RFSCMOEA: A Dual-Population Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm with Relaxed Feasibility Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A novel environmental selection strategy combining relaxed feasibility selection with dual-criterion sorting is proposed to simultaneously enhance the feasibility, convergence, and diversity of the solution set. This model first constructs a relaxed feasibility threshold that dynamically shrinks during evolution, effectively retaining “near-feasible” solutions by quantifying constraint violations to help the population traverse infeasible barriers. Meanwhile, by integrating non-dominated sorting with a k-nearest neighbor density estimation mechanism, it prioritizes the retention of individuals in sparse regions—ensuring global convergence trends while preventing premature convergence—thereby establishing an adaptive balance between exploration and exploitation along complex constraint boundaries.

- A dynamic resource allocation mechanism based on shrinking contribution is designed to address the computational configuration challenges in cooperative evolution. By measuring the Euclidean distance shift between parent and offspring populations in the objective space, this mechanism quantifies the effective evolutionary contribution of populations in real-time (where a smaller shift indicates higher potential convergence value). Based on this evaluation coefficient, the algorithm dynamically adjusts the offspring generation ratio, automatically tilting computational resources toward the population demonstrating superior evolutionary performance, thus significantly reducing ineffective resource consumption while guaranteeing search quality.

- Comprehensive experiments involving 47 benchmark functions and 12 real-world engineering problems compare the proposed method against seven state-of-the-art CMOEAs. The results demonstrate that RFSCMOEA achieves the most balanced and superior performance across key metrics.

2. Related Work

2.1. Constatin Multi-Objective Optimization Problems

2.2. Approaches for Stepwise Approximation of the CPF

2.3. Multi-Stage Optimization Methods

2.4. Dual-Population Optimization Methods

3. Proposed Algorithm

3.1. Algorithm Framework

| Algorithm 1 The Evolutionary Process of RFSCMOEA |

|

| Algorithm 2 An Auxiliary Environment Selection Model Based on Feasibility-Relaxed Selection |

|

| Algorithm 3 Contractional Contribution-Based Dynamic Offspring Allocation |

|

3.2. Relaxed Feasibility Selection Model

3.3. Dynamic Resource Allocation Based on Shrinking Contribution

3.4. Evolutionary Operators

3.5. Complexity Analysis

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Comparative Algorithms and Parameters

