The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite and Its Influence on the Cellular Response to Biomaterials: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- P (population) = osteoblastic or bone cells;

- E (exposition) = direct or indirect exposure to calcium phosphates doped with zinc;

- C (comparison) = calcium phosphates not containing zinc;

- O (outcome) = biocompatibility, proliferation, differentiation, mineralization, and gene expression;

- S (setting) = in vitro tests.

2.2. Selection of Articles

2.3. Quality Assessment of the Selected Studies

2.4. Data Extraction and Qualitative Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Database Search

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Characteristics of Selected Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite

4.2. Solubility and the Release of Zn2+

4.3. Cell Adhesion into ZnHA Surfaces

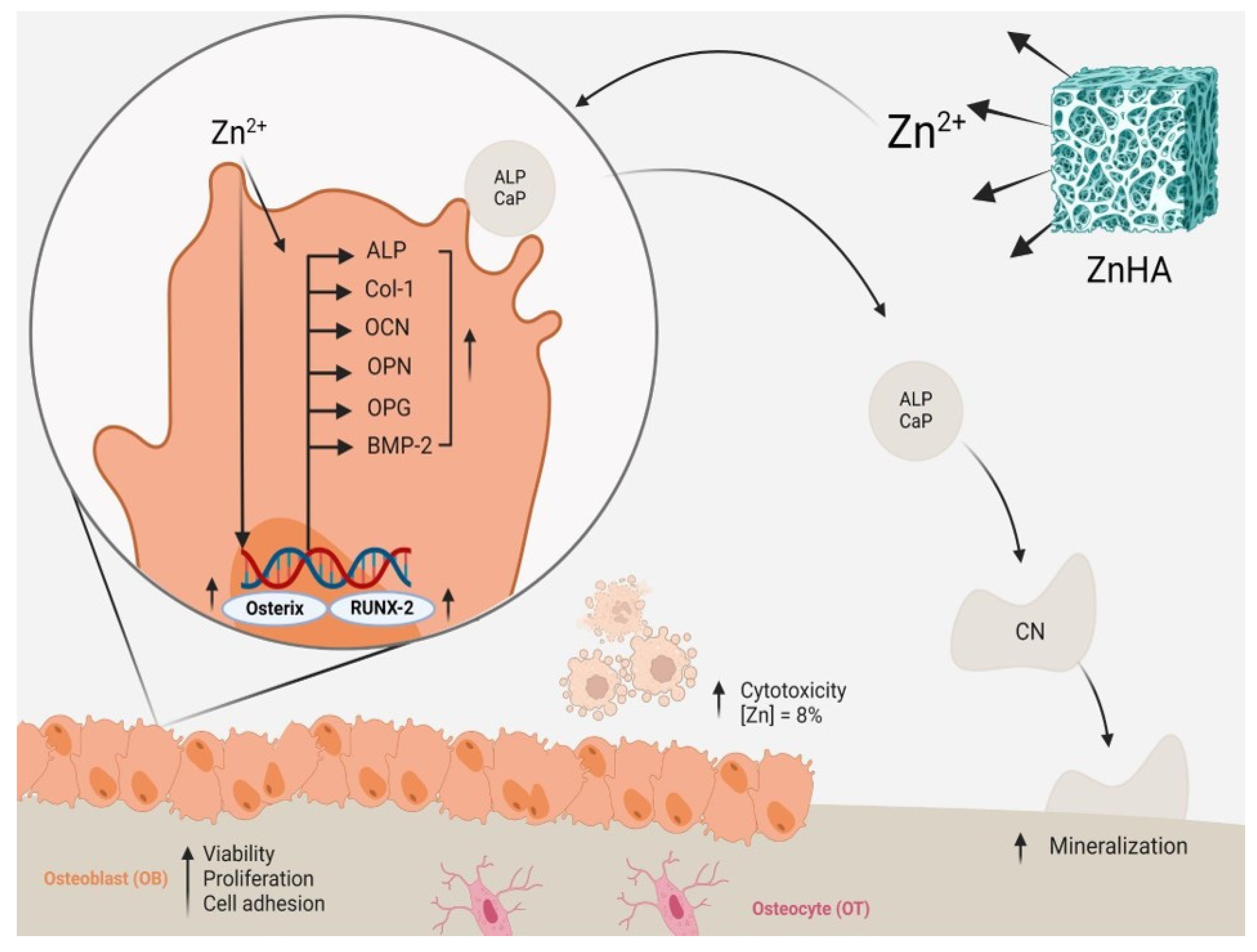

4.4. Effects on Cytocompatibility

4.5. Effects on Cell Proliferation

4.6. Effects on Cell Differentiation and In Vitro Mineralization

4.7. Other Biological Effects

4.8. Summary of Evidence and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Yang, R.; Cooper, P.R.; Khurshid, Z.; Shavandi, A.; Ratnayake, J. Bone Grafts and Substitutes in Dentistry: A Review of Current Trends and Developments. Molecules 2021, 26, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.H. Autologous bone graft: Is it still the gold standard? Injury 2021, 52 (Suppl. S2), S18–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, T.E.; Mathew, P.J.; Plotsker, E.L.; Sevilla, A.C.; Thaller, S.R. Biomaterials in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction: Past, Present, and Future. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendi, F.; Abdullah, B.; Suryani, S.; Usman, A.N.; Tahir, D. Development and application of hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration: A systematic literature review. Bone 2024, 183, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, D.; Sartoretto, S.C.; Calasans-Maia, J.d.A.; Ghiraldini, B.; Bezerra, F.J.B.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Calasans-Maia, M.D. In vivo osseointegration evaluation of implants coated with nanostructured hydroxyapatite in low density bone. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Ginebra, M.P.; Engel, E.; Planell, J. Ion reactivity of calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite in standard cell culture media. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 4242–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, A.; Žužić, A.; Ivanišević, I.; Kamboj, N.; Ivanković, H. Ionic substituted hydroxyapatite for bone regeneration applications: A review. Open Ceram. 2021, 6, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cockerill, I.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.-X.; Chang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, D. Zinc-Based Biomaterials for Regeneration and Therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zastulka, A.; Clichici, S.; Tomoaia-Cotisel, M.; Mocanu, A.; Roman, C.; Olteanu, C.D.; Culic, B.; Mocan, T. Recent Trends in Hydroxyapatite Supplementation for Osteoregenerative Purposes. Materials 2023, 16, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, A.; Güldal, N.S.; Boccaccini, A.R. A review of the biological response to ionic dissolution products from bioactive glasses and glass-ceramics. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2757–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwitonze, A.M.; Ojeh, N.; Murererehe, J.; Atfi, A.; Razzaque, M.S. Zinc Adequacy Is Essential for the Maintenance of Optimal Oral Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.; Calasans-Maia, J.; Sartoretto, S.; Moraschini, V.; Rossi, A.M.; Louro, R.S.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Calasans-Maia, M.D. Does the incorporation of zinc into calcium phosphate improve bone repair? A systematic review. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Zelaya, V.R.; Zarranz, L.; Herrera, E.Z.; Alves, A.T.; Uzeda, M.J.; Mavropoulos, E.; Rossi, A.L.; Mello, A.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Calasans-Maia, M.D.; et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of nanocrystalline Zn-doped carbonated hydroxyapatite/alginate microspheres: Zinc and calcium bioavailability and bone regeneration. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3471–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Komuro, M.; Hao, J.; Kuroda, S.; Hattori, Y.; Ben-Nissan, B.; Milthorpe, B.; Otsuka, M. Bioresorbable zinc hydroxyapatite guided bone regeneration membrane for bone regeneration. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hamzah, E.; Ismail, A.F.; Aziz, M.; Daroonparvar, M.; Saebnoori, E.; Chami, A. In vitro degradation behavior, antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of TiO2-MAO/ZnHA composite coating on Mg alloy for orthopedic implants. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 334, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begam, H.; Kundu, B.; Chanda, A.; Nandi, S.K. MG63 osteoblast cell response on Zn doped hydroxyapatite (HAp) with various surface features. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 3752–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bose, S. Plasma sprayed fluoride and zinc doped hydroxyapatite coated titanium for load-bearing implants. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 440, 128464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, A.; Pramanik, N.; Manna, P.J.; Mitra, T.; Selvaraj, T.K.R.; Gnanamani, A.; Das, M.; Kundu, P.P. Development of porous and antimicrobial CTS–PEG–HAP–ZnO nano-composites for bone tissue engineering. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 99385–99393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, X.; Yang, J. Biomimetic injectable and bilayered hydrogel scaffold based on collagen and chondroitin sulfate for the repair of osteochondral defects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, V.; Thomas, J.; Sharma, A.; Panwar, V.; Kaushik, S.; Sharma, S.; Porwal, K.; Kulkarni, C.; Rajput, S.; Singh, H.