1. Introduction

Digital pathology has moved from glass slides to whole-slide images that capture tissue at very high resolution. This shift has opened a path for computational support in diagnosis and research, yet it also brings practical obstacles. Whole-slide images are too large for direct processing with conventional convolutional networks, and the lack of pixel-level labels makes fully supervised learning impractical at scale [

1,

2]. Multiple-instance learning has therefore become a natural choice. In this setting a slide is divided into many small patches that form a bag, and supervision is provided only at the bag level [

3]. Attention-based multiple-instance learning has helped identify which patches are most informative, but most methods still treat patches as independent and often rely on heuristic selection, which can discard subtle but clinically important regions [

4,

5]. These choices limit both accuracy and the coherence of heatmaps used for interpretation [

6,

7].

The clinical motivation is clear. Reliable slide-level classifiers can support triage, reduce variability among readers, and focus attention on suspicious regions. Studies in prostate biopsy grading already show that assistance from artificial intelligence can improve agreement with subspecialists and streamline review [

8,

9]. At the same time, weak supervision and strong inter-center variability make generalization difficult. Differences in staining, scanners, and patient populations amplify the risk of overfitting [

10,

11]. Methods that acknowledge spatial context while remaining trainable at whole-slide scale are still needed.

Multi-Instance Reinforcement Contrastive Learning, or MuRCL, moves the field forward by coupling reinforcement learning for patch selection with contrastive learning for representation learning [

12]. MuRCL improves how informative regions are chosen, yet it does not explicitly encode spatial relationships among patches and it does not regularize attention to produce smoother and more clinically faithful heatmaps. We explore these two gaps.

In practical terms, MuRCL can still attend to isolated patches that are individually discriminative but spatially incoherent, and it cannot enforce that neighbouring regions with similar morphology receive similar importance. Moreover, the CNN backbone used in MuRCL is agnostic to the explicit topology of the slide and operates on patches as independent inputs. SG-MuRCL was therefore designed to address these limitations by (i) inserting a graph neural network between the frozen CNN encoder and the MIL aggregator to propagate information across spatial neighbours, and (ii) adding an attention-smoothing operator to explicitly penalize fragmented, noisy attention patterns at the slide level.

Our study asks a single question: can explicit spatial modeling with graph neural networks and attention smoothing, when integrated into MuRCL, improve accuracy, robustness, and localization quality on whole-slide images without unacceptable computational cost?

We make three contributions. First, we reproduce MuRCL on CAMELYON16 and report a transparent baseline that others can compare against. Second, we design SG MuRCL, which combines a graph attention encoder to model spatial relations with a smoothed transformer-based attention-pooling module, while keeping the reinforcement learning selector and contrastive objective. Third, through systematic experiments we find that this integrated design exposes severe training instabilities that lead to collapse, and we analyze why this happens in practice. The result is a clear account of what works, what fails, and what the community may need to solve before complex spatial and selection mechanisms can be safely deployed at whole-slide scale.

6. Conclusions

This work set out to address a central limitation in computational pathology. Multiple-instance learning has become a practical choice for whole-slide image analysis, yet most approaches still struggle to capture the rich spatial context of tissue and often produce attention maps that are fragmented and difficult to interpret. We proposed SG_MuRCL as a direct response. The framework augments MuRCL with a graph neural network to model neighborhood structure and a smoothing operator to encourage coherent attention, with the goal of improving both accuracy and clinical interpretability.

We built a complete experimental pipeline that included offline patch extraction and graph construction, self-supervised pretraining with a contrastive objective, and supervised fine-tuning for slide-level classification. As a reference point we implemented the original MuRCL and obtained stable and reproducible results on CAMELYON16. When we integrated graphs and smoothing into the same training loop, the system did not converge. Across encoders the model collapsed to a trivial majority prediction, with area under the curve close to chance and a null F1 score. This negative result is the core empirical finding of the study.

The outcome carries an important message for the field. Combining several powerful modules that each work in isolation can introduce severe fragility when trained together. Large slide graphs increase memory use and force small batches, which amplifies gradient noise. The shared optimization of the graph encoder, the attention-based aggregator, and the reinforcement learner creates long and delicate gradient paths. In practice these factors can dominate any theoretical benefit and prevent learning altogether. For applied settings this suggests that reliability and computational cost remain first order concerns that must be considered alongside accuracy.

Several limitations qualify our conclusions. We used one primary dataset and did not apply stain normalization, which may affect generalization. The exact SimCLR weights cited in related work were not available, which can influence downstream performance. Resource constraints limited extensive ablations, and the tight coupling of components made it impossible to isolate a single point of failure with certainty.

