1. Introduction

Today, most of the ships use diesel engines for propulsion and for powering the ship’s systems and the equipment. Normal and efficient operation of both the main and auxiliary diesel engines is essential for the safe voyage and fuel economy. The shipping industry uses highly polluting fossil fuels, and their emissions are responsible for approximately ~2.89% of global greenhouse gas emissions, roughly equivalent to 1 billion tons, per annum, according to the IMO [

1]. The engines with faults consume higher fuel and are consequently responsible for more greenhouse emissions. A report by the Swedish Club (Sveriges Angfartygs Assurans Forening) on the main engine damage estimates that main engine claims account for 28% of total machinery claims and 34% of the costs, with an average claim per vessel of USD 650,000 [

2]. Moreover, the recent environmental legislation catapulted the necessity for rapid development and deployment of smart diagnosis tools across various industries to reduce the carbon footprint and march towards sustainability. Therefore, it is imperative to monitor the condition of engines for energy efficient shipping and predict the impending failures to avoid catastrophic break down.

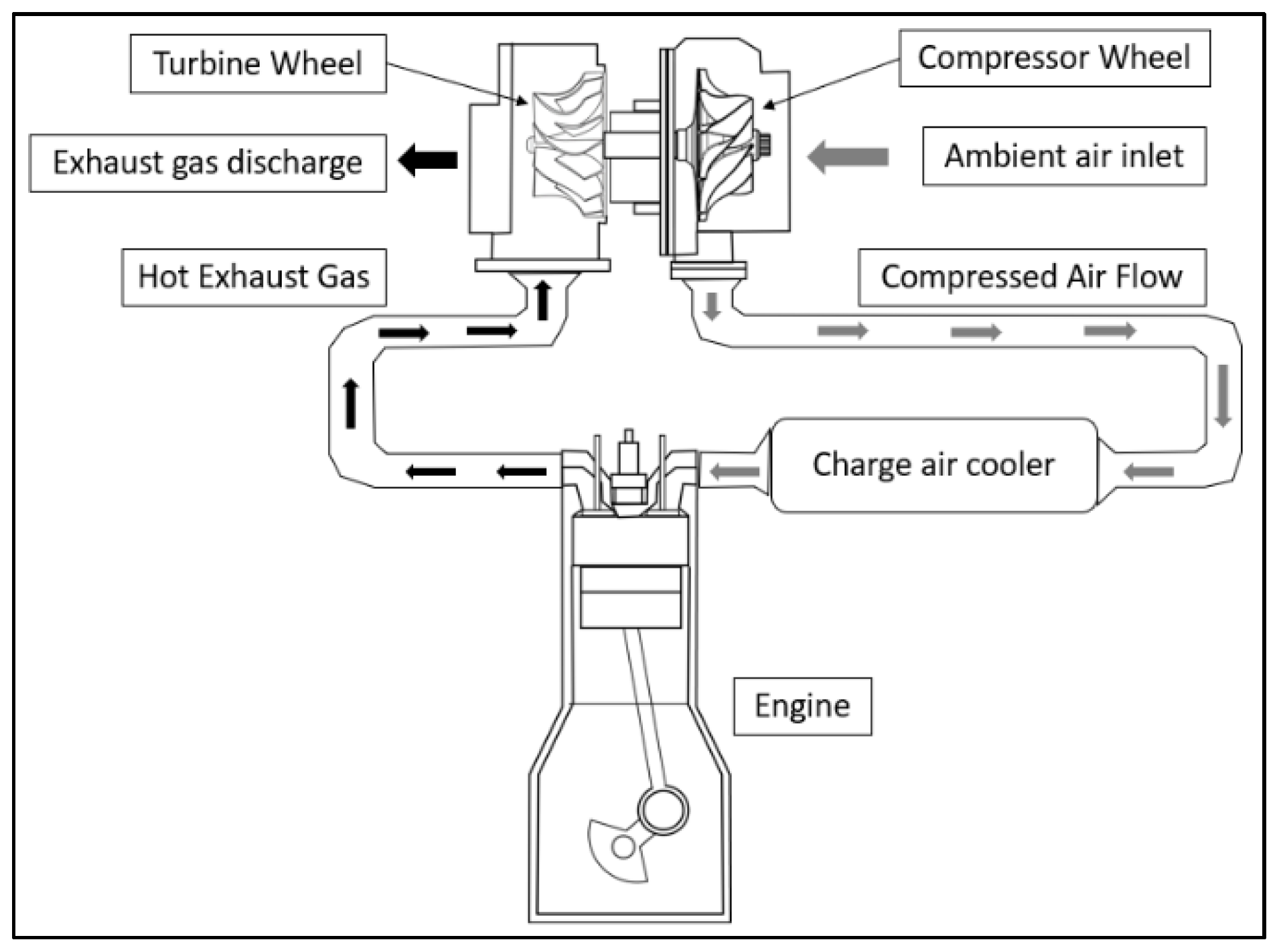

The schematic of a typical marine diesel engine is shown in

Figure 1. A typical auxiliary diesel engine system powering ships’ systems and equipment comprises an internal combustion engine, turbocharger, charged air cooler, and other auxiliary systems for cooling and lubrication. The engine combusts the air and generates power. The exhaust gases are routed to the turbocharger where the expansion of the gases is used for rotating the turbine. The compressor attached to the turbine shaft compresses the air and supplies the charged air to the engine manifold for higher power generation. Malfunction of any of the engine components lowers the power generation capacity and, therefore, it is critical to monitor the condition of engines and subcomponents. Normally, the engine and subcomponents undergo scheduled maintenance after a specific number of operational hours prescribed by the manufacturer. Although, the scheduled maintenance provides longer operational life of engine, it normally results in over maintenance. A key challenge for the unscheduled maintenance of the engine and subsystems is the short window period available for inspection and repair at the port during cargo loading and unloading, and the unavailability of spare parts for the replacement. Therefore, a real-time monitoring anomaly detection and intelligent fault diagnosis tool is essential for predicting the impending failures and for better planning of the maintenance and procurement.

In the marine sector, vibration monitoring and oil analysis are widely used methods for fault diagnosis of diesel engines. Over the years, various vibration-based condition monitoring systems with different signal processing techniques were proposed for fault detection in diesel engines [

3,

4,

5] and are suitable for identifying mechanical faults such as valve failure, unbalance, and bearing or gear failure in the diesel engines. However, the vibration signal is not useful for identifying faults associated with components having non-moving parts such as the air filter, intercooler, inlet, and exhaust manifold. Moreover, most of the works use a single vibration sensor to monitor the faults. However, it is necessary to measure the vibration at several locations and from multiple directions depending on the size of the machines and the fault location and employ data fusion techniques for accurate fault diagnosis [

6].

Fault diagnosis approaches using thermodynamic data were proposed for identifying typical thermodynamic failures such as air filter clogging, intercooler clogging, engine misfire, valve failures, turbine and compressor fouling /clogging, leakages in inlet and exhaust manifolds, etc., in the diesel engines. Lamaris and Hontalas (2010) proposed a general-purpose diagnostic technique for marine diesel engines using a thermodynamic simulation model [

7]. Rubio et al. (2018) developed an engine model using AVL Boost tool to obtain the response of diesel engines for typical failures without having to induce them in a real engine [

8]. The simulator was able to generate symptoms of diesel engines for 15 failures, and the authors also proposed methodology to build a simulator for any diesel engine. Xu Nan et al. (2022) also carried out a similar study and developed an engine simulation model to replicate the influence of various faults on the performance of a marine diesel engine [

9]. Cui, Xinjie et al. (2018) introduced a gas path diagnosis approach for the condition monitoring of a diesel engine turbocharger [

10]. He, Zhichen et al. (2021) proposed a thermodynamic parameter-based performance indicator for the fault detection scheme in marine diesel turbocharging systems [

11]. Xu, Xiaojian et al. (2021) published a more comprehensive review on the various fault diagnosis approaches in the marine systems, their limitations, and the research directions [

12].

Various machine learning (ML)- and artificial intelligence (AI)-based condition monitoring and fault diagnosis tools were proposed in the literature for the marine diesel engines. Li, Zhixiong et al. (2012) presented a feasibility study for fault diagnosis of diesel engines using instantaneous angular speed. Authors used Support Vector Machines (SVM) for multi-class recognition of the marine diesel engine faults and achieved 94% accuracy in fault diagnosis [

13]. Vibration signal was used for fault diagnosis of diesel engines by Porteiro, Jacobo et al. (2011) using Neural Networks [

14] and by Gkerekos et al. (2016) using supervised learning [

15]. Zabihi-Hesari, Alireza et al. (2019) used time and frequency domain features of the vibration signal from intake manifold and cylinder heads of diesel engine as input features to the neural network and achieved classification accuracy of 98.34% [

16]. A hybrid fault diagnosis approach combining manifold learning and isolation forest was proposed by Wang, Ruihan et al. (2021) for accurate fault diagnosis of diesel engines [

17]. Bai, Huajun et al. (2022) employed Stacked Sparse Autoencoder for dimensionality reduction in multi-sensor vibration data and used SVM for fault classification and achieved accuracy of 98% [

18]. A more detailed review of the various ML and AI approaches for fault classification of diesel engines can be found in the literature [

19].

Many works in the literature used the vibration signal for the fault diagnosis of diesel engines. Vibration signal is useful only for fault diagnosis of certain mechanical faults such as unbalance, valve malfunction, bearing faults, etc., and is not useful for diagnosis of faults affecting the thermodynamic performance. The accuracy of fault diagnosis is highly dependent on the vibration sensor location relative to the fault and the presence of nearby auxiliary equipment, and their operation influences the fault detection accuracy. Although multiple vibration sensors were used for the engine fault diagnosis [

6], it is highly challenging in the case of fault diagnosis of auxiliary engines to isolate the fault, as multiple engines at different loads operate at the same time.

Thermodynamic data-based fault diagnosis of engines can detect a higher number of failures with better accuracy. However, it is worth noting that most of works in the literature that are based on the thermodynamic data utilize the simulation models to generate the failure data to avoid testing on a real engine. The accuracy of the simulation models is highly dependent on the tuning of various parameters in the models. The accuracy of model estimation varies from one load point to another load point for the same engine [

8], and the effect of the faults on the engine performance could be in the same range as that of error from the simulation model. Furthermore, some works used data from experiments on a sophisticated and highly sensorized diesel engine test bench. However, the data available from the actual engines onboard the vessel is much less due to the limited number of sensors onboard. Only critical operational parameters are measured and displayed in the engine room. For instance, a mass flow sensor can clearly identify abnormal operations of either engine, compressor, or intercooler. However, it is too expensive to deploy a mass flow sensor on each of the engines. Similarly, it is not practical to measure accurately the maximum temperatures in the cylinder or the pulsating exhaust gas turbine inlet pressure. Fault diagnosis methodologies with minimum engine operational data as input need to be developed for practical implementation. Finally, fault simulation is carried out by varying the process parameters in the models [

8,

9,

10]. For instance, the compressor failure is simulated by reducing the mass flow of air and the isentropic efficiency [

9], and the fault diagnosis was carried out by quantifying the variation in other thermodynamic parameters. A real failure simulation on the actual engine instead of a simulation model would capture the effect of failures in a more realistic way, and such failure data is needed for developing the anomaly detection and fault diagnosis tools.