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of a Zinc Eluting rGO/Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposite Optimized for Bone Augmentation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 6710–6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuozzo, R.C.; Sartoretto, S.C.; Resende, R.F.B.; Alves, A.T.N.N.; Mavropoulos, E.; da Silva, M.H.P.; Calasans-Maia, M.D. Biological evaluation of zinc-containing calcium alginate-hydroxyapatite composite microspheres for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2020, 108, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Pang, X. In vitro cytocompatibility and corrosion resistance of zinc-doped hydroxyapatite coatings on a titanium substrate. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittler, M.L.; Unalan, I.; Grünewald, A.; Beltrán, A.M.; Grillo, C.A.; Destch, R.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Boccaccini, A.R. Bioactive glass (45S5)-based 3D scaffolds coated with magnesium and zinc-loaded hydroxyapatite nanoparticles for tissue engineering applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 182, 110346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, L.; Sarda, S.; Torricelli, P.; Combes, C.; Brouillet, F.; Marsan, O.; Salamanna, F.; Fini, M.; Boanini, E.; Bigi, A. Multifunctionalization Modulates Hydroxyapatite Surface Interaction with Bisphosphonate: Antiosteoporotic and Antioxidative Stress Materials. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3429–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.M.; Kaffashi, B.; Shokrollahi, P.; Seyedjafari, E.; Ardeshirylajimi, A. PCL/chitosan/Zn-doped nHA electrospun nanocomposite scaffold promotes adipose derived stem cells adhesion and proliferation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 118, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Chen, X.; Cheng, K.; Weng, W.; Wang, H. Enhanced Osteogenic Activity of TiO2 Nanorod Films with Microscaled Distribution of Zn-CaP. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 6944–6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Robatto, B.; López-Álvarez, M.; Azevedo, A.; Dorado, J.; Serra, J.; Azevedo, N.; González, P. Pulsed laser deposition of copper and zinc doped hydroxyapatite coatings for biomedical applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 333, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.H.; Lee, B.S.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, Y.P.; Kuo, W.T.; Chen, I.H.; He, A.C.; Lai, C.H.; Tung, K.L.; Chen, Y.W. Vapor-Induced Pore-Forming Atmospheric-Plasma-Sprayed Zinc-, Strontium-, and Magnesium-Doped Hydroxyapatite Coatings on Titanium Implants Enhance New Bone Formation—An In Vivo and In Vitro Investigation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Qiang, L.; Fan, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, A.; Chang, D.; Li, J.; Sun, T.; Wang, Y.; Guo, R.; et al. 3D-printed tri-element-doped hydroxyapatite/polycaprolactone composite scaffolds with antibacterial potential for osteosarcoma therapy and bone regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierczak, P.; Kolmas, J.; Przekora, A. Biological Response to Macroporous Chitosan-Agarose Bone Scaffolds Comprising Mg- and Zn-Doped Nano-Hydroxyapatite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, S.; Xu, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z. In vitro biocompatibility study of calcium phosphate glass ceramic scaffolds with different trace element doping. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2012, 32, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, W. Zinc-Containing Hydroxyapatite Enhances Cold-Light-Activated Tooth Bleaching Treatment In Vitro. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6261248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, I.R.; Alves, G.G.; Soriano, C.A.; Campaneli, A.P.; Gasparoto, T.H.; Ramos, E.S.; de Sena, L.; Rossi, A.M.; Granjeiro, J.M. Understanding the impact of divalent cation substitution on hydroxyapatite: An in vitro multiparametric study on biocompatibility. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part A 2011, 98, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-T.; Huang, T.-C.; Lin, G.-S.; Chen, Y.-W.; Lee, B.-S.; Tung, K.-L. In Vitro Bioactivity and Antibacterial Activity of Strontium-, Magnesium-, and Zinc-Multidoped Hydroxyapatite Porous Coatings Applied via Atmospheric Plasma Spraying. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Sun, Q.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Guo, T.; Meng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J. Osteoconductivity of Zinc-Doped Calcium Phosphate Coating on a 3D-Printed Porous Implant. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2017, 7, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki-Ghaleh, H.; Siadati, M.H.; Fallah, A.; Koc, B.; Kavanlouei, M.; Khademi-Azandehi, P.; Moradpur-Tari, E.; Omidi, Y.; Barar, J.; Beygi-Khosrowshahi, Y.; et al. Antibacterial and Cellular Behaviors of Novel Zinc-Doped Hydroxyapatite/Graphene Nanocomposite for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavropoulos, E.; Hausen, M.; Costa, A.M.; Alves, G.; Mello, A.; Ospina, C.A.; Mir, M.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Rossi, A.M. The impact of the RGD peptide on osteoblast adhesion and spreading on zinc-substituted hydroxyapatite surface. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Wu, X.; Yao, R.; He, J.; Yao, W.; Wu, F. Effect of zinc substitution in hydroxyapatite coating on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation under osteoblast/osteoclast co-culture. Regen. Biomater. 2019, 6, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’sullivan, C.; O’Hare, P.; O’Leary, N.D.; Crean, A.M.; Ryan, K.; Dobson, A.D.W.; O’Neill, L. Deposition of substituted apatites with anticolonizing properties onto titanium surfaces using a novel blasting process. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 95, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Oshita, M.; Kataoka, M.; Azuma, Y.; Furuzono, T. Shareability of antibacterial and osteoblastic-proliferation activities of zinc-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predoi, D.; Iconaru, S.L.; Ciobanu, C.S.; Raita, M.S.; Ghegoiu, L.; Trusca, R.; Badea, M.L.; Cimpeanu, C. Studies of the Tarragon Essential Oil Effects on the Characteristics of Doped Hydroxyapatite/Chitosan Biocomposites. Polymers 2023, 15, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.H.; Valerio, P.; Goes, A.M.; Leite, M.F.; Heneine, L.G.D.; Mansur, H.S. Biocompatibility evaluation of hydroxyapatite/collagen nanocomposites doped with Zn+2. Biomed. Mater. 2007, 2, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.H.; Heneine, L.G.D.; Mansur, H.S. Synthesis and characterization of calcium phosphate/collagen biocomposites doped with Zn2+. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thian, E.S.; Konishi, T.; Kawanobe, Y.; Lim, P.N.; Choong, C.; Ho, B.; Aizawa, M. Zinc-substituted hydroxyapatite: A biomaterial with enhanced bioactivity and antibacterial properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, I.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, A.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Shawish, I.; Bououdina, M.; Zuo, W. Physicochemical Properties and Simulation of Magnesium/Zinc Binary-Substituted Hydroxyapatite with Enhanced Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Ability. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 5349–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarmathi, N.; Sumathi, S. Zinc substituted hydroxyapatite/silk fiber/methylcellulose nanocomposite for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 214, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Xuan, L.; Zhong, H.; Gong, Y.; Shi, X.; Ye, F.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Q. Incorporation of well-dispersed calcium phosphate nanoparticles into PLGA electrospun nanofibers to enhance the osteogenic induction potential. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 23982–23993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ito, A.; Sogo, Y.; Li, X.; Oyane, A. Zinc-containing apatite layers on external fixation rods promoting cell activity. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.J.; Massa-Schlueter, E.A.; Smith, J.L.; Slamovich, E.B. Osteoblast response to hydroxyapatite doped with divalent and trivalent cations. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.J.; Ergun, C.; Doremus, R.H.; Bizios, R. Hydroxylapatite with substituted magnesium, zinc, cadmium, and yttrium. II. Mechanisms of osteoblast adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002, 59, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Dong, W.-J.; He, F.-M.; Wang, X.-X.; Zhao, S.-F.; Yang, G.-L. Osteoblast response to porous titanium surfaces coated with zinc-substituted hydroxyapatite. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012, 113, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J. Biocompatibility and Anti-Bacterial Activity of Zn-Containing HA/TiO2 Hybrid Coatings on Ti Substrate. J. Hard. Tissue Biol. 2013, 22, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Ma, J. Fabrication, characterization, and in vitro study of zinc substituted hydroxyapatite/silk fibroin composite coatings on titanium for biomedical applications. J. Biomater. Appl. 2017, 32, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lala, S.; Ghosh, M.; Das, P.K.; Das, D.; Kar, T.; Pradhan, S.K. Structural and microstructural interpretations of Zn-doped biocompatible bone-like carbonated hydroxyapatite synthesized by mechanical alloying. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, J.T.B.; Mucalo, M.; Dias, G.J. Substituted hydroxyapatites for bone regeneration: A review of current trends. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2017, 105, 1285–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, M.; Terra, J.; Ellis, D.E. Mechanism of Zn stabilization in hydroxyapatite and hydrated (0 0 1) surfaces of hydroxyapatite. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2010, 22, 145502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Escudero, A.; Espanol, M.; Beats, S.; Ginebra, M.P. In vitro degradation of calcium phosphates: Effect of multiscale porosity, textural properties and composition. Acta Biomater. 2017, 60, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calasans-Maia, M.D.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Rossi, A.M.; Alves, G.G. Cytocompatibility and biocompatibility of nanostructured carbonated hydroxyapatite spheres for bone repair. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.; Tanaka, M. Designing Smart Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, C.; Adam, J.; Kruppke, B.; Hintze, V.; Wiesmann, H.P.; Hanke, T. How to Get Them off? Assessment of Innovative Techniques for Generation and Detachment of Mature Osteoclasts for Biomaterial Resorption Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüdrich, U.; Lasgorceix, M.; Champion, E.; Pascaud-Mathieu, P.; Damia, C.; Chartier, T.; Brie, J.; Magnaudeix, A. Pre-osteoblast cell colonization of porous silicon substituted hydroxyapatite bioceramics: Influence of microporosity and macropore design. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 97, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.F. A Paradigm for the Evaluation of Tissue-Engineering Biomaterials and Templates. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2017, 23, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, H.; Mei, G.; Chen, S.; Ma, B.; Zhu, R. Application of Bioactive Materials for Osteogenic Function in Bone Tissue Engineering. Small Methods 2024, e2301283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, C.L.; Bartha, C.M.; Albu, M.; Guégan, R.; Motelica-Heino, M.; Chifiriuc, C.M.; Bleotu, C.; Badea, M.L.; Antohe, S. Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation on zinc doped hydroxyapatite in collagen matrix. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2015, 10, 681–691. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Patil, S.; Gao, Y.G.; Qian, A. The Bone Extracellular Matrix in Bone Formation and Regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, A.C.; Alves, G.G.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Sogayar, M.C.; Granjeiro, J.M. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins: Structure, biological function and therapeutic applications. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 561, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenda, M.; Kolmas, J. The Role of Zinc in Bone Tissue Health and Regeneration-a Review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 5640–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Yu, Y. Role of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 4230–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasnova, O.; Neganova, I. Assembling the Puzzle Pieces. Insights for in Vitro Bone Remodeling. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2023, 19, 1635–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; You, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zou, W. Mechanical regulation of bone remodeling. Bone Res. 2022, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Eligibility Criteria | Number of Excluded Entries (N) |