The findings point to concrete next steps. Future work should explore hierarchical or sparse graph formulations that match the scale of whole-slide images while reducing memory pressure. Curriculum style or staged training that first stabilizes each module and only then couples them may improve optimization. Gradient accumulation and careful normalization can provide steadier updates at practical batch sizes. Reward shaping that ties the agent to uncertainty reduction or calibrated confidence may yield a more informative learning signal. Stronger regularization, stain normalization, and cross-cohort evaluation should be standard, and interpretability tools for graphs can test whether locality is truly being used when training succeeds.

In sum, we did not produce a new state-of-the-art system. Instead, we deliver a clear empirical boundary for current practice and a roadmap for progress. By prioritizing robustness, scalability, and transparent training procedures, the community can turn the promise of spatially aware multiple-instance learning into dependable tools for pathology and patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.M.Z.; methodology, B.Y.L. and S.S.M.Z.; software, B.Y.L.; validation, B.Y.L., S.S.M.Z., and Y.N.A.H.; formal analysis, B.Y.L.; investigation, B.Y.L.; resources, S.S.M.Z. and A.M.M.A.; data curation, B.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.S.M.Z., Y.N.A.H., and A.M.M.A.; visualization, B.Y.L.; supervision, S.S.M.Z. and Y.N.A.H.; project administration, S.S.M.Z.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All experiments used the publicly available CAMELYON16 dataset [

29]. The whole-slide images and slide-level labels can be obtained from the CAMELYON16 challenge website (access requires standard registration). No new human data were collected or generated for this study. Pre-processing scripts (tiling, tissue filtering, feature extraction/graph construction) and trained model checkpoints are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gadermayr, M.; Tschuchnig, M. Multiple instance learning for digital pathology: A review of the state-of-the-art, limitations and future potential. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2024, 112, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Ehteshami Bejnordi, B.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sanchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, M.A.; Cheplygina, V.; Granger, E.; Gagnon, G. Multiple instance learning: A survey of problem characteristics and applications. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilse, M.; Tomczak, J.M.; Welling, M. Attention-based deep multiple instance learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, T.; Jiang, K.; Yao, H. Dynamic policy-driven adaptive multiple instance learning for whole slide image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Macias, F.M.; Morales-Alvarez, P.; Wu, Y.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Sm: Enhanced localization in Multiple Instance Learning for medical imaging classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.03276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Verdelho, M.R.; Barata, C.; Santiago, C. The role of graph-based MIL and interventional training in the generalization of WSI classifiers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.19048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulten, W.; Balkenhol, M.; Awoumou Belinga, J.J.; Brilhante, A.; Cakir, A.; Farre, X.; Geronatsiou, K.; Molinie, V.; Pereira, G.; Roy, P.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Assistance Significantly Improves Gleason Grading of Prostate Biopsies by Pathologists. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.04500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, D.F.; Nagpal, K.; Sayres, R.; Foote, D.J.; Wedin, B.D.; Pearce, A.; Cai, C.J.; Winter, S.R.; Symonds, M.; Mermel, C.H.; et al. Evaluation of the Use of Combined Artificial Intelligence and Pathologist Assessment to Review and Grade Prostate Biopsies. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2023267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.Y.; Chen, R.J.; Wang, J.; Dillon, D.; Mahmood, F. Semi-supervised histology classification using deep multiple instance learning and contrastive predictive coding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, O.; Camara, A.; Moindrot, O.; de Lavergne, A.; Courtiol, P. Self-supervision closes the gap between weak and strong supervision in histology. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.03583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yu, L.; Wu, W.; Yu, R.; Zhang, D. MuRCL: Multi-instance reinforcement contrastive learning for whole slide image classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 47, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.H.; Jaume, G.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Lu, M.Y.; Vaidya, A.; Miller, T.R.; Mahmood, F. Artificial intelligence for digital and computational pathology. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2401.06148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mao, Y.; Guan, N.; Xue, C.J. Advances in multiple instance learning for whole slide image analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.09476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kuang, H.; Liu, J.; Yue, H.; He, M.; Wang, J. MiCo: Multiple instance learning with context-aware clustering for whole slide image analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.18028. [Google Scholar]

