Service Mode Switching for Autonomous Robots and Small Intelligent Vehicles Using Pedestrian Personality Categorization and Flow Series Fluctuation

Abstract

1. Introduction

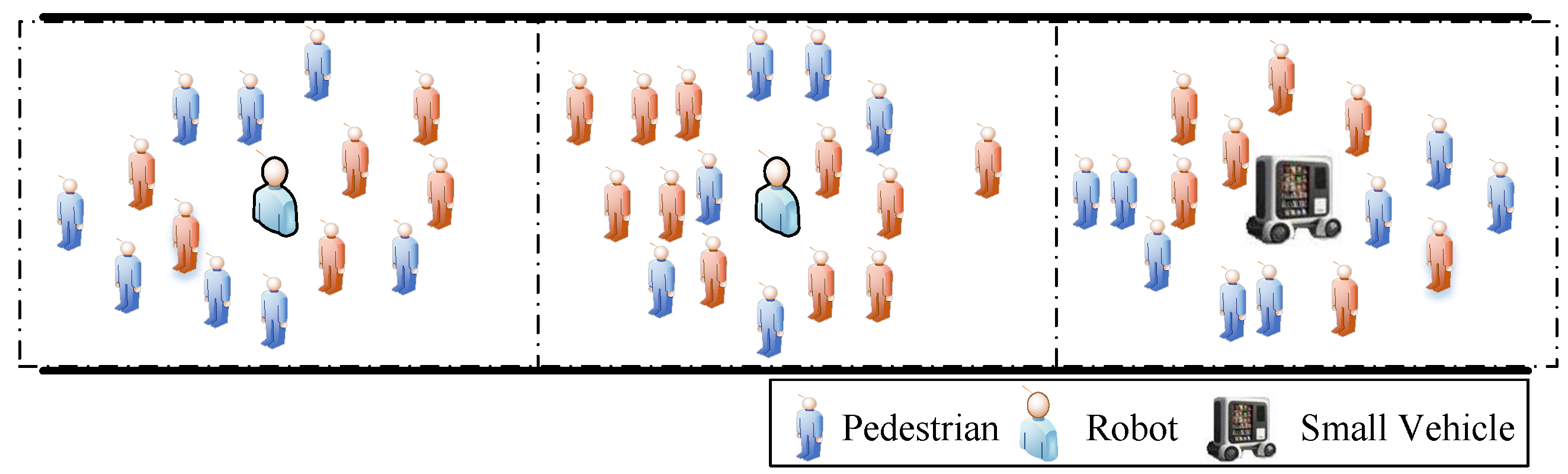

2. Scenario Description and Data Collection

3. Modification of SFM Based on Pedestrian Classification

3.1. Traditional SFM

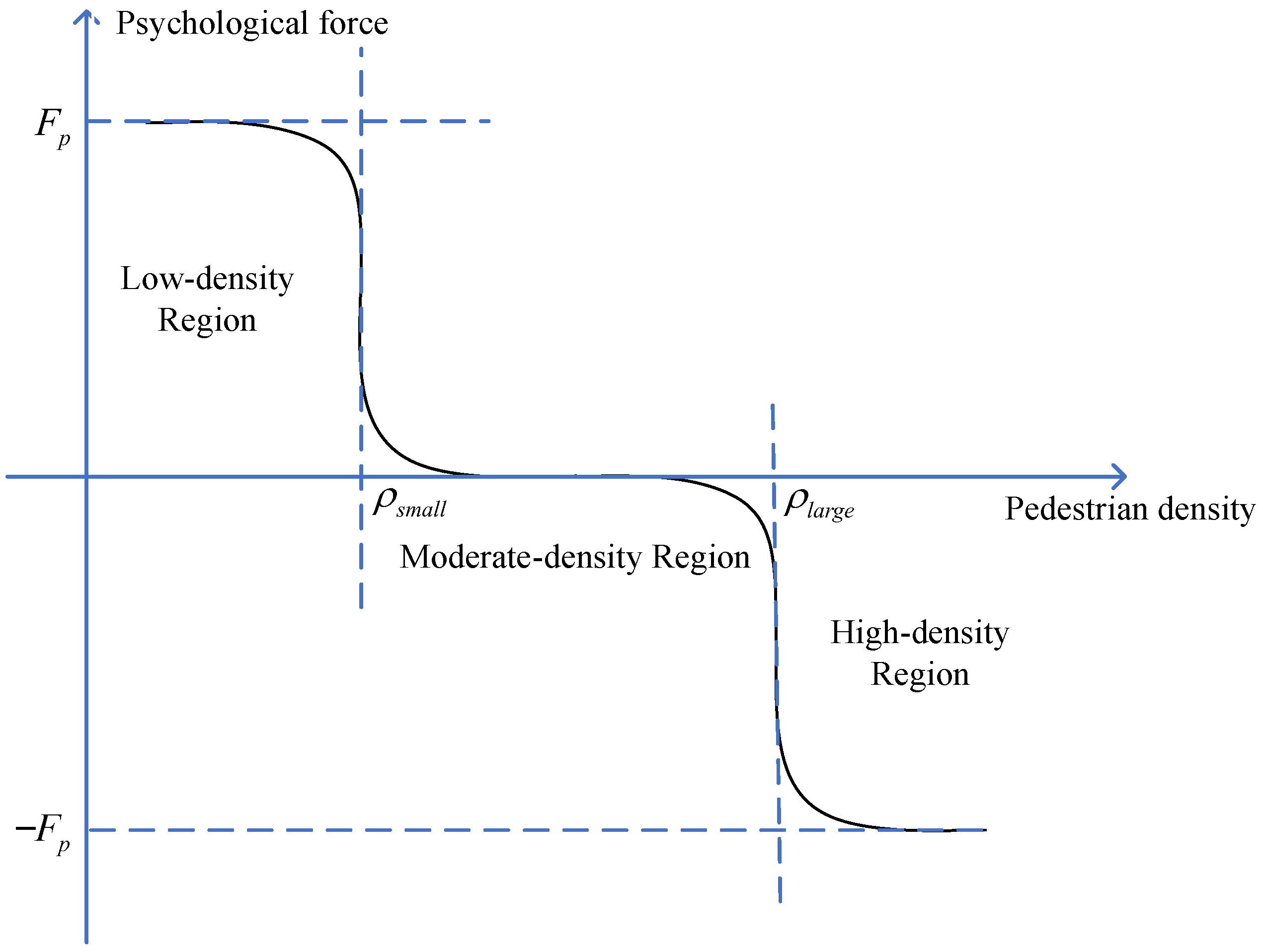

3.2. Pedestrian Classification and Model Modification

4. Microscopic Flow Features and Service Mode Switching Thresholds

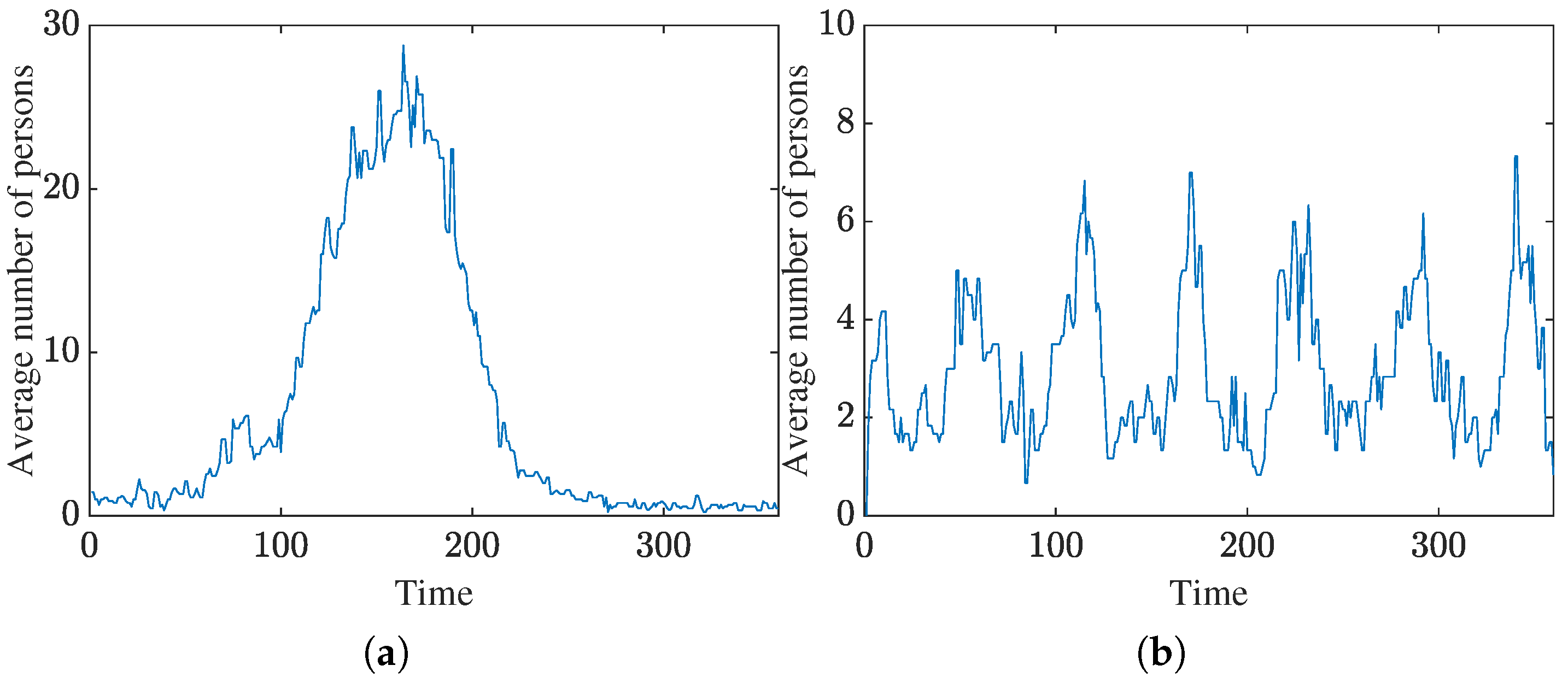

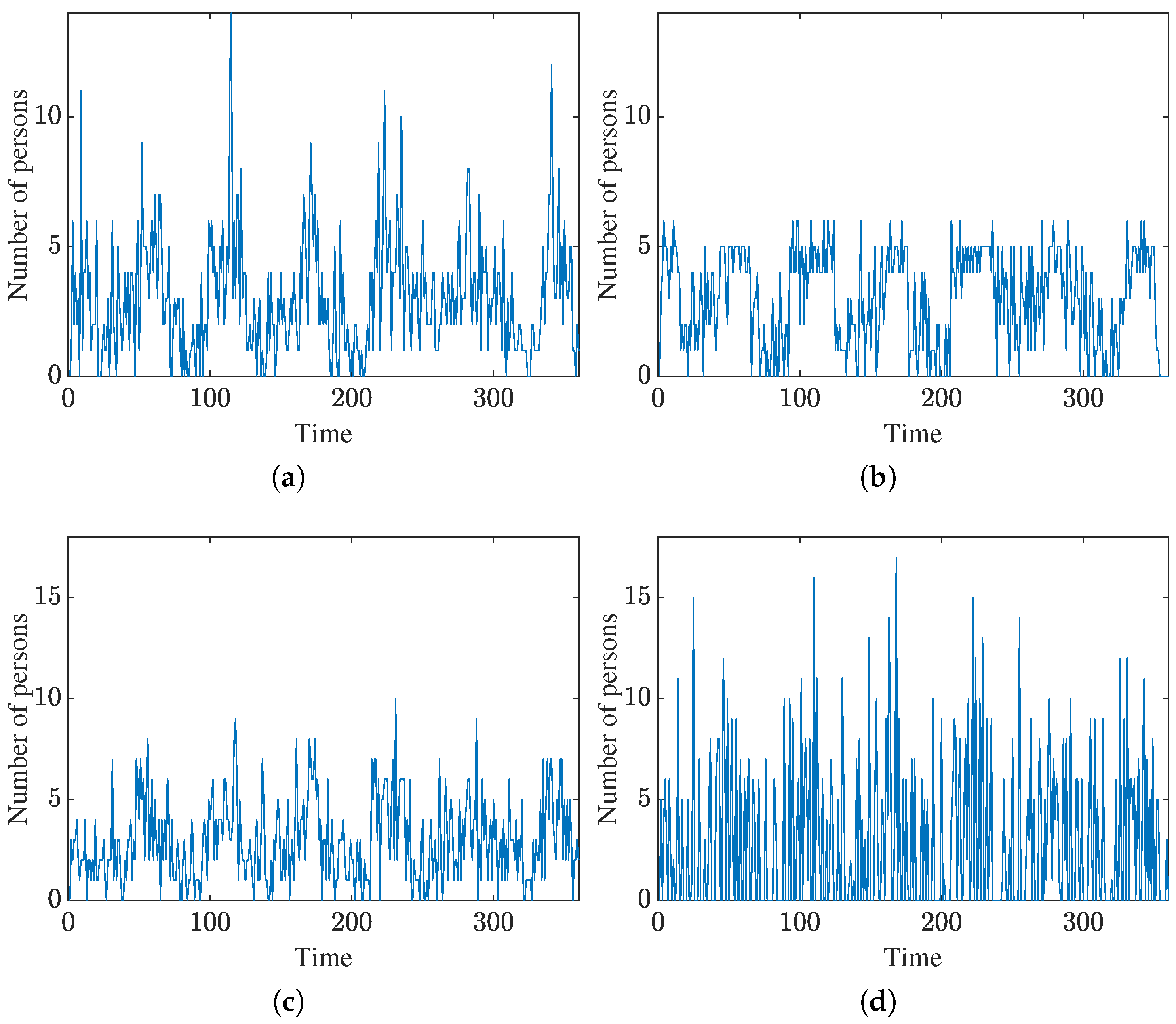

4.1. Flow Construction for Different Pedestrian Types

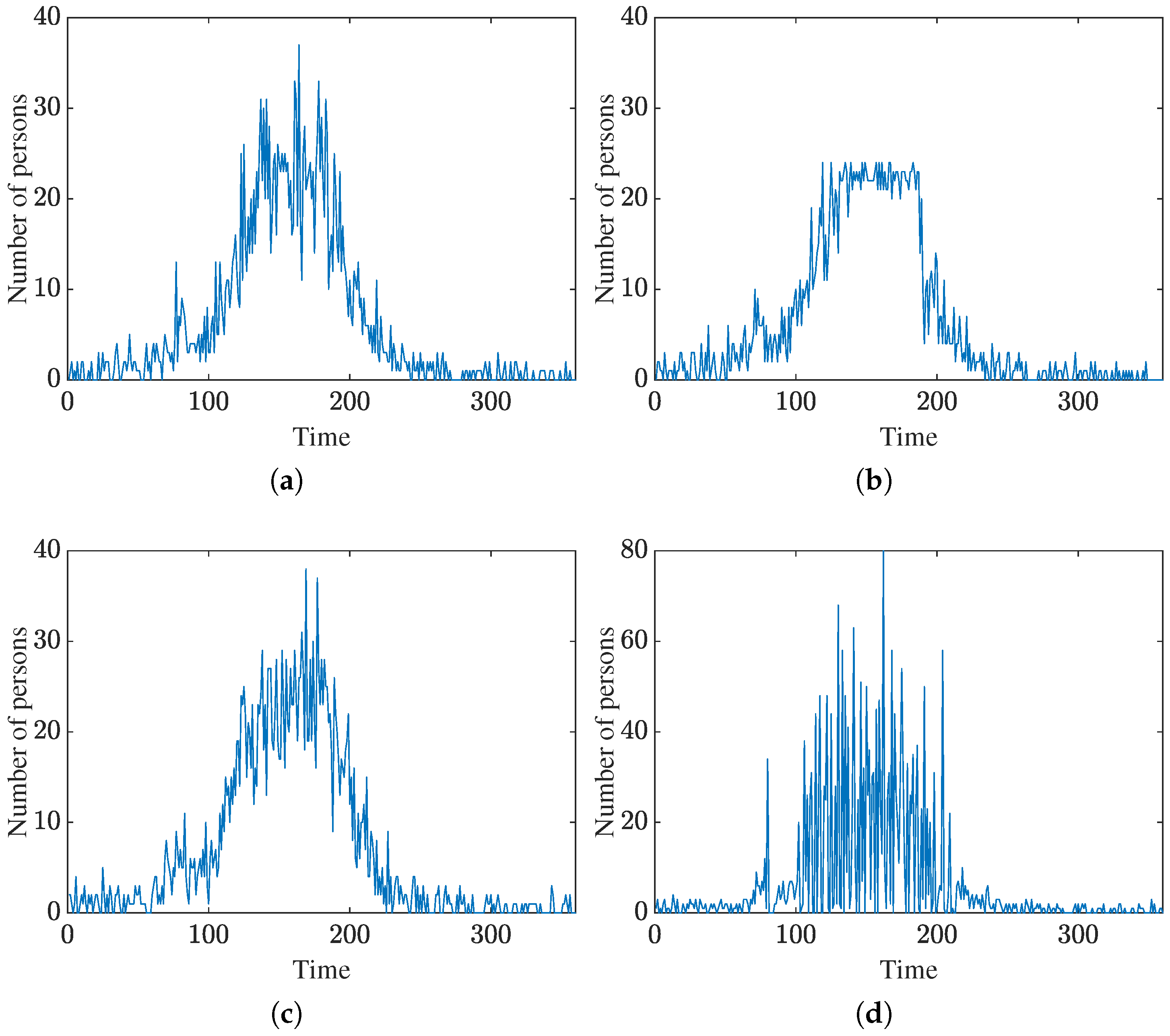

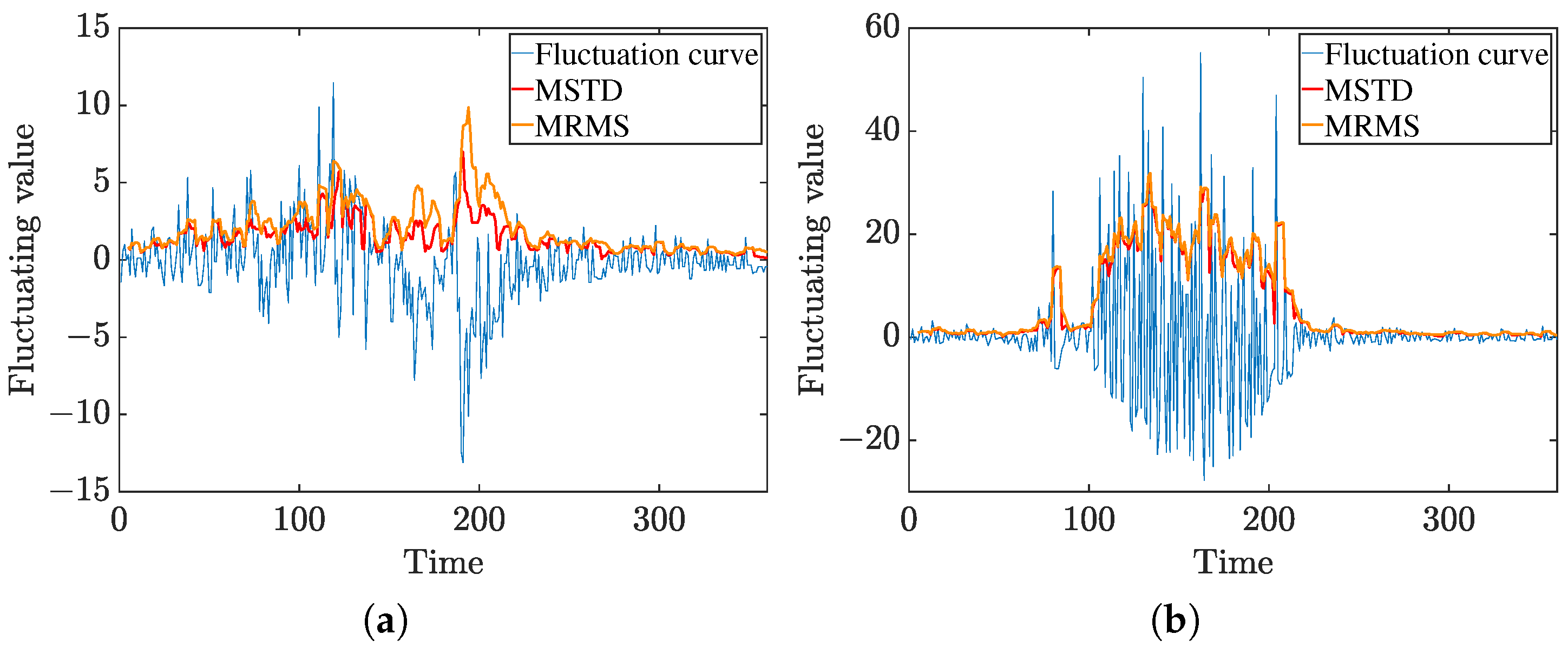

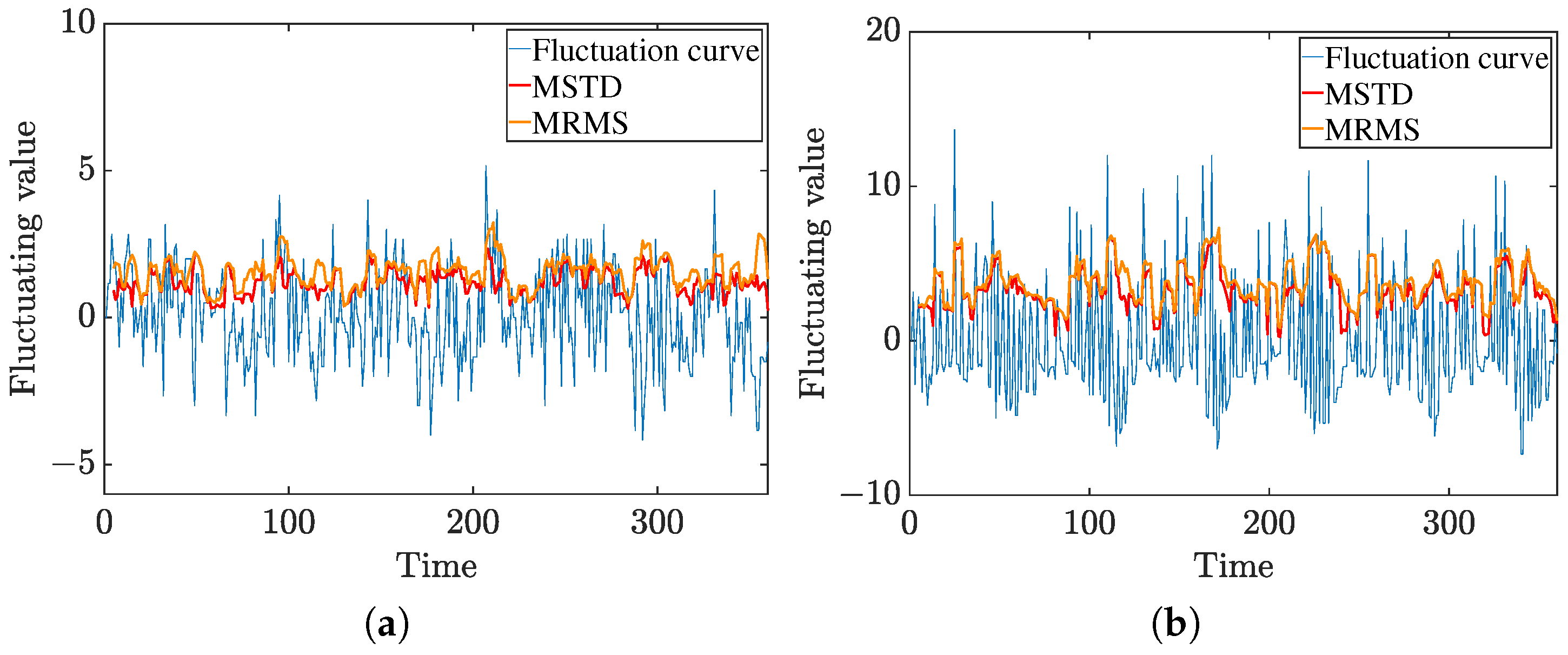

4.2. Microscopic Features of Various Types of Pedestrians

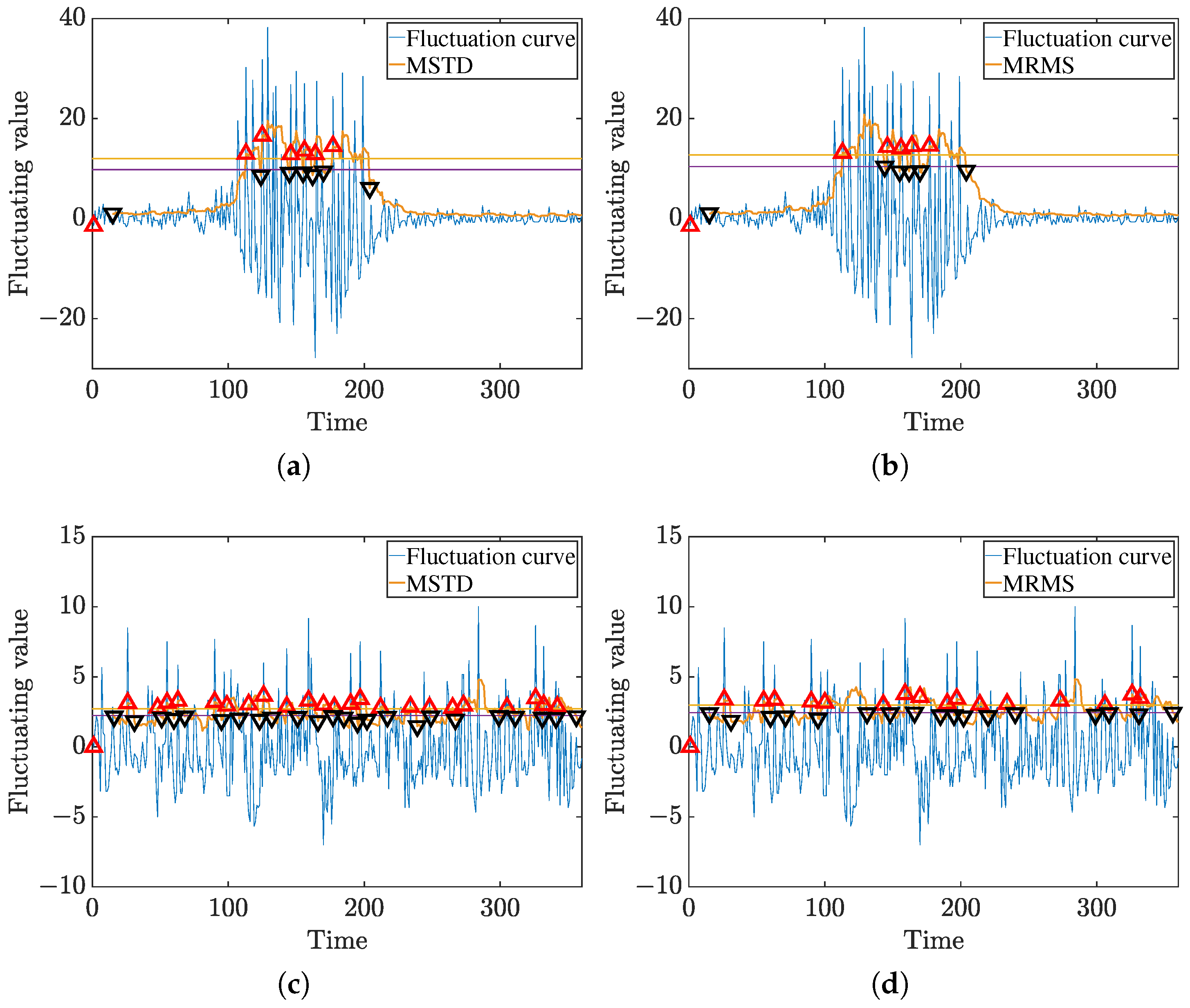

4.3. Determination of Service Mode Switching Thresholds

5. Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Method

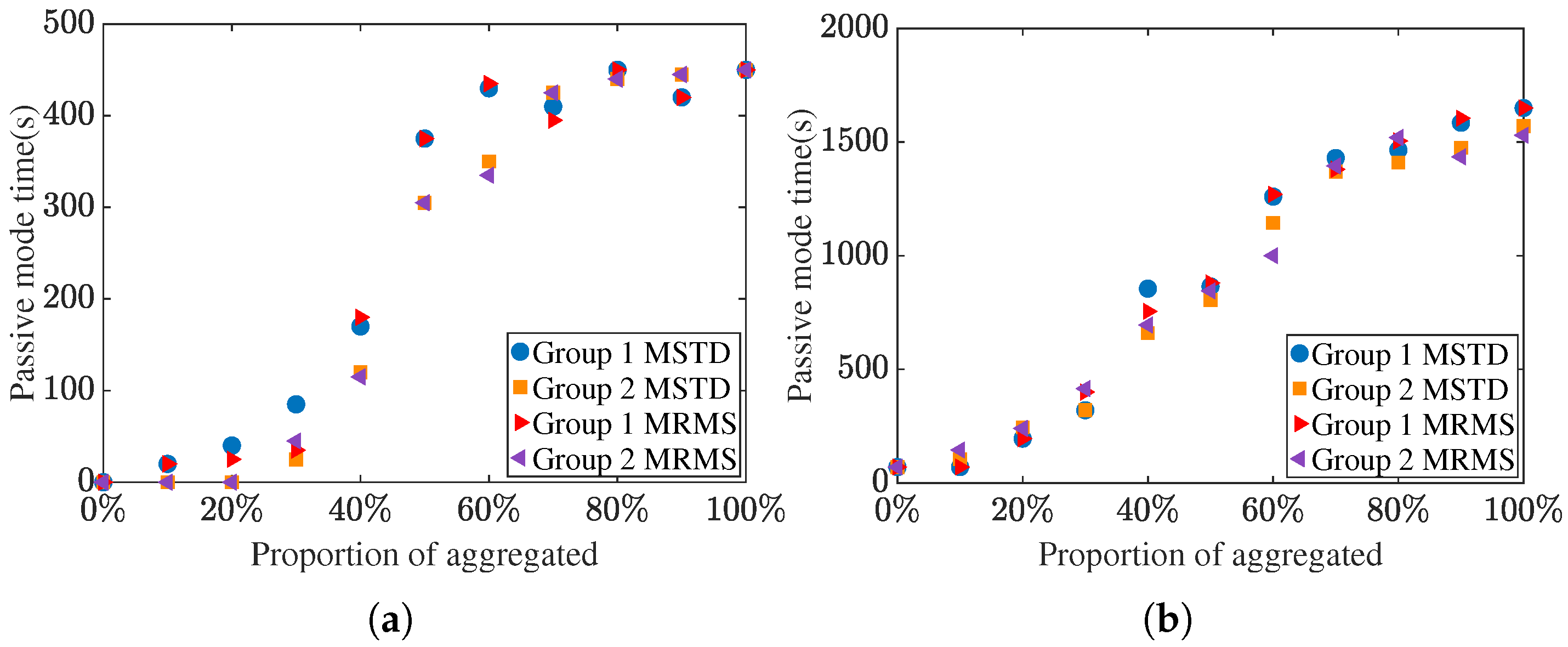

5.1. Threshold Robustness and Rationale Analysis

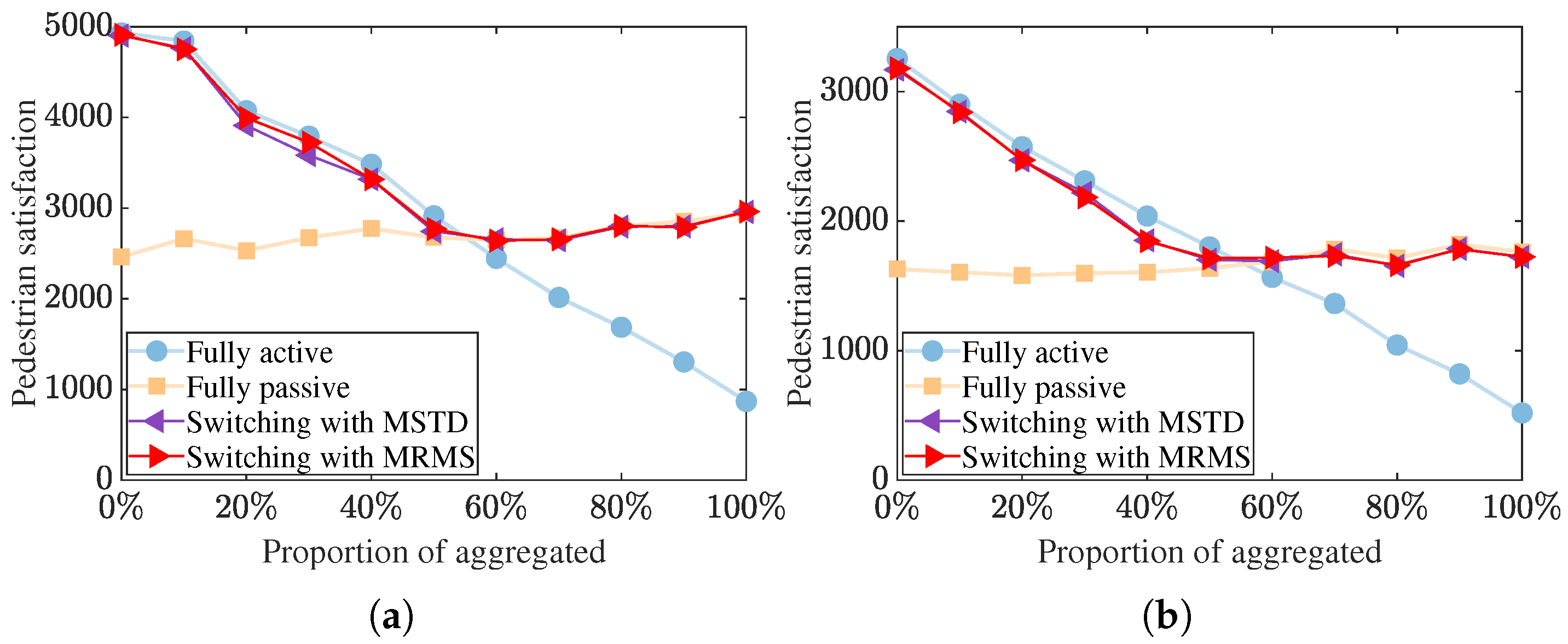

5.2. Service Satisfaction Improvement Through the Proposed Method

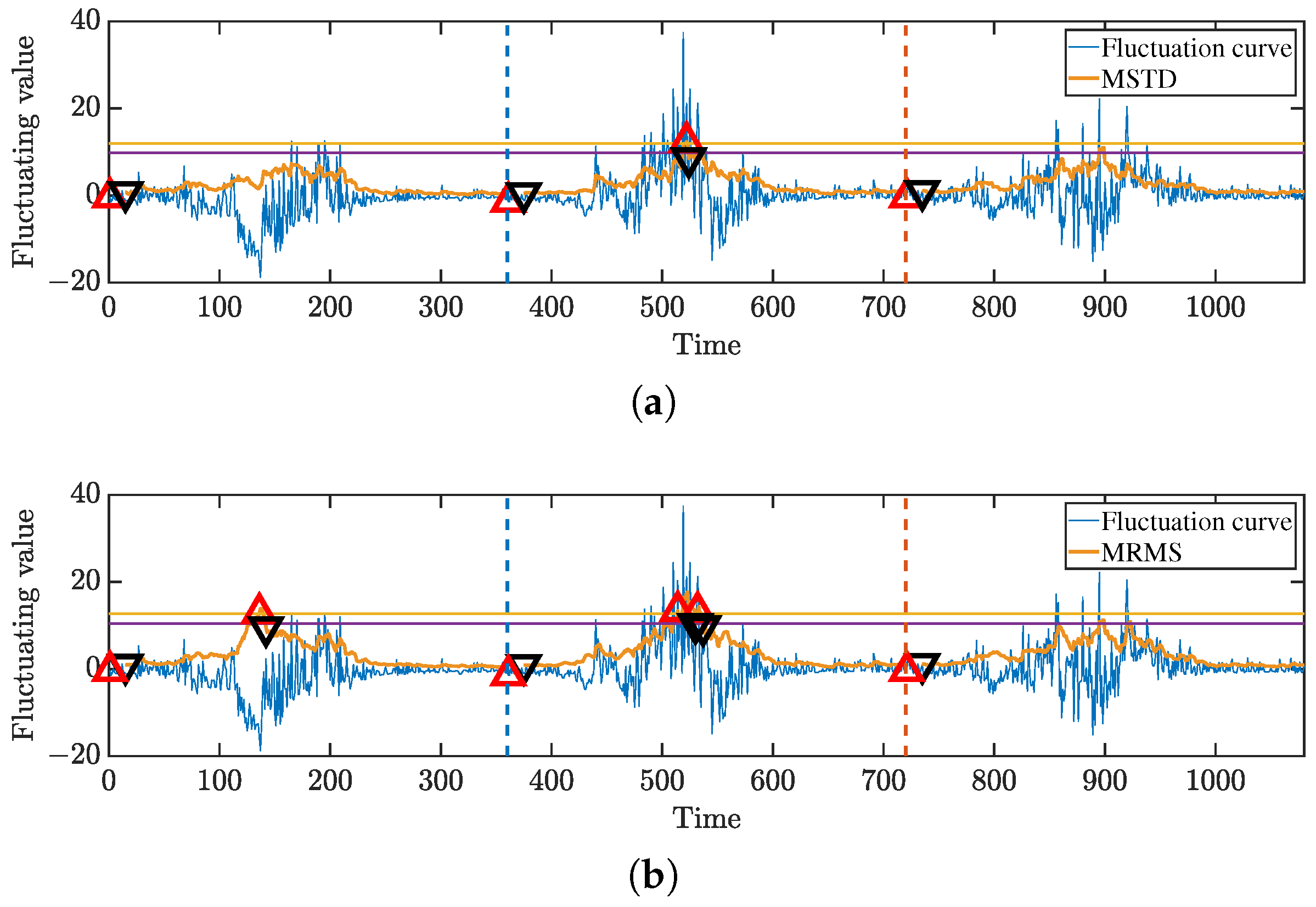

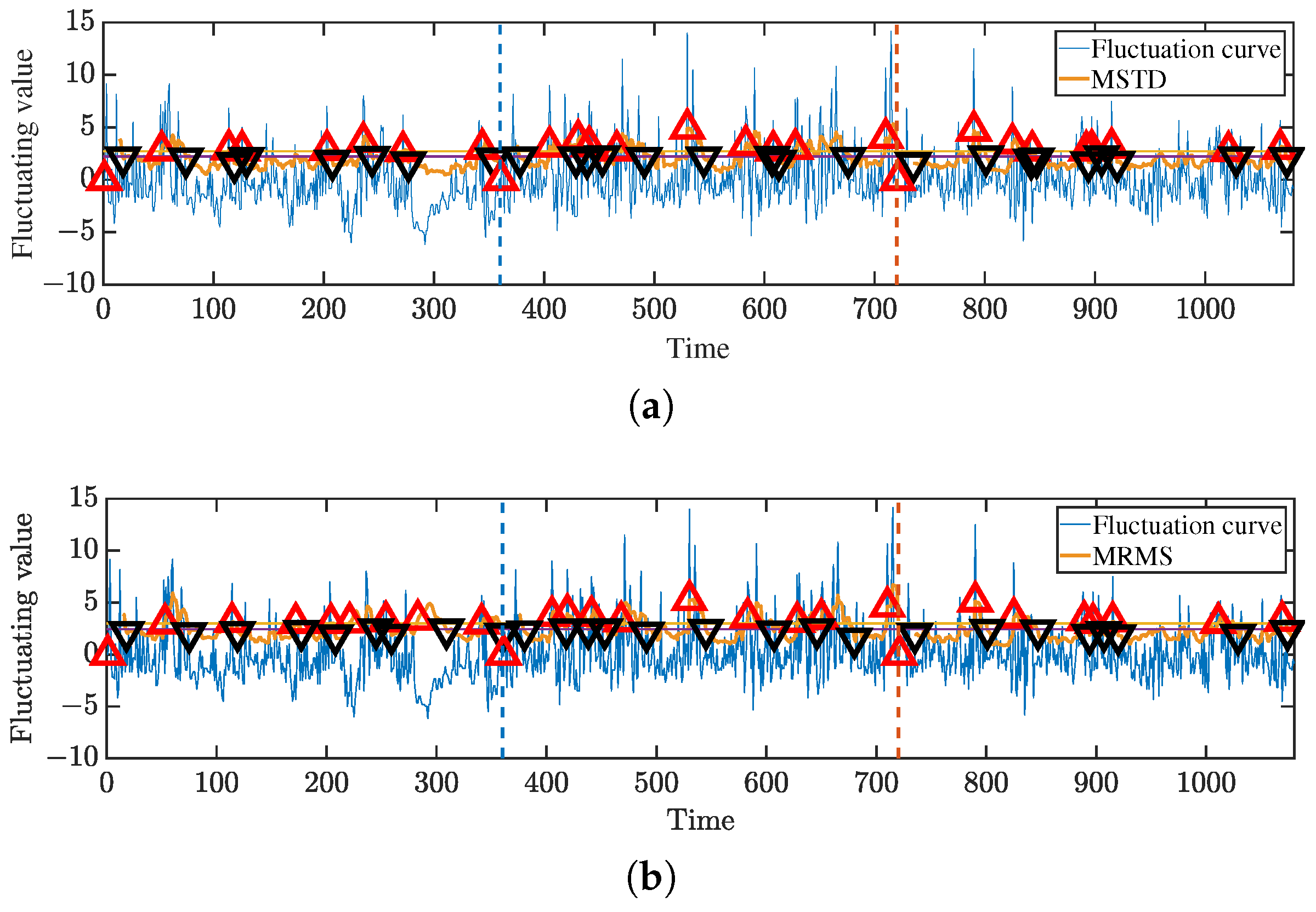

5.3. Identification of Switching Points in Real Pedestrian Flows

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, L.; Cai, R.; Gursoy, D. Developing and validating a service robot integration willingness scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghici, B.G.; Dobre, A.E.; Misaros, M.; Stan, O.P. Development of ahuman service robot application using pepper robot as a museum guide. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics (AQTR), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 19–21 May 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, J.D.; Domingo, G.C.B.; Garcia, R.G. Automated service robot for catering businesses using Arduino Mega 2560. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering (ICCAE), Sydney, Australia, 3–5 March 2023; pp. 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Repiso, E.; Garrell, A.; Sanfeliu, A. People’s adaptive side-by-side model evolved to accompany groups of people by social robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Cheng, X.; Pan, J.; Long, P.; Liu, W.; Yang, R.; Manocha, D. Getting robots unfrozen and unlost in dense pedestrian crowds. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-H.; Liu, F.-C.; Fu, L.-C. Active learning on service providing model: Adjustment of robot behaviors through human feedback. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2018, 10, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Chen, Z. Path planning of service robot based on improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Computer Engineering and Intelligent Communications (ISCEIC), Nanjing, China, 18–20 August 2023; pp. 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, K.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.; Song, S.; Meng, M. Human-aware path planning with improved virtual doppler method in highly dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 1304–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. Human-aware trajectory optimization for enhancing D* algorithm for autonomous robot navigation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 103237–103250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Cao, C.; Pan, J. A hierarchical approach for mobile robot exploration in pedestrian crowd. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Li, P. Parameter fuzzy self-adaptive dynamic window approach for local path planning of wheeled robot. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Huang, H.; Guo, S.; Chen, W.; Zheng, Z. QoS-aware cooperative computation offloading for robot swarms in cloud robotics. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 4027–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Mi, Z.; Yang, Y.; Obaidat, M. An energy sensitive computation offloading strategy in cloud robotic network based on GA. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 13, 3513–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Jin, J.; Cricenti, A.L.; Rahman, A.; Kulkarni, A. Communication-aware cloud robotic task offloading with on-demand mobility for smart factory maintenance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2500–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Peng, M.; Zhao, S. Resource optimization algorithm for task offloading of service robots with position prediction. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 10–13 December 2021; pp. 1047–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Wang, L.; Kai, C.; Peng, M. Resource optimization for task offloading with real-time location prediction in pedestrian-vehicle interaction scenarios. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 7331–7344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Q. Crowd hybrid model for pedestrian dynamic prediction in a corridor. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 95264–95273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Zheng, X. An extended social force model via pedestrian heterogeneity affecting the self-driven force. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 7974–7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G. Research on the model of road crossing based on pedestrian psychology. In Proceedings of the 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Kunming, China, 22–24 May 2021; pp. 6864–6868. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Ding, N.; Li, Y. A modified social force model for sudden attack evacuation based on Yerkes-Dodson law and the tendency toward low risk areas. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2024, 633, 129403–129420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.R.L.; Bhatia, A.; Brynjarsdóttir, J.; Abaid, N.; Barbaro, A.; Butail, S. Speed modulated social influence in evacuating pedestrian crowds. Coll Dyn 2020, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, J. A modified social force model with different categories of pedestrians for subway station evacuation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 110, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardimansyah; Ahyuna; Syam, A.; Salman; Ghani, A.D.; Natsir, M.S. Moving average and relative strength index indicators in determining open and closed positions on the metatrader4 expert advisor. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent System (ICORIS), Makasar, Indonesia, 25–26 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Khairi, T.W.A.; Zaki, R.M.; Mahmood, W.A. Stock price prediction using technical, fundamental and news based approach. In Proceedings of the 2nd Scientific Conference of Computer Sciences (SCCS), Baghdad, Iraq, 27–28 March 2019; pp. 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Wang, L.; Kai, C.; Peng, M. Index-based mode adjustment for energy saving of service vehicles and robots in vehicular networks. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 8–11 December 2023; pp. 1279–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Shan, R.; Wang, S. An intelligent rehabilitation robot with passive and active direct switching training: Improving intelligence and security of human-robot interaction systems. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2023, 30, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkar, M.; Kumar, D.; Sindha, J. Real-time pedestrians detection by YOLOv5. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kharagpur, India, 6–8 July 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D.; Farkas, I.; Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 2000, 407, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keirsey, D. Please Understand Me II: Temperament, Character, Intelligence; Prometheus Nemesis: Del Mar, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D.; Molnár, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 4282–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N) | 2000 | 0.08 | |

| 120,000 | 240,000 | ||

| (s) | 0.5 | [0.25, 0.35] | |

| (kg) | [60, 90] | [1.1, 1.5] | |

| (m) | 3 | 50 | |

| 0.15 (sci-tech buildings), 0.1 (subway station exit) | 0.2 (sci-tech buildings), 0.13 (subway station exit) |

| Location | Indicator | n | Dispersed | Aggregated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sci-tech buildings | MSTD | 5 | 2.4172 | 18.7560 |

| 15 | 3.0163 | 19.3523 | ||

| MRMS | 5 | 3.5567 | 19.4936 | |

| 15 | 3.6070 | 19.6428 | ||

| Subway station exit | MSTD | 5 | 1.2235 | 3.4053 |

| 15 | 1.4509 | 3.8241 | ||

| MRMS | 5 | 1.5487 | 3.7627 | |

| 15 | 1.5982 | 3.9446 |

| Mode Switching Methods | Mean of Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Sci-Tech Buildings | Subway Station Exit | |

| Fully active | 2942.0000 | 1835.7272 |

| Fully passive | 2700.2909 | 1674.6909 |

| Switching with MSTD | 3370.3454 | 2077.4181 |

| Switching with MRMS | 3392.9000 | 2077.0181 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Hu, W.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Li, W.; Peng, M. Service Mode Switching for Autonomous Robots and Small Intelligent Vehicles Using Pedestrian Personality Categorization and Flow Series Fluctuation. Information 2026, 17, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010043

Zhang P, Hu W, Wang L, Lin H, Li W, Peng M. Service Mode Switching for Autonomous Robots and Small Intelligent Vehicles Using Pedestrian Personality Categorization and Flow Series Fluctuation. Information. 2026; 17(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Peimin, Wanwan Hu, Lusheng Wang, Hai Lin, Weiping Li, and Min Peng. 2026. "Service Mode Switching for Autonomous Robots and Small Intelligent Vehicles Using Pedestrian Personality Categorization and Flow Series Fluctuation" Information 17, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010043

APA StyleZhang, P., Hu, W., Wang, L., Lin, H., Li, W., & Peng, M. (2026). Service Mode Switching for Autonomous Robots and Small Intelligent Vehicles Using Pedestrian Personality Categorization and Flow Series Fluctuation. Information, 17(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010043