Taking a Closer Look: The Relationship between Pre-School Domain General Cognition and School Mathematics Achievement When Controlling for Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Influence of Domain-General Abilities and Domain-Specific Knowledge on Mathematics Achievement Depending on Developmental Changes and Age

1.2. The Influence of Domain-General Abilities and Domain-Specific Knowledge Depending on the Different Specific Mathematics Achievements

1.3. Predictive Links between Working Memory and Mathematical Processing

1.4. Research Questions

- Do the domain-general and domain-specific achievements differ according to the pre-school intellectual abilities?

- Is there a difference in mathematical achievement between different intellectual ability groups in 2nd grade?

- Which pre-school abilities predict mathematical achievement in 2nd grade within each group?

- How do the different domain-general and domain-specific variables at pre-school predict mathematics at 2nd grade within each group?

2. Design, Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Tasks

2.4.1. Numerical and Mathematical Skills (t1 and t2)

2.4.2. Mathematical Abilities (t3)

2.4.3. Visuospatial Sketchpad

2.4.4. Phonological Loop

2.4.5. Central Executive

2.4.6. General Intelligence

2.4.7. Visual Attention

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlational Analyses

3.2. Comparison of Performance between Intellectual Ability Groups

- (1)

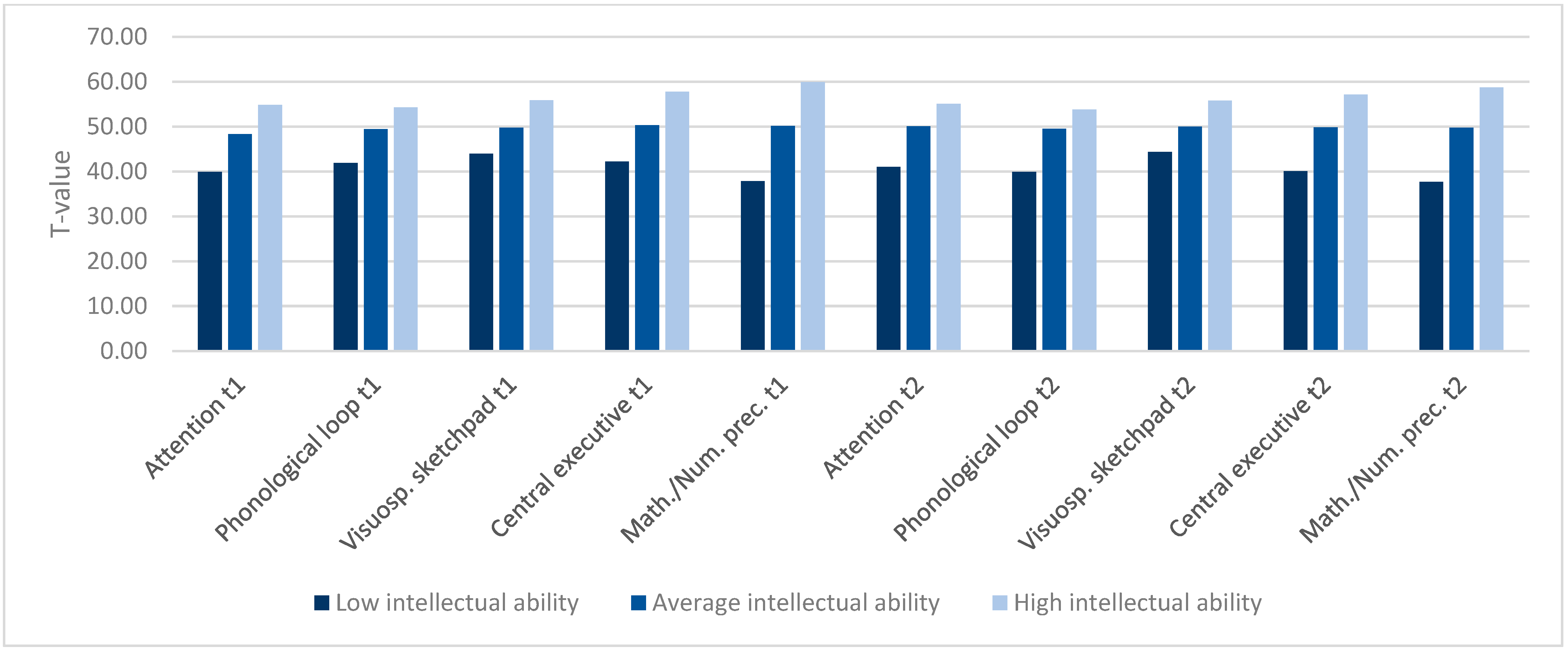

- There was a high main effect of group on mathematical/numerical precursor skills (domain-specific) at t1 and t2 (see Figure 1). Post-hoc tests (Hochberg) revealed significant differences (p < 0.001) between the three intellectual ability groups at t1 and t2. Children with low intellectual ability showed lower scores on mathematical/numerical precursor skills than children of average intellectual ability, who in turn scored lower than children of the high intellectual ability group. Furthermore, we found medium to high effect sizes for all domain-general skills at t1 and t2. Post-hoc tests (Hochberg and Games-Howell respectively) revealed the lowest achievement scores in all domain-general skills for children of the low intellectual ability group, followed by children of the average intellectual ability group. The highest scores in all domain-general skills were achieved by children of the high intellectual ability group.

- (2)

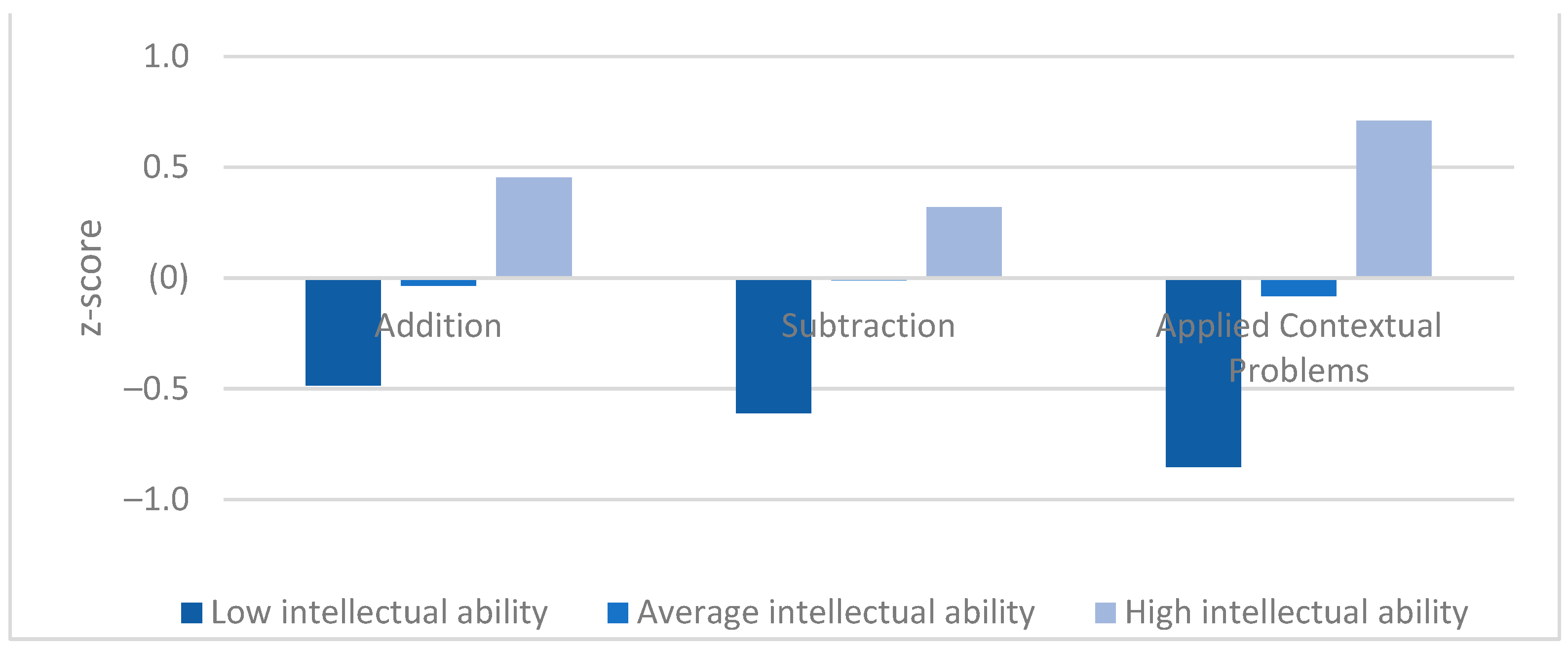

- There were low (addition and subtraction) to medium effects (applied contextual problems) on the mathematical achievements in 2nd grade (see Figure 2). Post-hoc tests (Games-Howell) revealed that children of the low intellectual ability group scored lower on three mathematical tasks than children of the average intellectual ability group, who in turn scored lower than children of the high intellectual ability group. The differences between the three intellectual ability groups in addition (p < .001), subtraction (p < .01) and applied contextual problems (p < .001) were significant.

- (3)

- A look at Figure 2 revealed that the three mathematical tasks seem to be differentially demanding for the three intellectual ability groups. Children of the low intellectual ability group showed the lowest achievement in applied contextual problems. This performance was significantly lower than that in written addition (t(67) = 6.159, p < .001) and in written subtraction (t(67) = 2.588, p = .012). No difference was found between children’s performance in written subtraction and addition (t(67) = 1.190, p = .238). In contrast, children of the high intellectual ability group showed the highest performance in applied contextual problems. This performance was significantly higher than that in written subtraction (t(122) = −3.547, p < .001) or written addition (t(122) = −2.534, p = .013). Again, no difference was found between written subtraction and addition (t(122) = 1.280, p = .203). Regarding the performance of children in the average intellectual ability group, the lowest performance was found in applied contextual problems. This performance was marginally significantly lower than their performance in written subtraction (t(707) = 7.873, p = .062) and slightly but not significantly lower than their performance in written addition (t(707) = 1.386, p = .166). Again, we could not find differences in the achievement between written addition and subtraction (t(707) = −0.609, p = .542).

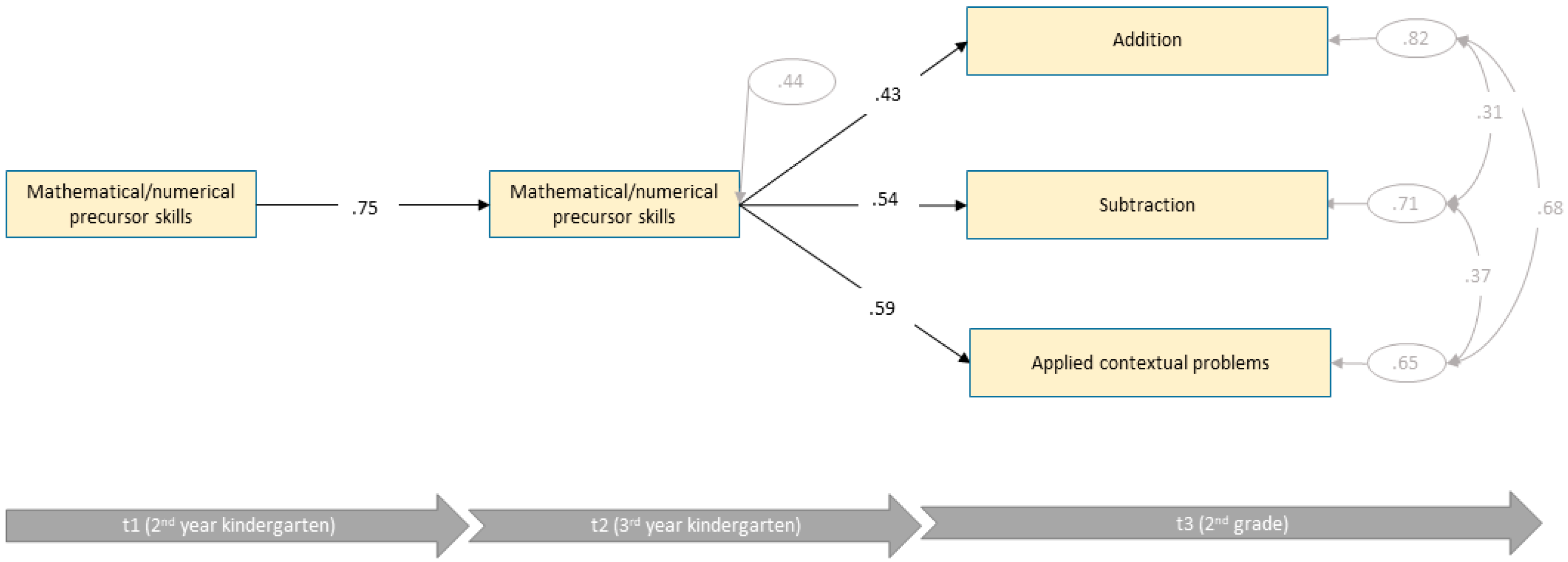

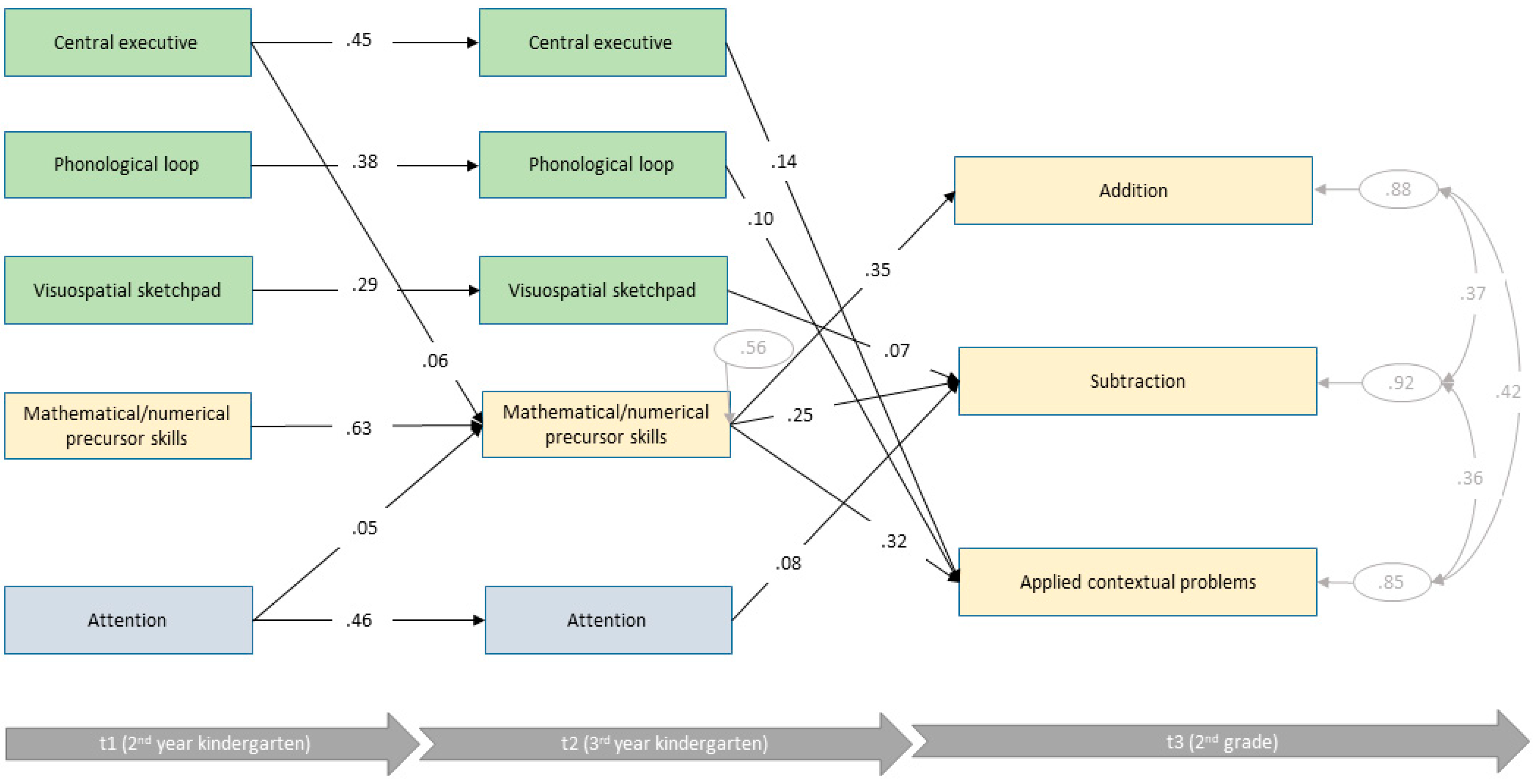

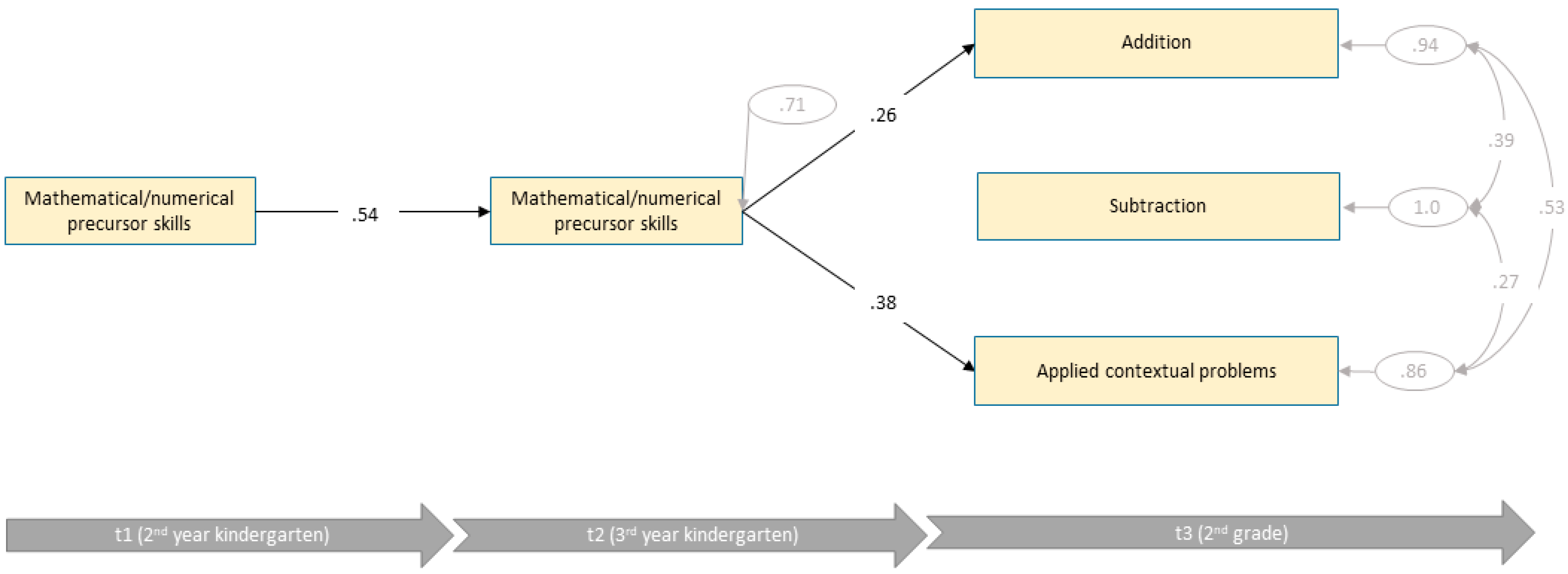

3.3. Path Analyses

3.3.1. Low Intellectual Ability Group

3.3.2. Average Intellectual Ability Group

3.3.3. High Intellectual Ability Group

3.3.4. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Children’s Domain-General and Domain-Specific Achievement Differs according to Their Intellectual Ability Group

4.2. The Relevance of Domain-General Abilities to Predict School Mathematics Changes according to Children’s Intellectual Ability

4.3. Different Mathematical Tasks Require Different Domain-General Resources

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, Phillip L., and Patrick C. Kyllonen. 1991. Trainee characteristics. In Training for Performance: Principles of Applied Human Learning. Edited by John E. Morrison. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 193–22. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Katie, David Giofrè, Steve Higgins, and John Adams. 2020. Working memory predictors of mathematics across the middle primary school years. British Journal of Educational Psychology 90: 848–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashcraft, Mark H. 1992. Cognitive arithmetic: A review of data and theory. Cognition 44: 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunio, Pirjo, and Markku Niemivirta. 2010. Predicting children’s mathematical performance in grade one by early numeracy. Learning and Individual Differences 20: 427–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, Alan D. 1986. Working Memory. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, Alan D. 2002. Is working memory still working? European Psychologist 7: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, Alan D. 2012. Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, Alan D., and Graham Hitch. 1974. Working Memory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation. New York: Academic Press, vol. 8, pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, John R., Patricia H. Miller, and Jack A. Naglieri. 2011. Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample. Learning and Individual Differences 21: 327–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulheller, Stephan, and Hartmut Häcker. 2002. Coloured Progressive Matrices (CPM). Deutsche Bearbeitung und Übersetzung nach J. C. Raven. Frankfurt: Pearson Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, Rebecca, Kimberly A. Espy, and Sandra A. Wiebe. 2008. Short-term memory, working memory, and executive functioning in preschoolers: Longitudinal predictors of mathematical achievement at age 7 years. Developmental Neuropsychology 33: 205–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, Lucia, Debbie Minden, Shirley X. Chen, Russel J. Schachar, and Abel Ickowicz. 2008. Mathematical Learning Disorder in School-Age Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 53: 392–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, John B. 1993. Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-Analytic Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Edward H., and Drew H. Bailey. 2021. Dual-Task Studies of Working Memory and Arithmetic Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 47: 220–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, Andrew R. A., Christopher Jarrold, Michael Kane, Akira Miyake, and John N. Towse. 2008. Variation in Working Memory: An Introduction. In Variation in Working Memory. Edited by Andrew R. A. Conway, Christopher Jarrold and Michael J. Kane. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, Nicola. 2005. Working Memory Capacity. In Essays in Cognitive Psychology. London: Tayler and Francis Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, Nicola. 2010. The Magical Mystery Four: How Is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why? Current Directions in Psychological Science 19: 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smedt, Bert, Lieven Verschaffel, and Pol Ghesquière. 2009. The predictive value of numerical magnitude comparison for individual differences in mathematics achievement. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 103: 469–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, Craig K. 2001. A Primer on Maximum Likelihood Algorithms Available for Use With Missing Data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 8: 128–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, Randall W. 2010. Role of Working-Memory Capacity in Cognitive Control. Current Anthropology 51 Suppl. S1: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, Günter, and Anne Wyschkon. 2016. BUEVA-III: Basisdiagnostik Umschriebener Entwicklungsstörungen im Vorschulalter—Version 3. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, Günter, Anne Wyschkon, and Katja Ballaschk. 2008. Basisdiagnostik Umschriebener Entwicklungsstörungen im Grundschulalter (BUEGA). Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Emilio, and John J. McArdle. 2004. An experimental analysis of dynamic hypotheses about cognitive abilities and achievement from childhood to early adulthood. Developmental Psychology 40: 935–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friso-van den Bos, Ilona, Sanne H. G. van der Ven, Evelyn H. Kroesbergen, and Johannes E. H. van Luit. 2013. Working memory and mathematics in primary school children: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 10: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, Annemarie, Antje Ehlert, and Lars Balzer. 2013. Development of mathematical concepts as the basis for an elaborated mathematical understanding. South African Journal of Childhood Education 3: 38–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, Annemarie, Antje Ehlert, and D. Detlev Leutner. 2018. Arithmetische Konzepte aus kognitiv-entwicklungspsychologischer Sicht. Journal für Mathematik-Didaktik 39: 7–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Lynn S., David C. Geary, Donald L. Compton, Douglas Fuchs, Carol L. Hamlett, Pamela M. Seethaler, Joan D. Bryant, and Christopher Schatschneider. 2010. Do different types of school mathematics development depend on different constellations of numerical versus general cognitive abilities? Developmental Psychology 46: 1731–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Lynn S., David C. Geary, Douglas Fuchs, Donald L. Compton, and Carol L. Hamlett. 2016. Pathways to third-grade calculation versus word-reading competence: Are they more alike or different? Child Development 87: 558–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallit, Finja, Anne Wyschkon, Nadine Poltz, Svenja Moraske, Karin Kucian, Michael von Aster, and Günter Esser. 2018. Henne oder Ei: Reziprozität mathematischer Vorläufer und Vorhersage des Rechnens. Lernen und Lernstörungen 7: 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Susan E., Claire Tiffany, Josie Briscoe, and Annabel Thorn. 2005. The ALSPAC team Developmental consequences of poor phonological short-term memory function in childhood: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46: 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, David C. 2011. Cognitive predictors of individual differences in achievement growth in mathematics: A five year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology 47: 1539–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, David C., Alan Nicholas, Yaoran Li, and Jianguo Sun. 2017. Developmental Change in the Influence of Domain-General Abilities and Domain-Specific Knowledge on Mathematics Achievement: An Eight-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Educational Psychology 47: 1539–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiser, Christian. 2011. Datenanalyse mit Mplus: Eine Anwendungsorientierte Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Goecke, Benjamin, Florian Schmitz, and Oliver Wilhelm. 2021. Binding Costs in Processing Efficiency as Determinants of Cognitive Ability. Journal of Intelligence 9: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, Hannelore. 2001. Sprachentwicklungstest für drei- bis Fünfjährige Kinder (SETK 3-5). Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric, and Johan O. Undheim. 1992. Stability and change in broad and narrow factors of intelligence from ages 12 to 15 years. Journal of Educational Psychology 84: 141–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbo, Ineke, and André Vandierendonck. 2007. The development of strategy use in elementary school children: Working memory and individual differences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 96: 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Michael J., David Z. Hambrick, and Andrew R. A. Conway. 2005. Working Memory Capacity and Fluid Intelligence Are Strongly Related Constructs: Comment on Ackerman, Beier, and Boyle 2005. Psychological Bulletin 131: 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, Kristin, Susann Liehm, and Wolfgang Schneider. 2004. DEMAT 2+: Deutscher Mathematiktest für Zweite Klassen. Göttingen: Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Kucian, Karin, Michael von Aster, Thomas Loenneker, Thomas Dietrich, and Ernst Martin. 2008. Development of neural networks for number processing: A fMRI study in children and adults. Developmental Neuropsychology 33: 447–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyllonen, Patrick C., and Raymond E. Christal. 1990. Reasoning ability is (little more than) working-memory capacity?! Intelligence 14: 389–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kerry, and Rebecca Bull. 2016. Developmental changes in working memory, updating, and math achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology 108: 869–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yaoran, and David C. Geary. 2013. Developmental gains in visuospatial memory predict gains in mathematics achievement. PLoS ONE 8: e70160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Zhanhong, Peiqi Dong, Yanlin Zhou, Shanshan Feng, and Qiong Zhang. 2022. Whether Verbal and Visuospatial Working Memory Play Different Roles in Pupil’s Mathematical Abilities. British Journal of Educational Psychology 92: e12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, Ronald L., Terry Tomazic, Melvin D. Levine, and Pasquale J. Accardo. 2001. Attentional Function as Measured by a Continuous Performance Task in Children with Dyscalculia. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 22: 287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehler, Claudia, and Kirsten Schuchardt. 2009. Working memory functioning in children with learning disabilities: Does intelligence make a difference? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 53: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, Irene C., Sara Caviola, David Giofrè, and Dénes Szűcs. 2018. The underlying structure of visuospatial working memory in children with mathematical learning disability. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 36: 220–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manger, Terje, and Ole-Johan Eikeland. 1998. The effect of mathematics selfconcept on girls’ and boys’ mathematical achievement. School Psychology International 19: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, Michèle M. M., and Sara T. Kover. 2007. A longitudinal assessment of executive functioning skills and their association with math performance. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence 13: 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Bruce, Rebecca Bull, and Colin Gray. 2003. The effects of phonological and visual spatial interference on children’s arithmetical performance. Educational and Child Psychology 20: 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Jeremy, and Mark Shevlin. 2001. Applying Regression and Correlation: A Guide for Students and Researchers. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, Brenda. 1971. Interhemispheric differences in the localization of psychological processes in man. British Medical Bulletin 27: 272–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Akira, Naomi P. Friedman, Michael J. Emerson, Alexander H. Witzki, Amy Howerter, and Tor D. Wager. 2000. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology 41: 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Kou, Reinhard Pekrun, Stephanie Lichtenfeld, and Rudolf vom Hofe. 2012. Predicting Long-Term Growth in Students’ Mathematics Achievement: The Unique Contributions of Motivation and Cognitive Strategies. Child Development 87: 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthèn, Linda K., and Bengt O. Muthèn. 2013. Mplus Version 7.11 [Software]. Los Angelos: Muthèn and Muthèn. [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer, Klaus, Ralf Schulze, Oliver Wilhelm, and Heinz-Martin Süß. 2005. Working Memory and Intelligence–Their Correlation and Their Relation: Comment on Ackerman, Beier, and Boyle 2005. Psychological Bulletin 131: 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passolunghi, Maria C. 2011. Cognitive and emotional factors in children with mathematical learning disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 58: 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passolunghi, Maria C., and Cesare Cornoldi. 2008. Working memory failures in children with arithmetical difficulties. Child Neuropsychology 14: 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penner, Andrew M. 2003. International gender X item difficulty interactions in mathematics and science achievement tests. Journal of Educational Psychology 95: 650–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, Susan, and Susan E. Gathercole. 2001. Working Memory Test Battery for Children (WMTB-C). London: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Poltz, Nadine, Sabine Quandte, Juliane Kohn, Karin Kucian, Anne Wyschkon, Michael von Aster, and Günter Esser. 2022. Does It Count? Pre-School Childrens’ Spontaneous Focusing on Numerosity and Their Development of Arithmetical Skills at School. Brain Sciences 12: 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghubar, Kimberly P., Marcia A. Barnes, and Steven A. Hecht. 2010. Working memory and mathematics: A review of developmental, individual difference, and cognitive approaches. Learning and Individual Differences 20: 110–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, Rajadurai, and Genapathi Hema. 2018. Assessing General Intelligence in Influencing Performance of Mathematics. Journal on Educational Psychology 12: 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Carmen, and Jeffrey Bisanz. 2005. Representation and working memory in early arithmetic. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 91: 137–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricken, Gabi, Annemarie Fritz, Karl D. Schuck, and Ulrich Preuss. 2007. HAWIVA-III, Hannover-Wechsler-Intelligenztest für das Vorschulalter-III. Göttingen: Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Roebers, Claudia M., and Christof Zoelch. 2005. Erfassung und Struktur des phonologischen und visuellräumlichen Arbeitsgedächtnisses bei 4-jährigen Kindern. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie 37: 113–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saß, Steffani, Nele Kampa, and Olaf Köller. 2017. The interplay of g and mathematical abilities in large-scale assessments across grades. Intelligence 63: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Corinne, Christof Zoelch, and Claudia M. Roebers. 2008. Das Arbeitsgedächtnis von 4- bis 5-jährigen Kindern: Theoretische und empirische Analyse seiner Funktionen. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie 40: 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Wolfgang. 2008. The development of metacognitive knowledge in children and adolescents: Major trends and implications for education. Mind, Brain, and Education 2: 114–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Wolfgang, Joachim Körkel, and Franz Weinert. 1989. Domain-specific knowledge and memory performance. Journal of Educational Psychology 81: 306–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, Ruth S., Judy Auerbach, and Varda Gross-Tsur. 1995. Developmental dyscalculia behavioral and attentional aspects: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 36: 1261–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, Robert S. 1988. Strategy choice procedures and the development of multiplication skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 117: 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, Robert S., Greg J. Duncan, Pamela E. Davis-Kean, Kathryn Duckworth, Amy Claessens, Mimi Engel, Maria I. Susperreguy, and Meichu Chen. 2012. Early predictors of high school mathematic achievement. Psychological Science 23: 691–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanlou, Mojtaba, Silvia Pixner, and Hans-Christoph Nuerk. 2015. Contribution of working memory in multiplication fact network in children may shift from verbal to visuo-spatial: A longitudinal investigation. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szűcs, Denes, Amy Devine, Fruzsina Soltesz, Alison Nobes, and Florence Gabriel. 2013. Developmental dyscalculia is related to visuo-spatial memory and inhibition impairment. Cortex 49: 2674–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, Sylke W. M., Sanne H. G. Van der Ven, Evelyn H. Kroesbergen, and Johannes E. H. Van Luit. 2011. Executive functions as predictors of math learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities 44: 521–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, Sylke W. M., Evelyn H. Kroesbergen, and Johannes E. H. Van Luit. 2016. Visual working memory and number sense: Testing the double deficit hypothesis in mathematics. British Journal of Educational Psychology 86: 429–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Weijer-Bergsma, Eva, Evelyn H. Kroesbergen, and Johannes E. H. Van Luit. 2015. Verbal and visual-spatial working memory and mathematical ability in different domains throughout primary school. Memory and Cognition 43: 367–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Aster, Michael G., and Ruth S. Shalev. 2007. Number development and developmental dyscalculia. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 49: 868–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Aster, Michael G., Michael W. Bzufka, and Ralf Horn. 2009. ZAREKI-K: Neuropsychologische Testbatterie für Zahlenverarbeitung und Rechnen bei Kindern–Kindergartenversion. Frankfurt: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Li, Chen Cao, Xinlin Zhou, and Chunxia Qi. 2022. Spatial Abilities Associated with Open Math Problem Solving. Applied Cognitive Psychology 36: 306–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, Tyler W., Greg J. Duncan, Robert S. Siegler, and Pamela E. Davis-Kean. 2014. What’s past is prologue: Relations between early mathematics knowledge and high school achievement. Educational Researcher 43: 352–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, Franz E. 2001. Schulleistungen—Leistungen der Schule oder der Schüler? In Leistungsmessungen in Schulen. Beltz: Weinheim, S. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Oliver, Andrea Hildebrandt, and Klaus Oberauer. 2013. What is working memory capacity, and how can we measure it? Frontiers in Psychology 4: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 (df), p | RMSEA (90% CI: Lower/Upper) | CFI | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-factor | 214.45 (62), <0.001 | 0.04 (0.04/0.05) | 0.96 | 16,617 | 16,836 |

| 2-factor | 663.76 (64), <0.001 | 0.08 (0.08/0.09) | 0.85 | 17,062 | 17,270 |

| 1-factor | 826.94 (65), <0.001 | 0.09 (0.09/0.10) | 0.81 | 17,223 | 17,426 |

| Model | χ2 (df), p | RMSEA (90% CI: Lower/Upper) | CFI | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | 3-factor | 2003.73 (662), <0.001 | 0.03 (0.03/0.03) | 0.89 | 48,635 | 49,280 |

| 1-factor | 4983.99 (665), <0.001 | 0.06 (0.06/0.06) | 0.60 | 51,609 | 52,238 | |

| t2 | 3-factor | 1288.93 (662); <0.001 | 0.02 (0.02/0.03) | 0.92 | 50,313 | 50,946 |

| 1-factor | 3717.60 (665), <0.001 | 0.05 (0.05/0.05) | 0.61 | 52,736 | 53,353 |

| n | M | SD | Range | Skewness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||||

| t1 | |||||

| Age (months) | 1868 | 62.98 | 4.35 | 49–81 | 0.42 |

| Intelligence | 1866 | 49.15 | 10.08 | 19–69 | −0.07 |

| Attention | 1856 | 48.19 | 9.13 | 20–60 | −0.56 |

| Phonological Loop | 1823 | 49.19 | 8.57 | 23–60 | −0.54 |

| Visuospatial sketchpad | 1821 | 49.75 | 9.88 | 21–81 | 0.05 |

| Central executive | 1809 | 50.05 | 9.74 | 28–81 | 0.17 |

| Mathem./numerical precursor skills | 1808 | 49.91 | 10.01 | 17–84 | 0.01 |

| t2 | |||||

| Age (months) | 1705 | 72.36 | 4.20 | 60–89 | 0.41 |

| Intelligence | 1704 | 50.70 | 9.74 | 15–69 | −0.25 |

| Attention | 1698 | 49.73 | 8.63 | 20–60 | −0.67 |

| Phonological Loop | 1651 | 49.15 | 8.71 | 19–60 | −0.69 |

| Visuospatial sketchpad | 1655 | 50.38 | 9.86 | 19–78 | −0.07 |

| Central executive | 1652 | 49.94 | 9.70 | 24–74 | −0.01 |

| Mathem./numerical precursor skills | 1647 | 49.87 | 10.03 | 18–80 | −0.05 |

| t3 | |||||

| Age (months) | 1348 | 94.79 | 4.08 | 79–111 | 0.35 |

| Addition | 1337 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.81–2.75 | 1.17 |

| Subtraction | 1337 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1.26–1.21 | −0.07 |

| Applied contextual problems | 1350 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1.22–2.11 | 0.38 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IQ | - | 0.40 (1696) | 0.39 (1649) | 0.24 (1653) | 0.42 (1650) | 0.50 (1645) |

| 2 | Attention | 0.46 (1855) | - | 0.21 (1648) | 0.30 (1652) | 0.29 (1650) | 0.37 (1646) |

| 3 | Phonological loop | 0.40 (1822) | 0.21 (1814) | - | 0.22 (1651) | 0.40 (1648) | 0.39 (1642) |

| 4 | Visuospatial sketchpad | 0.31 (1821) | 0.31 (1814) | 0.24 (1819) | - | 0.28 (1652) | 0.36 (1646) |

| 5 | Central executive | 0.41 (1809) | 0.29 (1803) | 0.35 (1807) | 0.31 (1808) | - | 0.43 (1644) |

| 6 | Math./Numeric. precursor skills | 0.57 (1807) | 0.42 (1802) | 0.40 (1806) | 0.43 (1807) | 0.43 (1800) | - |

| t2 | t3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

| t1 | 1 | IQ | 0.71 (1702) | 0.40 (1696) | 0.39 (1649) | 0.24 (1653) | 0.42 (1650) | 0.50 (1645) | 0.20 (1337) | 0.23 (1337) | 0.42 (1350) |

| 2 | Attention | 0.46 (1855) | 0.52 (1690) | 0.22 (1644) | 0.29 (1647) | 0.28 (1644) | 0.36 (1641) | 0.14 (1334) | 0.19 (1334) | 0.23 (1347) | |

| 3 | Phonological loop | 0.40 (1822) | 0.18 (1666) | 0.48 (1624) | 0.13 (1627) | 0.34 (1624) | 0.31 (1619) | 0.08 (1304) | 0.08 (1304) | 0.23 (1317) | |

| 4 | Visuospatial sketchpad | 0.31 (1821) | 0.30 (1664) | 0.24 (1819) | 0.34 (1624) | 0.29 (1621) | 0.35 (1618) | 0.20 (1305) | 0.13 (1305) | 0.24 (1318) | |

| 5 | Central executive | 0.41 (1809) | 0.24 (1657) | 0.17 (1621) | 0.22 (1616) | 0.53 (1614) | 0.36 (1611) | 0.14 (1297) | 0.16 (1297) | 0.26 (1310) | |

| 6 | Math./Numeric. precursor skills | 0.57 (1807) | 0.38 (1657) | 0.34 (1613) | 0.38 (1616) | 0.46 (1614) | 0.74 (1611) | 0.35 (1297) | 0.32 (1297) | 0.48 (1310) | |

| t3 | 7 | Addition | 0.24 (1274) | 0.15 (1271) | 0.15 (1239) | 0.15 (1241) | 0.21 (1240) | 0.37 (1237) | - | 0.45 (1337) | 0.52 (1337) |

| 8 | Subtraction | 0.24 (1274) | 0.20 (1271) | 0.15 (1239) | 0.20 (1241) | 0.20 (1240) | 0.32 (1237) | - | 0.43 (1337) | ||

| 9 | Applied contextual problems | 0.42 (1286) | 0.19 (1283) | 0.29 (1251) | 0.20 (1253) | 0.37 (1252) | 0.49 (1249) | - | |||

| Low Intellectual Ability | Average Intellectual Ability | High Intellectual Ability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F(df, df) | η2 | |

| t1 (n) | n = 135–148 | n = 910–923 | n = 135–138 | |||||

| Age (months) 1 | 64.62 | 5.06 | 62.91 | 4.19 | 62.15 | 4.04 | 10.84 (2, 236) * | .02 |

| Intelligence 1 | 32.59 | 4.68 | 49.29 | 5.28 | 65.40 | 3.47 | 2371.03 (2, 276) * | .72 |

| Attention 1 | 39.92 | 8.83 | 48.36 | 8.74 | 54.80 | 5.63 | 150.54 (2, 264) * | .16 |

| Phonological Loop 1 | 41.92 | 9.15 | 49.44 | 8.24 | 54.24 | 6.41 | 86.09 (2, 245) * | .12 |

| Visuospatial sketchpad | 43.93 | 9.43 | 49.76 | 9.47 | 55.87 | 9.93 | 54.54 (2, 1185) * | .08 |

| Central executive | 42.24 | 8.20 | 50.31 | 9.01 | 57.73 | 9.91 | 100.29 (2, 1185) * | .15 |

| Mathematical/numerical precursor skills | 37.87 | 8.19 | 50.14 | 8.36 | 59.88 | 8.30 | 237.61 (2, 1178) * | .29 |

| t2 (n) | n = 137–145 | n = 895–922 | n = 135–138 | |||||

| Age (months) 1 | 73.91 | 5.00 | 72.39 | 4.02 | 71.26 | 3.80 | 12.80 (2, 236) * | .02 |

| Intelligence 1 | 32.93 | 4.83 | 50.14 | 5.21 | 65.33 | 3.32 | 2319.51 (2, 276) * | .72 |

| Attention 1 | 40.99 | 8.93 | 50.03 | 8.02 | 55.11 | 5.96 | 123.79 (2, 252) * | .17 |

| Phonological Loop 1 | 39.87 | 9.53 | 49.48 | 8.05 | 53.78 | 6.74 | 97.71 (2, 234) * | .16 |

| Visuospatial sketchpad | 44.36 | 8.24 | 50.00 | 9.70 | 55.81 | 9.33 | 50.15 (2, 1169) * | .08 |

| Central executive | 40.07 | 8.14 | 49.86 | 8.95 | 57.16 | 8.71 | 131.44 (2, 1166) * | .18 |

| Mathematical/numerical precursor skills | 37.69 | 9.35 | 49.76 | 8.54 | 58.72 | 8.39 | 206.06 (2, 1164) * | .26 |

| t3 (n) | n = 68–69 | n = 708–711 | n = 123–127 | |||||

| Age (months) | 97.13 | 4.57 | 94.80 | 3.98 | 93.88 | 3.76 | 14.89 (2, 903)* | .03 |

| Addition 1 | −0.49 | 0.72 | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.45 | 1.17 | 23.71 (2, 147)* | .05 |

| Subtraction 1 | −0.61 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.94 | 22.18 (2, 145)* | .04 |

| Applied contextual problems 1 | −0.85 | 0.62 | −0.08 | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.97 | 94.31 (2, 162) * | .13 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ehlert, A.; Poltz, N.; Quandte, S.; Kohn, J.; Kucian, K.; Von Aster, M.; Esser, G. Taking a Closer Look: The Relationship between Pre-School Domain General Cognition and School Mathematics Achievement When Controlling for Intelligence. J. Intell. 2022, 10, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10030070

Ehlert A, Poltz N, Quandte S, Kohn J, Kucian K, Von Aster M, Esser G. Taking a Closer Look: The Relationship between Pre-School Domain General Cognition and School Mathematics Achievement When Controlling for Intelligence. Journal of Intelligence. 2022; 10(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleEhlert, Antje, Nadine Poltz, Sabine Quandte, Juliane Kohn, Karin Kucian, Michael Von Aster, and Günter Esser. 2022. "Taking a Closer Look: The Relationship between Pre-School Domain General Cognition and School Mathematics Achievement When Controlling for Intelligence" Journal of Intelligence 10, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10030070

APA StyleEhlert, A., Poltz, N., Quandte, S., Kohn, J., Kucian, K., Von Aster, M., & Esser, G. (2022). Taking a Closer Look: The Relationship between Pre-School Domain General Cognition and School Mathematics Achievement When Controlling for Intelligence. Journal of Intelligence, 10(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10030070