- Cersovsky, J.; Mohammadi, S.; Kainmueller, D.; Hoehne, J. Towards hierarchical regional transformer-based multiple instance learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Qiu, Y.; Nearchou, I.P.; Prost, S.; Fallowfield, J.A.; Bilen, H.; Kendall, T.J. Multiple instance learning with coarse-to-fine self-distillation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.02707. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Bian, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. TransMIL: Transformer-based correlated multiple instance learning for whole slide image classification. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fourkioti, O.; De Vries, M.; Jin, C.; Alexander, D.C.; Bakal, C. CAMIL: Context-aware multiple instance learning for cancer detection and subtyping in whole slide images. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Weng, W.H.; Chen, T.Y. Multimodal co-attention transformer for survival prediction in gigapixel whole slide images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.J.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.Y. Scaling vision transformers to gigapixel images via hierarchical self-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Li, Y.; Eliceiri, K.W. Dual-stream multiple instance learning network for whole slide image classification with self-supervised contrastive learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, T.; Lv, S.; Gao, Z.; Li, H. A weakly supervised multiple instance learning based on graph neural network for breast cancer pathology image classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communications, Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Hangzhou, China, 26–28 May 2023; pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Ye, D.; Cao, J.; Han, X.; Fu, Q.; Yang, W. RLogist: Fast observation strategy on whole-slide images with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.01737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, D.A.; Akhir, E.A.P.; Osman, N.A. Optimization techniques in reinforcement learning for healthcare: A review. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA), Pune, India, 23–24 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lakeman, S.; Mohammadi Ziabari, S.; Alsahag, A. A reinforcement-driven multiple instance learning framework for multi-task speaker attribute prediction. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.05709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehteshami Bejnordi, B.; Veta, M.; Van Diest, P.J.; van Ginneken, B.; Karssemeijer, N.; Litjens, G.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; CAMELYON16 Consortium. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA 2017, 38, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.Y.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Chen, T.Y.; Chen, R.J.; Barbieri, M.; Mahmood, F. Data efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole slide images. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.09666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakman, N.; Mohammadi Ziabari, S.; Alsahag, A.; Al Husaini, Y. Improving Accuracy and Interpretability in Reinforcement Learning-based Multiple Instance Learning. arXiv 2026, arXiv:submit/6965889. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Meng, X.; Zhou, J.; Ji, Y. High-risk factor prediction in lung cancer using thin CT scans: An attention-enhanced graph convolutional network approach. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.14000. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Kurz, G.; Polomac, N.; Gacheva, I.; Hattingen, E.; Triesch, J. Multiple instance learning for brain tumor detection from magnetic resonance spectroscopy data. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.08845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

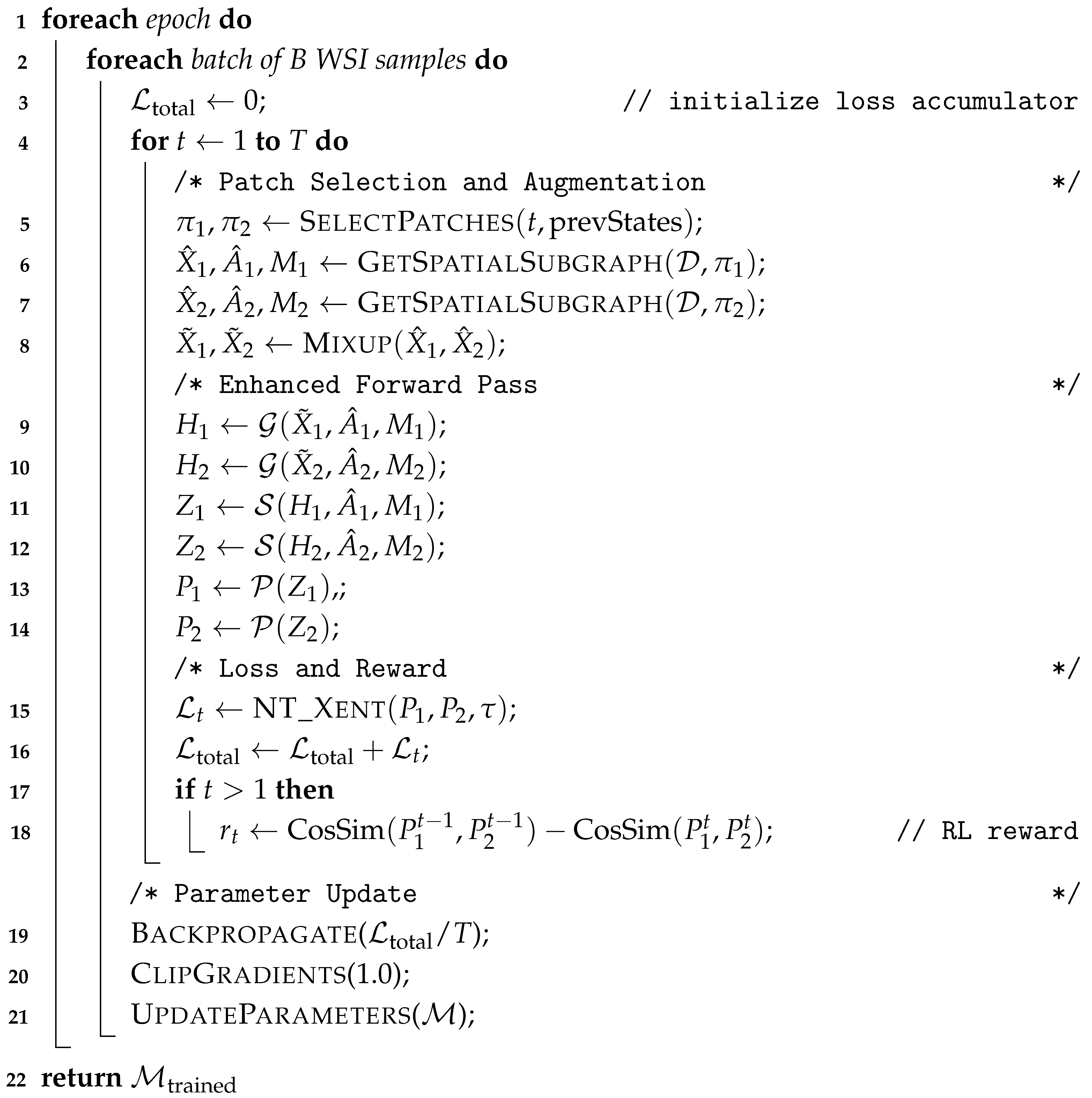

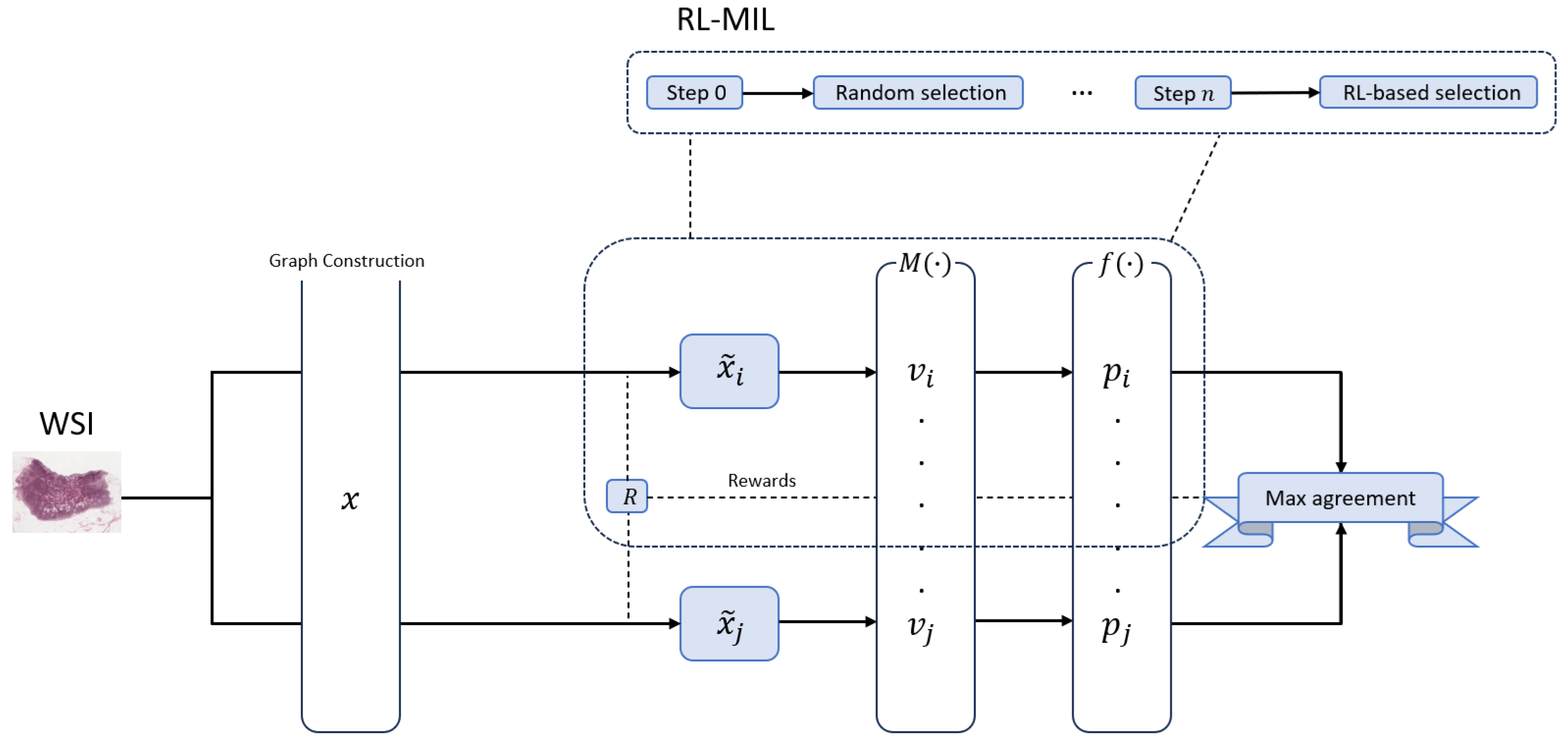

Figure 1.

High-level overview of the SG-MuRCL framework. A WSI is first converted into a patch-level graph x by a graph construction module. An RL agent R then draws two stochastic views of that graph, (top branch) and (bottom branch). Each view is passed through a shared GNN-MIL pipeline: a MIL aggregator pools node features into an embedding v, and a projection head converts v into the prediction vector p. The predictions and are compared in the Max-agreement block, which both supplies the contrastive loss for training and produces the scalar reward returned to the RL agent (dashed arrows). The dashed