|---|---|

| Reviews articles, book chapters, and theses | 102 |

| Without zinc or a mixture of ions | 121 |

| Only physical-chemical tests | 43 |

| Only in vivo | 19 |

| Bacteriological | 12 |

| Other materials | 169 |

| Off-topic | 103 |

| Only abstract | 4 |

| Reference | Group I: Test Substance Identification [4] | Group II: Test System Characterization [3] | Group III: Study Design Description [7] | Group IV: Study Results Documentation [3] | Group V: Plausibility of Study Design and Data [2] | Total Score | Reliability Categorization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakhsheshi-Rad et al. [17] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 11 | Reliable with restrictions |

| Begam et al. [18] | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Bhattacharjee et al. [19] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Bhowmick et al. [20] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 16 | Reliable |

| Cao et al. [21] | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Chopra et al. [22] | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Cuozzo et al. [23] | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 16 | Reliable |

| Ding et al. [24] | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 14 | Reliable with restrictions |

| Dittler et al. [25] | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 16 | Reliable |

| Forte et al. [26] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Ghorbani et al. [27] | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 14 | Reliable with restrictions |

| He et al. [28] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Hidalgo-Robatto et al. [29] | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 16 | Reliable |

| Hou et al. [30] | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 15 | Reliable |

| Huang et al. [31] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Kazimierczak et al. [32] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Li et al. [33] | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 15 | Reliable |

| Li et al. [34] | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 15 | Reliable |

| Lima et al. [35] | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 15 | Reliable |

| Liu et al. [36] | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 16 | Reliable |

| Luo et al. [37] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 11 | Reliable with restrictions |

| Maleki-Ghaleh et al. [38] | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 16 | Reliable |

| Mavropoulos et al. [39] | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 15 | Reliable |

| Meng et al. [40] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| O’Sullivan et al. [41] | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 14 | Reliable with restrictions |

| Okada et al. [42] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Predoi et al. [43] | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Santos et al. [44] | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 15 | Reliable |

| Santos et al. [45] | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 15 | Reliable |

| Thian et al. [46] | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 16 | Reliable |

| Ullah et al. [47] | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Valarmathi and Sumathi [48] | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Wang et al. [49] | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 17 | Reliable |

| Wang et al. [50] | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 16 | Reliable |

| Webster et al. [51] | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 16 | Reliable |

| Webster et al. [52] | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | Reliable |

| Yang et al. [53] | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 13 | Reliable with restrictions |

| Zhang [54] | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 14 | Reliable with restrictions |

| Zhong and Ma [55] | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 15 | Reliable |

| Reference | Material | Theoretical/Real Amount of Zn2+ Added to the Biomaterial | Zn2+ Incorporation Method | Amount of Zn2+ Released into Media |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakhsheshi-Rad et al. [17] | Coating of titanium nanoparticle | Not indicated | Immersion in a solution of 100 ppm of ZnCl2 | 57 ppm |

| Begam et al. [18] | Blocks | 5%/2.9% | Precipitation of 5 weight % ZnO | Not indicated |

| Bhattacharjee et al. [19] | Coating of titanium disc | 0.10, 0.25, and 0.5 wt%/Not indicated | Mechanochemical synthesis | Not indicated |

| Bhowmick et al. [20] | Nanocomposite/CTS-PEG-HAP-ZnO 1 | 5%, 10%, and 15%/Not indicated | Nanoparticles of ZnO were prepared by Zn(OAc)2 (0.45 M) | Not indicated |

| Cao et al. [21] | Bilayer hydrogel scaffold | ZnHA 2–0.1%, 0.5%, and 1.0% (w/v)/Not indicated | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Chopra et al. [22] | Nanoparticle | ZnHA 2.76%/Not indicated | Hydrothermal synthesis | Not indicated |

| Cuozzo et al. [23] | Microspheres | ZnHA 0.5%/Not indicated | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Ding et al. [24] | Coating of titanium discs | ZnHA–Not indicated/1.33 wt% | Precipitation of 0.05 M Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Dittler et al. [25] | Coating of bioglass | ZnHA–Not indicated/10,800 ppm | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Forte et al. [26] | Disc | Not indicated | Precipitation 1.08 M of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Ghorbani et al. [27] | Scaffold/PCL-Ch-nZnHA 3 | 5%/Not indicated | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| He et al. [28] | Film/Titanium | Not indicated | Precipitation of 0.1 mol/L Zn(NO3)2 | F-ZCP 4 0.2 μg/mL - TiO2/D-ZCP 5 0.10 μg/mL -TiO2/S-ZCP 6-0.08 μg/ml |

| Hidalgo-Robatto et al. [29] | Coating of titanium disc | ZnHA 2.5%/0.15% ZnHA 5.0%/0.99% ZnHA 7.5%/0.88% ZnHA 10%/1.89% | Mixture of ZnO with commercial HA | Not indicated |

| Hou et al. [30] | Coating of titanium implants | ZnHA–2.5%/release | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Huang et al. [31] | Powder | 15%/9.21 | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | 120 mg/L |

| Kazimierczak et al. [32] | Chitosan-agarose-doped HA scaffold | ZnHA 1 mol/Not indicated | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Chit/Aga/HA-Zn–4.42 μg/mL |