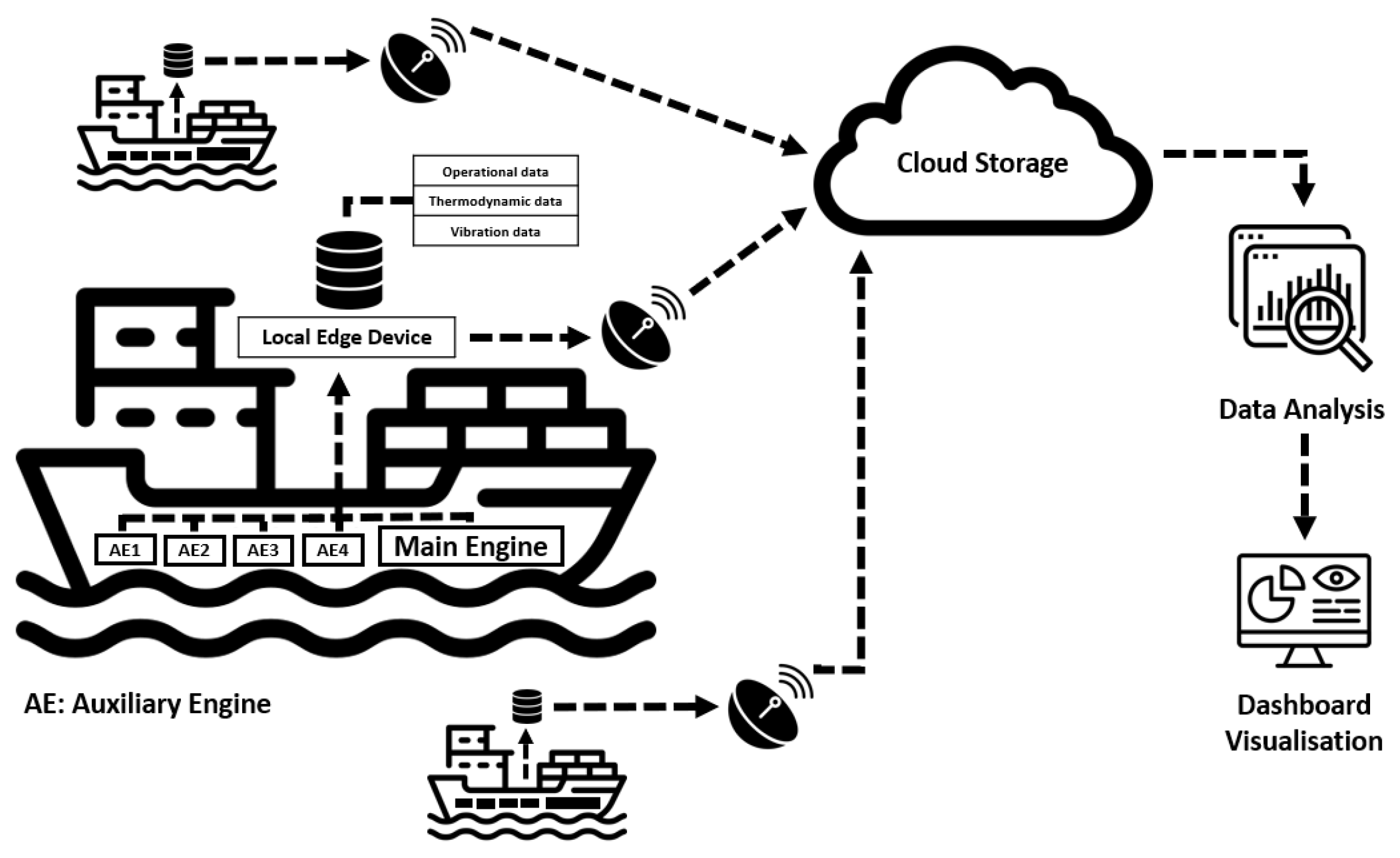

This article aims to present a comprehensive predictive maintenance framework for turbocharger systems, detailing the overall architecture encompassing sensorization of critical components, data acquisition, and edge computation processes, as well as the development of AI-based anomaly prediction and machine learning-driven fault diagnosis models.

This work, firstly, uses the actual operational data acquired from a 1.89 MW auxiliary diesel engine of a cargo vessel for the development of anomaly detection and fault diagnosis models. The healthy data of the engine was collected for two years, and the faults were induced on the actual engine to generate the failure data. As far as the knowledge of the author goes, such work has not been published in the literature. The novelty of the work also lies in using data fusion from both the thermodynamic parameters and vibration for the fault diagnosis instead using either of the data. The presented work acts as guideline for the development of fault diagnosis tools, throws light on the challenges, and showcases the benefit.

Although multi-sensor data have been explored in previous marine engine studies, most existing approaches rely on simulation environments or laboratory test benches with dense and idealized instrumentation. In contrast, real vessels operate under strict sensor, safety, and data-access constraints, resulting in sparse, noisy, and incomplete measurements. The key research gap addressed in this study lies in developing and validating AI-based anomaly detection and fault diagnosis models using multi-modal data collected directly from an in-service marine engine, where fault data are limited and operating conditions are highly variable. This distinction is critical for practical deployment, as models developed under controlled conditions often fail to generalize to real ship environments.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Firstly, the details of the predictive maintenance system of diesel engines, including sensorization and data acquisition, are presented. The details of the marine diesel engine on which the failure simulation is carried out is presented. Subsequently, the approach for inducing the failures with different severity levels on the engine is discussed. Thereafter, the details on the anomaly detection and fault diagnosis models are presented. Finally, the results are presented, discussed, and the conclusions are provided.

3. Anomaly Detection and Fault Diagnosis Models

In this work, two models were developed, one for the anomaly detection and second for the fault diagnosis of the diesel engines. The intention behind developing two models is to serve two different purposes based on the availability of the data. The anomaly detection model is developed to deploy on the marine diesel engines without any previous failure data. The healthy data of the engine will be acquired for a pre-defined interval of time, and the anomaly model will be trained on that healthy data, and the model will be used for prediction of anomalies afterwards. The autoencoder (AE)-based anomaly model predicts the anomaly but will not provide information on the fault type. Therefore, a second model for fault diagnosis is proposed. The fault diagnosis model is developed for the scenario where the failure data is available. With the availability of failure data, the fault diagnosis can also be carried out with better accuracy. Usually, one marine vessel is equipped with multiple auxiliary engines for redundancy. The failure data acquired from one engine can also be used for developing fault diagnosis machine learning models of engines of similar models and with the same rated capacity. It should be noted that the failure data used in this paper is generated by inducing the faults on the diesel engine. The anomaly detection model is to notify the vessel crew or operator on the impending failure, and the fault diagnosis tool provides more specific information on the fault type.

3.1. Anomaly Detection Model

Over the years, many algorithms have been developed to detect anomalies across various applications, and Nassif, Ali Bou et al. (2022) provided a comprehensive review of the literature on the anomaly detection algorithms [

22]. The neural network-based anomaly detection techniques have improved the accuracy of detection on the large and complex datasets, leading to the implementation in wide applications. Supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised anomaly detection algorithms were proposed for anomaly detection in a wide variety of real-world applications.