inset (top right) illustrates the agent’s policy over time: Step 0 samples a sub-graph at random; from Step 1 onward the agent follows a learned policy updated at every iteration with the reward produced by the Max-agreement module. This reward-guided sampling steers the agent toward the most discriminative patches while keeping the two branches synchronized through shared weights and a common reward signal.

![Information 17 00037 g001 Information 17 00037 g001]()

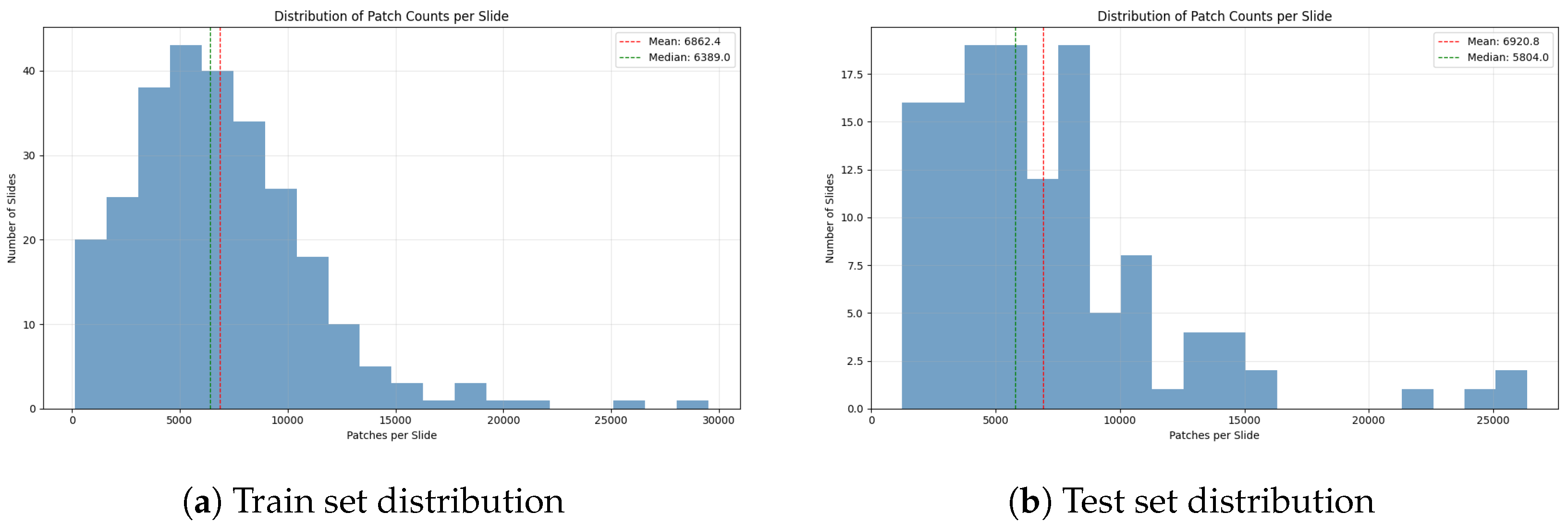

Figure 2.

High-level overview of SmTAP. Here, and denote instances, and are their corresponding feature embeddings, and and are the attention values assigned to each instance.

