Sustainable Valorization of Mussel Shell Waste: Processing for Calcium Carbonate Recovery and Hydroxyapatite Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Calcium Carbonate from Mussel Shells

2.1.1. Collection and Pre-Treatment

2.1.2. Grinding and Milling

2.2. Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite (HA)

Wet Chemical Synthesis

2.3. Morphological Characterization of CaCO3 Powder and Synthesized HA

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization of Synthesized Materials

2.4.1. Physicochemical Characterization of CaCO3 Powder and Synthesized HA

2.4.2. Thermal Analysis

2.4.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4.4. Raman Spectroscopic Analysis

2.4.5. X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopic Analysis (XRF)

2.4.6. Nanoscale Morphology and Density Characterization

2.5. Biological Evaluation of CaCO3 Powder and Synthesized HA for Biomedical Applications

2.5.1. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

2.5.2. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.5.3. Odontogenic Differentiation Assays

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characterization of CaCO3 Powder and Synthesized HA

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Synthesized Materials

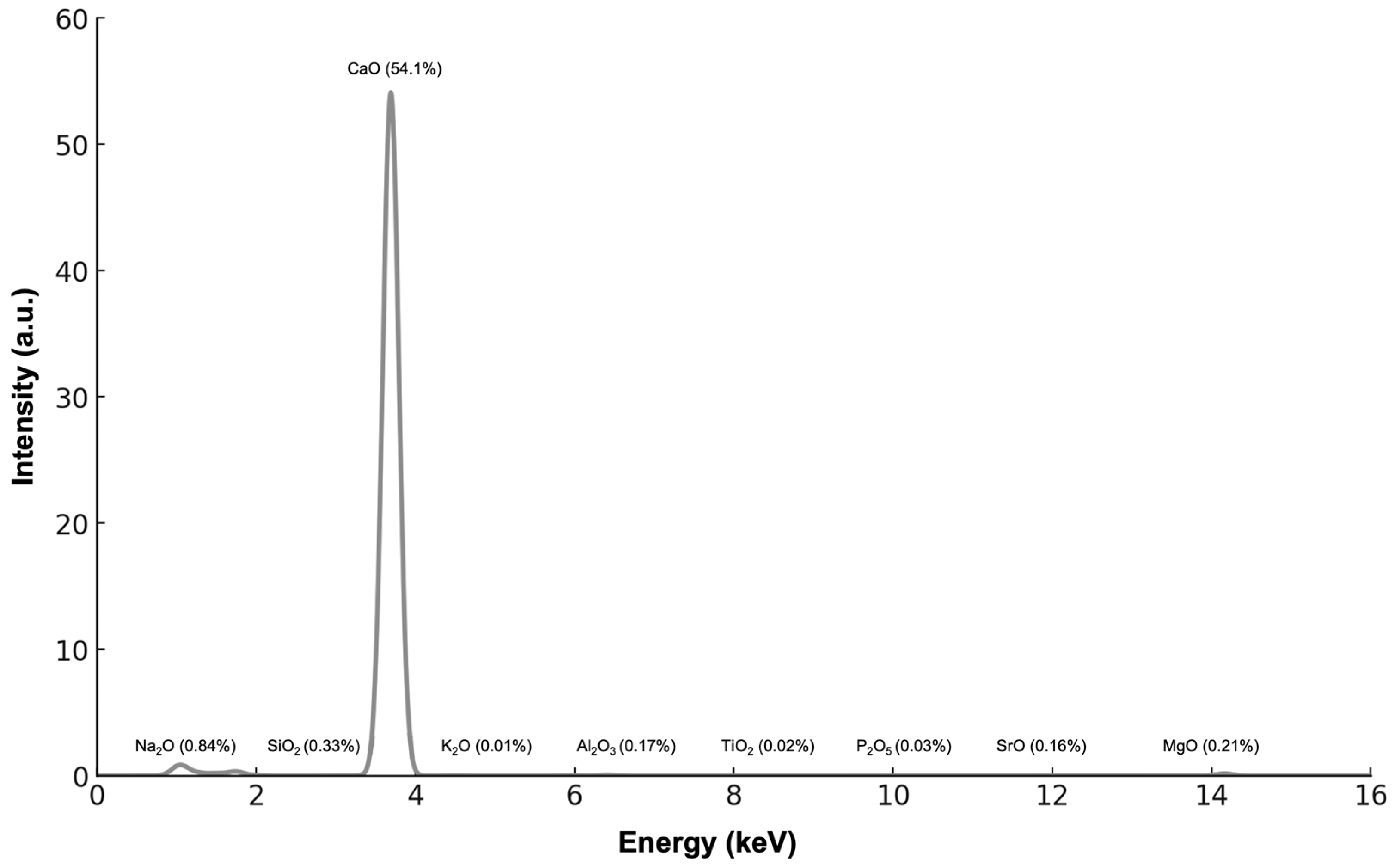

3.2.1. X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopic Analysis (XRF)

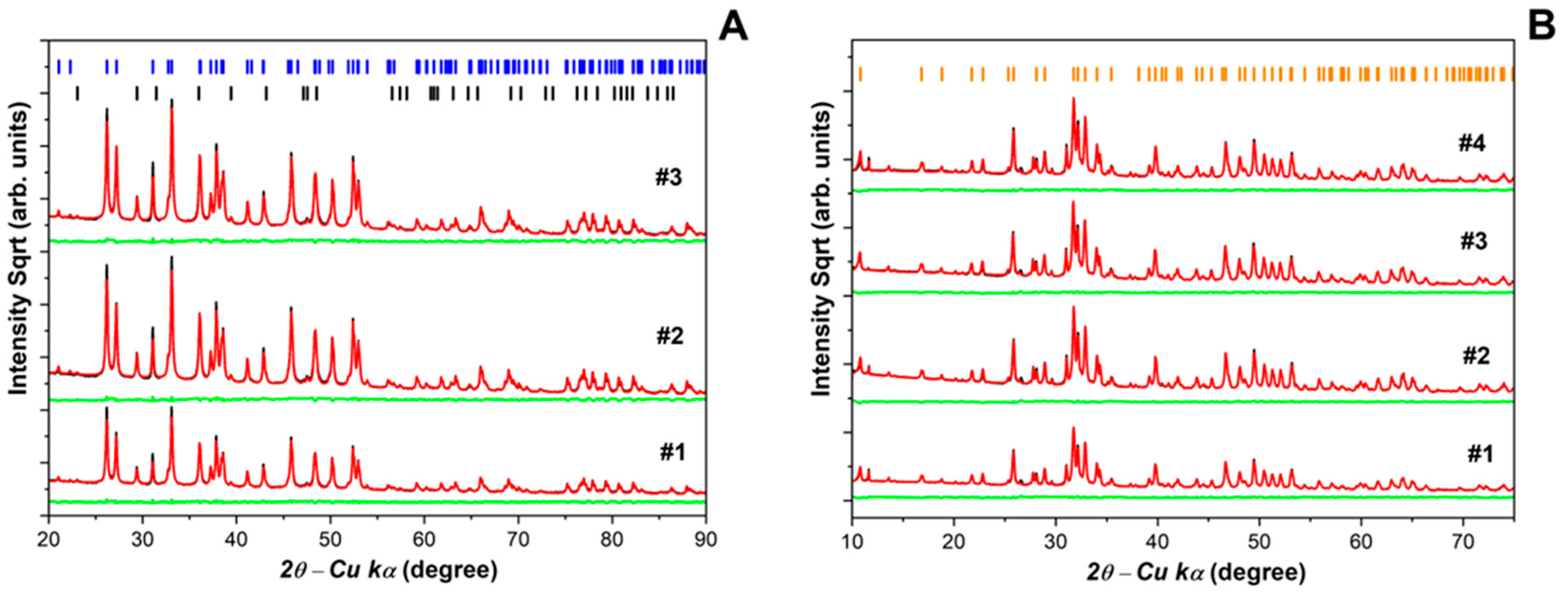

3.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

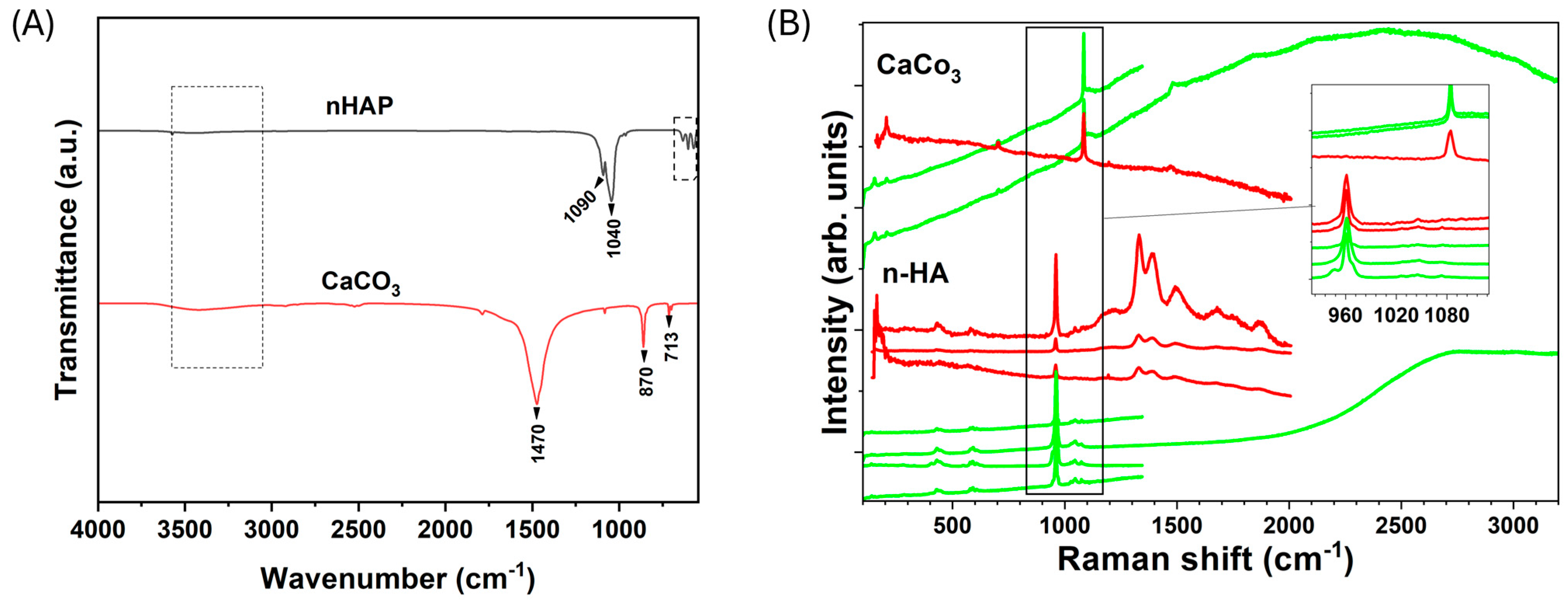

3.2.3. Raman and FTIR Spectroscopic Analyses

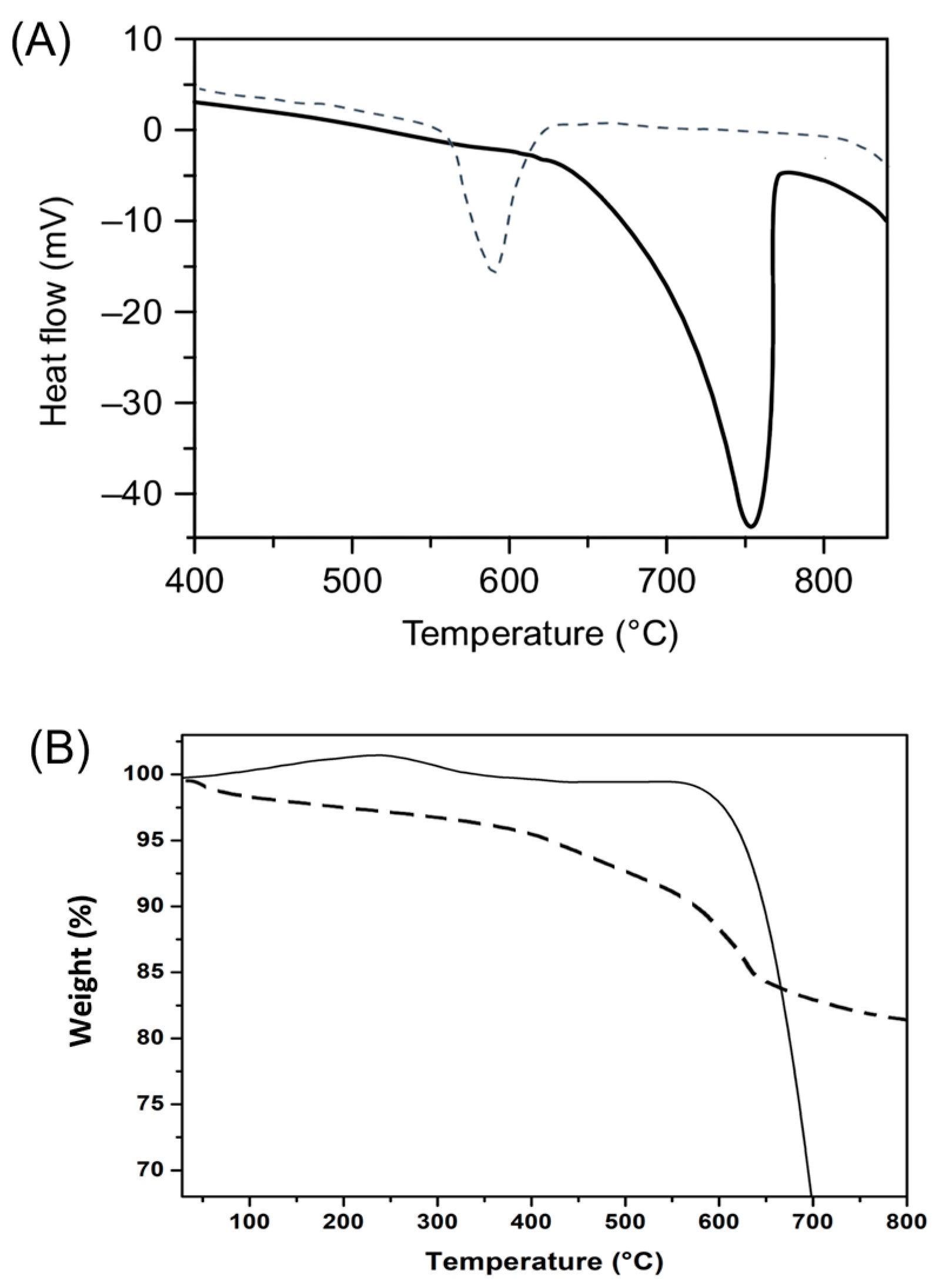

3.2.4. Thermal Analysis

3.2.5. Nanoscale Refinement and Characterization

3.3. Biological Evaluation of CaCO3 and HA Particles for Biomedical Applications

3.3.1. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

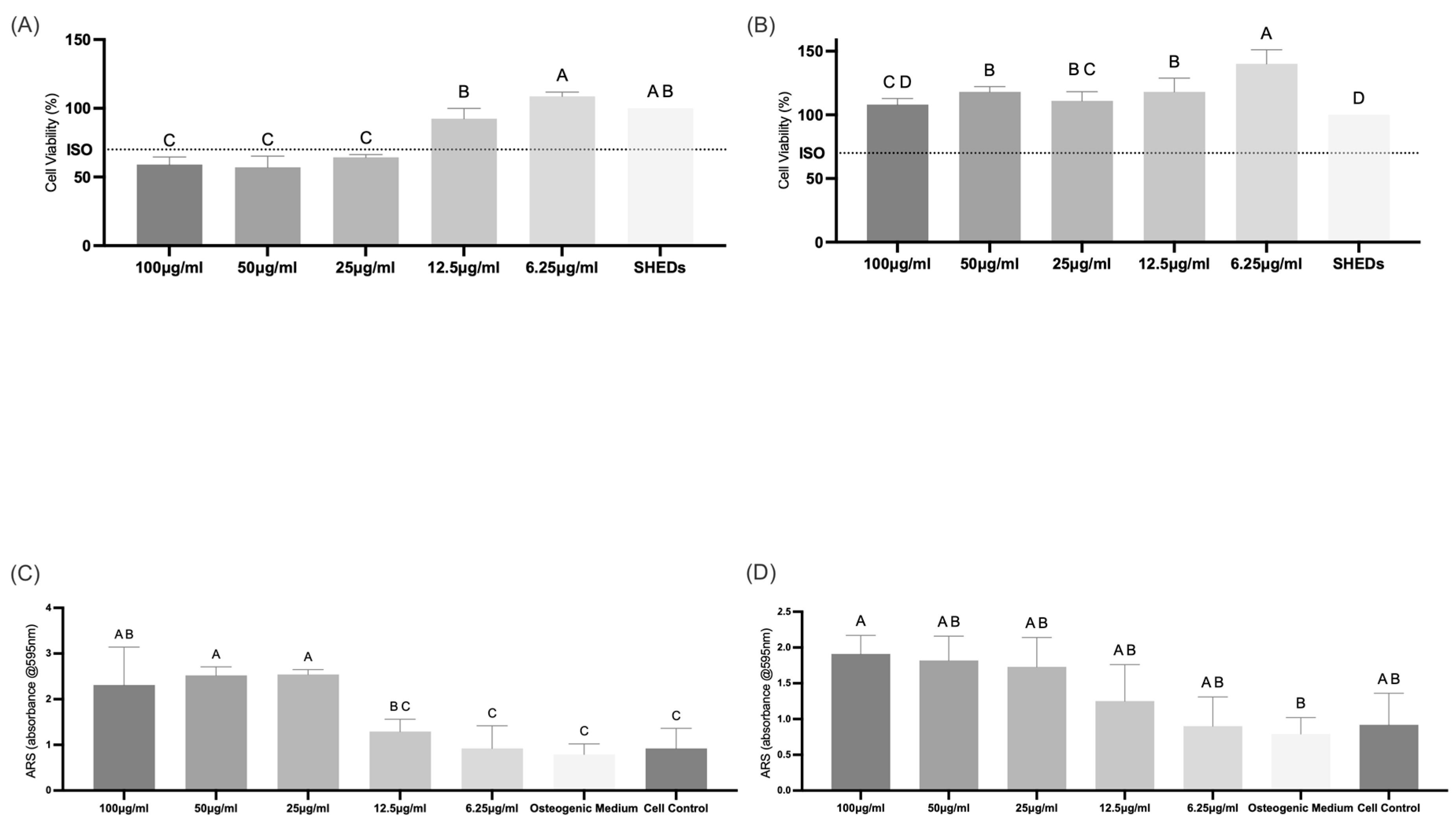

3.3.2. Cell Viability

3.3.3. Extracellular Mineralization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shariffuddin, J.H.; Jones, M.I.; Patterson, D.A. Greener photocatalysts: Hydroxyapatite derived from waste mussel shells for the photocatalytic degradation of a model azo dye wastewater. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2013, 91, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavandi, A.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A.; Ali, A.; Sun, Z. Synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite (HA) from waste mussel shells using a rapid microwave method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 149, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.S.; Girija, E.K.; Venkatesh, M.; Karunakaran, G.; Kolesnikov, E.; Kuznetsov, D. One step method to synthesize flower-like hydroxyapatite architecture using mussel shell bio-waste as a calcium source. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 3457–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Nguyen, T.P.; Pham, V.H.; Hoang, G.; Manivasagan, P. Marine shell-derived calcium phosphate for biomedical applications: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 120, 111695. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K. Shellfish waste-derived calcium oxide and its applications. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Flórez, V.; Santos, A.; Lemus-Ruiz, J. From waste to biomaterials: The use of shellfish shells for bone regeneration. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114085. [Google Scholar]

- Piras, S.; Salathia, S.; Guzzini, A.; Zovi, A.; Jackson, S.; Smirnov, A.; Fragassa, C.; Santulli, C. Biomimetic Use of Food-Waste Sources of Calcium Carbonate and Phosphate for Sustainable Materials—A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Shil, S.K.; Pallab, M.S.; Islam, K.N.; Sutradhar, B.C.; Das, B.C. Experimental long bone fracture healing in goats with cockle shell-based calcium carbonate bone paste. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2024, 25, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Águila-Almanza, E.; Hernández-Cocoletzi, H.; Rubio-Rosas, E.; Calleja-González, M.; Lim, H.R.; Khoo, K.S.; Singh, V.; Maldonado-Montiel, J.C.; Show, P.L. Recuperation and characterization of calcium carbonate from residual oyster and clamshells and their incorporation into a residential finish. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.H.E.; Checa, A.G.; Gale, J.D.; Gebauer, D.; Sainz-Díaz, C.I. Calcium carbonate polyamorphism and its role in biomineralization: How many amorphous calcium carbonates are there? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11960–11970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, C.; Degnan, B.M. The evolution of mollusc shells. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2018, 7, e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, R.J.M.; ten Cate, J.M. The anti-caries efficacy of calcium carbonate-based fluoride toothpastes. Int. Dent. J. 2005, 55, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandiffio, P.; Mantilla, T.; Amaral, F.; França, F.; Basting, R.; Turssi, C. Anti-erosive effect of calcium carbonate suspensions. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e776–e780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.-Q.; Liu, J.-H.; Aymonier, C.; Fermani, S.; Kralj, D.; Falini, G.; Zhou, C.H. Calcium carbonate: Controlled synthesis, surface functionalization, and nanostructured materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 7883–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lin, J.; Fu, L.-H.; Huang, P. Calcium-based biomaterials for diagnosis, treatment, and theranostics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 357–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Penas, R.; Verdugo-Escamilla, C.; Triunfo, C.; Gärtner, S.; D’Urso, A.; Oltolina, F.; Follenzi, A.; Maoloni, G.; Cölfen, H.; Falini, G.; et al. A sustainable one-pot method to transform seashell waste calcium carbonate to osteoinductive hydroxyapatite micro-nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 7766–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, M.; Sridhar, K.; Kanda, Y.; Yamanaka, S. Pure hydroxyapatite synthesis originating from amorphous calcium carbonate. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco, C.; Cancelo Hidalgo, M.J.; Palacios, S.; Ciria-Recasens, M.; Fernández-Pareja, A.; Carbonell-Abella, C.; Manasanch, J.; Haya-Palazuelos, J. Efficacy and safety of ossein-hydroxyapatite complex versus calcium carbonate to prevent bone loss. Climacteric 2020, 23, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Hossain, M.S.; Ahmed, S.; Bin Mobarak, M. Characterization and adsorption performance of nano-hydroxyapatite synthesized from Conus litteratus waste seashells for Congo red dye removal. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 38560–38577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Prasad, A.; Mulchandani, N.; Shah, M.; Ravi Sankar, M.; Kumar, S.; Katiyar, V. Multifunctional Nanohydroxyapatite-Promoted Toughened High-Molecular-Weight Stereocomplex Poly (lactic acid)-Based Bionanocomposite for Both 3D-Printed Orthopedic Implants and High-Temperature Engineering Applications. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 4039–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, C.; Gayathri, V.S.; Sowmya, S.V.; Augustine, D.; Alamoudi, A.; Zidane, B.; Hassan Mohammad Albar, N.; Bhandi, S. Nanohydroxyapatite in dentistry: A comprehensive review. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Madhubala, M.M.; Rajkumar, G.; Dhivya, V.; Kishen, A.; Srinivasan, N.; Mahalaxmi, S. Physico-chemical and biological characterization of synthetic and eggshell derived nanohydroxyapatite/carboxymethyl chitosan composites for pulp-dentin tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rujitanapanich, S.; Kumpapan, P.; Wanjanoi, P. Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite from Oyster Shell via Precipitation. Energy Procedia 2014, 56, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.F. Desenvolvimento de Biocerâmicas de Origem Fossilizada Para Reconstrução e Neoformação Óssea; Editora Appris: Curitiba, Brazil, 2019; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Barboza, A.; Dugaich, A.P.C.; Nörnberg, A.B.; de Moraes, S.C.; Santana, M.A.T.; da Silva, D.F.; de Campos, C.E.M.; Lund, R.G.; Ribeiro de Andrade, J.S. Development and characterization of nanofibrous scaffolds for guided periodontal regeneration using recycled mussel shell-derived nano-hydroxyapatite. Dent. Mater. 2025, 46, 1556–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Niero, A.L.; Possolli, N.M.; da Silva, D.F.; Demetrio, K.B.; Zocche, J.J.; de Souza, G.M.S.; Dias, J.F.; Vieira, J.L.; Barbosa, J.D.V.; Soares, M.B.P.; et al. Composite beads of alginate and biological hydroxyapatite from poultry and mariculture for hard tissue repair. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 25319–25332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.A. TOPAS and TOPAS-Academic: An optimization program integrating computer algebra and crystallographic objects written in C++. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2018, 51, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 2nd ed.; CLSI supplement M60; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed.; CLSI standard M07; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices-Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Bauer, Y.G.; Magini, E.B.; Farias, I.V.; Della Pasqua Neto, J.; Fongaro, G.; Reginatto, F.H.; Silva, I.T.; Cruz, A.C.C. Potential of Cranberry to Stimulate Osteogenesis: An In vitro Study. Coatings 2024, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Lozano, N.; Apátiga-Castro, M.; Soto, K.M.; Manzano-Ramírez, A.; Zamora-Antuñano, M.; Gonzalez-Gutierrez, C. Effect of temperature on crystallite size of hydroxyapatite powders obtained by wet precipitation process. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2022, 26, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, E.; Tampieri, A.; Celotti, G.; Sprio, S. Densification behavior and mechanisms of synthetic hydroxyapatites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 20, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, V.H.J.M.; Pontin, D.; Ponzi, G.G.D.; Stepanha, A.S.D.G.; Martel, R.B.; Schütz, M.K.; Dalla Vecchia, F. Application of Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) coupled with multivariate regression for calcium carbonate (CaCO3) quantification in cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 313, 125413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasingam, S.; Venkatachalapathy, R. Estimation of Carbonate Concentration and Characterization of Marine Sediments by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2014, 66, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahana, H.; Khajuria, D.K.; Razdan, R.; Mahapatra, D.R.; Bhat, M.R.; Suresh, S.; Rao, R.R.; Mariappan, L. Improvement in Bone Properties by Using Risedronate Adsorbed Hydroxyapatite Novel Nanoparticle Based Formulation in a Rat Model of Osteoporosis. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 9, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunadasa, K.S.P.; Manoratne, C.H.; Pitawala, H.M.T.G.A.; Rajapakse, R.M.G. Thermal Decomposition of Calcium Carbonate (Calcite Polymorph) as Examined by In-Situ High-Temperature X-ray Powder Diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 134, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloshchapov, D.L.; Savchenko, D.V.; Kashkarov, V.M.; Khmelevskiy, N.O.; Aksenenko, A.Y.; Seredin, P.V. Study of the dependence of the structural defects and bulk inhomogeneities of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite on the conditions of production using a biological source of calcium. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1400, 033008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, S.; Zec, S.; Miljević, N.; Milonjić, S. The Effect of Temperature on the Properties of Hydroxyapatite Precipitated from Calcium Hydroxide and Phosphoric Acid. Thermochim. Acta 2001, 374, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Maity, S.; Chabri, S.; Bera, S.; Chowdhury, A.R.; Das, M.; Sinha, A. Mechanochemical synthesis of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite from Mercenaria clam shells and phosphoric acid. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2017, 3, 015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestari, F.; Agostinacchio, F.; Galotta, A.; Chemello, G.; Motta, A.; Sglavo, V.M. Nano-Hydroxyapatite Derived from Biogenic and Bioinspired Calcium Carbonates: Synthesis and In vitro Bioactivity. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.; Vikulina, A.S.; Volodkin, D. CaCO3 crystals as versatile carriers for controlled delivery of antimicrobials. J. Control. Release 2020, 328, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memar, M.Y.; Ahangarzadeh Rezaee, M.; Barzegar-Jalali, M.; Gholikhani, T.; Adibkia, K. The Antibacterial Effect of Ciprofloxacin Loaded Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Nanoparticles Against the Common Bacterial Agents of Osteomyelitis. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidykhan, L.; Abu Bakar, M.Z.; Rukayadi, Y.; Kura, A.U.; Latifah, S.Y. Development of nanoantibiotic delivery system using cockle shell-derived aragonite nanoparticles for treatment of osteomyelitis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M.; Daglilar, S.; Kuskonmaz, N.; Kalkandelen, C.; Erdemir, G.; Kuruca, S.E.; Tulyaganov, D.; Yoshioka, T.; Gunduz, O.; Ficai, D.; et al. Mechanical and Biocompatibility Properties of Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics Derived from Salmon Fish Bone Wastes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Álvarez, M.; González, P.; Serra, J.; Fraguas, J.; Valcarcel, J.; Vázquez, J.A. Chondroitin sulfate and hydroxyapatite from Prionace glauca shark jaw: Physicochemical and structural characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu-Pelin, G.; Ristoscu, C.; Duta, L.; Pasuk, I.; Stan, G.E.; Stan, M.S.; Popa, M.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Hapenciuc, C.; Oktar, F.N.; et al. Fish Bone Derived Bi-Phasic Calcium Phosphate Coatings Fabricated by Pulsed Laser Deposition for Biomedical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Phases | Phase Fraction (%wt) | Lattice (Å) | Cry Size (nm) | Strain G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 CaCO3 | Aragonite Pmcn (62) | 96.12 (10) | a = 4.96575 (11) | 76.7 (7) | 0.0 (2) |

| b = 7.96972 (17) | |||||

| c = 5.74970 (10) | |||||

| Calcite R-3cH (167) | 3.88 (10) | a = 4.9893 (7) | 60 (5) | 0 (4) | |

| c = 17.056 (3) | |||||

| #1 HA | Degree of crystallinity (%) | 75.28 | - | - | - |

| Hydroxyapatite P63/m (176) | 86.3 (2) | a = 9.4283 (3) | 83.0 (12) | 0.152 (7) | |

| c = 6.8874 (3) | |||||

| β-TCP R-3cH (161) | 13.2 (2) | a = 10.4393 (6) | 167 (16) | 0.122 (16) | |

| c = 37.330 (3) | |||||

| Brushite Ia (9) | 0.52 (10) | a = 5.815 (15) | 0 (110,000) | 0.18 (11) |

| Particles | Zeta Potential (mV) | Particle Size Z-Ave (d·nm) | Mobility (µm·cm/V·s) | Conductivity (mS/cm) | PdI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaCO3 | −18.00 ± 0.40 | 410.50 ± 17.04 | −1.414 ± 0.031 | 0.05783 ± 0.00070 | 0.603 ± 0.150 |

| HA | −18.47 ± 1.09 | 179.73 ± 20.24 | −1.447 ± 0.084 | 0.02543 ± 0.00031 | 0.744 ± 0.074 |

| Property | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Purity degree | % | ~65–72 |

| Crystallinity | % | ~75–83 |

| pH (10% solution) | – | 7.0–8.0 |

| Surface area | m2/g | 2.5–5.0 |

| Crystallite size | Nm | ~60 |

| Oxide residues (R2O3) | % | ~7.16 |

| HA 900 (TGA) | wt% | 1004.62 |

| Density | g/cm3 | 3.09–3.30 |

| Microorganisms | CaCO3 | HA |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | >100 mg/mL | >100 mg/mL |

| S. mutans | >100 mg/mL | >100 mg/mL |

| E. faecalis | >100 mg/mL | >100 mg/mL |

| C. albicans | >100 mg/mL | >100 mg/mL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dugaich, A.P.C.; Barboza, A.d.S.; Silva, M.G.e.; Nörnberg, A.B.; Maraschin, M.; Badaró, M.M.; Silva, D.F.d.; Campos, C.E.M.d.; Santinoni, C.d.S.; Stolf, S.C.; et al. Sustainable Valorization of Mussel Shell Waste: Processing for Calcium Carbonate Recovery and Hydroxyapatite Production. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010024

Dugaich APC, Barboza AdS, Silva MGe, Nörnberg AB, Maraschin M, Badaró MM, Silva DFd, Campos CEMd, Santinoni CdS, Stolf SC, et al. Sustainable Valorization of Mussel Shell Waste: Processing for Calcium Carbonate Recovery and Hydroxyapatite Production. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleDugaich, Adriana Poli Castilho, Andressa da Silva Barboza, Marianna Gimenes e Silva, Andressa Baptista Nörnberg, Marcelo Maraschin, Maurício Malheiros Badaró, Daiara Floriano da Silva, Carlos Eduardo Maduro de Campos, Carolina dos Santos Santinoni, Sheila Cristina Stolf, and et al. 2026. "Sustainable Valorization of Mussel Shell Waste: Processing for Calcium Carbonate Recovery and Hydroxyapatite Production" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010024

APA StyleDugaich, A. P. C., Barboza, A. d. S., Silva, M. G. e., Nörnberg, A. B., Maraschin, M., Badaró, M. M., Silva, D. F. d., Campos, C. E. M. d., Santinoni, C. d. S., Stolf, S. C., Lund, R. G., & Andrade, J. S. R. d. (2026). Sustainable Valorization of Mussel Shell Waste: Processing for Calcium Carbonate Recovery and Hydroxyapatite Production. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010024