1. Introduction

Entity Relationship Extraction (RE) is a fundamental task in Natural Language Processing (NLP), which aims to identify and extract entities (such as people, organizations, locations, and more) and the relationships between them from unstructured text. This task is crucial for a wide range of NLP applications, including intelligent question–answering (Q&A) systems, where understanding relationships between entities is key to providing accurate answers, knowledge graph construction, which organizes information in a structured form, and information retrieval, in turn helping systems understand and retrieve relevant documents [

1]. The ability to accurately identify entities and their relationships is critical to improving the quality and relevance of search results and system responses.

The growing volume of unstructured text data in the era of big data has amplified the challenges faced by RE systems. Traditional techniques, such as rule-based approaches and feature-engineered machine learning models, often struggle to generalize to large-scale and heterogeneous text data. These conventional methods also encounter difficulties when processing diverse and complex linguistic phenomena, including varied sentence structures, ambiguous expressions, and implicit relationships between entities. As text data continues to increase in scale and complexity, the limitations of these traditional methods become more apparent, highlighting the need for more robust and adaptable solutions in RE.

In recent years, deep learning techniques have brought significant advancements to the field of RE. The development of pre-trained language models such as RoBERTa, BERT, and ERNIE has substantially improved the ability to capture rich contextual representations of text [

2]. These models, trained on large-scale corpora, are capable of modeling nuanced semantic dependencies, making them highly effective for entity recognition and relation extraction. In addition, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) networks have been widely adopted to capture local and long-range dependencies in text. More recently, attention mechanisms and graph neural networks (GNNs) have been introduced to further enhance representation learning [

3]. Attention mechanisms allow models to selectively focus on informative tokens, while GNNs explicitly model interactions among entities, improving extraction performance in complex relational contexts [

4].

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. First, modeling complex contextual information and long-distance dependencies is still difficult, as relations may span multiple clauses or exhibit implicit semantic patterns. Second, existing models often lack robustness when salient relational cues are sparsely distributed or entangled with irrelevant contextual information, leading to suboptimal information utilization. Finally, many approaches show limited generalization beyond benchmark datasets, and their performance often degrades in real-world scenarios characterized by noisy, unstructured, or domain-specific text.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel multi-mechanism fusion model for entity–relation extraction. The proposed model integrates multiple complementary representation learning components to enhance robustness and adaptability across heterogeneous sentence structures. Rather than explicitly optimizing for hardware-level efficiency, our goal is to enable adaptive utilization of model capacity, allowing different inputs to activate different modeling components according to their structural and semantic complexity.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

Context-aware lexical encoding with whole-word masking. We employ a pre-trained Chinese RoBERTa-wwm-ext encoder with a whole-word masking strategy, which preserves semantic integrity in multi-character Chinese text and improves contextual representation quality.

Selective feature modeling via attention mechanisms. Multi-head attention and gated attention mechanisms are jointly incorporated to enhance salient semantic features and suppress less informative context, improving robustness in entity–relation extraction.

Input-adaptive dynamic network architecture. We introduce a dynamic framework that adaptively controls the execution of feature modeling modules based on input characteristics, enabling flexible and robust utilization of model capacity across simple and complex sentence structures.