| Li et al. [33] | Glass powders | CaO-P2O5-ZnO-Na2O 2 mol%/Not indicated | Precipitation of 2 mol% Zn(NO3)2 | 3.58–3.54 ppm |

| Li et al. [34] | Powder | ZnHA (1%, 2%, 4%, and 8%) | Precipitation different values of Zn(NO3)2 2 M | Not indicated |

| Lima et al. [35] | Granules | ZnHA 1%/0.1% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | 1 ppm |

| Liu et al. [36] | Coating of titanium discs | Not indicated | VIPF-APS 7 Technique | Not indicated |

| Luo et al. [37] | Coating of titanium discs (Tixos–commercial titanium) | ZnHA 10%/Not indicated ZnHA 20%/Not indicated ZnHA 30%/Not indicated | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Maleki-Ghaleh et al. [38] | Nanoparticles | Not indicated | Mechanochemical | Not indicated |

| Mavropoulos et al. [39] | Disc | ZnHA–Not indicated/2.3% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Meng et al. [40] | Coating of titanium discs | 1% and 2%/Not indicated | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | 1% ZnHA/TiO–3.8 ppm, 2% ZnHA/TiO–5.5 ppm |

| O’Sullivan et al. [41] | Coating of titanium discs | Not indicated/9 ppm | Deposition of ZnHA powder | 0.45 ppm |

| Okada et al. [42] | Powder | ZnHA 5%/4.3% ZnHA 10%/9.2% ZnHA 15%/14.7% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Predoi et al. [43] | Powder | Not indicated/0.06% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Santos et al. [44] | Composite (Nanoparticle and Collagen) | Not indicated | Precipitation of 0.158 mol% Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Santos et al. [45] | Composite (Nanoparticle and Collagen) | Not indicated | Precipitation of 1.0 mol% Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Thian et al. [46] | Disc | ZnHA 1.5%/1.6% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Ullah et al. [47] | Disc | ZnHA 5%/2.66% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | ZnHA1 5%–1 mg/L |

| Valarmathi and Sumathi [48] | Nanocomposite/Zn-HAP/SF/MC8 | (Ca + Zn) 1 mM | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Wang et al. [49] | Nanoparticle | PAA-CaP/Zn9 5%/Real concentration–Not indicated | Precipitation of ZnCL2 (0.0000061 M) | Not indicated |

| Wang et al. [50] | Rods/Nanoparticles | Z1-0.0056 mM/1.2 × 10−4 μg/cm2 Z2-0.056 mM/0.06 μg/cm2 Z3-0.56 mM/0.195 μg/cm2 | Precipitation of ZnCL2 (0.0056 mM, 0.056 mM, 0.56 mM) | Not indicated |

| Webster et al. [51] | Disc | 5%/0.7% | Precipitation of Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Webster et al. [52] | Borosilicate glass coverslips/covered ZnHA | 2%/Not indicated | Precipitation (Concentration and solution source of Zn not indicated) | Not indicated |

| Yang et al. [53] | Plates | 10%/1.04% | Precipitation of 10% Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Zhang [54] | Coating of titanium discs | ZnHA/TiO− (0.0025 M), ZnHA/TiO2− (0.005 M), and ZnHA/TiO3− (0.01 M)/Not indicated | Dipping the films in 0.0025 M, 0.005 M, and 0.01 M Zn(NO3)2 | ZnHA/TiO− 0.058 ZnHA/TiO2− 0.06, and ZnHA/TiO3− 0.066 |

| Zhong and Ma [55] | Nanoparticle coating of Titanium sheets | ZnHA 2%/2.0% ZnHA 5%/2.4% | Precipitation of 0.1 mol/L Zn(NO3)2 | Not indicated |

| Reference | Elemental Analysis | Composition | Crystallinity | Degradation/ Dissolution | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakhsheshi-Rad et al. [17] | EDX 1 | - | XRD 2 | ICP-OES 3/SBF 4 | EDX—incorporation of Zn in ZnHA, ratio (Zn + Ca)/P = 1.54; XRD—characteristic parameters of HA; there was a reduction of the ZnHA crystallite. SBF—the samples suffered corrosion, releasing Zn (57 ppm) |

| Begam et al. [18] | AAS 5 | FTIR 6 | XRD | - | AAS—detected the presence of Zn in the HA; XRD—crystallinity reduced after incorporation of Zn; FTIR—intensity of the phosphate group decreased after Zn incorporation |

| Bhattacharjee et al. [19] | - | - | XRD | - | XRD—confirms the conditions for the formation and retention of ZnHA characteristics |

| Bhowmick et al. [20] | - | FTIR | XRD | - | FTIR—identified the presence of ZnO NPs associated with HA; XRD—confirmed the presence of peaks corresponding to ZnO. Thus, there was no change in the crystalline network of the HA |

| Cao et al. [21] | EDX | - | XRD | - | XRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks and reduction in intensity indicate the incorporation of Zn; EDX—identified the presence of Zn in the sample |

| Chopra et al. [22] | EDX | FTIR | XRD | ICP-MS 7 | XRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks. Changes in the XRD peaks, in the morphology of the FESEM 8 crystals, and the Raman bands indicate the replacement of Ca by Zn in the HA structure; ICP—revealed the release of Zn within 60 days |

| Cuozzo et al. [23] | EDX | - | XRD | - | XRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks; EDX-identified peaks characteristic of the presence of Zn |

| Ding et al. [24] | EDX | FTIR | XRD | - | EDX —the Zn/P molar ratio of 0.053; XRD—Incorporation of Zn reduction of cell HA parameters. Peaks correspondents of HA; FTIR—HA characteristic bands, presence carbonate group, the sample was calcium deficient |

| Dittler et al. [25] | ICP-AES 9/XPS 10 | FTIR | XRD | ICP-AES/PBS 11 | TEM 12—confirmed the crystalline formation of the material; EDX and XPS—confirmed the presence of Zn in the material. Changes in the Ca/P and Ca/O ratio indicated the incorporation of Zn into the material; FTIR—characteristic Ca/P bands; ICP-AES—quantified the incorporation of Zn into Ca/P and the release of low doses of Zn in PBS solution |

| Forte et al. [26] | ICP-AES | Raman | XRD | - | XRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks without changes after the addition of PEI, without changes in the crystalline structure; ICP-AES—proved the presence of Zn2+ in the material structure; Raman—presented corresponding Ca/P groups |

| Ghorbani et al. [27] | FESEM/EDX | ATR-FTIR 13 | XRD | - | XRD—presence of specific hydroxyapatite peaks; ATR-FTIR—confirmed the presence of calcium phosphate in the nanocomposite; EDX—confirmed the presence of Zn in the material |

| He et al. [28] | - | - | XRD | ICP-MS/Tris-HCL | XRD—suggests low crystallinity of Zn-HA; ICP-MS—gradual release of Zn2+ |

| Hidalgo-Robatto et al. [29] | EDX | FTIR | XRD | - | EDX—reveals the presence of zinc; XPS9—quantified a Zn/Ca molecular ratio between 0.01 and 0.11; XRD—parameter characteristic of HA and Zn-doped HA decreases the crystal size; FTIR—spectra corresponded to HA |

| Hou et al. [30] | - | - | - | - | No description of the physical-chemical characterization |

| Huang et al. [31] | EDX/XRF 14/XPS | FTIR | XRD | ICP-AES/PBS | XRD and ATR-FTIR—confirmed characteristic Ca/P peaks and bands, and metal substitution did not interfere with the formation of nanocrystals; EDX—uniform distribution of Zn on the surface of the material; ICP-AES—confirms the gradual release of zinc at low doses |

| Kazimierczak et al. [32] | - | FTIR/PXRD | PXRD 15 | Spectrophotometer/alpha-MEM | PXRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks and presence of only one crystalline phase. Addition of Zn did not change the crystallinity of the material; FTIR—presence of characteristic Ca/P bands and reduction in the intensity of the OH- band suggests the replacement of Zn in the HA structure; ICP-AES—identified the presence of Zn after the production of scaffolds |

| Li et al. [33] | EDX | - | XRD | AAS/SBF | XRD—shows peak characteristics of HA, amorphous structure; AAS—gradual release of Zn in SBF solution. EDX- analyzed the new apatite formation; (Zn + Ca)/P = 1.55, sample deficient in Ca |

| Li et al. [34] | EDX | FTIR | XRD | - | EDX—revealed the presence of zinc and suggested incorporation in HA structure; XRD—Different concentrations of doped zinc represent a variation in crystallinity parameters; FTIR—zinc doping did not modify the internal structure |

| Lima et al. [35] | AAS | FTIR | XRD | AAS/DMEM 16 | AAS—revealed the incorporation of 0.1% of the Zn in HA; XRD—typical crystallinity of HA. No indicated Zn doped and possible modification; FTIR—indicated monophasic sample; AAS—after 24 h, 0.8 ppm of Zn was released in solution |

| Liu et al. [36] | FESEM/EDX | FTIR | XRD | - | XRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks; FTIR—identified the presence of characteristic Ca/P bands; EDX—identified the presence of Zn in the sample |

| Luo et al. [37] | - | - | SEM 17 | - | Crystal lattice contraction |

| Maleki-Ghaleh et al. [38] | XPS | ATR-FTIR | XRD | - | XRD and ATR-FTIR—confirmed characteristic Ca/P peaks and bands |

| Mavropoulos et al. [39] | XRF | ATR-FTIR | XRD | - | XRF—Zn-HA presented Zn in 2.3%; XRD—parameter compatible with HA. Zn-doped reduced the crystallite size; ATR-FTIR—shows HA characteristic groups and detects the adsorbed proteins |

| Meng et al. [40] | - | - | XRD | AAS/DMEM | XRD—presence of peaks related to Ca/P phosphate, indicative of zinc replacement in the material’s structure; AAS/DMEM—low doses of Zn were identified in the culture medium for cell exposure. In 28 days, the Zn concentration was reduced in the supernatant |

| O’Sullivan et al. [41] | EDX, XPS, and ICP-OES | - | - | ICP-OES/PBS | XPS, EDX, and ICP-OES—different quantified concentrations of zinc doped into HA. The variation corresponds to the different techniques; ICP-OES—Zn-HA released only 10% of the Zn doped into HA |

| Okada et al. [42] | ICP-AES | FTIR | XRD | - | XRD—indicated the presence of characteristic Ca/P peaks. Changes in peak intensity were related to incorporating Zn into the HA structure. The increase in Zn concentration altered the crystalline formation of the material; FTIR—identified characteristic Ca/P bands. Changes in the vibration of the OH- bands showed shortening with increasing Zn incorporation; ICP-AES—confirmed the presence of Zn in the samples with an incorporation efficiency of 85% relative to the expected concentration of metal incorporation |

| Predoi et al. [43] | - | FTIR | XRD | - | XRD—suggests low crystallinity and characteristic peaks; FTIR—showed specific bands of calcium phosphate; EDX—presence of zinc in samples |

| Santos et al. [44] | - | - | - | - | No description of physical-chemical characterization |

| Santos et al. [45] | - | - | - | - | No description of physical-chemical characterization |

| Thian et al. [46] | XRF, XPS | FTIR | SAED 18, XRD | - | SAED—polycrystalline-shaped crystals. Substitution of Zn in HA has been shown to reduce the size of HA crystals. There was no formation of new crystalline phases; FTIR—shows corresponding compounds of HA; XRF and XPS—show the incorporation of Zn; XRF—quantified Zn in 1.6 wt% |

| Ullah et al. [47] | ICP-AES | ATR-FTIR | XRD | ICP-AES/PBS | XRD—indicated the presence of characteristic Ca/P peaks, with changes in intensity following the incorporation of Zn. Latitude parameters (a) and (c) indicate the presence of Zn in the material structure and reduction in crystallinity; FTIR—showed characteristic Ha peaks after Zn incorporation; ICP-AES—revealed the incorporation and release of Zn from the material |

| Valarmathi and Sumathi [48] | EDX | FTIR | XRD | - | XRD—characteristic Ca/P peaks and changes in peak intensities reveal the variation in Zn incorporation into the material structure. Identified the reduction in crystallite size from peak analysis; FTIR—identified the characteristic Ca/P groups |

