Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (AgCl-NPs) Using a Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Aerial Part Extract and Their Application as Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Green Synthesis of AgCl-NPs

2.3. Characterization of AgCl-NPs

2.4. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities

2.4.1. Microorganisms

2.4.2. Disc Diffusion Method

2.4.3. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.4.4. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC)

2.5. Antioxidant Properties of the Biosynthesized AgCl-NPs

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Visual Confirmation of Green Synthesis of AgCl-NPs

3.2. Characterization of Biosynthesized AgCl-NPs

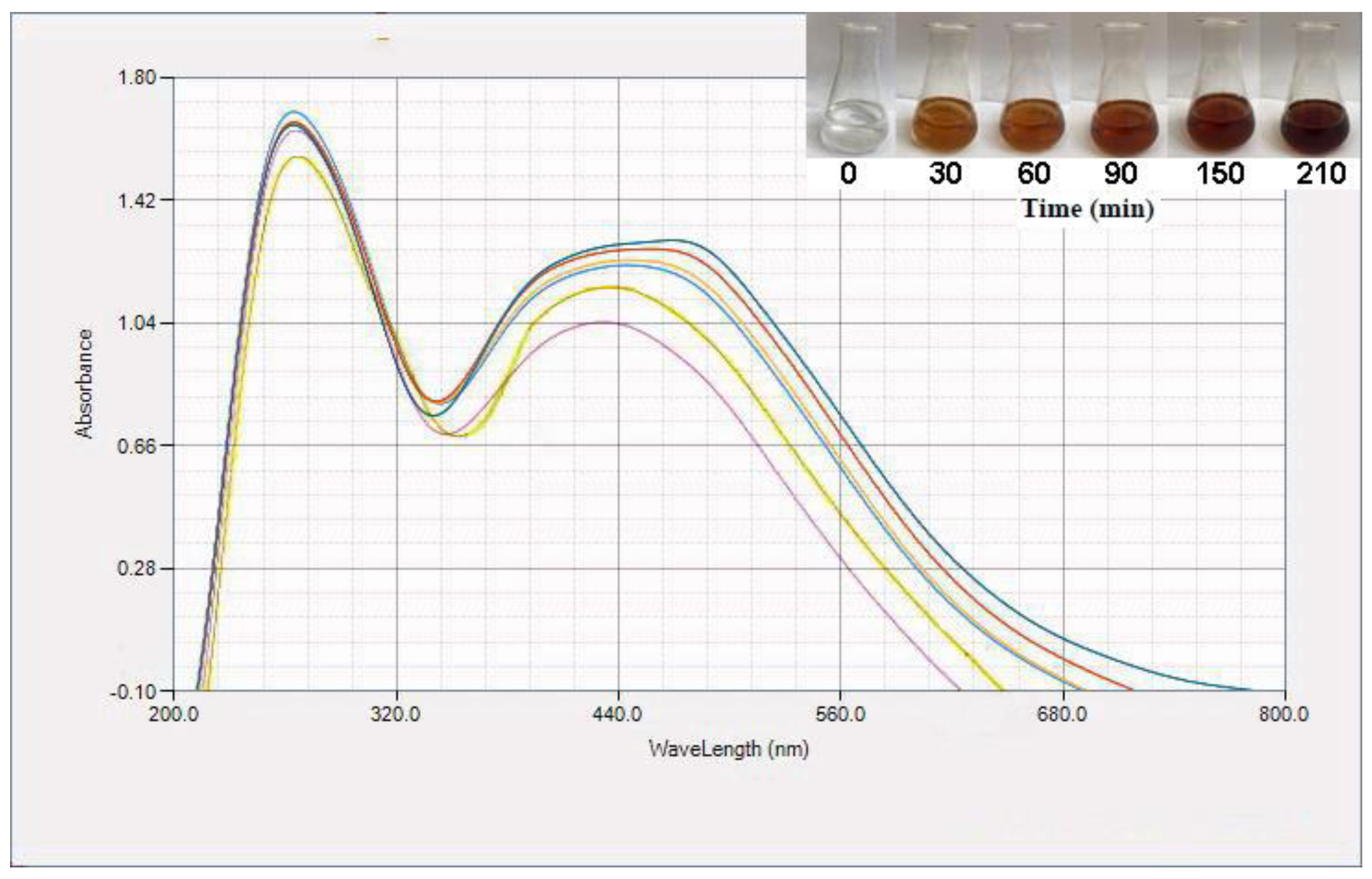

3.2.1. UV–Visible Spectroscopy

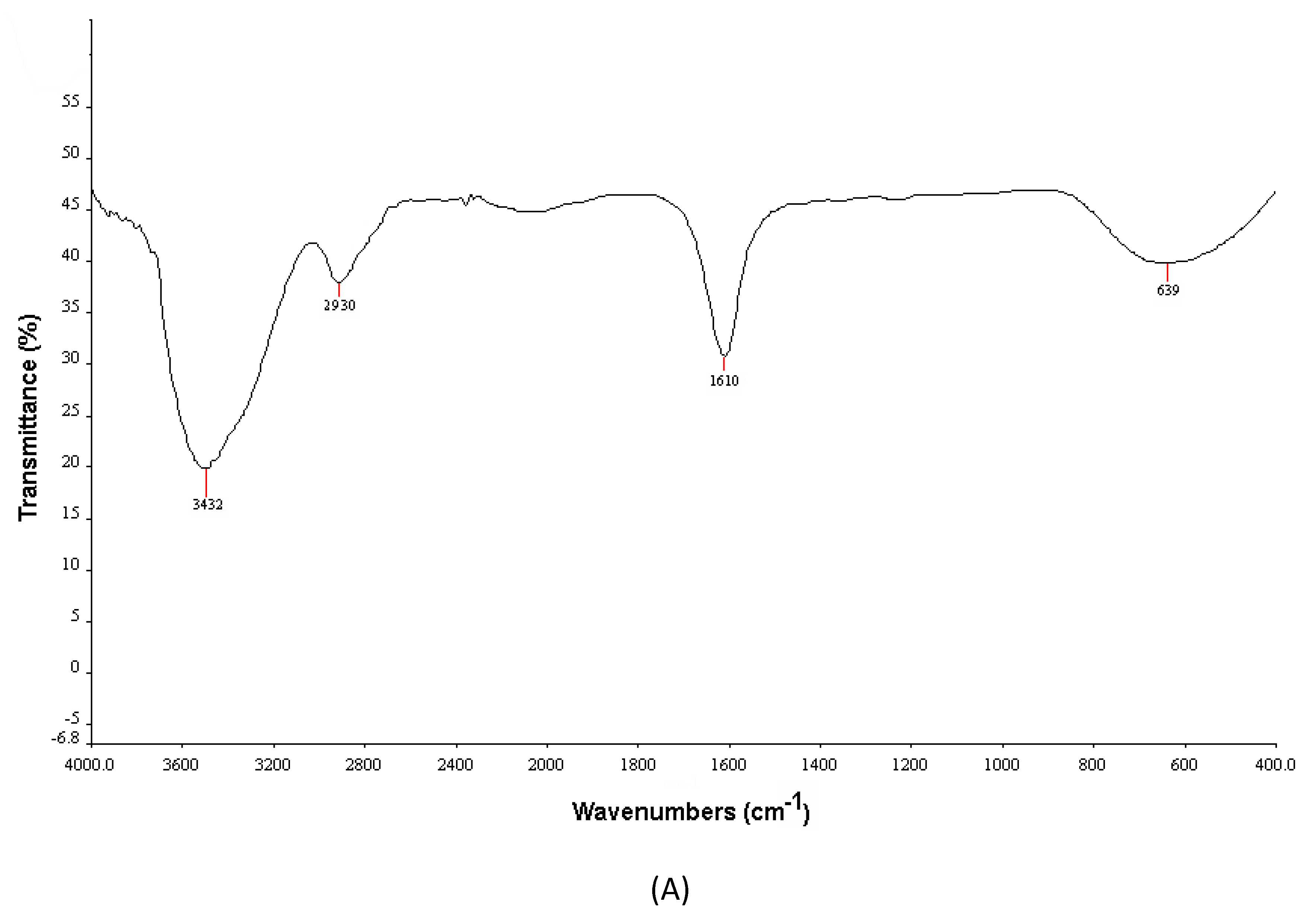

3.2.2. FTIR Spectroscopy