4.2. Test Problems and Performance Metrics

5. Experimental Analysis

5.1. Comparison on CF Test Set

5.2. Comparison on DAS-CMOP Test Set

5.3. Comparison on LIR-CMOP Test Set

5.4. Comparison on MW Test Set

5.5. Comparison on RWMOP Test Set

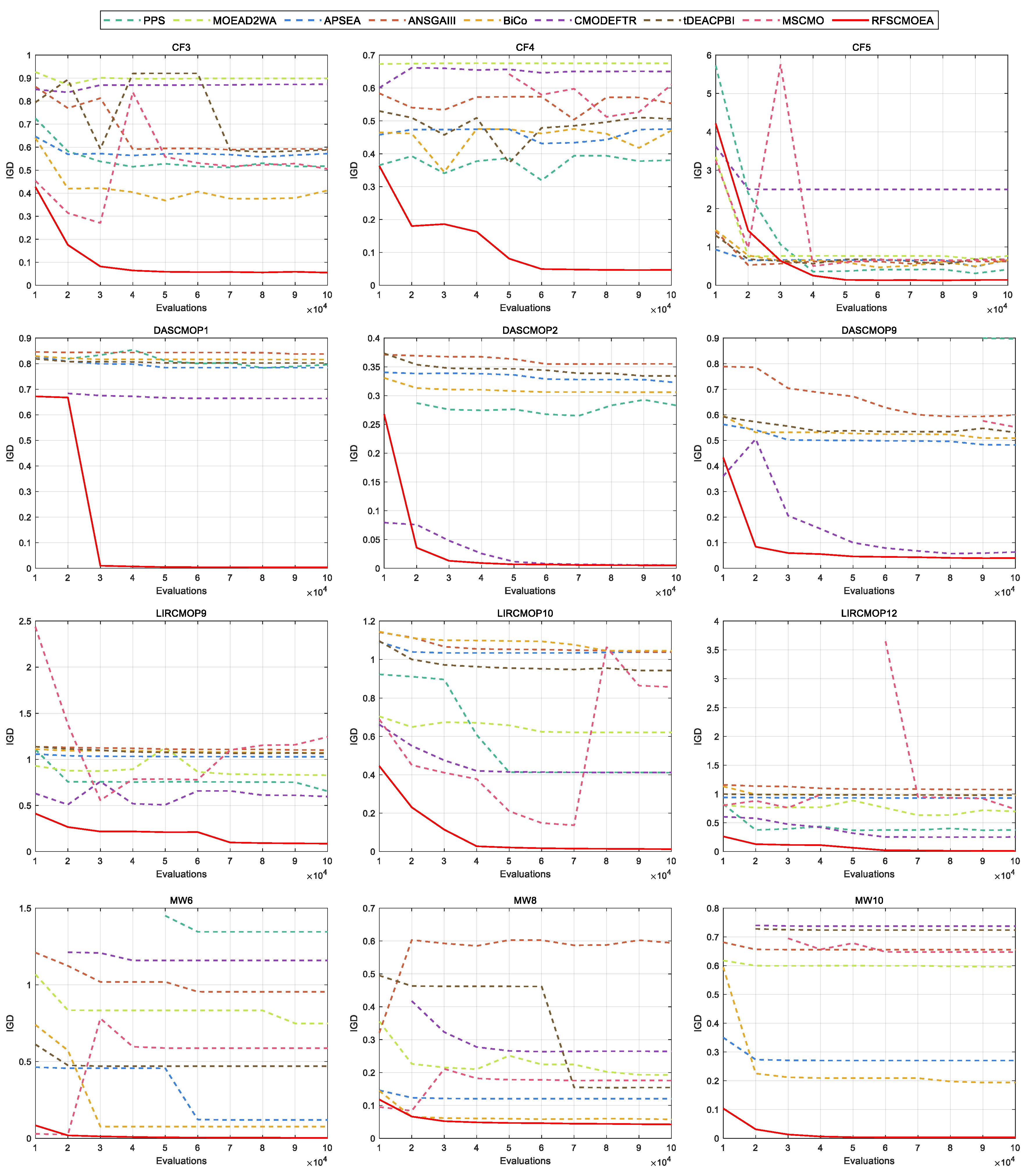

5.6. Convergence Behavior Analysis

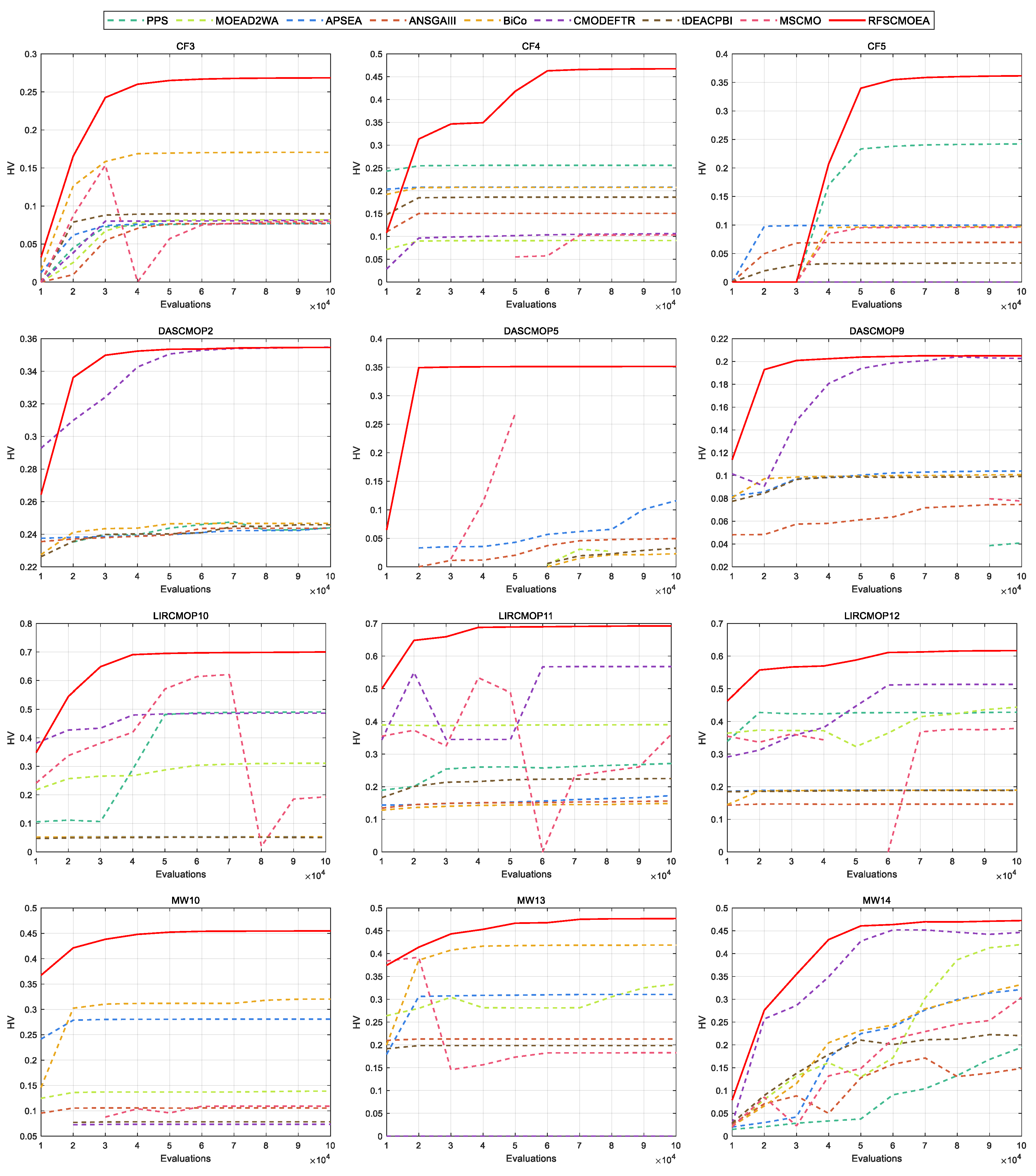

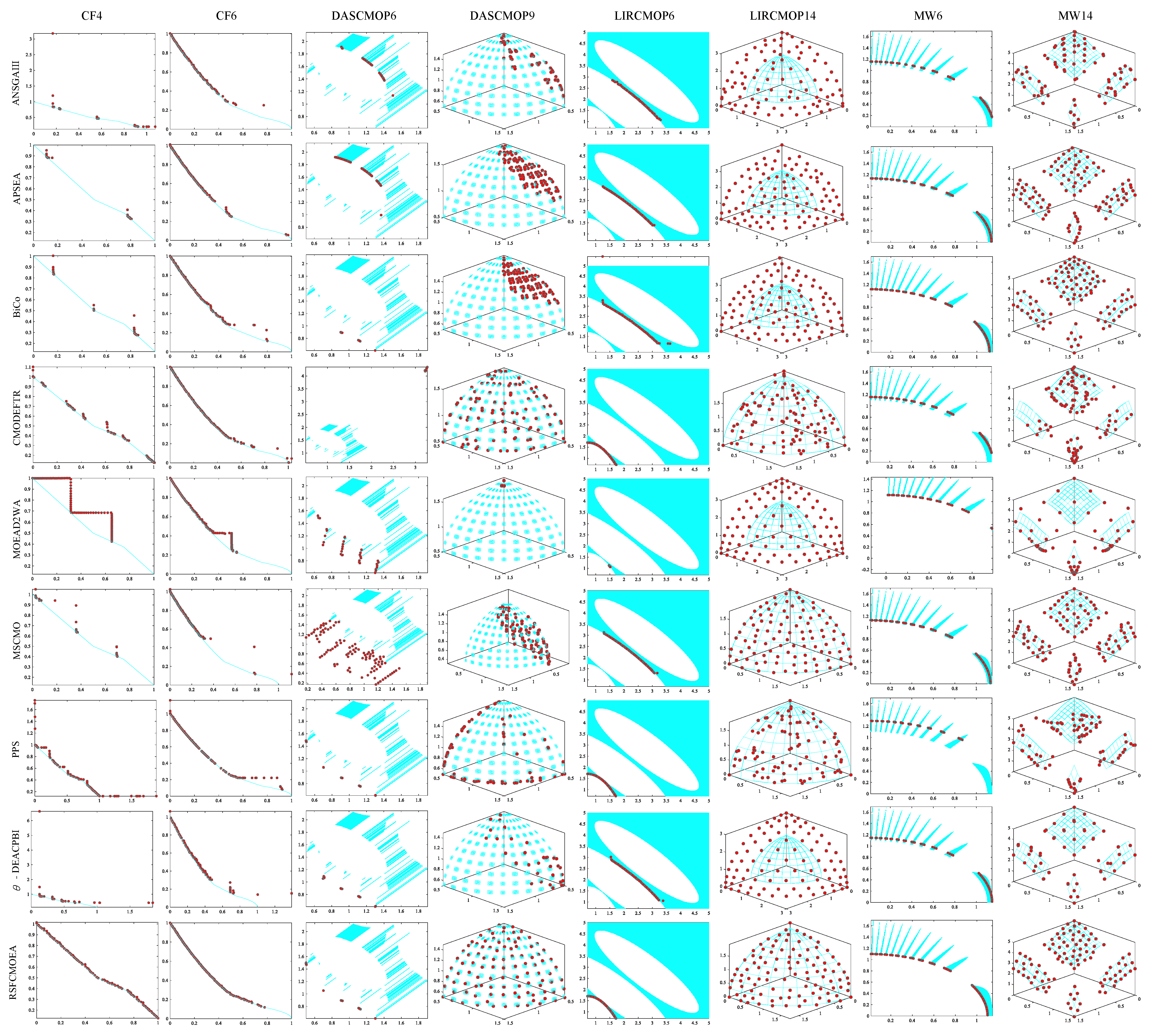

5.7. Diversity Analysis

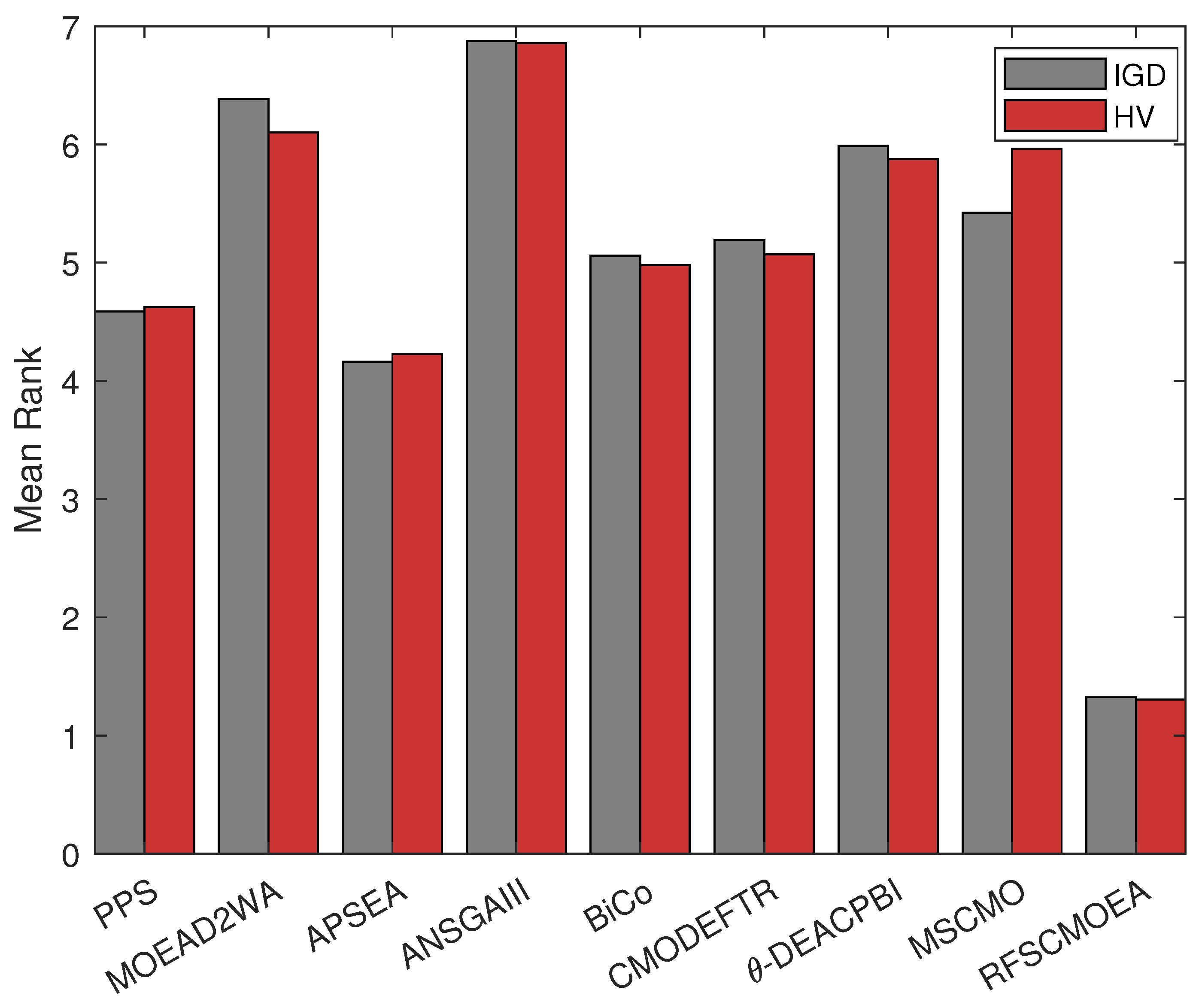

5.8. Statistical Analysis

5.9. Ablation Studies

5.10. Discussion of Performance Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, S.; Hao, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, T.; Li, X.; Liu, W. Two-stage bidirectional coevolutionary algorithm for constrained multi-objective optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 92, 101784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Schmitt, S.; Olhofer, M. An adaptive Bayesian approach to surrogate-assisted evolutionary multi-objective optimization. Inf. Sci. 2020, 519, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Peng, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Qin, K. Competition-based two-stage evolutionary algorithm for constrained multi-objective optimization. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 230, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Z.; Wang, Y. Handling Constrained Multiobjective Optimization Problems with Constraints in Both the Decision and Objective Spaces. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 23, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Yu, K.; Qu, B.; Liang, J.; Song, H.; Yue, C.; Lin, H.; Tan, K.C. Dynamic Auxiliary Task-Based Evolutionary Multitasking for Constrained Multiobjective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2023, 27, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Li, H.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Q.; Deb, K.; Goodman, E. Push and pull search for solving constrained multi-objective optimization problems. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2019, 44, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zou, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zheng, J. A Multistage Algorithm for Solving Multiobjective Optimization Problems with Multiconstraints. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2023, 27, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry-Straume, J.; Sarshar, A.; Popov, A.A.; Sandu, A. Physics-informed neural networks for PDE-constrained optimization and control. Commun. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Moni, A.; Yao, W.; Xu, M. Manifold Learning for Aerodynamic Shape Design Optimization. Aerospace 2025, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Shi, W.; Collu, M.; Venugopal, V.; Li, X. Multi-objective optimization design for a 15 MW semisubmersible floating offshore wind turbine using evolutionary algorithm. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Sun, J.; Gan, X.; Gong, D.; Wang, G.; Guo, Y. A Dynamic Interval Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm Based on Multi-Task Learning and Inverse Mapping. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2025, 29, 1619–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, X. Bi-goal evolution for many-objective optimization problems. Artif. Intell. 2015, 228, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Zeng, S.; Li, C.; Ong, Y.S. Two-type weight adjustments in MOEA/D for highly constrained many-objective optimization. Inf. Sci. 2021, 578, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Fang, Y.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Wei, C.; Goodman, E. MOEA/D with angle-based constrained dominance principle for constrained multi-objective optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 74, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.C. Indicator-Based Constrained Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 5414–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Suganthan, P.N. Localized Constrained-Domination Principle for Constrained Multiobjective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Song, W. A New Fitness Function With Two Rankings for Evolutionary Constrained Multiobjective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man-Cybern.-Syst. 2021, 51, 5005–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, Z. A Survey of Weight Vector Adjustment Methods for Decomposition-Based Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2020, 24, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, R. Adaptive multi-stage evolutionary search for constrained multi-objective optimization. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 7711–7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Shu, L.; Zhang, A. A Multi-Fidelity Bayesian Optimization Approach for Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization Problems. J. Mech. Des. 2024, 146, 071702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shen, B.; Pan, A. Constrained evolutionary optimization based on dynamic knowledge transfer. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 240, 122450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, Z.; Yen, G.G.; Zhang, L. Two-Stage Multiobjective Evolution Strategy for Constrained Multiobjective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2024, 28, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, F.; Gong, W.; Jin, Y. Even Search in a Promising Region for Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zou, J.; Tang, H.; Zheng, J.; Yu, F. Enhanced auxiliary population search for diversity improvement of constrained multiobjective coevolutionary optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 83, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Z. Two cooperative constraint handling techniques with an external archive for constrained multi-objective optimization. Memetic Comput. 