Optical Coherence Tomography, Stereomicroscopic, and Histological Aspects of Bone Regeneration on Rat Calvaria in the Presence of Bovine Xenograft or Titanium-Reinforced Hydroxyapatite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Groups

2.3. Biomaterials

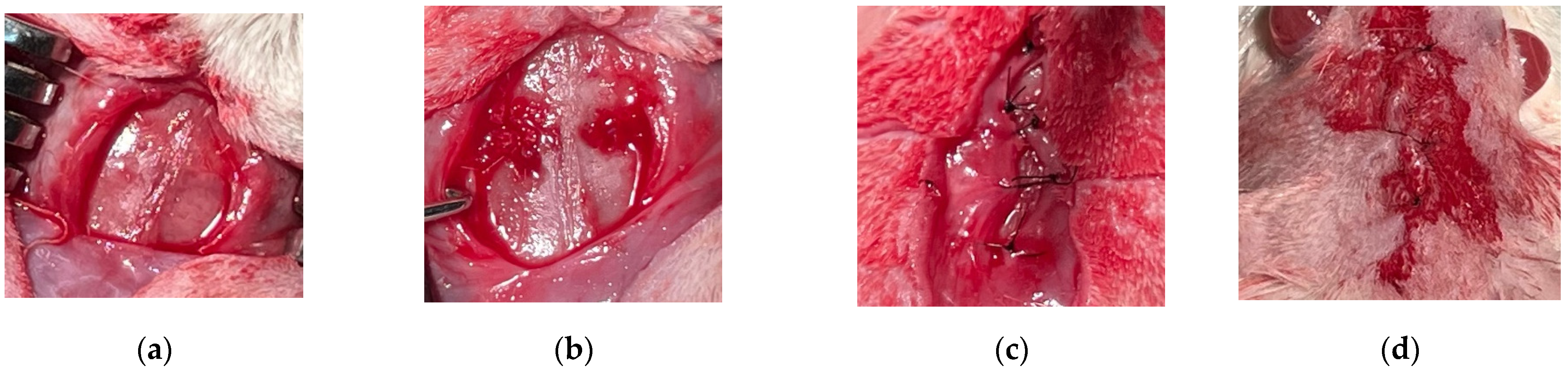

2.4. Surgical Procedure

- -

- Groups A1/A2: negative control group 1/2, in which natural healing was expected, and the animals were sacrificed after 2/4 months.

- -

- Groups B1/B2: positive control group 1/2, in which the bovine xenograft was added, and the animals were sacrificed after 2/4 months.

- -

- Groups C1/C2: study group 1/2, in which the experimental synthetic material based on hydroxyapatite reinforced with titanium particles was grafted, and the animals were sacrificed after 2/4 months.

