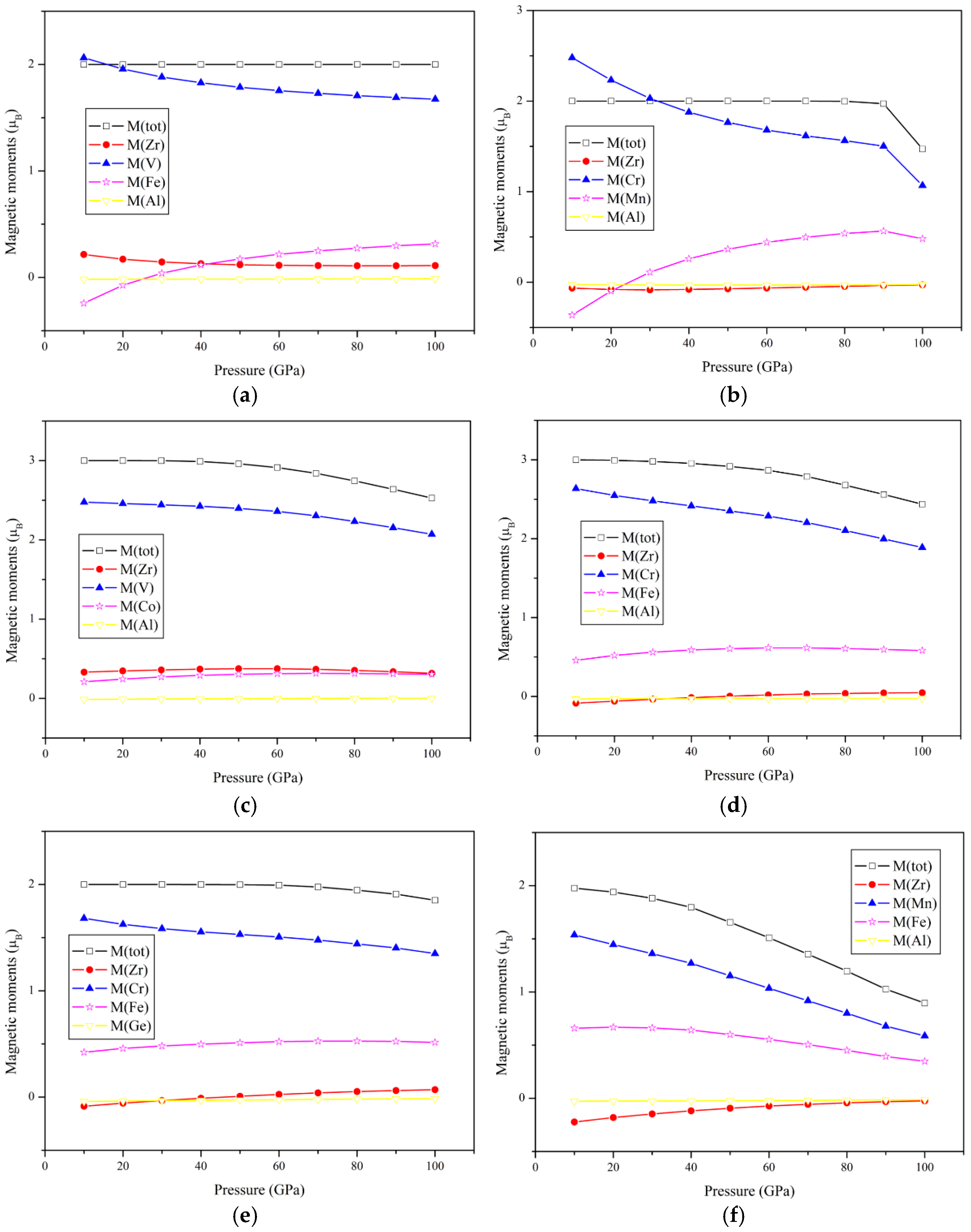

3.3. Electronic Structure and Magnetic Properties

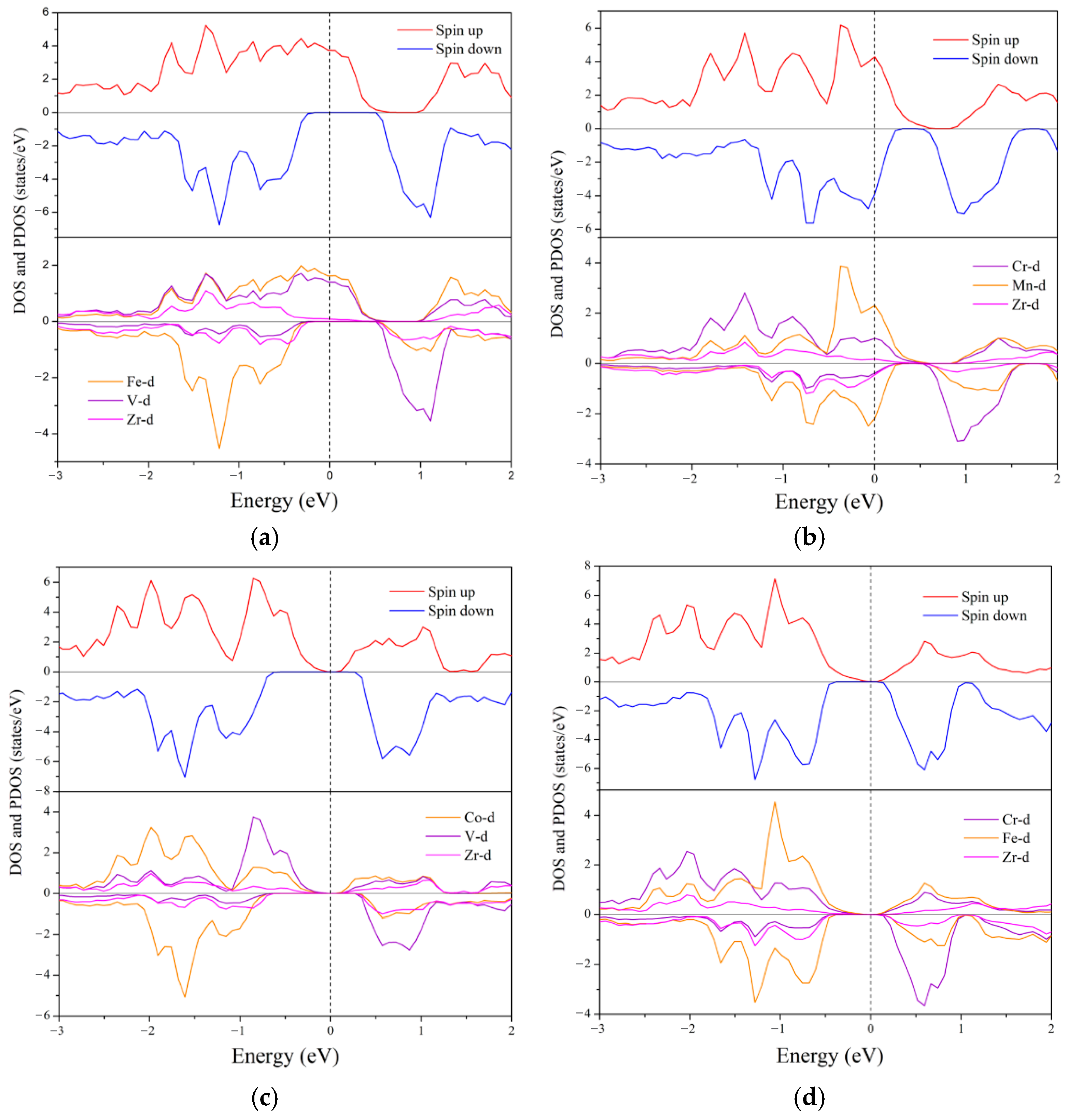

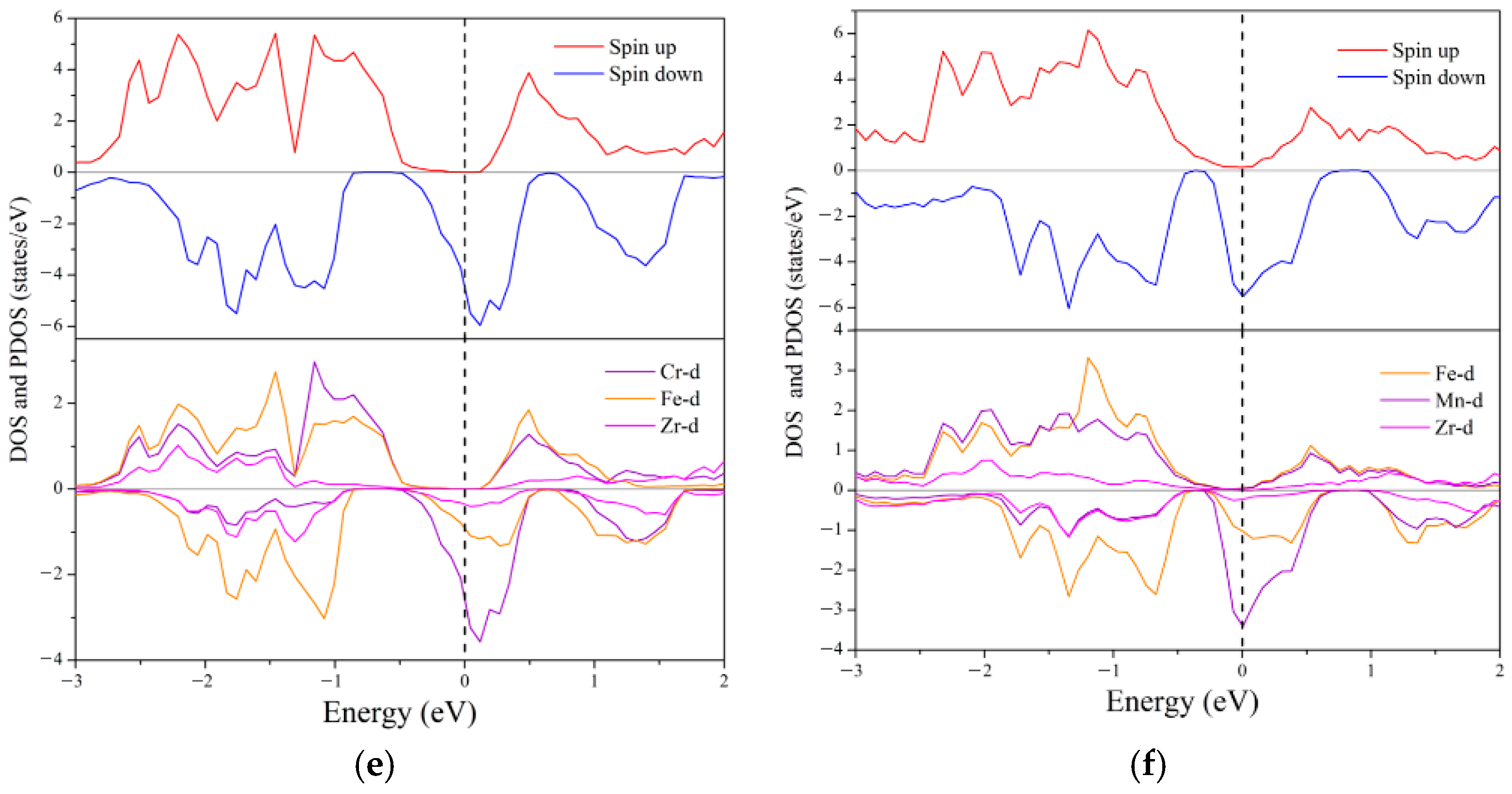

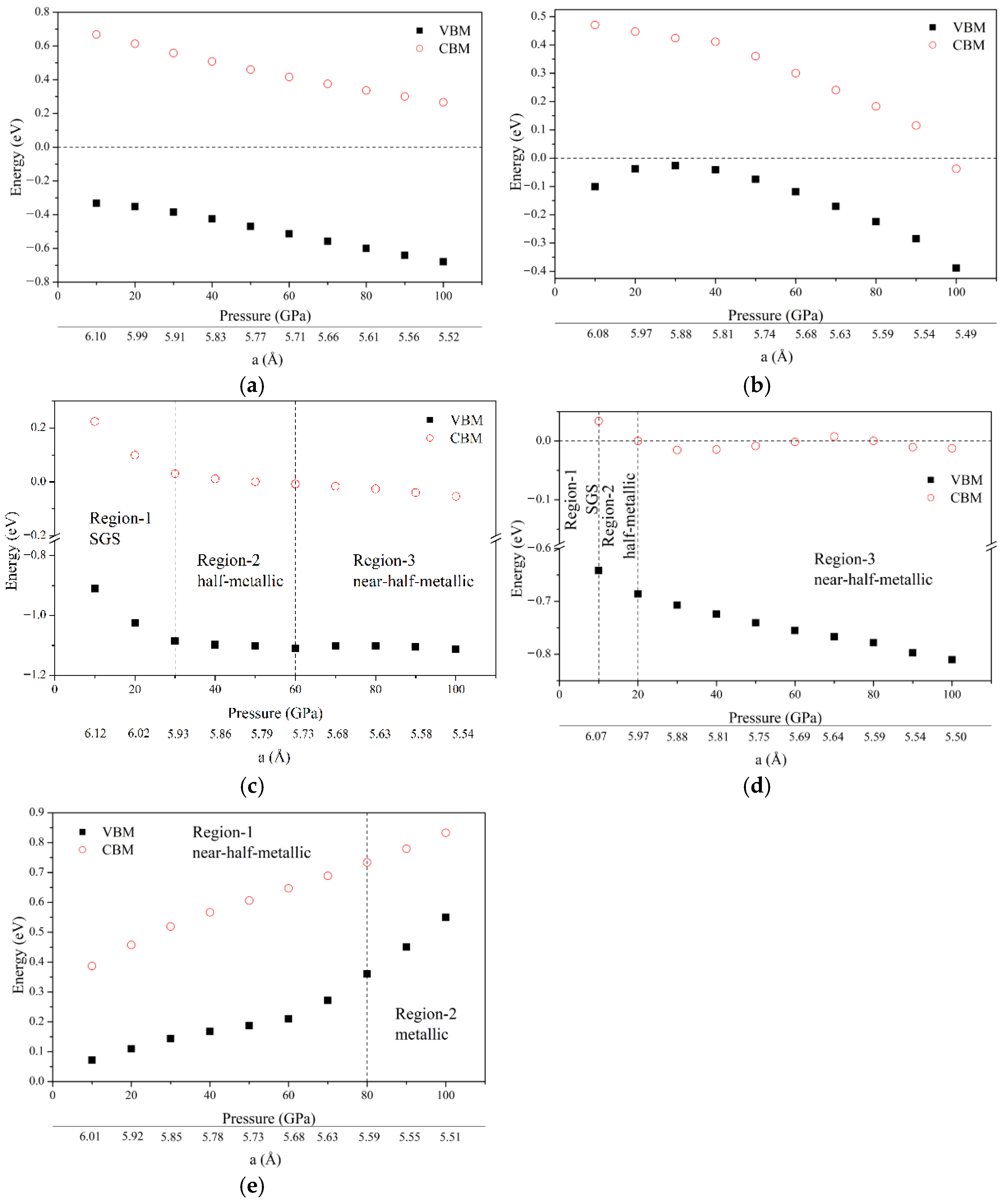

3.4. Pressure Effect

4. Conclusions

- Ground State Properties: At equilibrium, ZrVFeAl and ZrCrFeGe are half-metals (HMs), ZrVCoAl and ZrCrFeAl are spin gapless semiconductors (SGSs), while ZrCrMnAl and ZrMnFeAl are near-HMs. All exhibit integer total magnetic moments, satisfying the Slater–Pauling rule, and possess 100% spin polarization with significant spin-flip gaps.

- Pressure-Induced Transformations: Under pressure (0–100 GPa), all alloys remain mechanically stable (Born–Huang criteria). Crucially, ZrVFeAl and ZrCrMnAl retain HM character over their entire studied pressure ranges (0–100 GPa and 0–90 GPa, respectively). ZrVCoAl transitions from SGS to HM at ~30 GPa. ZrCrFeAl evolves from SGS (0–10 GPa) to HM (10–20 GPa), becoming near-HM at higher pressures.

- Mechanical Behavior: All studied alloys demonstrate ductility, suggesting favorable processability particularly at lower pressures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Pressure (GPa) | B | G | E | CP | B/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 160.95 | 79.84 | 205.53 | 0.29 | 25.94 | 2.02 |

| 20 | 189.71 | 89.68 | 232.41 | 0.30 | 38.59 | 2.12 |

| 30 | 215.66 | 98.15 | 255.66 | 0.30 | 50.71 | 2.20 |

| 40 | 239.73 | 105.81 | 276.71 | 0.31 | 62.30 | 2.27 |

| 50 | 262.70 | 112.97 | 296.42 | 0.31 | 73.62 | 2.33 |

| 60 | 284.71 | 119.58 | 314.69 | 0.32 | 84.90 | 2.38 |

| 70 | 305.92 | 125.62 | 331.49 | 0.32 | 96.31 | 2.44 |

| 80 | 326.19 | 130.88 | 346.30 | 0.32 | 107.93 | 2.49 |

| 90 | 345.65 | 135.65 | 359.87 | 0.33 | 119.56 | 2.55 |

| 100 | 364.64 | 140.05 | 372.46 | 0.33 | 131.11 | 2.60 |

| Pressure (GPa) | B | G | E | CP | B/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 153.08 | 81.74 | 208.17 | 0.27 | 14.01 | 1.87 |

| 20 | 182.73 | 92.19 | 236.76 | 0.28 | 26.92 | 1.98 |

| 30 | 212.64 | 100.20 | 259.79 | 0.30 | 44.19 | 2.12 |

| 40 | 240.21 | 106.89 | 279.26 | 0.31 | 61.12 | 2.25 |

| 50 | 265.79 | 112.50 | 295.78 | 0.32 | 77.79 | 2.36 |

| 60 | 289.44 | 117.40 | 310.24 | 0.32 | 93.61 | 2.47 |

| 70 | 311.83 | 121.97 | 323.71 | 0.33 | 108.53 | 2.56 |

| 80 | 333.00 | 125.73 | 335.03 | 0.33 | 123.39 | 2.65 |

| 90 | 338.25 | 126.34 | 337.05 | 0.33 | 127.24 | 2.68 |

| 100 | 295.82 | 123.03 | 324.15 | 0.32 | 88.85 | 2.41 |

| Pressure (GPa) | B | G | E | CP | B/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 167.79 | 90.45 | 230.02 | 0.27 | 16.52 | 1.86 |

| 20 | 194.03 | 102.18 | 260.77 | 0.28 | 23.14 | 1.90 |

| 30 | 218.00 | 112.33 | 287.59 | 0.28 | 30.14 | 1.94 |

| 40 | 239.72 | 120.20 | 308.95 | 0.29 | 38.70 | 1.99 |

| 50 | 258.40 | 126.11 | 325.40 | 0.29 | 47.47 | 2.05 |

| 60 | 275.19 | 131.43 | 340.14 | 0.29 | 55.41 | 2.09 |

| 70 | 289.08 | 135.52 | 351.61 | 0.30 | 62.67 | 2.13 |

| 80 | 304.85 | 139.05 | 362.09 | 0.30 | 72.83 | 2.19 |

| 90 | 323.09 | 141.08 | 369.47 | 0.31 | 87.88 | 2.29 |

| 100 | 338.42 | 140.87 | 371.12 | 0.32 | 103.59 | 2.40 |

| Pressure (GPa) | B | G | E | CP | B/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 174.36 | 97.48 | 246.50 | 0.26 | 11.08 | 1.79 |

| 20 | 202.02 | 109.10 | 277.37 | 0.27 | 19.33 | 1.85 |

| 30 | 226.78 | 118.82 | 303.47 | 0.28 | 27.89 | 1.91 |

| 40 | 249.17 | 127.50 | 326.76 | 0.28 | 35.76 | 1.95 |

| 50 | 269.44 | 134.67 | 346.32 | 0.29 | 44.13 | 2.00 |

| 60 | 287.54 | 140.83 | 363.19 | 0.29 | 52.10 | 2.04 |

| 70 | 299.60 | 144.74 | 373.99 | 0.29 | 57.80 | 2.07 |

| 80 | 313.42 | 148.05 | 383.73 | 0.30 | 66.29 | 2.12 |

| 90 | 334.73 | 151.85 | 395.70 | 0.30 | 81.43 | 2.20 |

| 100 | 342.43 | 152.43 | 398.21 | 0.31 | 88.33 | 2.25 |

| Pressure (GPa) | B | G | E | CP | B/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 199.14 | 72.53 | 194.04 | 0.34 | 73.80 | 2.75 |

| 20 | 229.55 | 86.43 | 230.39 | 0.33 | 81.56 | 2.66 |

| 30 | 258.79 | 99.08 | 263.60 | 0.33 | 90.22 | 2.61 |

| 40 | 285.70 | 110.86 | 294.49 | 0.33 | 98.05 | 2.58 |

| 50 | 310.83 | 121.48 | 322.44 | 0.33 | 105.94 | 2.56 |

| 60 | 334.47 | 130.73 | 346.98 | 0.33 | 114.67 | 2.56 |

| 70 | 355.37 | 138.58 | 367.92 | 0.33 | 122.95 | 2.56 |

| 80 | 376.31 | 146.54 | 389.10 | 0.33 | 131.04 | 2.57 |

| 90 | 395.83 | 153.83 | 408.56 | 0.33 | 138.76 | 2.57 |

| 100 | 409.42 | 159.74 | 424.08 | 0.33 | 142.82 | 2.56 |

| Pressure (GPa) | B | G | E | CP | B/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 185.83 | 90.02 | 232.51 | 0.29 | 33.73 | 2.06 |

| 20 | 211.91 | 102.90 | 265.70 | 0.29 | 38.74 | 2.06 |

| 30 | 234.22 | 114.37 | 295.08 | 0.29 | 42.40 | 2.05 |

| 40 | 253.18 | 123.99 | 319.76 | 0.29 | 45.77 | 2.04 |

| 50 | 270.07 | 133.56 | 343.97 | 0.29 | 47.09 | 2.02 |

| 60 | 294.98 | 141.41 | 365.77 | 0.29 | 59.21 | 2.09 |

| 70 | 312.53 | 148.14 | 383.79 | 0.29 | 65.63 | 2.11 |

| 80 | 333.54 | 154.52 | 401.55 | 0.30 | 75.92 | 2.16 |

| 90 | 356.34 | 158.77 | 414.72 | 0.31 | 91.22 | 2.24 |

| 100 | 382.87 | 163.52 | 429.43 | 0.31 | 109.21 | 2.34 |

References

- Chadov, S.; Graf, T.; Chadova, K.; Dai, X.F.; Casper, F.; Fecher, G.H.; Felser, C. Efficient Spin Injector Scheme Based on Heusler Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 047202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.L.; Wan, P.; Xue, M.A. Structural, Electronic, Magnetic, and Elastic Properties of CoX’CrZ (X’ = Sc, Ti; Z = Al, Ga) Quaternary Heusler Alloys: First-Principles Study. Phys. Status Solidi B 2021, 258, 2100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wederni, A.; Daza, J.; Mbarek, W.B.; Saurina, J.; Escoda, L.; Sun, J.J. Crystal Structure and Properties of Heusler Alloys: A Comprehensive Review. Metals 2024, 14, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.M.; Mohammed, S.; Jafar, A.; Bouhemadou, A.; Baadji, N. Multifunctional Properties of FeMnScAl Quaternary Heusler Alloy: Insights into Spintronics, Photovoltaics, and Thermoelectric Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 2672–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.P.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, T.; Sun, X.W.; Song, T.; Guo, P.; Deng, J.B. Stability, electronic and magnetic properties investigations on Zr2YZ (Y = Co, Cr, V and Z = Al, Ga, In, Pb, Sn, Tl) compounds. Mater. Res. Bul. 2017, 86, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainsla, L.; Suzuki, K.Z.; Tsujikawa, M.; Tsuchiura, H.; Shirai, M.; Mizukami, S. Magnetic tunnel junctions with an equiatomic quaternary CoFeMnSi Heusler alloy electrode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 052403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, X.; Lin, Y.; Gao, G.Y. Search for half-metallic magnets with large half-metallic gaps in the quaternary Heusler alloys CoFeTiZ and CoFeVZ (Z = Al, Ga, Si, Ge, As, Sb). J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 360, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.A.; Mueller, F.M.; Engen, P.G.V.; Buschow, K.H.J. New class of materials: Half-metallic ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprakash, P.; Muthu, S.E.; Singh, A.K.; Dubey, K.K.; Kannan, M.; Muthukumaran, S.; Guha, S.; Kar, M.; Singh, S.; Arumugam, S. Effect of chemical and external hydrostatic pressure on magnetic and magnetocaloric properties of Pt doped Ni2MnGa shape memory Heusler alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 514, 167136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugino, O.; Car, R. Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Study of First-Order Phase Transitions: Melting of Silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, D.; Yao, Y.G.; Feng, W.X.; Wen, J.; Zhu, W.G.; Chen, X.Q.; Stocks, G.M.; Zhang, Z.Y. Half-Heusler Compounds as a New Class of Three-Dimensional Topological Insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 096404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadov, S.; Wu, S.C.; Felser, C. Stability of Weyl points in magnetic half-metallic Heusler compounds. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 024435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, C.K.; Mondal, C.; Pathak, B.; Alam, A. Quaternary Heusler alloy: An ideal platform to realize triple point fermions. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 045144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacimi, S.; Mehnane, H.; Zaoui, A. I-II-V and I-III-IV half-Heusler compounds for optoelectronic applications: Comparative ab initio study. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 587, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunok, H.Y.; Karaca, E.; Bağcı, S.; Tütüncü, H.M. Physical properties and superconductivity of Heusler compound LiGa2Rh: A first-principles calculation. Solid State Commun. 2020, 311, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.P.; Gao, P.F.; Zhang, Y.L. Investigations on Gilbert damping, Curie temperatures and thermoelectric properties in CoFeCrZ quaternary Heusler alloys. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2020, 20, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandy, S.A.; Chai, J.D. Robust stability, half-metallic ferrimagnetism and thermoelectric properties of new quaternary Heusler material: A first principles approach. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 502, 166562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.Y.; Hu, L.; Yao, K.L.; Luo, B.; Liu, N. Large half-metallic gaps in the quaternary Heusler alloys CoFeCrZ (Z = Al, Si, Ga, Ge): A first-principles study. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 551, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forozani, G.; Abadi, A.A.M.; Baizaee, S.M.; Gharaati, A. Structural, electronic and magnetic properties of CoZrIrSi quaternary Heusler alloy: First-principles study. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 815, 152449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Dou, S.X.; Zhang, C. Zero-gap materials for future spintronics, electronics and optics. NPG Asia Mater. 2010, 2, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Zhang, J.M.; Ali, A.; Rehman, M.U.; Muhammad, S. Structural, mechanical, thermal, magnetic, and electronic properties of the RhMnSb half-Heusler alloy under pressure. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 251, 123110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdoğan, K.; Şaşıoğlu, E.; Galanakis, I. Slater-Pauling behavior in LiMgPdSn-type multifunctional quaternary Heusler materials: Half-metallicity, spin-gapless and magnetic semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 193903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.H.; He, J.G.; Mazumdar, D.; Munira, K.; Keshavarz, S.; Lovorn, T.; Wolverton, C.; Ghosh, A.W.; Butler, W.H. Computational investigation of inverse Heusler compounds for spintronics applications. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 094410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Opahle, I.; Zhang, H.B. High-throughput screening for spin-gapless semiconductors in quaternary Heusler compounds. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 024410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoat, D.M.; Naseri, M. Examining the half-metallicity and thermoelectric properties of new equiatomic quaternary Heusler compound CoVRhGe under pressure. Phys. B 2020, 583, 412058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seema, K. The effect of pressure and disorder on half-metallicity of CoRuFeSi Quaternary Heusler alloy. Intermetallics 2019, 110, 106478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, Z.X.; Wang, X.T.; Khenata, R.; Rozale, H. First-Principles Investigation of Equiatomic QuaternaryHeusler Alloys NbVMnAl and NbFeCrAl and a Discussion of the Generalized Electron-Filling Rule. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.Y.; Tan, M.; Khenata, R.; Wang, X.T.; Yang, T. Computational study of the electronic, magnetic, mechanical and thermodynamic properties of new equiatomic quaternary heusler compounds TiZrRuZ (Z = Al, Ga, In). Chin. J. Phys. 2019, 62, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 14251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.K.; Liu, G.D.; Wang, X.T.; Rozale, H.; Wang, L.Y.; Khenata, R.; Wu, Z.M.; Dai, X.F. First-principles study on quaternary Heuslercompounds ZrFeVZ (Z = Al, Ga, In) with large spin-flip gap. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, K.; Ahmadian, F. First-Principles Study of Magnetism and Half-MetallicProperties for the Quaternary Heusler Alloys CoRhYZ (Y = Sc, Ti, Cr, and Mn; Z = Al, Si, and P). J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2017, 30, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Huang, K. Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhat, F.; Coudert, F.X. Necessary and sufficient elastic stability conditions in various crystal systems. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 224104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.; Hassan, S.; Arshad, H.; Rizwan, M.; Gillani, S.S.A.; Rafique, M.; Zafar, M.; Ahmed, S. Theoretical investigation of structural, magnetic and elastic properties of half Heusler LiCrZ (Z = P, As, Bi, Sb) alloys. Phys. B 2019, 575, 411677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W. Lehrbuch der Kristallphysik; Springer: Leipzig, Germany, 1928; p. 978. [Google Scholar]

- Reuss, A.; Angew, Z. Calculation of the flow limits of mixed crystals on the basis of the plasticity of monocrystals. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 1929, 9, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. A 1952, 65, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Bao, L.K.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, M.J.; Duan, Y.H. Insight into structural, electronic, elastic and thermal properties of A15-type Nb3X (X = Si, Ge, Sn and Pb) compounds. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Arshad, H.; Rizwan, M.; Gillani, S.S.A.; Zafar, M.; Ahmed, S.; Shakil, M. Investigation of structural, electronic, magnetic and mechanical properties of a new series of equiatomic quaternary Heusler alloys CoYCrZ (Z = Si, Ge, Ga, Al): A DFT study. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 819, 152964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Mehmood, N. A first principle study of half-Heusler compounds CrTiZ (Z = P, As). J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2017, 31, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, X.R.; Zhou, T.; Yuan, H.K.; Chen, H. Structural stability, half-metallicity and magnetismof the CoFeMnSi/GaAs (001) interface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 346, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.H.; Wei, Q.; Copple, A. Strain-engineered direct-indirect band gap transition and its mechanism in two-dimensional phosphorene. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 085402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| s1 | s2 | s3 | s1 | s2 | s3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Γ | 0 | 0 | 0 | K | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.75 |

| X | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | L | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| W | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.75 | U | 0.625 | 0.25 | 0.625 |

| Type | X | X′ | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y-I | 4a(0,0,0) | 4c(0.25,0.25,0.25) | 4d(0.75,0.75,0.75) | 4b(0.5,0.5,0.5) |

| Y-II | 4a(0,0,0) | 4b(0.5,0.5,0.5) | 4c(0.25,0.25,0.25) | 4d(0.75,0.75,0.75) |

| Y-III | 4a(0,0,0) | 4c(0.25,0.25,0.25) | 4b(0.5,0.5,0.5) | 4d(0.75,0.75,0.75) |

| Complexes (Our Work) | Types | Formation Energy Ef (eV) | Other Similar Complexes | Formation Energy Ef (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZrVFeAl | Y-I | −1.37 | CoFeCrAl [18] | −0.86 |

| ZrCrMnAl | Y-I | −0.33 | CoFeCrGa [18] | −0.52 |

| ZrVCoAl | Y-I | −1.54 | CoFeCrSi [18] | −1.48 |

| ZrCrFeAl | Y-I | −1.33 | CoFeCrGe [18] | −0.66 |

| ZrCrFeGe | Y-I | −0.97 | CoFeMnAl [18] | −1.31 |

| ZrMnFeAl | Y-I | −1.55 | CoFeMnGa [18] | −0.82 |

| Y-I | CoFeMnSi [18] | −1.96 | ||

| CoFeMne [18] | −1.15 |

| Alloys | ZrVFeAl | ZrCrMnAl | ZrVCoAl | ZrCrFeAl | ZrCrFeGe | ZrMnFeAl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| state | Y-I | Y-I | Y-I | Y-I | Y-I | Y-I |

| a | 6.24 | 6.20 | 6.25 | 6.19 | 6.12 | 6.11 |

| C11 | 198.74 | 207.23 | 229.19 | 241.28 | 218.25 | 227.17 |

| C12 | 92.77 | 96.84 | 91.35 | 93.60 | 139.80 | 115.40 |

| C44 | 79.49 | 80.15 | 81.16 | 90.35 | 74.28 | 89.01 |

| B | 128.10 | 133.64 | 137.29 | 142.83 | 165.95 | 152.65 |

| G | 67.56 | 69.02 | 76.02 | 83.34 | 57.49 | 73.86 |

| E | 172.38 | 176.65 | 192.53 | 209.31 | 154.61 | 190.80 |

| 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.29 | |

| B/G | 1.90 | 1.94 | 1.81 | 1.71 | 2.89 | 2.07 |

| CP | 13.27 | 16.7 | 10.19 | 3.25 | 65.52 | 26.39 |

| Alloys | Mtot | MZr | MX′ | MY | MZ | Eg | EHM | P | Physical Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZrVFeAl | 2.00 | 0.29 | 2.22 | −0.52 | −0.02 | 0.91 | 0.43 | 100% | half-metal |

| ZrCrMnAl | 2.58 | −0.18 | 2.43 | 0.37 | −0.04 | - | - | 5% | near-half-metal |

| ZrVCoAl | 3.00 | 0.31 | 2.50 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 1.10 | 0.35 | 100% | SGS |

| ZrCrFeAl | 3.00 | −0.11 | 2.75 | 0.36 | −0.03 | 0.69 | 0.14 | 100% | SGS |

| ZrCrFeGe | −2.00 | 0.12 | −1.77 | −0.36 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 100% | half-metal |

| ZrMnFeAl | −2.02 | 0.28 | −1.67 | −0.63 | 0.03 | - | - | 95% | near-half-metal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, X.; Liu, S.; Wan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, C. First-Principles Investigation of Zr-Based Equiatomic Quaternary Heusler Compounds Under Hydrostatic Pressure for Spintronics Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231796

Yuan X, Liu S, Wan P, Zhang Z, Tao C. First-Principles Investigation of Zr-Based Equiatomic Quaternary Heusler Compounds Under Hydrostatic Pressure for Spintronics Applications. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231796

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Xiaoli, Sicong Liu, Peng Wan, Zhenjun Zhang, and Chengjun Tao. 2025. "First-Principles Investigation of Zr-Based Equiatomic Quaternary Heusler Compounds Under Hydrostatic Pressure for Spintronics Applications" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231796

APA StyleYuan, X., Liu, S., Wan, P., Zhang, Z., & Tao, C. (2025). First-Principles Investigation of Zr-Based Equiatomic Quaternary Heusler Compounds Under Hydrostatic Pressure for Spintronics Applications. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231796