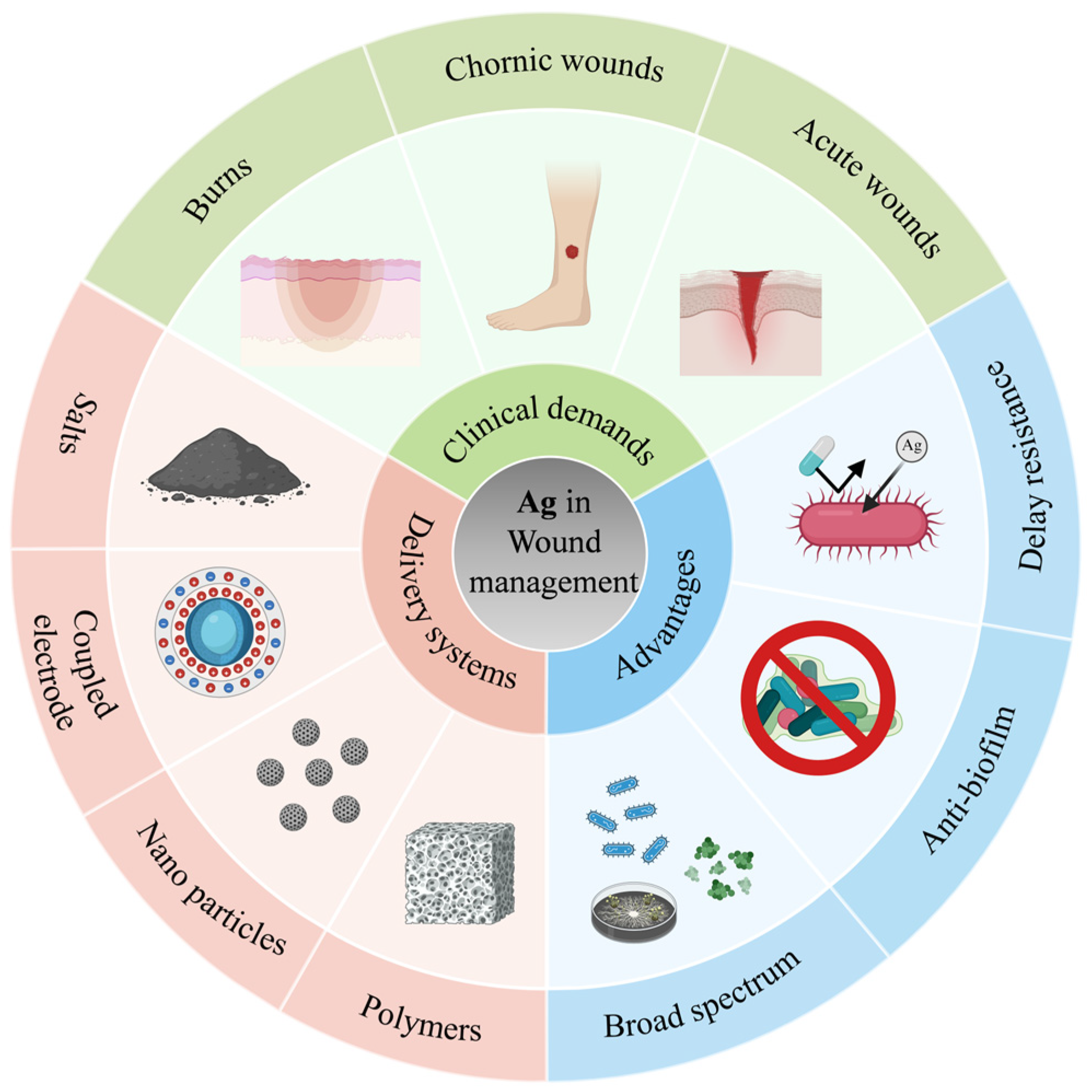

The Role of Silver and Silver-Based Products in Wound Management: A Review of Advances and Current Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