2.5. Bone Samples Preparation

2.6. OCT Analysis

2.7. Analysis of OCT Images Using Image J Software

2.8. Stereomicroscopic Analysis

2.9. Analysis of Stereomicroscopic Images Using Image J Software

2.10. Histological Analysis

2.11. Analysis of Histologic Images Using Image J Software

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

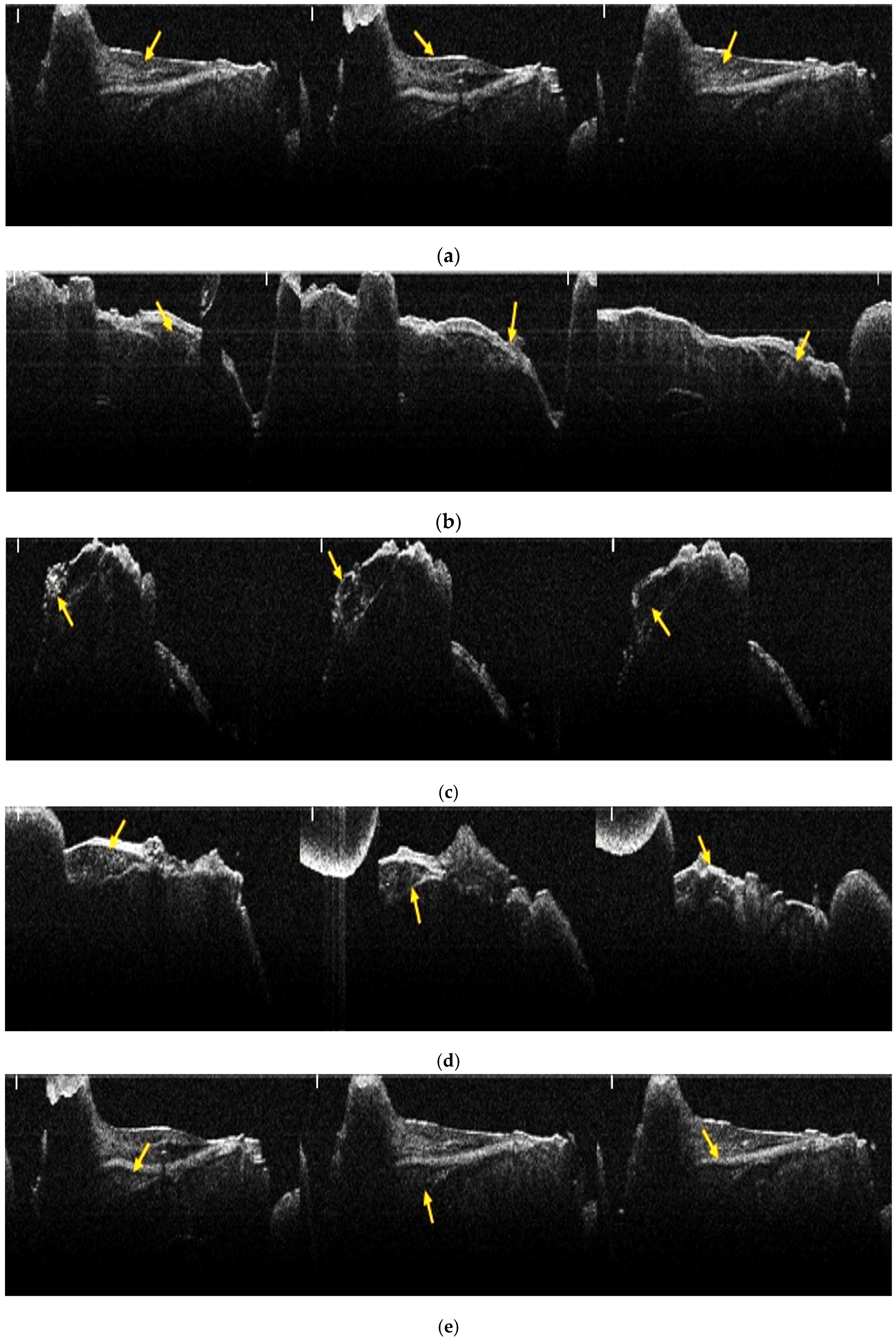

3.1. Results of OCT Analysis of Samples

3.2. Analysis of Bone Evolution Between 2 Months and 4 Months, by Groups and Bone Types

3.3. Groups Comparisons

3.4. Bone Type Analysis

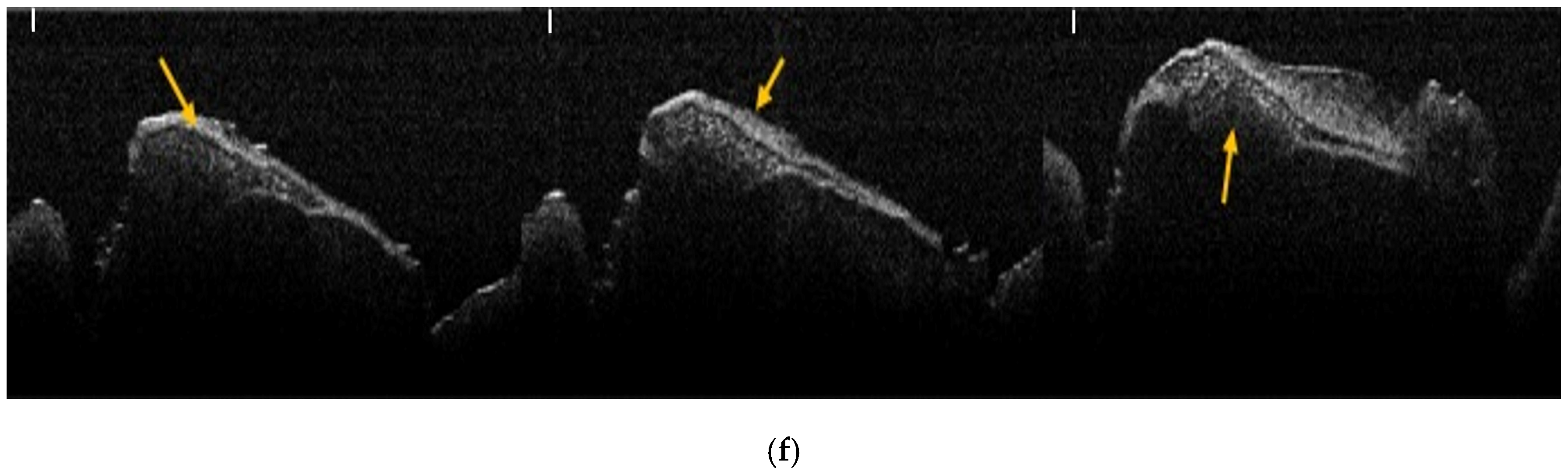

3.5. Results of Stereomicroscopic Analysis of Samples

3.6. Results of Histological Analysis of Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARP | Alveolar ridge preservation |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| TSS | Two- stage sintering |

