Lightweight One-to-Many User-to-Sensors Authentication and Key Agreement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Limitations of Prior Scheme(s)

1.2. Our Contributions

- One-to-many with PFS, no Elliptic-Curve Cryptography (ECC) on sensors: a single ephemeral ECDH between user and gateway yields a secret session; sensors perform only hashing and AEAD, without any elliptic-curve operations.

- Per-sensor keys without network-wide secrets: we derive a short-lived group key , expand per-sensor, and deliver them via AEAD wraps under each sensor’s long-term key, thus removing any shared masking value.

- Augmented-PAKE login: the user login is hardened with an augmented PAKE, eliminating offline password guessing even if a smart card or server database is copied.

- Stateless DoS cookie: a MACed cookie authenticates the initiator before any heavyweight work at the gateway; sensors verify a cheap tag before state allocation.

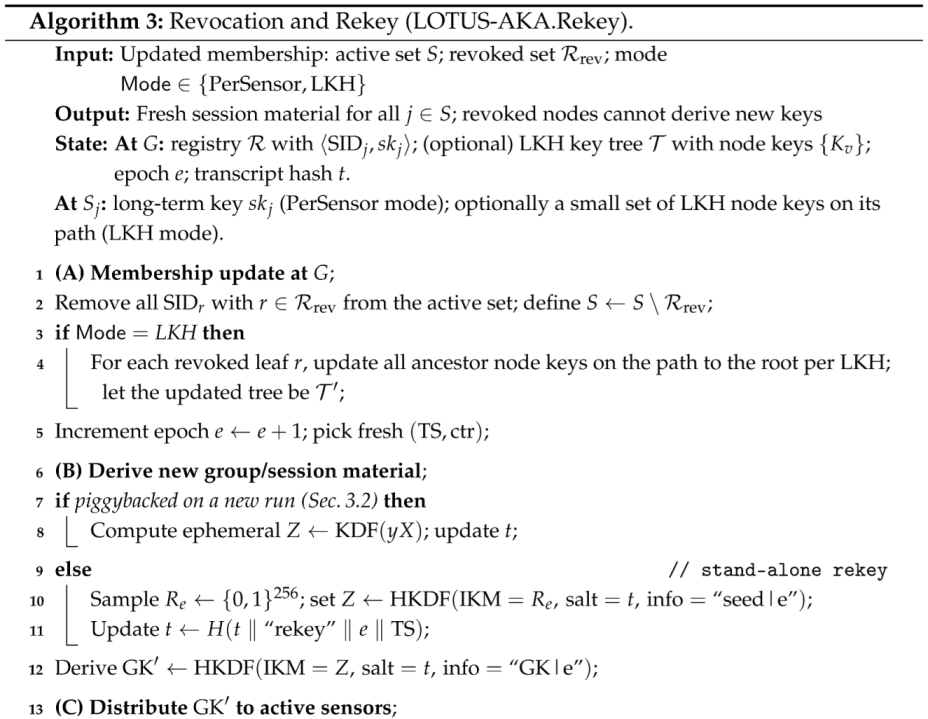

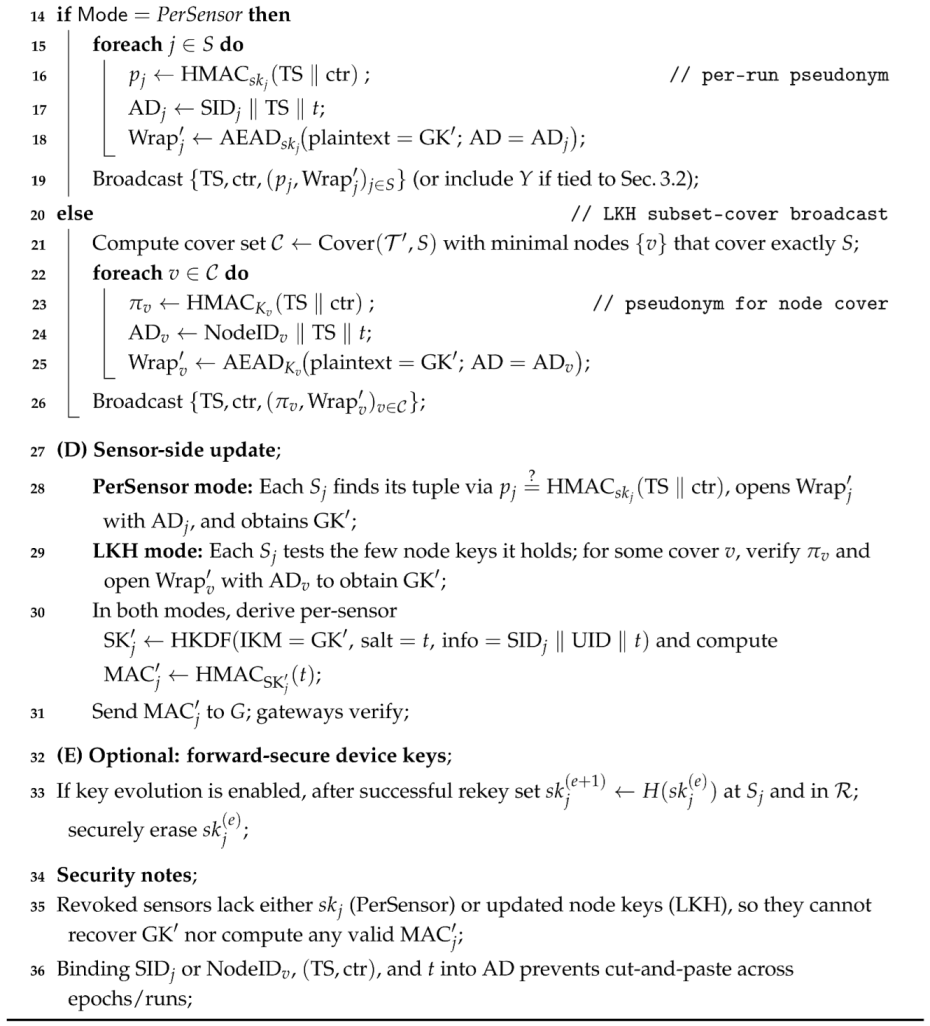

- Revocation and rekey: we provide a Logical Key Hierarchy (LKH)-style mechanism with subset wrapping to revoke sensors and rotate long-term keys with bounded broadcast cost.

