This section provides a comprehensive empirical evaluation of the proposed BTC quantization method under PTQ without retraining. Experiments were carried out on convolutional networks (ResNet, ShuffleNet, MobileNet, and RepVGG) and fully connected models (MLP), using three benchmark datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and tabular classification data. BTC is compared directly against the full-precision FP32 baseline and standard 8-bit uniform quantization. The evaluation focuses on classification accuracy, quantization RMSE, average bit usage per weight, and training-stability behavior. Across all models and datasets, BTC demonstrates very stable behavior, achieving 4–7.7 average bits per weight with accuracy degradation typically below 2–3%, clearly outperforming uniform 8-bit quantization in compression efficiency. These results clearly demonstrate that BTC provides a substantially better compression–accuracy trade-off than uniform quantization, particularly for architectures with highly structured convolutional filters or heavy channel bottlenecks. To further validate the robustness and scalability of the proposed approach, additional experiments are conducted on large-scale ImageNet models, where BTC is compared against a calibrated percentile-based uniform PTQ baseline. This comparison highlights BTC’s ability to achieve substantial bitwidth reduction relative to calibration-aware 8-bit quantization while maintaining competitive accuracy, thereby confirming the practical relevance of BTC beyond small-scale benchmarks.

3.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were performed using pretrained models from the Chenyaofo repository [

39], covering the following:

ResNet20, ResNet32, ResNet44, ResNet56.

ShuffleNetV2 (0.5×, 1.0×).

MobileNetV2_x0.5.

RepVGG-A0 (additional verification).

MLP architecture.

All experiments were implemented in PyTorch 2.0 using the torchvision module for dataset loading and preprocessing. Training and evaluation were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU and an Intel Core i9 processor. All experiments rely exclusively on standard PyTorch inference operators. No custom CUDA or Triton kernels were implemented, and no kernel-level modifications were introduced for BTC decoding or mixed-precision execution. It is important to emphasize that BTC quantizes only the network weights (convolution kernels and FC-layer weights). All backward-pass quantities, including gradients and optimizer states, remain in full precision. Thus, BTC is evaluated purely as a post-training weight compression method, without affecting the optimization dynamics. Throughout all experiments, BTC is applied exclusively to network weights, while gradients and optimizer states remain in full precision. We emphasize that BTC primarily targets model storage reduction and memory efficiency. While inference time decoding is lightweight and static, actual runtime speedups depend on hardware support for mixed precision or block-wise weight decoding and are therefore not claimed as a universal property of the proposed method.

BTC quantization was applied to all convolutional and fully connected layers. Block sizes were increased adaptively based on two stopping criteria: (1) RMSE threshold—stop when RMSE exceeds , and (2) Accuracy threshold—stop when accuracy decreases by more than . For every quantized model we computed accuracy, RMSE, bit usage, and histogram shifts in quantized weights. Although the main focus of this work is the accuracy/compression trade-off, we briefly note that BTC is applied as an offline re-encoding of already trained weights. The transform and bitplane coding steps are executed once per layer, whereas inference requires only lightweight blockwise decoding operations with linear complexity in the block size. It is important to note that BTC does not introduce dynamic precision switching during inference. Bitwidth selection is performed offline during PTQ, resulting in a static mixed-precision weight representation. Consequently, BTC avoids warp divergence and conditional execution overhead on standard GPU and NPU architectures. In all experiments, we did not observe any noticeable slowdown relative to uniform quantization on a modern GPU, suggesting that the proposed method is compatible with practical deployment.