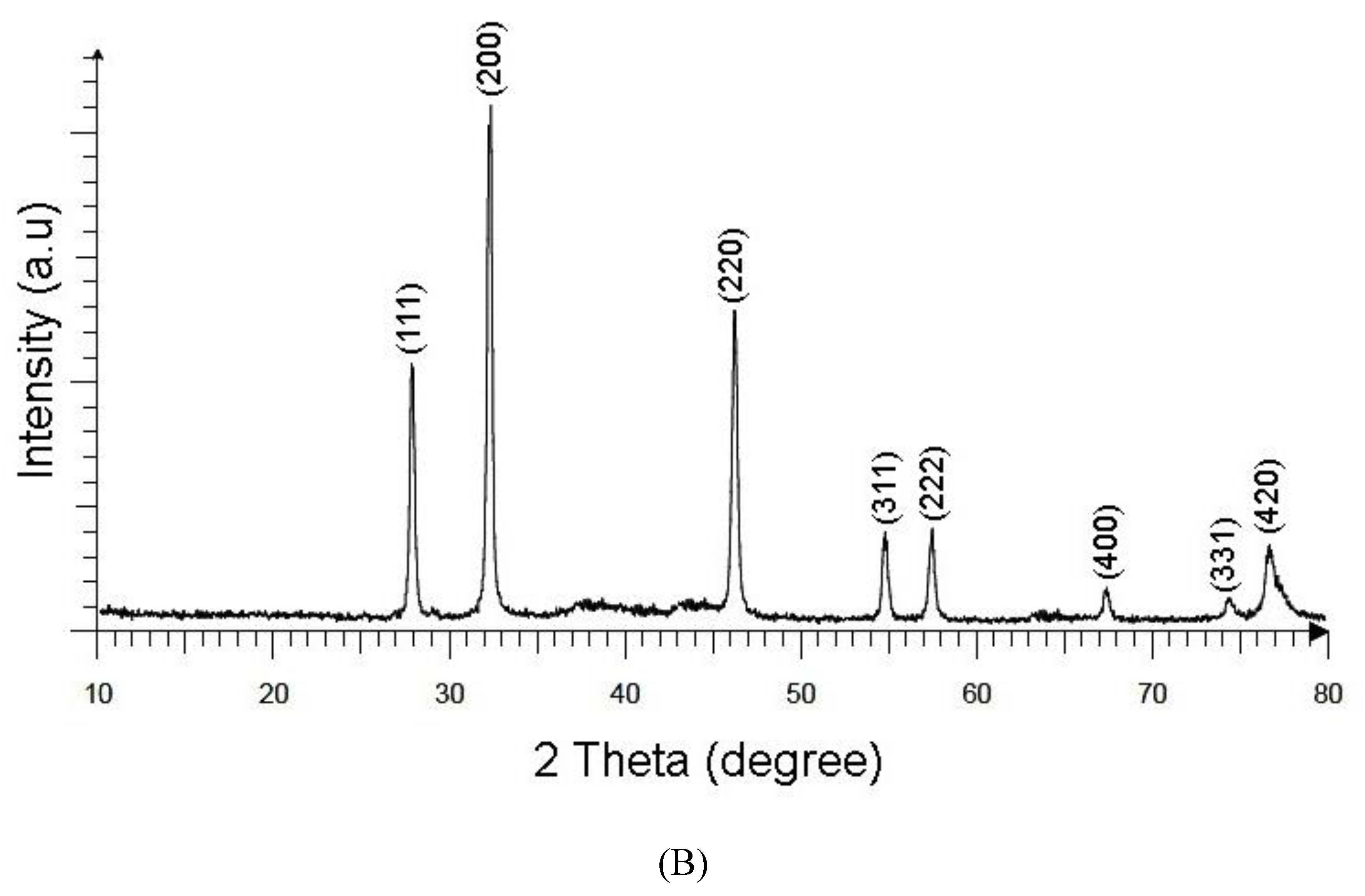

3.2.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

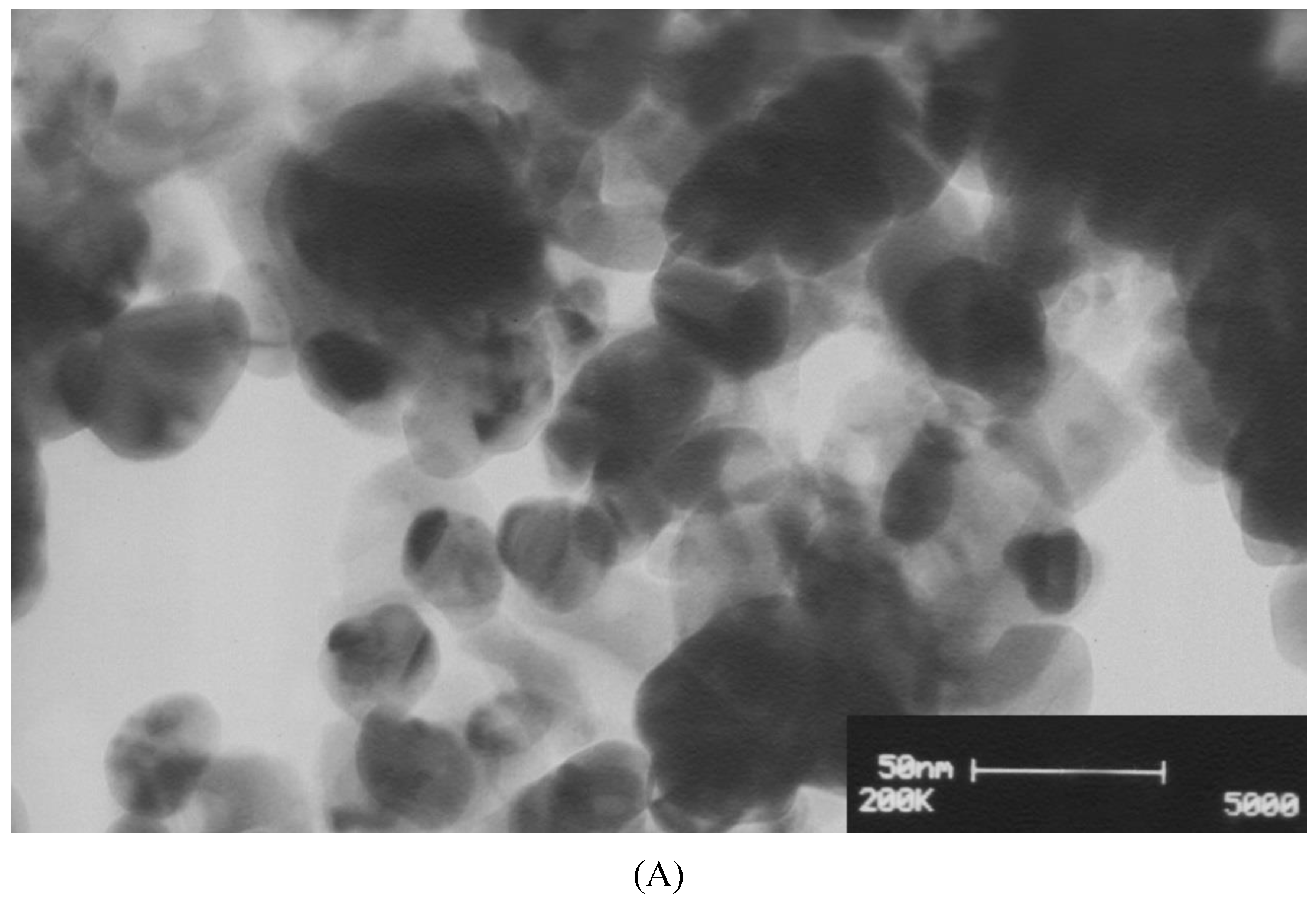

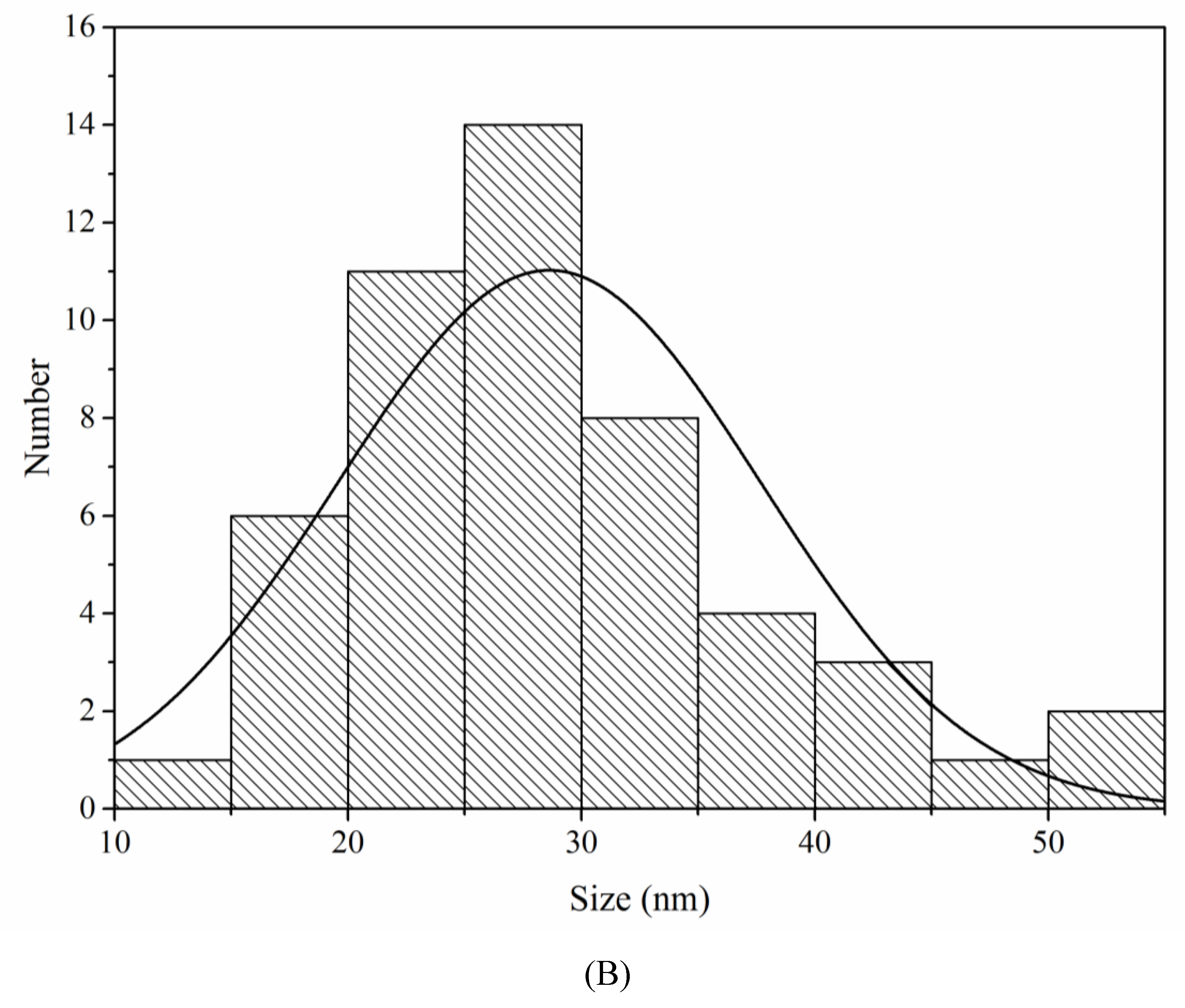

3.2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.3. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities

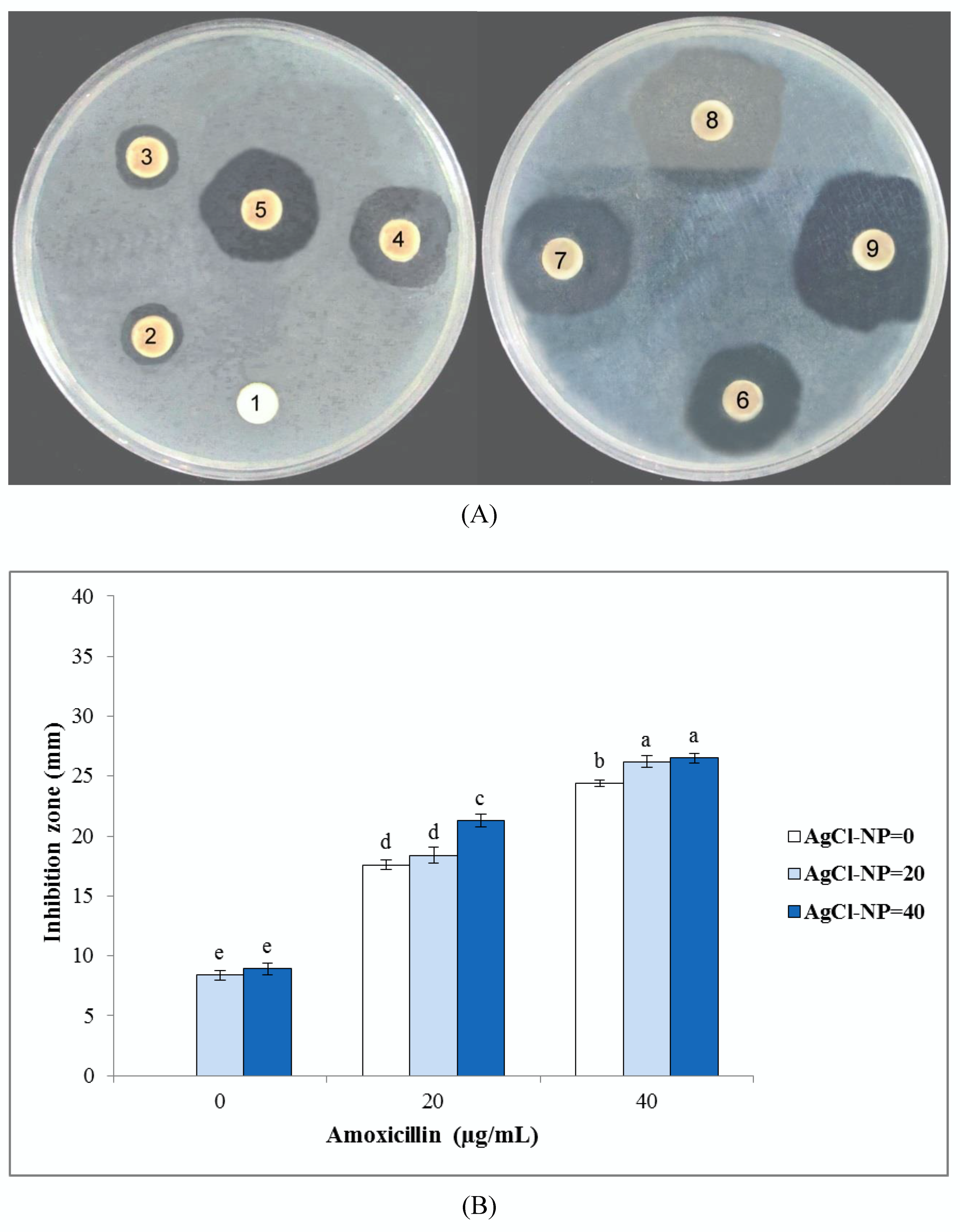

3.3.1. Disc Diffusion Method

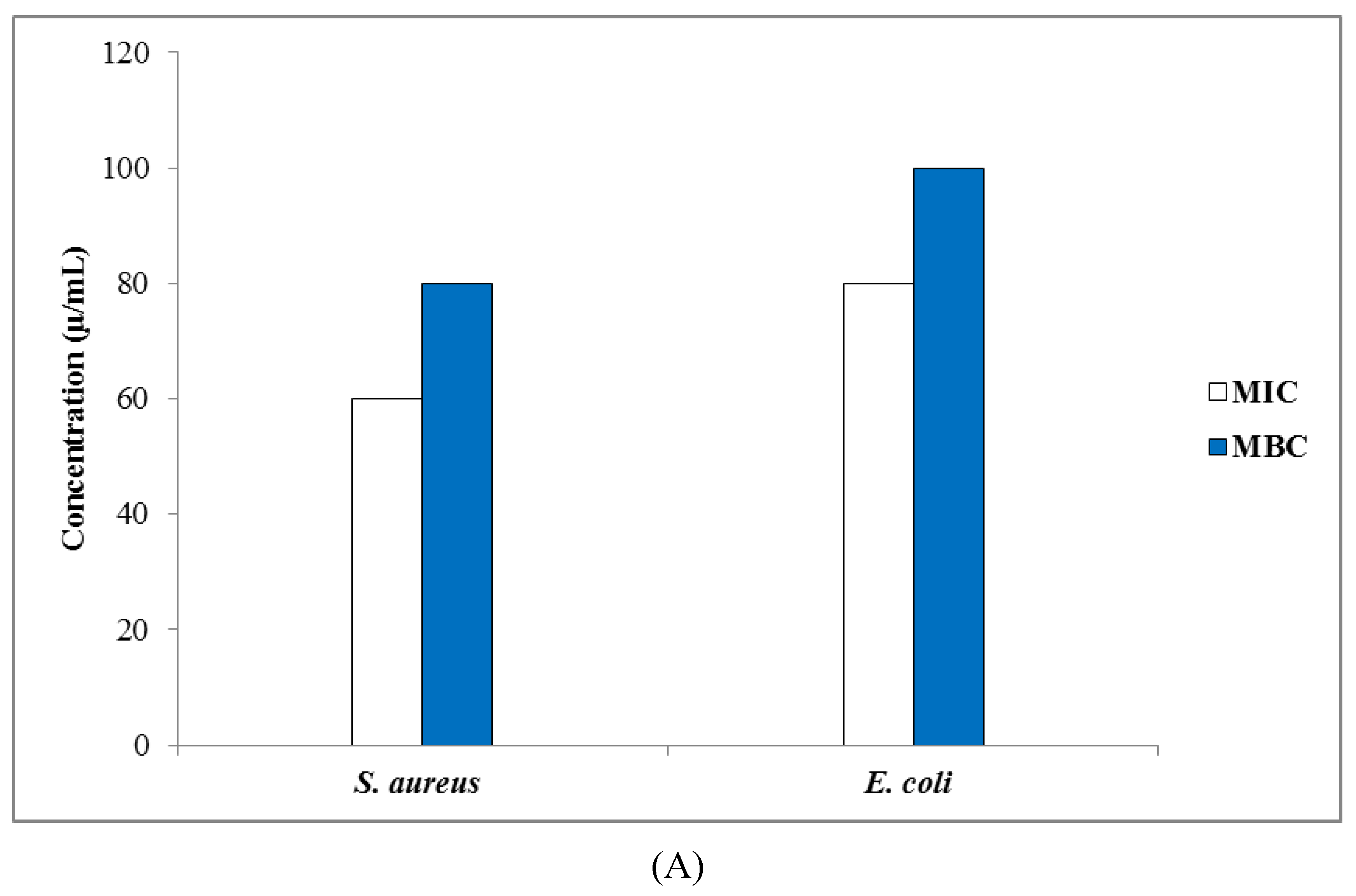

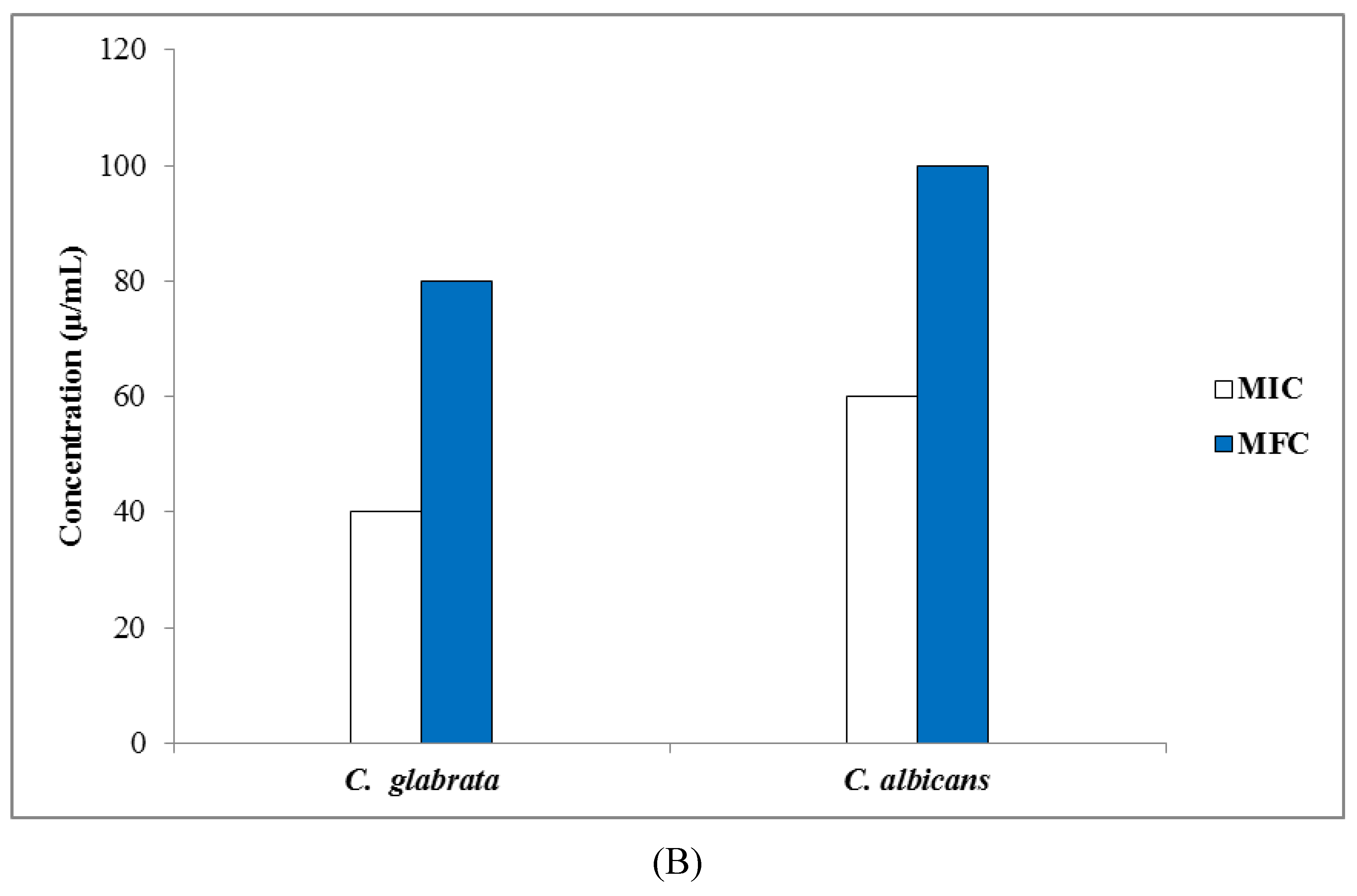

3.3.2. Determination of MIC, MBC, and MFC Values

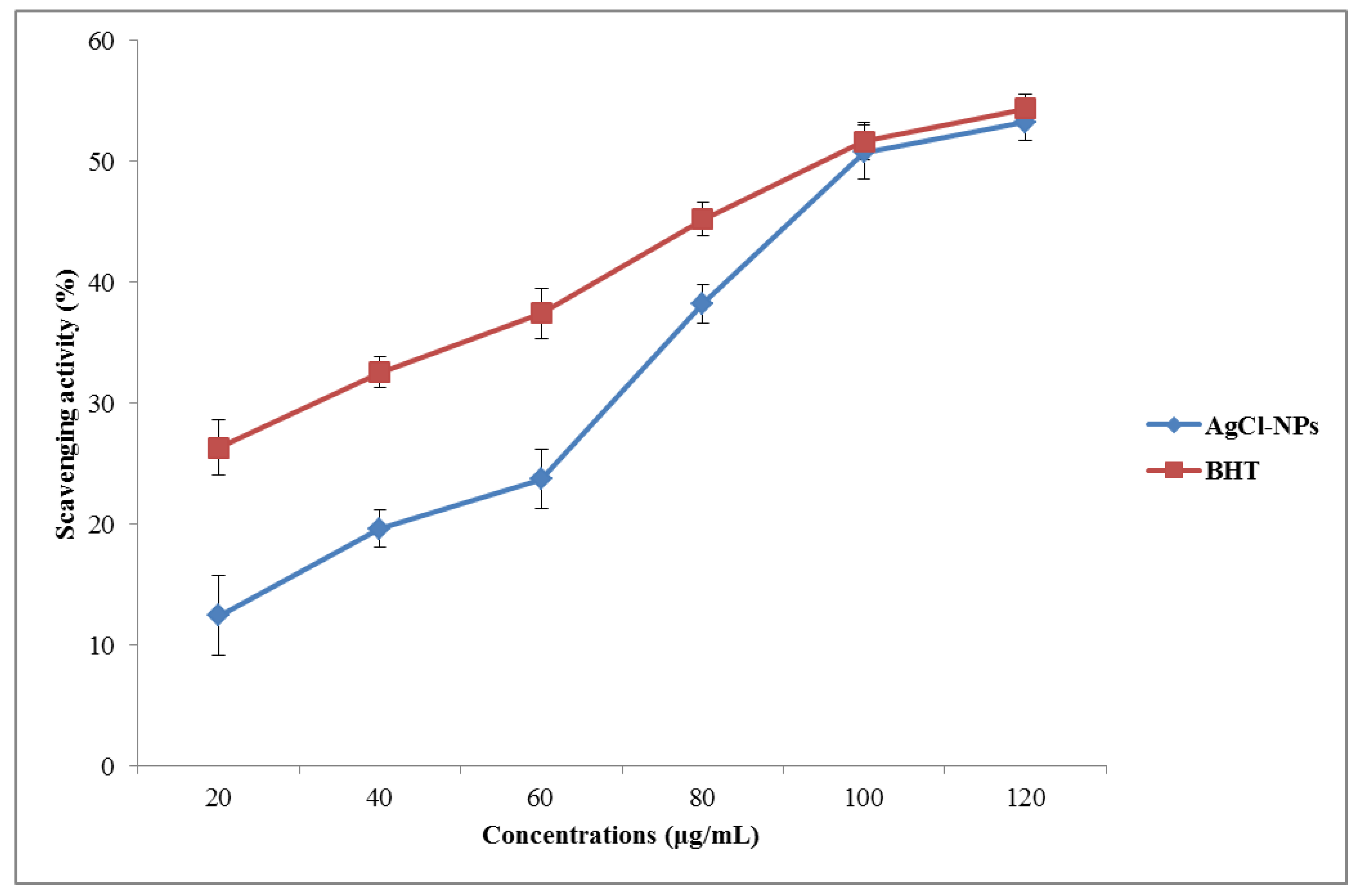

3.4. Antioxidant Properties of Biosynthesized AgCl-NPs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manivasagan, P.; Kim, S.K. Marine Algae Extracts: Processes, Products, and Applications; Kwon Kim, S., Chojnacka, K., Eds.; Wiley: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Roduner, E. Size matters: Why nanomaterials are different. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushing, B.L.; Kolesnichenko, V.L.; O’Connor, C.J. Recent advances in the liquid-phase syntheses of inorganic nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3893–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Fawcett, D.; Sharma, S.; Tripathy, S.K.; Poinern, G.E.J. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles via biological entities. Materials 2015, 8, 7278–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, V.; Bhargava, A.; Gupta, R.; Navin, J.; Jitendra, P. Synthesis and applications of noble metal nanoparticles: A review. Adv. Sci. Eng. Med. 2017, 9, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Biazar, E.; Jafarpour, M.; Montazeri, M.; Majdi, A.; Aminifard, S.; Zafari, M.; Akbari, H.R.; Rad, H.G. Nanotoxicology and nanoparticle safety in biomedical designs. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Gowramma, B.; Keerthi, U.; Mokula, R.; Rao, D.M. Biogenic silver nanoparticles production and characterization from native stain of Corynebacterium species and its antimicrobial activity. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gour, A.; Jain, N.K. Advances in green synthesis of nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirovetz, L.; Buchbauer, G.; Shafi, M.P.; Leela, N.K. Analysis of the essential oils of the leaves, stems, rhizomes and roots of the medicinal plant Alpinia galanga from southern India. Acta. Pharm. 2003, 53, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prakash, P.; Gnanaprakasam, P.; Emmanuel, R.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Saravanan, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Mimusops elengi, Linn. for enhanced antibacterial activity against multi drug resistant clinical isolates. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 108, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okaiyeto, K.; Ojemaye, M.O.; Hoppe, H.; Mabinya, L.V.; Okoh, A.I. Phytofabrication of silver/silver chloride nanoparticles using aqueous leaf extract of Oedera genistifolia: Characterization and antibacterial potential. Molecules 2019, 24, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, R.; Xin, T.Z.; Gunasagaran, S.; Wei, T.F.X.; Yang, E.F.C.; Kumar, N.J.; Dhanaraj, S.A. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Mangosteen leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2011, 15, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J.K.; Baek, K.H. Green synthesis of silver chloride nanoparticles using Prunus persica L. outer peel extract and investigation of antibacterial, anticandidal, antioxidant potential. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2016, 9, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, M.; Hara, K.; Kudo, J. Bactericidal actions of a silver ion solution on Escherichia coli, studied by energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy and proteomic analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 7589–7593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aritonang, H.F.; Koleangan, H.; Wuntu, A.D. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of medicinal plants’ (Impatiens balsamina and Lantana camara) fresh leaves and analysis of antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Microbiol. 2019, 8642303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.M.; Mosleh, A.M.; Elghany, A.A.; Shams-Eldin, E.; Abu Serea, E.S.; Ali, S.A.; Shalan, A.E. Coated silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, cytotoxicity, and optical properties. RSC Adv. 2019, 35, 20118–20136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Yang, J.L.; Shi, Y.P. Phytochemicals and biological activities of Pulicaria Species. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, F.; Rustaiyan, A.; Larijani, K.; Nadimi, M.; Masoudi, S. Essential oil composition of Artemisia biennis willd. and Pulicaria undulata (L.) C.A. mey., two compositae herbs growing wild in Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, M.E.F.; Matsuda, H.; Nakamura, S.; Yabe, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Yoshikawa, M. Sesquiterpenes from an Egyptian herbal medicine, Pulicaria undulata, with inhibitory effects on nitric oxide production in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 60, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.A.; Jülich, W.D.; Kusnick, C.; Lindequist, U. Screening of Yemeni medicinal plants for antibacterial and cytotoxic activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 74, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kamali, H.H.; Yousif, M.O.; Ahmed, O.I.; Sabir, S.S. Phytochemical analysis of the essential oil from aerial parts of Pulicaria undulata (L.) Kostel from Sudan. Ethnobot. Leaflets 2009, 13, 467–471. [Google Scholar]