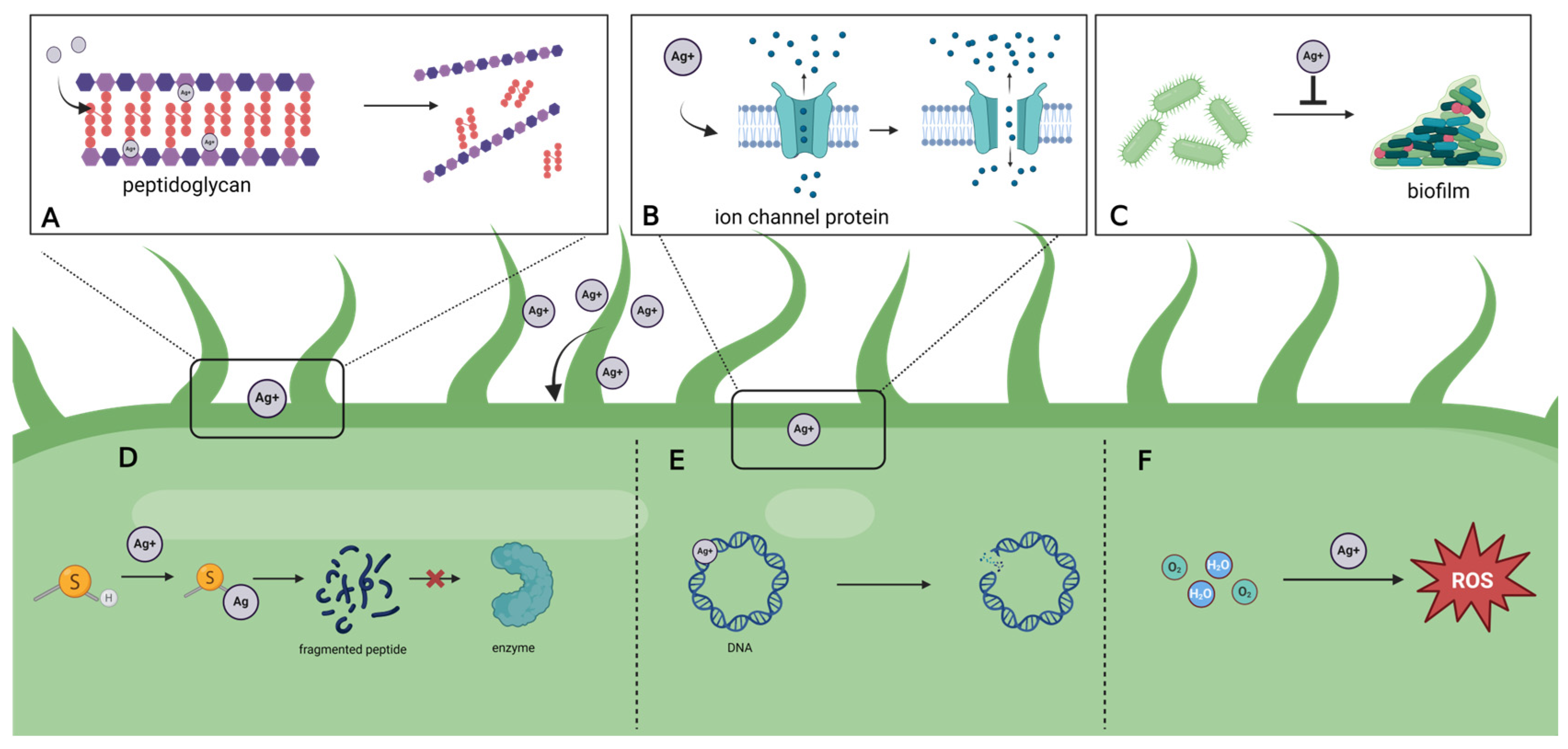

2. Antimicrobial Mechanism

2.1. Direct Effects

2.2. Indirect Effects

3. Delivery Systems

3.1. Silver Salts

3.2. Silver Coupled Electrodes

3.3. AgNP

3.3.1. Preparation Method

3.3.2. Modification

3.3.3. Clinical Application

3.4. Silver-Based Polymers

3.4.1. Synthesis Method

3.4.2. Multiple Biological Effects

3.4.3. Unique Physical and Chemical Properties

4. Current Clinical Application

4.1. Chronic Wound

4.2. Burns

4.3. Acute Wound

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.1.1. Toxicity

5.1.2. Instability

5.1.3. Drug Resistance

5.1.4. Lack of Clinical Evidence

| Number | Current Condition | Disease Categories | Treatments | Sample Size | Index | Conclusion | Last Update Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04582045 | Completed. | Acute wound-surgical infection. | Silver impregnated dressing—standard border wound bandage. | 1064 | Rate of postoperative infection within 30 days from surgery. | Unpublished. | 19 January 2023 |

| NCT02267122 | Completed. | Acute wound-surgical infection. | Ionic silver-containing dressing—Mupirocin ointment—Conventional dressing. | 147 | Rate of post operative infection within 30 days from surgery. | Topical application of mupirocin ointment achieves better results for the prevention of SSI than ionic silver-containing dressing or standard dressing in patients undergoing elective open colorectal surgery [134]. | 17 October 2014 |

| NCT02288884 | Completed. | Acute-surgical infection. | Silver containing dressing—Standard dressing. | 100 | Wound complication within 6 weeks. | Unpublished. | 13 October 2016 |

| NCT01143883 | Completed. | Acute-surgical infection. | Silverlon Dressing—Standard of Care Dressing. | 110 | Surgical Site Infection within 30 days. | Silver nylon is safe and effective in preventing surgical site infection following colorectal surgery [135]. | 13 June 2013 |

| NCT01229358 | Completed. | Acute-surgical infection. | Silver Eluting Dressing—Standard Gauze. | 500 | Wound complication rate within 30 days. | Under the study conditions, a silver-eluting alginate dressing showed no effect on the incidence of wound complications [136]. | 12 January 2016 |

| NCT00981110 | Completed. | Acute-surgical infection. | Mepore Self-adhesive absorbent dressing—AQUAGEL Ag Hydrofiber Wound Dressing. | 120 | The rate of patients with a Surgical site infection within 30 days. | This randomized trial did not confirm a statistically significant superiority of Aquacel Ag Hydrofiber dressing in reducing surgical-site infection after elective colorectal cancer surgery [101]. | 11 September 2012 |

| NCT01111695 | Completed. | Chronic wound—arterial or venous insufficiency. | Honey-ionic silver dressing. | 30 | Granulation and/or epithelial tissue progression. | Unpublished. | 30 September 2011 |

| NCT05009576 | Completed. | Chronic wound. | Vac with silver—simple VAC without silver alginate. | 62 | 1. Granulation tissue. 2. Size of wound. | Unpublished. | 17 August 2021 |

| NCT05667831 | Completed. | Chronic—Pressure Injury. | Alginate silver dressing—traditional dressing. | 160 | 1. Bacterial colony count. 2. White blood cell count. 3. High-sensitivity C- C-reactive protein. | Unpublished. | 29 December 2022 |

| NCT05824026 | Completed. | Burn. | Gelling fiber wound dressing with silver. | 52 | Percentage of wounds healed within 14 days. Complete healing is defined as ≥95% reepithelialization. | Unpublished. | 29 May 2024 |

| NCT01439074 | Completed. | Burn. | Mepilex Ag(Absorbent foam silver dressing)—Silver Sulphadiazine Ag cream. | 162 | Time to Healing. | Unpublished. | 18 December 2017 |

| NCT02108535 | Completed. | Burn. | Nanocrystalline silver—Silver Sulfadiazine. | 100 | Proportion of complete epithelialization of the wound. | No evidence of a difference between nanocrystalline silver and 1% silver sulfadiazine dressings regarding efficacy and safety outcomes [24]. | 18 May 2021 |