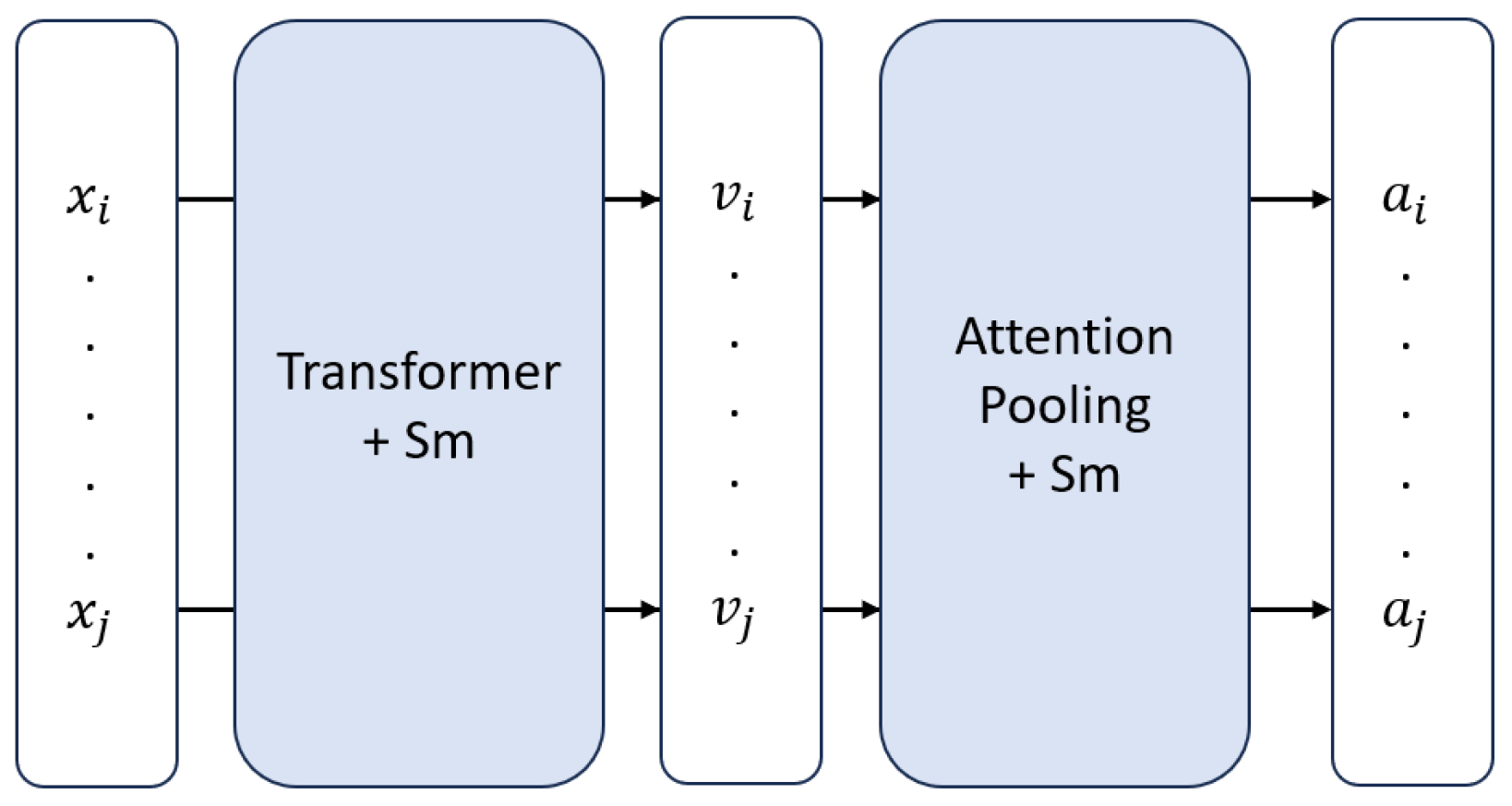

Figure 3.

Patch size distribution in the training and test sets of the CAMELYON16 dataset.

