Engineering Self-Assembled PEEK Scaffolds with Marine-Derived Exosomes and Bacteria-Targeting Aptamers for Enhanced Antibacterial Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

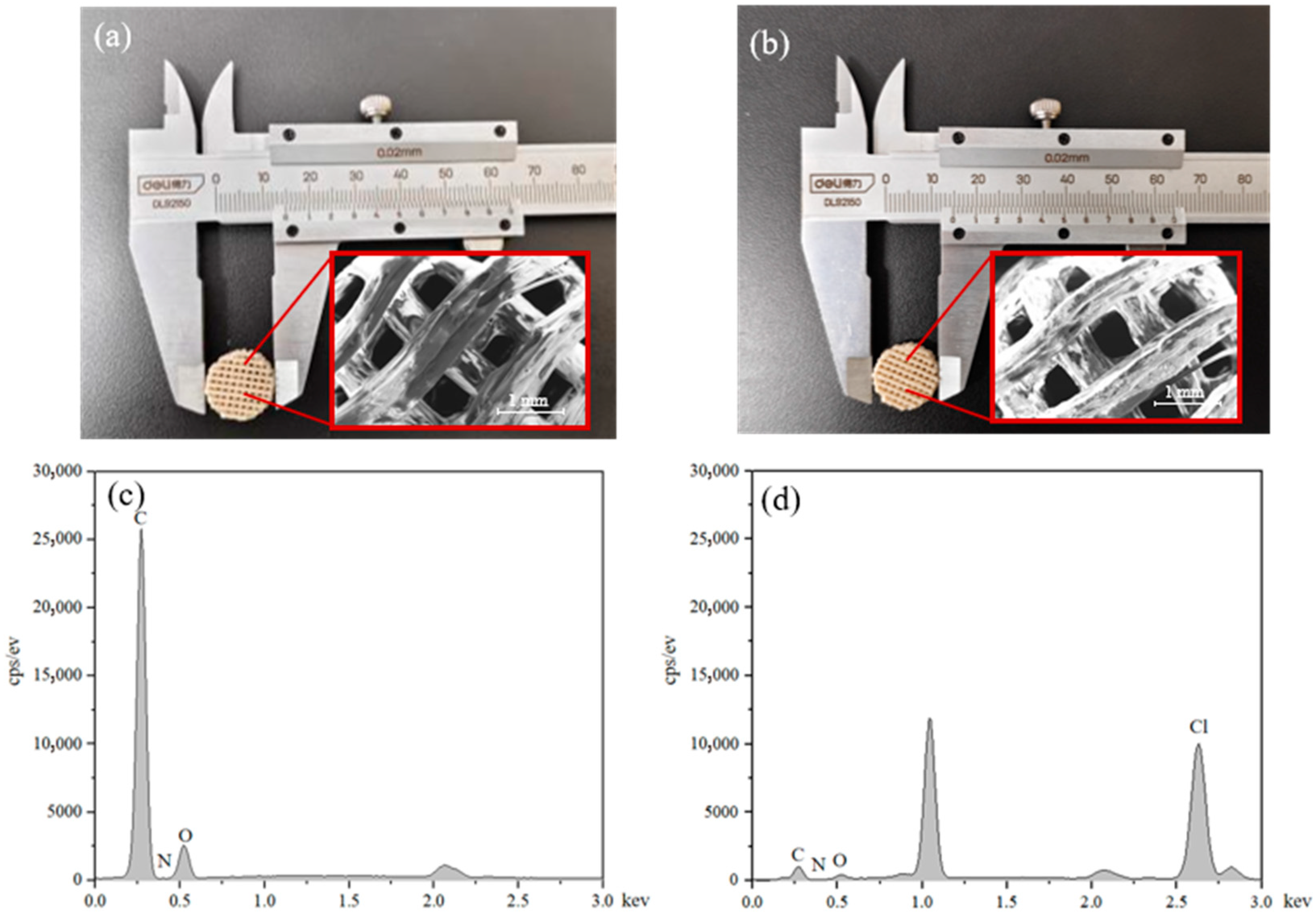

2.1. Morphology Observations

2.2. SEM Characterization of Scaffolds

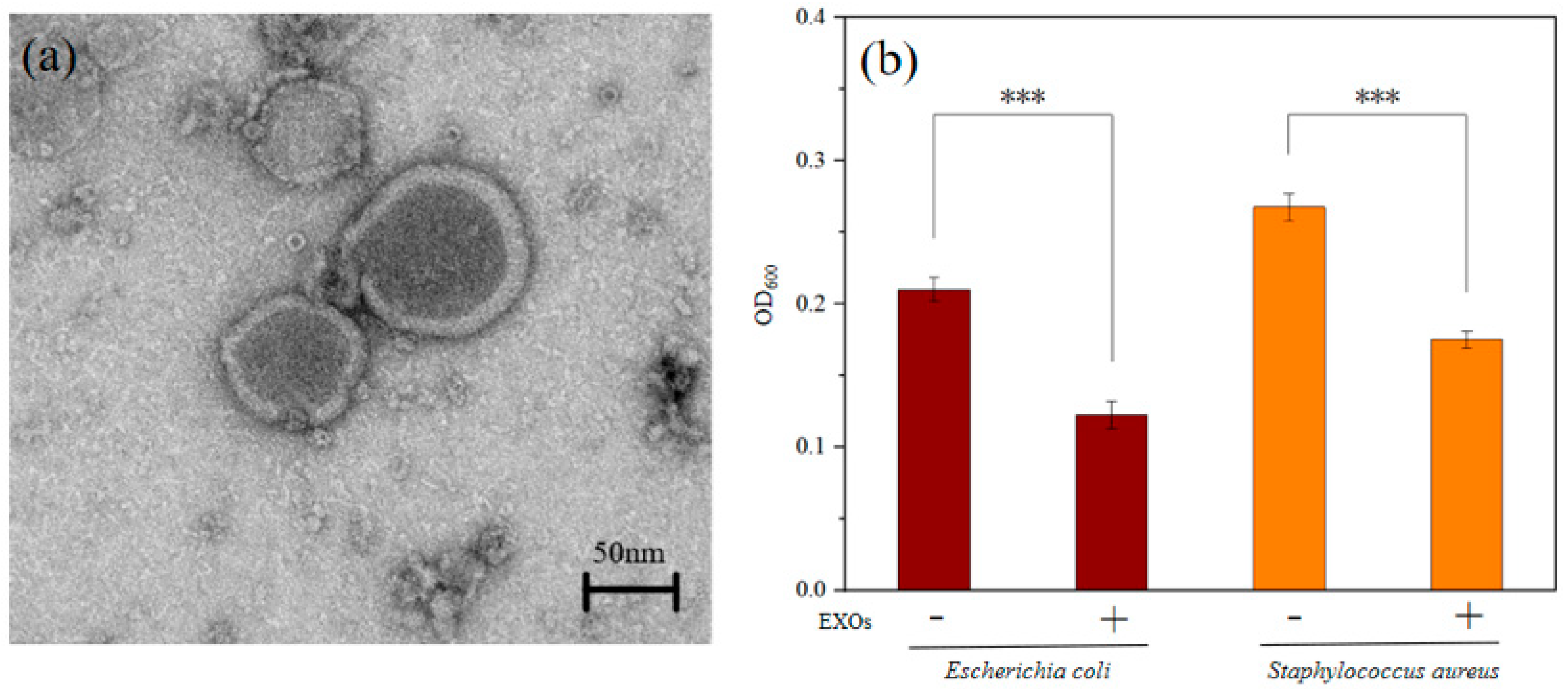

2.3. Antibacterial Activity of EXOs