| Wang et al. [49] | ICP-AES and EDX | FTIR | XRD | - | XRD—crystalline structure evaluation, while not quantified. Characteristic peaks were similar to HA; FTIR—analysis of functional groups; EDX—confirmed the presence of Zn; ICP-AES—quantified Zn/Ca atomic ratio at 5.85% |

| Wang et al. [50] | XPS and ICP-AES | - | XRD | - | XPS confirmed the presence of Zn; ICP-AES quantified Zn. The addition of Zn decreases the crystal size. |

| Webster et al. [51] | EDX | - | XRD | - | EDX—incorporation of 0.7% form Zn; XRD—crystal reduction after incorporation of Zn |

| Webster et al. [52] | - | - | - | - | No indication of any results that prove Zn incorporation or structural changes |

| Yang et al. [53] | ICP-AES | - | - | - | ICP-AES—indicated the ratio of Zn/(Ca + Zn), molar ratio 1.04% |

| Zhang [54] | - | - | XRD | Plasma spectrometer/Tris-buffer solution (0.05 M) | With the increase of Zn incorporation, the HA phase was reduced. Zinc can be gradually released |

| Zhong and Ma [55] | EDX | FTIR | TEM, XRD | - | The presence of Zn in the SF-2% ZnHA and SF-5% ZnHA samples was 2% and 2.4%, respectively. The crystallinity parameters were not detailed. With the addition of Zn, Zn-HA agglomerates increased slightly after exposure to SBF, and bone-like apatite formed. |

| Reference | Cell Type | Biological in Vitro Tests | Genes/Proteins Assessed | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakhsheshi-Rad et al. [17] | MG-63 (human osteosarcoma cell line) | MTT 1 and FM 2 (DAPI 3) | - | Cells showed high affinity and cytocompatibility |

| Begam et al. [18] | MG-63 | Alamar Blue, MTT, CLSM 4, SEM | - | Increased viability and adhesion on ZnHA 1250; increased cell growth compared to the control |

| Bhattacharjee et al. [19] | hFOB (human fetal osteoblast cells) | MTT and FESEM | - | No significant variation in viability compared to the control. Cells presented a healthy morphology due to the presence of phyllodes |

| Bhowmick et al. [20] | Erythrocytes and MG-63 | Hemolytic assay, MTT | - | Cytocompatibility with blood; increased cell viability; no significant increase in proliferation |

| Cao et al. [21] | hADMSCs (human adipose mesenchymal stem cells) | FM (Live/dead), CCK-8 (WST-8) 5 | ALP 6, OPN 7, and RUNX2 8 | High biocompatibility, proliferation, and cell adhesion on the scaffold with ZnHA; Greater mineralization and expression of osteogenic markers in the SBH2 material (0.5% ZnHA) |

| Chopra et al. [22] | L929 (mouse fibroblast cell line); MSCs (mesenchymal stem cells); HUVECs (Human umbilical vein endothelial cells) | MTT, FM, and SEM | MSCs: ALP, COL1 9, BMP2 10, OCN 11, OPN, and mineralization; HUVECs: cell migration, capillary formation, and gene expression (FGF2 12, VEGFA 13, and PDGF 14) | High biocompatibility with G3HapZn in all cell types; MSCs—increased expression of genes associated with bone formation: ALP (7 d); COL1 (7 and 14 d); RUNX2 (14 d and 21 d); BMP2 (14 d); OCN (7 d, 14 d and 21 d). Increased mineralization at 7 d and 14 d; HUVECs—increased angiogenesis, cell migration, and gene expression: FGF2, VEGFA, and PDGF in the presence of G3HapZn |

| Cuozzo et al. [23] | MC3T3-E1 (mouse preosteoblasts cell line) | PrestoBlue | - | No significant difference in cell viability |

| Ding et al. [24] | MC3T3-E1 | MTT and SEM | - | Typical cell morphology, with filipodia to anchor cells/increase cell viability |

| Dittler et al. [25] | MG-63 | WST8, BrdU 15, and SEM | - | No significant variation in cell viability compared to the control and low rate of cell adhesion; the association of metals Mg and Zn (Mg-Zn-HA-BG) showed a significant increase in all parameters, indicating synergy between the metals |

| Forte et al. [26] | MG-63 and 2T-110 (human osteoclast precursor cell line) | WST-1 16, MF | ALP, COL1, OPG 17, RANKL 18, TRAP 19 | ZnHa showed low cell recovery capacity after exposure to H2O2; ZnHA did not present significant variation in the quantification of the biomarkers evaluated |

| Ghorbani et al. [27] | hADMSCs | SEM and MTT | - | Cell adhesion; Zn concentration was not toxic; proliferation decrease |

| He et al. [28] | MC3T3-E1 | Alamar Blue and SEM | ALP, OCN, Col-1, Runx-2 | Morphology showed filopodia; increased viability; increased APL activity, and OCN secretion/TiO2/S-ZCP showed better performance in all evaluated cytokines |

| Hidalgo-Robatto et al. [29] | MC3T3-E1 | MTT, SEM, and CLSM (F-actin) | ALP | Adhesion and proliferation similar to control, good viability, and similar ALP activity between samples |

| Hou et al. [30] | HEPM (human embryonic palatal mesenchymal) | - | COL1A1 (COL1), TNFRSF11B (OPG), SPP1 (OPN) | Significant increase in the expression of COL1A1 (COL1) at 3 d and TNFRSF11B (OPG) at 7 d and 11 d |

| Huang et al. [31] | MSCs, OBs (osteoblasts), MC3T3-E1, 143b, MG-63, and UMR-106 (mouse osteosarcoma epithelial-like cell line) | Alamar Blue, CCK-8, FM | ALP, COL1, OCN, RUNX2, OPN | Extract biocompatibility and no changes in cell proliferation (5 d reduction of proliferation); high cell adhesion and spreading; low ALP activity compared to the control, but greater deposition of Ca nodules; osteogenic factors with lower expression compared to the Se/Sr/Zn-HA material |

| Kazimierczak et al. [32] | MC3T3-E1, BMDSCs (bone marrow-derived stem cells), and hADSCs | MTT, CLSM | COL1, ALP, and OCN | Chit/aga/HA-Zn—showed biocompatibility high cell spread with the extract (Zn 4.42 μg/mL); in contact with the scaffold, it showed low cell adhesion; no significant increase in COL1, ALP, and OCN rates |