3. Proposed Methods

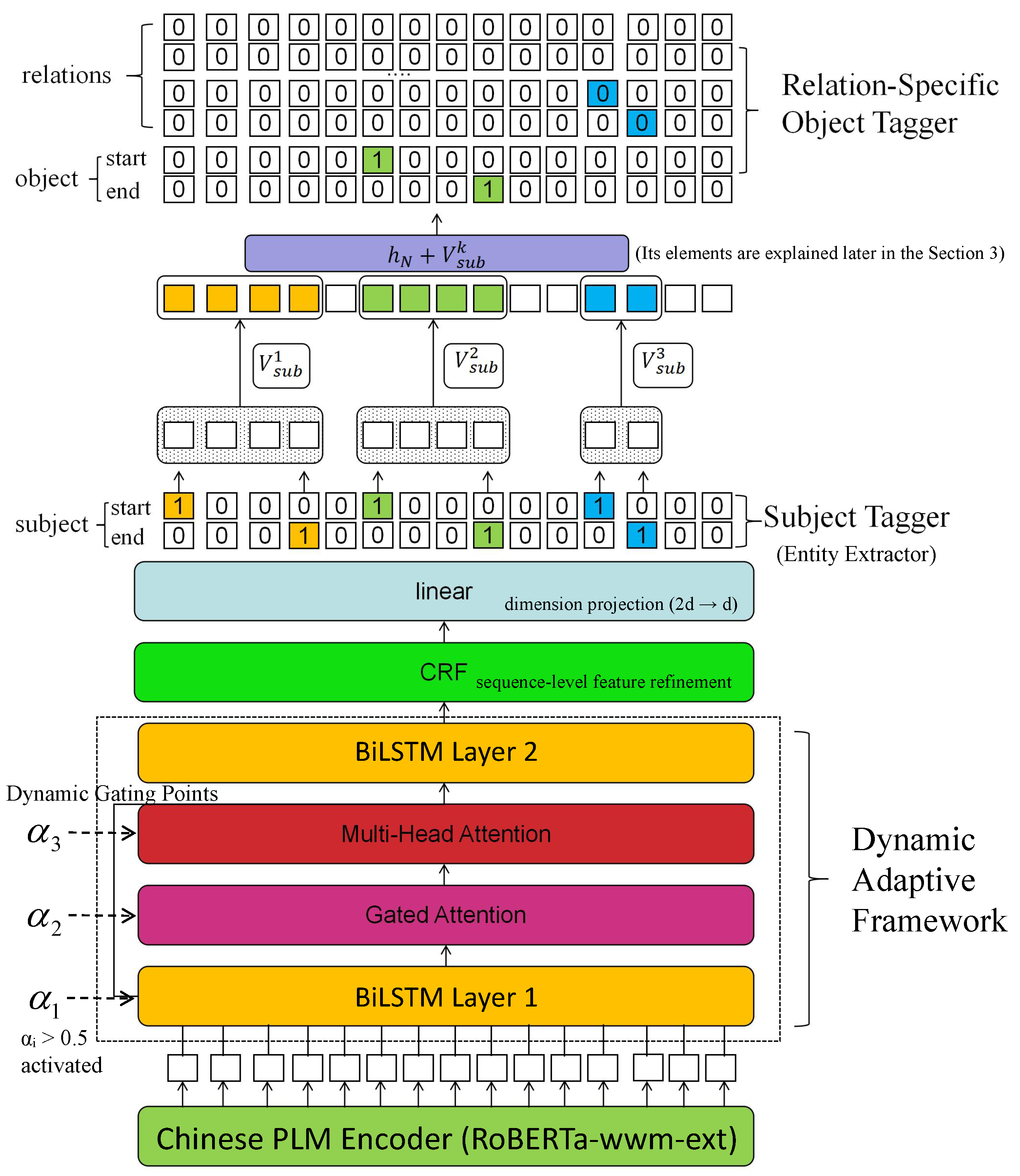

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed model. The model adopts Chinese-RoBERTa-wwm-ext as the underlying semantic encoder and introduces a dynamic adaptive framework between the encoding stage and the task-specific decoding stage. This framework dynamically controls the activation of multiple feature modeling modules, including two BiLSTM layers, a multi-head attention module, and a gated attention module, thereby enabling adaptive information flow and flexible network paths.

The proposed model consists of the following key components, corresponding to the elements shown in

Figure 1:

Chinese PLM Encoder (RoBERTa-wwm-ext): This module encodes the input sentence into contextualized token representations. The whole-word masking strategy is particularly suitable for Chinese multi-character words.

Dynamic Adaptive Framework: As shown in

Figure 1, this framework encompasses BiLSTM layer 1, multi-head attention, gated attention, and BiLSTM layer 2. A dynamic gating mechanism assigns activation scores

to each module, and modules with

are activated during forward propagation. This design allows the model to adaptively select computational paths based on input complexity, rather than executing all modules for every sentence.

BiLSTM Layer 1 and BiLSTM Layer 2: The first BiLSTM layer captures bidirectional sequential dependencies from encoder outputs. After attention-based feature enhancement, the second BiLSTM layer further refines local contextual information. These two layers are explicitly distinguished in

Figure 1 to avoid confusion.

Linear Layer: A linear layer is applied after BiLSTM processing to align feature dimensions and to project attention-enhanced representations into a unified latent space suitable for downstream entity and relation extraction.