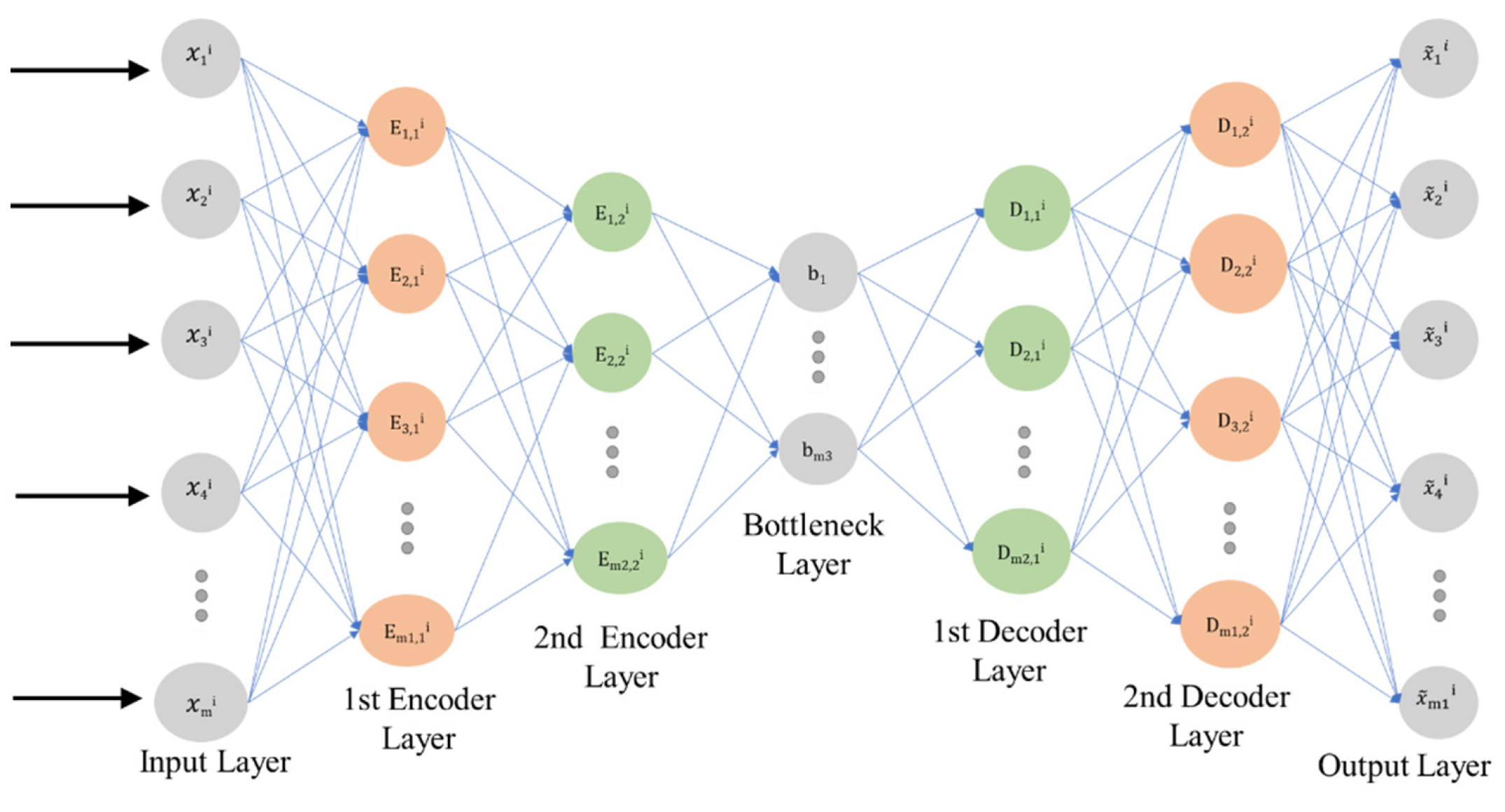

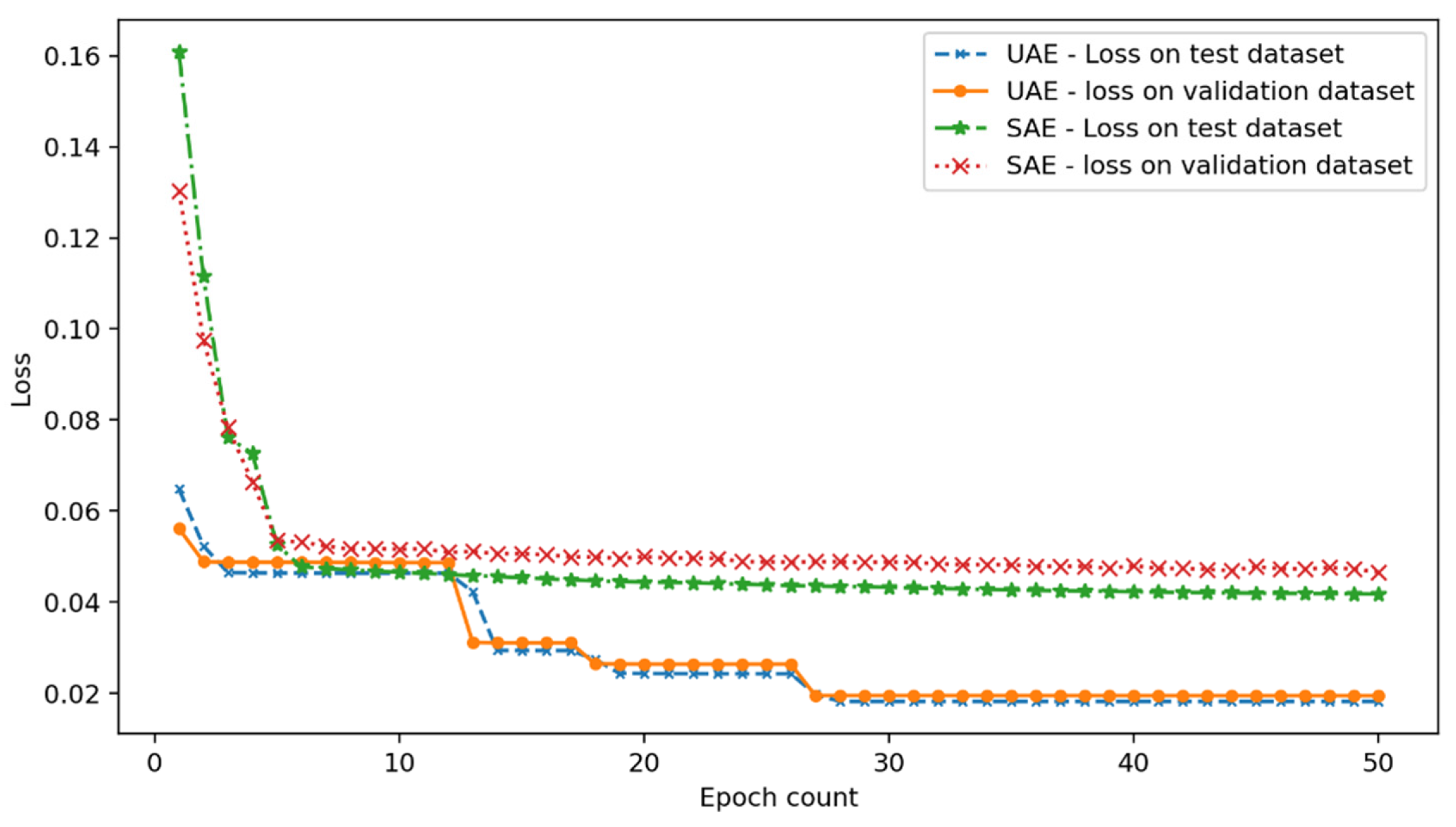

In this paper, unsupervised Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) is used for the detection of the anomalies from the data of auxiliary diesel engine. AE is a neural network-based unsupervised learning algorithm widely applied in data compression and denoising applications. Typically, an AE is composed of an encoder and a decoder, and each of them may contain single or multiple hidden layers. An AE with a single hidden layer is termed as undercomplete autoencoder (UAE), while the AE with many hidden layers is termed Stacked Autoencoder (SAE). AE maps the input data into latent representation at a reduced dimension in the encoding process and reconstructs the data in the decoding process and learns the distribution of the original data. Unlike many of the published works, the SAE in this paper was trained only with healthy engine data without labelling, and the limits of the reconstruction loss on the healthy data was established. The model learns the behaviour of a healthy diesel engine, and the reconstruction loss increases during the prediction when anomalies or some fault beginning to affect the health of engine are present. It should be emphasized that the anomaly detection model detects the anomaly but do not provide any information on the nature of the anomaly.

In this paper, stacked autoencoder is used for anomaly detection in the engine data. The schematic of SAE is shown in

Figure 4. The encoder maps the input sensor data

X = (

x1,

x2,

x3, …,

xN) into a lower-dimensional representation through non-linear transformation along the hidden layers, and the decoder generates an estimation (

) of the input vector

X. The input data

X contains data from m sensors (

,

,

, …

) at each of N observations. The output of each encoder (

Ei) and decoder (

) layer is given by

where

σ is the activation function. The functions

θ and

φ represent the parameter set for the encoder and decoder layers, respectively. Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) was used as the activation function for both encoder and decoder layers. The input data of each layer is transformed to hidden representation through ReLU, and the output representation (

) is computed by minimizing the reconstruction error (

).

The stacked autoencoder (SAE) employed in this study is a deep unsupervised neural network that learns hierarchical feature representations of multivariate turbocharger sensor data. Each autoencoder layer aims to reconstruct its input by minimizing the mean squared reconstruction loss L = , where X is the input vector and is its reconstruction. The encoder transforms the input through a non-linear activation function h = ReLU(Wex + be), while the decoder performs the inverse mapping = W_dh + b_d. By stacking multiple encoding–decoding layers and performing layer-wise pretraining followed by global fine-tuning, the SAE progressively captures higher-order correlations and non-linear dependencies within the turbocharger operating data, allowing it to model complex normal behaviour with high fidelity.

During training, the SAE is exposed only to data representing healthy turbocharger operation. This enables it to learn a compact latent representation of nominal system behaviour, effectively forming a manifold of normal conditions. When new data are passed through the trained model, the reconstruction error E = (1/n) serves as an anomaly score. Higher values indicate a deviation from the learned distribution and thus potential faults. To improve robustness, the ReLU activation constrains hidden features to non-negative values, encouraging sparsity and enhancing interpretability of latent features related to physical parameters such as shaft speed, temperature, and vibration amplitude. This formulation provides a theoretically grounded yet computationally efficient method for anomaly detection, demonstrating improved sensitivity to early degradation patterns compared with traditional linear approaches such as PCA or threshold-based statistical monitoring.

To quantitatively distinguish normal and abnormal operating conditions, the distribution of reconstruction errors from the training (healthy) dataset is modelled using a Gaussian fit E ~ (μ_E, σ_E2). An anomaly threshold T is then defined as T = μ_E + kσ_E, where k is a sensitivity constant empirically chosen between 2 and 3 to control the false-alarm rate. Data samples with E > T are flagged as anomalous. This probabilistic thresholding provides a statistically grounded decision criterion, ensuring that detected anomalies represent statistically significant deviations from the learned normal manifold. In the turbocharger application, this approach allows early detection of abnormal behaviours, such as imbalance or thermal drift, before they manifest as measurable faults.