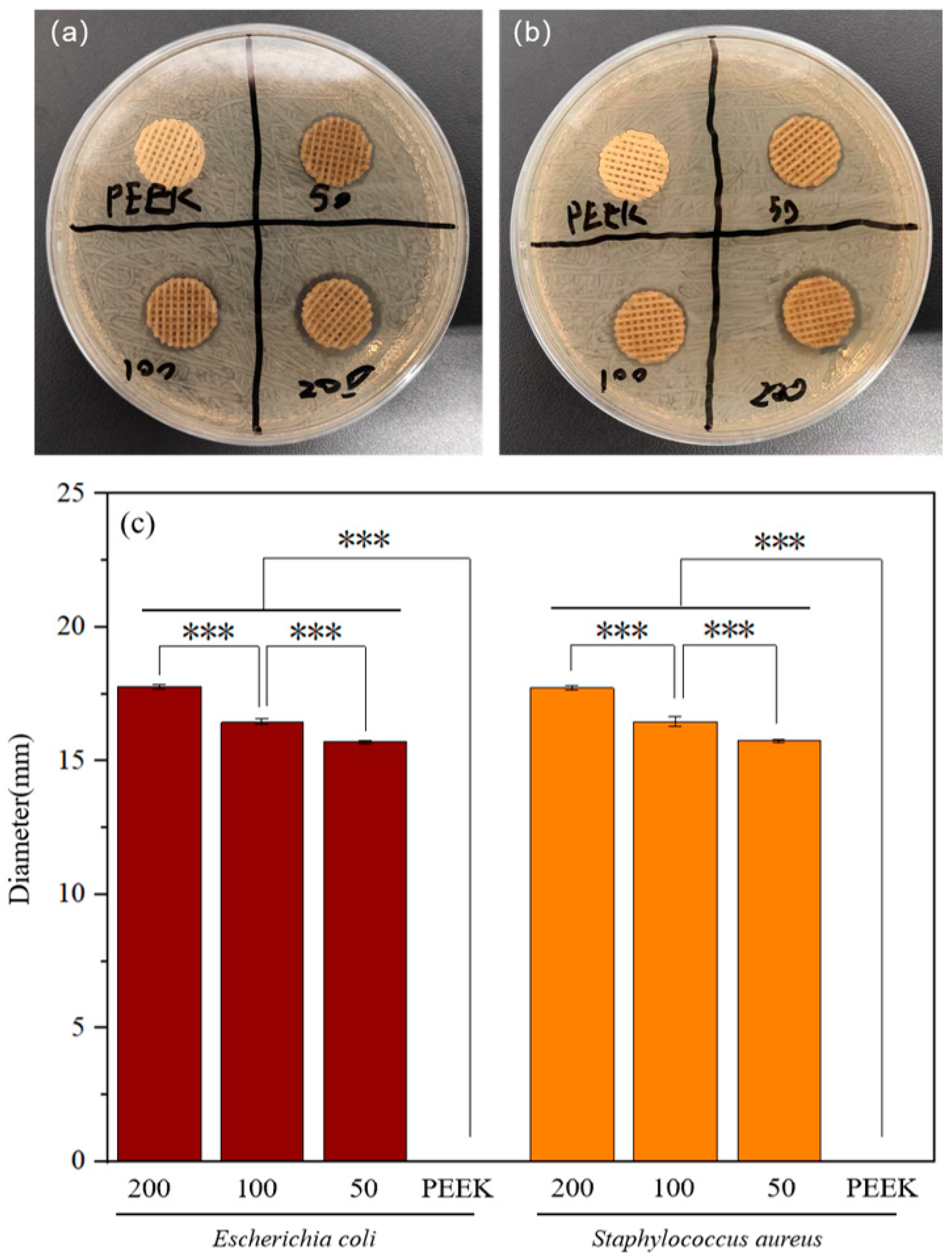

2.4. Antibacterial Performance of Modified Scaffolds

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of PEEK Scaffolds and PDA Modification

4.2. Isolation and Characterization of EXOs

4.3. Preparation of PEEK Scaffolds Loaded with Antibacterial Coatings (PEEK-PDA-EXOs-Apt)

4.4. Morphological Characterization of Modified Scaffolds

4.5. Examination Antibacterial Activity of EXOs via Absorption Photometry

4.6. Absorption Method for Testing Antibacterial Activity

4.7. Antibacterial Zone Test

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EXOs | Exosomes |

| Apt | Aptamer |

| PEEK | Polyetheretherketone |

| PDA | Polydopamine |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscope |

| DA | Dopamine |

References

- Liang, H.; Fu, G.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. A 3D-printed Sn-doped calcium phosphate scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 1016820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, K.M. 1—Introduction to the challenges of bone repair. In Bone Repair Biomaterials, 2nd ed.; Pawelec, K.M., Planell, J.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, K.; Chen, S.; Senthooran, V.; Hu, X.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, L.; Wang, J. Microporous polylactic acid/chitin nanocrystals composite scaffolds using in-situ foaming 3D printing for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, F.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.; Shao, Z.; Li, C.; Feng, J.; Xue, L.; Chen, F. Research and Application of Medical Polyetheretherketone as Bone Repair Material. Macromol. Biosci. 2023, 23, e2300032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Ru, Y.; You, J.; Lin, R.; Chen, S.; Qi, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, Z. Antibacterial Properties of PCL@45s5 Composite Biomaterial Scaffolds Based on Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2024, 16, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr Azadani, M.; Zahedi, A.; Bowoto, O.K.; Oladapo, B.I. A review of current challenges and prospects of magnesium and its alloy for bone implant applications. Prog. Biomater. 2022, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cai, W.-j.; Ren, Z.; Han, P. The Role of Staphylococcal Biofilm on the Surface of Implants in Orthopedic Infection. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yin, R.; Cheng, J.; Lin, J. Bacterial Biofilm Formation on Biomaterials and Approaches to Its Treatment and Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayotov, I.V.; Orti, V.; Cuisinier, F.; Yachouh, J. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) for medical applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2016, 27, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, E.; Li, H.; Cerruti, M. Surface Modification Strategies to Improve the Osseointegration of Poly(etheretherketone) and Its Composites. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, 1900271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Chowdhary, R. PEEK materials as an alternative to titanium in dental implants: A systematic review. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.-G.; Park, K.-M.; Lee, J.-A.; Nam, J.-H.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kang, K.-T. Total knee arthroplasty application of polyetheretherketone and carbon-fiber-reinforced polyetheretherketone: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 100, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Ding, X.; Huang, R.; Jiang, R.; Huang, H.; Pan, X.; Min, W.; Chen, J.; Duan, J.-A.; Liu, P.; et al. Bone Tissue Engineering in the Treatment of Bone Defects. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Suonan, A.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhao, X.; Lou, X.; Yang, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.-g. PEEK (Polyether-ether-ketone) and its composite materials in orthopedic implantation. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 102977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrubudin, N.; Lee, T.C.; Ramlan, R. An Overview on 3D Printing Technology: Technological, Materials, and Applications. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 35, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Sansi Seukep, A.M.; Senthooran, V.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J. Progress of Polymer-Based Dielectric Composites Prepared Using Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Y.; Karayel, E. 3D printing technology; methods, biomedical applications, future opportunities and trends. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 1430–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimar, A.; Palermo, A.; Innocenti, B. The Role of 3D Printing in Medical Applications: A State of the Art. J. Healthc. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5340616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Gou, J.; Hui, D. 3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, K.; Guo, H.; He, M.; Shi, X.; Guo, Y.; Kong, J.; Gu, J. Advances in 3D printing for polymer composites: A review. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Thirunavukkarasu, N.; Mubarak, S.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, L. Preparation of Thermoplastic Polyurethane/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Composite Foam with High Resilience Performance via Fused Filament Fabrication and CO2 Foaming Technique. Polymers 2023, 15, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Zahedi, S.A.; Ismail, S.O.; Omigbodun, F.T.; Bowoto, O.K.; Olawumi, M.A.; Muhammad, M.A. 3D printing of PEEK–cHAp scaffold for medical bone implant. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2021, 4, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, C.; Sun, C.; Yan, X.; He, J.; Shi, C.