This section assesses the performance of PRA-UNet using both quantitative and qualitative methods. It begins by presenting the training configurations and validation results, including validation on the BraTS 2020 dataset to ensure robustness and generalization. Then, the overall testing results and detailed performance evaluation are discussed. A subsequent comparative analysis highlights the superiority of PRA-UNet over existing state-of-the-art methods. Finally, the deployment prospects and clinical integration potential of PRA-UNet are discussed.

4.1. Training and Test Phase Analysis

This section provides a detailed review of the PRA-UNet setup used to segment 2D brain tumors from MRI data. We created five configurations to systematically evaluate the role of each architectural component and its impact on the performance of the final model. Each configuration omits specific modules from the architecture, allowing their effect on segmentation performance to be measured. The evaluation uses both quantitative results and visual examples to support design choices and clarify performance differences.

Figure 7 shows an example of the four configurations.

The configurations are defined as follows:

Configuration A: This configuration removed inverted residual blocks in the encoding phase. The objective is to examine whether using only bottleneck residual blocks improves segmentation accuracy through enhanced feature extraction.

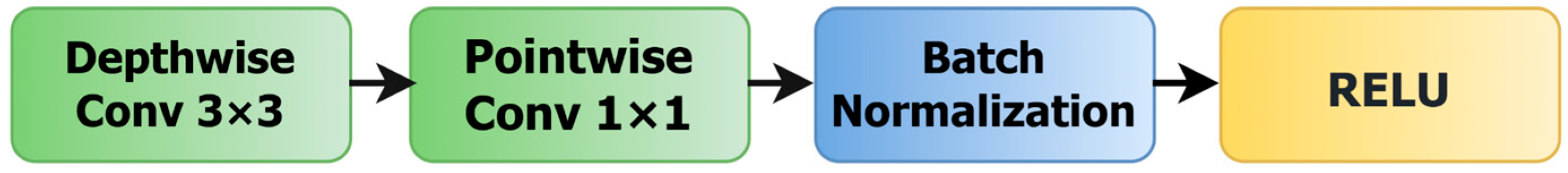

Configuration B: This configuration removed bottleneck residual blocks in the encoding phase. It is designed to assess the effect of depthwise separable convolutions, applied via inverted residual blocks, on model performance.

Configuration C: In this configuration, SAMs are removed from the skip connections. This isolates the effect of spatial attention and allows us to evaluate whether direct encoder–decoder connections suffice for accurate segmentation.

Configuration D: In this configuration, the CBAM is removed from the bridge, and a direct connection is established between the encoder and decoder. This setup tests the impact of removing channel attention in favor of uninterrupted information.

PRA-UNet: This is the original configuration. It integrates both bottleneck and inverted residual blocks, includes SAMs in the skip connections, and retains the CBAM in the bridge. This full-featured setup serves as the reference configuration for comparison.

Table 3 presents the performance evaluation of the models during the training phase, using a 5-fold cross-validation methodology. This analysis highlights the strengths and limitations of each configuration in brain tumor segmentation.

The results clearly demonstrate the superior segmentation performance of PRA-UNet compared to configurations A, B, C, and D. Specifically, PRA-UNet achieves a maximum Dice of 98.15%, coupled with a peak IoU of 96.36% and a remarkable accuracy of 99.83% during the second training iteration. Throughout the training iterations, PRA-UNet maintains high metrics consistently, with Dice ranging from 97.09% to 98.15% and IoU values between 94.34% and 96.36%. These results confirm the robustness and effectiveness of PRA-UNet in accurately segmenting medical images, notably outperforming other comparative architectures.

In contrast, configurations A and B, which exclusively use bottleneck residual blocks or inverted residual blocks, exhibit lower performance, with Dice scores below 95.86%. Configuration C, excluding SAM from skip connections, achieves a modest improvement yet remains inferior compared to configuration D. Configuration D, which lacks the CBAM from its bridge, performs better but does not reach the high Dice and IoU scores achieved by PRA-UNet.

The narrow gap between accuracy and Dice in PRA-UNet indicates a well-calibrated model that distinguishes tumor structures. Accuracy mainly focuses on how many pixels were correctly classified, while Dice is more sensitive to FN, making it a stricter test of missed segmentation areas. The slight difference between the Dice and IoU scores (1.79–2.75%) shows that PRA-UNet is even more accurate. This small gap indicates that the predicted and actual segmentation masks are very similar and have perfect overlap.

PRA-UNet also has much lower loss values during training, between 0.0114 and 0.0179. This shows that it is better at optimizing and converging than other models. This lower loss matches up perfectly with the great DSC and IoU metrics, which show that the model can extract features quickly and segment images accurately. The learning curves in

Figure 8 further substantiate these findings, as they exhibit a stable validation loss without any indication of overfitting. This means that PRA-UNet can reliably generalize new data.

The results in

Table 4, which show the average performance metrics for all training iterations, back up these claims. PRA-UNet has the best overall average performance of all the configurations tested. It has an average Dice of 97.61%, an Accuracy of 99.78%, and an IoU of 95.34%, as well as the lowest average loss of 0.0147.

Table 5 looks at how well the configurations can work with unseen data. It displays the average results from the test phase. PRA-UNet shows that it works well most of the time, with an average Dice of 95.71%, an Accuracy of 99.61%, and an IoU of 91.78%. Even though the training metrics show a small drop, this drop is not significant, which shows that PRA-UNet can effectively generalize real-world data. On the other hand, some configurations show much bigger drops, which shows that they are not as good at generalizing. This difference in performance shows how strong and useful PRA-UNet is in the clinic for accurately separating brain tumors.

Table 6 provides a deeper statistical exploration of the segmentation performance of all configurations by incorporating not only the Avg and σ, but also the SEM and CI95 and CI99. These metrics offer a more rigorous evaluation of result stability and the reliability of performance differences between models.

Overall, PRA-UNet shows the most minor variance, the lowest SEM, and the tightest confidence intervals among all configurations. These results indicate superior consistency across the five test runs, confirming the model’s robustness and its ability to maintain stable predictions even when exposed to variation in test data.

For the Dice, PRA-UNet achieves an average of 95.71 ± 0.14, with an extremely small SEM (0.0626) and very narrow confidence intervals (CI95 = 95.71 ± 0.122, CI99 = 95.71 ± 0.161). These narrow intervals demonstrate that the differences between test folds are minimal and that the actual Dice performance of PRA-UNet almost certainly lies very close to the reported Avg.

In comparison, the other configurations (A–D) exhibit larger σ and wider CI ranges, indicating greater variability across test folds and thus lower statistical reliability. This variability shows that although some configurations achieve acceptable mean performance, they do not consistently maintain this behavior across different test splits.

A similar pattern appears for the IoU metric. PRA-UNet again displays the best stability, with an Avg IoU of 91.78 ± 0.26, an SEM of 0.116, and very compact confidence intervals (CI95 = 91.78 ± 0.227, CI99 = 91.78 ± 0.299). This statistical precision indicates a high level of repeatability in segmentation predictions, an essential requirement for real clinical deployment. Conversely, the IoU values for configurations A and D exhibit wider confidence intervals, indicating less predictable performance and greater sensitivity to data variation.

Taken together, the metrics in

Table 6 confirm that PRA-UNet is not only superior in terms of average performance but also statistically more reliable and stable. Its consistently narrow CI ranges underline its strong generalization capability and reinforce its suitability for medical image segmentation tasks where precision and reliability are crucial.

Beyond quantitative metrics, qualitative assessment remains crucial for evaluating segmentation quality in clinical applications.

Figure 9 presents a visual comparison of segmentation results, demonstrating that PRA-UNet achieves more accurate, refined tumor segmentation than other configurations. However, as shown in sample 5, all configurations, including our proposed approach, struggle with the segmentation of small tumors, highlighting an ongoing challenge in brain tumor segmentation.

Although PRA-UNet exhibits exceptional performance in brain tumor segmentation, its real-time efficiency depends on its computational complexity. To assess its feasibility in a clinical setting, several parameters are considered, including the number of parameters, memory size, inference latency, and FLOPS. Here, we compare PRA-UNet with configurations A, B, C, and D, which were previously evaluated for their segmentation performance.

The results in

Table 7 show that configuration A is the most lightweight, with only 0.33 million parameters, a memory footprint of 4.18 MB, and the lowest latency (54.10 ms). Despite its high efficiency and suitability for real-time applications, its simple architecture ultimately limits its segmentation performance. Configuration B, slightly more complex with 0.70 million parameters and a memory size of 8.36 MB, shows a significant increase in latency (96.44 ms) without delivering a meaningful improvement in segmentation accuracy, reducing its practical relevance compared to PRA-UNet.

Configurations C and D exhibit increased complexity without proportional gains in segmentation quality. Configuration C, with 1.68 million parameters and a memory footprint of 19.65 MB, achieves moderate latency (67.72 ms) but incurs a high computational cost (9.52 GFLOPs), offering only a modest improvement over previous models. Configuration D shows a similar trend with 1.55 million parameters and 18.15 MB in memory, achieving lower latency (56.97 ms) but still maintaining a high computational cost (9.50 GFLOPs), with no notable performance benefit. In contrast, PRA-UNet, with 1.69 million parameters and 19.71 MB of memory, effectively balances complexity and accuracy. It achieves a competitive latency of 60 ms and a computational cost of 9.56 GFLOPs, while ensuring robust precision suitable for critical medical applications such as brain tumor segmentation.

4.5. Comparative Analysis

The primary objective of this section is to compare the performance of the PRA-UNet model to that of other open-source architectures that are often used for medical image segmentation. We chose the U-Net, U-Net++, Attention U-Net, ResU-Net, and U-Net++ with Dense models to ensure that the comparison was fair and objective. These architectures are well known in the literature for their efficiency and reproducibility, ensuring that our comparison is transparent and replicable. We used the BraTS 2020 dataset [

45] as a reference to train and test all of the models in the same experimental setting. To reduce external variations that might affect the results, we kept the same experimental conditions as in our previous study.

The evaluation is based on two main criteria: segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency. The DSC and IoU are standard metrics in medical image segmentation that are used to measure accuracy. Inference latency, model parameter count, and memory size are among the metrics used to assess computational efficiency. To assess the robustness of the models, we tested each model using 500 test images that were not part of the training set. We split the images into 20 groups of 25 images each to enable batch-wise evaluation with uniform memory usage. The final reported results represent the overall average computed across all test images.

Table 12 shows that PRA-UNet is highly efficient and competitive, making it a strong candidate among existing medical image segmentation models. PRA-UNet differs from many other cutting-edge architectures that focus solely on accuracy. It strikes a good balance between segmentation performance and computational cost, which is vital for real-world deployment.

PRA-UNet is the best model in terms of computational usage. It has the lowest latency (60 ms), the fewest parameters (1.69 million), and the smallest memory size (19.71 MB). These features suggest that the model could be usable in systems with limited hardware resources, such as portable devices or diagnostic tools operating on the edge. On the other hand, models like U-Net++ and Attention U-Net need a lot more resources, with more than 8 million parameters and memory sizes of more than 120 MB. UNet++ with Dense has the highest Dice score (96.32%) and IoU (92.91%), but it is also the most computationally intensive model, with 10.6 million parameters, a 150 MB size, and a latency of 235 ms. This makes it less suitable for time-sensitive environments.

PRA-UNet is one of the best models in terms of accuracy, with a Dice score of 95.71% and an IoU of 91.78%. This level of accuracy is kept up without slowing down or expanding the model size, even though it is slightly lower than U-Net++ with Dense. Attention U-Net (93.97% Dice, 88.62% IoU) and ResU-Net (92.00% Dice, 85.18% IoU) also perform well, but they are less precise and less efficient than PRA-UNet. U-Net is lightweight in terms of computation, but it fails to segment effectively (85.8% Dice, 75.13% IoU), making it unsuitable for clinical settings where high accuracy is required.

Finally, U-Net++ (90.46% Dice, 82.58% IoU) is more accurate than the original U-Net, but its higher latency (120 ms) and memory requirements (148 MB) do not offer substantial benefits over PRA-UNet. These observations support the conclusion that PRA-UNet provides a superior balance among accuracy, inference time, and model complexity compared to alternative architectures.

PRA-UNet is the most balanced and ready-to-use model of the ones we evaluated. It is a practical and scalable solution for real-time medical imaging applications because it can keep high segmentation accuracy while lowering latency and resource use.

While

Table 12 emphasizes the balance between accuracy and computational cost,

Table 13 complements this analysis by examining the statistical behavior of the models across the five folds. This additional layer of evaluation reveals how consistently each architecture performs, beyond its average Dice and IoU values.

The reference models, including U-Net, U-Net++, Attention U-Net, and ResU-Net, show confidence intervals that remain relatively wide, indicating noticeable fluctuations from one fold to another. These variations suggest that their segmentation performance, although acceptable on average, is more sensitive to data partitioning effects. Attention U-Net and ResU-Net, for instance, present improved mean scores compared to U-Net, yet their dispersion across folds remains significant, revealing a level of instability that is not visible in the mean figures alone.

Among the architectures, U-Net++ with Dense achieves the highest average accuracy, but its confidence bounds still reflect a measurable degree of variability. This nuance, when combined with its high computational demand reported in

Table 11, reduces its practicality in scenarios where both performance and operational constraints must be considered simultaneously.

In contrast, the confidence intervals of PRA-UNet are notably narrower than those of all other models. This pattern indicates that its predictions are more tightly clustered across folds, reflecting a stable and reproducible behavior. These statistical characteristics reinforce the observations from

Table 12: PRA-UNet not only maintains competitive segmentation accuracy with low computational cost but also exhibits a more reliable performance profile, making it particularly suitable for deployment in real-world environments where consistency is essential.

The confusion matrices in

Figure 10 further support the performance advantages of PRA-UNet. The model records 1,426,130 true positives and 31,214,195 true negatives, while keeping false positives at 71,258 and false negatives at 56,417. This reflects accurate detection with limited misclassification.

Compared to other models, PRA-UNet shows a better balance. U-Net++ with Dense has almost similar FN (56,751) and FP (70,924) but requires far more resources. Attention U-Net, although achieving more TP, produces over 100,000 false negatives and more than 111,000 false positives, which affects its reliability.

U-Net and U-Net++ both show higher error rates, especially in false negatives. U-Net, in particular, reaches 232,232 FN, the highest among all models. These results confirm that PRA-UNet achieves fewer errors in both directions—missing fewer tumors and producing fewer false detections—while remaining efficient. This supports its use in clinical settings where both precision and speed are essential.