Although BTC applies a single global variance threshold across the entire network, the resulting mode selection exhibits a clear layer-dependent structure. To analyze this behavior, we record the proportion of blocks within each layer that are assigned to the high-precision (8-bit) mode. Across all evaluated architectures, early convolutional layers and final classification layers consistently exhibit a higher fraction of 8-bit blocks. These layers are known to be more sensitive to quantization noise, as early layers directly process raw input features, while final layers strongly influence class decision boundaries. In contrast, intermediate convolutional or bottleneck layers tend to activate the low-precision (4-bit) mode more frequently, reflecting smoother weight distributions and higher tolerance to quantization error. Although we do not report per-layer numerical breakdowns for all architectures, we observed consistent order of magnitude trends when averaging the BTC mode activations across models and datasets. In particular, early convolutional layers typically allocate on the order of 55– of blocks to the high-precision (8-bit) mode, while intermediate layers predominantly operate in the low-precision regime, with approximately 70– of blocks encoded at 4 bits. Final classification layers exhibit a more balanced behavior, with roughly 45– of blocks activating the 8-bit mode. These values should be interpreted as representative averages rather than exact layer-wise statistics, and are reported to illustrate the consistent qualitative behavior of BTC across different network architectures. This emergent behavior confirms that BTC implicitly captures layer-wise sensitivity without requiring explicit per-layer tuning, calibration data, or heuristic bit assignment rules. Instead, the block-level variance criterion naturally allocates higher precision to structurally critical layers while aggressively compressing statistically redundant regions.

3.2. Obtained Results

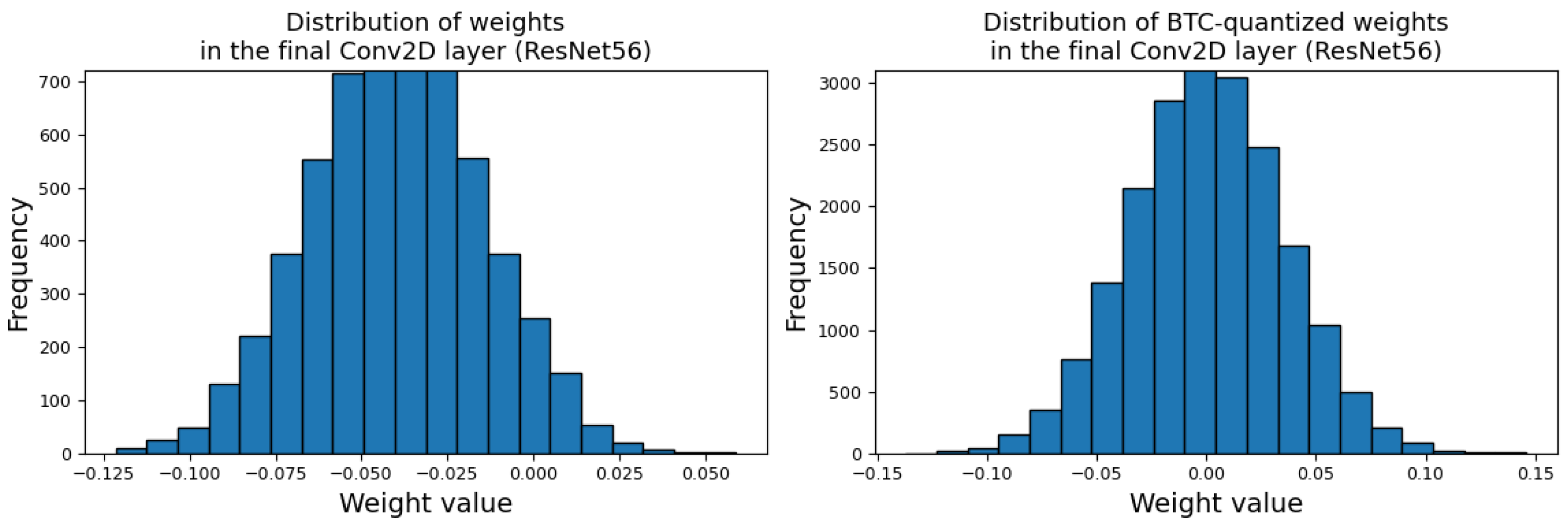

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of convolutional weights before and after applying BTC (compared with uniform quantization). BTC preserves the smooth, unimodal, approximately Gaussian-shaped structure of the weights, while uniform quantization produces plateauing and hard discretization artifacts, explaining why BTC induces significantly lower distortion under the same bit budget.

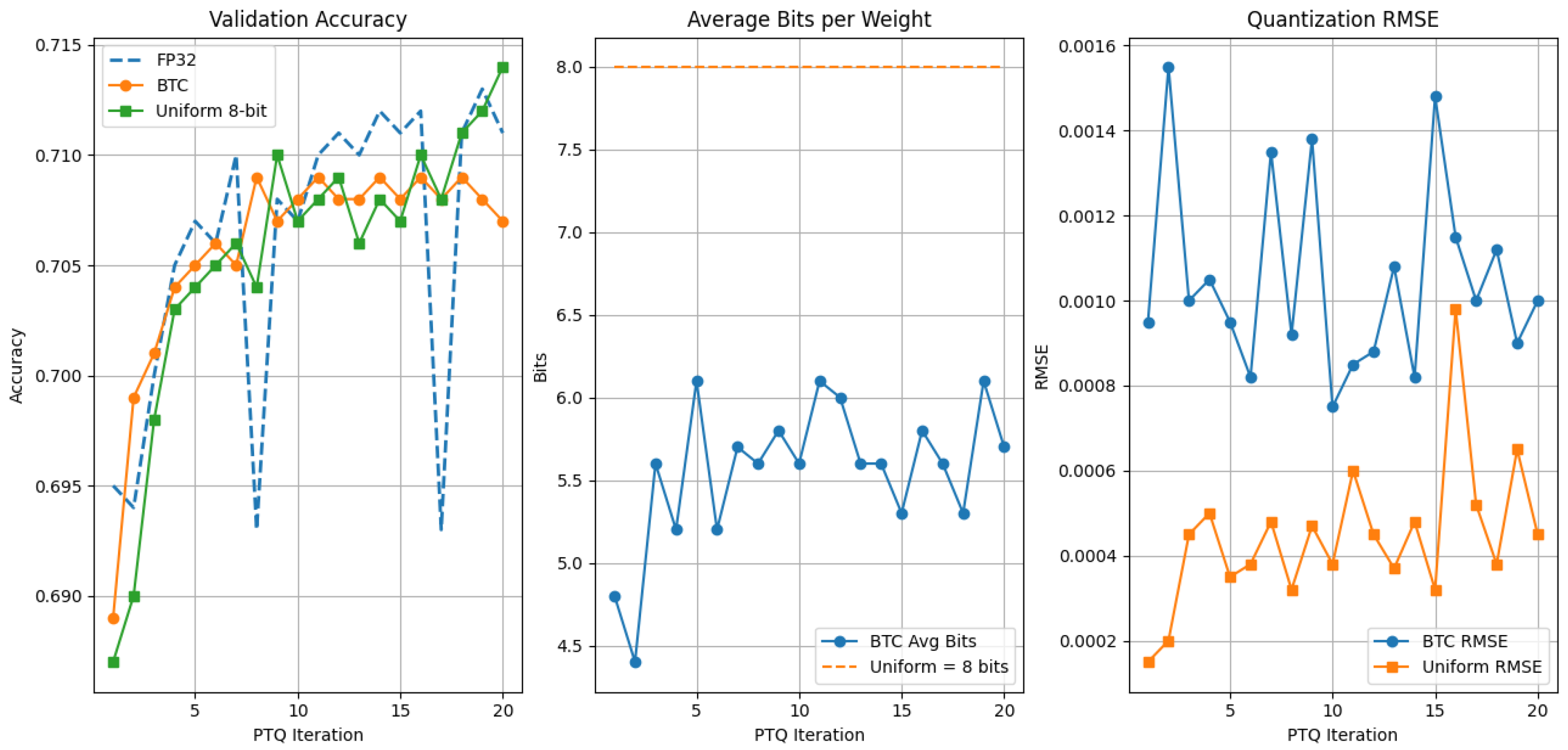

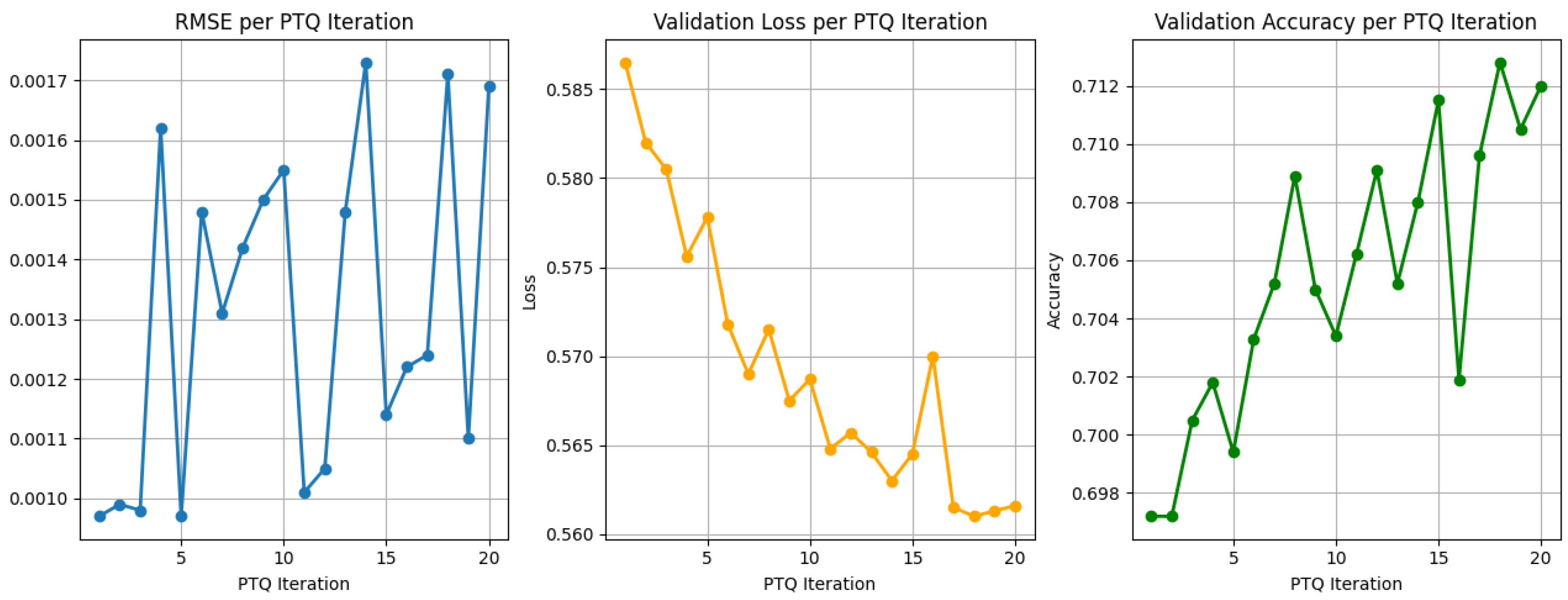

It is important to clarify that the proposed BTC method is strictly a PTQ technique. All NNs used in this study are fully pretrained prior to quantization and no backpropagation, gradient updates, or parameter optimization is performed after BTC is applied. The sequential evaluation plots shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 do not represent training epochs. Instead, each iteration corresponds to a successive quantization step, where BTC is applied with progressively adjusted block sizes or thresholds, followed by a forward-only inference pass to evaluate accuracy and loss. These plots are included solely to illustrate the stability of model performance under repeated quantization refinement, not to suggest any form of retraining or fine-tuning.

Figure 2 illustrates the PTQ behavior of the proposed BTC method and uniform quantization for the MLP model. Each point corresponds to an independent PTQ configuration applied to a fixed pretrained network, rather than a training epoch. BTC exhibits consistently lower quantization noise and dynamically adapts its effective precision (typically in the range of 4.5–6.3 bits), in contrast to the fixed 8-bit uniform baseline.

Figure 3 reports the post-training evaluation loss and accuracy obtained after each PTQ iteration for the MLP architecture. The results demonstrate that BTC preserves inference stability under post-training weight quantization, yielding smooth post-training loss behavior and stable accuracy across successive quantization configurations without retraining, backpropagation, or weight updates.

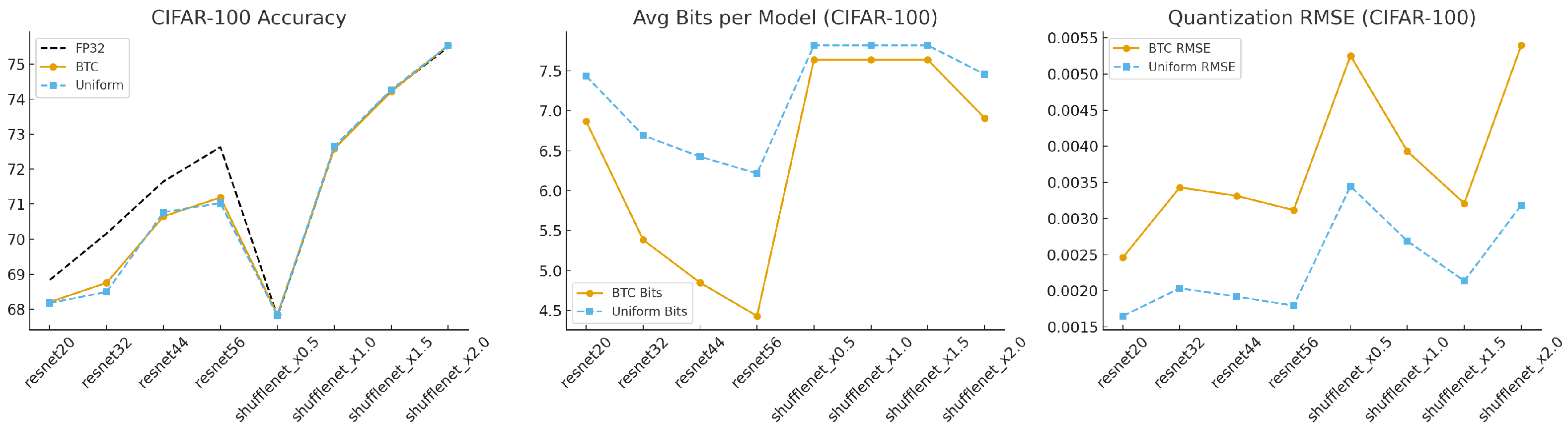

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 further visualize the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 results.

The results show that BTC generalizes well across architectures with fundamentally different microstructures (ResNet, ShuffleNet, MobileNet, and RepVGG). Finally,

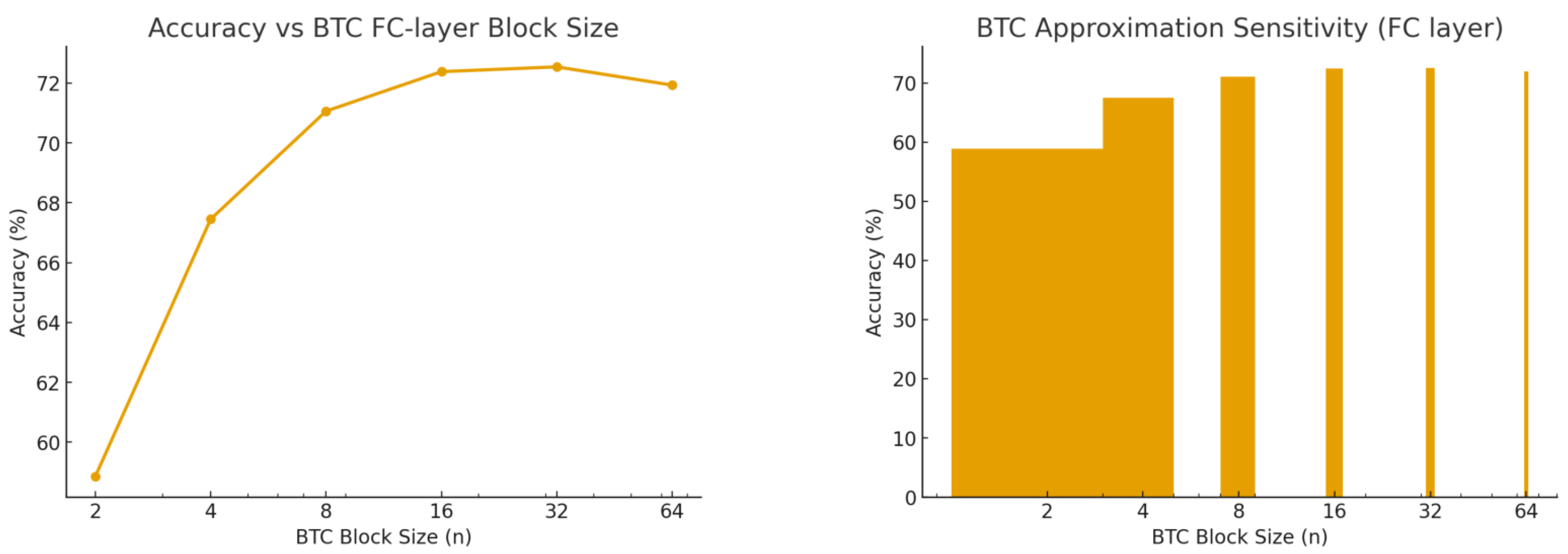

Figure 6 analyzes BTC behavior as the block size increases (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64). Accuracy saturates rapidly for block sizes

, indicating that BTC is robust to block-size choice and can flexibly trade computational cost against compression efficiency. Beyond these individual observations, the collection of figures provides a coherent picture of BTC’s operational advantages. The histogram analysis (

Figure 1) reveals why BTC maintains low distortion: the transform-domain representation mitigates quantization granularity and preserves inter-weight correlations.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show that BTC preserves FP32-level behavior across successive post-training quantization steps for the MLP model. The CIFAR-10/100 summaries (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) confirm that these benefits persist across both shallow and deep convolutional networks, as well as across datasets of varying difficulty. Lastly, the block-size study (

Figure 6) highlights the practical flexibility of BTC: moderate block sizes already achieve near-optimal accuracy, implying that practitioners can tune BTC to balance compression ratio, runtime overhead, and hardware constraints without sacrificing predictive performance. Collectively, the figures establish BTC as a stable, generalizable, and computationally efficient quantization scheme.

The CIFAR-10 results in

Table 2 show that BTC consistently preserves accuracy across all evaluated architectures while achieving substantial bit-rate reductions. For the four ResNet variants, BTC remains within 0.4–0.6 pp of the FP32 baseline, while reducing average bit usage from a fixed 8 bits (uniform) to just 4.1–5.0 bits, representing a 35–50% compression gain. Importantly, BTC achieves even lower RMSE values than uniform quantization in most cases, confirming that the block-transform re-encoding preserves the underlying weight structure more faithfully. ShuffleNetV2 and MobileNetV2 models follow the same trend: accuracy differences between BTC and FP32 are negligible (≤0.6 pp), with BTC achieving competitive RMSE values and consistently better compression than uniform quantization. The CIFAR-100 benchmark in

Table 3 further highlights the robustness of BTC on a more challenging dataset. Although CIFAR-100 typically exhibits higher sensitivity to quantization, BTC maintains accuracy within 1.0–1.5 pp of FP32 across all ResNet depths, while again using only 4.4–6.9 bits on average. Uniform quantization, in contrast, requires 6.2–7.8 bits with similar or slightly worse accuracy. Models with highly compressed architectures, such as ShuffleNetV2 and MobileNetV2, also show minimal degradation (≤0.4 pp), demonstrating that BTC adapts well even to networks with narrow channels and depthwise separable convolutions. RMSE values remain low and stable across all experiments, typically in the 0.002–0.005 range. The aggregated cross-architecture summary in

Table 4 reinforces the general applicability of BTC. ResNet models exhibit the strongest compression–accuracy trade-off, achieving 4.1–5.0 bits with only 0.8–1.3% accuracy loss. ShuffleNetV2, which is known to be highly sensitive to quantization, maintains nearly identical accuracy to FP32 while relying on 7.2–7.8 bits per weight. MobileNetV2, a depthwise separable architecture, shows somewhat higher sensitivity but still maintains competitive performance at 5.8–6.0 bits. Fully connected MLPs achieve the lowest RMSE values, and accuracy drops below 0.5%, confirming that BTC adapts extremely well to both convolutional and non-convolutional weight distributions. In addition to the payload bits used to represent quantized weights, BTC stores a small per-block header. For each block of length

B, we store

and a mode flag indicating whether the block is encoded at 4-bit or 8-bit precision. Therefore, the effective bit-width per weight is

, where

is the average payload precision (reported in our tables) and

. In our implementation,

are stored in

FP16 (32 bits total) and

bit; hence,

bits per block. For example, the overhead equals

bits/weight for

, and drops to

bits/weight for

. For clarity, the BTC bit values reported in the CIFAR tables represent the average payload precision

. The corresponding effective bit-width, including the block header, is given by

, and can be readily computed for any chosen block size. As shown in

Table 5, the relative header overhead decreases rapidly with increasing block size and becomes negligible for practical configurations (

). Importantly, the header cost is independent of the selected bit-width and does not materially affect the overall compression efficiency reported in the experimental results. Overall, these results demonstrate strong generalization across model families and datasets, validating the stability and effectiveness of the BTC quantization scheme.

To further strengthen the validity of the proposed approach and address the limitations of comparisons based solely on naïve uniform quantization, we additionally evaluated BTC against a calibrated percentile-based uniform post-PTQ baseline on ImageNet (ILSVRC) [

40]. Percentile-based clipping represents a widely adopted and practically relevant PTQ strategy, as it mitigates the impact of outliers and typically provides significantly better accuracy preservation than simple min-max uniform quantization.

Table 6 reports the Top-1 validation accuracy obtained on ImageNet for three representative pretrained ResNet architectures. The percentile-based uniform PTQ baseline achieves accuracy nearly identical to the FP32 reference, confirming the effectiveness of calibrated clipping when a fixed 8-bit representation is employed. In contrast, BTC operates in a substantially more aggressive compression regime, reducing the average precision to approximately 4.1–4.6 bits per weight. Despite this significant reduction in bit-width, BTC maintains accuracy within 0.4–0.8 percentage points of the FP32 baseline across all evaluated models. The observed accuracy gap between BTC and percentile PTQ reflects the expected trade-off between compression ratio and accuracy, rather than instability or optimization artifacts.

These results highlight a key advantage of BTC: while calibrated uniform PTQ excels in accuracy preservation at a fixed 8-bit precision, BTC achieves a markedly better compression/accuracy balance by adapting the effective bitwidth to the local statistics of weight blocks. In practical deployment scenarios where memory footprint, bandwidth, or hardware constraints are critical, BTC offers a compelling alternative by halving the average bit precision with only a marginal accuracy loss. Importantly, BTC achieves this trade-off without calibration datasets, gradient-based reconstruction, or layer-wise optimization, relying instead on a single-pass, offline block transform. This positions BTC as a lightweight and scalable PTQ method that complements reconstruction-based approaches, rather than competing with them directly, and underscores its suitability for efficient inference on resource-constrained platforms.

Overall, BTC demonstrates excellent generalization across both CNN and MLP architectures, offering strong compression efficiency with minimal loss in predictive performance. Across more than twenty architectures and both CIFAR datasets, the results consistently show that BTC achieves between 4 and 7.7 bits per weight on average, compared to the fixed 8-bit uniform baseline, while maintaining accuracy degradation below 3%. The quantization error remains tightly controlled, with RMSE values typically below 0.003, and histogram as well as stability analyses confirm that the block-based transform preserves the structural distribution of weights far better than uniform quantization. Additional ImageNet experiments with a calibrated percentile-based uniform PTQ baseline further indicate that BTC operates in a more aggressive compression regime, achieving substantially lower average bitwidths at the cost of a modest and predictable accuracy reduction. It should be emphasized that the primary benefit of BTC lies in reducing the model storage footprint rather than guaranteeing universal inference acceleration. While BTC substantially lowers the average bitwidth of weights and memory bandwidth requirements, actual inference speedups depend on hardware support for mixed-precision or block-wise decoding. BTC operates as an offline weight-only compression scheme: all block-level metadata are resolved during the encoding stage and do not introduce any conditional logic or header decoding during the inference forward pass. It is important to emphasize that BTC is intentionally designed to operate in a more aggressive compression regime, prioritizing substantial reductions in average bit-width over strict accuracy preservation. In comparison with calibrated PTQ baselines on ImageNet, BTC trades a modest and predictable accuracy loss for a significantly smaller model footprint, making it particularly suitable for scenarios where calibration data, reconstruction, or optimization are undesirable or infeasible. BTC therefore offers a competitive and well-controlled compression–accuracy trade-off, particularly in scenarios where calibration-free, low-complexity post-training quantization is desired and strict 8-bit accuracy preservation is not the primary objective. These results demonstrate that BTC quantization is a flexible and practical method for substantially reducing model size and computational footprint while maintaining robust predictive performance.