CRF Layer: The CRF layer operates on the sequence-level feature representations to enhance global consistency. It serves as a feature refinement and regularization component rather than an independent decoding stream, and does not replace the CasRel-based span prediction mechanism.

Entity Extractor (Subject Tagger): This module corresponds to the subject tagger shown in

Figure 1. It consists of binary classifiers that predict the start and end positions of subject entities.

Joint Object–Relationship Extraction Module: Conditioned on detected subjects, relation-specific object taggers predict object spans independently for each relation type, enabling joint extraction of relational triples.

A significant obstacle in NLP is combined entity and relation extraction, which aims to concurrently recognize entities and their relations (subject s, relation r, and object o) from unstructured text. A major challenge in natural language processing is joint entity and relation extraction, which aims to simultaneously identify entities and their semantic relations in the form of subject–relation–object triples

from unstructured text. In this work, we adopt an enhanced CasRel-based framework [

4] to model this task through a conditional probabilistic factorization.

Following the CasRel paradigm, relational triples extraction is formulated as follows. Given an input sentence

x, the goal is to extract a set of relational triples

where

s and

o denote subject and object entity spans, respectively, and

denotes a predefined relation type.

The joint probability of all triples in a sentence is factorized as

where

denotes the set of detected subject entities, and

represents the subset of triples whose subject is

s.

Under this formulation, subject extraction is performed first by predicting the start and end positions of subject spans conditioned on the input sentence. For each detected subject s, object entities are then predicted independently for each relation type . For relation types that do not form a valid triple with subject s in the current sentence, a null object is implicitly assumed.

This factorization decouples subject detection from relation-conditioned object prediction, enabling the model to naturally handle overlapping triples and multiple relations per entity pair. Importantly, all relation types are evaluated independently rather than through mutual exclusion, which is a key advantage of the CasRel framework. During inference, the model first decodes subject spans from the refined token representations, and then predicts relation-conditioned object spans for each detected subject. The final relational triples are constructed by combining subject spans, relation types, and corresponding object spans.

3.2. Attention-Enhanced BiLSTM Module

The Attention-Enhanced BiLSTM module follows a sequential and dynamically controlled pipeline. It first applies a BiLSTM layer to the contextual embeddings to capture bidirectional dependencies. The output is projected back to dimension d and subsequently processed by a multi-head self-attention layer to model global token interactions. A gated attention mechanism is then applied to generate feature-wise importance weights, which are used to modulate the original representations through element-wise multiplication. Finally, the fused features are passed to downstream extraction modules.

By recognizing the bidirectional relationships between phrases and producing contextual representations of superior quality, BiLSTM offers a strong basis for the relational extraction job. The first BiLSTM processes each word in the phrase step-by-step and constructs the corresponding contextual representation, using as input the word embeddings produced by the pre-trained language model Chinese-RoBERTa-wwm-ext. The output is represented by Equation (6):

To improve the accuracy of entity-relationship extraction, the model integrates gated and multi-head attention mechanisms, allowing it to dynamically adjust attention weights based on contextual information. Not every word in a sentence contributes equally to identifying entities and relationships, so an adaptive mechanism is necessary to highlight the most informative terms.

The gated attention layer is introduced to refine the focus of the model by assigning different levels of importance to each word in the sequence. This mechanism first computes attention scores based on contextual representations and then applies gating weights to regulate focus intensity. By dynamically modulating these weights, the model can suppress irrelevant information while emphasizing crucial words that contribute to relationship detection.

The final gated attention weights are computed using the following equation:

where

represents the weight of the bias that determines the degree of focus on each hidden state and

is the calculated attention score. By integrating these components, the model improves its ability to capture key relationship indicators, leading to a more precise and robust entity-relationship extraction.

Ultimately, the context vector is calculated using Equation (8), which creates a global representation of the input sequence by combining the weighted representations of every word.

where n is the length of the input sequence.

The multi-head attention layer’s subsequent input layer receives the context vector from the gated attention layer. Here, the inputs are linearly processed using Equations (9)–(11) to produce the query, key, and value matrices, Q, K, and V.

where

,

, and

are trainable weight matrices that project the input vectors to different subspaces.