| IU | International unit |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| HE | Hematoxylin-eosin |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Grossi-Oliveira, G.; Faverani, L.P.; Mendes, B.C.; Braga Polo, T.O.; Batista Mendes, G.C.; de Lima, V.N.; Ribeiro Júnior, P.D.; Okamoto, R.; Magro-Filho, O. Comparative Evaluation of Bone Repair with Four Different Bone Substitutes in Critical Size Defects. Int. J. Biomater. 2020, 2020, 5182845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasilnikova, O.A.; Baranovskii, D.S.; Yakimova, A.O.; Arguchinskaya, N.; Kisel, A.; Sosin, D.; Sulina, Y.; Ivanov, S.A.; Shegay, P.V.; Kaprin, A.D.; et al. Intraoperative Creation of Tissue-Engineered Grafts with Minimally Manipulated Cells: New Concept of Bone Tissue Engineering In Situ. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, G.; Blaauw, D.; Chang, S. A Comparative Study of Two Bone Graft Substitutes-InterOss® Collagen and OCS-B Collagen®. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaddour, A.S.; Ionescu, A.G.; Drăghici, E.C.; Ghiță, R.E.; Mercuț, R.; Manolea, H.O.; Popescu, S.M. Optical coherence tomography qualitative analysis of bone regeneration in rats with titanium reinforced hydroxyapatite biomaterial and porcine bone-derived grafting material. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 17, 905–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Llano, C.H.; López-Tenorio, D.; Saavedra, M.; Zapata, P.A.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. Comparison of Two Bovine Commercial Xenografts in the Regeneration of Critical Cranial Defects. Molecules 2022, 27, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Fang, J.J.; Lee, J.N.; Periasamy, S.; Yen, K.C.; Wang, H.C.; Hsieh, D.J. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Decellularized Xenograft-3D CAD/CAM Carved Bone Matrix Personalized for Human Bone Defect Repair. Genes 2022, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikael, P.E.; Golebiowska, A.A.; Xin, X.; Rowe, D.W.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Evaluation of an Engineered Hybrid Matrix for Bone Regeneration via Endochondral Ossification. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigério, P.B.; Quirino, L.C.; Gabrielli, M.A.C.; Carvalho, P.H.A.; Garcia Júnior, I.R.; Pereira-Filho, V.A. Evaluation of Bone Repair Using a New Biphasic Synthetic Bioceramic (Plenum® Osshp) in Critical Calvaria Defect in Rats. Biology 2023, 12, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsi, A.S.; Kalsi, J.S.; Bassi, S. Alveolar ridge preservation: Why, when and how. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasami, H.; Dey, M.K.; Devireddy, R. Three-Dimensional Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, M.; Čandrlić, M.; Juzbašić, M.; Ivanišević, Z.; Matijević, N.; Včev, A.; Cvijanović Peloza, O.; Matijević, M.; Perić Kačarević, Ž. Synthetic Injectable Biomaterials for Alveolar Bone Regeneration in Animal and Human Studies. Materials 2021, 14, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, R.; Kovács, A.; Berkó, S.; Budai-Szűcs, M. Developments in Alloplastic Bone Grafts and Barrier Membrane Biomaterials for Periodontal Guided Tissue and Bone Regeneration Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, C.W.; Al-Namnam, N.M.; Lau, M.N.; Lim, G.S.; Raman, R.; Fairbairn, P.; Ngeow, W.C. Synthetic Material for Bone, Periodontal, and Dental Tissue Regeneration: Where Are We Now, and Where Are We Heading Next? Materials 2021, 14, 6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuba, S.; Okada, M.; Nohara, K.; Iwata, T. Alloplastic Bone Substitutes for Periodontal and Bone Regeneration in Dentistry: Current Status and Prospects. Materials 2021, 14, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Płociński, P.; Kupikowska-Stobba, B.; Urbaniak, M.M.; Rusek-Wala, P.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Piszko, P.; Krupa, A.; Biernat, M.; Gazińska, M.; et al. Bioactive Materials for Bone Regeneration: Biomolecules and Delivery Systems. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 5222–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Clark-Perry, D. Use of a Novel In Situ Hardening Biphasic Alloplastic Bone Grafting Material for Guided Bone Regeneration Around Dental Implants: A Prospective Case Series. Clin. Adv. Periodontics 2022, 12, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, A.; Duncan, W.; Li, K.C.; Waddell, J.N.; Coates, D. Comparison of Low and High Temperature Sintering for Processing of Bovine Bone as Block Grafts for Oral Use: A Biological and Mechanical In Vitro Study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, P.; Li, D.J.; Auston, D.A.; Mir, H.S.; Yoon, R.S.; Koval, K.J. Autograft, Allograft, and Bone Graft Substitutes: Clinical Evidence and Indications for Use in the Setting of Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery. J. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 33, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Qi, Y.; Ma, X.; Qiao, S.; Cai, H.; Zhao, B.C.; Jiang, H.B.; Lee, E.S. Comparison of Autogenous Tooth Materials and Other Bone Grafts. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Labrador, L.; Molinero-Mourelle, P.; Pérez-González, F.; Saez-Alcaide, L.M.; Brinkmann, J.C.; Martínez, J.L.; Martínez-González, J.M. Clinical performance of alveolar ridge augmentation with xenogeneic bone block grafts versus autogenous bone block grafts. A systematic review. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 122, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Shimabukuro, M.; Kishida, R.; Tsuchiya, A.; Ishikawa, K. Structurally optimized honeycomb scaffolds with outstanding ability for vertical bone augmentation. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 41, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashtasbi, F.; Hasannia, S.; Hasannia, S.; Mahdi Dehghan, M.; Sarkarat, F.; Shali, A. Comparative study of impact of animal source on physical, structural, and biological properties of bone xenograft. Xenotransplantation 2020, 27, e12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picciolo, G.; Peditto, M.; Irrera, N.; Pallio, G.; Altavilla, D.; Vaccaro, M.; Picciolo, G.; Scarfone, A.; Squadrito, F.; Oteri, G. Preclinical and Clinical Applications of Biomaterials in the Enhancement of Wound Healing in Oral Surgery: An Overview of the Available Reviews. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, V.G.; Dall Agnol, G.S.; Campista, C.C.C.; Bury, L.L.; Ervolino, E.; Longo, M.; Mulinari-Santos, G.; Levin, L.; Theodoro, L.H. Evaluation of Two Anorganic Bovine Xenogenous Grafts in Bone Healing of Critical Defect in Rats Calvaria. Braz. Dent. J. 2024, 35, e246119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Dahlin, C.; Apatzidou, D.; Artzi, Z.; Bozic, D.; Calciolari, E.; Schliephake, H. Biomaterials and regenerative technologies used in bone regeneration in the craniomaxillofacial region: Consensus report of group 2 of the 15th European Workshop on Periodontology on Bone Regeneration. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naini, A.Y.; Kobravi, S.; Jafari, A.; Lotfalizadeh, M.; Lotfalizadeh, N.; Farhadi, S. Comparing the effects of Bone+B® xenograft and InterOss® xenograft bone material on rabbit calvaria bone defect regeneration. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J.A. Risks of Infectious Disease in Xenotransplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2258–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falacho, R.I.; Palma, P.J.; Marques, J.A.; Figueiredo, M.H.; Caramelo, F.; Dias, I.; Viegas, C.; Guerra, F. Collagenated Porcine Heterologous Bone Grafts: Histomorphometric Evaluation of Bone Formation Using Different Physical Forms in a Rabbit Cancellous Bone Model. Molecules 2021, 26, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, R.; Demer, A.; Ochoa, S.; Arpey, C. Bovine Collagen Xenografts as Cost-Effective Adjuncts for Granulating Surgical Defects. Dermatol. Surg. 2024, 50, 884–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfazar, M.; Amid, R.; Moscowchi, A. Potentials of pure xenograft materials in maxillary ridge augmentation: A case series. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi-Ghalehlou, N.; Feizkhah, A.; Mobayen, M.; Pourmohammadi-Bejarpasi, Z.; Shekarchi, S.; Roushandeh, A.M.; Roudkenar, M.H. Plumping up a Cushion of Human Biowaste in Regenerative Medicine: Novel Insights into a State-of-the-Art Reserve Arsenal. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 2709–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susin, C.; Lee, J.; Fiorini, T.; Koo, K.T.; Schüpbach, P.; Finger Stadler, A.; Wikesjö, U.M. Screening of Hydroxyapatite Biomaterials for Alveolar Augmentation Using a Rat Calvaria Critical-Size Defect Model: Bone Formation/Maturation and Biomaterials Resolution. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, R.J. Optimized bone grafting. Periodontology 2000 2024, 94, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obadan, F.; Craitoiu, M.; Manolea, H.; Mogoanta, L.; Osiac, E.; Rica, R.; Earar, K. Osseointegration Evaluation of Two Socket Preservation Materials in Small Diameter Bone Cavities An in vivo lab rats study. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 2904–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiblein, M.; Winkenbach, A.; Koch, E.; Schaible, A.; Büchner, H.; Marzi, I.; Nau, C. Impact of scaffold granule size use in Masquelet technique on periosteal reaction: A study in rat femur critical size bone defect model. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Born, G.; Chaaban, M.; Scherberich, A. Natural Polymeric Scaffolds in Bone Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Junior, J.M.; Montagner, P.G.; Carrijo, R.C.; Martinez, E.F. Physical characterization of biphasic bioceramic materials with different granulation sizes and their influence on bone repair and inflammation in rat calvaria. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matichescu, A.; Ardelean, L.C.; Rusu, L.C.; Craciun, D.; Bratu, E.A.; Babucea, M.; Leretter, M. Advanced Biomaterials and Techniques for Oral Tissue Engineering and Regeneration-A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudecki, A.; Łyko-Morawska, D.; Kasprzycka, A.; Kazek-Kęsik, A.; Likus, W.; Hybiak, J.; Jankowska, K.; Kolano-Burian, A.; Włodarczyk, P.; Wolany, W.; et al. Comparison of Physicochemical, Mechanical, and (Micro-)Biological Properties of Sintered Scaffolds Based on Natural- and Synthetic Hydroxyapatite Supplemented with Selected Dopants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, C.; Gayathri, V.S.; Sowmya, S.V.; Augustine, D.; Alamoudi, A.; Zidane, B.; Hassan Mohammad Albar, N.; Bhandi, S. Nanohydroxyapatite in dentistry: A comprehensive review. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuri, A.S.; Shehada, A.; Darwich, K.; Saima, R. Radiological Comparative Study Between Conventional and Nano Hydroxyapatite With Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) Membranes for Their Effects on Alveolar Bone Density. Cureus 2022, 14, e32381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohner, M.; Santoni, B.L.G.; Döbelin, N. β-tricalcium phosphate for bone substitution: Synthesis and properties. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaddour, A.S.; Drăghici, E.C.; Ionescu, M.; Andrei, C.E.; Ghiţă, R.E.; Mercuţ, R.; Gîngu, O.; Sima, G.; Toma Tumbar, L.; Popescu, S.M. Bone Regeneration in Defects Created on Rat Calvaria Grafted with Porcine Xenograft and Synthetic Hydroxyapatite Reinforced with Titanium Particles-A Microscopic and Histological Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, L.F.; Nayak, V.V.; Benalcázar Jalkh, E.B.; Tovar, N.; Chiu, K.J.; Salas, J.C.; Marin, C.; Bowers, M.; Freitas, G.; Mbe Fokam, D.C.; et al. Laddec® versus Bio-Oss®: The effect on the healing of critical-sized defect–Calvaria rabbit model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 2744–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, F.E.; McNamara, L.M. Endochondral Priming: A Developmental Engineering Strategy for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2017, 23, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Jia, L.; Duan, K.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yan, J.; Duan, X.; Wu, G. Preparation and properties of a new artificial bone composite material. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2023, 37, 488–494. [Google Scholar]

- Ardelean, A.I.; Mârza, S.M.; Marica, R.; Dragomir, M.F.; Rusu-Moldovan, A.O.; Moldovan, M.; Pașca, P.M.; Oanam, L. Evaluation of Biocomposite Cements for Bone Defect Repair in Rat Models. Life 2024, 14, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, B.; Apaza Alccayhuaman, K.A.; Strauss, F.J.; Lee, J.S.; Tangl, S.; Kuchler, U.; Gruber, R. Osteoconductive properties of upside-down bilayer collagen membranes in rat calvarial defects. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khijmatgar, S.; Panda, S.; Biagi, R.; Rovati, M.; Colletti, L.; Goker, F.; Greco Lucchina, A.; Mortellaro, C.; Del Fabbro, M. Optical coherence tomography application for assessing variation in bone mineral content: A preclinical study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Leitgeb, R.; Placzek, F.; Rank, E.; Krainz, L.; Haindl, R.; Li, Q.; Liu, M.; Andreana, M.; Unterhuber, A.; Schmoll, T.; et al. Enhanced medical diagnosis for dOCTors: A perspective of optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 2021, 26, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Gilani, S.B.S.; Shabbir, J.; Almulhim, K.S.; Bugshan, A.; Farooq, I. Optical coherence tomography’s current clinical medical and dental applications: A review. F1000Res 2021, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăghici, M.A.; Mitruţ, I.; Sălan, A.I.; Mărăşescu, P.C.; Caracaş, R.E.; Camen, A.; Manolea, H.O. Osseointegration evaluation of an experimental bone graft material based on hydroxyapatite, reinforced with titanium-based particles. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2023, 64, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho Reis, E.N.R.; Bezerra Júnior, G.L.; de Freitas Silva, L.; Braga Polo, T.O.; de Amorim, R.A.; Ponzoni, D.; Okamoto, R.; de Molon, R.S.; Faverani, L.P.; Garcia Junior, I.R. Evaluation of bone regeneration in rat calvaria using combination of enamel matrix derivate and bone graft substitute: A histological, histometric and immunohistochemical study. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 29, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zheng, H.; Guo, Y.; Heng, B.C.; Yang, Y.; Yao, W.; Jiang, S. A three-dimensional actively spreading bone repair material based on cell spheroids can facilitate the preservation of tooth extraction sockets. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1161192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.W.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, S.Y. Effect of hydroxyapatite on critical-sized defect. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 38, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanbhag, S.; Suliman, S.; Mohamed-Ahmed, S.; Kampleitner, C.; Hassan, M.N.; Heimel, P.; Dobsak, T.; Tangl, S.; Bolstad, A.I.; Mustafa, K. Bone regeneration in rat calvarial defects using dissociated or spheroid mesenchymal stromal cells in scaffold-hydrogel constructs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Saini, M.; Dehiya, B.S.; Sindhu, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Lamberti, L.; Pruncu, C.I.; Thakur, R. Comprehensive Survey on Nanobiomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, A.; Jolette, J. Bone Toolbox: Biomarkers, Imaging Tools, Biomechanics, and Histomorphometry. Toxicol. Pathol. 2018, 46, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, V.M.; Agnew, A.M. The use of ROI overlays and a semi-automated method for measuring cortical area in ImageJ for histological analysis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2019, 168, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, C.; Sofronia, A.; Anghel, E.M.; Baies, R.; Constantin, D.; Seciu, A.M.; Tanasescu, S. Microstructure, stability and biocompatibility of hydroxyapatite–titania nanocomposites formed by two step sintering process. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingu, O.; Benga, G.; Olei, A.; Lupu, N.; Rotaru, P.; Tanasescu, S.; Sima, G. Wear behaviour of ceramic biocomposites based on hydroxiapatite nanopowders. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2011, 225, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, R.E.; Todea, C.D.; Duma, V.F.; Bradu, A.; Podoleanu, A.G. Quantitative assessment of rat bone regeneration using complex master-slave optical coherence tomography. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caracaş, R.E.; Osiac, E.; Ciocan, L.T.; Mihăiescu, D.E.; Buteică, S.A.; Mitruţ, I.; Manolea, H.O. An optical coherence tomography evaluation of two synthetic bone augmentation materials in calvaria and mandibular lab rats cavities. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 13, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Pin, K.; Aziz, A.; Han, J.W.; Nam, Y. Optical Coherence Tomography Image Classification Using Hybrid Deep Learning and Ant Colony Optimization. Sensors 2023, 23, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-del-Pliego, E.; Vilaplana, L.; Güerri-Fernández, R.; Diez-Pérez, A. Measuring bone quality. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2013, 15, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghban, A.A.; Dehghani, A.; Ghanavati, F.; Zayeri, F.; Ghanavati, F. Comparing alveolar bone regeneration using Bio-Oss and autogenous bone grafts in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. Endod. J. 2009, 4, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Rădoi, M.A.; Osiac, E.; Lascu, L.C.; Gîngu, O.; Mitruț, I.; Sălan, A.I.; Manolea, H.O. A digital approach for the analysis of the optical coherence tomography evaluation of hydroxyapatite–based bone graft materials. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 15, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kasseck, C.; Kratz, M.; Torcasio, A.; Gerhardt, N.C.; van Lenthe, G.H.; Gambichler, T.; Hoffmann, K.; Jones, D.B.; Hofmann, M.R. Comparison of optical coherence tomography, microcomputed tomography, and histology at a three-dimensionally imaged trabecular bone sample. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010, 15, 046019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.B.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, J.J.; Bae, H.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Huh, J.B. Comparison of Bone Regeneration between Porcine-Derived and Bovine-Derived Xenografts in Rat Calvarial Defects: A Non-Inferiority Study. Materials 2019, 12, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielenstein, J.; Radenković, M.; Najman, S.; Liu, L.; Ren, Y.; Cai, B.; Beuer, F.; Rimashevskiy, D.; Schnettler, R.; Alkildani, S.; et al. In Vivo Analysis of the Regeneration Capacity and Immune Response to Xenogeneic and Synthetic Bone Substitute Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Integrated Density | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Months | 4 Months | Differences (2 Months–4 Months) | |||||||||

| Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p */ Cohen’s d | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | ||

| Negative control group | Native bone | 13.36 | 23.52 | 19.878 ± 4.297 | 9.22 | 20.58 | 16.012 ± 4.091 | 3.866 ± 3.769 | 0.141/ 0.992 | −1.530 | 9.262 |

| Defect area | 28.87 | 41.24 | 33.539 ± 4.61 | 17.23 | 40.03 | 32.849 ± 8.63 | 0.691 ± 9.266 | 0.866/ 0.100 | −8.209 | 9.590 | |

| Newly formed bone | 8.62 | 20.78 | 15.369 ± 4.818 | 12.43 | 24.86 | 19.689 ± 4.885 | −4.32 ± 7.633 | 0.154/ 0.890 | −10.560 | 1.920 | |

| Positive control group | Native bone | 15.95 | 35.05 | 25.48 ± 8.172 | 13.49 | 22.03 | 16.493 ± 3.064 | 8.987 ± 7.534 | 0.043 #/ 1.456 | 0.392 | 17.580 |

| Defect area | 46.18 | 78.72 | 59.382 ± 12.322 | 27.97 | 71.91 | 52.33 ± 15.979 | 7.053 ± 12.988 | 0.412/ 0.494 | −11.301 | 25.407 | |

| Newly formed bone | 21.82 | 28.75 | 25.183 ± 3.065 | 14.9 | 27.69 | 18.583 ± 5.299 | 6.6 ± 7.791 | 0.025 #/ 1.525 | 1.031 | 12.168 | |

| Study group | Native bone | 12.66 | 23.6 | 17.66 ± 3.643 | 11.55 | 15.92 | 13.979 ± 1.645 | 3.681 ± 4.803 | 0.048 #/ 1.302 | 0.045 | 7.317 |

| Defect area | 50.2 | 85.87 | 65.442 ± 14.967 | 52.56 | 90.21 | 74.583 ± 12.792 | −9.141 ± 19.433 | 0.282/ 0.657 | −27.050 | 8.769 | |

| Newly formed bone | 11.58 | 25.07 | 19.698 ± 4.622 | 15.59 | 32.86 | 21.852 ± 5.786 | −2.154 ± 7.497 | 0.493/ 0.411 | −8.890 | 4.582 | |

| Group | Bone Type | 2 Months | 4 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control group | ANOVA/p/ω2 | (F(2, 15)) 25.608/<0.0005 #, ω2 = 0.732 | (F(2, 15)) 12.258/0.001 #, ω2 = 0.556 | ||

| Multiple group comparisons | Variation | p ** | Variation | p * | |

| Native—Defect area | −13.661 | <0.0005 | −16.837 | 0.001 | |

| Defect area—Newly formed | 18.170 | <0.0005 | 13.159 | 0.006 | |

| Native—Newly formed | 4.509 | 0.236 | −3.677 | 0.571 | |

| Positive control group | ANOVA/p/ω2 | (F(2, 15)) 30.515/<0.0005 #, ω2 = 0.766 | (F(2, 8.375)) 13.531/0.002 ##, ω2 = 0.726 | ||

| Multiple group comparisons | Variation | p * | Variation | p ** | |

| Native—Defect area | −33.902 | <0.0005 | −35.836 | 0.006 | |

| Defect area—Newly formed | 34.199 | <0.0005 | 33.746 | 0.006 | |

| Native—Newly formed | 0.297 | 0.998 | −2.089 | 0.693 | |

| Study group | ANOVA/p/ω2 | (F(2, 8.936)) 26.894/<0.0005 ##, ω2 = 0.462 | (F(2, 15)) 97.811/<0.0005 #, ω2 = 0.915 | ||

| Multiple group comparisons | Variation | p ** | Variation | p ** | |

| Native—Defect area | −47.782 | 0.001 | −60.604 | <0.0005 | |

| Defect area—Newly formed | 45.743 | 0.001 | 52.730 | <0.0005 | |

| Native—Newly formed | −2.038 | 0.684 | −7.873 | 0.248 | |

| Bone Type | Group | 2 Months | 4 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native bone | ANOVA/p/ω2 | (F(2, 9.368)) 2.220/0.162 ##, ω2 = 0.179 | (F(2, 15)) 1.112/0.355 #, ω2 = 0.012 | ||

| Multiple group comparisons | Variation | p ** | Variation | p * | |

| Negative control—Positive control | - | - | - | - | |

| Positive control—Study | - | - | - | - | |

| Negative control—Study | - | - | - | - | |

| Defect area | ANOVA/p/ω2 | (F(2, 15)) 13.013/0.001 #, ω2 = 0.572 | (F(2, 15)) 15.907/<0.0005 #, ω2 = 0.624 | ||