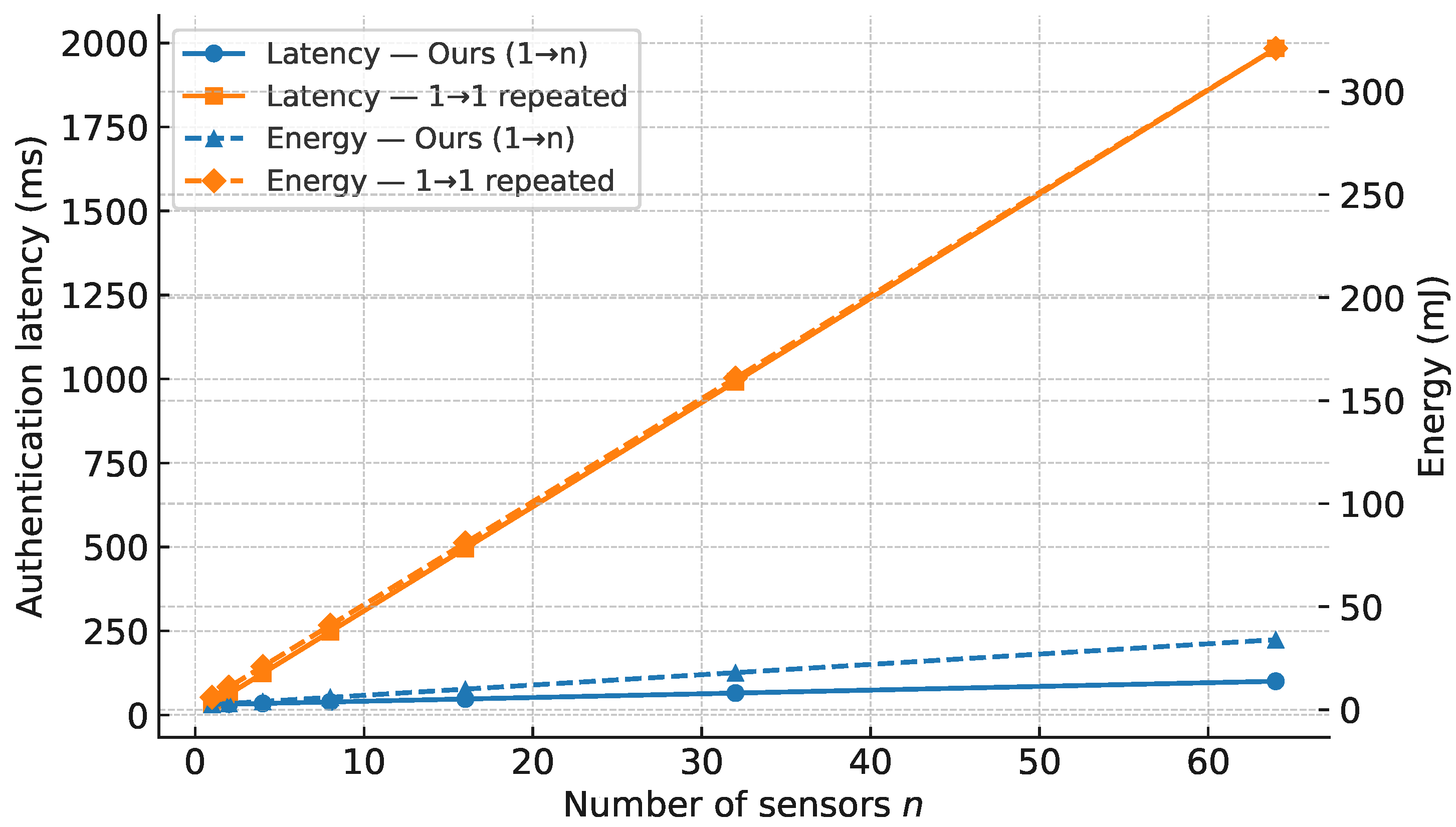

- Performance: measurements on Cortex-M–class Microcontroller Units (MCUs) show lower device computation and linear, low-constant communication/energy versus repeated one-to-one handshakes and recent one-to-many baselines.

2. Related Work

2.1. One-to-One AKE for Constrained Devices

2.2. Broadcast and Group-Oriented Authentication

2.3. Group Key Management and Subset Rekeying

2.4. Smart-Card and Multi-Server Authentication in IoT

2.5. DoS and Availability in Handshakes

2.6. Primitives on MCUs: AEAD and KDF

2.7. Positioning

3. Background and Preliminaries

3.1. Notation and Cryptographic Primitives

Security Assumptions and Proof Oracles

3.2. System and Trust Model

- : Output length of the hash (bits), e.g., .

- : Cryptographic hash (e.g., SHA-256).

- : Public identifier of sensor .

- : Gateway master secret.

- ‖: Byte-string concatenation.

- : Deterministic, injective byte encoding.

- : Local clock reading of node i at physical time t (seconds), assumed monotone.

- : Worst-case relative drift (frequency error) of clocks (e.g., in ppm).

- : Upper bound on the interval between (re-)synchronization events.

- : Residual clock offset immediately after a sync exchange (accounts for delay asymmetry).

3.3. Design Goals

- Mutual authentication between U and each via G.

- Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS) from an ephemeral ECDH between U and G.

- Key-compromise impersonation (KCI) resistance and key indistinguishability.

- Privacy: user anonymity and sensor unlinkability from public transcripts.

- Per-sensor confidentiality: even within one batch run, keys are isolated across sensors.

- Replay and DoS resistance: timestamps + nonces/counters, and a stateless MACed cookie that gates expensive work.

- Efficiency and scalability: sensors perform only hash/HMAC/AEAD; communication scales linearly with the number of addressed sensors with small constants.

- Revocation/rekey: operator can revoke sensors and rotate long-term material using a lightweight Logical Key Hierarchy (LKH) with subset wrapping.