| Li et al. [33] | MC3T3-E1 | SEM | - | Morphology typical, with filopodia and lamellipodia; increased proliferation, compared to the control, but decreased compared to the other samples |

| Li et al. [34] | MC3T3-E1 | CCK-8 | - | Decreased cell viability with high Zn concentration, but increased proliferation in Zn-HA 1%; morphology similar to the control in Zn-HA 1% |

| Lima et al. [35] | Balb/3T3 Clone A3 (mouse embryonic fibroblasts), primary human OBs, and human monocytes | XTT 20, NR 21, CVDE 22, apoptosis assay, and SEM | - | High cell viability and integrity membrane; no significant apoptosis; no difference in cell adhesion |

| Liu et al. [36] | hFOBs | MTT | ALP | More significant proliferation in the Zn-Hap-Ti group at 3 d. The group with the association of Zn, Sr, and Mg ions (ZnSrMg-Hap-Ti) showed more significant proliferation and ALP activity |

| Luo et al. [37] | MG-63 | FM (DAPI), CCK-8 (WST-8) and Total protein quantification | ALP, RUNX2, Osterix, OCN, COL1, and BMP2 | Increased proliferation, cell adhesion, and total protein quantification in ZnHA 20%. Osteogenic factors were increased by ZnHA 20%. |

| Maleki-Ghaleh et al. [38] | MSCs | MTT | ALP | Significant increase in cell proliferation and ALP activity in the presence of Zn-doped samples |

| Mavropoulos et al. [39] | MC3T3-E1 | XTT, NR, CVDE, SEM, FM | - | No significant difference in cell viability; morphology similar to the control and high adhesion; increased cell spreading and actin fibers formation |

| Meng et al. [40] | BALB/cBMSC (BMSCs isolated from healthy BALB/c mice cell line, osteoblasts) and Raw264.7 (murine macrophage from blood, osteoclasts precursors) | FM, MTT, LDH 23 | ALP, COL1, TRAP5, OCN, IL-1 24, TNF-α 25, PTH 26, RANKL | Osteoblasts—increase in viability, proliferation, and expression of ALP/COL1 and OCN in the presence of 1% and 2% ZnHA. Osteoclasts—significant increase in RANKL and TRAP5b at 21 d (co-culture), with stabilization at 28 d. Lower expression of IL-1 and TNF-α with no significant variation |

| O’Sullivan et al. [41] | MG-63 | MTT | - | Cytocompatibility and increase in proliferation |

| Okada et al. [42] | MC3T3-E1 | WST-8 | - | Significant increase in cell proliferation after exposure to 0.1 mg/mL of Zn(15)-Hap |

| Predoi et al. [43] | hFOB 1.19 | FM and MTT | - | High biocompatibility; Morphology of the cells showed no changes in their structure, and the presence of lamellipodia and filopodia was observed |

| Santos et al. [44] | MC3T3-E1 | MTT | ALP | No significant difference compared to the control |

| Santos et al. [45] | hOB | MTT | - | Cytocompatibility is similar to the control |

| Thian et al. [46] | ADMSCs | Alamar Blue, CLSM, SEM | COL1, OCN | Increased cell viability/similar to the control/showed evidence of biomineralization similar to the control/OCN expression increase in ZnHA |

| Ullah et al. [47] | MC3T3-E1 | CCK-8, FM, SEM | - | Less proliferation and adhesion were observed compared to the control group, with increased ALP activity. When co-substituted with Mg, it showed an increase in all analyzed parameters, indicating synergy between the metals |

| Valarmathi and Sumathi [48] | MG-63 | MTT | - | High biocompatibility of the optimized material (SM10 [Zn1.0]) at a concentration of 25 μg/mL. However, the concentration did not show significant variation compared to the control |

| Wang et al. [49] | rADSC (rat adipose-derived stem cells) | Alamar Blue, SEM, ARS 27 | ALP | Cell viability similar to the control; favorable to adhesion and proliferation; increased mineral deposition, significantly after ten days |

| Wang et al. [50] | NIH3T3 and MC3T3-E1 | CCK-8 (WST-8), MF, Bradford test | ALP | Fibroblasts: cell density increase; osteoblasts: increased DNA content and total proteins; cellular response was higher with the higher concentrations of Zn and increased significantly after three weeks |

| Webster et al. [51] | Human Osteoblasts (hOBs) | FM, BCA 28 Assay, Calcium assay | ALP | No difference in adhesion; increased mineral deposition; decreased APL expression as compared to all samples |

| Webster et al. [52] | MC3T3-E1 | Coomassie Brilliant Blue | - | Increased cell adhesion |

| Yang et al. [53] | MC3T3-E1 | Total protein quantification | ALP and OCN | Increased cell proliferation; increased ALP activity and OCN production (14 d) |

| Zhang [54] | MG-63 | MTT, SEM, and MF | - | increase cellular proliferation; characteristic morphology of differentiated cells with filopodia and grasped the surface; better adhesion |

| Zhong and Ma [55] | MC3T3-E1 | CCK-8 (WST-8), MF and SEM | ALP | Increased cell proliferation and ALP activity; ZnHA facilitated adhesion and proliferation, but adhesion is similar in all samples |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dornelas, J.; Dornelas, G.; Rossi, A.; Piattelli, A.; Di Pietro, N.; Romasco, T.; Mourão, C.F.; Alves, G.G. The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite and Its Influence on the Cellular Response to Biomaterials: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb15070178

Dornelas J, Dornelas G, Rossi A, Piattelli A, Di Pietro N, Romasco T, Mourão CF, Alves GG. The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite and Its Influence on the Cellular Response to Biomaterials: A Systematic Review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2024; 15(7):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb15070178

Chicago/Turabian StyleDornelas, Jessica, Giselle Dornelas, Alexandre Rossi, Adriano Piattelli, Natalia Di Pietro, Tea Romasco, Carlos Fernando Mourão, and Gutemberg Gomes Alves. 2024. "The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite and Its Influence on the Cellular Response to Biomaterials: A Systematic Review" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 15, no. 7: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb15070178

APA StyleDornelas, J., Dornelas, G., Rossi, A., Piattelli, A., Di Pietro, N., Romasco, T., Mourão, C. F., & Alves, G. G. (2024). The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite and Its Influence on the Cellular Response to Biomaterials: A Systematic Review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 15(7), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb15070178