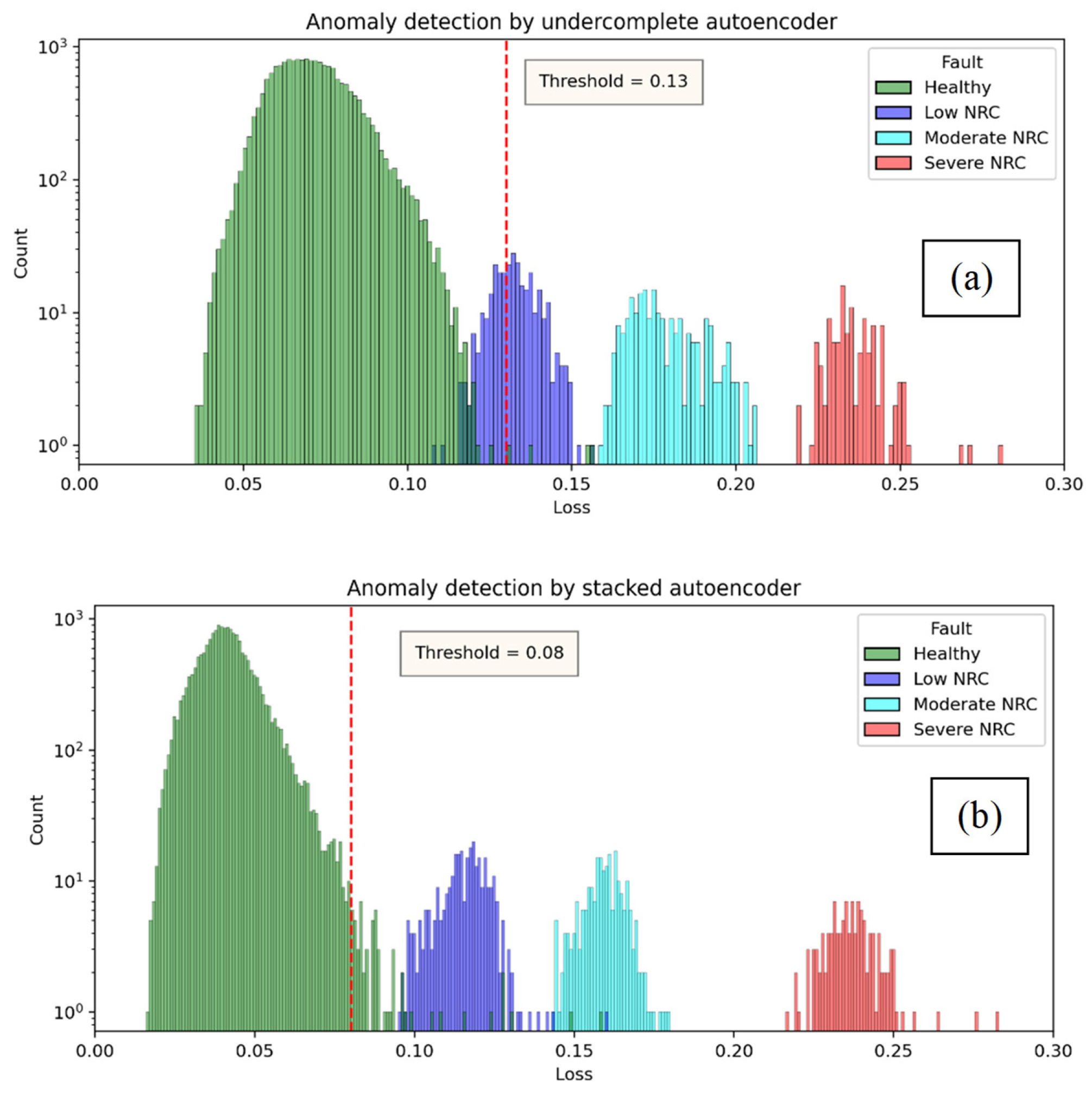

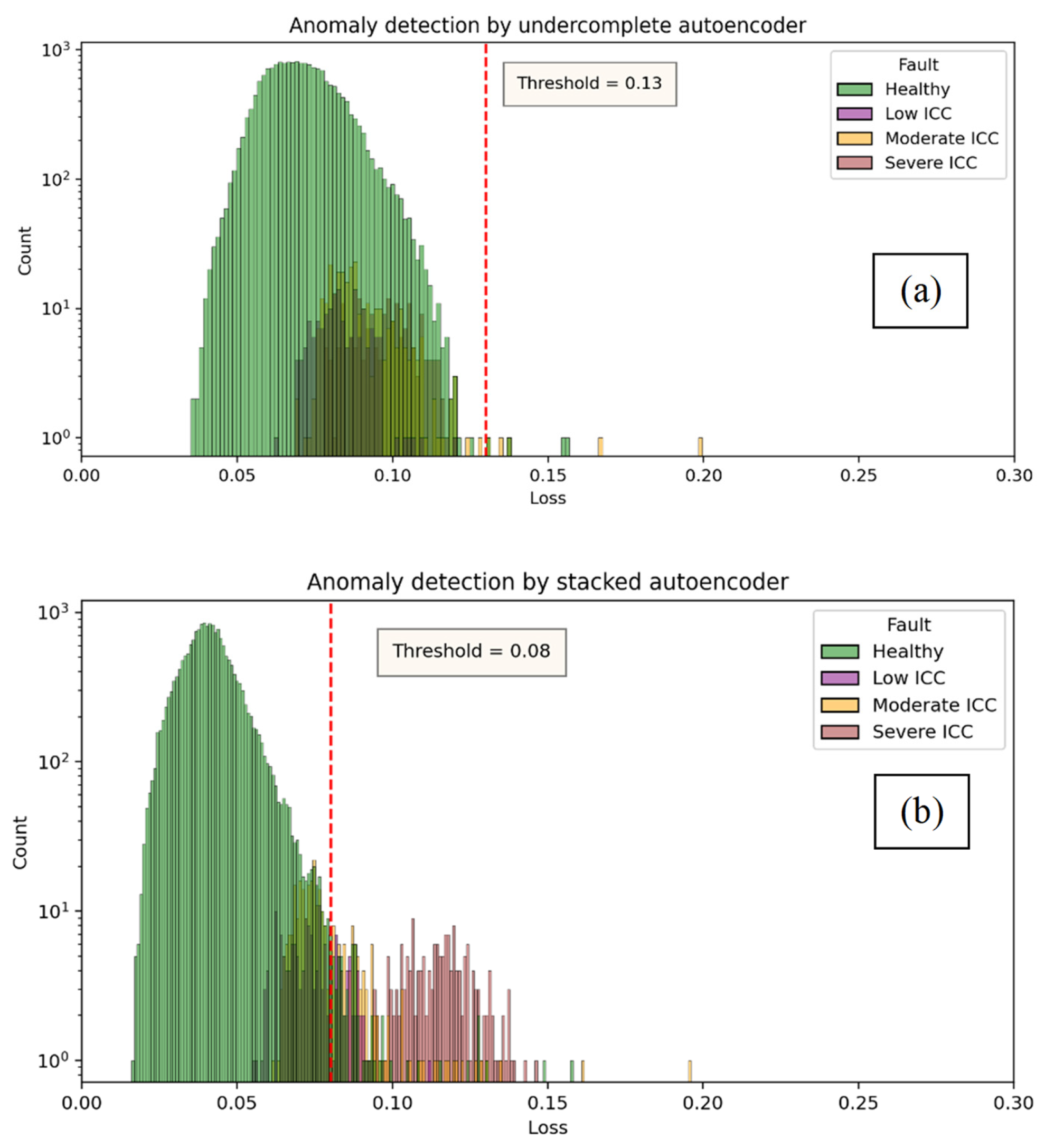

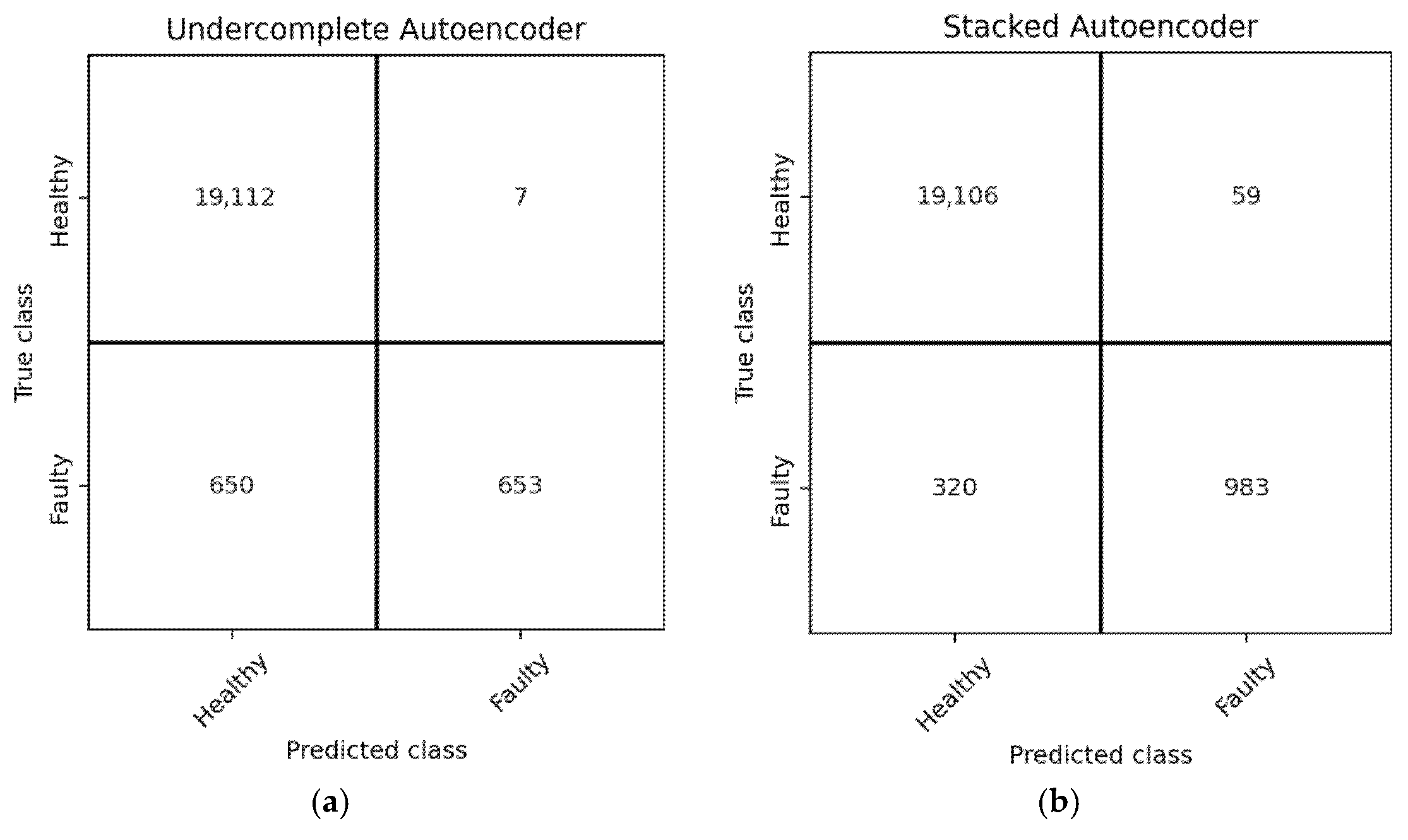

In this paper, the ability of SAE in learning the patterns of the input data is showcased by comparison with UAE. While both the unsupervised autoencoder (UAE) and stacked autoencoder (SAE) aim to learn compact representations of input data without labels, their architectures and learning capacities differ significantly. The UAE typically consists of a single encoder–decoder pair, limiting its ability to capture complex non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data. In contrast, the SAE extends this concept by stacking multiple autoencoder layers, where the output of each encoder serves as the input to the next. This hierarchical structure allows the SAE to progressively learn deeper and more abstract features, making it more effective in modelling the multi-scale dependencies inherent in turbocharger signals. Consequently, the SAE demonstrates superior reconstruction accuracy and anomaly sensitivity compared to a shallow UAE, particularly when dealing with diverse operating conditions and subtle degradation patterns.

The input data of size 96,897 observations with 42 features was reduced to 32, 16, and 8 features successively using three hidden layers to maximize the anomaly detection. The detection accuracy of SAE and UAE is compared to show the capability of SAE in learning complex patters from the data.

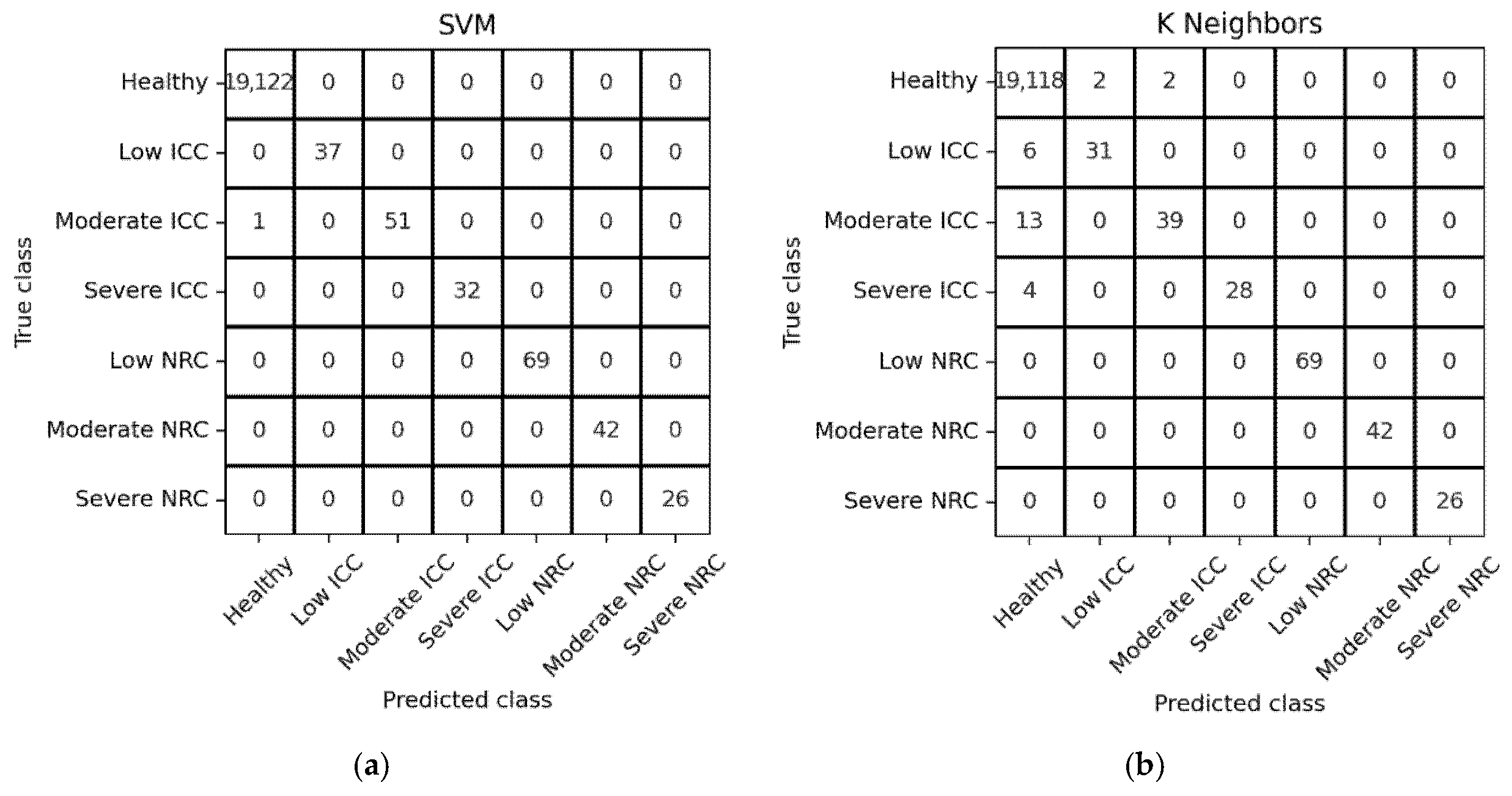

3.2. Fault Diagnosis Model

Numerous ML algorithms have been developed and implemented for fault classification across a wide variety of applications. In this work, various existing models have been trained, tested, and had their accuracy in the fault classification investigated. The top five ML algorithms that have performed well in terms of accuracy in the fault classification are discussed briefly below.

Decision Tree: A Decision Tree is a hierarchical structure that makes decisions by recursively splitting the data based on the feature values. The algorithm selects the best feature to split the data at each node, aiming to maximize the information gain or minimize impurity. This process results in a tree-like structure that can be used for classification by traversing the tree from the root to a leaf node, where the class label is assigned.

Random Forest: Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that combines multiple decision trees to improve the classification performance. It works by constructing multiple Decision Trees using different subsets of the training data and the random feature subsets. The final prediction is made by aggregating the predictions of individual trees, often resulting in more accurate and robust classifications compared to a single Decision Tree.

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XG Boost): XG Boost is a powerful gradient boosting algorithm that focuses on creating a strong ensemble of weak learners, usually Decision Trees. It optimizes a loss function through the iterative addition of trees, with each new tree correcting the errors made by the previous ones. XG Boost uses gradient descent and regularization techniques to prevent overfitting and achieve high predictive accuracy in classification problems.

Support Vector Machine (SVM): SVM is a supervised learning algorithm that seeks to find a hyperplane that separates different classes in the data in the best possible way by maximizing the margin between the classes. It works well for both linearly separable and non-linearly separable data by using kernel functions to transform the data into a higher-dimensional space. SVM aims to classify new instances by their position relative to the decision boundary.

K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN): KNN is a simple instance-based learning algorithm that classifies new data points based on the class labels of their K nearest neighbours in the training dataset. It measures the similarity between the instances using distance metrics (such as Euclidean distance) and assigns the majority class among the neighbours to the new data point. KNN’s effectiveness depends on the choice of K and the relevance of nearby instances.

Although several standard machine learning algorithms were evaluated for fault diagnosis, the contribution of this work lies not in the algorithms themselves but in how they are systematically adapted and integrated for turbocharger fault detection. Specifically, the proposed framework emphasizes (i) feature engineering from real operational signals tailored to mechanical fault patterns, (ii) uniform preprocessing and normalization to ensure fair inter-model comparison, and (iii) an interpretable evaluation pipeline that links model output with physical fault modes. This approach highlights how conventional algorithms can be effectively optimized for domain-specific diagnostics, demonstrating that accurate and explainable fault classification can be achieved even under limited labelled data—a key practical challenge in real-world turbocharger monitoring.

Existing AI- and machine learning-based fault diagnosis studies in the marine domain are predominantly based on simulation data, test-bench experiments, or densely instrumented systems. While these approaches demonstrate promising performance under controlled conditions, their applicability to real vessels is often limited by simplified modelling assumptions, impractical sensor requirements, and the scarcity of labelled fault data. In particular, gradual fouling-related faults exhibit weak and overlapping signatures that are easily masked by operational variability and sensor noise in real-world environments. As a result, the performance and robustness of many existing methods remain uncertain when deployed using the sparse sensor data typically available onboard. This gap motivates the present study, which focuses on evaluating fault diagnosis under realistic operational constraints using real-vessel measurements.

For the above-mentioned ML algorithms, the accuracy, and the balanced accuracy of the classification on test dataset and the cross-validation accuracy are compared, and the results are discussed.

4. Failure Simulation on Diesel Engines

Two failure modes, namely nozzle ring clogging and intercooler clogging, were induced in one of the auxiliary diesel engines onboard the vessel. The focus on nozzle ring blockage and intercooler blockage is motivated by their practical relevance and diagnostic difficulty in real marine operations. Based on technical discussions with industry practitioners, these two fault modes are among the most commonly encountered degradation mechanisms in service and can be safely induced under controlled operating conditions in in-service vessels. Importantly, these were the only fault scenarios approved by the ship’s Chief Engineer for experimentation, ensuring compliance with safety, operational, and regulatory constraints during onboard data collection. While large-scale statistical fault databases from operating vessels are rarely publicly available, particularly for commercial marine engines, fouling-related degradation in turbocharging and charge-air systems is widely recognized as a persistent operational issue. Both faults develop gradually due to fouling and contamination, leading to subtle performance deterioration rather than abrupt failures. This progressive behaviour makes early diagnosis particularly challenging when relying on limited and noisy onboard measurements and therefore aligns well with the objective of this study to investigate fault diagnosis using sparse real-vessel sensor data rather than high-fidelity laboratory instrumentation.

The failure simulations were carried out with increasing severity to generate useful failure data, to develop anomaly detection and fault diagnosis models, and to test the performance of the models. The details of the failure simulation are described below.