4. Lightweight One-to-Many User-to-Sensors Authentication and Key Agreement (LOTUS-AKA) Protocol

4.1. Setup and Registration

| Algorithm 1: LOTUS-AKA Setup and Registration. |

State: Gateway registry initially empty 1 Gateway G: choose curve (P-256 or X25519) with base point P; sample master secret ; 2 Sensor registration (eachwith identifier ):;

3 ; store in (no network-wide key); 4 User registration/login (augmented PAKE, OPAQUE-style); 5 server stores a hardened PAKE record; user device/card stores an opaque envelope (no plaintext password); |

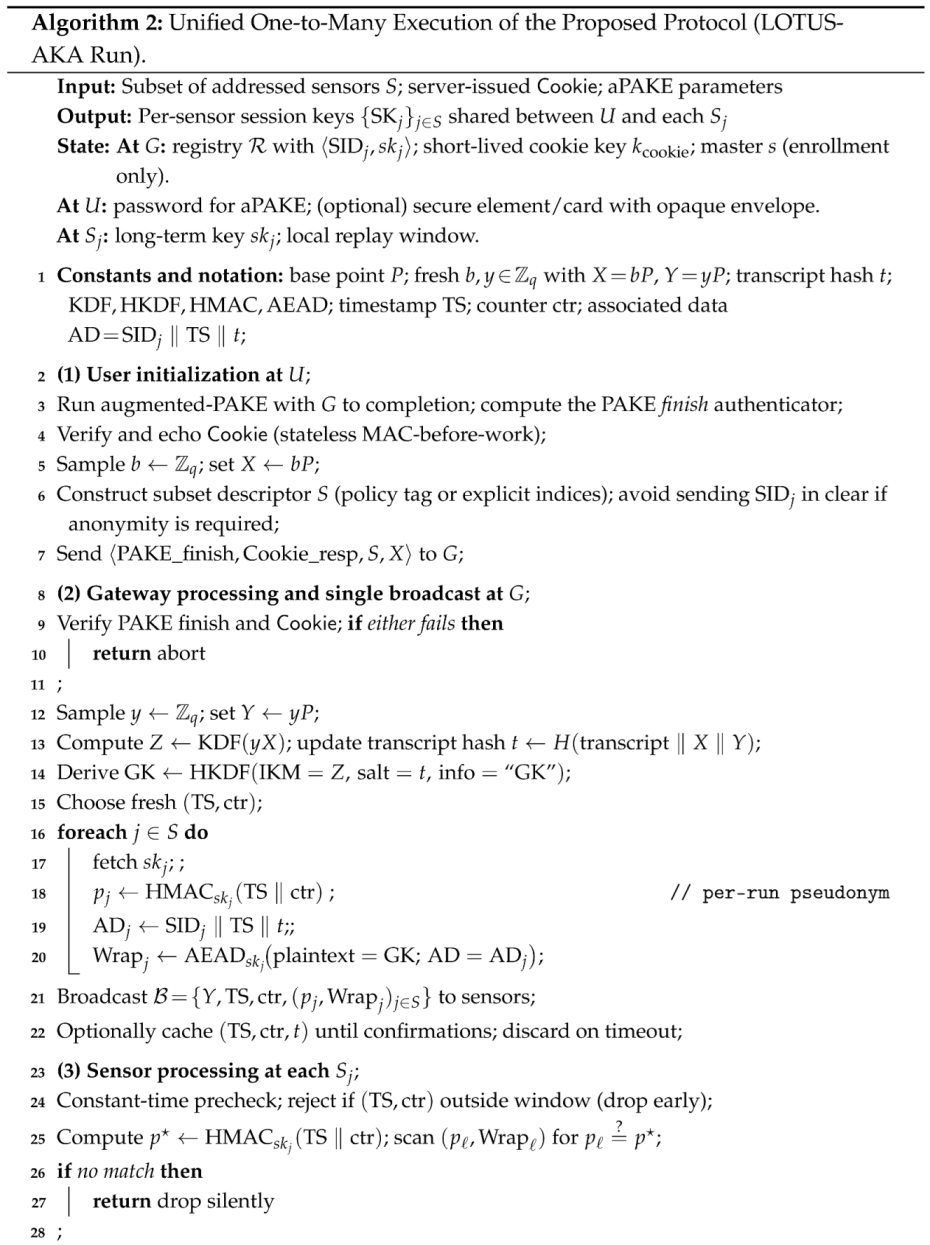

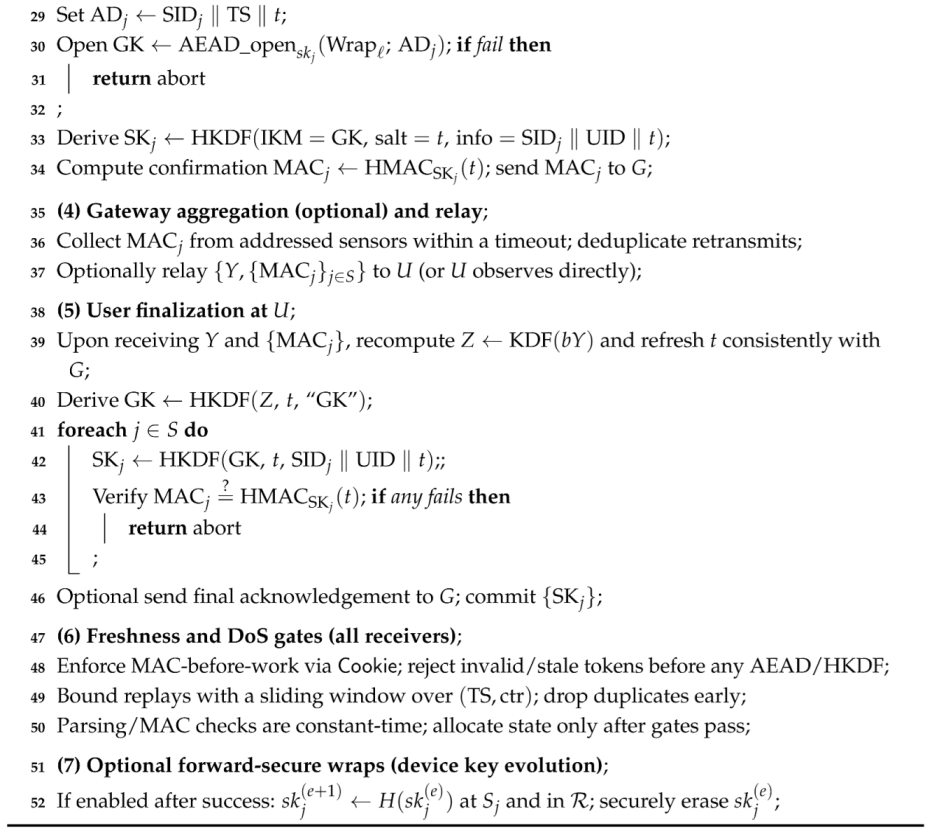

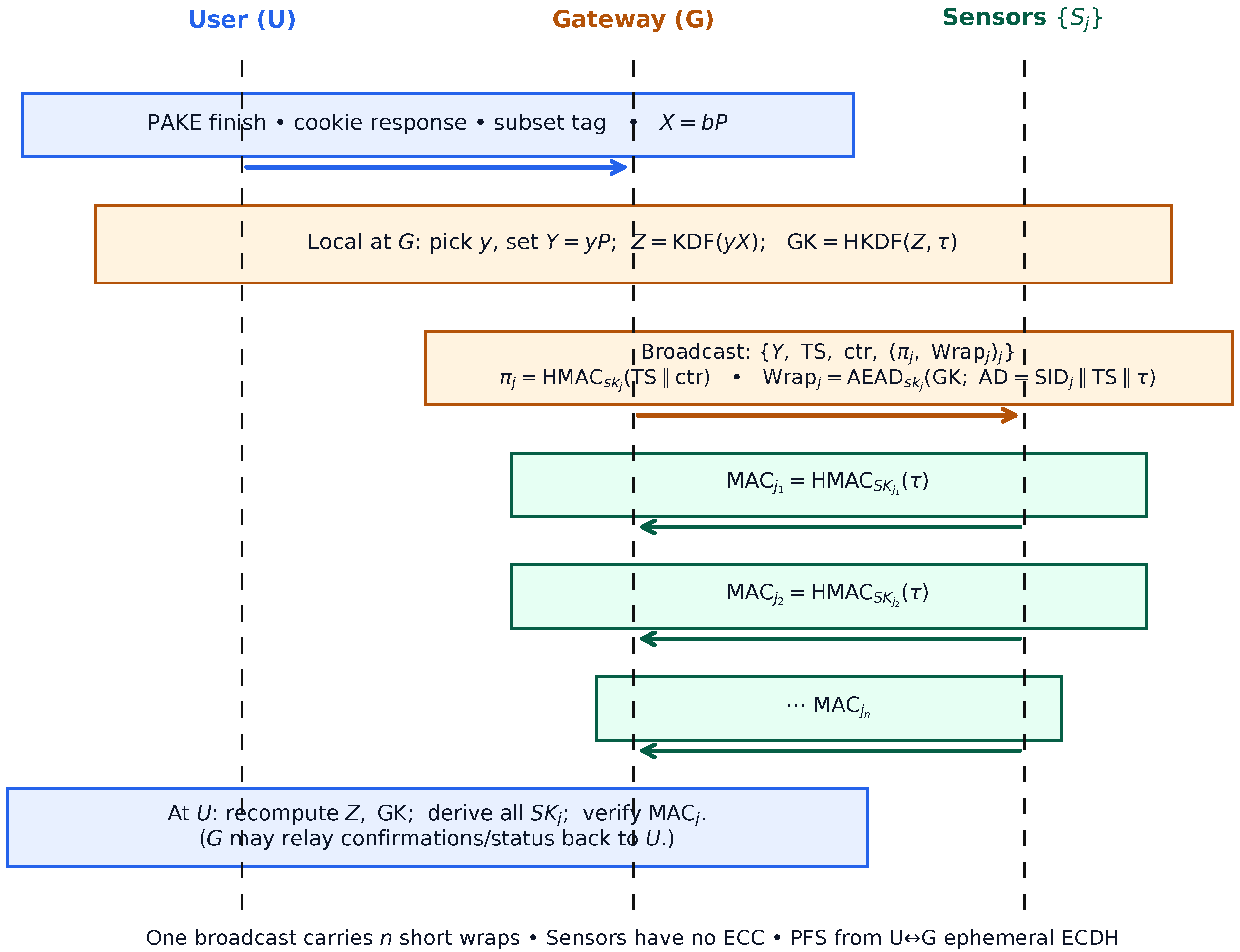

4.2. One-to-Many Authentication and Key Agreement

- (1)

- User → Gateway

- (2)

- Gateway processing

- (3)

- Per-sensor wrapping and broadcast

- (4)

- Sensor processing

- (5)

- User key confirmation

4.3. Rationale and Differences

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Proof Roadmap (Game-Based)

- denotes a probabilistic polynomial-time oracle machine that runs the AKE adversary as a subroutine and leverages its view/queries to attack an underlying primitive. The quantity is ’s success/advantage in the corresponding security game (standard in reduction-based proofs).

- : Security parameter; all algorithms are PPT in .

- : Adversary ’s AKE advantage in the /eCK indistinguishability experiment (distinguishing a fresh session key from uniform under the standard oracle interface).

- : Advantage of some PPT reduction in breaking the underlying PAKE security experiment (following BPR-style PAKE definitions).

- : PRF advantage of against the HMAC-based HKDF-Expand function (modeled as a keyed PRF on its input). Formally, , where F is HKDF-Expand and R is a random function.

- : AEAD advantage of against the symmetric cipher (aggregate of privacy IND-CPA/nonce-respecting and integrity INT-CTXT advantages for associated data).

- : Success probability of in solving the Computational Diffie–Hellman problem in the chosen group (given , output ).

- : A negligible function in .

5.2. Symbolic Verification

- Secrecy of for honest U, G, and any not explicitly corrupted as follows: query attacker(SK_j) == false.

- Authentication correspondence between U and each addressed : event end_U(j) implies event end_Sj(j) with matching transcript hash .

- Unlinkability of sensor sessions: observational equivalence between two traces that swap the identities of two honest sensors while preserving the multiset of messages.