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Jiang, T.; Huang, L. Fused Deposition Modeling PEEK Implants for Personalized Surgical Application: From Clinical Need to Biofabrication. Int. J. Bioprinting 2022, 8, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, J.M. Chapter 8—Biocompatibility of PEEK Polymers. In PEEK Biomaterials Handbook, 2nd ed.; Kurtz, S.M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Gabriel, M.; Schmidt, F.; Müller, W.-D.; Schwitalla, A.D. The impact of different low-pressure plasma types on the physical, chemical and biological surface properties of PEEK. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e15–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Zahedi, S.A.; Ismail, S.O.; Omigbodun, F.T. 3D printing of PEEK and its composite to increase biointerfaces as a biomedical material- A review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 203, 111726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullan, R.; Golbang, A.; Salma-Ancane, K.; Ward, J.; Rodzen, K.; Boyd, A.R. Review of 3D Printing of Polyaryletherketone/Apatite Composites for Lattice Structures for Orthopedic Implants. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Luo, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Gong, B.; Li, Z.; Sun, H. Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2024, 63, 20240025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Golbang, A.; Jindal, S.; Dixon, D.; McIlhagger, A.; Harkin-Jones, E.; Crawford, D.; Mancuso, E. 3D printed PEEK/HA composites for bone tissue engineering applications: Effect of material formulation on mechanical performance and bioactive potential. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 121, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhao, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Kang, J.; Yang, C.; Sun, C.; Xiong, M.; Fu, M.; Jin, D.; et al. Additively-manufactured PEEK/HA porous scaffolds with excellent osteogenesis for bone tissue repairing. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 232, 109508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Guo, H.; Zhong, L.; Wang, M.; Xue, P.; Yuan, X. Influence of surface-modified glass fibers on interfacial properties of GF/PEEK composites using molecular dynamics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 188, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, E.; Caglar, I. Enhancing PEEK bond strength: The impact of chemical and mechanical surface modifications on surface characteristics and phase transformation. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.; Matos, J.; Afonso, C. Extraction of Marine Bioactive Compounds from Seaweed: Coupling Environmental Concerns and High Yields. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, D.S.; Raja, A.B.; Nachimuthu, S.; Thangavel, S.; Kannan, K.; Shanmugan, S.; Tari, V. Exploration of Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties, and Their Potential Efficacy Against HT29 Cell Lines in Dictyota bartayresiana. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gao, J.; Wu, X.; Hao, X.; Hu, W.; Han, L. Conductive Microneedles Loaded with Polyphenol-Engineered Exosomes Reshape Diabetic Neurovascular Niches for Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e07974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Q.; Liu, T.L.; Liang, P.H.; Zhang, S.H.; Li, T.S.; Li, Y.P.; Liu, G.X.; Mao, L.; Luo, X.N. Characterization of exosome-like vesicles derived from Taenia pisiformis cysticercus and their immunoregulatory role on macrophages. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosazadeh Moghaddam, M.; Fazel, P.; Fallah, A.; Sedighian, H.; Kachuei, R.; Behzadi, E.; Imani Fooladi, A.A. Host and Pathogen-Directed Therapies against Microbial Infections Using Exosome- and Antimicrobial Peptide-derived Stem Cells with a Special look at Pulmonary Infections and Sepsis. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2023, 19, 2166–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.; Hu, R.; Runtsch, M.C.; Kagele, D.A.; Mosbruger, T.L.; Tolmachova, T.; Seabra, M.C.; Round, J.L.; Ward, D.M.; O’Connell, R.M. Exosome-delivered microRNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; Bao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, L. Exosomes in Pathogen Infections: A Bridge to Deliver Molecules and Link Functions. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, A.; D’Amico, R.; Lanzetta, R.; Corsaro, M.M. Marine Delivery Vehicles: Molecular Components and Applications of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léguillier, V.; Heddi, B.; Vidic, J. Recent Advances in Aptamer-Based Biosensors for Bacterial Detection. Biosensors 2024, 14, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.M.; de Sousa Lacerda, C.M.; dos Santos, S.R.; de Barros, A.L.B.; Fernandes, S.O.; Cardoso, V.N.; de Andrade, A.S.R. Detection of bacterial infection by a technetium-99m-labeled peptidoglycan aptamer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, H.; Tian, R.; Guo, S.; Liao, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, B. A DNA Origami-based Bactericide for Efficient Healing of Infected Wounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202311698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didarian, R.; Ozbek, H.K.; Ozalp, V.C.; Erel, O.; Yildirim-Tirgil, N. Enhanced SELEX Platforms for Aptamer Selection with Improved Characteristics: A Review. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 2962–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.L.; Woodrow, K.A. Medical Applications of Porous Biomaterials: Features of Porosity and Tissue-Specific Implications for Biocompatibility. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2102087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, S.; Buccino, F.; Qin, Z.; Vergani, L.M. Structural influences on bone tissue engineering: A review and perspective. Matter 2025, 8, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhu, M.; Qiu, Q.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, C.; Bai, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Lu, T. The contribution of pore size and porosity of 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds to osteogenesis. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 133, 112651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Dellatore, S.M.; Miller, W.M.; Messersmith, P.B. Mussel-Inspired Surface Chemistry for Multifunctional Coatings. Science 2007, 318, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Mu, J.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Lin, H.; Cao, J.; Gao, J. An antioxidative sophora exosome-encapsulated hydrogel promotes spinal cord repair by regulating oxidative stress microenvironment. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2023, 47, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Z.-X.; Lin, X.-Y.; Wu, Z.-R.; Zhong, X.-C.; Zhuang, Z.-M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Tan, W.-Q. Recent Development and Applications of Polydopamine in Tissue Repair and Regeneration Biomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 859–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Ding, Y.; Tao, B.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Cai, K. Surface modification of titanium substrate via combining photothermal therapy and quorum-sensing-inhibition strategy for improving osseointegration and treating biofilm-associated bacterial infection. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Liang, X.; Chen, F.; Ke, M.; Yang, X.; Ai, J.; Cheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. Injectable shape memory hydroxyethyl cellulose/soy protein isolate based composite sponge with antibacterial property for rapid noncompressible hemorrhage and prevention of wound infection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Gao, W.; Li, J.; Pu, Y.; He, B.; Xie, J. A Mg2+/polydopamine composite hydrogel for the acceleration of infected wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 15, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, D.T.A.; Alqarni, A.S.; Almohammadi, A.M.; Abujamel, T.; Shaala, L.A. Marmaricines A-C: Antimicrobial Brominated Pyrrole Alkaloids from the Red Sea Marine Sponge Agelas sp. aff. marmarica. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, P.; Taghavi, E.; Foong, S.Y.; Rajaei, A.; Amiri, H.; de Tender, C.; Peng, W.; Lam, S.S.; Aghbashlo, M.; Rastegari, H.; et al. Comparison of shrimp waste-derived chitosan produced through conventional and microwave-assisted extraction processes: Physicochemical properties and antibacterial activity assessment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.M.; Yousuf, W.E.; Kenawy, E.-R.; Mohamed, T.M. Biosynthesis of cellulose from Ulva lactuca, manufacture of nanocellulose and its application as antimicrobial polymer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lu, N.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Z. Specific capture, detection, and killing of Enterococcus faecalis based on aptamer-modified peroxidase mimetic nanozymes. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 161848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgenfrei, M.; Hürlimann, L.M.; Remy, M.M.; Keller, P.M.; Seeger, M.A. Biomolecules capturing live bacteria from clinical samples. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatah, S.A.; Omer, K.M. Aptamer-Modified MOFs (Aptamer@MOF) for Efficient Detection of Bacterial Pathogens: A Review. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 11578–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; You, J.; Lin, R.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, H.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. Engineering Self-Assembled PEEK Scaffolds with Marine-Derived Exosomes and Bacteria-Targeting Aptamers for Enhanced Antibacterial Functions. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010023

Zhang C, You J, Lin R, Ye Y, Cheng C, Wang H, Li D, Wang J, Chen S. Engineering Self-Assembled PEEK Scaffolds with Marine-Derived Exosomes and Bacteria-Targeting Aptamers for Enhanced Antibacterial Functions. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chen, Jinchao You, Runyi Lin, Yuansong Ye, Chuchu Cheng, Haopeng Wang, Dejing Li, Junxiang Wang, and Shan Chen. 2026. "Engineering Self-Assembled PEEK Scaffolds with Marine-Derived Exosomes and Bacteria-Targeting Aptamers for Enhanced Antibacterial Functions" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010023

APA StyleZhang, C., You, J., Lin, R., Ye, Y., Cheng, C., Wang, H., Li, D., Wang, J., & Chen, S. (2026). Engineering Self-Assembled PEEK Scaffolds with Marine-Derived Exosomes and Bacteria-Targeting Aptamers for Enhanced Antibacterial Functions. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010023