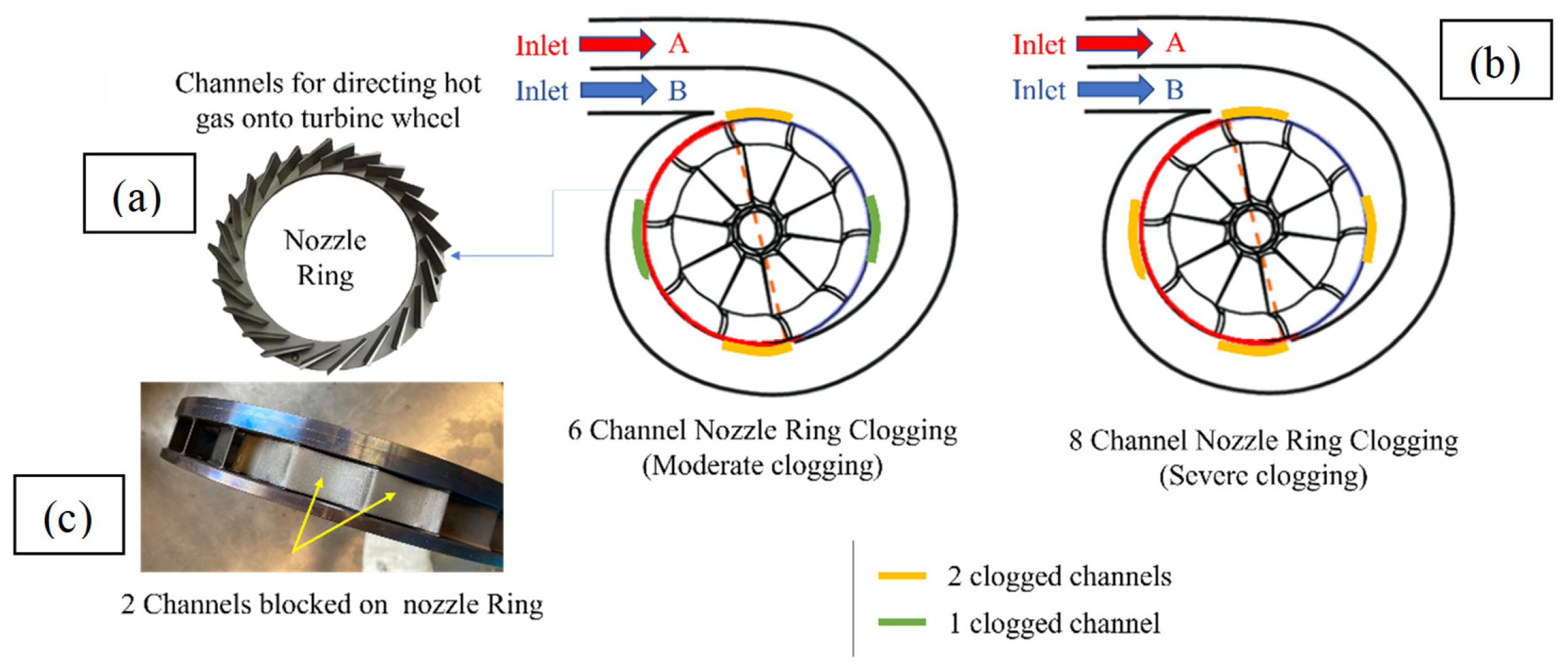

Nozzle ring clogging: Nozzle ring is a critical part of the turbine section of turbocharger, and its function is to direct the hot gas of the engine exhaust onto the turbine blades through its channels. The nozzle ring creates a narrow, high-velocity jet of exhaust gas to strike the turbine wheel at an angle, causing it to spin. Nozzle ring is the most frequently serviced component of the turbocharger because of the depositions formed in its channels. Generally, the marine diesel engines use marine fuel oil or heavy fuel oil for power generation and propulsion. The exhaust of the engine contains soot, and a solid layer of dirt forms on the nozzle ring when hot gas passes through the turbocharger. The pictures of clogged nozzle rings are shown in

Figure 5. Such deposits of dirt in the nozzle ring lead to reduced mass flow in the diesel engine system and hot gas pressure build-up before the nozzle ring. Nozzle ring clogging not only decreases the efficiency of the turbine but also lowers power output of the engine and increases the fuel consumption.

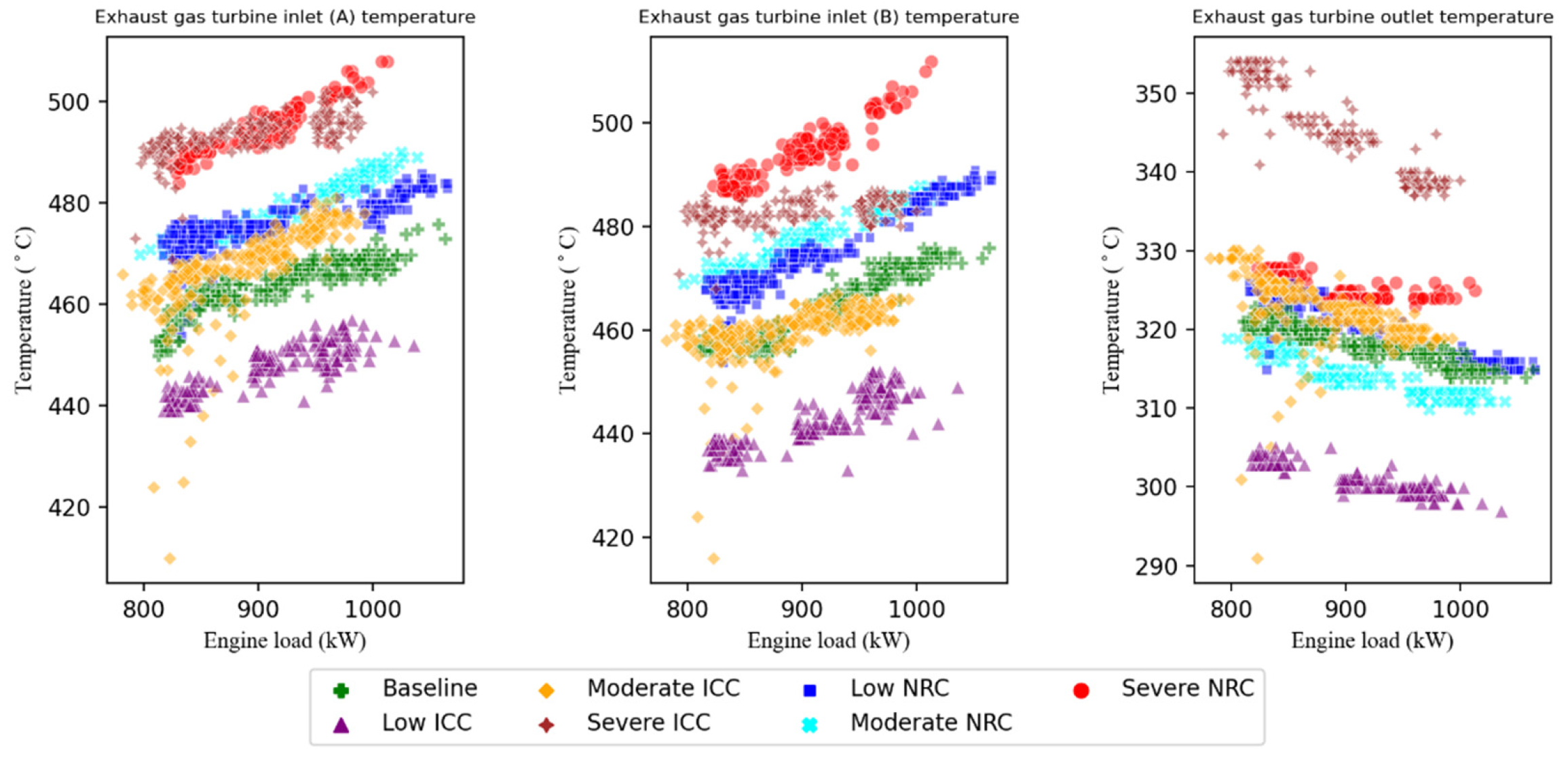

The turbocharger of the diesel engine comprises a twin-entry radial turbine which has two entries, one at the top (entry A) and a second at the bottom (entry B) to direct the hot gas from the engine exhaust on to the turbine as shown in

Figure 6a. Usually, the clogging is more severe at the entrance of hot gas into the nozzle ring. The nozzle ring has 24 channels, and the clogging in the nozzle ring is simulated by blocking the channels. During the nozzle ring clogging simulation conducted on the vessel, four, six, and eight channels were blocked as shown in

Figure 6b to simulate increasing severity of the clogging. The channels of the nozzle ring were blocked with metallic sheets as shown in

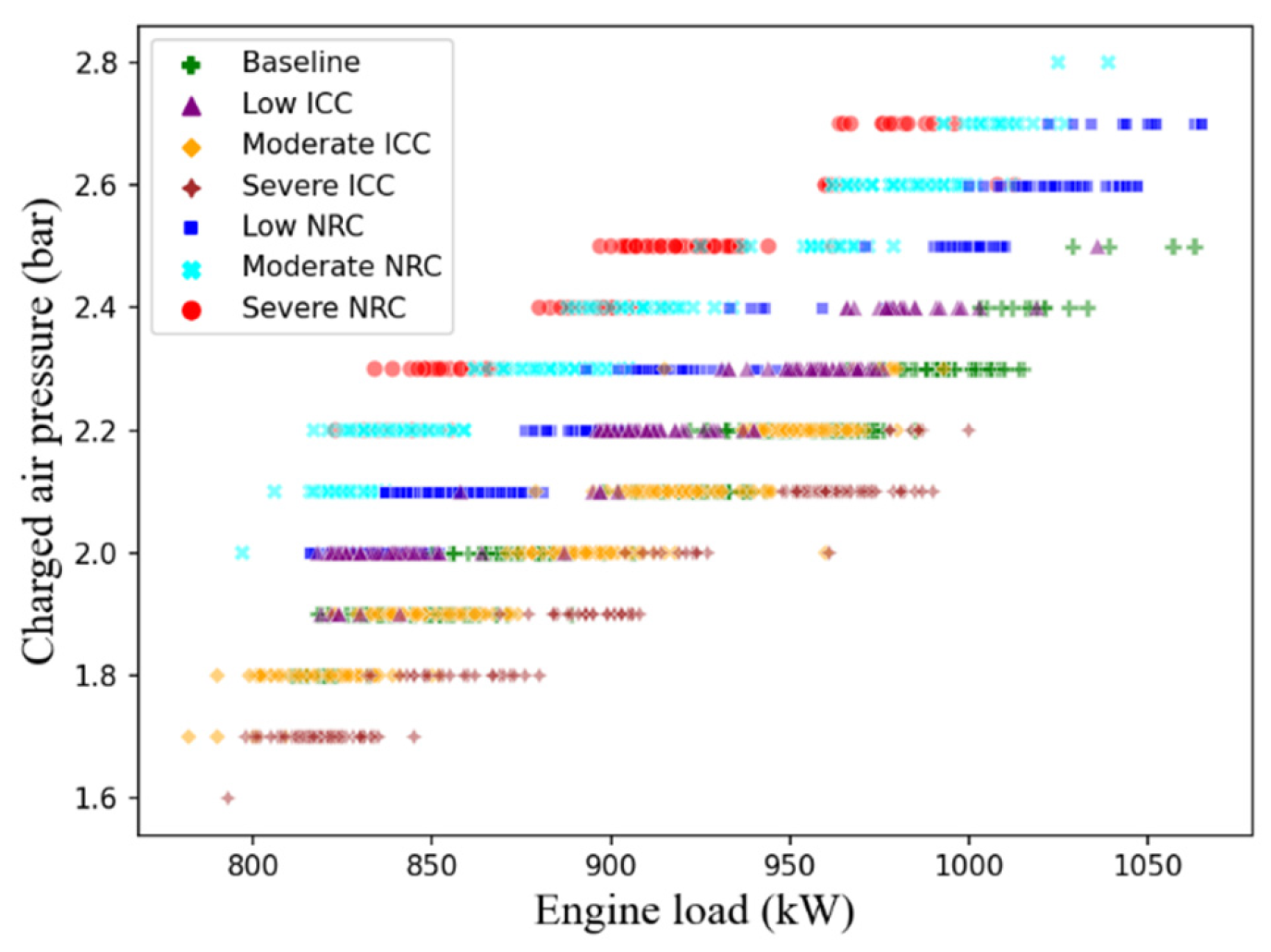

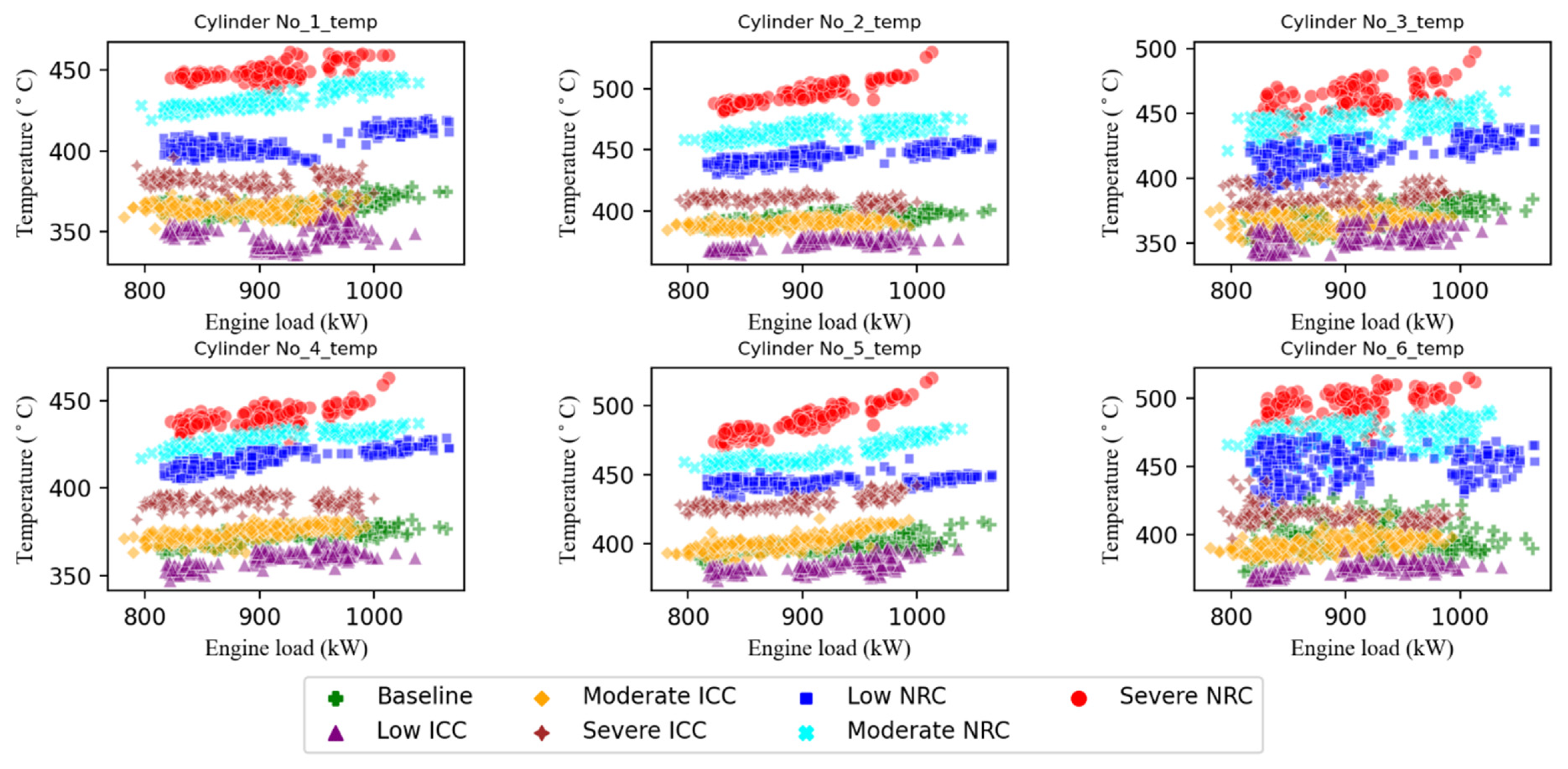

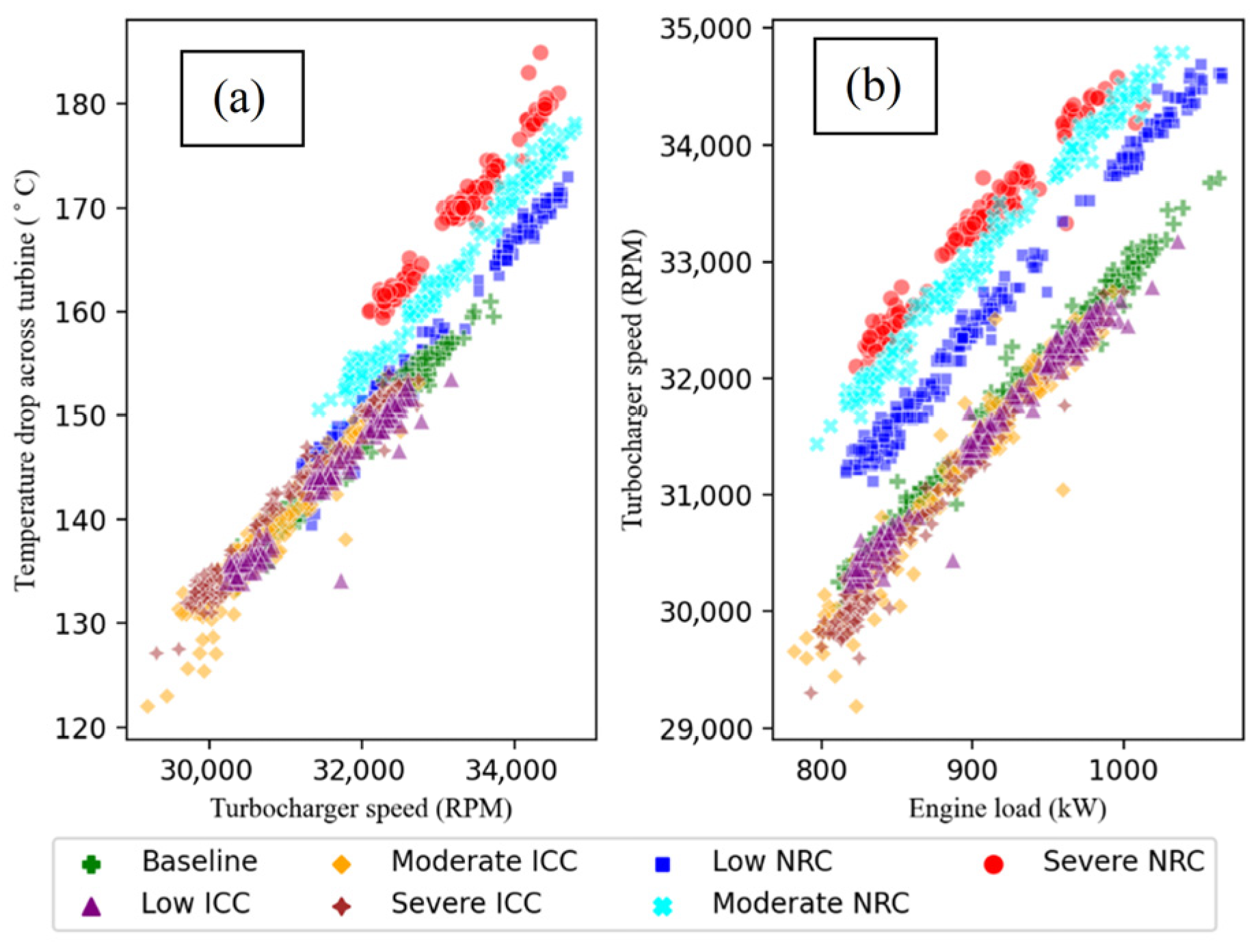

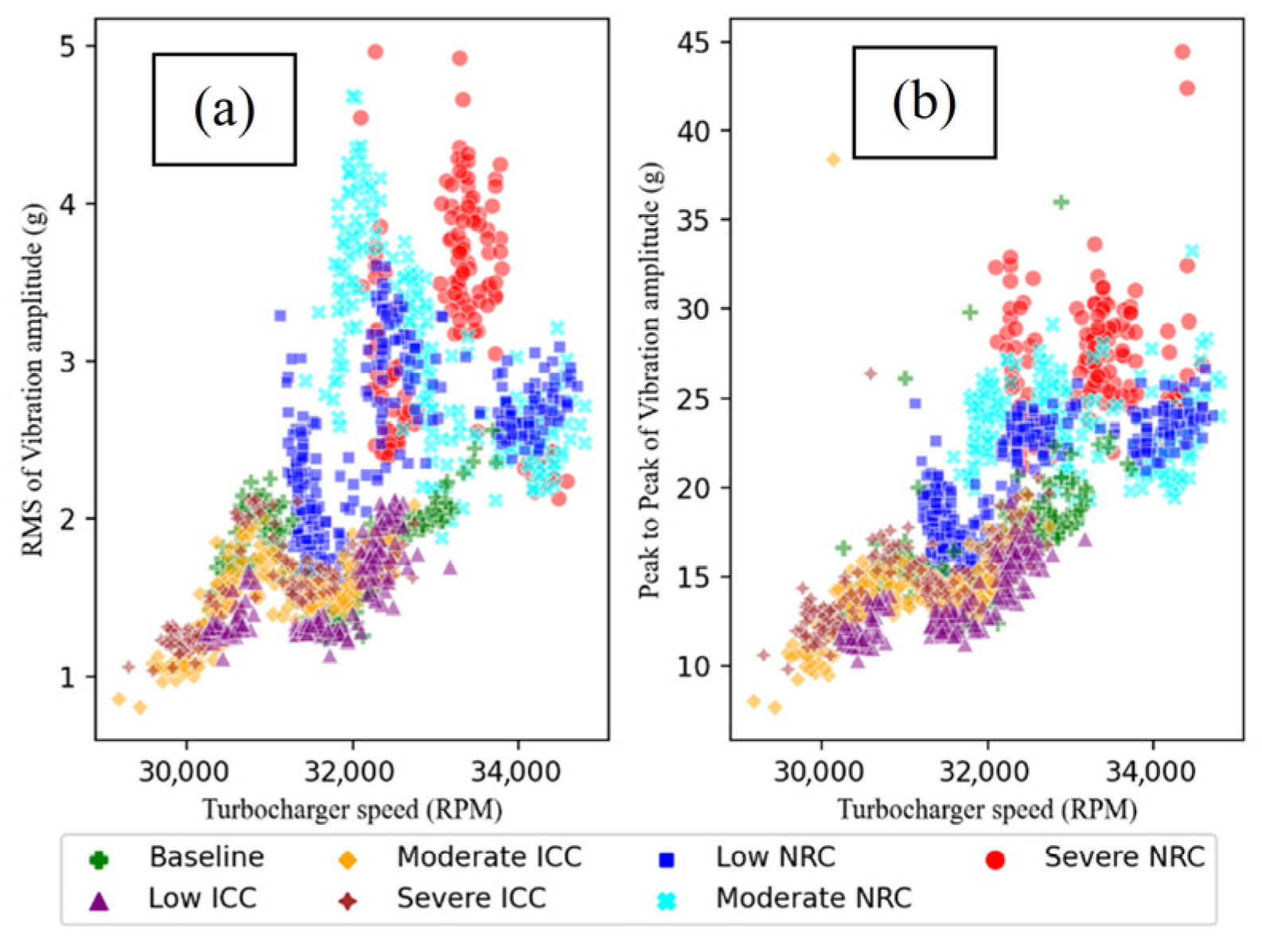

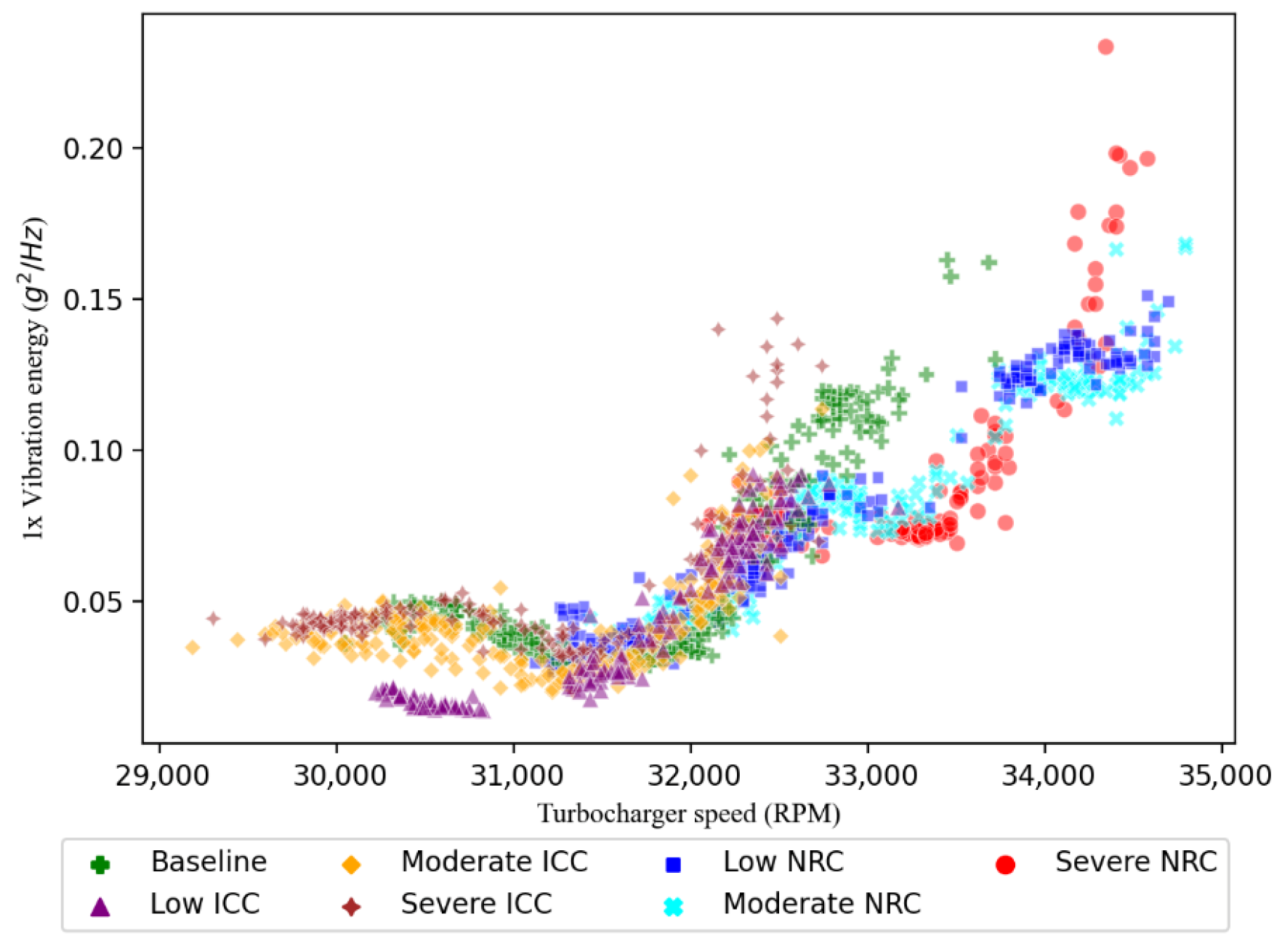

Figure 6c. Three severity levels of nozzle ring clogging were indued during the failure simulation, namely low, moderate, and severe. The severity in the clogging was increased by increasing the number of blocked channels. A total of 4, 6, and 8 channels were blocked during the nozzle ring failure simulation and are termed as low, moderate, and severe nozzle ring clogging based on the percentage of blocked flow area on the nozzle ring. In the subsequent figures and analysis, the labels low NRC, moderate NRC, and severe NRC are used for identifying different levels of nozzle ring clogging.

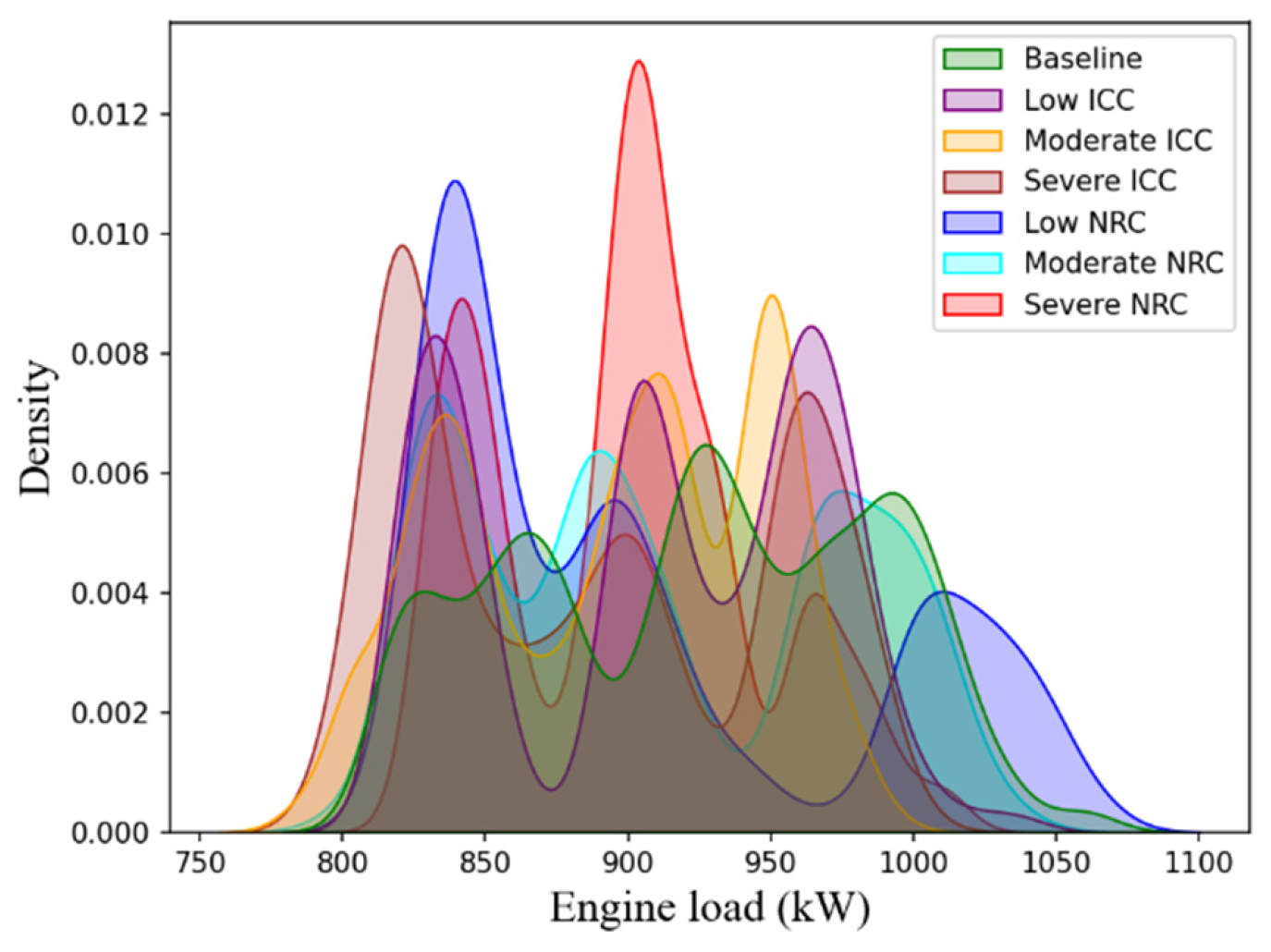

Inter-cooler clogging: During the long operational time of intercooler, the air passages of the intercooler can be clogged or blocked. When the air passages of intercooler are blocked, the pressure builds up on the compressor side and reduces on the engine side. Therefore, the mass flow to the engine reduces. The temperature of the scavenged air entering the engine also increases due to intercooler clogging. Due to the above changes, the performance of engine and turbocharger is adversely affected. In the experiments, the intercooler clogging was simulated by reducing the flow area of the pipe supplying the charged air to the engine manifold by installing an additional gasket with reduced inner diameter. Three severity levels of intercooler clogging were induced in the failure simulation, namely low, moderate, and severe corresponding to 20%, 40%, and 60% blocking of flow area. For instance, to simulate 40% blocking, an additional gasket that covers 40% of the total flow area was installed in the flow path. In the subsequent figures and analysis, the labels low ICC, moderate ICC, and severe ICC are used for identifying different levels of intercooler clogging. The failure simulations of nozzle ring clogging and intercooler clogging were carried out at auxiliary engine loads of 825 kW, 900 kW, and 975 kW using heavy fuel oil.

The simulated faults were designed to replicate partial degradation mechanisms commonly observed in service, rather than destructive or safety-critical failures. In particular, the induced nozzle ring and intercooler blockages represent reversible fouling conditions consistent with early- to mid-stage degradation, ensuring physical relevance while maintaining operational safety. All fault simulations were conducted with approval from the ship’s Chief Engineer and were fully removed after testing, with the turbocharger system restored to its original configuration. Engine operation during the experiments remained within manufacturer-recommended limits, and no long-term impact on engine integrity was observed. The selected load conditions correspond to the most frequently encountered operating points during normal vessel operation, as confirmed through consultation with onboard engineering personnel. These operating points serve as representative sampling locations that capture the dominant engine behaviour relevant to condition monitoring. While dynamic load transients and extended load coverage may provide additional insights, they were intentionally excluded to minimize operational risk and experimental complexity and are identified as directions for future work.