5.3. DoS and Availability

6. Performance Evaluation

6.1. Metrics and Setup

6.2. Microbenchmarks

6.3. One-to-Many Baselines

6.3.1. B1: Shared Group-Key Broadcast (Single for All)

6.3.2. B2: LKH Subset Rekey (Distribute a Shared )

6.3.3. B3: Broadcast Authentication Only (no AKA)

6.4. Comparison with Baselines

6.5. Variants and Sensitivity Analysis

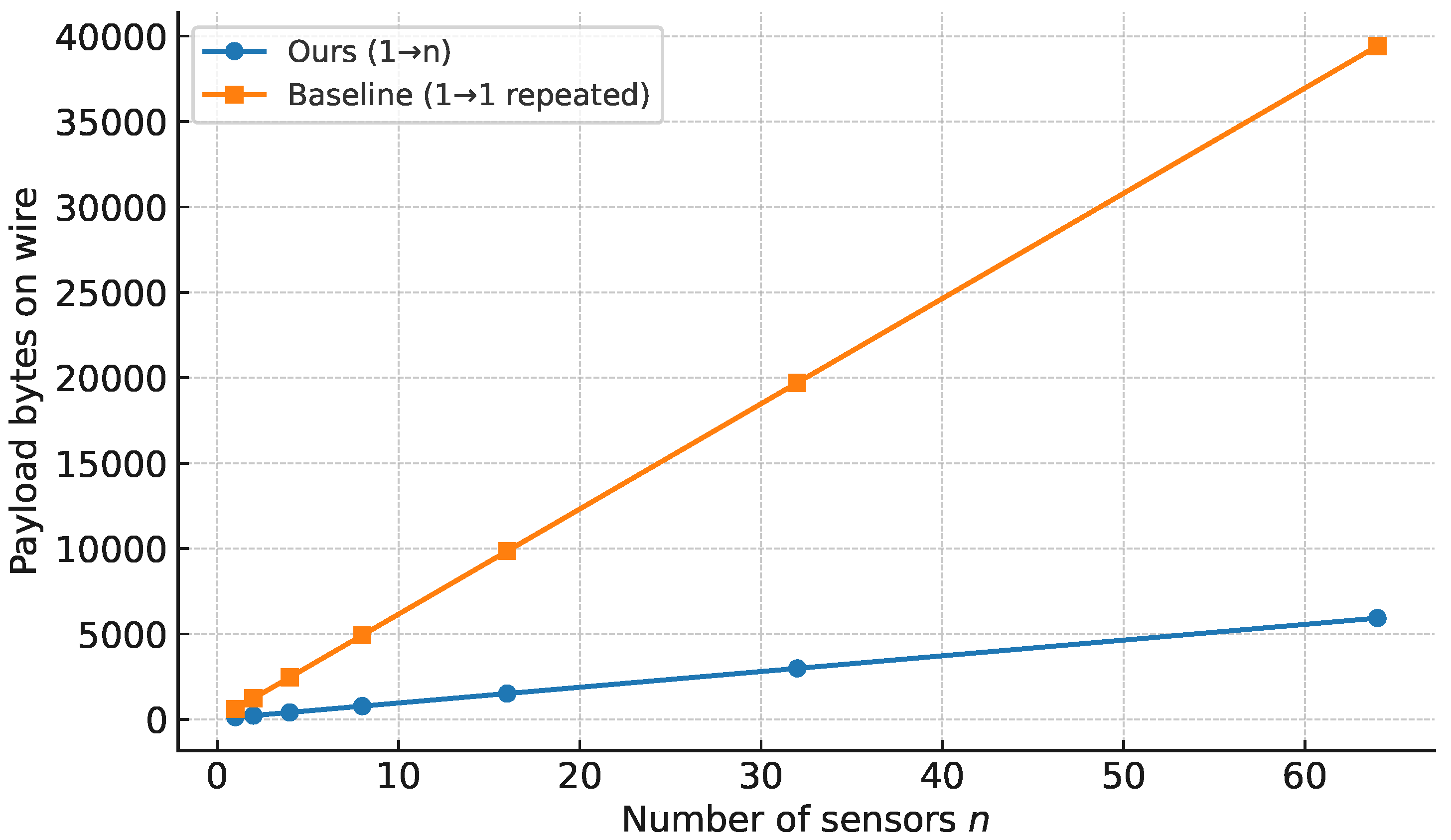

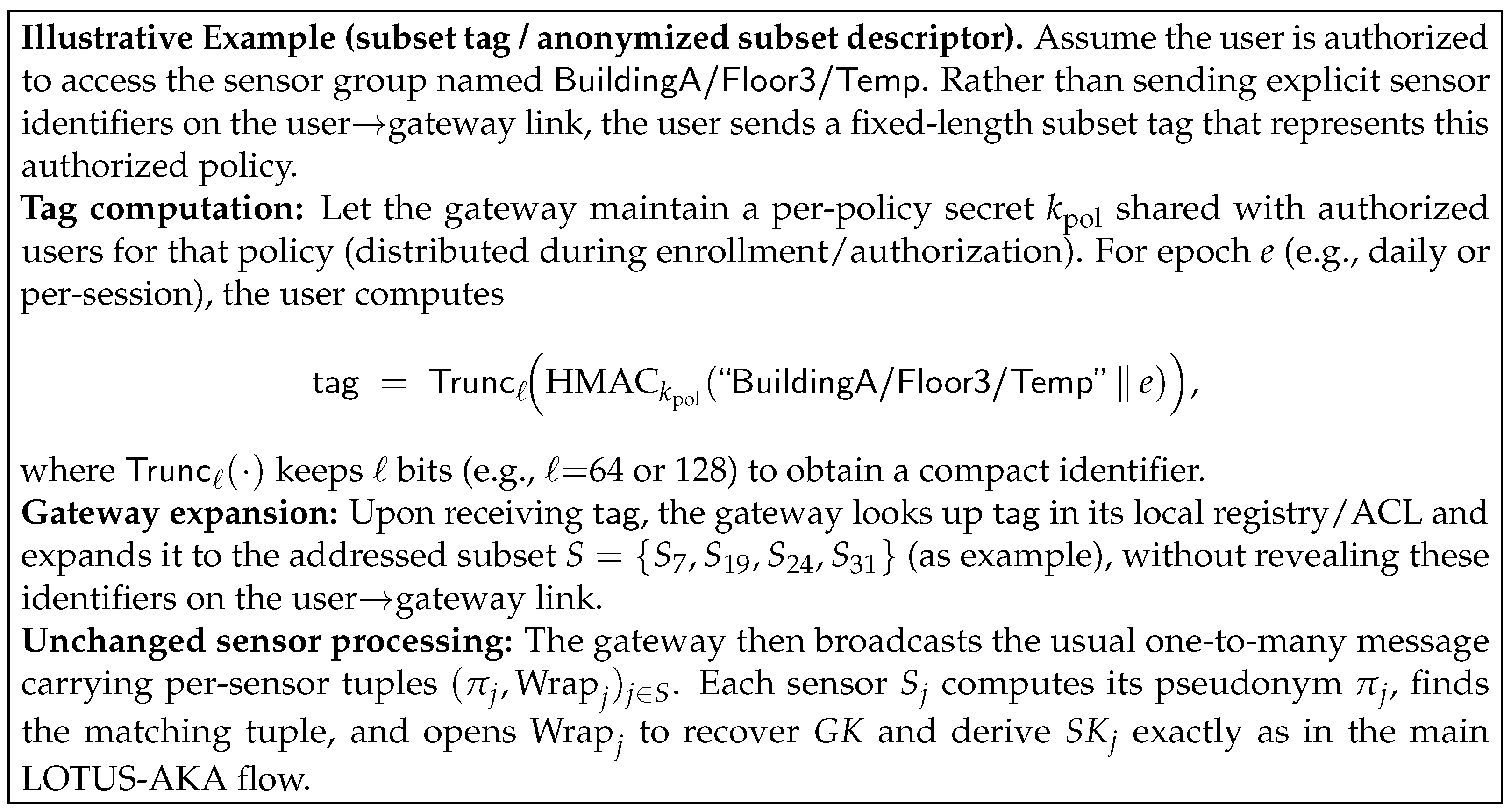

6.6. Communication Cost vs. n (Figure 4)

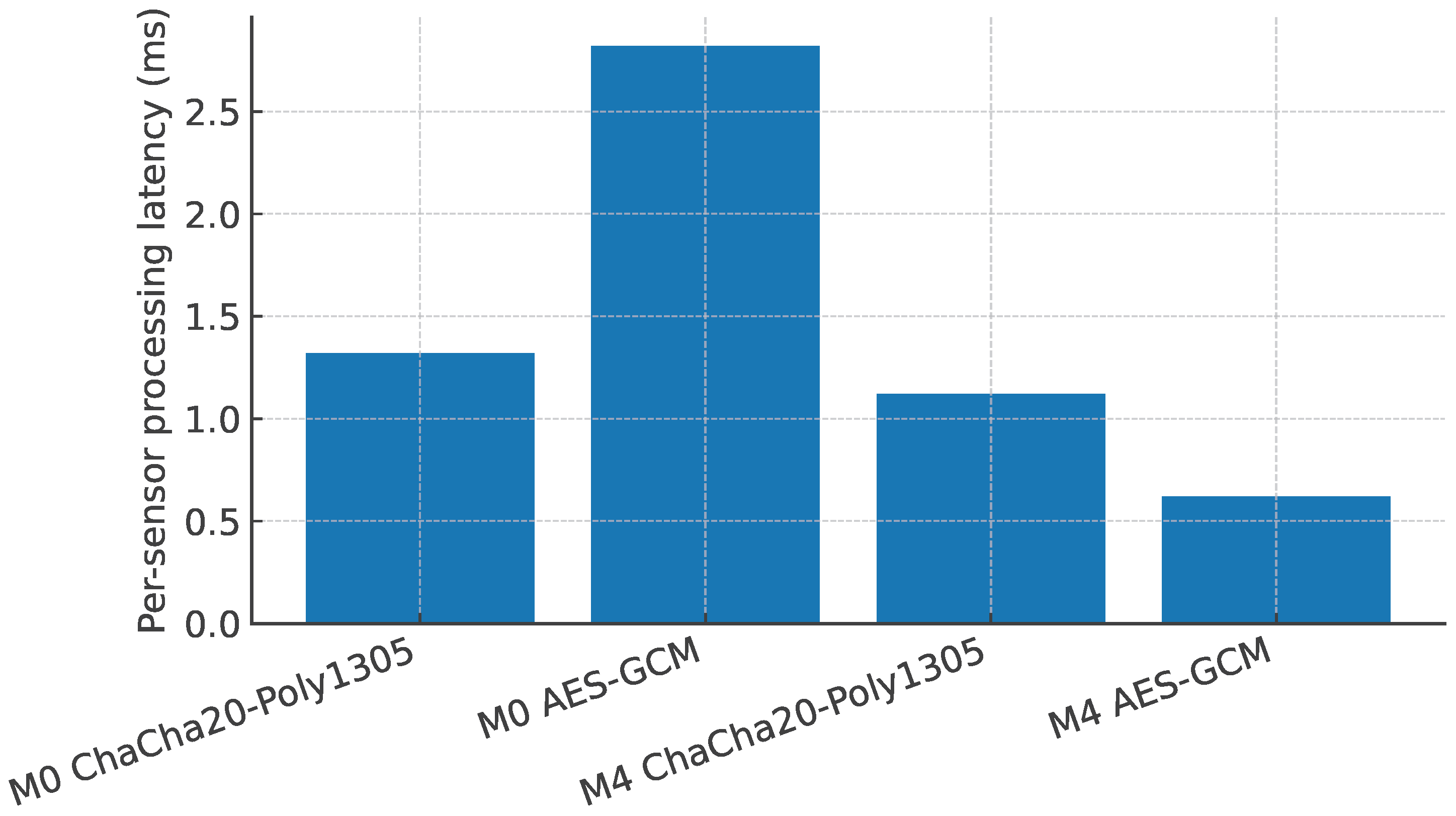

6.7. AEAD Choice on MCUs (Figure 5)

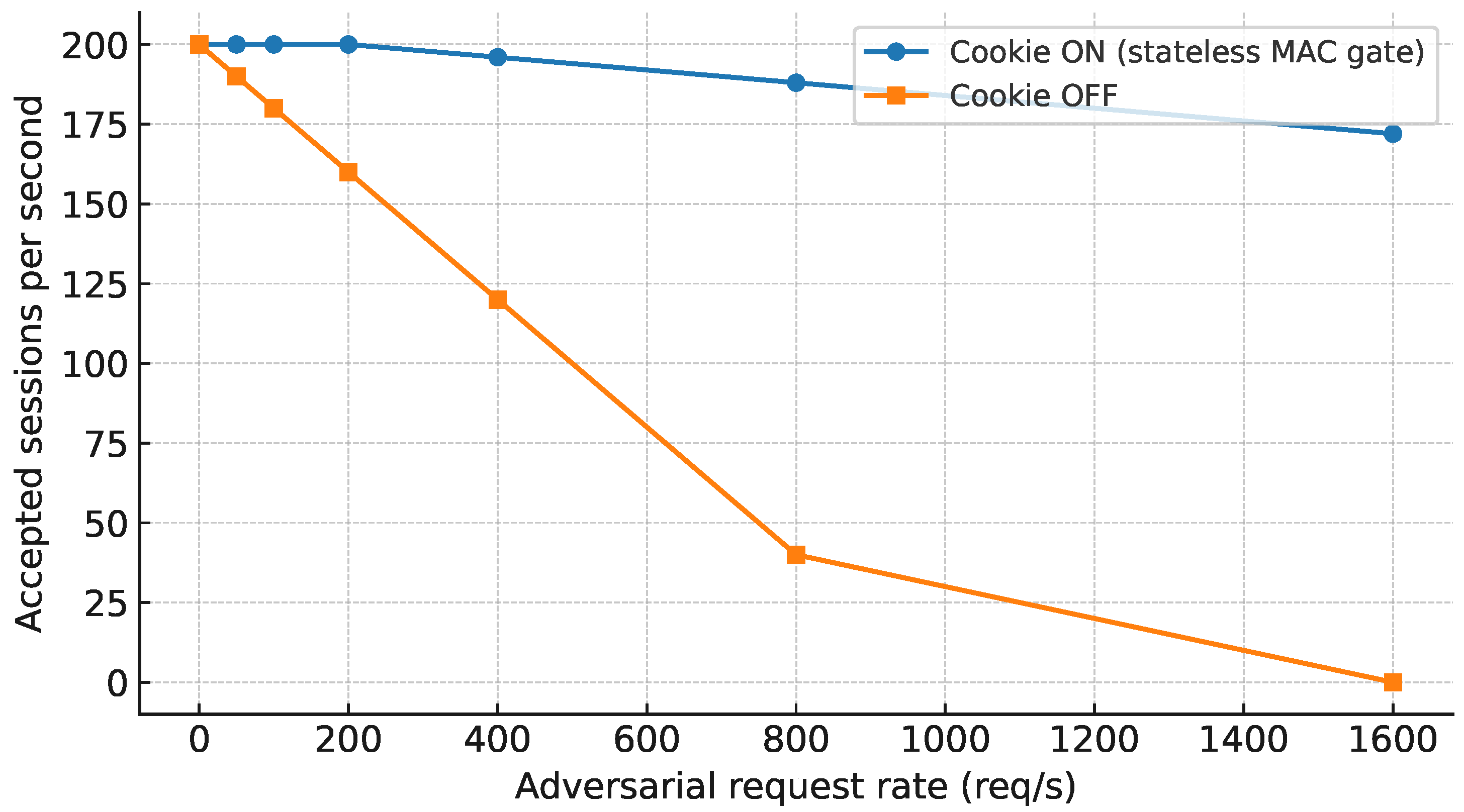

6.8. DoS Resilience Under Adversarial Load (Figure 6)

6.9. Authentication Latency and Energy vs. n (Figure 3)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perwej, Y.; Haq, K.; Parwej, F.; Mumdouh, M.; Hassan, M. The internet of things (IoT) and its application domains. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2019, 975, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, I.; Abolhasan, M.; Lipman, J.; Liu, R.P.; Ni, W. Anatomy of threats to the internet of things. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 21, 1636–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Kim, D.; Choo, H. Internet of everything: A large-scale autonomic IoT gateway. IEEE Trans.-Multi-Scale Comput. Syst. 2017, 3, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Weichen, Z.; Safie, N.; Ahmed, F.R.A.; Ghazal, T.M. A survey on key agreement and authentication protocol for internet of things application. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 61642–61666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiterau-Brostean, P.; Jonsson, B.; Merget, R.; De Ruiter, J.; Sagonas, K.; Somorovsky, J. Analysis of DTLS implementations using protocol state fuzzing. In Proceedings of the SEC’20: 29th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, Berkeley, CA, USA, 12–14 August 2020; pp. 2523–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Walz, A.; Sikora, A. Exploiting dissent: Towards fuzzing-based differential black-box testing of TLS implementations. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2017, 17, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Lin, W.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y. Coverage-guided differential testing of TLS implementations based on syntax mutation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbur, K.Y.; Tschorsch, F. QUICforge: Client-side Request Forgery in QUIC. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium 2023, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 February–3 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maleh, Y.; Ezzati, A.; Belaissaoui, M. Dos attacks analysis and improvement in dtls protocol for internet of things. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data and Advanced Wireless Technologies, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria, 10–11 November 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzoglou, E.; Kouliaridis, V.; Karopoulos, G.; Kambourakis, G. Revisiting QUIC attacks: A comprehensive review on QUIC security and a hands-on study. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Das, A.K.; Odelu, V.; Kumar, N.; Conti, M.; Jo, M. Design of secure user authenticated key management protocol for generic IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoth, R.; Deborah, L.J.; Vijayakumar, P.; Das, M.L.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Alazab, M. Secure multifactor authenticated key agreement scheme for industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algubili, B.H.T.; Kumar, N.; Lu, H.; Yassin, A.A.; Boussada, R.; Mohammed, A.J.; Liu, H. EPSAPI: An efficient and provably secure authentication protocol for an IoT application environment. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2022, 15, 2179–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B. A one-to-many authentication and key agreement scheme based on the sliding window. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communication Engineering (HPCCE 2024), Suzhou, China, 22–24 November 2025; Volume 13630, p. 1363002. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, Y.; Yang, P.; Mahdikhani, H.; Lu, R. A secure one-to-many authentication and key agreement scheme for industrial IoT. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 2225–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.H.; Ghalwash, A.T.E.F.; Nasr, M.O.N.A.; El-Hafez, A.A. A new lightweight authenticated key agreement protocol for IoT in cloud computing. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2021, 16, 3987–4005. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, R.M.; Thomas, A.; Rajsingh, E.B.; Silas, S. A Strengthened eCK Secure Identity Based Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol based on the Standard CDH Assumption. Inf. Comput. 2023, 294, 105067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.; Schmidt, B.; Cremers, C.; Basin, D. The TAMARIN Prover for the Symbolic Analysis of Security Protocols. In Proceedings of CAV 2013 (LNCS 8044); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescorla, E.; Modadugu, N. RFC 6347: Datagram Transport Layer Security Version 1.2; RFC Editor: USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc6347.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Rescorla, E.; Tschofenig, H.; Modadugu, N. RFC 9147: The Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS) Protocol Version 1.3; RFC Editor: USA, 2022; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc9147/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Selander, G.; Mattsson, J.; Palombini, F.; Seitz, L. RFC 8613: Object Security for Constrained RESTful Environments (OSCORE); RFC Editor: USA, 2019; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc8613/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Selander, G.; Preuß Mattsson, J.; Palombini, F. RFC 9528: Ephemeral Diffie–Hellman Over COSE (EDHOC); RFC Editor: USA, 2024; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc9528/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Perez, E.L.; Seler, G.; Mattsson, J.P.; Watteyne, T.; Vučinić, M. EDHOC Is a New Security Handshake Standard: An Overview of Security Analysis. Computer 2024, 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombini, F.; Tiloca, M.; Höglund, R.; Hristozov, S.; Selander, G. RFC 9668: Using Ephemeral Diffie-Hellman Over COSE (EDHOC) with the Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) and Object Security for Constrained RESTful Environments (OSCORE); RFC Editor: USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc9668.