| Multiple group comparisons | Variation | p * | Variation | p * | |

| Negative control—Positive control | −25.843 | 0.004 | −19.481 | 0.047 | |

| Positive control—Study | −6.059 | 0.641 | −22.253 | 0.023 | |

| Negative control—Study | −31.902 | 0.001 | −41.734 | < 0.0005 | |

| Newly formed bone | ANOVA/p/ω2 | (F(2, 15)) 8.068/0.004 #, ω2 = 0.440 | (F(2, 15)) 0.583/0.571 #, ω2 = 0.049 | ||

| Multiple group comparisons | Variation | p * | Variation | p * | |

| Negative control—Positive control | −9.814 | 0.003 | - | - | |

| Positive control—Study | 5.485 | 0.097 | - | - | |

| Negative control—Study | −4.329 | 0.214 | - | - | |

| Sample | Measurements | p (2M-4M)/Cohen’s d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Months | 4 Months | ||||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | ||

| Positive Control Group (Bovine Xenograft) | 0.502 | 0.156 | 0.313 | 0.059 | 0.042 *,#/1.316 |

| Study Group (Synthetic Hydroxyapatite reinforced with Titanium particles) | 0.403 | 0.092 | 0.396 | 0.083 | 0.894 */ 0.186 |

| p/Cohen’s d | 0.306 **/0.523 | 0.066 **/1.159 | |||

| Sample | Bone Surface | Mean Thickness of the Trabeculae | Mean Diameter of the Osteocytes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Months | 4 Months | p */d | 2 Months | 4 Months | p * | 2 Months | 4 Months | p */d | ||

| Negative Control | Mean ± SD | 85.972 ± 120.942 | 60.25 ± 94.353 | 0.717/0.237 | 7.270 ± 25.371 | 6.209 ± 24.435 | 0.030 #/0.043 | 14.53 ± 40.607 | 13.965 ± 41.768 | 0.679/0.014 |

| Median | 35.970 | 7.650 | 2.734 | 2.734 | 8.816 | 8.201 | ||||

| Positive Control | Mean ± SD | 75.467 ± 105.102 | 82.387 ± 112.114 | 0.922/0.064 | 13.788 ± 46.655 | 11.751 ± 49.391 | 0.349/0.042 | 20.196 ± 58.600 | 16.034 ± 62.617 | 0.242/0.069 |

| Median | 35.970 | 40.230 | 5.114 | 6.234 | 7.128 | 7.828 | ||||

| Study Group | Mean ± SD | 43.887 ± 70.225 | 35.752 ± 57.168 | 0.846/0.127 | 12.939 ± 32.158 | 10.349 ± 23.597 | 0.010 #/0.092 | 18.116 ± 39.244 | 11.589 ± 29.054 | <0.0005 #/0.189 |

| Median | 6.123 | 5.210 | 6.583 | 7.732 | 8.201 | 7.828 | ||||

| p **/η2 | 0.614/ 0.002 | 0.331/0.093 | <0.0005 #/0.053 | <0.0005 #/0.131 | 0.001 #/0.004 | 0.560/0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Radu, A.; Khaddour, A.S.; Ionescu, M.; Munteanu, C.M.; Osiac, E.; Gîngu, O.; Teișanu, C.; Mateescu, V.O.; Andrei, C.E.; Popescu, S.M. Optical Coherence Tomography, Stereomicroscopic, and Histological Aspects of Bone Regeneration on Rat Calvaria in the Presence of Bovine Xenograft or Titanium-Reinforced Hydroxyapatite. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010026

Radu A, Khaddour AS, Ionescu M, Munteanu CM, Osiac E, Gîngu O, Teișanu C, Mateescu VO, Andrei CE, Popescu SM. Optical Coherence Tomography, Stereomicroscopic, and Histological Aspects of Bone Regeneration on Rat Calvaria in the Presence of Bovine Xenograft or Titanium-Reinforced Hydroxyapatite. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadu, Andrei, Antonia Samia Khaddour, Mihaela Ionescu, Cristina Maria Munteanu, Eugen Osiac, Oana Gîngu, Cristina Teișanu, Valentin Octavian Mateescu, Cristina Elena Andrei, and Sanda Mihaela Popescu. 2026. "Optical Coherence Tomography, Stereomicroscopic, and Histological Aspects of Bone Regeneration on Rat Calvaria in the Presence of Bovine Xenograft or Titanium-Reinforced Hydroxyapatite" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010026

APA StyleRadu, A., Khaddour, A. S., Ionescu, M., Munteanu, C. M., Osiac, E., Gîngu, O., Teișanu, C., Mateescu, V. O., Andrei, C. E., & Popescu, S. M. (2026). Optical Coherence Tomography, Stereomicroscopic, and Histological Aspects of Bone Regeneration on Rat Calvaria in the Presence of Bovine Xenograft or Titanium-Reinforced Hydroxyapatite. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010026