2024, 16, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jia, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, Q. A Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm with a Population State Discrimination Model. Mathematics 2025, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, M.; Trivedi, A.; Wang, R.; Srinivasan, D.; Zhang, T. A dual-population-based evolutionary algorithm for constrained multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 25, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. A Coevolutionary Framework for Constrained Multiobjective Optimization Problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 25, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahama, T.; Sakai, S. Efficient constrained optimization by the ϵ constrained adaptive differential evolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–23 July 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, Y. A Pareto Front searching algorithm based on reinforcement learning for constrained multiobjective optimization. Inf. Sci. 2025, 705, 121985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Duan, L.; Liang, J.; Qiao, K.; Qu, B.; Sui, Q.; Ren, X. A cooperation and competition-based tri-population evolutionary algorithm for constrained multi-objective optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 183, 113658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, Y. Promising boundaries explore and resource allocation evolutionary algorithm for constrained multiobjective optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 92, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shen, B.; Pan, A.; Xue, J. Constraint landscape knowledge assisted constrained multiobjective optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 90, 101685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, X.; Gong, D.; He, J.; Fan, Z. Handling Multiobjective Optimization Problems With Complex Constraints: A Constraints Grouping-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 3866–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Liang, J.; Yu, K.; Yue, C.; Lin, H.; Zhang, D.; Qu, B. Evolutionary Constrained Multiobjective Optimization: Scalable High-Dimensional Constraint Benchmarks and Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2024, 28, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point-Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part I: Solving Problems With Box Constraints. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2014, 18, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Adaptive population sizing for multi-population based constrained multi-objective optimization. Neurocomputing 2025, 621, 129296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wei, H.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X. A multi-stage evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective optimization with complex constraints. Inf. Sci. 2021, 560, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Z. A constrained multiobjective differential evolution algorithm based on the fusion of two rankings. Inf. Sci. 2023, 647, 119572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, F.; Gong, W.; Wang, L.; Gao, L. A Constraint-Handling Technique for Decomposition-Based Constrained Many-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 7783–7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. PlatEMO: A MATLAB Platform for Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2017, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Y. Evolutionary Constrained Multiobjective Optimization: Test Suite Construction and Performance Comparisons. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 23, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, A.; Zhao, S.; Suganthan, P.; Liu, W.; Tiwari, S. Multiobjective optimization Test Instances for the CEC 2009 Special Session and Competition. Mech. Eng. 2008, 264, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Li, H.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Q.; Deb, K.; Goodman, E. Difficulty Adjustable and Scalable Constrained Multiobjective Test Problem Toolkit. Evol. Comput. 2020, 28, 339–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Huang, H.; Fang, Y.; You, Y.; Mo, J.; Wei, C.; Goodman, E. An improved epsilon constraint-handling method in MOEA/D for CMOPs with large infeasible regions. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 12491–12510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Wu, G.; Ali, M.Z.; Luo, Q.; Mallipeddi, R.; Suganthan, P.N.; Das, S. A Benchmark-Suite of real-World constrained multi-objective optimization problems and some baseline results. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 67, 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Huang, M.; Yang, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, X. An Adaptive Localized Decision Variable Analysis Approach to Large-Scale Multiobjective and Many-Objective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 6684–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: A comparative case study and the Strength Pareto approach. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1999, 3, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Tan, S.; Wang, H. A multi-objective differential evolutionary algorithm for constrained multi-objective optimization problems with low feasible ratio. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 80, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | Parameter Settings |

|---|---|

| PPS | = 1 , N = 300, |

| MOEAD2WA | = 4, = 5 |

| APSEA | = 0.01, = 0.05, F = 0.5 |

| ANSGAIII | |

| BiCo | = |

| CMODEFTR | , = 0.1 |

| -DEACPBI | = 1 − fr, , = 5 |

| MSCMO | = 0.01, g = 100 |

| Name | Problem | M | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| RWMOP1 | Pressure Vessel Design | 2 | 4 |

| RWMOP2 | Vibrating Platform Design | 2 | 5 |

| RWMOP3 | Two Bar Truss Design | 2 | 3 |

| RWMOP4 | Welded Beam Design | 2 | 4 |

| RWMOP5 | Speed Reducer Design | 2 | 7 |

| RWMOP6 | Gear Train Design | 2 | 4 |

| RWMOP7 | Car Side Impact Design | 3 | 7 |

| RWMOP8 | Simply Supported I-beam Design | 2 | 4 |

| RWMOP9 | Multiple Disk Clutch Brake Design | 2 | 5 |

| RWMOP10 | Spring Design | 2 | 3 |

| RWMOP11 | Cantilever Beam Design | 2 | 2 |

| RWMOP12 | Front Rail Design | 2 | 3 |

| PPS | MOEAD2WA | APSEA | ANSGAIII | BiCo | CMODEFTR | -DEACPBI | MSCMO | RFSCMOEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF1 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF2 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF4 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF5 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF6 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF8 | () + | NaN (93.33%) + | () + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | () + | () |

| CF9 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF10 | () − | NaN (73.33%) − | () − | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (48.23%) − | NaN (0.00%) |

| +/−/= | 8/2/0 | 9/1/0 | 9/1/0 | 9/0/1 | 9/0/1 | 9/0/1 | 9/0/1 | 9/1/0 | |

| DASCMOP1 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (67.43%) + | () |

| DASCMOP2 | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (87.20%) + | () |

| DASCMOP3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (83.53%) + | () |

| DASCMOP4 | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | () + | () + | () |

| DASCMOP5 | () + | () + | () = | NaN (73.33%) + | () + | NaN (3.33%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | () + | () |

| DASCMOP6 | () + | () + | () + | NaN (73.33%) + | () + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (87.30%) + | NaN (64.27%) + | () |

| DASCMOP7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (3.33%) + | () + | () + | () |

| DASCMOP8 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (3.33%) + | () + | () + | () |

| DASCMOP9 | () + | NaN (32.05%) + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| +/−/= | 8/0/1 | 9/0/0 | 7/1/1 | 9/0/0 | 9/0/0 | 8/1/0 | 9/0/0 | 9/0/0 | |

| LIRCMOP1 | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (83.33%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP2 | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (82.00%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (63.40%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP4 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (70.13%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP5 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP6 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () + | NaN (66.07%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP8 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () + | NaN (68.73%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP9 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP10 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP11 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP12 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP13 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP14 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () |

| +/−/= | 10/2/2 | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 9/2/3 | 14/0/0 | 13/1/0 | |

| MW1 | NaN (NaN%) + | NaN (26.67%) + | NaN (30.00%) + | NaN (3.33%) + | NaN (60.00%) + | NaN (20.00%) + | NaN (10.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | () |

| MW2 | NaN (NaN%) + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (83.33%) + | () + | () + | () |

| MW3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () + | () + | () |

| MW4 | () + | NaN (16.67%) + | NaN (40.00%) + | NaN (16.81%) + | NaN (30.00%) + | NaN (40.00%) + | NaN (33.33%) + | NaN (36.67%) + | () |

| MW5 | () + | NaN (36.67%) + | NaN (36.67%) + | NaN (26.70%) + | NaN (90.00%) + | NaN (10.00%) + | NaN (40.00%) + | NaN (27.17%) + | () |

| MW6 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| MW7 | () + | () + | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () |

| MW8 | NaN (NaN%) + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (73.33%) + | () + | () + | () |

| MW9 | () + | NaN (50.00%) + | NaN (70.00%) + | NaN (33.33%) + | NaN (83.33%) + | NaN (16.67%) + | NaN (36.67%) + | NaN (73.33%) + | () |

| MW10 | NaN (NaN%) + | () + | NaN (93.33%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | () + | NaN (13.33%) + | NaN (93.33%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | () |

| MW11 | () + | () + | () − | () + | () = | NaN (93.33%) + | () + | () = | () |

| MW12 | () + | NaN (60.43%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | NaN (43.33%) + | NaN (96.67%) + | NaN (43.33%) + | NaN (46.67%) + | NaN (63.37%) + | () |

| MW13 | 1.35 () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (96.67%) + | () + | () + | () |

| MW14 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| +/−/= | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 12/1/1 | 14/0/0 | 13/0/1 | 13/0/1 | 14/0/0 | 12/0/2 | |

| RWMOP1 | () + | () + | () + | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP2 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP4 | () − | () + | () + | () − | () + | () + | () = | () + | () |

| RWMOP5 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP6 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP8 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP9 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP10 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP11 | () = | () + | () = | () + | () = | () = | () + | () = | () |

| RWMOP12 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| +/−/= | 10/1/1 | 12/0/0 | 11/0/1 | 10/1/1 | 11/0/1 | 11/0/1 | 11/0/1 | 11/0/1 |

| PPS | MOEAD2WA | APSEA | ANSGAIII | BiCo | CMODEFTR | -DEACPBI | MSCMO | RFSCMOEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF1 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF2 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF4 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF5 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF6 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF8 | () + | NaN (93.33%) + | () + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | () + | () |

| CF9 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| CF10 | () − | NaN (73.33%) − | () − | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (0.00%) = | NaN (48.23%) − | NaN (0.00%) |

| +/−/= | 8/2/0 | 9/1/0 | 9/1/0 | 9/0/1 | 9/0/1 | 9/0/1 | 9/0/1 | 9/1/0 | |

| DASCMOP1 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (67.43%) + | () |

| DASCMOP2 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (87.20%) + | () |

| DASCMOP3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (83.53%) + | () |

| DASCMOP4 | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | () + | () + | () |

| DASCMOP5 | () + | () + | () = | NaN (73.33%) + | () + | NaN (3.33%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | () + | () |

| DASCMOP6 | () + | () + | () + | NaN (73.33%) + | () + | NaN (0.00%) + | NaN (87.30%) + | NaN (64.27%) + | () |

| DASCMOP7 | () + | () + | () − | () + | () + | NaN (3.33%) + | () − | () + | () |

| DASCMOP8 | () + | () + | () − | () + | () + | NaN (3.33%) + | () = | () + | () |

| DASCMOP9 | () + | NaN (32.05%) + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| +/−/= | 8/1/0 | 9/0/0 | 5/3/1 | 9/0/0 | 9/0/0 | 7/2/0 | 7/1/1 | 9/0/0 | |

| LIRCMOP1 | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (83.33%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP2 | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (82.00%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (63.40%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP4 | () = | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (70.13%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP5 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP6 | () − | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (66.07%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP8 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | NaN (68.73%) + | () |

| LIRCMOP9 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP10 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP11 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP12 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP13 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| LIRCMOP14 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () = | () |

| +/−/= | 9/2/3 | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 9/4/1 | 14/0/0 | 13/0/1 | |

| MW1 | NaN (NaN%) + | NaN (26.67%) + | NaN (30.00%) + | NaN (3.33%) + | NaN (60.00%) + | NaN (20.00%) + | NaN (10.00%) + | NaN (0.00%) + | () |

| MW2 | NaN (NaN%) + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (83.33%) + | () + | () + | () |

| MW3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () = | () + | () |

| MW4 | () + | NaN (16.67%) + | NaN (40.00%) + | NaN (16.81%) + | NaN (30.00%) + | NaN (40.00%) + | NaN (33.33%) + | NaN (36.67%) + | () |

| MW5 | () + | NaN (36.67%) + | NaN (36.67%) + | NaN (26.70%) + | NaN (90.00%) + | NaN (10.00%) + | NaN (40.00%) + | NaN (27.17%) + | () |

| MW6 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| MW7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | () + | () |

| MW8 | NaN (NaN%) + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (73.33%) + | () + | () + | () |

| MW9 | () + | NaN (50.00%) + | NaN (70.00%) + | NaN (33.33%) + | NaN (83.33%) + | NaN (16.67%) + | NaN (36.67%) + | NaN (73.33%) + | () |

| MW10 | NaN (NaN%) + | () + | NaN (93.33%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | () + | NaN (13.33%) + | NaN (93.33%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | () |

| MW11 | () + | () + | () − | () + | () − | NaN (93.33%) + | () + | () = | () |

| MW12 | () + | NaN (60.43%) + | NaN (86.67%) + | NaN (43.33%) + | NaN (96.67%) + | NaN (43.33%) + | NaN (46.67%) + | NaN (63.37%) + | () |

| MW13 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | NaN (96.67%) + | () + | () + | () |