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Weng, Y.; Zhang, Y. A survey of secure time synchronization. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y. Research on SSL/TLS Security Differences Based on RFC Documents. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), IEEE Computer Society, Big Island, HI, USA, 19–22 Feburary, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.K.; Gouda, M.; Lam, S.S. Secure Group Communications Using Key Graphs. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2000, 8, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, M.; Naor, D.; Lotspiech, J. Revocation and Tracing Schemes for Stateless Receivers. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2001; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, C.; Hoffman, P.; Nir, Y.; Eronen, P.; Kivinen, T. RFC 7296: Internet Key Exchange Protocol Version 2 (IKEv2); RFC Editor: USA, 2014; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc7296 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Iyengar, J.; Thomson, M. RFC 9000: QUIC: A UDP-Based Multiplexed and Secure Transport; RFC Editor: USA, 2021; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.17487/RFC9000 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Nir, Y.; Langley, A. RFC 8439: ChaCha20 and Poly1305 for IETF Protocols; RFC Editor: USA, 2018; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc8439/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Dworkin, M. Recommendation for block cipher modes of operation. NIST Spec. Publ. 2001, 800, 38B. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, H.; Eronen, P. RFC 5869: HMAC-based Extract-and-Expand Key Derivation Function (HKDF); RFC Editor: USA, 2010; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5869 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Langley, A.; Hamburg, M.; Turner, S. RFC 7748: Elliptic Curves for Security; RFC Editor: USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc7748.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Biryukov, A.; Dinu, D.; Khovratovich, D.; Josefsson, S. RFC 9106: Argon2 Memory-Hard Function for Password Hashing and Proof-of-Work Applications; RFC Editor: USA, 2021; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc9106/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Biryukov, A.; Dinu, D.; Khovratovich, D. Argon2: New generation of memory-hard functions for password hashing and other applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Saarbruecken, Germany, 21–24 March 2016; pp. 292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdrez, D.; Krawczyk, H.; Lewi, K.; Wood, C.A. RFC 9807: The OPAQUE Augmented Password-Authenticated Key Exchange (aPAKE) Protocol; RFC Editor: USA, 2025; Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc9807 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Jarecki, S.; Krawczyk, H.; Xu, J. OPAQUE: An asymmetric PAKE protocol secure against pre-computation attacks. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tel Aviv, Israel, 29 April–3 May 2018; pp. 456–486. [Google Scholar]