| NCT01553708 | Completed. | Burn. | Epidermal growth factor with silver sulfadiazine cream—Silver zinc sulfadiazine cream. | 34 | Time (days)for complete epithelialization. | Unpublished. | 25 March 2013 |

| NCT01598493 | Completed. | Burn. | Silver sulfadiazine cream—Activated carbon fiber impregnated with silver particles. | 30 | The healing rate, healing rate healed area/the number of healing days. | Unpublished. | 13 July 2017 |

| NCT02109718 | Completed. | Burn. | Open Dressings with Petrolatum Jelly—Silver Sulfadiazine Gauze Dressing Group. | 50 | 1. Number of days to complete re-epithelialization. 2. Incidence of wound infection. 3. Incidence of adverse reactions, including allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). | Petrolatum gel without top dressings may be at least as effective as silver sulfadiazine gauze dressings with regard to time to re-epithelialization, and incidence of infection and allergic contact dermatitis [137]. | 10 April 2014 |

5.2. Research Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barillo, D.J.; Marx, D.E. Silver in Medicine: A Brief History BC 335 to Present. Burns 2014, 40, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul Barkat, H.; Abul Barkat, M.; Ali, R.; Hadi, H.; Kasmuri, A.R. Old Wine in New Bottles: Silver Sulfadiazine Nanotherapeutics for Burn Wound Management. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2025, 24, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Jang, Y.-S. Preparation and Characterization of Activated Carbon Fibers Supported with Silver Metal for Antibacterial Behavior. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 261, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.-J.; Yi, S.-C.; Oh, S.-G. Preparation and Antibacterial Effects of Ag-SiO2 Thin Films by Sol-Gel Method. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4921–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, V.; Bechert, T.; Steinrücke, P.; Wagener, M.; Seidel, P.; Dingeldein, E.; Domann, E.; Schnettler, R. An in Vitro Assessment of the Antibacterial Properties and Cytotoxicity of Nanoparticulate Silver Bone Cement. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 4383–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X.; Xie, H. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Medical Applications and Biosafety. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8996–9031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catauro, M.; Raucci, M.G.; De Gaetano, F.; Marotta, A. Antibacterial and Bioactive Silver-Containing Na2O·CaO·2SiO2 Glass Prepared by Sol-Gel Method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyba, I.; Mui, B.B.-K.; Bau, R.; Noguchi, R.; Nomiya, K. Synthesis and Structure of a Water-Soluble Hexanuclear Silver(I) Nicotinate Cluster Comprised of a “Cyclohexane-Chair”-Type of Framework, Showing Effective Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities: Use of “Sparse Matrix” Techniques for Growing Crystals of Water-Soluble Inorganic Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 8028–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Gameros, L.; Chevallier, P.; Sarkissian, A.; Mantovani, D. Silver-Based Antibacterial Strategies for Healthcare-Associated Infections: Processes, Challenges, and Regulations. An Integrated Review. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2020, 24, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, M.Y.M.; Medema, G.; van Halem, D. Enhanced Virus Inactivation by Copper and Silver Ions in the Presence of Natural Organic Matter in Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 882, 163614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Y.; Chen, X.; Ahmed, T.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y. Toxicity and Action Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles against the Mycotoxin-Producing Fungus Fusarium Graminearum. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panáček, A.; Kvítek, L.; Smékalová, M.; Večeřová, R.; Kolář, M.; Röderová, M.; Dyčka, F.; Šebela, M.; Prucek, R.; Tomanec, O.; et al. Bacterial Resistance to Silver Nanoparticles and How to Overcome It. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smekalova, M.; Aragon, V.; Panacek, A.; Prucek, R.; Zboril, R.; Kvitek, L. Enhanced Antibacterial Effect of Antibiotics in Combination with Silver Nanoparticles against Animal Pathogens. Vet. J. 1997, 209, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, M.; Lee, D.G. Silver Nanoparticles Against Salmonella Enterica Serotype Typhimurium: Role of Inner Membrane Dysfunction. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 74, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezza, F.A.; Tichapondwa, S.M.; Chirwa, E.M.N. Synthesis of Biosurfactant Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles, Characterization and Their Potential Application for Bactericidal Purposes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wee, C.Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, W.E.J.; Thian, E.S. Silver-Substituted Hydroxyapatite Inhibits Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Outer Membrane Protein F: A Potential Antibacterial Mechanism. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 134, 112713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, R.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Qin, Y. Potential Antibacterial Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles and the Optimization of Orthopedic Implants by Advanced Modification Technologies. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 3311–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoon, A.A.; Khadka, P.; Freeland, J.; Gundampati, R.K.; Manso, R.H.; Ruiz, M.; Krishnamurthi, V.R.; Thallapuranam, S.K.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Silver Ions Caused Faster Diffusive Dynamics of Histone-Like Nucleoid-Structuring Proteins in Live Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02479-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelGawwad, M.R.; Mahmutović, E.; Al Farraj, D.A.; Elshikh, M.S. In Silico Prediction of Silver Nitrate Nanoparticles and Nitrate Reductase A (NAR A) Interaction in the Treatment of Infectious Disease Causing Clinical Strains of E. Coli. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1580–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhu, F.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Dai, G.; Wu, G.; Wang, L.; et al. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles against Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M.J.; Kang, K.A.; Lee, I.K.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Choi, J.; Hyun, J.W. Silver Nanoparticles Induce Oxidative Cell Damage in Human Liver Cells through Inhibition of Reduced Glutathione and Induction of Mitochondria-Involved Apoptosis. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 201, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulaz, S.; Vitale, S.; Quinn, L.; Casey, E. Nanoparticle-Biofilm Interactions: The Role of the EPS Matrix. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S.S.I.; Katas, H.; Azmi, F.; Busra, M.F.M. Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Biosynthesised Silver and Gold Nanoparticles for Medical Applications: Mechanism of Action, Toxicity and Current Status. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, S.S.; de Camargo, M.C.; Caetano, R.; Alves, M.R.; Itria, A.; Pereira, T.V.; Lopes, L.C. Efficacy and Costs of Nanocrystalline Silver Dressings versus 1% Silver Sulfadiazine Dressings to Treat Burns in Adults in the Outpatient Setting: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Burns 2022, 48, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bi, Z.; Hu, Y.; Sun, L.; Song, Y.; Chen, S.; Mo, F.; Yang, J.