The weights of the attention allocation were then calculated by Equations (12) and (13):

where

denotes the dimension of the matrix K;

indicates the output of the ith attention head;

,

, and

represents the weight matrix of the ith attention head.

In the end, Equation (14) splices the outputs of each header together, and linear transformation yields the final output:

where Concat is the linear transformation’s weight matrix and

means to join the outputs of each attention head.

The outputs of Equations (6) and (14) are fed into the second BiLSTM layer to extract the local information, and then the results are fed into the main body extraction part via Equation (15):

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication, and A is the attention-enhanced feature map produced by the multi-head and gated attention modules.

The CRF layer uses the high-quality feature representations produced by the aforementioned modules to globally optimize these features, guaranteeing the accuracy and consistency of the output sequences via equations. The Equations (16)–(19):

where

is the sum of the scores for the input sequence (x) and the label sequence (y); n is the length (i.e., word count) of the input sequence.

indicates the element of the label transfer matrix, which represents the label transfer score;

indicates the vector of observed feature weights, which represents the observed feature weights of the label

’ and indicates the output feature representation of the Attention-Enhanced BiLSTM module, which represents the label

’s observed feature weights; and indicates the Attention-Enhanced BiLSTM module’s output feature representation, which represents the feature vector’s ith word.

where

denotes the normalization factor, which represents the total score of all possible label sequences; Y indicates the set of all possible label sequences; exp is the exponential function, which is used to transform the results of the scoring function into positive values.

where

denotes the conditional probability of the labeled sequence y given the input sequence X. The CRF layer is employed solely to enhance sequence-level feature coherence and does not constitute an independent decoding stream for subjects or objects. All relational triples are decoded exclusively through the CasRel-based span prediction mechanism described in

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5.

The final loss function is obtained as follows:

3.3. Dynamic Adaptive Framework

In this section, we present the proposed dynamic adaptive framework, which introduces sample-dependent module activation into the joint entity–relation extraction model. The goal of this design is not to alter the overall CasRel-style decoding paradigm, but to adaptively allocate modeling capacity according to the complexity of each input sentence, thereby improving robustness and representation adequacy.

Sentences in real-world information extraction datasets exhibit significant heterogeneity in length, syntactic structure, and relational complexity. Applying an identical sequence of feature modeling modules to all sentences may lead to underfitting for complex cases or unnecessary computation for simple cases. To address this issue, we introduce a dynamic adaptive mechanism that selectively activates a subset of feature modeling modules for each input sample. However, several intermediate modules are optionally executed based on learned activation scores. This design preserves a stable decoding structure while enabling flexible representation learning.

The proposed dynamic adaptive framework operates at the module level and the sample level. For each input sentence, the model predicts a set of scalar activation scores that control whether the following modules are executed:

The second BiLSTM layer and the CRF decoding layer are always active and are not subject to dynamic gating. The activation mechanism does not operate at the token level or attention-head level; instead, each activation score corresponds to an entire module and is shared across all tokens within a sentence.

Let the encoder output be denoted as , where B is the batch size, S is the sequence length, and d is the hidden dimension. To obtain a sentence-level representation, the encoder output is flattened along the sequence and feature dimensions: .

A lightweight selector network is applied to predict activation scores:

where

,

,

is the number of gated modules, and

. Each scalar

represents the activation score of module

i for a given input sample.

Let

denote the encoder output. For each gated module

i, the intermediate representation is updated according to

where

denotes the transformation implemented by the corresponding module. In practice, a module is considered active if the average activation score over the mini-batch exceeds a predefined threshold, which is set to

in our implementation.

This conditional execution mechanism enables the model to bypass certain feature modeling modules for simpler inputs while retaining them for more complex sentences.

Gradients from the extraction loss propagate through the activation scores via standard backpropagation. No explicit sparsity or efficiency-oriented regularization is imposed; instead, the sigmoid-based activation naturally encourages selective module utilization.

The primary objective of the dynamic adaptive framework is to enhance robustness and adaptive utilization of model capacity rather than to guarantee explicit inference speedup. Potential computational savings are reflected indirectly through reduced module activation and may be further realized with optimized conditional execution implementations. We provide a concrete toy example in

Appendix A to illustrate the complete decoding process, including the encoder output, the predicted subject span, the relation-conditioned object span, and the final triple construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z.; Methodology, X.J.; Software, B.Z.; Validation, X.H. and B.Z.; Formal analysis, B.Z.; Investigation, X.H.; Resources, X.J.; Data curation, X.J.; Writing—original draft, B.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.J. and X.H.; Supervision, X.J.; Project administration, X.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to data privacy protection and restrictions on usage rights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zengeya, T.; Fonou-Dombeu, J.V. A review of state of the art deep learning models for ontology construction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 82354–82383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.U.; Qureshi, R.; Shah, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M.B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J.; Mirjalili, S. Large language models: A comprehensive survey of its applications, challenges, limitations, and future prospects. Authorea Prepr. 2023, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Khemani, B.; Patil, S.; Kotecha, K.; Tanwar, S. A review of graph neural networks: Concepts, architectures, techniques, challenges, datasets, applications, and future directions. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Chang, Y. A Novel Cascade Binary Tagging Framework for Relational Triple Extraction. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1476–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, M.; Yang, W. Review of entity relation extraction. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 44, 7391–7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, M.; Ji, D.; Zhu, Q. Tree kernel-based relation extraction with context-sensitive structured parse tree information. In Proceedings of the 2007 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning (EMNLP-CoNLL), Prague, Czech Republic, 28–30 June 2007; pp. 728–736. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Liu, K.; Lai, S.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, J. Relation classification via convolutional deep neural network. In Proceedings of the COLING 2014, the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers, Dublin, Ireland, 23–29 August 2014; pp. 2335–2344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, D.; Hu, X.; Yang, M. Bidirectional long short-term memory networks for relation classification. In Proceedings of the 29th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation, Shanghai, China, 30 October–1 November 2015; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Shi, W.; Tian, J.; Qi, Z.; Li, B.; Hao, H.; Xu, B. Attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory networks for relation classification. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, H. CNN-BiLSTM-Attention: A multi-label neural classifier for short texts with a small set of labels. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, T.; Majumder, N.; Goyal, P.; Poria, S. Deep neural approaches to relation triplets extraction: A comprehensive survey. Cogn. Comput. 2021, 13, 1215–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Che, W.; Liu, T.; Qin, B.; Yang, Z. Pre-training with whole word masking for chinese bert. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 3504–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, S.; Sanyal, S.; Nitin, V.; Talukdar, P. Composition-based multi-relational graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.03082. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Huang, C.; Swami, A.; Chawla, N.V. Heterogeneous graph neural network. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zitnik, M.; Shang, J.; Langlotz, C.; Han, J. Cross-type Biomedical Named Entity Recognition with Deep Multi-Task Learning. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miwa, M.; Bansal, M. End-to-end relation extraction using lstms on sequences and tree structures. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1601.00770. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, N.A.; Sarker, Y.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Ryan, M.J.; Ahamed, M.H.; Saha, D.K.; Badal, F.R.; Das, S.K.; Ali, M.F.; Moyeen, S.I.; et al. Graph neural network: A comprehensive review on non-euclidean space. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60588–60606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chen, K.; Zhao, T. Document-level relation extraction with reconstruction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 14167–14175. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wei, L.; Wang, Z. A Review and Outlook of the Latest Results on Document-level Information Extraction. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 96, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, K.; Huang, K.; Xu, T.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Document-level relation extraction with two-stage dynamic graph attention networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 267, 110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A. Adaptive Computation Time for Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.08983. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, F.; Dou, Z.Y.; Darrell, T.; Gonzalez, J.E. SkipNet: Learning Dynamic Routing in Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Luo, X.; Dong, C.; Yang, D.; Luan, B.; He, Z. TDEER: An efficient translating decoding schema for joint extraction of entities and relations. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 8055–8064. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, S. Named entity recognition method of Chinese EMR based on BERT-BiLSTM-CRF. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1848, 012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.J.; Li, P.H.; Ma, W.Y. Graphrel: Modeling text as relational graphs for joint entity and relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 1409–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Che, W.; Liu, T.; Qin, B.; Wang, S.; Hu, G. Revisiting Pre-Trained Models for Chinese Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online, 16–20 November 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Tian, X.; Zhu, D.; Tian, H.; Wu, H. ERNIE: Enhanced Representation through Knowledge Integration. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |