Study on the Passivation of Defect States in Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells by the Dual Addition of KSCN and KCl

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Chemical Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Precursor Solution with Additives

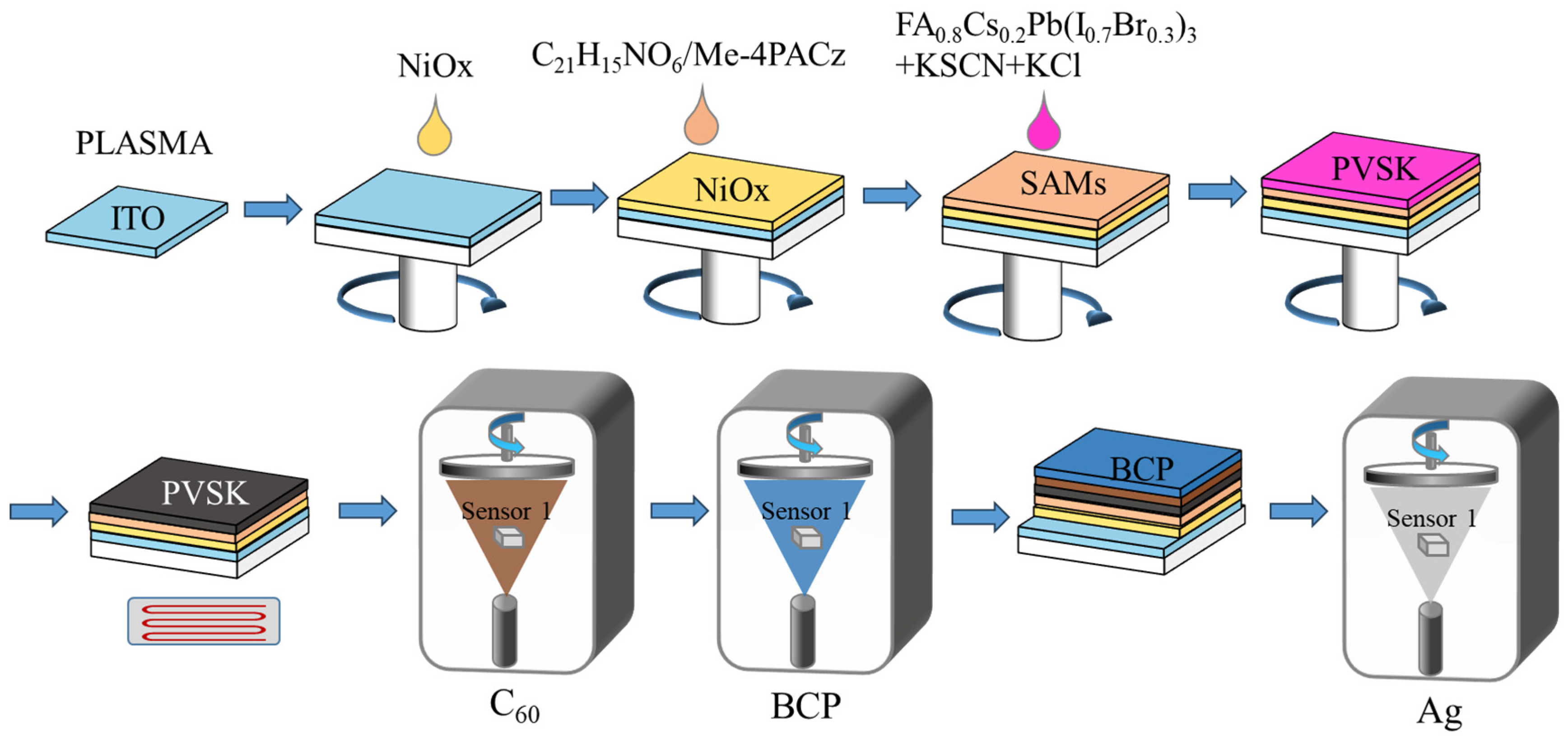

2.3. Fabrication of Perovskite Solar Cells

2.4. Instruments and Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

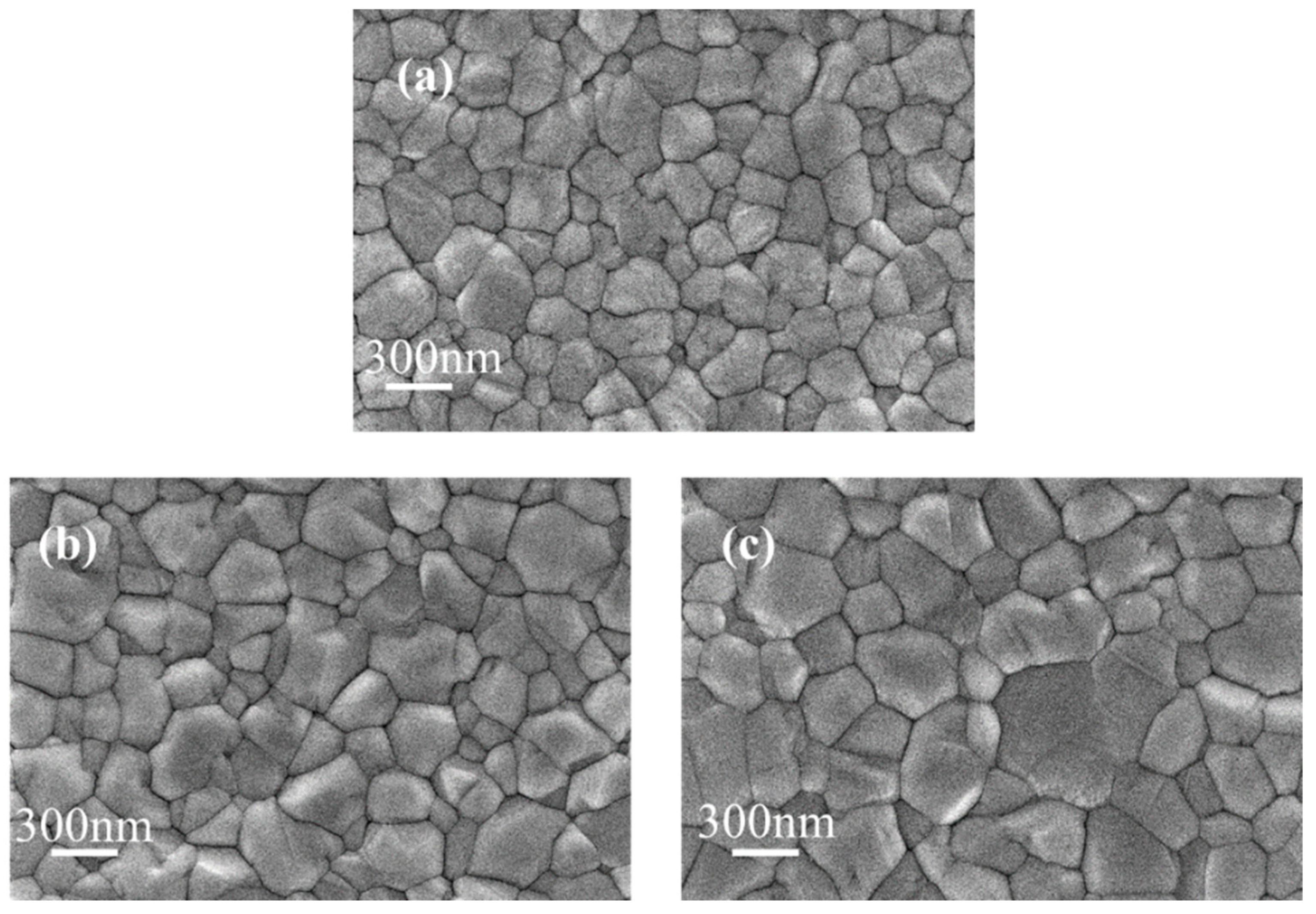

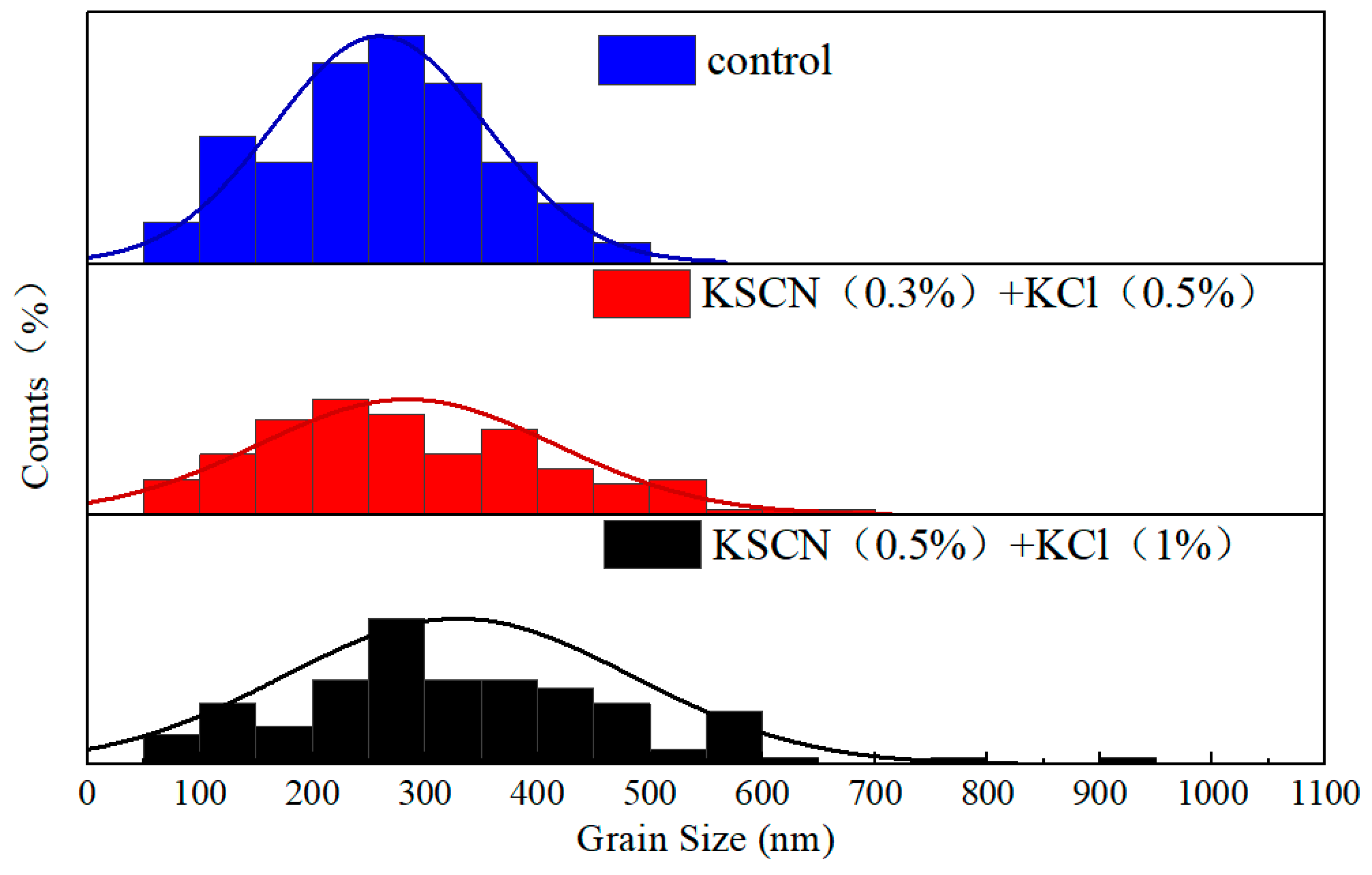

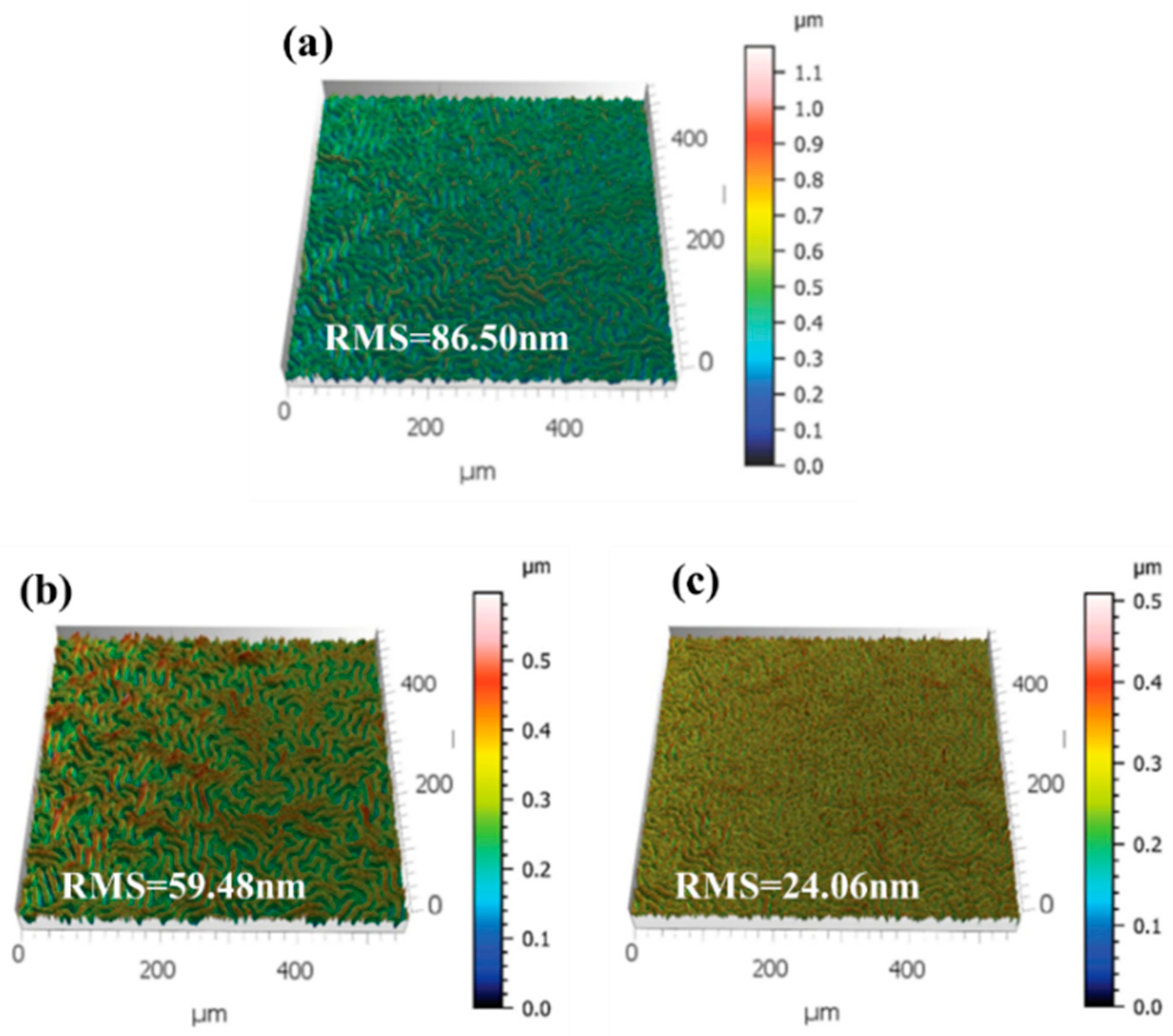

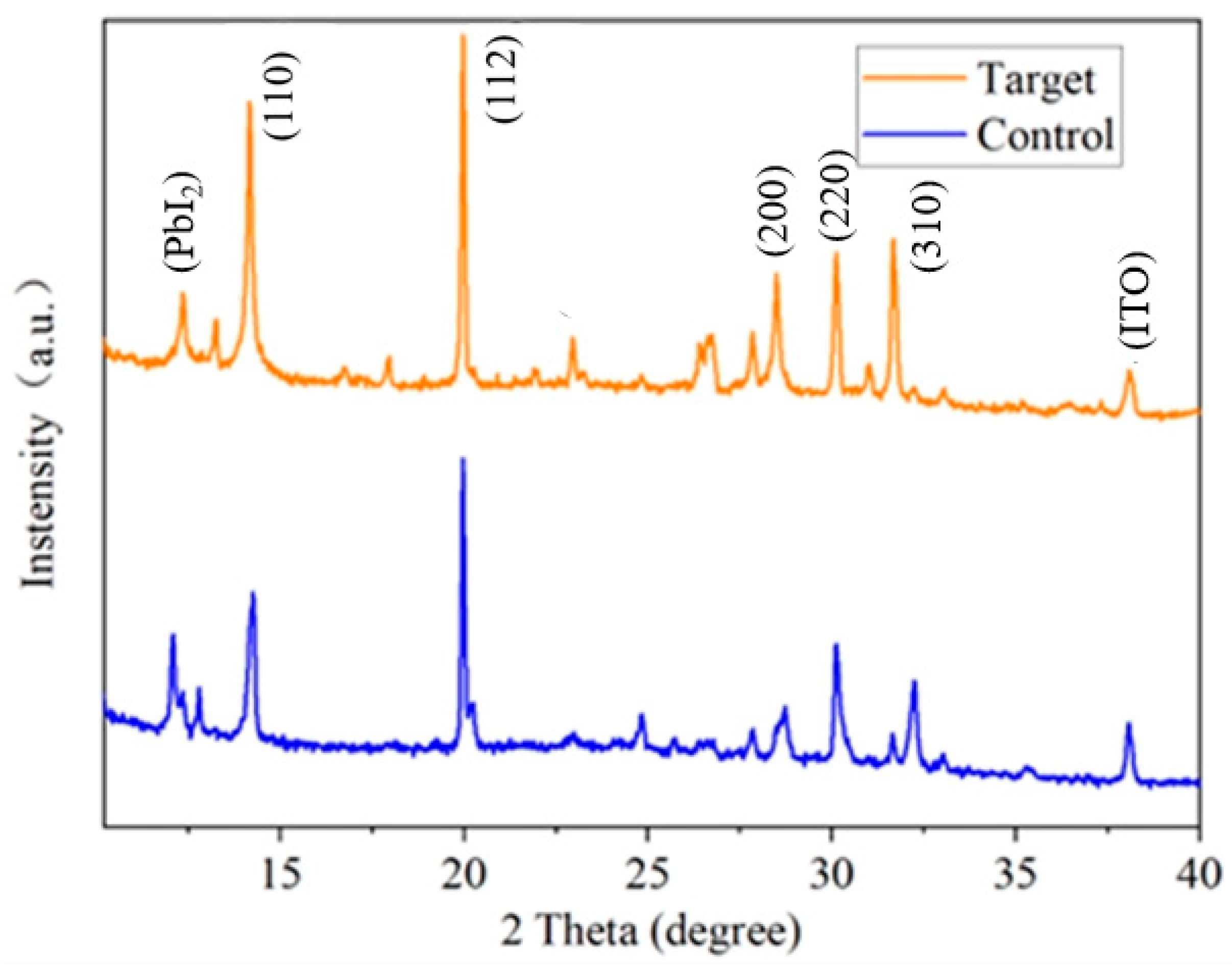

3.1. Effect of KSCN and KCl Dual Additives on the Crystallization Properties of WBG Perovskite Films

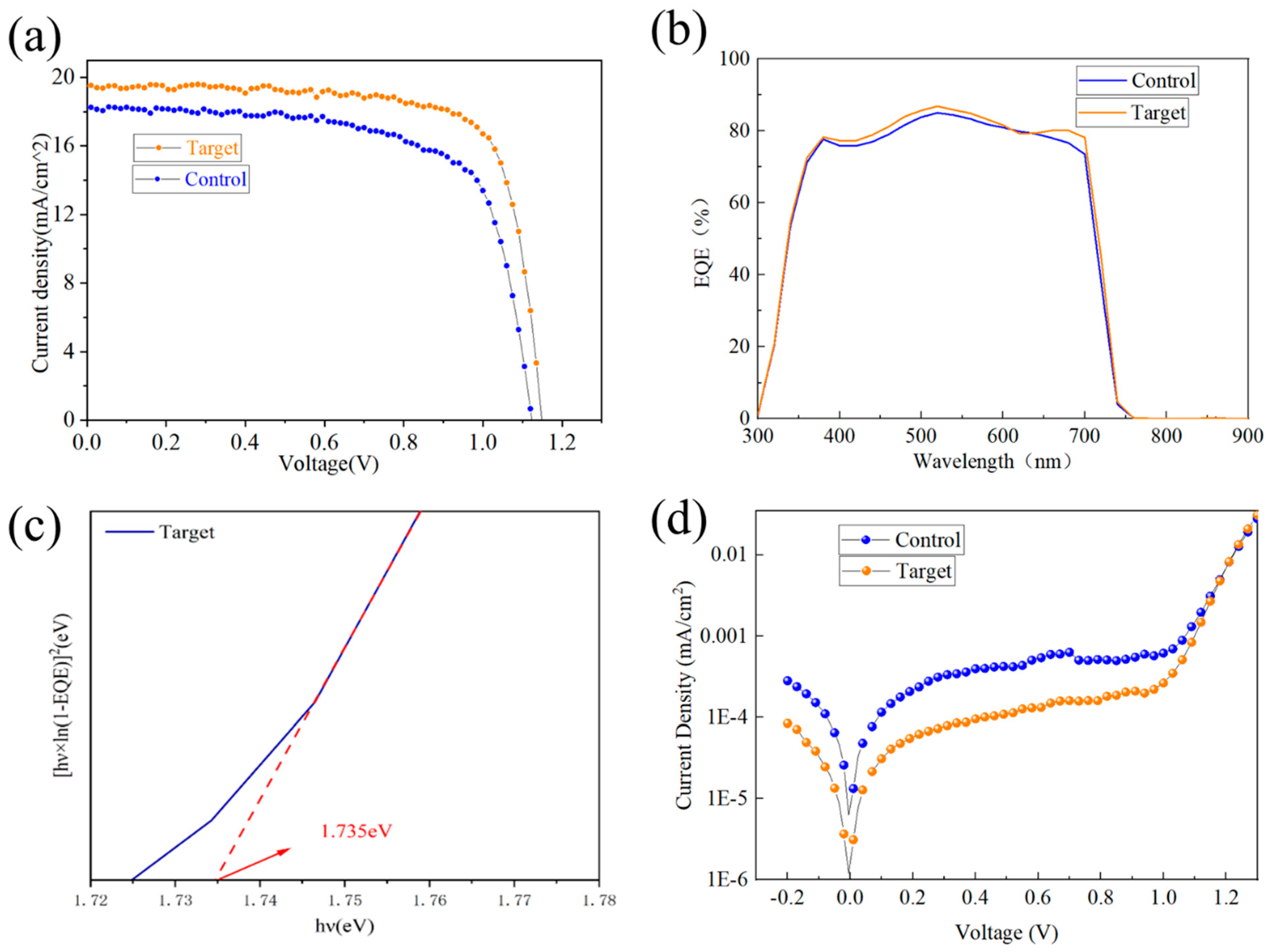

3.2. Effect of KSCN and KCl Dual Additives on Defect Passivation in WBG Perovskite Films

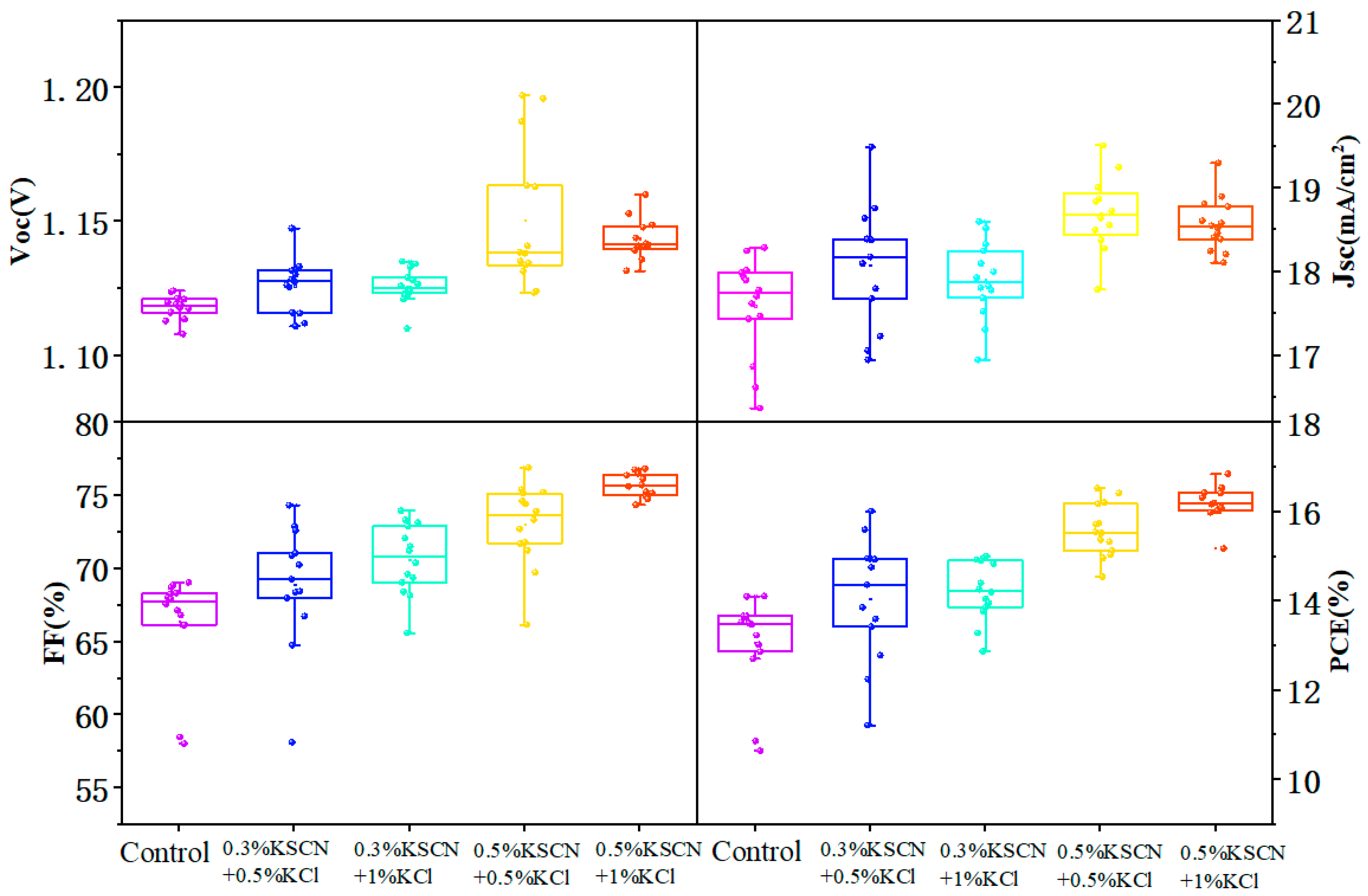

3.3. Effect of KSCN and KCl Dual Additives on the Performance of WBG Perovskite Solar Cells

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cretì, A.; Prete, P.; Lovergine, N.; Lomascolo, M. Enhanced Optical Absorption of GaAs Near-Band-Edge Transitions in GaAs/AlGaAs Core–Shell Nanowires: Implications for Nanowire Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 18149–18158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, P.; Peng, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Surve, S.; Lu, T.; Bui, A.D.; Li, N.; Liang, W.; et al. 27.6% Perovskite/c-Si Tandem Solar Cells Using Industrial Fabricated TOPCon Device. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, A.; Schmager, R.; Fassl, P.; Noack, P.; Wattenberg, B.; Dippell, T.; Ulrich, W. Paetzold. Efficient Light Harvesting in Thick Perovskite Solar Cells Processed on Industry-Applicable Random Pyramidal Textures. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 6700–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Hao, H.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, C.; Dong, J.; Xing, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Light Trapping Effect in Perovskite Solar Cells by the Addition of Ag Nanoparticles, Using Textured Substrates. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obraztsova, A.A.; Barettin, D.; Furasova, A.D.; Voroshilov, P.M.; Auf der Maur, M.; Orsini, A.; Makarov, S.V. Light-Trapping Electrode for the Efficiency Enhancement of Bifacial Perovskite Solar Cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Hua, X.; Zhu, X.; Ding, Y.-A.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, S.-T.; Li, D. Monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells with optimized front zinc doped indium oxides and industrial textured silicon heterojunction solar cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 932, 167640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Chen, P.; Hou, F.; Wang, Q.; Pan, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, X. Cerium-doped indium oxide transparent electrode for semi-transparent perovskite and perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells. Sol. Energy 2020, 196, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Pang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhu, W.; Xi, H.; Chang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Hao, Y. Improving Electron Extraction Ability and Device Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells Using a Compatible PCBM/AZO Electron Transporting Bilayer. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Shi, B.; Li, Y.; Yan, L.; Duan, W.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Ren, N.; Han, W.; Liu, J.; et al. Conductive Passivator for Efficient Monolithic Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cell on Commercially Textured Silicon. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2202404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; De Bastiani, M.; Aydin, E.; Harrison, G.T.; Gao, Y.; Pradhan, R.R.; Eswaran, M.K.; Mandal, M.; Yan, W.; Seitkhan, A.; et al. Efficient and stable perovskite-silicon tandem solar cells through contact displacement by MgFx. Science 2022, 377, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, S.; Alzahmi, S.; Salem, I.B.; Obaidat, I.M. Perovskite-Surface-Confined Grain Growth for High-Performance Perovskite Solar Cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Li, Y.; Shi, B.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Han, W.; Ren, N.; Huang, Q.; et al. Reducing electrical losses of textured monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells by tailoring nanocrystalline silicon tunneling recombination junction. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 245, 111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, S.; Ghosh, K. Analysis of Silicon-perovskite Tandem Solar Cells with Transition Metal Oxides as Carrier Selective Contact Layers. Silicon 2022, 14, 10849–10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hang, P.; Li, B.; Hu, Z.; Kan, C.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Yu, X. Phase-Stable Wide-Bandgap Perovskites for Four-Terminal Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells with Over 30% Efficiency. Small 2022, 18, 2203319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Luo, H.; Li, H.; Xia, R.; Zheng, X.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; et al. Efficient Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells on Industrially Compatible Textured Silicon. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2207883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löper, P.; Moon, S.-J.; Martín de Nicolas, S.; Niesen, B.; Ledinsky, M.; Nicolay, S.; Bailat, J.; Yum, J.-H.; De Wolf, S.; Ballif, C. Organic–inorganic halide perovskite/crystalline silicon four-terminal tandem solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bastiani, M.; Mirabelli, A.J.; Hou, Y.; Gota, F.; Aydin, E.; Allen, T.G.; Troughton, J.; Subbiah, A.S.; Isikgor, F.H.; Liu, J.; et al. Efficient bifacial monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells via bandgap engineering. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Choi, I.W.; Go, E.M.; Cho, Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, B.; Jeong, S.; Jo, Y.; Choi, H.W.; Lee, J.; et al. Stable perovskite solar cells with efficiency exceeding 24.8% and 0.3-V voltage loss. Science 2020, 369, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Walter, D.; Chang, N.; Bullock, J.; Kang, D.; Phang, S.P.; Weber, K.; White, T.; Macdonald, D.; Catchpole, K.; et al. Stability challenges for the commercialization of perovskite-silicon tandem solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isikgor, F.H.; Furlan, F.; Liu, J.; Ugur, E.; Eswaran, M.K.; Subbiah, A.S.; Yengel, E.; De Bastiani, M.; Harrison, G.T.; Zhumagali, S.; et al. Concurrent cationic and anionic perovskite defect passivation enables 27.4% perovskite/silicon tandems with suppression of halide segregation. Joule 2021, 5, 1566–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos-Outón, L.M.; Xiao, T.P.; Yablonovitch, E. Fundamental Efficiency Limit of Lead Iodide Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, L.K.; Liu, S.; Qi, Y. Reducing Detrimental Defects for High-Performance Metal Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6676–6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahesh, S.; Ball, J.M.; Oliver, R.D.; McMeekin, D.P.; Nayak, P.K.; Johnston, M.B.; Snaith, H.J. Revealing the origin of voltage loss in mixed-halide perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.M.; Petrozza, A. Defects in perovskite-halides and their effects in solar cells. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, S.G.; Patel, J.B.; Oliver, R.D.; Snaith, H.J.; Johnston, M.B.; Herz, L.M. Phase segregation in mixed-halide perovskites affects charge-carrier dynamics while preserving mobility. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, R.; Xu, Z.; Larson, B.; Rand, B. The Role of Halide Oxidation in Perovskite Halide Phase Separation. Joule 2021, 5, 2273–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, B.; Yu, W.; Li, C. Enhancing perovskite solar cells performance via sewing up the grain boundary. Nano Energy 2023, 115, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Du, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, L.; An, Z.; Jen, A.K.Y.; You, J.; Liu, S. Understanding microstructural development of perovskite crystallization for high performance solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2306947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Ma, T.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Yu, Z.; Sun, W.; Wang, A. Reduced 0.418 VV OC-deficit of 1.73 eV wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells assisted by dual chlorides for efficient all-perovskite tandems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, M.; Seo, J.; Lu, H.; Ahlawat, P.; Mishra, A.; Yang, Y.; Hope, M.A.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Kim, M. Pseudo-halide anion engineering for α-FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. Nature 2021, 592, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Shen, W.; Cai, H.; Dong, W.; Bai, C.; Zhao, J.; Huang, F.; Cheng, Y.B.; Zhong, J. Multifunctional Organic Potassium Salt Additives as the Efficient Defect Passivator for High-Efficiency and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W. Additive and interface passivation dual synergetic strategy enables reduced voltage loss in wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells. Nano Energy 2024, 128, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Jiang, X.; Cao, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Shen, Y.; Yang, H.; Cheng, Q. Suppression of phase segregation in wide-bandgap perovskites with thiocyanate ions for perovskite/organic tandems with 25.06% efficiency. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 92–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gu, Q.; Yin, K.; Tao, L.; Li, Y.; Tan, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, S. Cascaded orbital–oriented hybridization of intermetallic Pd3Pb boosts electrocatalysis of Li-O2 battery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2301439120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, Y.-N.; Wu, W.-Q.; Wang, L. Recent progress of minimal voltage losses for high-performance perovskite photovoltaics. Nano Energy 2021, 81, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Champion Devices | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | Active Area/cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.117 | 18.29 | 69.05 | 14.11 | 0.15 |

| 0.3 mol% + 0.5 mol% KCLKCl | 1.131 | 19.49 | 72.63 | 16.02 | 0.15 |

| 0.3 mol% + 1 mol% | 1.133 | 18.52 | 71.54 | 15.01 | 0.15 |

| 0.5 mol% + 0.5 mol% | 1.187 | 18.46 | 75.41 | 16.53 | 0.15 |

| 0.5 mol% + 1 mol% | 1.148 | 19.51 | 75.17 | 16.85 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Peng, Z.; Yao, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, D. Study on the Passivation of Defect States in Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells by the Dual Addition of KSCN and KCl. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201602

Li M, Peng Z, Yao X, Huang J, Zhang D. Study on the Passivation of Defect States in Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells by the Dual Addition of KSCN and KCl. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(20):1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201602

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Min, Zhaodong Peng, Xin Yao, Jie Huang, and Dawei Zhang. 2025. "Study on the Passivation of Defect States in Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells by the Dual Addition of KSCN and KCl" Nanomaterials 15, no. 20: 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201602

APA StyleLi, M., Peng, Z., Yao, X., Huang, J., & Zhang, D. (2025). Study on the Passivation of Defect States in Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells by the Dual Addition of KSCN and KCl. Nanomaterials, 15(20), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201602