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Silver Nanoparticles and Silver Ions Cause Inflammatory Response through Induction of Cell Necrosis and the Release of Mitochondria in Vivo and in Vitro. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2021, 37, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Xiao, S.; Xia, Z. Chinese Burn Association Tissue Repair of Burns and Trauma Committee; Cross-Straits Medicine Exchange Association of China. Consensus on the Treatment of Second-Degree Burn Wounds (2024 Edition). Burn. Trauma 2024, 12, tkad061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, L.D.S.; Almeida, J.C.D.A.; Passoni, L.C.; Gossani, C.M.D.; Taveira, G.B.; Gomes, V.M.; Vieira-Da-Motta, O. Antifungal Activity of Silver Salts of Keggin-Type Heteropolyacids against Sporothrix spp. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Ellis, B.; Lam, K.; Johnson, F.; Khoury, A.E. Mechanism of Electrical Enhancement of Efficacy of Antibiotics in Killing Biofilm Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 2803–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.; Fernandes, M.M.; Carvalho, E.O.; Nicolau, A.; Lazic, V.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Exploring Electroactive Microenvironments in Polymer-Based Nanocomposites to Sensitize Bacterial Cells to Low-Dose Embedded Silver Nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2022, 139, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Carretero, S.; Nybom, R.; Richter-Dahlfors, A. Electroenhanced Antimicrobial Coating Based on Conjugated Polymers with Covalently Coupled Silver Nanoparticles Prevents Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilm Formation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1700435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.K.; Nuutila, K.; Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Diaz, V.; Anselmo, K.; Batchinsky, M.; Carlsson, A.; Ghosh, N.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Study to Evaluate the Effectiveness of a Fabric-Based Wireless Electroceutical Dressing Compared to Standard-of-Care Treatment Against Acute Trauma and Burn Wound Biofilm Infection. Adv. Wound Care 2024, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhong, L.; Xue, J. Preparation and Properties of Conductive Bacterial Cellulose-Based Graphene Oxide-Silver Nanoparticles Antibacterial Dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 257, 117671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, I.X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, I.S.; Mei, M.L.; Li, Q.; Chu, C.H. The Antibacterial Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles and Its Application in Dentistry. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Chuan, J.-L.; Zhao, G.-P.; Fu, Q. Construction of Silver-Coated High Translucent Zirconia Implanting Abutment Material and Its Property of Antibacterial. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, A.; Liakopoulou, A.; Papoulis, D.; Gianni, E.; Gkolfi, P.; Zygouri, E.; Letsiou, S.; Hatziantoniou, S. Effect of Peptides on the Synthesis, Properties and Wound Healing Capacity of Silver Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strużyńska, L.; Skalska, J. Mechanisms Underlying Neurotoxicity of Silver Nanoparticles. In Cellular and Molecular Toxicology of Nanoparticles; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018; Volume 1048, pp. 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Characteristics and Biocompatibility of the Surgical Sutures Coated with Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles—PubMeD. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30716622/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Panáček, D.; Hochvaldová, L.; Bakandritsos, A.; Malina, T.; Langer, M.; Belza, J.; Martincová, J.; Večeřová, R.; Lazar, P.; Poláková, K.; et al. Silver Covalently Bound to Cyanographene Overcomes Bacterial Resistance to Silver Nanoparticles and Antibiotics. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudillat, Q.; Kirchhoff, J.-L.; Jourdain, I.; Humblot, V.; Figarol, A.; Knorr, M.; Strohmann, C.; Viau, L. Coordination Assemblies of Acetylenic Dithioether Ligands on Silver(I) Salts: Crystal Structure, Antibacterial and Cytotoxicity Activities. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 19249–19265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Ge, Y.; Wang, F. Silver Nanoparticle-Anchored Human Hair Kerateine/PEO/PVA Nanofibers for Antibacterial Application and Cell Proliferation. Molecules 2021, 26, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, M.K.; Doll, K.; Rahim, M.I.; Mikolai, C.; Winkel, A.; Stiesch, M. Antibacterial and Cytocompatible: Combining Silver Nitrate with Strontium Acetate Increases the Therapeutic Window. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pormohammad, A.; Greening, D.; Turner, R.J. Synergism Inhibition and Eradication Activity of Silver Nitrate/Potassium Tellurite Combination against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pormohammad, A.; Firrincieli, A.; Salazar-Alemán, D.A.; Mohammadi, M.; Hansen, D.; Cappelletti, M.; Zannoni, D.; Zarei, M.; Turner, R.J. Insights into the Synergistic Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nitrate with Potassium Tellurite against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0062823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.; Lo, J.; Hsu, E.; Burt, H.M.; Shademani, A.; Lange, D. The Combined Use of Gentamicin and Silver Nitrate in Bone Cement for a Synergistic and Extended Antibiotic Action against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Materials 2021, 14, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikhao, N.; Ounkaew, A.; Srichiangsa, N.; Phanthanawiboon, S.; Boonmars, T.; Artchayasawat, A.; Theerakulpisut, S.; Okhawilai, M.; Kasemsiri, P. Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticle Coating on Paper for Antibacterial and Antiviral Applications. Polym. Bull. 2022, 80, 9651–9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussin, J.; Robles-Botero, V.; Casañas-Pimentel, R.; Rojas, F.; Angiolella, L.; San Martín-Martínez, E.; Giusiano, G. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity of Green Synthesis Silver Nanoparticles Targeting Skin and Soft Tissue Infectious Agents. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, P.; Kacharaju, K.R.; Anumala, N.; Pathakota, K.R.; Avula, J. Application of Bioelectric Effect to Reduce the Antibiotic Resistance of Subgingival Plaque Biofilm: An in Vitro Study. J. Indian. Soc. Periodontol. 2018, 22, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttasattakrit, K.; Khamkeaw, A.; Tangwongsan, C.; Pavasant, P.; Phisalaphong, M. Ionic Silver and Electrical Treatment for Susceptibility and Disinfection of Escherichia Coli Biofilm-Contaminated Titanium Surface. Molecules 2021, 27, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baś, B.; Jakubowska, M. The Renovated Silver Ring Electrode in Determination of Lead Traces by Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 615, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldiren, D.; Aydın, S. Antimicrobial Property of Silver, Silver-Zinc and Silver-Copper Incorporated Soda Lime Glass Prepared by Ion Exchange. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 78, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.J.; Faustman, E.M. Silver Nanoparticle (AgNP), Neurotoxicity, and Putative Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP): A Review. Neurotoxicology 2025, 108, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; He, B.; Liu, L.; Qu, G.; Shi, J.; Hu, L.; Jiang, G. Antibacterial Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Proteomics Approach. Metallomics 2018, 10, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Kanwal, Z.; Rauf, A.; Sabri, A.N.; Riaz, S.; Naseem, S. Size- and Shape-Dependent Antibacterial Studies of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Wet Chemical Routes. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, S.; Verma, S.K.; Hemlata; Azam, M.; Sardar, M.; Haq, Q.M.R.; Fatma, T. Antibacterial Efficacy of Facile Cyanobacterial Silver Nanoparticles Inferred by Antioxidant Mechanism. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 122, 111888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.-M.; Hsu, J.-H.; Shih, M.-K.; Hsieh, C.-W.; Ju, W.-J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Lee, B.-H.; Hou, C.-Y. Process Optimization of Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis and Its Application in Mercury Detection. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanadhas, D.P.; Ben Thomas, M.; Thomas, R.; Raichur, A.M.; Chakravortty, D. Interaction of Silver Nanoparticles with Serum Proteins Affects Their Antimicrobial Activity in Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4945–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver Nanoparticle Protein Corona and Toxicity: A Mini-Review—PubMeD. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26337542/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Patil, M.P.; Kim, G.-D. Eco-Friendly Approach for Nanoparticles Synthesis and Mechanism behind Antibacterial Activity of Silver and Anticancer Activity of Gold Nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldakheel, F.M.; Mohsen, D.; El Sayed, M.M.; Alawam, K.A.; Binshaya, A.S.; Alduraywish, S.A. Silver Nanoparticles Loaded on Chitosan-g-PVA Hydrogel for the Wound-Healing Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Kumar, D.; Agrawal, V. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Indian Belladonna Extract and Their Potential Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Anticancer and Larvicidal Activities. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Cha, S.-H.; Cho, S.; Park, Y. Tannic Acid-Mediated Green Synthesis of Antibacterial Silver Nanoparticles. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2016, 39, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, L.; Riaz Rajoka, M.S.; Yan, L.; Jiang, C.; Shao, D.; Zhu, J.; Shi, J.; Huang, Q.; Yang, H.; et al. Fungal Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Application and Challenges. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, M.T.; Zayed, M.; Salama, H.S. Antibacterial Potential of Bacterial Cellulose Impregnated with Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticle Against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez Miranda, M.; Liu, W.; Godinez-Leon, J.A.; Amanova, A.; Houel-Renault, L.; Lampre, I.; Remita, H.; Gref, R. Colloidal Silver Nanoparticles Obtained via Radiolysis: Synthesis Optimization and Antibacterial Properties. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Santiago, I.; Foord, J. High-Yield Electrochemical Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Enzyme-Modified Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Langmuir 2020, 36, 6089–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, V.A.; Jimenez-Villar, E.; da Silva Filho, J.M.C.; Yassitepe, E.; Mogili, N.V.V.; Iikawa, F.; de Sá, G.F.; Cesar, C.L.; Marques, F.C. Size Control of Silver-Core/Silica-Shell Nanoparticles Fabricated by Laser-Ablation-Assisted Chemical Reduction. Langmuir 2017, 33, 2257–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Saito, S.; Kita, R.; Jang, J.; Choi, Y.; Choi, J.; Okochi, M. Array-Based Screening of Silver Nanoparticle Mineralization Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, G.; Kubo, A.-L.; Vija, H.; Kahru, A.; Bondar, D.; Karpichev, Y.; Bondarenko, O. Synergistic Antibacterial Effect of Copper and Silver Nanoparticles and Their Mechanism of Action. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wang, M.; Cheng, L.; Si, M.; Feng, Z.; Feng, Z. Synergistic Antibacterial Mechanism of Silver-Copper Bimetallic Nanoparticles. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1337543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, N.; Ermenlieva, N.; Simeonova, L.; Kolev, I.; Slavov, I.; Karashanova, D.; Andonova, V. Chlorhexidine-Silver Nanoparticle Conjugation Leading to Antimicrobial Synergism but Enhanced Cytotoxicity. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, R.; Maiti, P.K.; Murmu, N.; Datta, A. Preparation of Serum Capped Silver Nanoparticles for Selective Killing of Microbial Cells Sparing Host Cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madiwal, V.; Rajwade, J. Silver-Deposited Titanium as a Prophylactic “nano Coat” for Peri-Implantitis. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokabber, T.; Cao, H.T.; Norouzi, N.; van Rijn, P.; Pei, Y.T. Antimicrobial Electrodeposited Silver-Containing Calcium Phosphate Coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 5531–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, K. State-of-the-Art Surfactant-Based Coatings for Biomaterials: Innovations, Applications, and Future Prospects in Biomedical Engineering. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 681, 125879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissel, F.J.; Platania, V.; Tsikourkitoudi, V.; Larsson, J.V.; Thersleff, T.; Chatzinikolaidou, M.; Sotiriou, G.A. Silver/Gold Nanoalloy Implant Coatings with Antibiofilm Activity via pH-Triggered Silver Ion Release. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 7729–7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Mondal, S.; Ojha, N.; Sahoo, S.; Zeyad, M.T.; Kumar, S.; Sarma, D. Self-Template Impregnated Silver Nanoparticles in Coordination Polymer Gel: Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction, CO2 Fixation, and Antibacterial Activity. Nanoscale 2024, 17, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, L.P.; Dutta, D.; Mukherjee, R.; Das, T.K.; Biswas, S. Polyoxometalate-Polymer Directed Macromolecular Architectonics of Silver Nanoparticles as Effective Antimicrobials. Chem. Asian J. 2024, 19, e202400344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiriani, T.; Shaabani, A. Pectin-Based Magnetic Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Cross-Linked via the Betti Reaction and Decorated by Silver NPs (Fe3O4@MIP/Ag): A Safe and Potential Antibacterial Nano-Carrier for Highly Sustained Release of Tetracycline. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, C.C.S.; Panico, K.; Trousil, J.; Janoušková, O.; de Castro, C.E.; Štěpánek, P.; Giacomelli, F.C. Protein Coronas Coating Polymer-Stabilized Silver Nanocolloids Attenuate Cytotoxicity with Minor Effects on Antimicrobial Performance. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 218, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Hajizadeh, S.; Liu, W.; Ye, L. Imprinted Polymer Beads Loaded with Silver Nanoparticles for Antibacterial Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 2829–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.; Kaimlová, M.; Vyhnálková, B.; Trelin, A.; Lyutakov, O.; Slepička, P.; Švorčík, V.; Veselý, M.; Vokatá, B.; Malinský, P.; et al. Optomechanical Processing of Silver Colloids: New Generation of Nanoparticle-Polymer Composites with Bactericidal Effect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erol, I.; Cigerci, I.H.; Özkara, A.; Akyıl, D.; Aksu, M. Synthesis of Moringa Oleifera Coated Silver-Containing Nanocomposites of a New Methacrylate Polymer Having Pendant Fluoroarylketone by Hydrothermal Technique and Investigation of Thermal, Optical, Dielectric and Biological Properties. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2022, 33, 1231–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Barman, S.; Haldar, J. Engineering Antimicrobial Polymer Nanocomposites: In Situ Synthesis, Disruption of Polymicrobial Biofilms, and In Vivo Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 34527–34537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymer-Assisted In Situ Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) Impregnated Wound Patch Potentiate Controlled Inflammatory Responses for Brisk Wound Healing—PubMeD. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31849472/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Xu, L.; Xia, C.; Gan, L. High Performance Flexible and Antibacterial Strain Sensor Based on Silver-carbon Nanotubes Coated Cellulose/Polyurethane Nanofibrous Membrane: Cellulose as Reinforcing Polymer Blend and Polydopamine as Compatibilizer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3D-Printed Polymer-Infiltrated Ceramic Network with Antibacterial Biobased Silver Nanoparticles—PubMeD. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36166595/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for the Fabrication of Non Cytotoxic and Antibacterial Metallic Polymer Based Nanocomposite System—PubMeD. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34006995/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Naapuri, J.M.; Losada-Garcia, N.; Deska, J.; Palomo, J.M. Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles-Enzyme-Polymer Conjugate Hybrids as Dual-Activity Catalysts for Chemoenzymatic Cascade Reactions. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 5701–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, M.; Noruzi, E.B.; Sheykhsaran, E.; Ebadi, B.; Kariminezhad, Z.; Molaparast, M.; Mehrabani, M.G.; Mehramouz, B.; Yousefi, M.; Ahmadi, R.; et al. Carbohydrate Polymer-Based Silver Nanocomposites: Recent Progress in the Antimicrobial Wound Dressings. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 231, 115696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, A.; Virych, P.; Myasoyedov, V.; Prokopiuk, V.; Onishchenko, A.; Butov, D.; Kuziv, Y.; Yeshchenko, O.; Zhong, S.; Nie, G.; et al. Cytotoxicity of Hybrid Noble Metal-Polymer Composites. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1487024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bańkosz, M.; Tyliszczak, B. Investigation of Silver- and Plant Extract-Infused Polymer Systems: Antioxidant Properties and Kinetic Release. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, D.R.; Lima, G.A.S.; de Oliveira, H.P.M.; Pellosi, D.S. Pluronic-Loaded Silver Nanoparticles/Photosensitizers Nanohybrids: Influence of the Polymer Chain Length on Metal-Enhanced Photophysical Properties. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fesseha, Y.A.; Manayia, A.H.; Liu, P.-C.; Su, T.-H.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chiu, C.-W.; Cheng, C.-C. Photoreactive Silver-Containing Supramolecular Polymers That Form Self-Assembled Nanogels for Efficient Antibacterial Treatment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 654, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissemond, J.; Böttrich, J.G.; Braunwarth, H.; Hilt, J.; Wilken, P.; Münter, K.-C. Evidence for Silver in Wound Care—Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies from 2000–2015. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2017, 15, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.G.; Higham, C.; Broussard, K.; Phillips, T.J. Wound Healing and Treating Wounds: Chronic Wound Care and Management. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.; Dickson, W.A.; Boyce, D.E. Burns. BMJ 2006, 332, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olutoye, O.O.; Eriksson, E.; Menchaca, A.D.; Kirsner, R.S.; Tanaka, R.; Schultz, G.; Weir, D.; Wagner, T.L.; Fabia, R.B.; Naik-Mathuria, B.; et al. Management of Acute Wounds-Expert Panel Consensus Statement. Adv. Wound Care 2024, 13, 553–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, D.; Tan, L.; Huang, H. Silver Dressings for the Healing of Venous Leg Ulcer: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Medicine 2020, 99, e22164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, F. Analysis of Therapeutic Effect of Silver-Based Dressings on Chronic Wound Healing. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazareth, I.; Meaume, S.; Sigal-Grinberg, M.L.; Combemale, P.; Le Guyadec, T.; Zagnoli, A.; Perrot, J.L.; Sauvadet, A.; Bohbot, S. Efficacy of a Silver Lipidocolloid Dressing on Heavily Colonised Wounds: A Republished RCT. J. Wound Care 2012, 21, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, R.; Fattori, L.; Bertani, E.; Radice, D.; Rotmensz, N.; Misitano, P.; Cenciarelli, S.; Chiappa, A.; Tadini, L.; Mancini, M.; et al. Surgical Site Infections Following Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Randomized Prospective Trial Comparing Common and Advanced Antimicrobial Dressing Containing Ionic Silver. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound Healing: Cellular Mechanisms and Pathological Outcomes. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Kirsner, R. Pathophysiology of Acute Wound Healing. Clin. Dermatol. 2007, 25, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressings and Topical Agents for Treating Venous Leg Ulcers—PubMeD. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29906322/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Stryja, J.; Teplá, K.; Routek, M.; Pavlík, V.; Perutková, D. Octenidine with Hyaluronan Dressing versus a Silver Dressing in Hard-to-Heal Wounds: A Post-Marketing Study. J. Wound Care 2023, 32, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasowski, G.; Jawień, A.; Tukiendorf, A.; Rybak, Z.; Junka, A.; Olejniczak-Nowakowska, M.; Bartoszewicz, M.; Smutnicka, D. A Comparison of an Antibacterial Sandwich Dressing vs Dressing Containing Silver. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Martín, L.C.; García-Martínez, L.; Román-Curto, C.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.V.; Suárez-Fernández, R.M. Negative Pressure and Nanocrystalline Silver Dressings for Nonhealing Ulcer: A Randomized Pilot Study. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosti, G.; Magliaro, A.; Mattaliano, V.; Picerni, P.; Angelotti, N. Comparative Study of Two Antimicrobial Dressings in Infected Leg Ulcers: A Pilot Study. J. Wound Care 2015, 24, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Gálvez, J.; Martínez-Isasi, S.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Rumbo-Prieto, J.M.; Sobrido-Prieto, M.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.; García-Martínez, M.; Fernández-García, D. Cytotoxicity and Concentration of Silver Ions Released from Dressings in the Treatment of Infected Wounds: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1331753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine, N.; Jolley, J.; Kyi, M.; King, S.; Iacobaccio, L.; Staunton, E.; Wilson, B.; Seymour, C.; Rogasch, S.; Wraight, P. Prospective Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Silver Dressings to Enhance Healing of Acute Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcers. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, S.; James, G.A.; Goeres, D.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Vickery, K.; Percival, S.L.; Stoodley, P.; Schultz, G.; Jensen, S.O.; Malone, M. The Efficacy of Topical Agents Used in Wounds for Managing Chronic Biofilm Infections: A Systematic Review. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khansa, I.; Schoenbrunner, A.R.; Kraft, C.T.; Janis, J.E. Silver in Wound Care-Friend or Foe?: A Comprehensive Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyneman, A.; Hoeksema, H.; Vandekerckhove, D.; Pirayesh, A.; Monstrey, S. The Role of Silver Sulphadiazine in the Conservative Treatment of Partial Thickness Burn Wounds: A Systematic Review. Burns 2016, 42, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Välimäki, M.; Zhou, Q.; Dai, W.; Guo, J. Effectiveness of Silver and Iodine Dressings on Wound Healing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Yao, H.-J.; Wang, Y. Effect of Silver-Containing Hydrofiber Dressing on Burn Wound Healing: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee Kee, E.; Stockton, K.; Kimble, R.M.; Cuttle, L.; McPhail, S.M. Cost-Effectiveness of Silver Dressings for Paediatric Partial Thickness Burns: An Economic Evaluation from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Burns 2017, 43, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; He, X.; Hou, A. Meta-Analysis of the Therapeutic Effect of Nanosilver on Burned Skin. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 7730–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nherera, L.; Trueman, P.; Roberts, C.; Berg, L. Silver Delivery Approaches in the Management of Partial Thickness Burns: A Systematic Review and Indirect Treatment Comparison. Wound Repair Regen. 2017, 25, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Kou, Y.; Hu, A. Efficacy and Safety of Nano-Silver Dressings Combined with Recombinant Human Epidermal Growth Factor for Deep Second-Degree Burns: A Meta-Analysis. Burns 2021, 47, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, T.; Ousey, K.; Haesler, E.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Carville, K.; Idensohn, P.; Kalan, L.; Keast, D.H.; Larsen, D.; Percival, S.; et al. IWII Wound Infection in Clinical Practice Consensus Document: 2022 Update. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, S10–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumville, J.C.; Gray, T.A.; Walter, C.J.; Sharp, C.A.; Page, T.; Macefield, R.; Blencowe, N.; Milne, T.K.; Reeves, B.C.; Blazeby, J. Dressings for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD003091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, Z.; Said, S.M.; Mohammad, W.A.; Aboulnasr, G.N.; Elshimy, N.A. Silver-Nanoparticle- and Silver-Nitrate-Induced Antioxidant Disbalance, Molecular Damage, and Histochemical Change on the Land Slug (Lehmannia Nyctelia) Using Multibiomarkers. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 945776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamasinoro, S.N.; Dieme, D.; Haddad, S.; Bouchard, M. Toxicokinetics of Silver Element Following Inhalation of Silver Nitrate in Rats. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Riviere, J.E. Pharmacokinetics of Metallic Nanoparticles. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Niu, S.; Shang, M.; Li, J.; Guo, M.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Shen, X.; et al. ROS-Drp1-Mediated Mitochondria Fission Contributes to Hippocampal HT22 Cell Apoptosis Induced by Silver Nanoparticles. Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, W.; Hileuskaya, K.; Shao, P. Oriented Structure Design of Pectin/Ag Nanosheets Film with Improved Barrier and Long-Term Antimicrobial Properties for Edible Fungi Preservation. Food Chem. 2025, 484, 144451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, S.; Scalia, A.C.; Nascimben, M.; Perero, S.; Rimondini, L.; Spriano, S.; Cochis, A. Bacteriostatic, Silver-Doped, Zirconia-Based Thin Coatings for Temporary Fixation Devices Tuning Stem Cells’ Expression of Adhesion-Relevant Genes and Proteins. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 176, 214360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wei, S.; He, N.; Shen, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, H.; Kang, X.; Cai, Y.; Ye, Y.; Li, P.; et al. Photo-Enhanced Synergistic Sterilization and Self-Regulated Ion Release in rGO-Ag Nanocomposites under NIR Irradiation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 253, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabryla, L.M.; Johnston, K.A.; Diemler, N.A.; Cooper, V.S.; Millstone, J.E.; Haig, S.-J.; Gilbertson, L.M. Role of Bacterial Motility in Differential Resistance Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles and Silver Ions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, H. Mechanisms of Bacterial Resistance to Environmental Silver and Antimicrobial Strategies for Silver: A Review. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundeshagen, G.; Collins, V.N.; Wurzer, P.; Sherman, W.; Voigt, C.D.; Cambiaso-Daniel, J.; Nunez Lopez, O.; Sheaffer, J.; Herndon, D.N.; Finnerty, C.C.; et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial Comparing the Outpatient Treatment of Pediatric and Adult Partial-Thickness Burns with Suprathel or Mepilex Ag. J. Burn. Care Res. 2018, 39, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwala, S.; Harish, V.; Roberts, S.; Brady, M.; Lajevardi, S.; Doherty, J.; D’Souza, M.; Haertsch, P.A.; Maitz, P.K.M.; Issler-Fisher, A.C. Treatment of Partial Thickness Burns: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Four Routinely Used Burns Dressings in an Ambulatory Care Setting. J. Burn. Care Res. 2021, 42, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nímia, H.H.; Carvalho, V.F.; Isaac, C.; Souza, F.Á.; Gemperli, R.; Paggiaro, A.O. Comparative Study of Silver Sulfadiazine with Other Materials for Healing and Infection Prevention in Burns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Burns 2019, 45, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Llavero, C.; Morales, V.; Gamallo, C. Total Occlusive Ionic Silver-Containing Dressing vs Mupirocin Ointment Application vs Conventional Dressing in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Effect on Incisional Surgical Site Infection. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015, 221, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, B.R.; Davis, D.M.; Sanchez, J.E.; Mateka, J.J.L.; Nfonsam, V.N.; Frattini, J.C.; Marcet, J.E. The Use of Silver Nylon in Preventing Surgical Site Infections Following Colon and Rectal Surgery. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011, 54, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, C.K.; Hamdan, A.D.; Barshes, N.R.; Wyers, M.; Hevelone, N.D.; Belkin, M.; Nguyen, L.L. Prospective, Randomized, Multi-Institutional Clinical Trial of a Silver Alginate Dressing to Reduce Lower Extremity Vascular Surgery Wound Complications. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 419–427.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuino, G.A.S.; Baluyut-Angeles, K.V.; Espiritu, A.P.T.; Lapitan, M.C.M.; Buckley, B.S. Topical Petrolatum Gel Alone versus Topical Silver Sulfadiazine with Standard Gauze Dressings for the Treatment of Superficial Partial Thickness Burns in Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Burns 2014, 40, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Delivery Form | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Disadvantages | Clinical Applications | Representative Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver Salts | Release Ag+ to directly kill bacteria | Low cost [24]; simple preparation | Low stability; prone to inducing resistance with prolonged use; silver accumulation cytotoxicity risk [25] | Widely used in treatment of burns [26]; combined with antibiotics [27] | Silver sulfadiazine cream [24] |

| Silver-Coupled Electrodes | Electric field-stimulated Ag+ release; interferes with bacterial bioelectrical effects [28] | Strong biofilm penetration [29] | Requires conductive medium; long-term safety requires validation [30] | Chronic wounds; multidrug-resistant infections [31] | Bacterial cellulose-based graphene oxide-silver nanoparticles antibacterial dressing [32] |

| AgNPs | Directly damage bacterial cell membranes [33]; causes oxidative stress [34] | Strong activity; high plasticity [35] | Poor stability; potential systemic toxicity [36] | Implant antibacterial coatings [37] | Porous silver coating [34] |

| Silver-Based polymers | Synergistic action with other materials | Multifunctionality; less resistance [38] | Complex preparation process; biocompatibility of some materials requires validation [39] | Most remain at the laboratory stage | Human Hair Keratin/PEO/PVA Nanofibers [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, Y.; Lu, J.; Guo, X.; Xia, Z.; Ji, S. The Role of Silver and Silver-Based Products in Wound Management: A Review of Advances and Current Landscape. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010027

Du Y, Lu J, Guo X, Xia Z, Ji S. The Role of Silver and Silver-Based Products in Wound Management: A Review of Advances and Current Landscape. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Yiyao, Jianyu Lu, Xinya Guo, Zhaofan Xia, and Shizhao Ji. 2026. "The Role of Silver and Silver-Based Products in Wound Management: A Review of Advances and Current Landscape" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010027

APA StyleDu, Y., Lu, J., Guo, X., Xia, Z., & Ji, S. (2026). The Role of Silver and Silver-Based Products in Wound Management: A Review of Advances and Current Landscape. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010027