- Foudah, A.I.; Alam, A.; Soliman, G.A.; Salkini, M.A.; Ahmed, E.O.I.; Yusufoglu, H.S. Pharmacognostical, antioxidant and antimicrobial studies of aerial part of Pulicaria somalensis (Family: Asteraceae). Asian J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 9, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.A.A.; Sharopov, F.S.; Alhaj, M.; Hill, G.M.; Porzel, A.; Arnold, N.; Setzer, W.N.; Schmidt, J.; Wessjohann, L. Chemical composition and biological activity of essential oil from Pulicaria undulata from Yemen. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, G.; Patra, J.K.; Debnath, T.; Ansari, A.; Shin, H.S. Investigation of antioxidant, antibacterial, antidiabetic, and cytotoxicity potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized using the outer peel extract of Ananas comosus (L.). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherzade, G.; Tavakoli, M.M.; Namaei, M.H. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) wastages and its antibacterial activity against six bacteria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017, 7, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Eleventh Informational Supplement; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, Approved Standard M7-A6; National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Setzer, W.N.; Iriti, M. Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. essential oil: An alternative or complementary treatment for Leishmaniasis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilamová, Z.; Konvičková, Z.; Mikeš, P.; Holišová, V.; Mančík, P.; Dobročka, E.; Kratošová, G.; Seidlerová, J. Ag-AgCl nanoparticles fixation on electrospun PVA fibres: Technological concept and progress. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraimathi, K.L.; Sudha, V.; Lavanya, R.; Brindha, P. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Alternanthera sessilis (Linn.) extract and their antimicrobial, antioxidant activities. Coll. Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 102, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marslin, G.; Siram, K.; Maqbool, Q.; Selvakesavan, R.K.; Kruszka, D.; Kachlicki, P.; Franklin, G. Secondary Metabolites in the Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles. Materials 2018, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Mukherjee, P.; Senapati, S.; Mandal, D.; Khan, M.I.; Kumar, R. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2003, 28, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanavath, K.N.; Islam, M.S.; Bankupalli, S.; Bhargava, S.K.; Shah, K.; Parthasarathy, R. Experimental investigations on the effect of pyrolytic bio–oil during the liquefaction of Karanja Press Seed Cake. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4986–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, V.; Priyadarshini, S.; Priyadharsshini, N.M.; Pandian, K.; Velusamy, P. Biogenic synthesis of antibacterial silver chloride nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Cissus quadrangularis Linn. Mater. Lett. 2013, 91, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Tak, Y.K.; Song, J.M. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticles? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaraj, C.; Jagan, E.G.; Rajasekar, S.; Selvakumar, P.; Kalaichelvan, P.T.; Mohan, N. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Acalypha indica leaf extracts and its antibacterial activity against water borne pathogens. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerf. 2010, 76, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.V.; Borase, H.P.; Patil, C.D.; Salunke, B.K. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using latex from few euphorbian plants and their antimicrobial potential. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 167, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.C.; Wu, X.J.; Xu, J.; Wang, B.B.; Jiang, F.L.; Liu, Y. Ultra small silver nanoclusters: Highly efficient antibacterial activity and their mechanisms. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouay, B.L.; Stellacci, F. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: A surface science insight. Nanotoday 2015, 10, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Prabhune, A.; Perry, C.C. Antibiotic mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles with potent antimicrobial activity and their application in antimicrobial coatings. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 32, 6789–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salati, S.; Doudi, M.; Madani, M. The biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles by mango plant extract and its anti-Candida effects. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 2018, 5, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbathamizh, L.; Ponnu, T.M.; Mary, E.J. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer potential of Morinda pubescens synthesized silver nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 6, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.A.; Palanichamy, V.; Roopan, S.M. One step production of AgCl nanoparticles and its antioxidant and photo catalytic activity. Mat. Lett. 2015, 144, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, S.; Zarrabi, A.; Khaleghi, M.; Danaei, M.; Mozafari, M.R. Selective cytotoxicity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against the MCF-7 tumor cell line and their enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 8013–8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

15,

15,  30,

30,  60,

60,  90,

90,  150 and

150 and  210 min). Additionally, color changes of reaction mixtures are shown.

210 min). Additionally, color changes of reaction mixtures are shown.

15,

15,  30,

30,  60,

60,  90,

90,  150 and

150 and  210 min). Additionally, color changes of reaction mixtures are shown.

210 min). Additionally, color changes of reaction mixtures are shown.

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharifi-Rad, M.; Pohl, P. Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (AgCl-NPs) Using a Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Aerial Part Extract and Their Application as Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10040638

Sharifi-Rad M, Pohl P. Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (AgCl-NPs) Using a Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Aerial Part Extract and Their Application as Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents. Nanomaterials. 2020; 10(4):638. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10040638

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharifi-Rad, Majid, and Pawel Pohl. 2020. "Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (AgCl-NPs) Using a Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Aerial Part Extract and Their Application as Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents" Nanomaterials 10, no. 4: 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10040638

APA StyleSharifi-Rad, M., & Pohl, P. (2020). Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (AgCl-NPs) Using a Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Aerial Part Extract and Their Application as Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents. Nanomaterials, 10(4), 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10040638