| MW14 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| +/−/= | 14/0/0 | 14/0/0 | 13/1/0 | 14/0/0 | 13/1/0 | 12/2/0 | 13/0/1 | 13/0/1 | |

| RWMOP1 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP2 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP3 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP4 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP5 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP6 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | () |

| RWMOP7 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP8 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP9 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP10 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP11 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () |

| RWMOP12 | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () + | () − | () + | () |

| +/−/= | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 10/2/0 | 12/0/0 |

| RFSCMOEA vs. | p-Value | Significance () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPS | 1541 | 170 | 5.6799 | YES |

| MOEAD2WA | 1758 | 12 | 2.2651 | YES |

| APSEA | 1632 | 21 | 7.9861 | YES |

| ANSGAIII | 1645 | 66 | 5.0219 | YES |

| BiCo | 1542 | 54 | 6.6622 | YES |

| CMODEFTR | 1478 | 118 | 1.4889 | YES |

| -DEACPBI | 1613 | 40 | 2.1199 | YES |

| MSCMO | 1632 | 21 | 7.9861 | YES |

| RFSCMOEA vs. | p-Value | Significance () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPS | 1666 | 104 | 1.9176 | YES |

| MOEAD2WA | 1714 | 56 | 2.0068 | YES |

| APSEA | 1678 | 92 | 1.1362 | YES |

| ANSGAIII | 1711 | 0 | 1.7996 | YES |

| BiCo | 1705 | 6 | 2.4614 | YES |

| CMODEFTR | 1621 | 90 | 1.5816 | YES |

| -DEACPBI | 1684 | 27 | 7.2444 | YES |

| MSCMO | 1734 | 36 | 7.5452 | YES |

| CF | DASCMOP | LIRCMOP | MW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPS | 46.2195 | 31.2500 | 18.3614 | 15.4074 |

| MOEAD2WA | 41.5294 | 33.0780 | 18.0160 | 15.0826 |

| APSEA | 14.2972 | 19.9688 | 11.7372 | 11.7555 |

| ANSGAIII | 26.4303 | 84.9849 | 16.7336 | 11.0107 |

| BiCo | 27.7253 | 19.8886 | 10.1905 | 12.2064 |

| CMODEFTR | 17.8635 | 24.4330 | 9.1461 | 8.7298 |

| -DEACPBI | 26.0543 | 107.2495 | 12.7573 | 22.9835 |

| MSCMO | 13.5087 | 37.8827 | 47.6828 | 30.0722 |

| RFSCMOEA | 10.0185 | 13.7689 | 7.3672 | 8.0217 |

| Algorithm | Description |

|---|---|

| RFSCMOEA-A | Replaces the environmental selection of the auxiliary population with the -constraint model. |

| RFSCMOEA-B | Replaces the environmental selection of the auxiliary population with a strict separation of feasible and infeasible solutions (rather than weak-feasible). |

| RFSCMOEA-C | Replaces the environmental selection of the auxiliary population with the CDP model. |

| RFSCMOEA-D | Fixes the population sizes to a constant NP (removes dynamic resource allocation). |

| RFSCMOEA-E | Removes cross-population interaction: DE/current-to-best/1 selects only from , and DE/rand/1 selects only from . |

| RFSCMOEA-F | In this algorithm, HV is used to replace the shift distances (d) in Dynamic Resource Allocation Based on Shrinking Contribution. |

| RFSCMOEA vs. | IGD () | p-Value | HV () | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFSCMOEA-A | 40/5/2 | 0.000201 | 41/4/2 | 0.000164 |

| RFSCMOEA-B | 42/3/2 | 0.000015 | 43/2/2 | 0.000058 |

| RFSCMOEA-C | 43/2/2 | 0.000602 | 44/1/2 | 0.000389 |

| RFSCMOEA-D | 45/1/1 | 0.000137 | 46/0/1 | 0.000527 |

| RFSCMOEA-E | 44/2/1 | 0.000042 | 45/1/1 | 0.000001 |

| RFSCMOEA-F | 43/1/3 | 0.000021 | 44/1/2 | 0.000000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Jia, H.; Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, Q.; Chen, S. RFSCMOEA: A Dual-Population Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm with Relaxed Feasibility Selection. Information 2026, 17, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010036

Li Y, Jia H, Lin X, Li Y, Shi Q, Chen S. RFSCMOEA: A Dual-Population Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm with Relaxed Feasibility Selection. Information. 2026; 17(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yongchao, Heming Jia, Xinyan Lin, Yaqiao Li, Qian Shi, and Shiwei Chen. 2026. "RFSCMOEA: A Dual-Population Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm with Relaxed Feasibility Selection" Information 17, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010036

APA StyleLi, Y., Jia, H., Lin, X., Li, Y., Shi, Q., & Chen, S. (2026). RFSCMOEA: A Dual-Population Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm with Relaxed Feasibility Selection. Information, 17(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010036