- Canetti, R.; Krawczyk, H. Analysis of key-exchange protocols and their use for building secure channels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Innsbruck, Austria, 6–10 May 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 453–474. [Google Scholar]

- LaMacchia, B.; Lauter, K.; Mityagin, A. Stronger security of authenticated key exchange. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Provable Security, Wollongong, Australia, 1–2 November 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

| Protocol/Family | MutAuth | PFS | Per-Sens Iso | KCI | Privacy | OffDict | DoS | ECC@Sens | Comm. vs. n | Revoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTLS 1.3 (1 → 1) [20] | Y | Y | – | Y | ∼ | Y (no card) | Y | optional | (repeat) | – |

| EDHOC+OSCORE (1 → 1) [22,24] | Y | Y | – | Y | ∼ | Y (no card) | via CoAP | optional | (repeat) | – |

| TESLA-style broadcast [25] | auth. only | ∼ | N | – | N | – | N | Y (none) | sender meta | ∼ |

| Group key w/masking (typical) | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y (none) | wraps | ∼ |

| Smart-card multi-server (typical) | Y | N | N | N | ∼ | N | N | Y (none) | ∼ | |

| LKH subset rekey [26,27,28] | – | ∼ | ∼ | – | N | – | N | Y (none) | rekey | Y |

| LOTUS-AKA (this work) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y (none) | Y (via LKH) |

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| G | Base point of P–256/X25519 group |

| Private scalar , public | |

| s | Gateway master secret |

| Identifier of sensor | |

| Long-term per-sensor secret | |

| Y | Gateway ephemeral ; X is user ephemeral |

| Z | ECDH secret ; |

| Per-sensor session key | |

| Pseudonym | |

| to deliver | |

| TS, ctr | Timestamp and per-session counter |

| SHA–256 hash and HKDF (extract&expand) | |

| AEAD | AES–GCM or ChaCha20–Poly1305 |

| Label | Definition |

|---|---|

| Z | (ECDH secret) |

| AD fields | Identities, subset tag, , , transcript hash |

| Scheme | Sensor Work (per ) | Gateway Work (per Run) | Bytes-on-Air (Control Plane) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3: Broadcast auth only | MAC verify (+buffering) | MAC generation (+key schedule) | broadcast (plus disclosure metadata); no ACKs | Authenticity only; no Key Agreement; no per-sensor session keys |

| B1: Shared broadcast | AEAD_open (+optional HKDF) | AEAD_enc | Broadcast ; ACKs optional | All receivers share the same ; limited sensor-to-sensor isolation |

| B2: LKH subset rekey (shared ) | AEAD_open; state | AEAD_enc | Broadcast ; ACKs optional | Efficient subset distribution; delivered key still shared across the addressed subset |

| LOTUS-AKA | HMAC (pseudonym) + AEAD_open + HKDF + HMAC (confirm) | ECC_mult + (HMAC + AEAD_enc + HMAC) | Broadcast ; ACKs | Perfect Forward Secrecy on U–G; per-sensor key isolation; sensors run symmetric-only |

| Party | Operations |

|---|---|

| User U | (public key, DH shared secret); HKDF: 1 extract expand; per-j: HKDF-expand (verify ). |

| Gateway G | ; PAKE verify; cookie MAC; per-j: (pseudonym ) (confirm). |

| Sensor | (confirm). |

| Term | Size (bytes) |

|---|---|

| Y (ephemeral pub. key) | (e.g., 32 for X25519). |

| (e.g., ). | |

| Per-sensor | (e.g., 16 truncated HMAC). |

| Per-sensor | (e.g., ). |

| Total Broadcast | |

| Total Acks | (e.g., headers). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

El Ghor, H.; El Fawal, A.H.; Mansour, A.; Ahmad-Kassem, A.; Nasser, A. Lightweight One-to-Many User-to-Sensors Authentication and Key Agreement. Information 2026, 17, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010047

El Ghor H, El Fawal AH, Mansour A, Ahmad-Kassem A, Nasser A. Lightweight One-to-Many User-to-Sensors Authentication and Key Agreement. Information. 2026; 17(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Ghor, Hussein, Ahmad Hani El Fawal, Ali Mansour, Ahmad Ahmad-Kassem, and Abbass Nasser. 2026. "Lightweight One-to-Many User-to-Sensors Authentication and Key Agreement" Information 17, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010047

APA StyleEl Ghor, H., El Fawal, A. H., Mansour, A., Ahmad-Kassem, A., & Nasser, A. (2026). Lightweight One-to-Many User-to-Sensors Authentication and Key Agreement. Information, 17(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010047