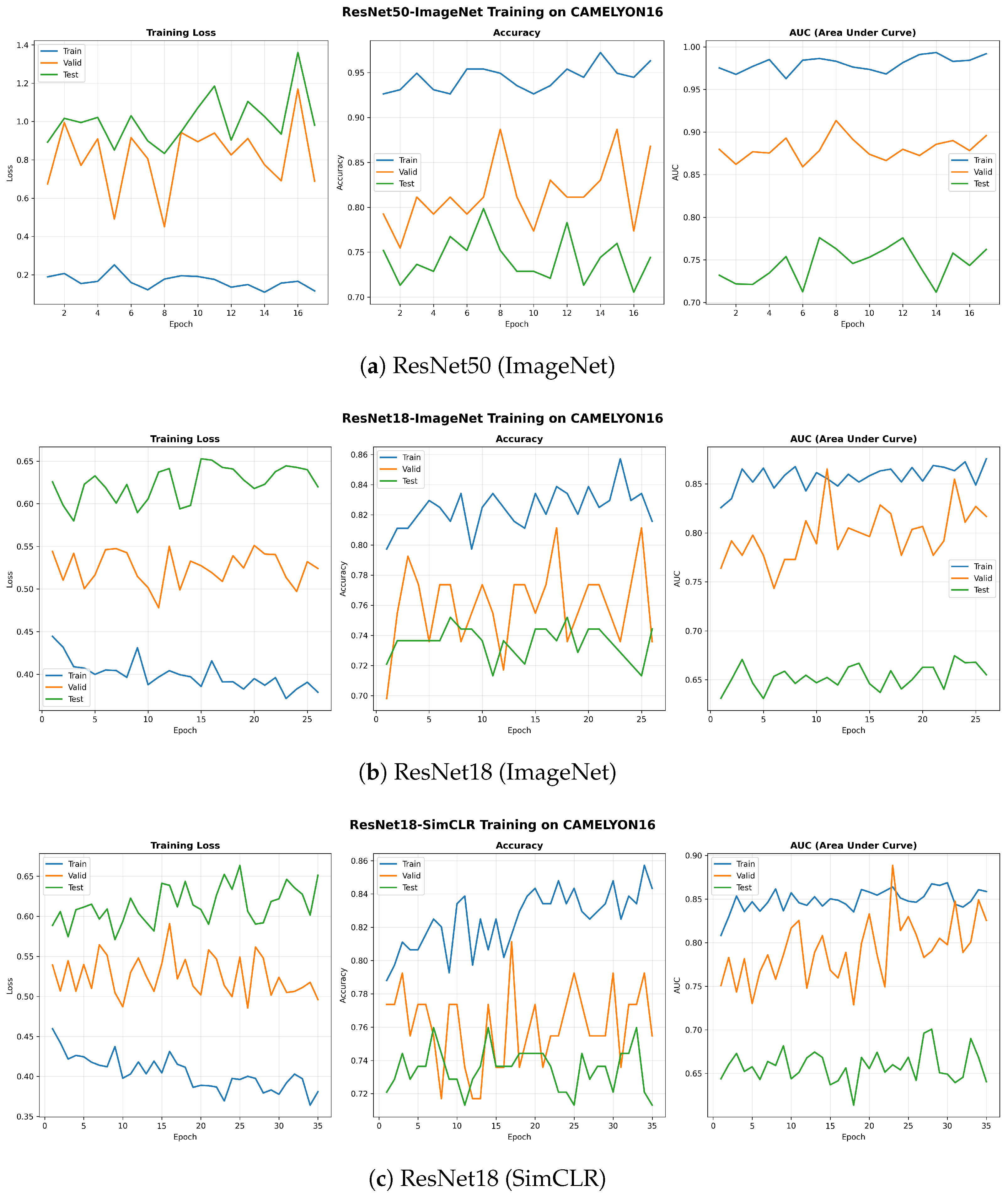

Figure 4.

Learning curves for the three MuRCL baseline configurations on the CAMELYON16 dataset. Each panel shows the training dynamics for its respective backbone.

Figure 5.

Intended effect of SmTAP on MuRCL.

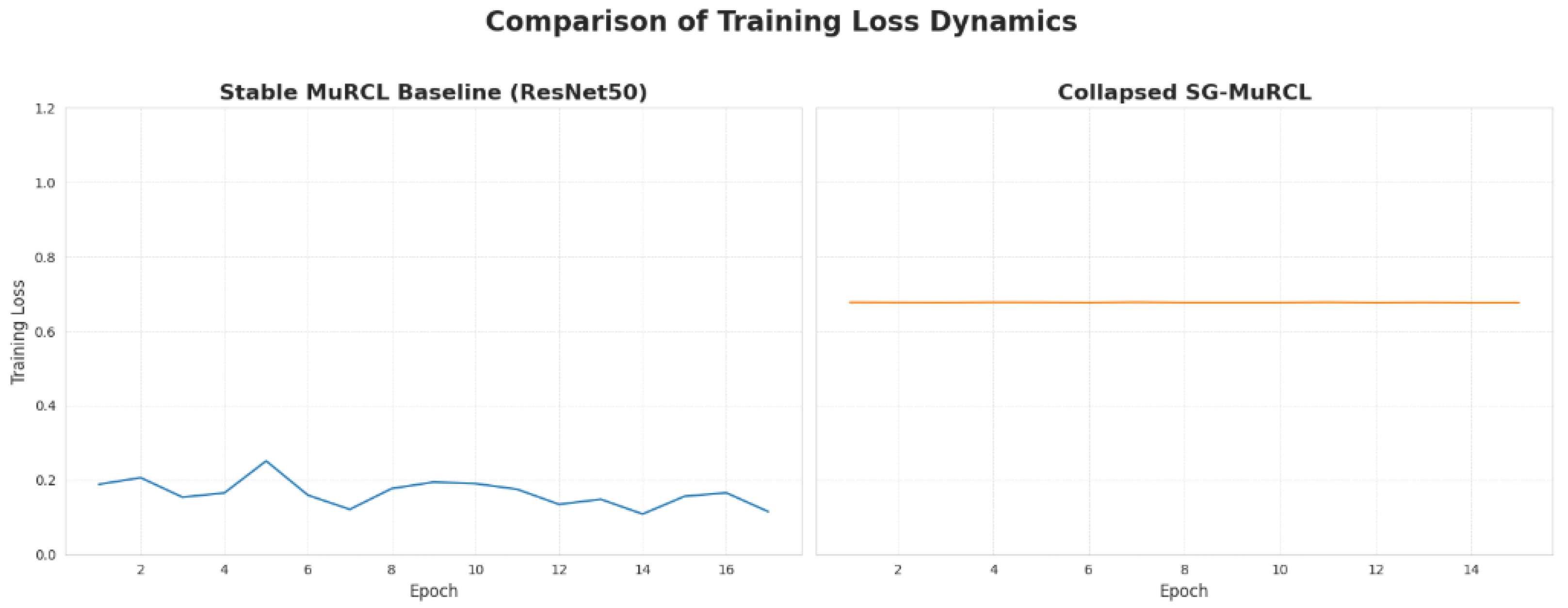

Figure 6.

Side-by-side comparison of training loss progression for the stable baseline and the collapsed SG-MuRCL.

Table 1.

Baseline performance of our MuRCL implementation on the CAMELYON16 test set. The best result in each metric column is highlighted in bold.

| Encoder | Loss | Acc. | AUC | Prec. | Recall | F1 |

|---|

| ResNet18 (ImageNet) | 0.645 | 0.744 | 0.652 | 0.750 | 0.490 | 0.593 |

| ResNet18 (SimCLR) | 0.682 | 0.674 | 0.658 | 0.600 | 0.429 | 0.500 |

| ResNet50 (ImageNet) | 0.882 | 0.752 | 0.754 | 0.748 | 0.510 | 0.610 |

Table 2.

Performance of the proposed SG-MuRCL framework on the CAMELYON16 test set for ResNet18, ResNet50 and ResNet18-SimCLR.

| Encoder | Loss | Acc. | AUC | Prec. | Recall | F1 |

|---|

| SG-MuRCL | 0.912 | 0.620 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Table 3.

Comparison of training loss variance, providing a quantitative measure of stability. A higher variance indicates a successful learning trajectory (decreasing loss), while a very low variance indicates a training collapse into a static, high-loss state.

| Model Configuration | Training Loss Variance |

|---|

| MuRCL (Stable Baseline) | 0.001279 |

| SG-MuRCL (Collapsed) | 0.000000 |

Table 4.

Ablation study: baseline MuRCL vs. MuRCL+SmTAP on the CAMELYON16 test set.

| Model | Acc. | AUC | Prec. | Recall | F1 |

|---|

| MuRCL (ResNet50, ImageNet) | 0.752 | 0.754 | 0.748 | 0.510 | 0.610 |

| MuRCL+SmTAP (ResNet50, ImageNet) | 0.761 | 0.768 | 0.755 | 0.528 | 0.622 |

Table 5.

Sensitivity to instance selection size k (with ).

| k (Instances) | Val. Acc. | Val. AUC | Val. F1 |

|---|

| 256 | 0.742 | 0.741 | 0.598 |

| 512 | 0.761 | 0.768 | 0.622 |

| 1024 | 0.758 | 0.771 | 0.619 |

Table 6.

Sensitivity to number of clusters K (with ).

| K (Clusters) | Val. Acc. | Val. AUC | Val. F1 |

|---|

| 5 | 0.748 | 0.759 | 0.607 |

| 10 | 0.761 | 0.768 | 0.622 |

| 20 | 0.755 | 0.764 | 0.615 |

Table 7.

Comparison of estimated average model forward pass latency per WSI.

| Model Configuration | Avg. Inference Time (sec/WSI) |

|---|

| MuRCL (Baseline) | ~1.1 |

| SG-MuRCL (Full) | ~3.2 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |